THE HOME OF THE SURREALISTS

Lee Miller, Roland Penrose and their circle at Farley Farm

BY ANTONY PENROSE

A SURREALIST IN FRIENDSHIP

If we are to move towards a wider consciousness we need constantly to experiment and to understand the experiments of others. That is why I am a Surrealist. To experiment with reality.

ROLAND PENROSE, NOTES TO HIS SPEECH, ‘WHY I AM A PAINTER’ 1937

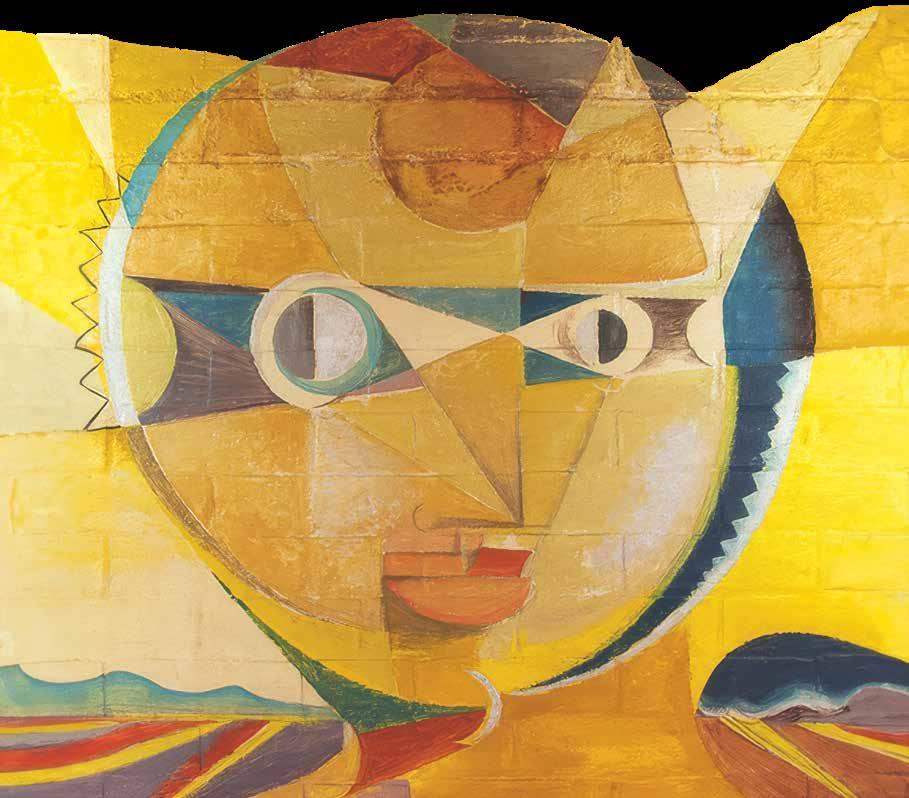

opposite

: Conversation between Rock and Flower, 1928, oil on canvas, by Roland Penrose. above : L-R Roland Penrose, André Breton and Humphrey Jennings at the opening of the International Surealist Exhibition, London, England 1936.

Cambridge and home, but he was too shy to sample the delights offered by the many free-spirited Parisiennes he encountered. His close friend Yanko Varda, a Greek artist, took charge and introduced him to his favourite brothel, where a sympathetic girl made her own successful contribution to his education. From that moment on he adored women, and they him. The eroticism, beauty and mystery of women became the most abiding fascination of his life.

Roland probably first heard about Cassis-sur-Mer from Duncan Grant or Vanessa Bell, as the village was already frequented by members of the Bloomsbury group who enjoyed the delights of Provençal life. In the summer of 1923, he went there with Yanko and impetuously bought Villa Les Mimosas. On the slopes above the town, the small but pleasant house stood discretely behind a high stuccoed wall capped with tiles. Its terrace overlooked a large garden, at the bottom of which Roland and Yanko built a studio. Here Roland began painting in earnest, though at this stage he did not take his work too seriously. Scenes of sea monsters or returning sailors show him playing with the influence of Cubism. He enjoyed the peaceful, carefree life and might easily have

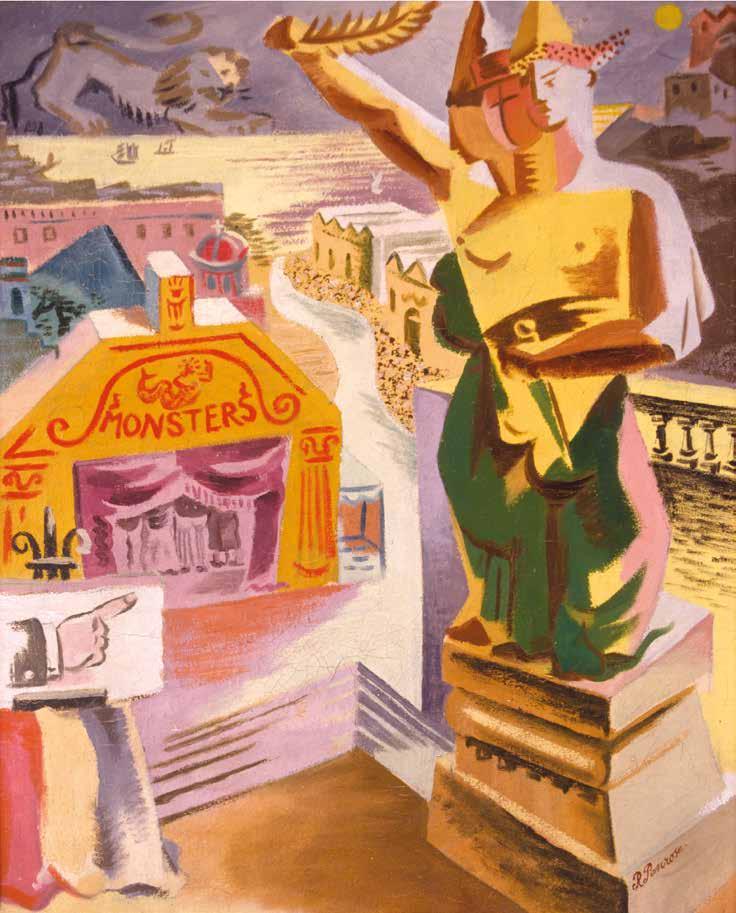

opposite : Monsters,1925, oil on canvas, by Roland Penrose. The influence of Cubism combines with Roland’s growing interest in Surrealism in this painting. The background resembles Cassis-sur-Mer with the Mediterranean beyond. above : Villa Les Mimosas, 1923, Watercolour, by Valentine Penrose. The little tower afforded magnificent views out to sea, over the port and inland up the valley where the castle of La Couronne de Charlemagne looms on the horizon.

below : Road to Cassis, c1924, oil on canvas, by Roland Penrose.

as Éluard encouraged Nusch to sleep with Picasso. At the same time, Roland probably enjoyed a liaison with Ady, and there were many temporary pairings among the others. The exchange of partners among the group was an easy extension of their Surrealist beliefs and their love for each other, made more natural by the relaxed ambience of sunshine and the delights of Provençal food and wine. Forty years later, Roland declared that he and Lee had never been unfaithful to each other – in his view, their many sexual adventures with others did not count as infidelity, since their love remained unaffected. It was a belief that endured, although at times it was stretched close to breaking point.

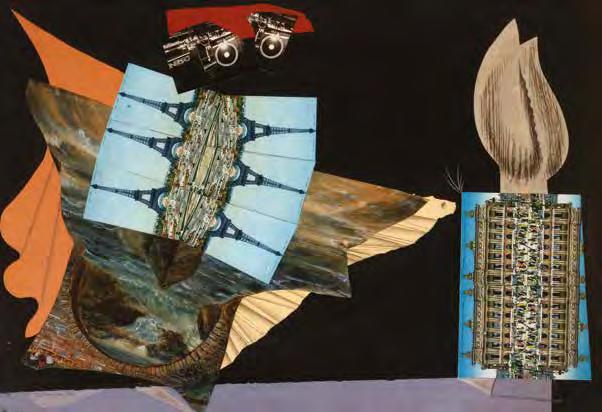

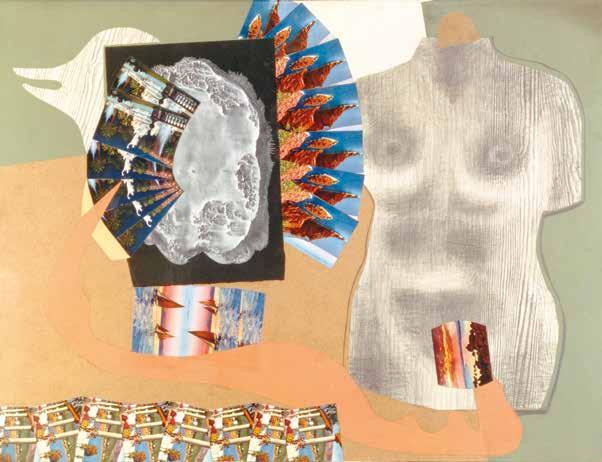

Roland’s creativity was inextricably linked to his romantic life. The ups and downs in his relationship with Valentine can be charted through corresponding changes in his style. But it was Lee, it seems, who during their stay at Mougins, was the catalyst for his invention of the postcard collage. This signature style endured until the end of his life, and remains his original contribution to the art of the period. There is no way of knowing what triggered the idea; perhaps it was the effect of colour patches in the serried ranks of picture postcards on sale in the

local shops. Borrowing from the Cubist’s reduction of form to hard-edged, simplified shapes, Roland began using repetitive swatches of banal picture postcards to provide blocks of colour in his work. The cards were not chosen for their pictures, although the image often adds another layer of meaning to the work. The importance of the cards is their colour and tonality, which, when arranged in a pattern, transcends their original purpose. Other items, like tickets and fragments of printed material, or large areas of gouache or frottage, add to the composition. In later works no holds are barred, and we find bits of string, plant material, metal, and in one piece even a patch cut from an oil painting by one of his aunts. This work, Magnetic Moths (1938), is now in the Tate Modern, which would surely have gratified the old lady.

One of the most important works from this period is a portrait of Lee, titled The Real Woman (1937). On the right, a pencil frottage gives us a sensual picture of her, strongly sexual with the red glow of a sunset signalling the heat of her desire, and recording a direct contrast with Roland’s experience of Valentine’s more ethereal body. Here is a real woman who can be held, loved and enjoyed. The bird figure on the left can be interpreted as Lee’s

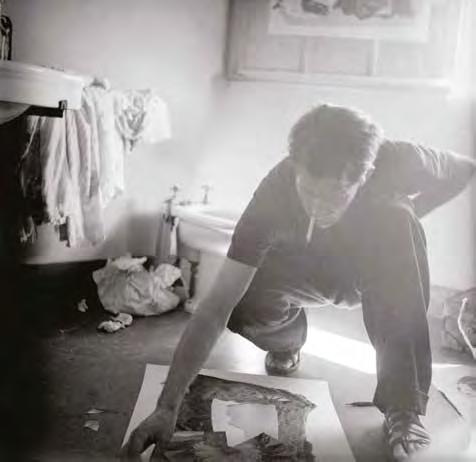

le F t : Roland working on one of his first postcard collages, Hotel Vaste Horizon, Mougins, France 1937 by Lee Miller.

opposite top : Magnetic Moths, 1938, collage, by Roland Penrose.

opposite bottom : The real Woman, 1937, collage, by Roland Penrose.

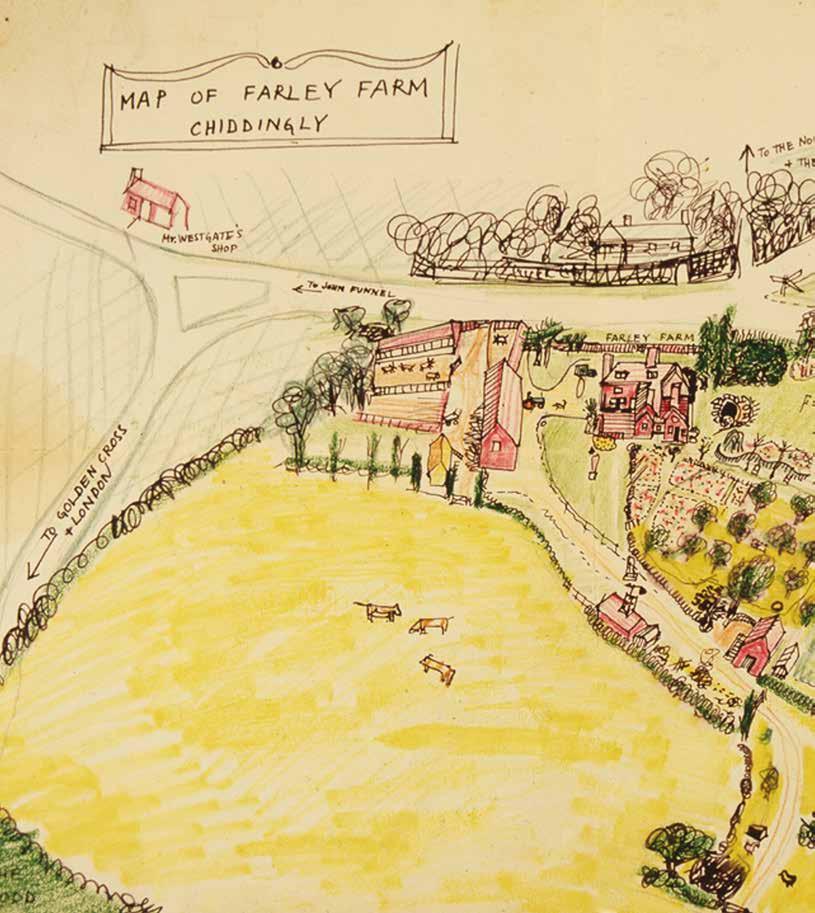

I have been told that I hated my first few weeks at Farleys. I was only a year and a half old at the time, so I have to rely on Roland’s opinion. He said I could not stand the cold, and was frightened by the sound of creaking timbers and slamming doors when the gales blew. It was March 1949 and there was a tremendous postwar shortage of building and furnishing materials, so few rooms had carpets or curtains. It was to be several years before Lee could scrounge her requirements, even with all her contacts in the world of fashion. So the wind whistled through the old casement windows and the cracks between the floorboards, particularly in the sitting room, which was over the cellar. Fortunately the rest of the ground floor was made of brick laid on the earth in the old Sussex tradition, which although prone to dampness in the winter at least kept the draughts out. Decades of scrubbing followed more lately by waxing had given the surface a smooth and mellow texture, cool to bare feet in the summer. The kitchen was the constant focus of activity, particularly in winter when the warmth of the old Raeburn stove drew everyone like a magnet.

The purchase of Farleys was funded by the sale of 36 Downshire Hill. Roland and Lee bought a small two-bedroomed flat at 11a Hornton Street in Kensington, where they would stay during the week, returning on Fridays with more carloads of paintings or furniture. Once the household was established, I stayed at Farleys with the current nanny drawn for the most part from the vast ranks of women widowed in the war. Many had a sadness I never understood, but one, Gati, was memorably kind and cheerful. In the early days, the pivotal characters in my life were the farm staff and an adoring Labrador dog named Heather. They had permanence and reliability, except for Heather in thunderstorms. She would disappear and hide under the bed, quivering with fright.

Roland saw the potential of the modest farmhouse garden with its old orchard, but realized that years of work would be needed to transform it into the vision he had in mind. He took on Grandpa White, a wise old countryman from the village, but the work was soon more than he could handle, so Fred Baker was also hired. He was soon to be Grandpa White’s grandson-in-law, and welcomed the prospect of a tied cottage on the farm as a home for him and his bride Joan.

left : Map of Farley Farm, c1952, ink and watercolour on paper, by Roland Penrose.

opposite top left : Oils and condiments in Lee Miller’s pantry at Farleys.

opposite top R ig H t : Lee Miller’s cooking utensils in Farleys’ kitchen drawers.

opposite bottom : A Picasso tile resides above the AGA, in the kitchen at Farleys that was fitted in 1954.

top left : 1950’s Shred-O-Mat.

top middle : Androck hand whisk.

top R ig H t : Vintage masher.

bottom left : 1950’s Dale Ware saucepans.

bottom R ig H t : 1950’s Langner Hostess Cake Breaker.

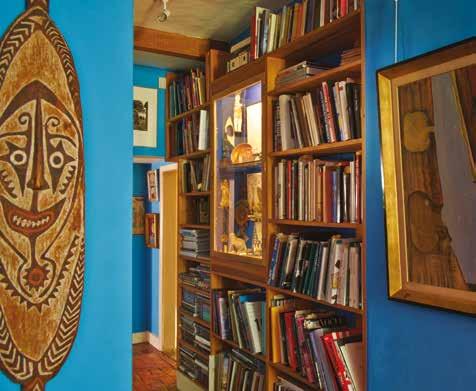

opposite : Front Hall, Farleys House, Sussex, England.

right top : The glass cabinet is housed in the passage presided over by an ancestral wooden plaque from Papua New Guinea.

right bottom : It is the curiosity value of items such as the mumified rat that earns them their place in the collector’s cabinet in the passage. Curios include a pottery chicken from Honduras, a Hopi Indian doll from Arizona, Bakota reliquary from Africa and a dead May-bug.

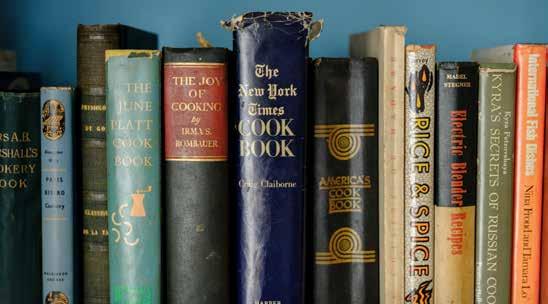

left : Lee’s desk in her library, built to house her growing number of cook books.

right top : The fireplace remains unfinished as Lee preferred it, in her library at Farleys House.

right bottom : Lee’s writing ephemera on her desk in her library.

THE END OF AN ERA

If I had it all over again I’d be even more free with my ideas – with my body and my affection. Above all I’d try to find some way of breaking down, through the silence that imposes itself on me in matters of sentiment – I’d have let you, Roland, know how much and how passionately and how tenderly I love you.

LEE MILLER, WRITTEN WHILST AWAITING THE BIRTH OF HER SON, 9 SEPTEMBER 1947

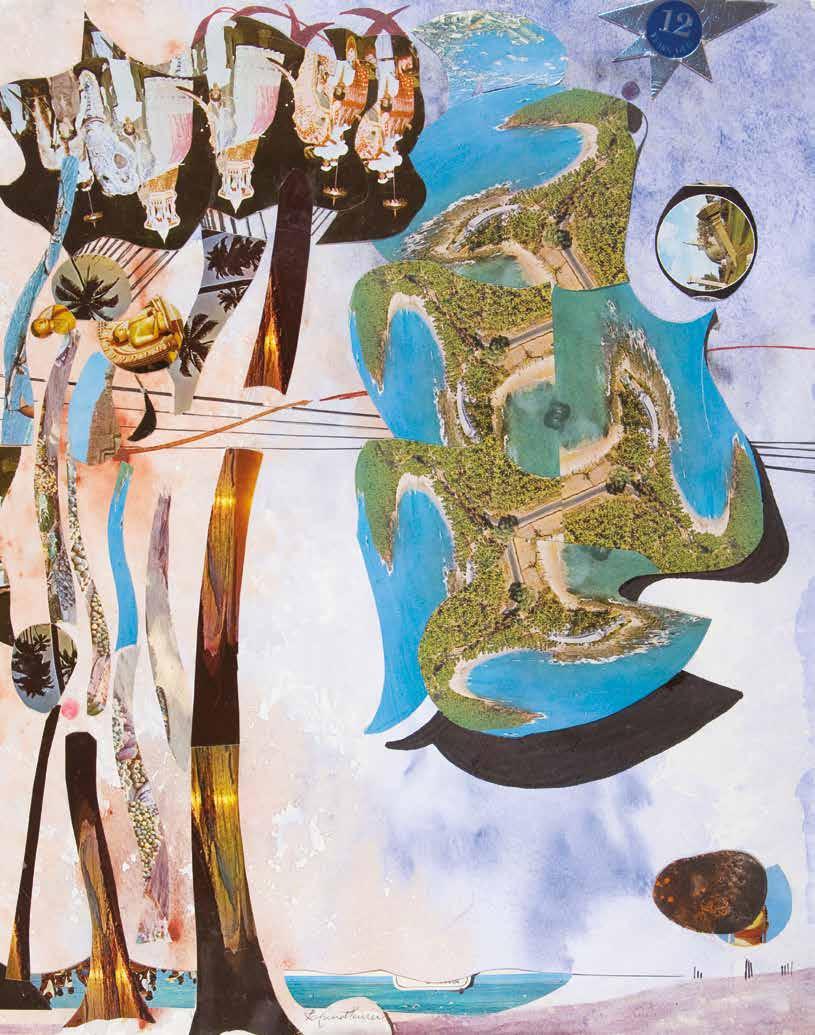

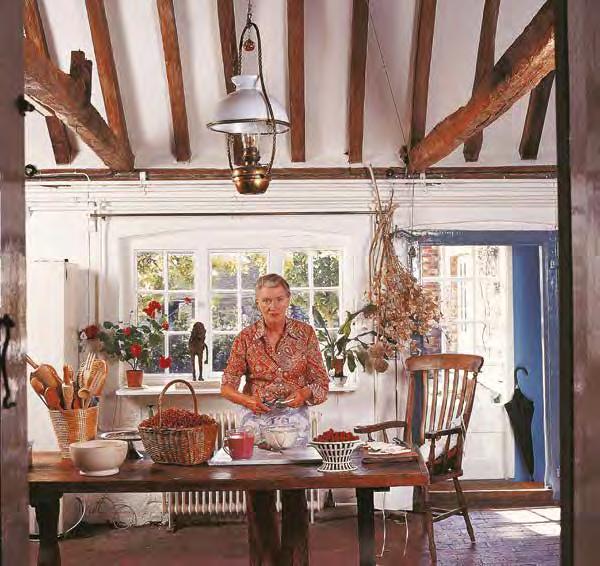

opposite : How do you like Sri Lanka, Sir?, 1981, collage, by Roland Penrose. above : Lee in the old kitchen, photographed for House and Garden 1973.

opposite : The fountain, c1963, copper, in the lily pond seen from the kitchen windows was built by Roland and Antony Penrose. right : Barbarella’s Bra, c1979, barbed wire, by Antony Penrose. Made as a birthday present for Roland who was satisfactorily shocked.

work on the farm. The essence of life at Farleys continued intact, though not without some major changes.

Patsy remained the central pivot of the home, but was now alone as her daughter Georgina was in Botswana, working on an aid project. Georgina and I had resolved the bitter jealousies aroused by her arrival at Farleys, and developed a special affection that endures to this day.

Lee and I had elevated our parent-teenager conflict to all-out guerrilla warfare. Deeply mistrustful of any truce, I ruthlessly repelled Lee’s peace overtures. Paradoxically, she unfailingly made my friends welcome, and they adored her, often affording her respect and affection in ways I found altogether bewildering. Roland and I still bumbled on in an affectionate but rather distant way, neither of us really understanding the other, but enjoying doing things together.

One of our best joint projects was the fountain that stands in the lily pond in front of the kitchen. We made it during a period of reconciliation that followed a bad time in my school career. He made the maquette and, helped by a firm of sheet metal workers in Eastbourne, I built the fountain, with Roland doing much of the final detailing. It is made of copper, a metal that is kind and forgiving to work and has a quality of solid durability, symbolic of the relationship I began to build with Roland. In some ways I had a role as his squire. When required I would step into his world of art, and find myself in situations and places that so differed from my own chosen profession that at times I wondered if I was still on the same planet. I enjoyed these temporary flirtations with art but, at that point in my life, it was not a love match – although now art is as vital to me as breathing.

An event that shook us all to the core and changed our way of life fell at Easter 1969. While we were all enjoying a quiet break at Farleys, the news came through that 11a Hornton Street had been burgled. Roland, Lee and I jumped on the next train to London and arrived to find a scene of indescribable desolation, with empty frames and broken glass strewn around, the chaos calmly surveyed by Pee Cee, Lee’s beloved cat. Twenty-six paintings including four by Picasso, and others by De Chirico, Ernst, Miró, Braque, Man Ray and Magritte had been stolen. The thieves demanded a ransom; they had calculated that the raid would earn them a payoff from

the insurers. However Roland had not insured the paintings for their full value for theft, believing that no one would steal works so recognizable that they were unsaleable. The thieves had also not reckoned on Roland’s moral strength. The Quaker in him came to the fore, and on BBC television’s Panorama he boldly stated he would not pay a ransom. The waiting game became a war of attrition as the thieves tried to wear down Roland’s resolve. Roland gave them just enough encouragement to buy time for the police to set up a complicated sting. When it came, the long-awaited operation nearly went badly wrong.

The thieves, accompanied by a secret informer and tailed by plainclothes police, arrived at the derelict building where the paintings were hidden, but when on seeing workmen there drove straight on. Meanwhile the workmen had started a bonfire for all the rubbish. Luckily they paused when they found the paintings, and took one round the corner to an art shop where the astonished owner identified Picasso’s Woman Weeping . Roland learned of the paintings recovery from the front page of the Evening Standard . He was called to Chelsea police station where on finding the paintings locked in the cells for safekeeping he wept for joy. The police later arrested most of the gang, and some were jailed for our burglary and other offences. The informer was lucky to escape with his life, and the workmen got a reward.

A few days later I went to the Tate Gallery where Stefan Slabczynski, the well-known restorer, was tenderly administering

In its heyday, Farleys House, the home of American photographer Lee Miller ad British artist Roland Penrose in Sussex, southern England, represented one of the most important collections of modern art in Britain, with a list of visitors that reads like a Who’s Who of twentiethcentury artists – from Pablo Picasso and Max Ernst, Man Ray and Joán Miró, to Paul Éluard and Henry Moore. In this beautifully illustrated book, Miler’s and Penrose’s son, Antony Penrose, opens the door of Farleys House to allow a rare glimpse inside a remarkable house, boasting a superb art collection and serving for over thirty years as the home of two talented artists at the forefront of the Surrealist movement.

Famed for her beauty, Lee Miller was a former lover and pupil of the Surrealist photographer Man Ray. Her work for Vogue in New York, Paris and London – first as a model, then as a photographer and later as a war correspondent – established her as an uncompromising photographer of international repute. Her post-war years are noted for her portraits of artists, many of whom were photographed at Farleys House. Today her work is still exhibited and admired worldwide.

Roland Penrose studied art in Paris and counted Paul Éluard, André Breton, Max Ernst and Pablo Picasso among his friends. He became a Surrealist painter, and subsequently mounted the 1936 International

Surrealist Exhibition in London, which led to the establishment of the movement in Britain. One of the co-founders of the British Institute of the Contemporary Arts in London, he became well known for organising the Arts Council exhibitions of Picasso, Ernst and Miró, and for writing biographies of Picasso, Ernst and Miró, Man Ray and Tapiés.

Today his paintings hang in major galleries all over the world.

Specially commissioned photographs by Tony Tree and Jim Holden are presented alongside photographs by Lee Miller, telling the story of Farleys House and its inhabitants over thirty-five years. Antony Penrose offers personal anecdotes of the dramas and outrageous surprises that were part of everyday life growing up in an unconventional milieu and enjoying visits from some of the most flamboyant and famous artists of the day. The book also documents the internationally renowned collection of painting and sculpture that Miller and Penrose established in their home – in part composed of artistic mementoes of their friends, like the tile in the kitchen by Picasso or the poem on the stairs by Éluard.

Blending great art with original photography and intimate recollection, this book provides a revealing first-hand account of a Surrealist artists’ colony and the story of one of the most fascinating collections of modern art ever assembled.