Educational Psychology for Learning and Teaching 7th Edition Sue Duchesne - eBook PDF

https://ebookluna.com/download/educational-psychology-forlearning-and-teaching-ebook-pdf/

(eBook PDF) Numeracy Across the Curriculum: Researchbased strategies for enhancing teaching and learning

https://ebookluna.com/product/ebook-pdf-numeracy-across-thecurriculum-research-based-strategies-for-enhancing-teaching-andlearning/

(eBook PDF) The Skillful Teacher: The Comprehensive Resource for Improving Teaching and Learning 7th Edition

https://ebookluna.com/product/ebook-pdf-the-skillful-teacher-thecomprehensive-resource-for-improving-teaching-and-learning-7thedition/

(eBook PDF) Teaching Strategies for Nurse Educators 3rd Edition

https://ebookluna.com/product/ebook-pdf-teaching-strategies-fornurse-educators-3rd-edition/

Essential Skills for a Medical Teacher: An Introduction to Teaching and Learning in Medicine - eBook PDF

https://ebookluna.com/download/essential-skills-for-a-medicalteacher-an-introduction-to-teaching-and-learning-in-medicineebook-pdf/

consideration of motivation challenges and problems facing educators, then possibilities for addressing these problems and challenges are described. The challenges of reform and standards are introduced in this chapter. Central to problems and possibilities is the issue of motivational equality and inequality.

Part II is composed of four chapters that focus on the socialcognitive processes that influence motivation. Chapter 2 presents the cognitive theory of attribution, the reasons we believe account for our own successes and failures, and those of other people. Attributional theory helps us understand poor performance while offering possibilities for change. It deals with questions such as these: How do one’s beliefs about prior success and failure affect future expectations and actions? How can teachers help students who have given up? The attributional explanation for motivation continues to be one that teachers, parents, coaches, and counselors find especially useful. As one student who had learned about attribution in another class cautioned his classmates, “You will never look at yourself the same way again after learning about attribution.”

Chapter 3 explores the role of beliefs about competence and ability as a motivational factor. Perception of ability is explained from several viewpoints. The first view is self-efficacy, which is the perceived competence about performing a specific task. The strength of our self-efficacy helps determine which tasks we undertake and which ones we persist in. A second view of ability is self-worth, a theory that explains a motive to avoid failure and protect self-worth from a perception of low ability. This perspective can help answer the question: Why don’t students try? A third perspective is that of achievement goal orientation. Students may approach tasks with a goal of improving their ability, proving their ability, or avoiding the perception of low ability. The concluding topic is achievement anxiety, which is especially relevant in view of current emphasis on high-stakes testing.

Goal setting is the subject of Chapter 4. Goals are crucial for achievement, but they are usually given more prominence in athletics and work environments than in academic learning. This chapter deals with the following questions: What are the characteristics of goals that make them effective? How can goal setting be used in educational settings to improve student motivation and learning?

influences student effort and engagement. It includes types of assessment and motivational implications, factors such as effort in determining grades, issues in high-stakes testing and motivation, and a description of an evaluation program to enhance motivation.

Chapter 9, the concluding chapter, focuses on implementation of motivation in the classroom. It begins with discussion of concerns when beginning motivation applications. Next, programs that offer possibilities for improving motivation and achievement are described. This is followed by a problem-solving approach for devising a plan and concludes with ideas where motivation might be used.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank the individuals who contributed their help and support. I am most appreciative of my colleagues Catharine Knight, Susan Colville-Hall, Julia Beyeler, and Rebecca Barrett. The conversations about the understanding and application of motivation knowledge for practice were most valuable. Thanks to Sharon Hall for feedback on specific areas. I am also most appreciative for the continuing support of my department members.

I am grateful for the assistance of Senior Editor Naomi Silverman for her continuous support, encouragement, and insightful suggestions. I am most appreciative to the revision survey reviewers, Kay Camperell of Utah State University and several anonymous respondents, for their thoughtful and helpful feedback.

To my brother Dan I thank you for your continuing support via e-mail and phone and otherwise.

This edition is dedicated to teachers who have the courage to make a difference and to those who have the will to start the journey that makes a difference.

—M. Kay Alderman

PART I SETTING THE STAGE FOR MOTIVATIONAL POSSIBILITIES

part of the chapter presents an overview of the remaining chapters.

MOTIVATION PERSPECTIVES FOR CLASSROOM LEARNING

The criterion for the selection of theory and research included in this text is to identify concepts that provide teachers with the most powerful tools for activation and persistence of their students’ motivation. Tool in this sense means something that is used to perform an operation or that is necessary in the practice of a skill or vocation. As such, motivational tools may take two forms: (a) conceptual understanding (e.g., understand why a student may not try); or (b) the use of tactics (e.g., an appropriate incentive). As you read this text, you can begin building a motivational toolbox (included at chapter ends) that will provide you with strategies to establish a classroom climate that supports optimal motivation and addresses the motivational problems. A form for this is provided in each chapter.

The goal of this text is to make the knowledge applicable and actionable (Argyris & Schon, 1974). Applicable knowledge describes relevant motivation concepts, whereas actionable knowledge shows how to implement motivation strategies in everyday practice. This means that learning a theory and learning a skill should not be viewed as distinct activities. Instead, knowledge must be integrated with action. Take the example of the concept of learned helplessness, a teacher learns to (a) explain this concept, (b) recognize indications of helplessness by students, and (c) select and devise strategies to help the student begin making adaptive responses to failure. The remainder of this section defines motivation and presents the perspective that reflects the content and organization of this text.

Defining Motivation

Conversation is replete with terms that imply motivation, both from motivational theories and from our everyday language. “Sam tries so hard,” “Sarah is just not persistent in her efforts,”

and “There is no incentive for doing a good job at my work” are illustrations of three such motivational terms. But, what is motivation, what kind? Through the years, motivation has frequently been described as having three psychological functions (Ford, 1992): (a) energizing or activating behavior, what gets students engaged in or turned off toward learning (e.g., Mr. Crawford’s math students look forward to the new problem to solve each week); (b) directing behavior, why one course of action is chosen over another (e.g., Maria does her homework before going on the chat room); and (c) regulating persistence of behavior, why students persist toward goals (e.g., although Eddie does not have a scholarship, he continues to run cross-country to be a part of the team). Various motivation perspectives can explain these three functions differently.

The motivation knowledge base that addresses these functions has greatly expanded from grand formal theories (e.g., achievement motivation and social learning) to a broad spectrum of motivational topics (Weiner, 1990). More recently Elliot and Dweck (2005) proposed a theory of achievement motivation with competence as the core. Two current perspectives are need theories and social-cognitive models (Pintrich, 2003). Need theories assume that, as human beings, we are born with basic needs that give direction for motivation. Although two current need theories—self-determination theory (SDT) and self-worth theory— contribute to the understanding of motivation, both integrate social-cognitive constructs with needs. Self-determination is based on the psychological needs for autonomy, relatedness, and competence (Deci & Ryan, 1985). This theory assumes that these needs are basic to human functioning and form the basis for intrinsic motivation. Although intrinsic and extrinsic motivation were previously viewed as either/or, they are now considered as a continuum in the context of self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000) (see Chapter 8). Self-worth theory will be introduced later in this chapter, and then fully explained in Chapter 3.

The focus of this text is predominantly drawn from the socialcognitive theory. Social-cognitive perspectives have been a major focus of recent motivation research especially as it relates to school achievement, the role of teachers, and the beliefs of students as learners (Pintrich, 2003).

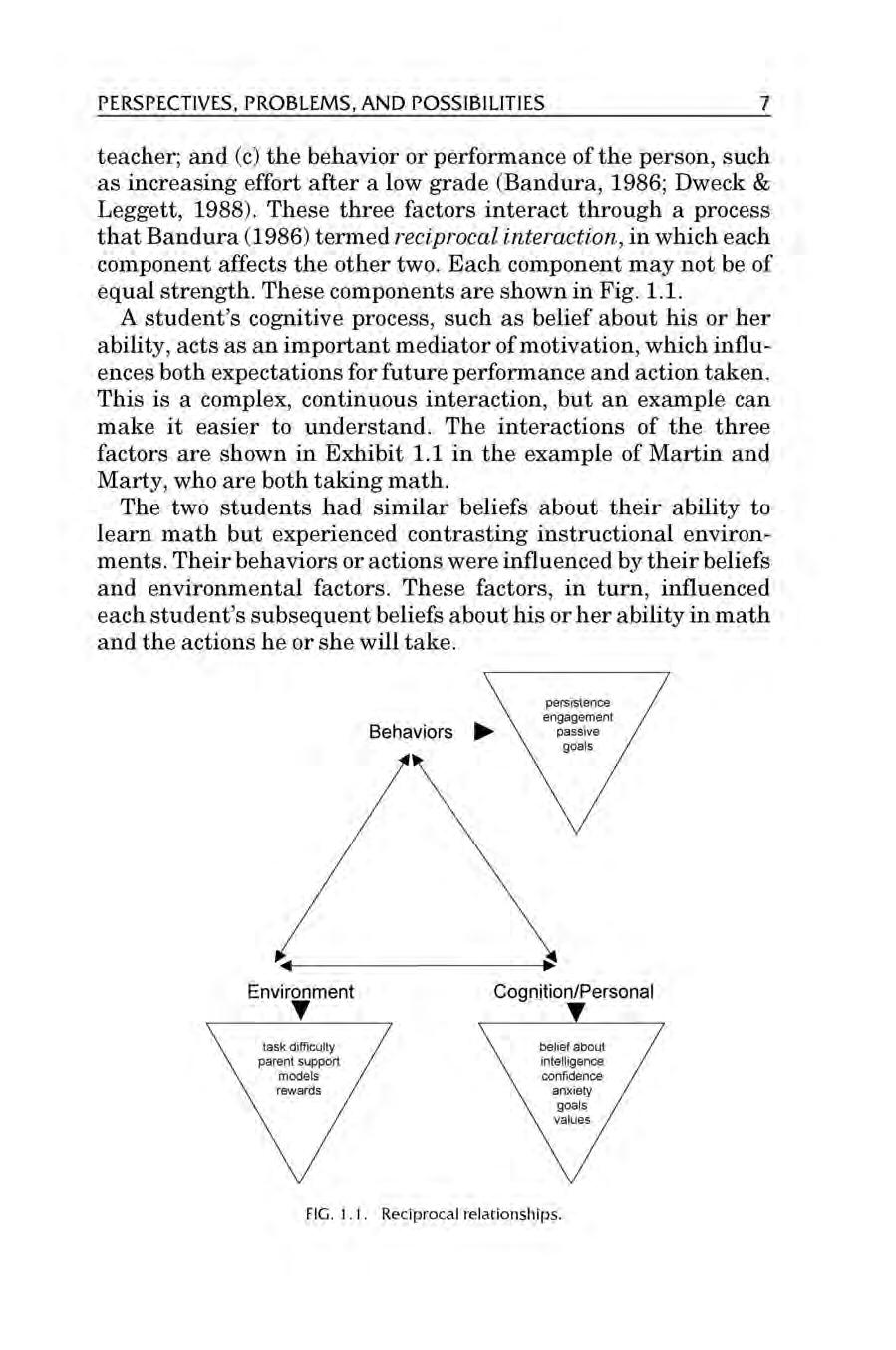

teacher; and (c) the behavior or performance of the person, such as increasing effort after a low grade (Bandura, 1986; Dweck & Leggett, 1988). These three factors interact through a process that Bandura (1986) termed reciprocal interaction, in which each component affects the other two. Each component may not be of equal strength. These components are shown in Fig. 1.1.

A student's cognitive process, such as belief about his or her ability, acts as an important mediator of motivation, which influences both expectations for future performance and action taken. This is a complex, continuous interaction, but an example can make it easier to understand. The interactions of the three factors are shown in Exhibit 1.1 in the example of Martin and Marty, who are both taking math.

The two students had similar beliefs about their ability to learn math but experienced contrasting instructional environments. Their behaviors or actions were influenced by their beliefs and environmental factors. These factors, in turn, influenced each student's subsequent beliefs about his or her ability in math and the actions he or she will take.

FIG. 1.1. Reciprocal relationships.

Exhibit 1.1. A Social-Cognitive Example

Cognition

Both Martin and Marty believe that either you have an ability to learn math or you do not. Furthermore, they believe that if you do not have the ability for math, there is nothing you can do about it.

Environment

Martin is in Ms. Jones’ class. He is placed in the lowest math group. Ms. Jones only gives this group part of the math curriculum. Because she thinks they will not be able to “get it,” she requires little homework completion.

Marty is in Mr. Crawford’s remedial class. This class is structured so the students can develop their math skills. Students must get an A or a B on each test or they fail it. They must retake their failed tests until they pass with a B.

Behaviors

Martin spends less and less time on math. His confusion grows. He develops a dislike for math because the partial curriculum makes math seem very disconnected. His belief about his math ability has been confirmed. He will continue in the lowest math group until he is no longer required to take math.

Marty is surprised at the gradual improvement in her math scores. She chooses to spend more time now on her homework and is thinking about taking more math than planned. Marty is so proud of herself and she should be. Her belief about math ability begins to change.

for their achievement; Ms. Sanders does not believe her students have the ability to do higher order thinking.

Beliefs about Ability. What is the core of the ability problem? In 1976, Covington and Beery wrote what has become a classic description of motivation problems in the schools. The problem, from this perspective, is that “one’s self worth often comes to depend on the ability to achieve competitively . . . to equate accomplishment with human value” (Covington, 1998, p. 78). In our society, the tendency is to equate human value with accomplishment. Many school and classroom experiences then act to undermine an individual’s sense of self-worth because students become convinced that ability is the primary element for achieving success and a lack of ability is the primary reason for failure. The notions about ability are based on comparisons to other students. In competitive situations, the fundamental motivation for many students is to protect their self-worth from the perception that they have low ability. To protect their self-worth, some students adopt strategies to avoid the perception of failure. Two failure-avoiding strategies are setting unrealistic goals (either too high or too low) and withholding effort. Both strategies provide students with reasons other than ability for not succeeding, thus protecting their self-worth. Teachers often characterize these unmotivated students as apathetic or lazy.

Beliefs about Effort. What is the nature of effort as a motivational problem? It is both work habits and beliefs held by students about the relationship between effort and success and failure. This view of effort—characterized by Bempechat (1998) as a “lack of persistence, a preference for easy tasks over challenging tasks, or a tendency to fall apart at the first sign of difficulty” (p. 37)—is detrimental to student achievement. Darling-Hammond and Ifill-Lynch (2006) observed that a frequent refrain heard by teachers is “If I could only get them to do their work!” (p. 8). What is a classroom like when effort is lacking? The academic work problems can be seen in the following description of Ms. Foster’s ninth-grade class.

Ms. Foster says a large number of students are unmotivated. She describes this unmotivated behavior as follows: Many students do not have goals; sit passively in class; turn in no homework; do not keep up

eikä tietänyt koko näytelmästä. — Ketä tuolla navetankatolla on? Ja mitä kojeita niillä on edessään?

— Siellä tervataan kuuta, huusi useampi ääni.

— Tervataan! Kah, onko nyt kuunpimennys, vai mitä se on?

— On. Sitä tehdään parhaillaan, vastasi renki-Matti.

— Tehdään? Kyllä se tekemättä on. Kyllä minä niitä jo monta olen nähnyt näihin päiviin, ei tuo mitään ole.

— Kyllä nähnyt on tässä muutkin, mutta onko isäntä nähnyt tehtävän ennen? kysyi Kujanpään eukko.

— En, eikä muutkaan. Mutta tekevät joutilaat jotakin, sano…

Kun minä kymmenkunta vuotta sitten kävin pappilassa, niin rovasti kun käänteli allakan lehtiä, sanoi: torstaina tulee kuunpimennys illalla, lypsyn aikana, ja niin tulikin juuri. Hän tiesi senkin sanoa, kuinka paljon syrjää jää kirkkaaksi. Ei se mikään merkki ole, tuo. Te olette höperöitä kaikki.

— Mitä se isäntä sanoo? kysyi suutari. Hän oli jättänyt työnsä ja lähtenyt hänkin ulos katsomaan. — Olisiko teidän mielestänne paljon vaikeampi sitä tehdä kuin tietää jo toisena vuonna edeltä, koska se tulee ja kunkamoinen? Sen minä aina olen suurimpana ihmeenä pitänyt, kun siitä olen herraspaikoissa kuullut, sen tarkan edeltä tietämisen. Ja kyllä ne tietävät, herrat. Olen senkin nähnyt, että täsmälleen…

— Mutta semmoisen täytyy olla Jumalan tekoa. Minä puhun teosta enkä tietämisestä.

— Kyllä minä sen ymmärrän. Mutta minä kysyn sentään, mistä tietävät ihmiset tänä vuonna sanoa, mitä Jumala aikoo tehdä tulevana vuonna, ja määrätä päivän ja hetken? Vieläpä laadunkin? Hää?

— En minä tiedä siihen vastata. Mutta sen tiedän, että rovasti sen sanoi ja että se tuli lypsyn…

— Niin, ihmekö se, että tietävät, huusi Kaisa, — kun itse tekevät, herrat.

— Että rovastiko teki? Tuki leukasi, ämmä.

— No ei hän, en suinkaan minä sitä… Mutta mistä sen luki taas? Mustasta kirjastako? Sanotaan…

— Älä siitä huikkaa herrojen aikana, tuhma akka, taikka pian oletkin siinä kirjassa, varoitti Kanervan Jussi.

— Allakasta isäntä sanoi lukeneensa, selitteli suutari. — Se on semmoinen pieni herrojen kirja, kummia merkkejä täynnä, kyllä niitä nähty on. Ja se on tietävinään kaikki edeltä, sateet ja poudat, suojat ja pakkaset. Mutta kyllä se valehteleekin, siitäpä sen tietää, ettei se oikein totuudessa vaeltavien tekoa ole. Ei papit niitä tee… Allakan tekijät ovat semmoisia, jotka lukevat tähdistä, ja ne auringon- ja kuunpimennyksiä tekevät. Kuinka voisivatkaan he niitä edeltä täsmälleen sanoa, koska ne tulevat, jos eivät itse tekisi? Eivätpä he Jumalan ilmojakaan täsmälleen tiedä edeltä.

— No, en minä ymmärrä, mutta…

— Niin nähkääs, isäntä, vaikka minä olen vain renki-Matti, enkä ymmärrä syvältä asioita, niinkuin suutari, niin minäkin voin edeltä

ladonlattialta heinänpölyä, täytti näillä aineilla pussin ja meni sisään.

Tuvassa kirjoitti hän suutarilaudalla paperiliuskalle lyijykynänpätkällä:

En hvit kalf o' en rö', vill di inte lefva så må di dö. [Valkoinen vasikka ja punainen, jos eivät tahdo elää, niin kuolkoot.]

Tämän hän näytti ensiksi tovereilleen, kääräisi kokoon ja pisti sen sitten pussiin pölyn sisälle ja ompeli sen kiinni, jättäen siihen pikilangan päät nauhoiksi. Nyt hän meni takaisin navettaan ja sitoi pussin, jota hän nimitti "elttapussiksi", toisen vasikan kaulaan ja kehotti aamulla varhain muuttamaan sen toisen kaulaan.

Hyvän illallisen emäntä heille laittoi ja samoin he saivat oivallisen yösijan. Aamulla kukon laulaessa kävi emäntä navetassa muuttamassa pussin, ja kun päivä valkeni olivat vasikat terveet. Vieraille laitettiin hyvä suurus ja he saivat vielä kelpo eväät reppuihin. Eikä tarvinnut emännän niitä salaa täyttää, sillä isäntä oli samassa toimessa ja kokosi vielä rahojakin tohtorille ja hänen oppilailleen. Jos nämä eivät itse olisi kieltäytyneet vastaanottamasta, olisi lahjamäärä ollut paljon runsaampikin, sillä nuo hyvät ihmiset pitivät sen suurena menestyksen enteenä, että kuuntervaus tapahtui heillä. Jo vasikkain paraneminen osoitti sitä, heiltä kun oli pitkin vuotta kaikki vasikat kuolleet, sanoi emäntä. Hänelle annettiin neuvo sukia elukat ja sitoa pussi kaulaan. Mutta hauskinta kaikesta oli se, että kaikki olivat jääneet tyytyväiselle mielelle.

Kun nuorukaiset olivat palanneet takaisin Perniöön, niin kirkkoherranrouva täytti Tengströmin evässäkin Jaakko Fredrikin teinirepusta ja pani vielä omiakin varoja lisäksi, sillä hän käsitti että tämän rikaslahjaisen nuorukaisen toveruus oli suureksi hyödyksi hänen pojalleen.

Aamulla, kun Tengström eteisessä seisoi ja vähän alakuloisesti katseli säkkiään, astui rouva samassa ulos keittiöstä. — Mitä seisot ja mietit? kysyi hän.

— Katselen, että säkissäni, johon illalla tyhjensin reppuni, on nyt varmaan Jaakko Fredrikin eväät. Nyt en tunne omiani, mutta tädin avulla ne kai erilleen saadaan.

— Ei siinä hänen ole, ne ovat kaikki sinun.

— Ei, täti kulta, kiitän. Hän oli niin iloinen saaliistaan ja hänestä olisi varmaan kovin ikävä, kun hän ei saisi sitä itse pitää.

— Ei puhuta hänelle mitään. Luuletteko hänen niitä kuukauden päästä muistavan ja tuntevan? Minä täytän hänenkin säkkinsä, ja tämän toimitan heti aittaan ennenkuin hän nousee ylös.

Nuorukainen kiitti sydämellisesti hyvää tätiä. Sitten hän meni ja kertoi Bergelinille saaneensa hyviä uutisia kotiin.

Vielä joulun edellä "oppilaat" saivat lyyran lakkiinsa ja "tohtori" vihittiin papiksi Tukholmassa, jonne kaikki kolme matkustivat avoimella jaalalla. Papiksi vihkiminen tapahtui Tukholmassa siksi, että Turun piispa Kaarle Fredrik Mennander silloin valtiopäiväin aikaan oleskeli siellä.

Tämän pienen kujeilun päähenkilö on, niinkuin arvoisa lukija tietänee, piirtänyt nimensä Suomen historiaan maan ensimmäisenä arkkipiispana. Hänen toveristaan tässä kertoelmassa tuli rovasti ja heidän maisteristaan Merikarvian kirkkoherra.

Mutta teinikepposella oli vielä jälkinäytöksensäkin, jonka lukijan suosiollisella luvalla vielä kerron. Se tapahtui puoli vuosisataa

Arkkipiispa, jonka oli vallannut väsymys, alkoi nousta nojatuolista ja mennä levolle, koska nyt tuntui siltä, että kukaties saisi rauhassa nukkua. Mutta silloin virahti mieleen ajatus: mitä se eukko minun kaulaani siveli ja niskaani hypisteli ja puheli sitä ja tätä sitä tehdessään? Paniko se sinne jotain?

Hän koetteli yömekon päältä niskasta. Ei siellä tuntunut mitään.

Mutta sittenkin…

Hän koetti sormellaan mekon alta yöpaidan kauluksen päältä. Ja oikein, siellä tuntui solmu, josta lähti nauhat.

— Mitä tämä on? sanoo hän ja vetää nauhoista, jotka aukenevat ja johtuvat hänen poveensa yömekon alle. Sieltä hän vetää esiin kummallisen esineen. Se oli pieni kulunut, pitämisestä mustunut kiiltävä nahkapussi, jonka yläreunaan näkyi uudet puhtaat valkoiset nauhat ommellun.

— Mitä…? Onko ihminen hupsu? sanoi hänen kunnianarvoisuutensa suuttuneena. — Aiotaanko minua taikakeinoilla parantaa? Katsotaanhan kumminkin ensin mitä siinä on, mutta kyllä sitten saavat kuulla!

Hän otti kynäveitsen ja paperiarkin, laski pussin pöydälle paperille ja viilsi sen siinä halki.

— Ei mitään muuta kuin pölyä, joku heinänkorsi ja karvoja, valkoisia ja ruskeita, mitä moskaa…! Hyi! Ja nämä sitten ovat parannusaineita. Voi sitä taikauskoa! Mitä tuolla sisempänä on? Paperia. Siellä nyt on taikasanat, joku loitsu. Eivätkä Halikon papit ollenkaan tiedä, mitä heidän seurakunnassaan piilee. Mutta minäpä

teenkin nyt heille pitkän nenän ja otan tiedon tämän taikakalun

tekijästä, sillä eukon täytyy se ilmoittaa! Ja sitten panenkin hänet lujalle. Mitä tuohon on töherretty? Täytyy etsiä silmälasit ja sytyttää toinen kynttilä.

Se oli pian tehty. Hän istui jo lasit nenällä ja katseli kirjoitusta, joka kuluneena ja äkkiä pyöräytettynä kumminkin näytti tutulta. Hän luki vähän vaikeasti: — Enhvitkalfo'enrö',villdiintelefvasåmådidö.

Nyt aukesi hänelle äkisti menneiden päivien muisto. Hän tunsi omat kirjaimensa siinä. Ja sydämellinen, iloinen nauru kaikui hänen huuliltaan. Hän eli äkkiä uudestaan kaikki ja nauroi kuin koulupoika.

Nauru kuului toisiinkin huoneisiin. Kiireesti tulivat arkkipiispatar ja muori sisään. He olivat lähtiessä huoneessa hiljaa odotelleet, että hän menisi maata ja saisi yölevon.

— Herrajesta, kuinka nyt on asiat? huudahti muori, joka näki rikkileikatun pussin pöydällä ja arkkipiispan istuvan nauraen paperiliuska kädessä. — Mitä te nyt olette tehnyt, semmoisen vahingon! Oi voi!

Piispa nauroi yhä hullummin, ihan huone kaikui.

Mutta nyt suuttui eukko. — Ei sitä niin tarvitse nauraa, sanoi hän kiivaasti. — Sillä on monta tautia parannettu ihmisistä ja elukoista.

Piispa sai naurultaan vaivoin puhutuksi. — Mistä te, muori hyvä, olette tuon ihmeellisen taikapussin saanut? Tiedättekö kuka sen on tehnyt? Ja kuka tämän paperiliuskan siihen on kirjoittanut sekä mitä se sisältää?