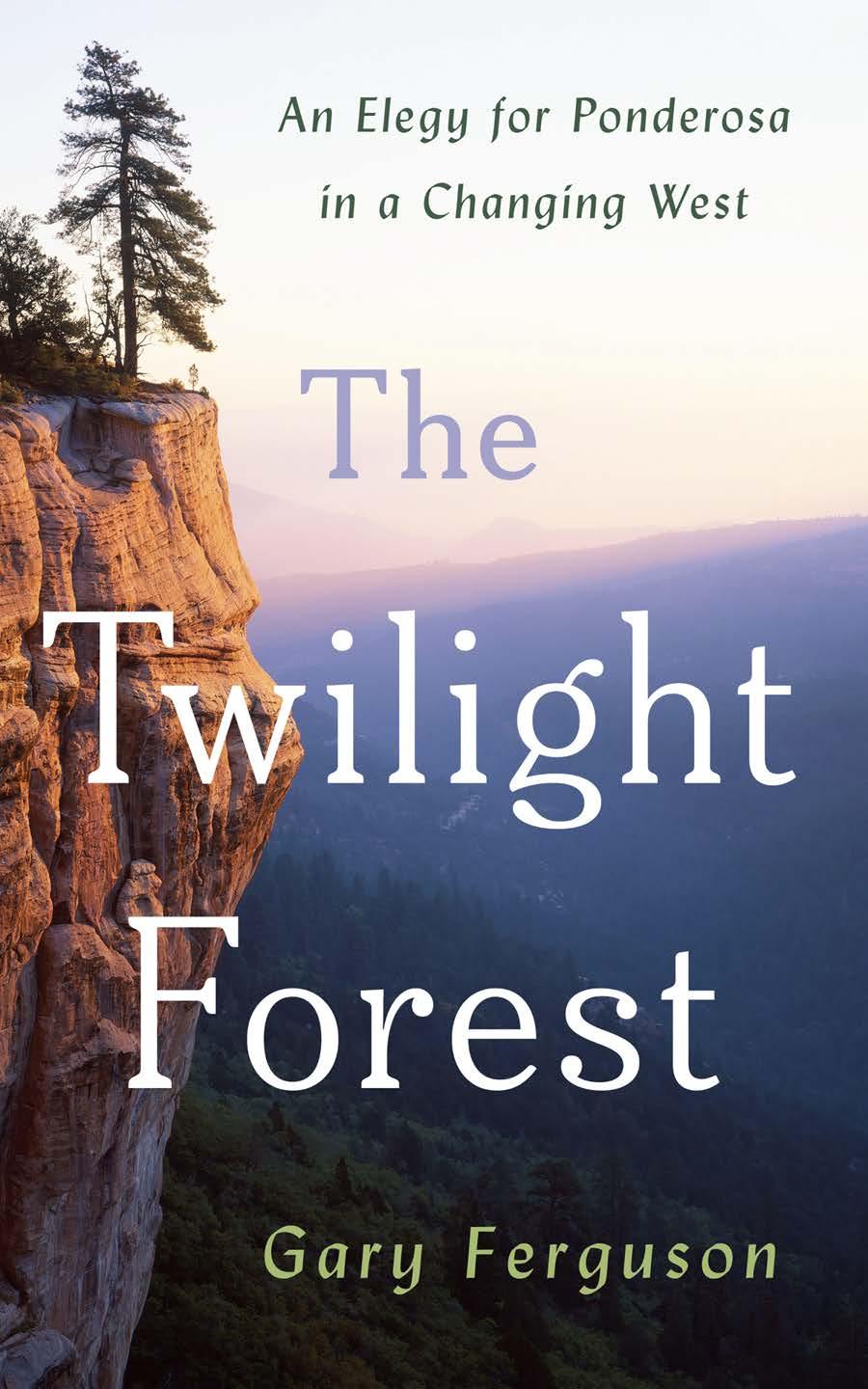

The Twilight Forest

An Elegy for Ponderosa in a Changing West

Gary Ferguson

© 2025 Gary Ferguson

Art by Ema West

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher: Island Press, 2000 M Street, NW, Suite 480-B, Washington, DC 20036-3319.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2025936289

All Island Press books are printed on environmentally responsible materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Keywords: American West, Arizona, California, Colorado, John Muir, Mogollon Rim, New Mexico, ponderosa pine, Southwest, Utah, canyon, climate change, drought, ecology, forest, forest fire, natural history, wildfire

For Mary, who, even in this troubled world, shows me how to dance.

Contents

Chapter One 1

Chapter Two 9

Chapter Three 17

Chapter Four 29

Chapter Five 37

Chapter Six 43

Chapter Seven 63

Chapter Eight 75

Chapter Nine 89

Chapter Ten 97

Chapter Eleven 111

Chapter Twelve 123

Chapter Thirteen 139

Chapter Fourteen 153

Acknowledgments 157 Selected Sources 159 About the Author 163

Chapter One

I’m in the great wild open of southern Utah, standing on a slab of rock the size of a school bus, swooning over a view to the south stretching on for hundreds of square miles, clean into Arizona. A perfect garble of red rock turrets and trees and scoured canyons—startling in the best sense of the word. A landscape that seems conjured by wizards.

I’ve been on the road for three days now, drifting south from Montana on a loose toss of quiet highways—past the Tobacco Roots and the Ruby Range, the Tetons and the Wasatch, nudging my way toward New Mexico—the starting point for what will be a monthlong trip. I was hoping yesterday to get farther down the road. But the sky was so clean, the mesas so full of shimmer, that getting to this slice of canyon country seemed plenty far enough. Last night I slept outside, under a sky as black as Raven’s feathers, shot full of stars.

This morning I’m back to a game I often play in this part of the Southwest. It involves looking out across the red rock hoodoos and twisted canyons from some high place like this one, picking a point twenty or thirty miles distant, and then trying to imagine a walking route to get there. It’s ridiculously complicated. Yet no matter which

2 The Twilight Forest

maze of arroyos and canyons I pick, my instinct is to choose a path that, whenever possible, hopscotches between clusters of ponderosa— trees that show themselves easily, what with their soft green canopies shimmering in the sun. I know well how beautiful those open groves would be, their tall, clean cinnamon-colored trunks offering up an almost motherly comfort to the hardscrabble traveler. Especially on searing hot days like this one promises to be, when the ponderosa forest might well be what keeps that sun from eating you alive.

I’ve come on this trip to witness a vanishing. A human-caused disappearance of these very ponderosa trees—and hundreds of millions more, from New Mexico to California. Starved of water and then taken down by insects and disease, or burned into oblivion by repeated, abnormally intense wildfires, much of what is now ponderosa forest is turning into permanent grasslands and shrublands. Even before the devastating droughts of the early 2000s, fire ecologists declared that the speed at which forests were disappearing in the region to be nearly unprecedented; and, at the same time, that the size of high-severity burns in Southwestern ponderosa pine forests were the worst since the start of the modern climate era, some nine thousand years ago. “Even under the most optimistic estimates of natural regeneration,” wrote researchers in Fire Ecology, “large high-severity fire patches are likely to remain without forest cover for many decades to centuries.”

One study in the prestigious journal Nature Climate Change predicted that 72 percent of all evergreen forests in the Southwest could die off by 2050, with many more likely to disappear by the end of the century. Here, then, could well be the first post–climate change landscape in America. In 2003, about the time droughts and wildfires were beginning to pile up in the West, Australian philosopher Glenn Albrecht coined the word solastalgia. Melding the Latin for “comfort” with the word for “pain,” it speaks to what Albrecht saw as a kind of homesickness. A deep unease born out of the sense that one’s home landscape is unraveling. This fifteen-hundred-mile journey is an attempt to better understand how such an unraveling came to happen in

the American Southwest. What could we have done differently? What can we do now? Also, given the extraordinary aesthetic appeal of these forests—the love affair they’ve sparked in millions—what will be the shape of the hole in our hearts when they’ve gone?

I’ll begin the search for answers to those questions in the ponderosa strongholds of northern New Mexico and Arizona. Then I’ll head off to the northwest, into this canyon country of Utah—a region where the tree can show up either as part of a sprawling village or as a solitary giant in the bottom of some stony canyon. Finally I’ll roll west into the legendary forests of the Sierras where, in just the past twenty years, some two hundred million conifers—a great many of them big ponderosa—have already been lost.

Of course when we talk about the forest, we’re never really just talking about trees. Disappearing along with the ponderosa are pairs of goshawks, those extraordinary birds found twisting above the canopy in early summer on their legendary sky dances and, while hunting, spinning low around the tree trunks like jet planes in a Pixar movie. Fading, too, is the fluty drumming of Grace’s warblers and the hammering of the white-headed woodpecker. The dusky grouse, as well, along with great horned and flammulated and Mexican spotted owls. And then there’s the red-tailed hawk and the eagle, sitting in the tops of the big ponderosa, in their nests made of broken sticks. Ebbing, too, are the midnight yelps of the red fox, the chattering of tassel-eared squirrels, the trills of bobcats, the grumbles of black bears. Even dead standing ponderosa have long been vital to the community, what with the holes and hollows in their trunks being prized by everything from bluebirds to nuthatches, flickers to woodpeckers. The Southwest without ponderosa is like an orchestra stripped down to a pair of violins and a kettle drum.

“Its dry and spacious groves invite you to camp among them,” wrote the great naturalist Donald Culross Peattie about the ponderosa seventy

years ago. “Its shade is never too thin and never too dense. Its great boles and boughs frame many of the grandest views of snow-capped cones, nostalgic mesas, and all that bring the world to the West’s wide door.” Much like the redwood and sequoia groves of California, mature ponderosa groves sparked awe in both poet and logician. Not just because of the towering stature of individual trees, each wrapped in russet-colored bark and exuding vanilla- or butterscotch-scented perfumes. But also because, in maturity, they form remarkably spacious forests. What’s more, big trees rarely wear branches along the first twenty or thirty feet of their trunks; that yields a woodland with sprawling views, the trees fading in the distance into a soft wash of shadows. These aren’t the old woods of befuddlement, with waist-deep understories of bugs and brambles—the kind of place Red Riding Hood goes afoul, where the fiends of fairy tales wait for hapless children. Quite the opposite. Here is a forest full of welcome, one that puts its arms around you and lets you breathe. The tree equivalent of a big yellow lab waiting on the front porch, eager to welcome you home at the end of a long day.

Some anthropologists have pointed out that much of the landscape art we’ve tended to fall for over the centuries tends to mimic qualities of those places where hominins first started walking exclusively on two legs— open, well-lit clusters of trees rising along aprons of grass. The ponderosa is that forest. Maybe the fondness we feel lies deep in the bones.

There are two culprits behind the disappearance of ponderosa in the Southwest. One is climate change. The heat and prolonged drought that have been smothering these lands over the past thirty years can either kill trees outright or, more commonly, weaken them so much they become easy prey for tree-boring insects and mistletoe and blight.

The other culprit, though, has to do with a disastrous choice we made early in the twentieth century—and then leaned into for nearly seventy years—which was to suppress all wildfires. There’s much to say about how essential fire is to the forest. For now, though, suffice it to say that in the arid West, fallen trees and branches and other natural

debris are cleared away only by wildfire. Put all those fires out, and the debris—often referred to as the fuel load—gets thicker and deeper, until what would’ve been a healthy, necessary burn becomes a hellish conflagration. Today there are about three hundred million acres of land in the West with unnaturally heavy fuel loads, which is about three times the size of California.

Even under the most favorable climate conditions, the arid Southwest has for thousands of years been a sparsely decorated landscape, showing little of the tree diversity found in the eastern United States or the Pacific Northwest. In the early twentieth century, back in the woods of the East, it was heartbreaking to watch the mighty chestnut fall to blight and devastating, not long after that, to see the collapse of the American elm. But even with those losses, the birds and bears and bugs—and we humans, too—could, each in our own way, keep feasting, literally and figuratively, on the white oaks and red oaks and sweet birch and black locust and sycamore and beech and white ash and tulip trees and hemlocks and white pines.

These western lands have no such bench. Most large pines—and the West is largely a land of pines—live in places with more moisture. In many drier stretches of the region, only the ponderosa has figured out how to thrive to the point of becoming a towering presence. It has an amazing ability to put down deep tap roots in its first year of life, up to two feet long, touching what little water there may be; later, as an adult, it can reach down thirty feet. Add to that its uncanny ability to conserve water by closing the pores of its needles (the tree is roughly four times more water-efficient than a Douglas-fir), as well as the superpower of seedlings able to withstand temperatures of over 150 degrees, and you end up with a tree—the one tree—able to live the bravura of a truly vertical life.

•

For a lot of beings on planet Earth, these are excruciating times. We’re increasingly being knocked about in a landslide of drought and fire and

6 The Twilight Forest

floods and hurricanes and rising sea levels, which even under the best scenario—and at the moment best scenarios have been yanked off the table—will keep us reeling for decades, if not centuries, to come. Like a lot of people, in more anxious moments, I find myself just wanting to escape, forget it all for a while. But sooner or later, I always come back to the urge to pick even one of these thousand doors of loss, pull it open, and walk through. It’s not a move without sadness and grief. But embracing the things that are going away also brings riches—the kind of gift that always comes when we stop to honor what we care for most.

This particular doorway is an especially personal one. From the time I was twenty until well into my sixties, the research I did as a conservation writer brought opportunities to spend thousands of miles hiking up remote trails under a backpack—or sometimes, crossing landscapes bereft of any trails at all. It was often the ponderosa that sheltered me when hard weather hit the fan, offering places to hunker down in hurling wind or rain or hail or snow. It offered precious shade, too, on blistering summer afternoons at the bottom of Hells Canyon, or the Chisos Mountains of west Texas, or the sunbaked rocks of Nevada’s Spring Mountains.

Yet beyond all that, it was to the ponderosa groves that I went to mourn the biggest losses of my life. My father dying on a construction site when I was twenty-four. My mother, from cancer, when I was thirty-one. My first wife, lost to drowning in a cold Canadian river two weeks past her fiftieth birthday. These were the forests that showed me what it means to have nature hold you. Offering much-needed peace, to be sure. But beyond peace, a feeling of being sheltered—a sense that even when the world is dark, there are places you can go to feel some measure of belonging. Plenty of landscapes have thrilled me over the years: the summits of big mountains; the fast, roiling bellies of Arctic rivers. But when the matter at hand was to salvage myself, nothing suited me like ponderosa.

There was a famous writer born in my hometown by the name of Kenneth Rexroth; often he’s been referred to as the father of the Beat

poets. Living in the Midwest into his teen years, Rexroth once wrote about waking up one morning and feeling utterly forlorn. For months he’d been out scouring the landscape, hoping to find some kind of inspiration he could use to weave new, more dynamic stories for his generation—something to match “the way of the gods and goddesses and heroes and demigods of the ancient world.” But look as he might, out there among the factories and cornfields, he couldn’t find it. With the buzz and whim of such myth gone from our lives, Rexroth warned, we’d mostly be left with a gnawing hunger to consume. It was time for Americans to reinvent themselves, he concluded. And that would take reimagining our relationship with nature.

Rexroth eventually packed his bags and headed west, spending his first summer sitting alone in a fire tower above the ponderosa forests of western Montana, writing poetry and watching for smoke. When I was twenty, I went west, too, as I’d told my parents I would when I was nine years old. West to the magnificent mountains, to the whitewater, to the big runs of Douglas-fir and lodgepole pine and ponderosa.

Today when I see the skeletons of the former ponderosa forests— a smattering of bare gray trunks, starved of water or killed by pine beetles, the few remaining green ones standing on point like exhausted soldiers holding vigil for fallen comrades, deep down I feel a kind of primal flinch. It brings to mind a line by poet Jane Hirschfield, written years ago to mark the death of one of her favorite old trees.

“Today, for some, a universe has vanished.”