play outside the perfect place to

Miles of hiking, biking, and water trails are waiting to be explored in Berkeley County, West Virginia. Two Audubon Society managed preserves are the perfect locations for bird watchers to spend the day. Serene fishing spots, championship golf, and world-class geocaching make for the perfect adventure vacation.

For generations, Appalachian forests have provided for families, shaped communities, and stood as a testament to resilience.

The Family Forest Carbon Program helps landowners like you continue that legacy—offering financial support and expert guidance to improve forest health while keeping your land in your hands.

Put your mark on the land, keep it healthy, and get rewarded for responsible stewardship.

Now enrolling landowners up and down the Appalachian range.

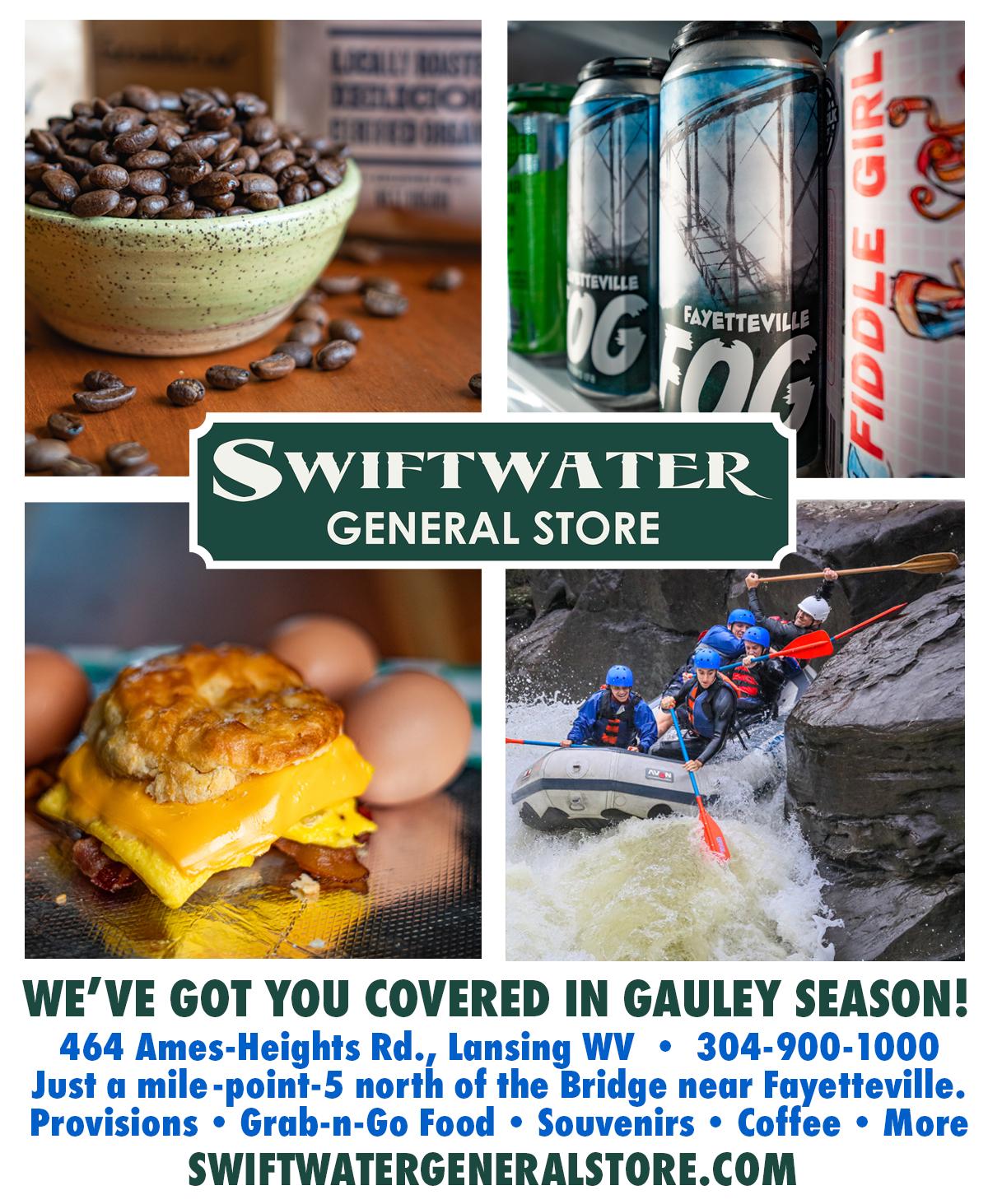

THIS FALL, CONQUER THE WORLD-CLASS RAPIDS OF THE GAULEY RIVER.

Running only seven weekends in September and October, Gauley season is a short-lived thrill for true whitewater adventurers.

Start planning your rafting trip to the New River Gorge.

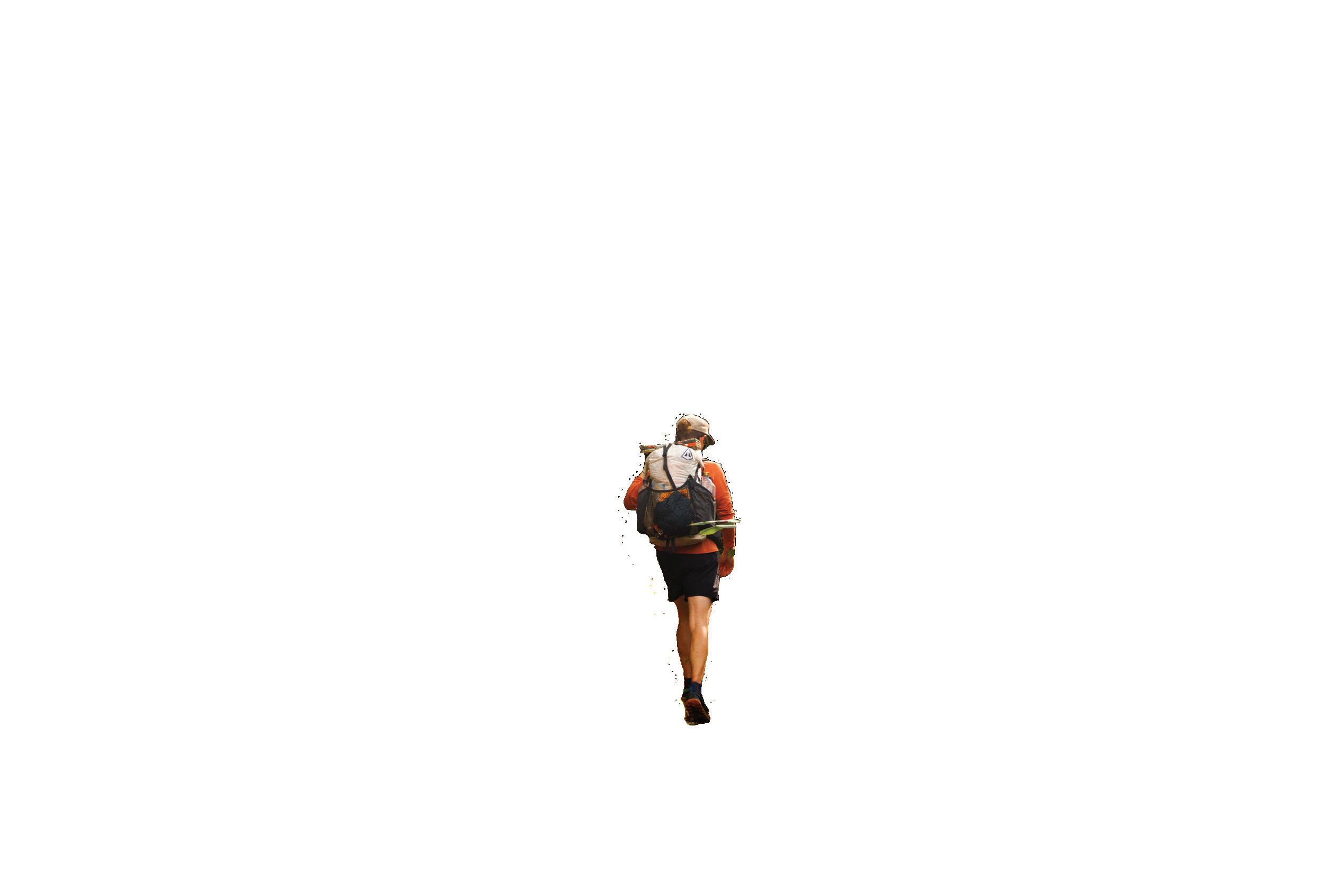

Test your endurance on West Virginia’s longest trail — the Allegheny Trail — and conquer the backcountry routes in Pocahontas County. But when you’re ready for the rest, discover colorful mountain drives, quiet sunrises and peaceful campgrounds. Come to roam, stay for the rest.

FROM THE EDITOR

A few years ago, my aunt gifted me a book called The Forest Unseen . The basic premise is the author picks a one-square-meter plot in an old-growth forest near his house in Tennessee and visits it nearly every day for a year. He spends hours upon hours sitting at that one spot, whether in the deep cold of winter or the blazing heat of summer, observing the small creatures that reside there, from ferns and moss to snails and salamanders. Through this process, he pays close attention to not only the smaller forms of life, but also the larger processes that shape the forest, such as wind and light.

STAFF

Editor-in-Chief, Co-Publisher

Dylan Jones

Co-Publisher, Designer Nikki Forrester

Copy Editor Amanda Larch Hinchman

Happy Fall Y'all

Dylan Jones, Nikki Forrester

CONTRIBUTORS

Mark Bias, Nikki Forrester, Matthew Grahovac, Rosalie Haizlett, David Johnston, Dylan Jones, Karen Lane, Braiden Maddox, Nathaniel Peck, Adam Polinski, Brett Rothmeyer, Amanda Smith, Jesse Thornton, Chris Wade, Jay Young

The past few months have been tough for me in my home of Tucker County. I’ve taken on a full-time volunteer position fighting the construction of a gas- and diesel-fired power plant that will pollute our air, slurp up our water, and contaminate the rivers and streams we all love. Suffice it to say, it can be hard to find hope right now.

Since February, I’ve walked roughly the same route through the woods behind my house. I’ve watched as the snow melted and gave way to budding trout lilies. I’ve seen the trout lilies die back and make room for fuzzy fiddleheads. During the deep green of summer, I’ve brushed past ferns that rise far above my head. Now those ferns are turning brown. Wind rustles through yellowing maple leaves in the canopy as I listen to the sound of a lone crow’s wings flapping overhead. It’s cool and crisp and I feel winter approaching. I’m eager for a blanket of fresh snow under a calm, clear night.

In a world that feels frenetic, manic, and full of choices, it’s comforting to return to the same spots over and over again. On my daily walks, I linger at a memorial for a dear

friend who passed away before visiting the neighborhood bog, now full of cottongrass and gentians. While I struggle to sit in a single place for longer than five minutes, walking along a familiar path gives me a chance to slow down, take a deep breath, and remind myself that one day I’ll be gone and, hopefully, this forest will live on.

Exactly 100 years ago, the Civilian Conservation Corps planted the spruce trees that now tower above me. At the time, there was no way of knowing what that forest would ultimately become. They likely wouldn’t see the trout lilies carpet the forest floor or the fields of ferns or the juncos happily flitting about. At the time, they were simply planting seeds for a future better than their own.

After all, all we can do is the best we can with the little time we have. I take comfort in knowing I’m just a speck in the grand arc of time. There will still be trees, flowers, birds, mushrooms, moss, salamanders, and ferns. So, I’ll savor every step through the sun-dappled forest. I’ll pay attention to every leaf and petal, staying tuned to buzzing bees and dancing damselflies. And when the time comes, as it inevitably does, I’ll stand up to protect these wild, precious places that don’t have the words to stand up for themselves. Because while we will certainly be outlived by something, what we have now is pretty amazing. w

Nikki Forrester

SUBSCRIPTIONS

Get every issue of Highland Outdoors mailed straight to your door or buy a gift subscription for a friend. Sign up at highland-outdoors.com/store/

ADVERTISING

Request a media kit or send inquiries to info@highland-outdoors.com

SUBMISSIONS

Please send pitches and photos to dylan@highland-outdoors.com

EDITORIAL POLICY

Our editorial content is not influenced by advertisers.

SUSTAINABILITY

Highland Outdoors is printed on ecofriendy paper and is a carbon-neutral business certifed by Aclymate. Please consider passing this issue along or recycling it when you’re done.

DISCLAIMER

Outdoor activities are inherently risky. Highland Outdoors will not be held responsible for your decision to play outdoors.

COVER

A rare display of the aurora borealis delighted skywatchers across the Mountain State in October of 2024, seen here from Bear Rocks Preserve in Dolly Sods. Photo by Matthew Grahovac.

Copyright © 2025 by Highland Outdoors. All rights reserved.

Nikki Forrester

John Herod finds a little booter off a rock slab in early fall, pg.

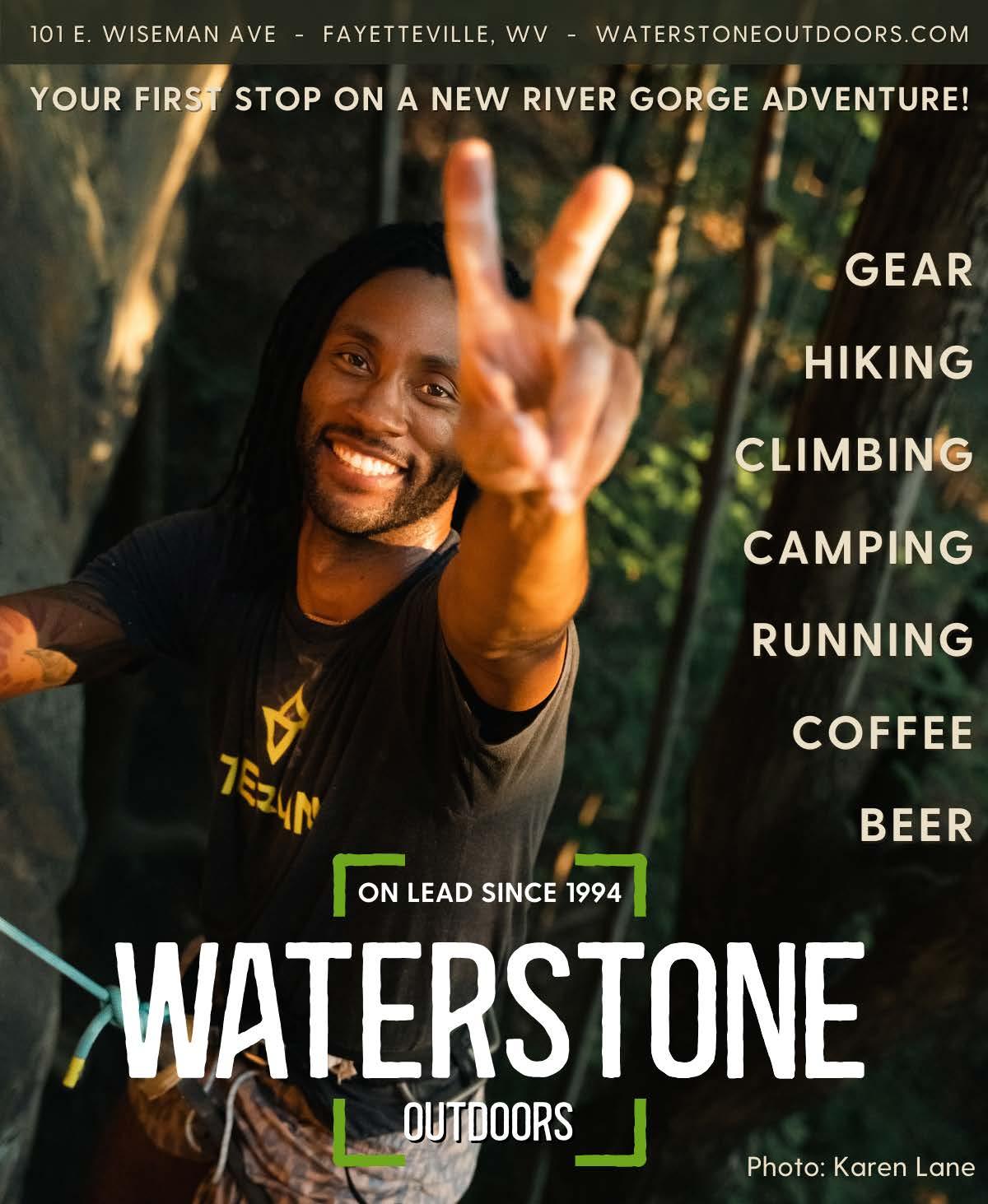

GATEWAY TO SANDSTONIA PROTECTS ROCK CLIMBING ACCESS IN THE NEW RIVER GORGE

By HO staff

Climbers, rejoice! Access to the Sandstonia crags along the north rim of the New River Gorge has been permanently protected thanks to a partnership between the West Virginia Land Trust (WVLT) and the New River Alliance of Climbers (NRAC). The 40-acre Gateway To Sandstonia Preserve, which is open to the public, features a new climbing access trail and parking lot so visitors can continue exploring these beloved cliffs.

Located minutes from downtown Fayetteville and just across the iconic New River Gorge Bridge, the crags of the Sandstonia area have been popular among rock climbers of all skill levels for some 40 years. “The first time we were told that this property was coming to us, we were excited,” said WVLT preserve steward Shannon Gillen. “We were looking forward to assisting the climbing community by providing them with trails that are welcoming and comfortable to walk on and a publicly accessible parking lot.”

The preserve will eventually offer three miles of new hiking trails, an informational kiosk, and a pavilion. While the primary focus of the project was to protect and ensure access to the multitude of climbing routes within the bounds of the New River Gorge National Park and Preserve, the new trails will be open to hikers and birders who can enjoy the diverse hardwood forests and epic views along the rim of the gorge. “There’s going to be a lot packed into a small space,” Gillen said.

Those familiar with Sandstonia will undoubtedly recall the old approach to

Correction (Oops!)

the crags, which had climbers hoofing it up and down steep, eroded hills under a power transmission line. “It wasn’t the ideal scenario,” Gillen said. The new approach trail will keep climbers in the serene shade of the forests, away from the power line cut, and lead them directly to the crags.

The Good Luck Cemetery, which is privately owned, used to serve as the de facto parking area for Sandstonia, but increased visitation over the years led to that private lot being closed to the public. “With the new lot in place, people are welcome to continue accessing and using the area,” Gillen said.

The new parking area on Ames Heights Road, which was constructed by the stoked folks at NRAC, is open for public use. NRAC is a longstanding advocate for climbing access around the New River Gorge region,

highly regarded for keeping climbing routes safe with hardware replacements and for throwing epic fundraising events. “NRAC has been great to work with; they’ve been so patient as we’ve gone through the legal processes of acquiring land and dealing with deed restrictions,” Gillen said.

“Partnerships are always unique for us, but working with a climbing-based recreation group was especially unique,” Gillen said. The WVLT will retain ownership of the tract, keeping this crucial access point preserved in perpetuity. “It’s also the first time we’re [owning land] directly bordering the National Park Service. I think the park service is thankful that a conservation-minded entity borders the park and has plans they’re happy about.” w

To support this ongoing project or learn more about the WVLT and NRAC, visit www. wvlandtrust.org/sandstonia. Climb on!

Lovers of rectification, rejoice! For we are here to highlight our past mistakes, issue a few corrections, and learn from said mistakes as we plow forward into the unknown. In our Summer 2025 issue, we made a whoopsie when we incorrectly credited the image on page 49 to Robert Bird. The actual photographer is Roger Bird, and even though he told us not to worry about it, we couldn’t sleep at night knowing that our error might remain out in the inky ether for the remainder of time. Apologies, Roger! Additionally, we flip-flopped the captions on page 51 for the two photos on page 50. The top image was snapped by our own Dylan Jones, and the bottom image by our homie Chris Jackson. And that, folks, is why you never run your design edit of the magazine the day it’s due.

Courtesy West Virginia Land Trust

WEST VIRGINIA IS NO FUN :(

By HO-HUM Staff

Or so say the city slickers who run WalletHub, a personal finance website based in Miami, Florida. According to WalletHub’s list of Most Fun States in America (2025), there is no fun to be had in West Virginia. The Mountain State ranked 50th based on an assessment of two categories: Entertainment and Recreation, and Nightlife. Interestingly, Florida ranked second—bias, anyone?

Let’s kick things off with Entertainment and Recreation. Sure, we don’t have the greatest number of attractions, if you define attractions as restaurants, amusement parks, movie theaters, fitness centers, beaches, and marinas (which they did), but we’ll take a sandy beach on a mountain river (with zero sharks) over a packed Florida beach any day. And restaurants? We’re all about quality over quantity these days, and Appalachia’s got more fivestar potlucks than you can shake a ladle at. Why wait for a table and shell out a hundred bucks for a meal when you can gather with all your friends and eat till you drop?

As far as nightlife goes, while we definitively do not have the raucous all-night dance clubs that dot Miami Beach, we’ve got the original nighttime social gathering down pat: the campfire. We could argue over the merits of four-on-the-floor techno versus yet another rendition of “Wagon Wheel” until we’re blue in the face, but a campfire out in the Monongahela National Forest with a bottle of whiskey is certainly cheaper than a DJ and bottle service in da club. Although you won’t see nearly as many celebrities in our hills and hollers, you’ll see way more stars because, unlike Miami, we can actually see the Milky Way here.

Let it be known that we’ve never been so proud to come in last place. They say it’s lonely at the top, but those high-ranking “fun states” sure seem way more crowded. What we lack in modern trappings we more than make up for with mountain living. At the end of the day, West Virginia certainly isn’t for everybody, but it’s got the right amount of weird for weirdos like us. Or, as our rad buddy Robby says, “You probably wouldn’t like it.” w

Disclaimer: We used a heavy dose of satire in the creation of this brief. Here at Highland Outdoors, we strive to be inclusive and recognize that every state has its merits, even Florida.

Top:

Dylan Jones.

Bottom: Jay Young

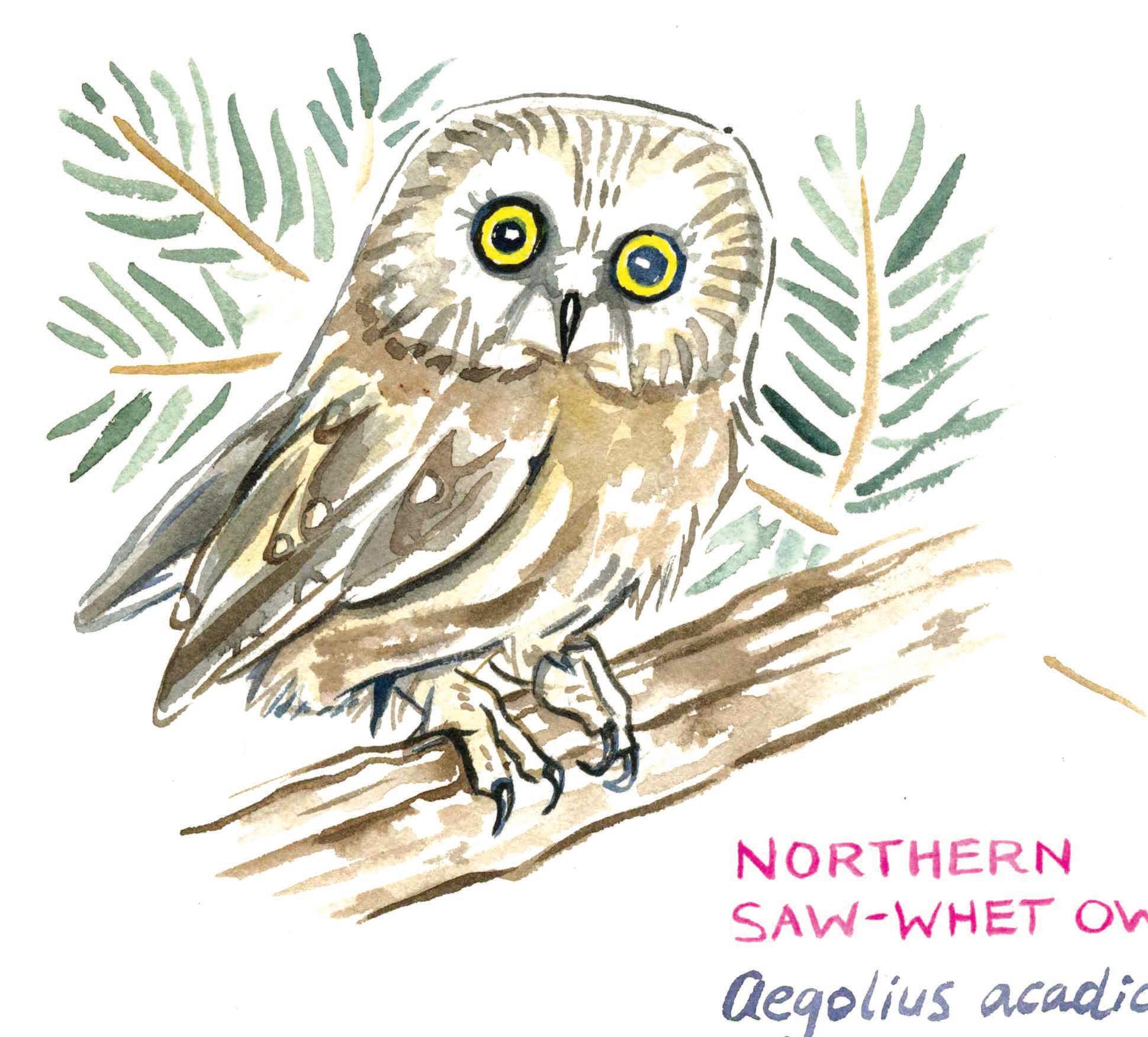

t’s early evening when I arrive at the Canaan Valley National Wildlife Refuge. I knock on the door of a tiny trailer and am welcomed into the warm glow of a bird-banding station. Tonight, I get to observe the bird-banding process for northern saw-whet owls, the smallest owl in eastern North America and one of the cutest animals I’ve ever seen. If the migration winds blow in our favor this evening, I’ll get to see my first wild saw-whet owl in person.

We bundle up to keep warm in the crisp October air and head down a narrow footpath into a dense stand of red spruce trees, a habitat frequently associated with saw-whets since they need the thick tree cover for roosting. We unfurl several 12-meter-long mistnets (which are called this because the

mesh is so fine that it resembles a light mist) and position them in an elaborate maze. Next, we unpack a radio and speaker system and begin to play high-pitched breeding saw-whet owl sounds—a rhythmic “toot toot toot toot”—to attract the birds into our nets. Then, it’s a waiting game.

We take the trail back to the trailer, pausing to admire the Milky Way as it casts its hazy glow above the sleepy fields of Canaan. With thermoses of hot tea in hand, I take this opportunity to chat with the folks who’ve dedicated their evening—and much of their lives—to bird conservation. LeJay Graffious established the station at this location in 2022 and serves as its coordinator. He wasn’t trained as an ornithologist, but he developed an interest in birds back in the 1970s as a young school teacher when he was invited on a bird-band ing expedition.

“I learned that each species has its own song—a revelation that transformed me into a serious birder and set me on a path of sonic sleuthing in the field,” he says. LeJay went on to train under master bird banders and even tually become one himself. Now a retired school principal, he co-directs the Allegheny Front Migra tion Observatory in the Dolly Sods Wilderness and runs this station in Canaan Valley with permission from the refuge.

Since the early 1900s, bird banding has been a crucial way for scientists to track the migration, lifespan, and overall health of bird populations. It involves capturing individual birds and making note of their sex, weight, wingspan, age, location, and sometimes taking blood samples. Then, each bird is given a small metal band to wear around their ankle that features a unique identification number. All of this data is submitted to the United States Geological Survey to create an in-depth picture of the overall health of different bird species. While electronic tracking devices have come onto the scene and replaced bird-banding in some scenarios, traditional banding is still important for saw-whet owl research for a variety of reasons, including their nocturnal and nomadic behaviors that make them difficult to track using other methods.

Cheyenne Carter assists LeJay nearly every evening of fall migration, making the winding two-hour trek from Morgan-

was so impacted by this experience that she sought out every opportunity she could in the following years to learn about birds. She helped with bluebird trail projects, Christmas bird counts, songbird and owl banding, and eventually earned a degree in biology with a focus on wildlife. “It’s such an honor to work and learn from someone like LeJay who has so much experience with birds and who wants to teach me,” she says. “I try to soak up as much as I can, even if it means sleepless nights.”

Before I know it, our 45-minute timer is buzzing and it’s time to venture out again to check the nets. We approach and scan for sound or movement, and sure enough, we have our first visitor. Cheyenne gently unwraps the bird from the net and places her in a small sack to transport back to the trailer. When I get a closer look, it’s hard to believe that this critter is real; she’s like a real-life furby! I’ve only met a few wild animals that were so adorable they truly resembled children’s toys—spotted salamanders and puffins among them—but this little owl takes the cake. She stands at a slight seven inches tall, roughly the size of a robin. The bird takes in her surroundings with bright yellow, doll-like eyes that blink slowly underneath long lashes.

The team gathers all the necessary measurements and data, then turns out the lights to shine a blacklight at the bird’s extended wing to see which feathers glow. This helps

us understand the owl’s age, since new feathers contain large quantities of pigments called porphyrins that cause feathers to fluoresce under black light, while older feathers don’t glow as much. We determine that this saw-whet is a hatch-year owl since her feathers are bright pink under the ultraviolet light. Once LeJay and Cheyenne record all the information they need, we take the owl outside and set her on a fence post. She looks around for a while as she reorients, then soundlessly zooms straight up in the air like a

Back in Canaan Valley, we repeat this process again and again throughout the night: waiting, checking nets, documenting each bird, and then releasing them. I learn the furthest-flung owl that’s been recaptured at this station had been previously banded in Tadoussac, Quebec, nearly 1,000 miles from here! Not all saw-whets migrate though, and this station sometimes sees resident birds who make the refuge of Canaan their year-round home.

I like to think of migratory birds as postcards from afar, flying in for a short time and carrying with them a piece of the other worlds they’ve seen. Some of these little saw-whets have glimpsed the vast forests of French-speaking Québec, cruised above the granite peaks of the White Mountains, stopped to rest in the Ridge-and-Valley range of Central Pennsylvania, and are now hunkering down in the spruce thickets of Canaan. I’m glad they’ve chosen to pay us a visit, and I’m hopeful that our forests can continue to provide a refuge for these delightful bundles of fluff long into the future. w

Rosalie Haizlett lives in Elkins and is the author of Watercolor in Nature and Tiny Worlds of the Appalachian Mountains. This series is part of her art-science fellowship with Creature Conserve.

Owl wing under blacklight

MOUNTAIN STATE MONSTERS

Words by Dylan Jones

Photo illustrations by Jay Young

Many are familiar with West Virginia’s famed cryptids. From Mothman and Batboy to Sheepfoot and Braxxie, aka the Flatwoods monster, these folklore legends have exploded in popularity among contemporary Appalachian culture. One toymaker even sells Lego-style kits where kids (and adults, duh) can build these classic creatures.

Jay Young, a photographer and videographer based in Fayetteville, has long been enamored with the Mountain State’s monster myths. As a visual designer, he often lets his imagination run wild and started thinking about what else might be out there lurking in the misty hollers, murky waters, and dark woods that characterize the creepy aspects of our state’s wild places.

It all began a few years ago while he was driving across the New River Gorge Bridge early in the morning on his way to work. There’s often an impenetrable sea of fog filling the gorge before the sun burns it off; sometimes the fog laps against and over the bridge deck like ocean waves. “I started imagining a giant whale breaching out of the fog,” Young says.

One morning, he stopped at an overlook and snapped a photo of the foggy gorge, then went home that evening and found a stock image of a whale online. “I kind of painstakingly photoshopped it in there, not really knowing what I was doing,” he says. “If you zoom in on the high-res file, you’d see

all kinds of errors. But I posted it on Facebook, and people ate it up, they loved it.”

Young immediately knew he was on to something. He got an aerial shot of the foggy gorge, but this time he added a giant 1950s-style robot emerging from the fog, adding fire and lightning bolts to up the cheese factor. “I had even more fun with that one, and it just took off from there,” Young says. “All of a sudden, I had this idea to do a “Monsters of the New River Gorge” calendar and set off on the quest to create twelve unique monsters.”

Young mostly uses his original photographs for each creation and photoshops in all sorts of elements, like the monsters, visual effects, lighting, and color changes. “I obviously didn’t take a picture of a kraken at the foot of the Summersville Dam, but I did take the original photo of the dam,” he says.

At first, he scoured his archive to find existing photos where he could add monsters. As the project progressed, he started coming up with concepts and would go out to shoot photos with a specific monster in mind. For Young, it’s mostly about having fun, although he does strive to achieve the element of realism with his imaginative creations. “I want the end result to look like it’s an actual photo of this actual thing, and I think I’ve achieved that with varying levels of success,” he says.

Bridge Day is West Virginia’s biggest one-day festival, with nearly 100,000 people attending each year to watch BASE jumpers huck themselves off the country’s third-highest bridge. While jumping off a thousand-foot-high bridge into a gorge with only a parachute to slow your descent would be considered exhilarating by most, imagine doing it while a giant archaeopteryx swoops down to try and gobble you up. “I knew I had to have a Bridge Day image in there, and first I had the idea of a giant frog in the river below with its mouth open, but wasn’t able to find the frog image I needed. I was browsing pterodactyl images and found this archaeopteryx, and it had the same lighting as the bridge in my image,” Young says.

Remember the spooky scene in Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers when Frodo locks eyes with the deceased Elf in the Dead Marshes and falls into the water, only to be dragged down into the murky depths by decrepit ghouls? Well, now you can think of that every time you fall out of your raft! But instead of the tortured ghosts of Elves, you’ll be escaping the cold grip of zombie mermaids, which seem to be a new species of monster endemic to the New River.

“I was originally thinking of a sunken pirate ship, but the scale of the photo wasn’t working for anything like that, so I thought what about scary mermaids,” Young says.

‡Located in the bucolic setting of Pocahontas County, the Green Bank Observatory is the world’s largest steerable radio telescope and has been an instrumental part of the search for intelligent extraterrestrial life. Welp, it looks like that search was successful, because contact was made, and it turns out that aliens really love hamburgers. Beef me up, Scotty!

“This is one of my favorites, even though I don’t think it looks horribly realistic,” Young says. “Finding a whole bunch of stock photos of cows in weird positions was definitely the hardest part of this one. When I found that stock image of that cow with that look on its face, it was perfect. That cow is totally thinking, Are you kidding me?”

When the Gauley River was dammed in 1966, the town of Gad was flooded as the lake rose. The convention at the time was to name the dam after the nearest town, but “Gad Dam” didn’t sit too well with the powers that be, and thus the barrier was named the Summersville Dam. The pool at the foot of the dam is familiar to folks putting on to run the Upper Gauley during the fall paddling season. But when this giant cetacean rose from the depths, it’s safe to assume someone shouted, “Look at that Gad Dam kraken!”

“The pool below the dam is kind of eerie to begin with, it’s such a weird landscape to see, especially in the morning with the fog there,” Young says. “You can totally imagine something in there, and I think this kraken is one of the most realistic looking monsters.”

Thalassophobia is the intense fear of deep bodies of water—especially when dark and murky—and whatever might be lurking under the surface. West Virginia has plenty of mountain rivers with deep pools, dark water, and submerged boulders that could be hiding whatever your mind can conjure. If you weren’t scared of water before, this shot of gargantuan koi heading toward two kayakers on the New River might instill some thalassophobia deep in your brainstem.

“This one was easy to create because there are a lot of stock photos of koi in water, and all you gotta do is make the water look like river water,” Young says. “The ripples were a little trickier as each set was a different image I had to incorporate.”

Perhaps the most famous of West Virginia’s cryptids, the Mothman is associated with Point Pleasant and the deadly Silver Bridge collapse of 1967. Fortunately, the bridge was rebuilt and still stands today despite the Mothman making another nighttime appearance.

“I went to Point Pleasant specifically to get this photo. It was actually taken in raw daylight, but I darkened the photo and added in the night sky.” Young says. “I bought a mothman figurine and hung it with fishing line off my deck, created the lighting conditions I wanted, and took a photo of it to add in.” w

Jay Young is a photographer and videographer who lives in Fayetteville with his wife and two kids. Check out his full Monsters of WV calendar: ironarchphoto.com/monsters-of-wv-1.

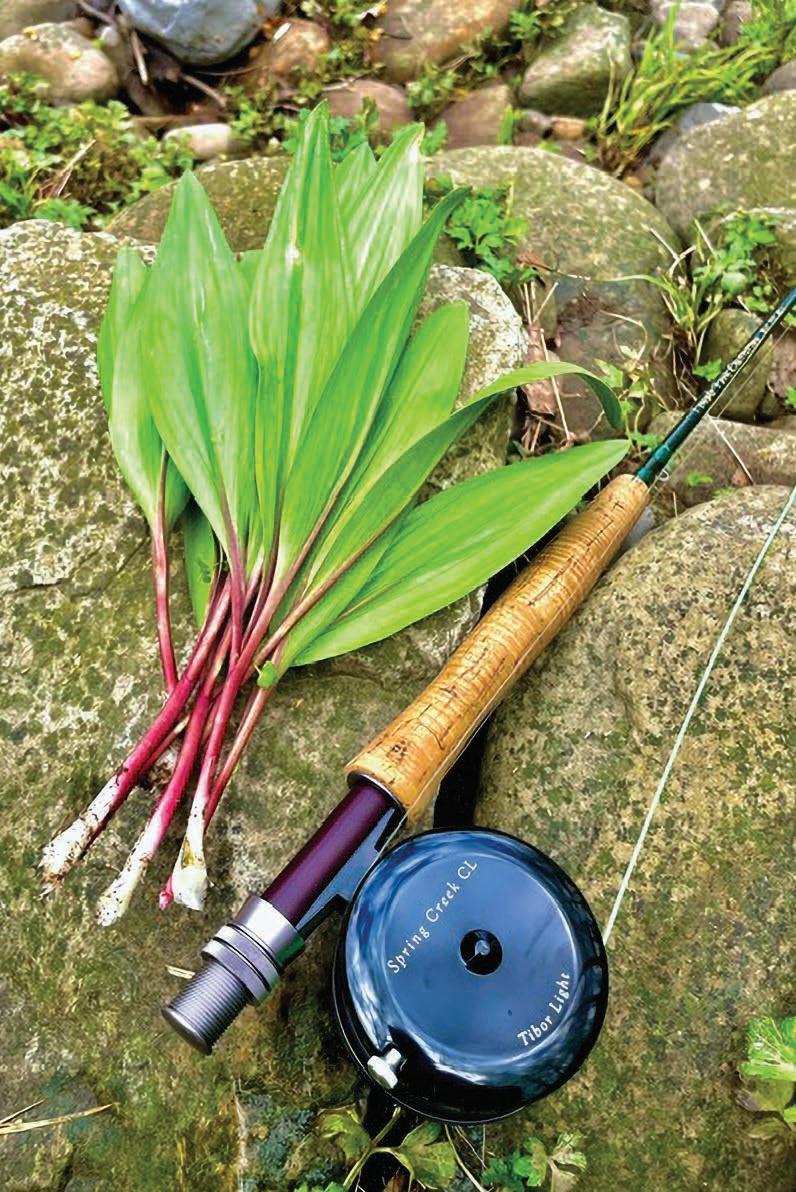

LIFE ON THE FLY

By Chris Wade

Igrew up in Fairmont, West Virginia, downstream from Valley Falls where the Tygart Valley River winds its way through Colfax before it meets the West Fork to form the Monongahela. It was there in Colfax, along a sweeping bend of the Tygart, where I first learned how to cast a fly rod.

Although I mostly fished for smallmouth bass, I became proficient in catching the occasional sycamore branch. On summer evenings, with the familiar sounds of cicadas buzzing and birds chirping filling the humid air, I stood in the knee-deep water casting a popper fly, freshly tied by my dad, into a channel where the smallmouth fed. This was my introduction to what has become a lifelong passion, one that’s introduced me to some of my closest friends.

Fly fishing requires patience, practice, and an understanding of timing—both in terms of casting mechanics and the cycles of the natural world. It has taken me to some very remote and peaceful locations and given me a deep appreciation of pristine places. Reading a stream, searching for aquatic life, and finding that perfect drift—placing the fly so it moves naturally with the water current—make every adventure on the water a learning experience.

Learning how to roll cast on small native streams makes for a learning curve as steep as the terrain these waterways tumble down. Having hooked my fair share of the prevalent West Virginia maple, oak, or rhododendron trout, this is something I often attest to. Improving your fly casting involves constant evolution and

Dylan Jones

adjustment. Landing the perfect drift gives me the same satisfactory rush I imagine paddlers experience when navigating the perfect line through raging rapids.

During a recent outing with Darell Hensley, a good friend and local guide, he asked to observe my line management then immediately offered sage advice on mending. The impromptu lesson goes to show that even after decades on the water, I’m still learning. Darell is a fishing expert on the waterways throughout the West Virginia highlands who owned and operated the Tory Mountain Outfitters fly shop in Davis from 1997 to 2003.

I was a young kid when I first met the legendary Dr. Frank “Doc” Oliverio, who owned the Evergreen Fly Fishing shop in Clarksburg. My dad and his fishing buddies would take fly-tying classes and mill about the shop for hours while telling tales of past adventures. Doc occasionally took me under his wing and guided me on the stream during a day out with my dad and his friends. Looking back, walking and reading the rivers and streams with Doc taught me many of the techniques I still use today. I think he enjoyed teaching as much as he did fishing; that generational sharing of knowledge is something I enjoy as well.

Over the years, I’ve explored beyond the Tygart, venturing into the highlands of Tucker County and wading through the rolling waters of Randolph, Pendleton, and Grant counties. The small trout streams that lace through Canaan Valley and the Seneca Creek Backcountry are some of the most pristine waters I’ve fished. Standing in the Cheat River watershed on the west side of the Eastern Continental Divide, those headwaters eventually flow into the Gulf of Mexico. On the east side, your drifts could end up in the Chesapeake Bay.

My brothers and I would do an annual father-son weekend on the Cranberry River and bike upriver to camp where Dogway Fork enters the Cranberry. The crystal-clear water of the catch-andrelease section has always been ideal to look for rising rainbow, brown, and brook trout, the latter of which is, of course, West Virginia’s official state fish (although technically a member of the char family).

One evening while walking back to camp from the stream, I caught a black bear digging through my food storage that I had just unpacked for the night’s dinner. I immediately ran upstream a couple hundred yards where my dad was fishing and told him about the bear pillaging my ramen noodles. The next thing I remember was my dad running full charge with branches in hand to chase off the curious bear. Later that evening, a nearby solo camper came over to our fire to ask if he could move his tent a little closer. The hungry bear continued watching us from across the river late into the night. It’s deep in remote places like the Cranberry, Potomac, and Cheat watersheds that you can spend entire days fly fishing without seeing another person yet encountering plenty of wildlife.

These streams and rivers, however, have not always been as healthy as they are today. Decades of acid mine drainage, silt

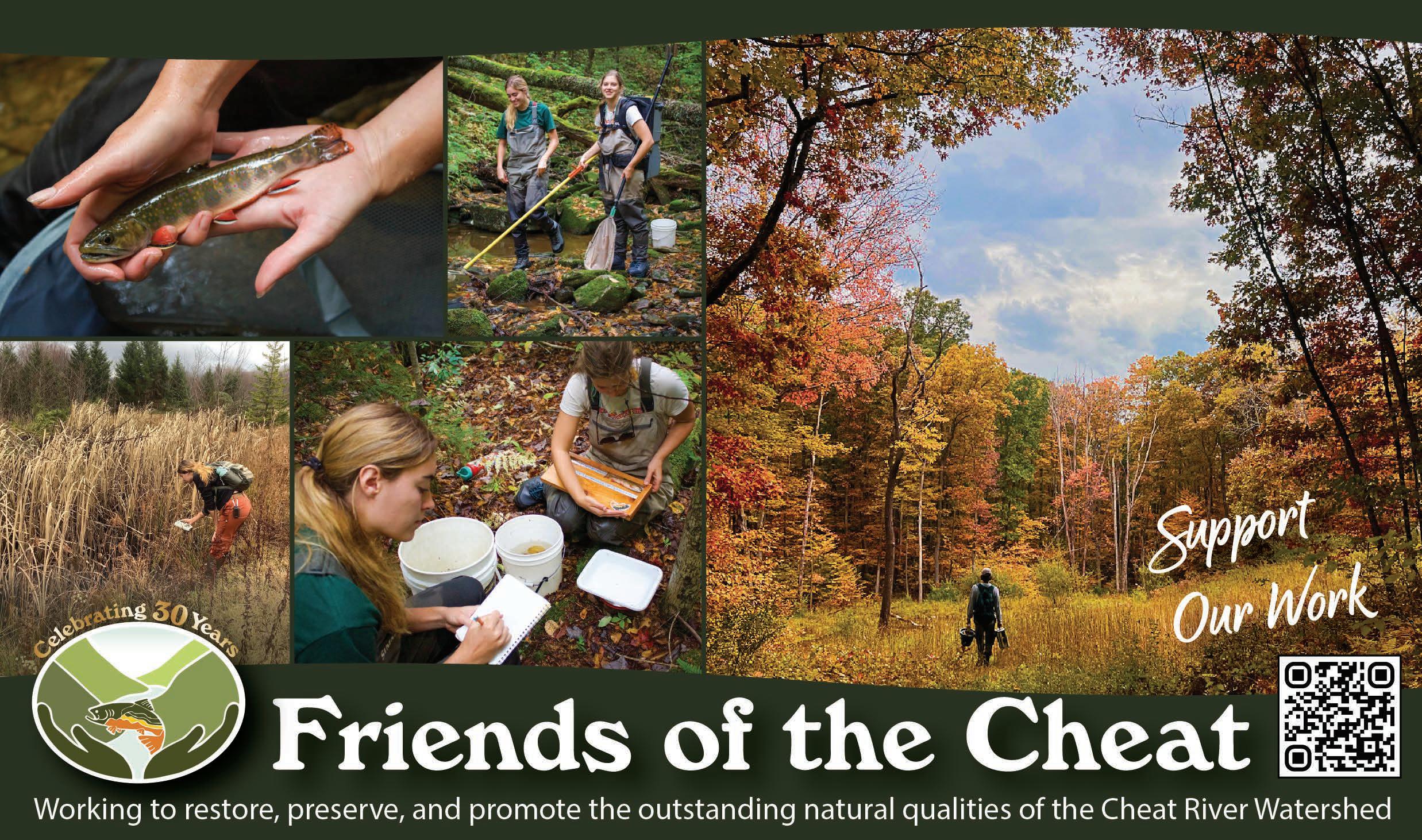

runoff from clearcut timbering, and other forms of pollution choked the aquatic life and damaged the sensitive riparian ecosystems of many streams throughout the state. Orange-stained rocks still exist today, serving as a reminder that whole stretches of river were once considered dead, unable to support fish or insect life. Watershed advocacy organizations like Trout Unlimited, Friends of the Cheat, Friends of the Blackwater, Save the Tygart, Friends of Deckers Creek, and West Virginia Rivers have focused on local stream restoration as a major component of their missions. As a board member of Friends of the Cheat, I’ve seen firsthand the positive power of these collective efforts. What was once considered an impossible task of restoring an entire watershed has become an ongoing story of resilience and recovery. Today, anglers can catch fish in places that, just a generation ago, seemed permanently lost.

When I’m out on the stream and see mayflies coming off the water, they’re a reminder of the countless hours these organizations—and their dedicated volunteers—spend treating acidic mine runoff, collecting samples, and monitoring water quality. The unique ecology of West Virginia’s waterways is something that needs to be protected for future generations to enjoy just like I have, and I’m proud to play a small part in these ongoing efforts.

For me, fly fishing is both a physical activity and a spiritual pursuit, allowing me to step away from the constant connectivity of the real world. Whether the flies I’ve learned to tie over the years entice a fish or not, the simplicity of being on a stream in a mountain valley with my dad and a few friends is what it’s all about. I’ve come to see fly fishing not as a pastime, but as an important part of my well-being. There never really is a bad day on the water. w

Chris Wade is a wealth management advisor and aptly named angler based in West Virginia. When he’s not landing a perfect drift, you can catch him chillin’ with his wife and two pups.

Left: Dylan Jones. Center and right: Chris Wade

THE PERFECT PALETTE

Words and photos by Brett

Rothmeyer

I would argue that, for outdoor enthusiasts up and down the East Coast, fall is the best season to participate in our respective activities. For mountain bikers, autumn offers up not only cooler temperatures, but also heroic trail conditions. The slippery mud of spring and the dusty unpredictability of summer give way to tacky perfection. The muggy rides to swimming holes are replaced with all-day adventures in the crisp air.

The desire to queue up camping trips rises a bit higher when the nighttime temperatures make crawling into a sleeping bag feel cozy and inviting rather than sweltering and miserable.

I sit on the front porch watching the steam rise from my coffee mug. It’s morning during the closing week of August, and already I’m in jeans and a flannel shirt. There’s a noticeable change in the air. While most of the northern hemisphere is desperately trying to hold onto what is left of summer, I recognize the beginnings of fall. Summer’s humidity fades like an old injury—you’re not sure if it’s gone at first and then realize a forgotten comfort you haven’t noticed in some time. On my morning trail ride, an hour goes by before I stop for a quick drink and notice I haven’t pushed the sweat out of my helmet pads even once. The leaves of the forest remain green, and the trail is a bit dusty, but deep down, I know fall is not far off.

I’ve long held the sentiment that summer is for flings, and fall is where real love is established. My lifelong affair with cycling may have begun in the summer, but it wasn’t until that first October after purchasing a mountain bike that it became all-encompassing. My early days of mountain biking were a trial by fire, as my road cycling legs propelled me down the trail faster than my burgeoning handling skills could manage. The weekdays spent on my local trails, followed by weekends of racing in Western Pennsylvania’s Month of Mud series, solidified my growing obsession.

Years later, I began to combine my loves of photography and cycling. At first, I would toss my old film camera in my race bag and snap a couple of frames in between racing and hanging out. It wasn’t long until I realized I had more potential as a photographer than a bike racer. Nailing quality photos quickly became more important than any hopes of impressive race results. The quest for better photographs spiraled out of control, and by luck or stubbornness, I managed to carve out a small career. Most of my work, like my passion, remains rooted in cycling. I now spend the better part of the year on the road, shooting events and chasing down stories for various outlets.

Along with providing ideal conditions for riding, the fall season delivers the same for photography. The foliage creates a vivid palette, turning even the simplest frames into painterly visions. Placing a rider, runner, or climber into the scene tends to evoke wanderlust in even the most tepid of the outdoorcurious.

As a photographer and mountain biker, my awareness of fall’s seasonal perfection—and its brief window—are at the forefront of my mind each year. Maximizing my time both on the bike and behind the camera has become my modus operandi while chasing color from Big Bear to Snowshoe and beyond. I’ve been lucky enough over the last several years to visit trail networks far and wide during the fall season, and the golden cinnamon ferns that line Big Bear’s rugged trails in late October possess a special kind of magic found nowhere else.

Above: Jason Cyr is no stranger to the big and burly lines on the trails around Davis, WV. From hucks to slabs and rock gardens to gaps and vertical roll-ins, Cyr can do it all. But for steep rock moves, it can be hard to convey just how steep they actually are. This is a good example of when your lens choice can make a big difference. Getting up close to the feature and rider with a wide-angle lens, think 20mm or wider, can give the viewer a sense of just how steep the terrain really is.

Previous: When surfers get barreled, they call it being in the green room. Scott Williams is performing the mountain biker equivalent in the gold room. A splash of falling maple leaves in the foreground add some dramatic effect. Pitted, so pitted.

The trails of Big Bear light up when their Jurassic-sized ferns go from green to golden yellow, providing dramatic scenery for an already dramatic rock drop.

Previous, top: A combination of early morning light and a little bit of fall color can add a lot to a photo. Getting up early or staying out until sunset can be a big help when chasing fall photographs.

Previous, bottom: Dry years, rainy years, it all has an impact on the tonality of the foliage, but Big Bear’s ferns always deliver an impact.

For photographers and mountain bikers alike, the wilds of West Virginia during autumn provide the perfect palette for creating stunning imagery, all while enjoying world-class singletrack. In its brief perfection, fall provides us with the inspiration to get out and make the most of it. The fleeting colors and winter’s inevitable return fuel the outings well into November. The camera captures these moments of brilliance in fractions of a second, but the feeling of those images will carry me throughout the year until fall comes around once again. w

Brett Rothmeyer is a photographer and writer based in Pittsburgh, PA, who pines to be flying through The Pines on a bike at Big Bear when the ferns turn orange every October.

Above: Scott Williams climbs through a leaf peeper’s dream on an unknown trail deep in the backcountry.

THE SUN LOVERS

By Nikki Forrester

We hop into the National Park Service vehicle and begin winding our way along backroads toward the Gauley River. The roads are steep, chunky, and narrow, requiring us to move slowly and stay tuned to oncoming traffic. Eventually, we turn onto an old railroad grade that follows the curves of the river upstream. When I think of the Upper Gauley, I envision massive flows of water, churning rapids, and raucous boaters eager for carnage. But on this late summer day, the river is calm and low. Instead of a raging torrent, I see a trickle wending its way through giant boulders that are typically hidden beneath the notorious rapids.

As we navigate our way down the road, we spot a Cooper’s hawk flying from branch to branch. Then, Doug Manning, a biologist at the New River Gorge National Park and Preserve, hits the brakes to point out a fern growing on a small cliff on the side of the road. We get out to look at a walking fern, whose elongated, arrowshaped leaves arch down the shaded rock face. When the leaf tips make contact with the rock, they establish roots that give rise to new ferns, allowing the plant to essentially walk across the landscape. After a brief, awe-filled moment, we get back in the car to continue on our journey. The walking fern is a treat to find, but it’s just one of many amazing plants we’re about to see.

Today, our goal is to visit several riverscour prairies, a unique type of plant community created by raging rapids and maintained by periodic floods. In West Virginia,

Top: A riverscour prairie on the Gauley River, photo by Dylan Jones. Bottom left: A Liatris scariosa flower blooms in early August, photo by Nikki Forrester. Bottom right: National Park Service biologist Doug Manning gazes at a sunny riverscour prairie, photo by Dylan Jones.

Clockwise from top left: Euphorbia corollata , photo by Nikki Forrester. Solidago simplex var. racemosa , photo by Dylan Jones. The stump of an invasive autumn olive tree that’s been treated with pesticides and dyed blue so scientists know it’s been treated, photo by Dylan Jones. Virginia spiraea, a federally threatened plant species; the world’s largest population of Virginia spiraea is in the Gauley River, photo by Dylan Jones.

the abundant whitewater that draws in paddlers from around the world provides the perfect environment for riverscour prairies. They occur on cobble bars, bedrock, and bouldery substrates next to steep sections of the Gauley, New, Cheat, Greenbrier, Tygart, Potomac, and several other of our state’s rivers. During flooding events, the rushing waters snap woody plants from their roots, making room for sun-loving plants that thrive in the open and inundated conditions.

“There’s a whole bunch of state-rare plants that occur in the New River and Gauley that don’t occur anywhere else,” says Stephanie Perles, a plant ecologist for the Eastern Rivers and Mountains Inventory and Monitoring Network (ERMN) for the National Park Service. In West Virginia, this network monitors the New River Gorge National Park and Preserve, the Gauley River National Recreation Area, and the Bluestone National Scenic River. The riparian habitats that line the banks of these rivers, including riverscour prairies, comprise just 2% of the parks’ 88,000 acres but contain a whopping 65% of the parks’ plant diversity. Roughly 50 plant species that are rare in the state of West Virginia occur only in these riparian areas, and some can only be found in riverscour prairies.

The riverscour prairies of the Gauley River are home to the world’s largest population of the federally threatened plant Virginia spiraea (Spiraea virginiana). The Monongahela Barbara’s-buttons (Marshallia pulchra), a plant that produces beautiful firework-shaped flowers with curly lilac petals, solely occurs in the riverscour prairies of West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and Kentucky. Similar to the quintessential prairies of the Midwest, riverscour prairies in West Virginia host tall grasses, including big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii ), switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), and Indian grass (Sorghastrum nutans). These habitats are also home to highly specialized plants like riverbank goldenrod (Solidago simplex var. racemosa) and wild blue indigo (Baptisia australis), whose dried seed pods sound like a rattlesnake when they’re touched.

The few shrubs and trees that do establish in riverscour prairies are gnarled and battered by the floodwaters, preventing them from growing too straight or tall. In contrast, riverscour prairie plants are well

adapted to withstand floods, submersion, sun, and heat. They have deep roots that anchor them into the cobbles and rapidly resprout after scouring events. And during the dog days of summer, these deep roots allow riverscour prairie plants to access water and nutrients despite the extremely hot and dry conditions.

RIPARIAN RARITIES

Manning checks his map before pulling off in a grassy nook on the side of the old railroad grade. We hike down a steep, rocky drainage before popping out into a riverscour prairie below a rapid on the Gauley. The first thing I notice is the towering flowers, filled with bees, butterflies, wasps, and other pollinators. The plants sprout from tiny crevices between the cobbles and boulders, where just a trace amount of soil can be seen. We scurry across several large boulders and perch atop one overlooking the river. At a flow of around 250 cubic feet per second (cfs), we’re shocked to spot the bright reds and greens of kayaks eddied out above the rapid.

“This is one of the sites where we’re doing recovery work for Virginia spiraea,” Manning tells me while we wait for the kayakers to paddle by. Virginia spiraea is a federally threatened plant, with most populations containing just a few individuals. Over the past several decades, scientists have documented declining populations of Virginia spiraea throughout the Gauley and Meadow rivers. These declines are primarily attributed to habitat destruction, invasive plants, and a reduction in scouring events due to upstream dams.

The National Park Service started their recovery work on Virginia spiraea in 2020. “The first thing we did was go out and monitor all of the Virginia spiraea that was known to occur in the Gauley River National Recreation Area, including the Meadow River,” says Manning, noting that some of earliest data collected on the species was from the 1990s. “Most of the sites seem to be stable, but we had 10 sites where we determined that Virginia spiraea had declined from previous monitoring efforts.”

To support Virginia spiraea populations throughout the New River Gorge National Park and Preserve, Manning and his colleagues remove invasive plants that

shade out the rare and threatened plants. Walking along the riverscour prairie, Manning shows me a bright-blue stump of an autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata), one of the most common invasive species in riverscour prairies.

“In areas where we have Virginia spiraea and other rare species, we take a very focused approach to how we treat invasives,” he says. Instead of doing a broad application of pesticides, the scientists cut down the invasive plants and daub the exposed stumps with chemicals so they don’t resprout. “There’s really no risk to having any sort of spill or non-target effects,” he describes. They also apply potent blue dye to the stumps so they know which invasive plants have been treated.

Along with removing invasive plants, Manning and his team augment the declining populations. “The good news for Virginia spiraea is that it reproduces asexually really, really well,” Manning says. Since 2023, the team has tried several methods for increasing populations of Virgina spiraea. One approach involved taking fresh cuttings from young plants, sending them to a botanical garden in Delaware for propagation, and then replanting them in the riverscour prairies once they reached a larger size. While the approach was quite effective, Manning says another approach called live staking was much faster and easier. “We just take a hardwood cutting, create a little pilot hole using a piece of rebar, and then plant the cutting,” he says. The cutting then grows roots, anchors itself into rocks, and grows a new plant. So far, Manning and his colleagues have planted 46 Virginia spiraea cultivated from cuttings at this particular site.

Manning also works with local landowners to recover the threatened species throughout the region. Using historical data as a guide, Manning sent letters to 19 local landowners to inform them that the threatened plant might occur on their properties. “It was really heartening to see the number of responses we got,” he says. Manning helped educate landowners on how they could protect Virginia spiraea on their property. Several landowners were also eager to share cuttings with Manning and his team so they could establish the plant within the bounds of the Bluestone National Scenic River. Although Virginia spiraea likely occurred along the Blue -

stone River historically, there haven’t been any confirmed sightings of the plant for decades. Now that Virginia spiraea is planted back on federal land, it’s protected by federal law and policy. “It’s been a really cool project in terms of the success that we’re having and seeing other people wanting to join this effort,” says Manning. Other national parks, including Great Smoky Mountains, are now working on conserving Virginia spiraea.

MONITORING CHANGE

Ultimately, the long-term success of Virginia spiraea and riverscour prairie communities requires maintaining the periodic floods that provide the open, sunny habitats these plants need to thrive. To keep tabs on how and why the riverscour prairies of the New River Gorge region are changing, Perles and her team at the ERMN conduct regular monitoring to survey the abundance of native plants, tree cover, and invasive species. This information is then passed along to biologists, like Manning, to help them devise good management strategies.

There are nine riverscour prairie sites in the New River Gorge National Park and Preserve that Perles and her team have monitored since 2012. “I wish we could raft in, but when there’s enough water in the Gauley to raft, the riverscour prairies are usually underwater,” she says. After a long hike in, the scientists set up one-square-meter plots in the same places along the riverscour prairies every year. The team records every plant that’s growing inside the plot, how much area each plant takes up, and what portion of the plot is shaded by trees and woody shrubs.

Then they move onto the next plot, often sampling up to 60 plots per site depending on how large the riverscour prairie is.

Throughout the day, the researchers document any invasive plants they see. Over the past 13 years, they’ve found that invasive species, including autumn olive, sericea lespedeza (Lespedeza cuneata), purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), Japanese knotweed (Polygonum cuspidatum), and multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora) occur at low abundance in many prairie sites.

The team has also observed a decline in the area covered by grasses, sedges, and rushes in riverscour prairies. “That means the prairie grasses like big bluestem, little bluestem, switchgrass, and cordgrass that are unique to these habitats are decreasing,” Perles says. “We are slowly losing native plants from these habitats as well.”

On a brighter note, the team hasn’t seen any changes in the amount of area covered by trees and shrubs. “Our concerns about woody plants increasing and shading out the diversity of prairie plants hasn’t been proven yet, thankfully,” she says.

One outstanding question is how the occurrence of scouring events has changed over time as a result of upstream dams regulating water temperature, timing, and volume. Manning says he’d like to put gauges and cameras along the New, Gauley, and Bluestone rivers to better understand what flow rates equate to scouring events. Although the Bluestone and Summersville dams have changed water patterns from what they were historically, Manning says they also provide opportunities to facilitate scouring events. “Ideally, someday we will collaborate with the Army Corps of Engineers to facilitate high-water events that can help maintain this habitat,” Manning says.

RIPE FOR RECOVERY

In a rapidly changing world with limited funding and staff, it can be challenging to determine which regions, habitats, and species to focus on for conservation and restoration projects. The New River Gorge National Park and Preserve is no different. With 88,000 acres to manage and a handful of employees, park staff at the New have to choose where to focus their efforts. “The river corridor came out as a high priority, both ecologically and for visitor experience,” says Perles.

Removing invasive plants and recovering Virginia spiraea populations are just two pieces of the conservation puzzle. Maintaining riparian plant communities and riverscour prairies far into the future also requires some thoughtful efforts by those who develop riverfront properties and enjoy paddling these amazing rivers. From selecting low-impact sites for development to avoiding trampling rare plants during a lunch stop, we can help preserve these rare and special places.

After watching the paddlers navigate Lost Paddle rapid, Manning shows me several Virginia spiraea plants: some that naturally occur and others that were grown from cuttings. Although it’s past their flowering season, I admire the soft, green leaves and robust form of the sprawling shrubs. They don’t seem to have any problem tolerating the direct sun exposure. I, on the other hand, am feeling overheated and dehydrated.

We pack up our gear, hike back uphill, and move onto another riverscour prairie site, one Manning has never visited before. It looks quite different than the previous prairie, with a flatter cobble bar, fewer stunted sycamore trees, and fields of waving grasses. Manning tells me that no two riverscour prairies are alike. The riverscour prairies on the New host different plant communities than the ones on the Gauley or the Bluestone. Each is shaped by the unique features of the surrounding river and forest.

On this late afternoon in early August, it doesn’t take long for the blazing sun to warp my brain into thinking about nothing but water. We hike out as quickly as our bodies allow and drive a few more minutes up the road to a dirt pull off. I rush down to the river, scramble up a large boulder, and plunge into a deep pool of cool, clear water. Floating on my back, I look around, taking it all in—the bright blue sky, puffy white clouds, tree-covered hillsides, darting dragonflies, and, of course, the endless rare plants that live along the river corridor. “One of the reasons I love Viriginia spiraea is because I get to work in a beautiful place like this,” Manning says. “It’s the perfect place to be on a West Virginia summer day.” w

Nikki Forrester is co-publisher of Highland Outdoors. She never ceases to be amazed by the Mountain State’s rare and special plants. Dylan Jones

THE HEART OF WV LIVE MUSIC

FULL MENU SERVED DAILY

WV'S BIGGEST MICROBREW SELECTION

FREE AFTERNOON CONCERTS ON WEEKENDS

A SHOT IN THE DARK

By Dylan Jones

On October 10, 2024, I got a text from a friend asking if I was going to watch the Northern Lights that night. Supposedly, the internet was abuzz with chatter of a severe geomagnetic storm, which was forecast to set the sky aglow across the Mountain State.

I felt a brief pang of excitement, immediately followed by skepticism. Growing up in West Virginia, I remember reports on the evening news (which is how people learned of things before the days of social media) discussing the possibility of witnessing the aurora borealis. But they never panned out for me. It was either during some wee hour of the morning, or the phenomenon simply wasn’t visible. At best, some professional astrophotographer with a fancy camera rig would capture a hint of red in the sky, barely perceptible to the advanced optics of a DSLR camera, and certainly not visible to the naked eye.

Nevertheless, I’m a self-described nerd when it comes to weather and astronomy— even more so when dealing with the niche topic of space weather. As such, I let the excitement build while trying to moderate it with premeditated disappointment. Starting at dusk, I continually went outside my home in the middle of Davis to stare intensely at the sky with hopes of seeing something extraordinary. At one point, I looked to the northeast and saw what appeared to be a pinkish glow. Not letting myself get too excited, I figured my eyes were playing tricks on me, or that the hue was from light pollution.

Looking to the northeast, the intense glow and pillars of a substorm light up the night sky, photo by Nathaniel Peck.

To double check, I got out my fancy camera and took a long exposure shot and freaked out as the camera confirmed what my naked eyes had seen. The sky was a solid dome of pink, with purple and blue hues to the north. Finally, the Northern Lights were happening in West Virginia, and I could actually see the cosmic show.

SHOW TIME

On October 9, 2024, the NASA Solar Dynamics Observatory reported a strong solar flare—a powerful burst of electromagnetic radiation from our sun’s atmosphere—that peaked at 11:47 a.m. Eastern time. This X-class solar flare, the highest level of intensity, triggered a coronal mass ejection (CME), which is a magnetized cloud of plasma, that barreled toward Earth.

Some 30 hours later, the CME reached our home planet’s magnetosphere, causing a geomagnetic storm that unleashed a stunning display of lights across the Northern Hemisphere. Skywatchers and astrophotographers across the country, including folks as far south as Texas and Florida, were treated to an unforgettable show.

I ran inside, shouted to my wife, Nikki, that it was go-time, and scrambled to throw my camera gear in a backpack. We hopped in the car and sped to the top of the nearest mountain to post up in a spot free from light pollution and with a wide-open view of the cosmos.

I figured we’d enjoy the novelty of seeing the faint glow with our naked eyes and be stunned by the images on the camera. But as I set up the tripod, the northern sky lit up in green and yellow tones as if a massive stadium was just over the ridge. The dome of light pulsated, fluctuating in color tones reminiscent of a Rastafarian flag.

The pictures on the camera screen were even more mind-blowing, but that didn’t matter, because the show we were watching with our own eyes left us speechless. A substorm, which occurs when charged particles transfer their energy from Earth’s magnetosphere into the ionosphere, further ignited the scene with dancing magenta waves speared with bright yellow light pillars. Nikki and I shouted all the expletives you’d expect to hear from two awe-struck humans.

FIFTY-FIFTY CHANCE

David Johnston, a photographer based in Randolph County, was prepared. He’s been photographing the night sky for over a decade and monitors space weather websites and apps to stay up to date for events like the aurora borealis. “I’ve gone out on nights where there was a good possibility, and nothing happened; you never really know for sure,” Johnston said.

Auroral displays are notoriously difficult to forecast. The complex interactions between charged particles in the magnetosphere are tricky to model. We have a hard enough time predicting weather here on Earth, even more so with space weather emanating from the sun some 93 million miles away. “Detecting the characteristics of an approaching CME, like how strong it is and its north-south orientation, which factor into whether or not there will be a visible aurora, involves a lot of uncertainty,” Johnston said.

But the severe alert from the X-class solar flare had Johnston and many others ready to head for the hills. “It became increasingly apparent that the

Left bottom: An array of red, yellow, and green pillars over a bog near Canaan Valley, photo by

Above: Anvil Rock in the Dolly Sods Scenic Area is illuminated by a glow from the aurora borealis, photo by David Johnston.

Left top: The iconic New River Gorge bridge looks especially stunning under the Northern Lights, photo by Jesse Thornton.

Dylan Jones.

possibility of auroras being visible down here in West Virginia was real and not just a pipe dream,” he said.

Johnston was joined by Nathaniel Peck, a photographer based in Maryland, who frequents the Allegheny Mountains for his shots. “I went up there thinking it would be a fifty-fifty chance, but I wasn’t gonna miss it,” Peck said.

The pair met up at the Dolly Sods Scenic Area and hiked out to one of their favorite spots along the spine of the Allegheny Front, away from the more popular cliffs of the Bear Rocks Preserve. Johnston and Peck shot sunset photos and then bundled up to wait for the sky to darken. At twilight, they both noticed a pinkish glow in the east, but Johnston, like me, figured the hue was from light pollution. He pointed his camera eastward and snapped a long exposure. “Lo and behold, the same deep pink appeared in the picture,” Johnston said. “It’s already happening, and it’s not trivial. The patterns and colors in the sky could change, not just minute to minute, but in some cases, over a matter of a few seconds.”

Peck set his camera up with a remote shutter so he could take a constant stream of photos while being able to experience the event himself. “It just got better and better as the night went on,” he said. “I did not dress warm, and it was so miserably cold and windy up there, but then the substorm started and I could actually

see the pillars. I just sat down on a rock and stared up, speechless.”

Matthew Grahovac, an amateur photographer from Northern Virginia, also made the trek up to Dolly Sods with his wife to catch the show. Grahovac had his auroral interest stoked in the fall of 2024 while on a backpacking trip in the Upper Peninsula (UP) of Michigan. Up yonder in the UP, the Northern Lights aren’t as much of a rarity, and an event was forecast to be visible during his trip, so he downloaded a space weather app and started paying attention. Much to his disappointment, the aurora wasn’t visible that night, but his interest was piqued.

Grahovac received the notification of the October 10 storm and rushed to his car. “My wife and I discussed going to Shenandoah National Park because it’s closer, but we figured it would be crowded and it has more light pollution than Dolly Sods,” Grahovac said. “Every time I’ve gone to Dolly Sods, it was clear, and I remember seeing the Milky Way brighter than I’d ever seen it in the East. I told my wife that we probably won’t end up seeing anything, but it’ll be an adventure regardless.”

While heading west on the highway, Grahovac noticed a pink glow to the north. He pulled off the highway to make sure he wasn’t losing his mind. “I’ll never forget that drive, it was like nothing I’d ever seen before,” he said.

After the moon dipped below the horizon, the Milky Way made an appearance, adding another cosmic dimension to the scene, photo by Matthew Grahovac.

They were even more stunned to arrive at Bear Rocks Preserve and see the peak red foliage of the berry shrubs reflecting the brilliant reds of the aurora. Once the moon dipped below the horizon, the Milky Way became visible, setting up some surreal shots. They stayed into the early hours of the morning then drove home, logging just two hours of sleep before work. But Grahovac said the sleep deprivation was worth it to witness something he won’t soon forget. “It was a very cool moment that I got to experience with the person I love,” he said.

BRIDGE TO THE STARS

Huntington-based photographer Jesse Thornton has been focusing on the night sky as his primary subject for a decade. When he got the alert of the October geomagnetic storm, he hurried east into the ancient chasm of the New River Gorge for a chance at a unique shot.

It’s worth mentioning that there was an auroral display visible in West Virginia in May of 2024, but with a faint glow that wasn’t visible to the naked eye, it paled in comparison to the October event. “I shot the May event along the Ohio River, and the image has a little patch of pink in the sky you can barely tell is there, and I thought it was the greatest thing ever,” Thornton said.

When he set up in the bottom of the New River Gorge, he was able to see the glow with his own two eyes. “It appeared as a very ominous, dark, reddish glow cast over the entire scene,” he said. “I’m amazed that the surface of the river was reflective of the color.”

Having only a sliver of sky visible meant missing some of the pillars that appeared for viewers, like those in the Allegheny highlands, who were perched above their surroundings. “Essentially I sacrificed what would have been a better light show to get the bridge shot,” Thornton said.

For Thornton, seeing one of the state’s iconic structures spanning one of the planet’s oldest rivers to the backdrop of a rare cosmic event is something he won’t ever forget. “As somebody that does wide-angle astrophotography, it was kind of the pinnacle of what’s possible here,” he said. “I was just ecstatic. It felt like a culmination of all the time and effort of the last decade put into one night.”

By the end of the cosmic light show, I experienced a heavy dose of what I like to call sublime insignificance—letting trivial troubles melt away while feeling part of something truly grand, regardless of how unfathomable the scale may be. Although I didn’t want it to end, the intensity of the substorm had clearly faded, and my hands were going numb. All good things must come to a close, and it was time to head home. Fortunately, the shared sense of awe and camaraderie from that magical evening lives on through the art of photography. The collective body of shots from that evening serve as a friendly reminder that, sometimes, the stars (and complex interplay of space weather) really do align. After decades of letdowns, I finally got to experience the Northern Lights, something I’ve dreamed of seeing since I was a kid, right here in the Mountain State. w

Dylan Jones is co-publisher of Highland Outdoors and plans to photograph the next aurora borealis display in, where else, but the Preston County village of Aurora.

ONE MAN’S TRASH

By Karen Lane and Amanda Smith

Locals say Trey Swartz embodies the Appalachian creator archetype. Eager to live his dream of climbing and creating in the New River Gorge, Swartz quit his blue-collar career in heating, ventilation, and air conditioning and moved to Fayetteville in February of 2021 to start his journey in jewelry making as the Southern Pillar Jeweler.

Like many West Virginia transplants, Swartz found community, creativity, and freedom in the hills. Swartz’s father grew up in Saltville, Virginia, an old salt mining town, then moved to the suburban sprawl of Northern Virginia to raise his family. “I didn’t really know anything about Appalachia until I moved here and started climbing,” Swartz says. “Since then, I’ve learned so much about my family’s extensive Appalachian roots. I’m pretty much the first generation of my family to not grow up in the mountains, but they drew me back in and feel like home.”

He came to Fayetteville for rock climbing but soon discovered his love for crafting jewelry using raw materials that are found throughout the region. Now, he spends hours foraging for these treasures along the banks of the New River and high up along the cliffline that rims the Gorge, seeking out special objects to set in custom-sculpted bevels.

One day while Swartz was out climbing at Hawks Nest Dam, he spotted a blue rock embedded in the trail—a stark contrast to the grays and oranges of the region’s classic iron-rich sandstone. “The rock looked almost glass-like,” he said. Unsure of its composition, Swartz took the mineral home to begin his work of setting it in silver. Later that week, he got to talking to a local at the hardware store who told him the mineral was not a mineral at all, it was slag. Or, as the man described it, trash.

ELEMENTAL RELICS OF THE PAST

The New River cut through rock layers that date back over 300 million years, creating one of the planet’s oldest gorges. The erosion-resistant Nuttall sandstone that forms the dramatic hundred-foot cliffs is popular with rock climbers, while the surrounding shales and coal beds below provide geologic evidence of the ancient swamps and river deltas that once characterized the region.

Along the banks of the New River and its tributaries, one can find more than sandstone cliffs and seasonal wildflowers. Mixed among the cobbles are pieces of slag, rock formed as a by-product of smelting ore that now dot the landscape as relics of West Virginia’s industrial past.

Coal slag is the most common variety of slag found in the New River Gorge. It’s visually similar to volcanic rock in that it’s lightweight, filled with small holes, and often black or dark brown. This slag forms when waste rock layers, such as shale or sandstone, are burned along with coal. The intense heat melts and partially recrystallizes the minerals, creating a porous, brittle stone. Coal slag had multiple industrial uses after production—crushed for use as an abrasive, incorporated into road surfacing, or used as fill material. It’s often found along Appalachia’s rugged riverbanks,

redistributed by floods. It can even be seen floating in the water due to its porous nature.

Iron slag, though less common, can also be found along certain stretches of the New River and its tributaries. This material originated in blast furnaces that processed iron ore in the 19th and early 20th centuries. During smelting, impurities in the ore, along with silica, alumina, and other elemental oxides, floated to the top of the molten iron. Workers skimmed off this molten waste, which then cooled into solid, glassy fragments.

Swartz finds immense beauty in these waste products, overlooked by most who spend time on the riverbanks. Coal slag can be blue, green, or rust-red, depending on the mineral content of the original ore and furnace conditions. “Every once in a while, you’ll come across one with blue and green stripes, or even tiny specks of embedded metal and opal-looking sparkles,” he says.

FROM SLAG TO SLEEK

Swartz is a self-taught artist with a love for scavenging materials. He began his jewelry making career with river glass and chunks of coal. “The first time I used river glass was a few years ago, over the winter when I was out of cabochons [highly polished, unfaceted gemstones] I had bought before I was cutting my own.

Trey Swartz climbing High Times (5.10+) at the Bridge Buttress in the New River Gorge, photo by Karen Lane. Previous: Swartz carefully crafts custom rings from slag found in the New River Gorge, photo by Karen Lane.

I saw a piece of glass and wondered if I could use it, and it worked perfectly,” Swartz says.

Rings with polished chunks of coal came next. “I watched a friend make a ring and then he let me use his bench to make one,” Swartz says. “I learned the craft by watching online videos and playing with metals in my shed during the pandemic, then taking more extensive classes over the years.”

After dialing in his craft, Swartz entered and won a business plan competition and used the winnings to purchase lapidary equipment—a set of tools and machines that shape, grind, cut, and polish stones. One of his most “professional” tools is a cabbing machine, which has six diamond-coated wheels used to grind, shape, and polish gemstones. These essential tools allowed Swartz to transmute the raw chunks of slag and quartz into the beautiful treasures he now sells.

Once Swartz has his slag cabochon ready, he uses his smithing skills to shape silver pieces with hand tools like pliers, files, and hammers. “I use a torch to solder them together to create the ring. Each piece is made one of a kind to fit each stone,” he says.

Swartz loves the hunt for slag, which allows him to spend time outside and scavenge for unique materials most people would overlook. While spending time outside is a perk of the craft, Swartz must balance that with time spent inside his workshop. A basic ring takes about an hour or two for Swartz to complete, with more complex designs taking upwards of four hours per piece. “I’ve gotten very quick and efficient over the years,” he says. “I like making several at once in batches of similar styles and may spend up to ten hours in one day working on a set.”

FROM TRASH TO TREASURE

To Swartz, slag is far more than a waste product—it’s a record of the industrial methods, labor, and economic history of the Appalachian region. Swartz says found objects are far more inspiring to him than the sorts of precious stones that are easy to order online. He gets creative satisfaction from making jewelry out of these forgotten materials. Or, as he puts it, “I like trash.”

Alongside his slag rings and pendants, some of his favorite materials to work with are river glass, sandstone, and coal. These works are created and sold back to people who have an interest in owning a piece of West Virginia’s history. “Once their trash, now their treasure,” he says.

You can find Swartz in the Wild Kind Artisan Boutique, his shop in Fayetteville, where he teaches ring-making courses in collaboration with another jeweler. When he’s not turning trash into treasure, he’s out climbing with his dog, Coal, in tow. w

Karen Lane is a climber and photographer living and working in Fayetteville. Her work showcases the landscape and rock climbing scene of the New River Gorge to bring East Coast representation to outdoor media.

Amanda Smith is a climber and geologist living and working in Fayetteville. She works with local organizations to keep climbing areas safe and to educate climbers about best environmental practices on the wall.

Clockwise from top left: Chunks of slag, photo by Karen Lane. An array of Trey Swartz’s rings, photo by Karen Lane. Swartz working in his home workshop, photo by Braiden Maddox. Polished pieces of slag, photo by Karen Lane.

ADAM POLINSKI

By Dylan Jones

I love Coopers Rock State Forest. Like many West Virginians, I’ve enjoyed this magical landscape along the eastern rim of the Cheat River Canyon for as long as I can remember. From scampering around the towering rock corridors with my parents as a klutzy child to my formative years in high school and college hiking, mountain biking, and rock climbing (still with plenty of klutzy moments), the countless hours I’ve spent at Coopers Rock have played a significant role in shaping who I am today.

Coopers Rock also significantly shaped Adam Polinski, a Morgantown resident who’s been a mainstay among the rocks and trails for over 40 years. One could argue that Adam has, in turn, significantly shaped Coopers Rock through his involvement with the Coopers Rock Foundation (CRF), of which Adam is a founding member.

I first met Adam Polinski in the late 2000s, when I was wrapping up my undergraduate days at West Virginia University (WVU). While taking a parks and recreation course, my classmates and I did some volunteer work with the CRF. Next to a pile of tools, work gloves, and safety glasses, Adam stood out as a stout, energetic man with bright eyes, a bushy beard, and a permanent smile. When the volunteer shift ended, I stuck around and helped Adam clear some

downed trees. He showed me how to improve my axe technique as we talked about biking and climbing, immediately bonding over our shared love of the West Virginia mountains.

If you’ve spent any time at Coopers Rock, odds are you’ve seen Adam at some point, whether it’s out on the trail or during a CRF event like the annual WinterFest celebration. And if you haven’t had the pleasure of meeting him, you’ve undoubtedly enjoyed the fruits of his labor from the countless hours (he estimated around 10,000) he’s put in over the decades.

During my meandering conversation with Adam, I recalled that my familial connection to Coopers Rock runs deep. My great aunt, Carol Headly, was a founding member of the CRF, and my grandmother, Shirley Jones, had a bench dedicated to Aunt Carol upon her passing, which still sits along the paved path to the ADA-accessible overlook.

If you love Coopers Rock as much as I do, I hope you’ll enjoy my conversation with Adam, someone I consider synonymous with one of West Virginia’s most iconic natural wonders. This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Tell me about your upbringing.

My father was from Ashland, Kentucky, and my mother was from Gary, Indiana. They married and moved to New York City, then to New Jersey, where I was born in 1963. The things I most remember from those days are riding my bike and going fishing, two things I still do today. In the middle of tenth grade, my dad got a new job with the Department of Energy in the South Hills of Pittsburgh. I didn’t adjust well to my new high school. I was so far out of the mainstream that I referred to myself as a fringe nerd. I didn’t make that many friends and I cut class a lot, but not to do delinquent things. I hung out in the library and read. My grades were poor, but my learning continued. When I applied to college, I got accepted to two schools: a Penn State branch campus and good ol’ WVU.

What was your introduction to West Virginia?

I did a solo backpacking trip in the Laurel Highlands of Pennsylvania in eleventh grade, where I met four WVU forestry students out in the woods. That chance meeting opened my eyes to WVU and to people I could relate to. Because of that experience, I ended up going to WVU to major in forestry. My first backpacking trip in West Virginia was to Dolly Sods during my freshman year in October of 1981 with some dormmates, which is hilarious to think back on. I brought along my chemistry workbook thinking I was going to be responsible and do homework in my tent. It was way colder than we expected; there was snow on the ground and it was really windy. We struggled to set up the tent and then cooked dinner in the freezing dark. I was like, “There’s no way I’m doing chemistry homework!”

What role has Coopers Rock played in your life?

When I started at WVU, some kid on my dorm floor had a car and said, “Let’s go to Coopers Rock.” I said, “What’s that?” I remember going up and parking near the overlook and running into the woods, and was wowed by the big rocks and trees, just thinking Man, this is so cool . My next memory is getting back to my dorm room and realizing I had lost my wallet. There were Adam

Polinski

already plenty of jitters as an incoming freshman, and the last thing I needed was to lose my wallet. I organized a group of dudes from my floor to go back and look for it and offered everyone pizza. I couldn’t guarantee we’d find the wallet, but I guaranteed we’d have pizza. Sure enough, one of the guys found my wallet. Some Good Samaritan noticed it and placed it on a rock in clear sight. I was so relieved. I had my first two Coopers Rock experiences in 24 hours and had something dramatic happen both times. I had no idea that Coopers Rock would become such a large part of my life.

After school, at age 23, is when big things happened for me. I became a vegetarian, I started doing yoga, and I started rock climbing with college friends. Skiing and rock climbing at Coopers Rock were huge influences in my life. Over time, it evolved to the point where Coopers Rock was the place that meant the most to me, and it has increasingly become more so. It has all these different facets as a state forest. Everyone loves Coopers Rock for their own reasons and that complexity fascinates me.

What role has Coopers Rock played in West Virginia’s outdoor history?

It was purchased by the state from a lumber company in 1936; most of that land is still part of the Coopers Rock State Forest today. Early on, it was visited by the public primarily for sightseeing at the overlook, which is why the road, parking lot, and restrooms