25 26 SEASON

We’ve

25 26 SEASON

We’ve

We’re honored they’ve done the same for us.

Ranked

We believe the connection between you and your advisor is everything. It starts with a handshake and a simple conversation, then grows as your advisor takes the time to learn what matters most–your needs, your concerns, your life’s ambitions. By investing in relationships, Raymond James has built a firm where simple beginnings can lead to boundless potential.

ONE HUNDRED THIRTY-FIFTH SEASON

CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA

KLAUS MÄKELÄ Zell Music Director Designate | RICCARDO MUTI Music Director Emeritus for Life

Thursday, September 18, 2025, at 7:30

Friday, September 19, 2025, at 1:30

Nikolaj Szeps-Znaider Conductor and Violin

Teng Li Viola

MOZART

Sinfonia concertante in E-flat Major, K. 364

Allegro maestoso

Andante

Presto

NIKOLAJ SZEPS-ZNAIDER

TENG LI

INTERMISSION

ELGAR

Symphony No. 2 in E-flat Major, Op. 63

Allegro vivace e nobilmente

Larghetto

Rondo

Moderato e maestoso

These concerts are generously sponsored by Zell Family Foundation. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association acknowledges support from the Illinois Arts Council.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra thanks Zell Family Foundation for sponsoring these performances.

COMMENTS by Phillip Huscher

WOLFGANG MOZART

Born January 27, 1756; Salzburg, Austria

Died December 5, 1791; Vienna, Austria

Although Mozart regularly wrote concertos for his own public appearances as a pianist, in the late 1770s he became fascinated with the idea of concertos for more than one soloist. As a kind of preview, he composed a concertone (literally a big concerto) for two solo violins with a prominent oboe part in 1774. And then, in a sudden outpouring so typical of this young composer, came a concerto for flute and harp, followed by one for two pianos, and finally this work featuring solo violin and viola—all three of them written in 1778 and 1779. But that is not all: Mozart also began a concerto for piano and violin in 1778 and another for violin, viola, and cello the following year and abandoned both scores when the concerts for which they were intended were canceled.

This sinfonia concertante the unfinished work for violin, viola, and cello bears the same title—is, as the name suggests, something of a genre-blender, interweaving the front-of-stage virtuosity of the concerto with the depth and importance of the symphony. Mozart knew both solo instruments exceedingly

COMPOSED 1779

FIRST PERFORMANCE date unknown

INSTRUMENTATION solo violin and viola, 2 oboes, 2 horns, strings

CADENZAS Mozart

APPROXIMATE

PERFORMANCE TIME 30 minutes

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES

January 13 and 14, 1905, Orchestra Hall. Ludwig Becker and Franz Esser as soloists, Frederick Stock conducting

August 3, 1944, Ravinia Festival. John Weicher and Milton Preves as soloists, Désiré Defauw conducting

MOST RECENT

CSO PERFORMANCES

August 8, 2021, Ravinia Festival. Stella Chen and Matthew Lipman as soloists, Yue Bao conducting May 12, 13, and 14, 2022, Orchestra Hall. Stephanie Jeong and Julian Rachlin as soloists, Julian Rachlin conducting

from top : Wolfgang Mozart, from a detail of the family portrait by Johann Nepomuk della Croce (1736–1819), ca. 1780, now in the collection of the Mozarteum Foundation, Salzburg, Austria

Mozart at the keyboard and violinist Thomas Lindley (1756–1778) featured in a painting with members of the Gavard des Pivets family. Florence, Italy, 1770

well. He was himself a highly accomplished violinist, and, perhaps more significantly, the son of the man who wrote the most important violin treatise of the day (and one, in fact, that was still in use into the twentieth century). But Wolfgang often picked the viola when he played chamber music, partly because, like many composers, he enjoyed taking a middle voice in the texture, and possibly as a kind of rejection of his father Leopold’s identification with the violin. In writing for two instruments he knew so well,

Phillip Huscher talks with Principal Viola Teng Li

PH: Mozart’s Sinfonia concertante is one of the most extraordinary concertos in his entire output. Do you recall when you first heard it?

TL: I first heard the piece in China while I was studying at the Central Conservatory. I first performed it as an orchestra member at the Curtis Institute in 2002. I remember being asked to bring out the harmonic changes in the second viola part.

Mozart makes a choice only a very thoughtful composer would: he emphasizes the subtle differences in color and timbre, rather than the simple differences in range, between them. The dialogue Mozart writes for them is as engaging and complicated as that of two characters in one of his operas. Mozart enriches the orchestral fabric by dividing the violas into two sections, much the way that he creates a new sound world in some of his greatest chamber music by adding an extra viola to the standard string quartet.

When did you first play the solo part?

It was in 2000. I was featured as a soloist with the National Chamber Orchestra, along with violinist Eunice Keem. Eunice and I were both first-prize winners at the Johansen International Competition, and the performance was part of our award.

“I’ve played the Sinfonia concertante a few times, but this is the first time I’ve decided to follow Mozart’s original idea of tuning the viola a half step higher. I’ve heard that this will give the instrument a very different sound through more overtones from the sympathetic vibrations in the open strings.”

Mozart writes the three standard movements of the concerto form, which of course in his hands are never conventional in content, detail, or overall architecture. The first is spacious and majestic, with the powerful drama of having not one but two soloists pitted against the orchestra. Their joint entrance, sweeping in from the background on a sustained high E-flat, is magical. (In George Balanchine’s highly musical 1947 choreography, the two principal ballerina roles,

corresponding to the solo instruments, leave the stage in the passages when the violin and viola are silent.) The central Andante is a deeply moving duet. There is an unexpected darkness in this music—one of Mozart’s relatively rare minor-mode slow movements—as if Mozart were finally processing the death of his mother in Paris the previous year. The finale is, almost by necessity after the deeply probing Andante, light, jovial, and even mischievous.

Do you have a treasured recording of the piece?

I grew up with Gidon Kremer and Kim Kashkashian’s recording. It was one of the first video recordings I ever watched. Ms. Kashkashian has been a role model of mine ever since.

Is this the first time you have followed Mozart’s original tuning?

I’ve played the Sinfonia concertante a few times, but this is the first time I’ve decided to follow Mozart’s original idea of tuning the viola a half step higher. I’ve heard that this will give the instrument a very different sound through more overtones from the sympathetic vibrations in the open strings. I predict the viola will have a brighter sound, which will change the colors on Mozart’s canvas. I’m very much looking forward to this experience.

When Mozart played string quartets, he always chose to play viola rather than violin. Why do you think he had such a fondness for the instrument?

I remember going to Mozart’s house in Salzburg and seeing his viola on display. He shows his love for the viola through his music. I sometimes wonder if he preferred the viola because its register is much closer to that of the human voice. I feel it is much easier for the viola to imitate the human voice rather than the violin. I’ve imagined Mozart singing some of the melodies in this piece!

The interplay of the violin and viola throughout this work is almost theatrical, like some of the great duets in the operas. Do you feel a sense of drama in the way these two instruments converse?

Yes! There is a sense of drama throughout the whole piece. The musical tension develops as the violin and viola communicate back and forth. I can’t wait to hear how Nikolaj is going to react to me, and together we’ll keep this operatic writing alive.

In the slow movement, your two lines overlap in ways that keep the music going in an almost unbroken melody. Is that difficult to sustain over such a long stretch?

Yes, it can be a challenge to sustain the long line over the slow tempo. The most important thing for me is to know how long each phrase is, as it’s through these long phrases that we build the structure of the entire movement. I also love that there are times when the phrase is made up of our two solo lines trading on and off, and I always remind myself to allow the music to flow through the exchanging lines of our instruments.

For many musicians, Mozart epitomizes the pure classical style. Do you think of his music as formal and straitlaced?

For me, Mozart is one of the most emotional composers. His use of rhythm and harmony is never conventional. As performers, we can decide what kind of techniques to use to bring Mozart’s music alive. One might decide whether to use vibrato, lots of light air in the bow, or heavier strokes. No matter what technical tools we end up using, Mozart’s music always comes across as expressive.

EDWARD ELGAR

Born June 2, 1857; Broadheath, near Worcester, England

Died February 23, 1934; Worcester, England

When Elgar’s Symphony no. 1 was introduced in Manchester in December 1908, it was immediately hailed as a long-awaited landmark—as England’s First Symphony in effect, the first true masterpiece England had produced to set beside the great works in that form by Mozart, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Schumann, and, more recently, Brahms, Dvořák, and Tchaikovsky. The accomplishment was extraordinary—fulfilling the promise Bernard Shaw expressed when he first heard Elgar’s Enigma Variations nearly a decade earlier: “I sat up and said ‘Whew!’ I knew we had got it at last.” But the burden was great. Eightytwo performances of the new symphony were given in six countries the next year. Elgar’s Violin Concerto, which premiered in November 1910, extended the composer’s triumphal run and predicted more great things to come. Then, six months later, Elgar’s Second Symphony fell flat. The hall wasn’t full; the response was tepid. “They sit there like a lot of stuffed pigs,” Elgar said to the concertmaster as they left the stage.

By 1911, Elgar held a position in musical life in England that had long gone unoccupied. His first Pomp and Circumstance March, composed in 1901, had already become a huge hit with the public, and, once he was knighted in 1904, he was recognized everywhere as England’s greatest composer. But Elgar was too insecure and too unstable—he suffered all his life from bipolar disorder—to take failure in stride. Success had not come easily or early in his career. He was already forty-two when the Enigma Variations were first played in London—the event that sent ripples of excitement throughout the music world. Even after he was a national figure, with Sir appended to his name, he continued to refer to himself simply as “a piano-tuner’s son.”

Although Elgar was devastated by the public response to his new symphony—particularly after the enthusiasm that greeted his two previous big works, the First Symphony and the Violin

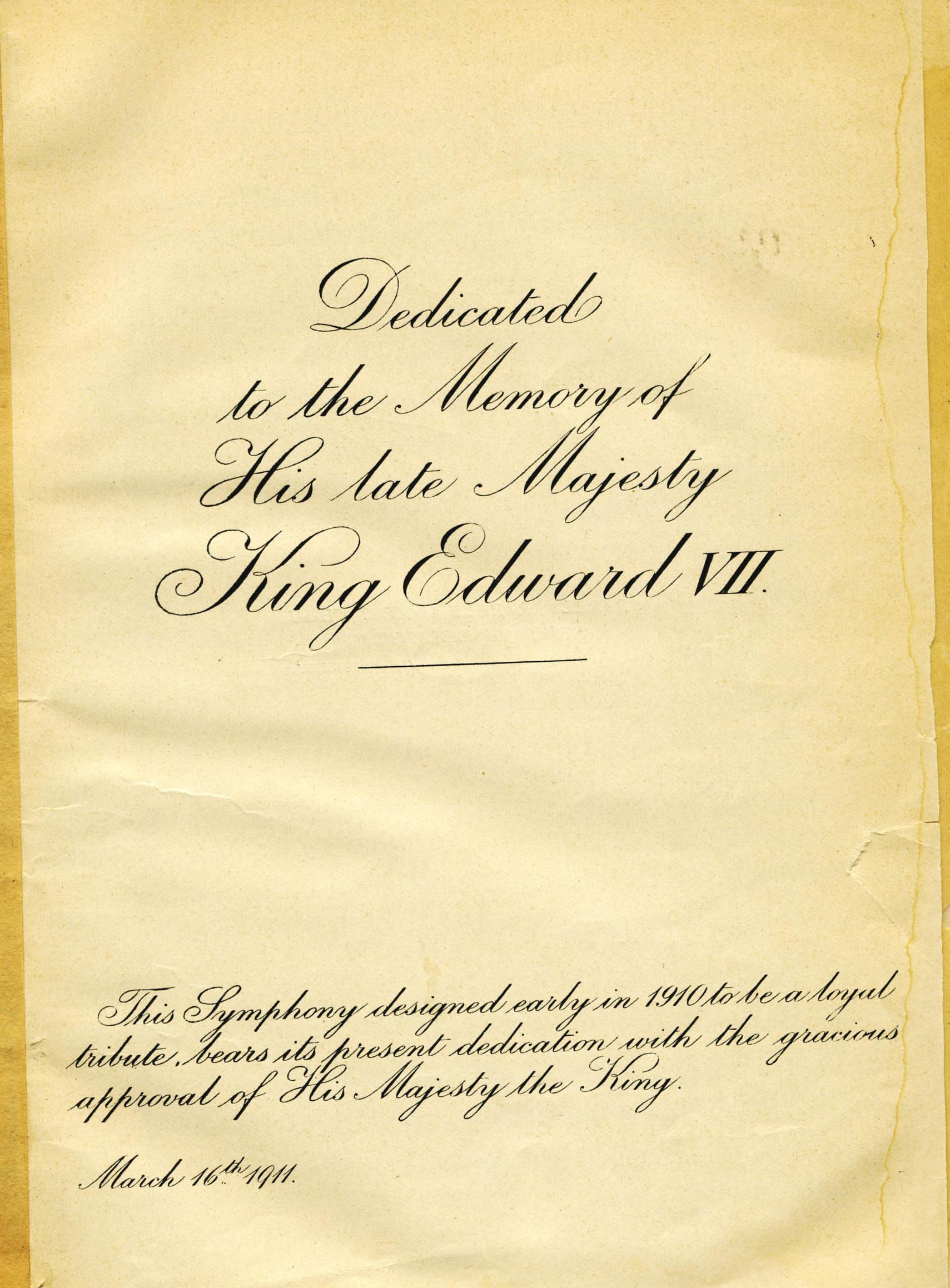

this page, from top: Edward Elgar, portrait, ca. 1904, Russell & Sons Photographers, London, England | Elgar and his wife, Caroline Alice (1848–1920), who first came to the composer as a piano student in 1886 and later married him in 1889 | opposite page: Dedication page of Elgar’s Symphony no. 2 in honor of King Edward VII (1841–1910), 1911

COMPOSED 1910–11

FIRST PERFORMANCE

May 24, 1911; London, England. The composer conducting

INSTRUMENTATION

3 flutes (3rd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes and english horn, 2 clarinets, E-flat clarinet and bass clarinet, 2 bassoons and contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, snare drum, cymbals, 2 harps, strings

APPROXIMATE PERFORMANCE TIME 54 minutes

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES

January 12 and 13, 1912, Orchestra Hall. Frederick Stock conducting June 30, 1951, Ravinia Festival. William Steinberg conducting

MOST RECENT CSO PERFORMANCES

April 1, 3, and 6, 2010, Orchestra Hall. Sir Mark Elder conducting

Concerto—there also is reason to believe that he overreacted. The critics spoke of an enthusiastic reception and wrote glowingly of the symphony itself (The Telegraph said it was decidedly better than the First). Attendance was low, it has been suggested, because ticket prices were unusually high and the music was all new (the other premieres were by Walford Davies and Granville Bantock)—always a fatal combination, even with a name like Elgar’s on the bill. Nonetheless, when repeat performances in the days following the premiere were even more poorly attended, Elgar simply refused to accept his fee from the orchestra.

Elgar’s wife Alice was the first to rank the Second Symphony high in her husband’s output: “It seems one of his very greatest works, vast in design and supremely beautiful.” It is one of Elgar’s encyclopedic works that knits together many of his personal themes, from his earliest schoolboy years, when he wrote that he was, above all, “longing for something very great,” to his current life, a time of true attainment, and it suggests a man of great contradictions and complexities. It recalls the lines written by Cecil Day-Lewis (perhaps better known today as the father of the actor Daniel Day-Lewis) in The Gate to describe Elgar:

The stiff, shy, blinking man in a norfolk suit: The martinet: the gentle-minded squire: The piano-tuner’s son from Worcestershire: The Edwardian grandee: how did they consort

In such luxuriant themes?

When Elgar set out to write his first symphony, he said, in a lecture at Birmingham University, that the symphony without a program was “the highest development of art,” words pointedly meant to justify his choice at a time when many composers had given up on the form—this was, after all, the era of Strauss’s pictorial tone poems and Debussy’s bold new canvases. (The first decade of the twentieth century also was the age of Mahler’s symphonies—his Seventh premiered in Prague just three months before Elgar’s first, and the Eighth was first performed two years later in Munich, the year before Elgar began his Second Symphony. But England was largely unaware of Mahler at the time.) And 1910, the year Elgar began work on his Second Symphony, also was the year Stravinsky began sketching The Rite of Spring. Times were changing even more rapidly than Elgar suspected.

Elgar wrote a motto from Shelley—“Rarely, rarely comest thou, / Spirit of Delight”—at the top of his keyboard draft and at the end of the full score of the symphony. He later said that “The spirit of the whole work is intended to be high and pure joy: there are retrospective passages of sadness, but the whole of the sorrow is smoothed out and ennobled in the last movement.” He also spoke of the symphony as representing the “passionate pilgrimage” of the soul.

“I have worked at fever heat, and the thing is tremendous in energy,” Elgar said, and the Second Symphony begins with a veritable explosion of sounds and ideas. The entire first movement is a very large paragraph, rich in detail and assured in its large-scale architecture. “The germ of the work,” Elgar wrote, “is in the opening bars—these in a modified form are heard for the last time in the closing bars of the movement.” Those few wild, swashbuckling measures of music—the “Spirit of Delight” motto—do indeed set the entire symphony off on its great adventure. Through the first movement, with its complexity of conflicting emotions and unexpected musical detours, its restless energy, and mastery of long-range planning, this music suggests a parallel with that of Mahler, who died just six days before the premiere of Elgar’s Second Symphony.

“I have written the most extraordinary passage,” Elgar wrote to his dear friend Alice StuartWortley, who is the secret muse of the Second Symphony, regarding the spooky, haunted development section. (It came as second nature to the composer of the Enigma Variations to encode his music with personal references, and this symphony is filled with music Elgar identified with Alice Stuart-Wortley—the “other” Alice in his life, as opposed to his own “Lady Alice”—including a theme labeled “Windflower,” his nickname for her. As Elgar wrote to a friend, once again quoting Shelley: “I do but hide / Under these notes, like embers, every spark / Of that which has consumed me”). With its muted violins and muffled horn calls, the unexpected mood shift of the development section suggests what Elgar called “a sort of malign influence

wandering thro’ the summer night in the garden.” The recapitulation regains the reckless energy and the spirit of delight.

The magnificent, deeply moving orchestral dirge Elgar places next is clearly a homage to Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony, also in E-flat and with its own grand marcia funebre. At the time of the premiere, the public thought it was meant as funeral music for Edward VII, who had died a year earlier. Elgar even dedicated the symphony “to the memory of His Late Majesty King Edward VII.” But, in fact, the music came first, sketched in part as early as 1904, when Elgar learned of the death of his good friend Alfred E. Rodewald. The movement is broad, eloquent, and surprisingly complex in imaginative detail for such slow and somber music—midway through, for example, the oboe plays rippling arabesques against the off-beat “drumbeat,” itself a singular combination of low winds, brass, drums, harps, and ricocheting strings. “I have written out my soul,” Elgar said to a friend.

The high-speed scherzo, sketched in the Piazza San Marco in Venice, amid the bustle of pigeons and tourists, brings the relief of spirited, genial music. But eventually it is haunted by the ghosts of the first movement, and the mood turns sour. The orchestral writing is brilliant throughout.

The finale begins innocently as it works its way toward a grand, striding theme Elgar labeled “Hans himself,” after the celebrated conductor Hans Richter, who had led the premiere of Elgar’s First Symphony. The music moves forward briskly, building in energy and excitement, promising a triumphant, all-stops-out conclusion—the kind of thing Elgar did so brilliantly in his First Symphony. Instead, however, Elgar writes a soft, beautiful, and unexpected coda. The opening of the symphony reappears fleetingly, its theme sounding lovelier than ever. Gradually the music settles into a mood of deep, if nostalgic, serenity and fades. At the very end, Elgar suggests the final cadences of Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde, which so moved him when he heard it for the first time at a memorial concert

in 1883, the year Wagner died, that he wrote in his program book: “I shall never forget this.”

Postscript. Although his second symphony had followed quickly on the heels of the first, Elgar was in no frame of mind to consider writing a third. For years, his friend Bernard Shaw continued to badger him to begin a new symphony and finally persuaded the BBC to commission it to honor Elgar’s seventy-fifth birthday celebrations in 1932. During the last year of his life, Elgar jotted down ideas, as if compiling the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. When he died in February 1934, he left more than 130 pages of sketches—a puzzle that could not be finished. At the time, it appeared that Elgar’s Third Symphony had in fact “died with the composer,” as Shaw suggested, and the material lay untouched for more than half a century. But eventually interest in the sketches picked up, fanning speculation that something might be made of them and culminating finally in the work of London-born composer

Anthony Payne. His “elaboration” of the material into a fully performable score was premiered, to great enthusiasm, in London in 1998, sixty-four years after the composer’s death, and presented by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra the following year.

A footnote. Frederick Stock, our orchestra’s second music director, introduced both of Elgar’s symphonies to Chicago within a year of their world premieres in England. Elgar had already been in Chicago in 1907 to conduct the Orchestra in three of his works: In the South, the Enigma Variations, and the first of his Pomp and Circumstance Marches. He said that the orchestra surpassed all his expectations and that there was none better in Europe.

Phillip Huscher has been the program annotator for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra since 1987.

You can order drinks and snacks before the performance or during intermission at various bars located throughout Symphony Center, including the Bass Bar in the Rotunda and most of the lobby spaces in Orchestra Hall.

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES

November 24 and 25, 2000, Orchestra Hall. Sibelius’s Violin Concerto, Daniel Barenboim conducting

July 16, 2015, Ravinia Festival. Mozart’s Violin Concerto no. 3 (conducting from the violin) and Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique

December 21, 22, and 23, 2017, Orchestra Hall. Beethoven’s Violin Concerto (conducting from the violin) and Shostakovich’s Symphony no. 5

MOST RECENT CSO PERFORMANCES

March 27 and 29, 2025, Orchestra Hall. Bruch’s Violin Concerto no. 1 (conducting from the violin), Boulez’s Livre pour cordes, and Schumann’s Symphony no. 3

The 2025–26 season marks Nikolaj Szeps-Znaider’s sixth as music director of the Orchestre National de Lyon, a partnership that has been extended until 2026–27.

Szeps-Znaider regularly features as guest conductor with the world’s leading orchestras, such as the New York Philharmonic, Philadelphia Orchestra, London Symphony, and Royal Stockholm Philharmonic. His return to the Chicago Symphony Orchestra continues a flourishing relationship.

On the operatic front, following a successful debut conducting Mozart’s The Magic Flute at the Dresden Semperoper, Szeps-Znaider was immediately re-invited to lead Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier. He recently made debuts with the Royal Danish Opera, Bavarian State Opera, and the Zurich Opera House.

Also a virtuoso violinist, Szeps-Znaider maintains his reputation as one of the world’s

leading exponents of the instrument with a busy calendar of concerto and recital engagements. This season, he makes return appearances with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra Amsterdam, London Philharmonic, and Danish Radio Symphony Orchestra, as well as with the New World and St. Louis symphony orchestras. He also embarks on an extensive European recital tour with pianist Daniil Trifonov.

Szeps-Znaider boasts an extensive discography of much of the core repertoire for violin, including a critically praised complete collection of Mozart’s violin concertos with the London Symphony Orchestra, which he directs from the violin. Other notable recordings include Nielsen’s Violin Concerto with the New York Philharmonic and Alan Gilbert, Elgar’s Concerto in B minor with the Dresden Staatskapelle and Sir Colin Davis, award-winning recordings of the concertos by Brahms and Korngold with the Vienna Philharmonic under Valery Gergiev, the concertos by Beethoven and Mendelssohn with the Israel Philharmonic and Zubin Mehta, Prokofiev’s Concerto no. 2 and Glazunov’s Concerto in A minor with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and Mariss Jansons, and Mendelssohn’s concerto on DVD with the Gewandhaus Orchestra and Riccardo Chailly. Szeps-Znaider has also recorded all of Brahms’s works for violin and piano with Yefim Bronfman.

Szeps-Znaider plays the 1741 “Kreisler” Guarnerius del Gesù instrument on extended loan by the Royal Danish Theatre through the generosity of the VELUX Foundations, the Villum Foundation, and the Knud Højgaard Foundation.

Nikolaj Szeps-Znaider is managed by Enticott Music Management in association with IMG Artists.

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES

October 24, 25, and 26, 2024, Orchestra Hall. Strauss’s Don Quixote, Sir Donald Runnicles conducting

Teng Li is an internationally celebrated soloist, chamber musician, and recording artist, the recipient of critical praise in publications such as the New York Times and BBC Music. In 2023 Li was appointed to the Paul Hindemith Principal Viola Chair of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra by Music Director Emeritus for Life Riccardo Muti, a post she assumed at the beginning of the 2024–25 season. She was principal viola of the Los Angeles Philharmonic from 2018 to 2024 and served for fourteen seasons as principal viola of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra.

She has appeared with premier ensembles throughout the world, including the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Toronto Symphony Orchestra, Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, National Chamber Orchestra, Munich Chamber Orchestra, Shanghai Opera Symphony Orchestra, and Esprit Orchestra.

Most recently, she was featured in acclaimed performances of Paganini’s Sonata per la grand viola with the Los Angeles Philharmonic and Lina González-Granados, as well as in Kancheli’s Styx with the Oklahoma City Philharmonic led by Alexander Mickelthwate.

Li is an ardent chamber musician with notable past engagements at the Marlboro, Santa Fe Chamber, Rome Chamber, and Moritzburg music festivals; Chamber Music Northwest; La Jolla Music Society SummerFest; ChamberFest Cleveland; and the prestigious Lincoln Center Chamber Music Society Two program (since renamed the Bowers Program). She has

performed at Carnegie Hall’s Weill Recital Hall and the 92nd Street Y Chamber Music Society in New York and collaborated closely with the Guarneri Quartet, joining the ensemble in concerts during its final season in 2008–09. She is a founding member of the Rosamunde Quartet, together with violinists Noah BendixBalgley and Shanshan Yao and cellist Nathan Vickery, with whom she has given performances and master classes throughout the United States and Canada.

Li’s interpretations of chamber music works can be heard on several critically acclaimed recordings, among them 1939, her album for Azica Records with violinist Benjamin Bowman and pianist Meng-Chieh Liu. Her discography also includes credits with the Los Angeles Philharmonic and the Toronto Symphony, most notably on the latter’s Juno Award–winning album of works by Vaughan Williams for Chandos, which features Li in a performance of Flos campi.

Li has won top prizes at the Johansen International Competition, Holland-America Music Society Competition, Primrose International Viola Competition, Klein International String Competition, and the ARD International Music Competition in Munich. She was also a winner of the Astral Artistic Services 2003 National Auditions.

A committed educator, Li has taught at the Colburn School, University of Toronto, Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto, and the Montreal Conservatory of Music and joined the faculty of Roosevelt University’s Chicago College of Performing Arts in the 2024–25 academic year. In addition, she teaches at the Sarasota Music Festival and Morningside Music Bridge. Li is a graduate of the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing and the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, where she studied with Michael Tree, Joseph de Pasquale, and Karen Tuttle.

A fundraising event presented by the League of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association, featuring Zell Music Director Designate Klaus Mäkelä and violist Antoine Tamestit.

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 17

11:00 am | Guest Check-In

11:30 am | Luncheon

12:30 pm | Program

UNION LEAGUE CLUB OF CHICAGO

Presidents Hall | 65 W. Jackson Blvd., Chicago, IL 60604

TICKETS $250

For event tickets and more information, visit cso.org/fallinlove.

HOSTED BY

Sarah Good, President

Sharon Mitchell, Vice President of Fundraising

Mimi Duginger and Margo Oberman, Co-Chairs

Contact Brent Taghap at taghapb@cso.org with event-related questions.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra—consistently hailed as one of the world’s best—marks its 135th season in 2025–26. The ensemble’s history began in 1889, when Theodore Thomas, the leading conductor in America and a recognized music pioneer, was invited by Chicago businessman Charles Norman Fay to establish a symphony orchestra. Thomas’s aim to build a permanent orchestra of the highest quality was realized at the first concerts in October 1891 in the Auditorium Theatre. Thomas served as music director until his death in January 1905, just three weeks after the dedication of Orchestra Hall, the Orchestra’s permanent home designed by Daniel Burnham.

Frederick Stock, recruited by Thomas to the viola section in 1895, became assistant conductor in 1899 and succeeded the Orchestra’s founder. His tenure lasted thirty-seven years, from 1905 to 1942—the longest of the Orchestra’s music directors. Stock founded the Civic Orchestra of Chicago— the first training orchestra in the U.S. affiliated with a major orchestra—in 1919, established youth auditions, organized the first subscription concerts especially for children, and began a series of popular concerts.

Three conductors headed the Orchestra during the following decade: Désiré Defauw was music director from 1943 to 1947, Artur Rodzinski in 1947–48, and Rafael Kubelík from 1950 to 1953. The next ten years belonged to Fritz Reiner, whose recordings with the CSO are still considered hallmarks. Reiner invited Margaret Hillis to form the Chicago Symphony Chorus in 1957. For five seasons from 1963 to 1968, Jean Martinon held the position of music director.

Sir Georg Solti, the Orchestra’s eighth music director, served from 1969 until 1991. His arrival launched one of the most successful musical partnerships of our time. The CSO made its first overseas tour to Europe in 1971 under his direction and released numerous award-winning recordings. Beginning in 1991, Solti held the title of music director laureate and returned to conduct the Orchestra each season until his death in September 1997.

Daniel Barenboim became ninth music director in 1991, a position he held until 2006. His tenure was distinguished by the opening of Symphony Center in 1997, appearances with the Orchestra in the dual role of pianist and conductor, and twenty-one international tours. Appointed by Barenboim in 1994 as the Chorus’s second director, Duain Wolfe served until his retirement in 2022.

In 2010, Riccardo Muti became the Orchestra’s tenth music director. During his tenure, the Orchestra deepened its engagement with the Chicago community, nurtured its legacy while supporting a new generation of musicians and composers, and collaborated with visionary artists. In September 2023, Muti became music director emeritus for life.

In April 2024, Finnish conductor Klaus Mäkelä was announced as the Orchestra’s eleventh music director and will begin an initial five-year tenure as Zell Music Director in September 2027. In July 2025, Donald Palumbo became the third director of the Chicago Symphony Chorus.

Carlo Maria Giulini was named the Orchestra’s first principal guest conductor in 1969, serving until 1972; Claudio Abbado held the position from 1982 to 1985. Pierre Boulez was appointed as principal guest conductor in 1995 and was named Helen Regenstein Conductor Emeritus in 2006, a position he held until his death in January 2016. From 2006 to 2010, Bernard Haitink was the Orchestra’s first principal conductor.

Mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato is the CSO’s Artist-in-Residence for the 2025–26 season.

The Orchestra first performed at Ravinia Park in 1905 and appeared frequently through August 1931, after which the park was closed for most of the Great Depression. In August 1936, the Orchestra helped to inaugurate the first season of the Ravinia Festival, and it has been in residence nearly every summer since.

Since 1916, recording has been a significant part of the Orchestra’s activities. Recordings by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus— including recent releases on CSO Resound, the Orchestra’s recording label launched in 2007— have earned sixty-five Grammy awards from the Recording Academy.

Tax-deductible donations do more than support the concerts you love — they impact more than 200,000 people through education and community engagement programs each year. Thanks to a generous matching grant, all gifts to the CSOA will be doubled. Make a difference with your gift today.

Klaus Mäkelä Zell Music Director Designate

Joyce DiDonato Artist-in-Residence

VIOLINS

Robert Chen Concertmaster

The Louis C. Sudler Chair, endowed by an

anonymous benefactor

Stephanie Jeong

Associate Concertmaster

The Cathy and Bill Osborn Chair

David Taylor*

Assistant Concertmaster

The Ling Z. and Michael C.

Markovitz Chair

Yuan-Qing Yu*

Assistant Concertmaster

So Young Bae

Cornelius Chiu

Gina DiBello

Kozue Funakoshi

Russell Hershow

Qing Hou

Gabriela Lara

Matous Michal

Simon Michal

Sando Shia

Susan Synnestvedt

Rong-Yan Tang

Baird Dodge Principal

Danny Yehun Jin

Assistant Principal

Lei Hou

Ni Mei

Hermine Gagné

Rachel Goldstein

Mihaela Ionescu

Melanie Kupchynsky

Wendy Koons Meir

Ronald Satkiewicz ‡

Florence Schwartz

VIOLAS

Teng Li Principal

The Paul Hindemith Principal Viola Chair

Catherine Brubaker

Youming Chen

Sunghee Choi

Wei-Ting Kuo

Danny Lai

Weijing Michal

Diane Mues

Lawrence Neuman

Max Raimi

John Sharp Principal

The Eloise W. Martin Chair

Kenneth Olsen

Assistant Principal

The Adele Gidwitz Chair

Karen Basrak

The Joseph A. and Cecile Renaud Gorno Chair

Richard Hirschl

Daniel Katz

Katinka Kleijn

Brant Taylor

The Ann Blickensderfer and Roger Blickensderfer Chair

BASSES

Alexander Hanna Principal

The David and Mary Winton

Green Principal Bass Chair

Alexander Horton

Assistant Principal

Daniel Carson

Ian Hallas

Robert Kassinger

Mark Kraemer

Stephen Lester

Bradley Opland

Andrew Sommer

FLUTES

Stefán Ragnar Höskuldsson § Principal

The Erika and Dietrich M.

Gross Principal Flute Chair

Emma Gerstein

Jennifer Gunn

PICCOLO

Jennifer Gunn

The Dora and John Aalbregtse Piccolo Chair

OBOES

William Welter Principal

Lora Schaefer

Assistant Principal

The Gilchrist Foundation, Jocelyn Gilchrist Chair

Scott Hostetler

ENGLISH HORN

Scott Hostetler

Riccardo Muti Music Director Emeritus for Life

CLARINETS

Stephen Williamson Principal

John Bruce Yeh

Assistant Principal

The Governing

Members Chair

Gregory Smith

E-FLAT CLARINET

John Bruce Yeh

BASSOONS

Keith Buncke Principal

William Buchman

Assistant Principal

Miles Maner

HORNS

Mark Almond Principal

James Smelser

David Griffin

Oto Carrillo

Susanna Gaunt

Daniel Gingrich ‡

TRUMPETS

Esteban Batallán Principal

The Adolph Herseth Principal Trumpet Chair, endowed by an anonymous benefactor

John Hagstrom

The Bleck Family Chair

Tage Larsen

TROMBONES

Timothy Higgins Principal

The Lisa and Paul Wiggin Principal Trombone Chair

Michael Mulcahy

Charles Vernon

BASS TROMBONE

Charles Vernon

TUBA

Gene Pokorny Principal

The Arnold Jacobs Principal Tuba Chair, endowed by Christine Querfeld

* Assistant concertmasters are listed by seniority. ‡ On sabbatical § On leave

The CSO’s music director position is endowed in perpetuity by a generous gift from the Zell Family Foundation. The Louise H. Benton Wagner chair is currently unoccupied.

TIMPANI

David Herbert Principal

The Clinton Family Fund Chair

Vadim Karpinos

Assistant Principal

PERCUSSION

Cynthia Yeh Principal

Patricia Dash

Vadim Karpinos

LIBRARIANS

Justin Vibbard Principal

Carole Keller

Mark Swanson

CSO FELLOWS

Ariel Seunghyun Lee Violin

Jesús Linárez Violin

The Michael and Kathleen Elliott Fellow

Olivia Jakyoung Huh Cello

ORCHESTRA PERSONNEL

John Deverman Director

Anne MacQuarrie

Manager, CSO Auditions and Orchestra Personnel

STAGE TECHNICIANS

Christopher Lewis

Stage Manager

Blair Carlson

Paul Christopher

Chris Grannen

Ryan Hartge

Peter Landry

Joshua Mondie

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra string sections utilize revolving seating. Players behind the first desk (first two desks in the violins) change seats systematically every two weeks and are listed alphabetically. Section percussionists also are listed alphabetically.

Discover more about the musicians, concerts, and generous supporters of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association online, at cso.org.

Find articles and program notes, listen to CSOradio, and watch CSOtv at Experience CSO.

Get involved with our many volunteer and affiliate groups.

Connect with us on social @chicagosymphony

OFFICERS

Mary Louise Gorno Chair

Chester A. Gougis Vice Chair

Steven Shebik Vice Chair

Helen Zell Vice Chair

Renée Metcalf Treasurer

Jeff Alexander President

Kristine Stassen Secretary of the Board

Stacie M. Frank Assistant Treasurer

Dale Hedding Vice President for Development

SENIOR LEADERSHIP

Jeff Alexander President

Cristina Rocca Vice President, Artistic Administration

The Richard and Mary L. Gray Chair

Vanessa Moss Vice President, Orchestra and Building Operations

Stacie Frank Vice President & Chief Financial Officer, Finance and Administration

Ryan Lewis Vice President, Sales and Marketing

Dale Hedding Vice President, Development

For complete listings of our generous supporters, please visit the Richard and Helen Thomas Donor Gallery.