ON REPAIRING AND RESTORING BOOKS, MANUSCRIPTS, AND PAPERS

WITH DIRECTIONS FOR EASY BINDING AND PAPER-

MENDING—BOOK-WORMS

It happens often enough that some valuable old manuscript or early printed work, if not destroyed as useless, is sold for a trifle because it is torn and worm-eaten or otherwise injured. The loss to literature from this cause has been terrible, and it is all the more so because in most cases it was the result of sheer ignorance.

Paper is a composition of linen, cotton, or other vegetable fibre reduced to powder and then combined with size, which is a kind of glue, paste, or binding medium. Therefore paper can be mended by using, in the soft, macerated, or pasty form, paperitself—which very simple fact appears to have been hitherto a secret from the greater portion of mankind. That is to say, having a piece of paper with a small round hole in it—looking as if some one had fired a shot through it—take another piece of paper of the same quality and reduce some of it to a very fine powder or mash it fine with a knife, combine it with good flour-paste infused with a little clear white glue, and make a soft paste with the powder; then, laying a porcelain tile or piece of tin under the sheet, with a hole in it, to prevent sticking, spread the paste, which is really soft paper, with a knife over the hole. When dry it will be mended permanently. Observe that the pulp must be a fine paste, not merely paper mixed with paste—i.e., lumpy and stringy, but soft. Secondly, that a better

“binder” or size than flour-paste is one made from scraps of parchment boiled, till all the gelatine is extracted. Take the latter and let it boil till thick. It makes a finely glazed surface.

Do not begin to do this with a book, but with a sheet out of which holes have been punched. It is delicate work, and you must not expect to succeed in it at once. But in time, with care, you will remake the paper with great skill. There are workmen who can even reunite torn edges in this manner so that the mending is almost imperceptible. This is remaking paper with paper. In some cases it will suffice to simply neatly paste a piece of paper over a torn-away space. This may be done—as in most cases—very clumsily, or it may be performed artistically and daintily. In the latter case, using a very sharp and specially thin bladed penknife, shave down or scrape away the overlapping edge, and apply the paste sparingly with the point of a camel’s-hair small brush. Before it is quite dry lay the leaf on a smooth, hard surface, and with the penknife or a burnisher flatten down the thinned edge to an uniform surface. This also requires a little practice, but when learned the artist may effect miracles of restoration. One may, and that not infrequently, buy for shillings books which when mended sell for many pounds.

It often happens that we find some curious little old book which has been sadly cut or worn, almost down to the type. Take it, and with a flat rule carefully cut out every page, leaving just a little rim of margin. Then having obtained old paper corresponding to your text, or good modern hand-made Dutch, using strong glue-paste or flour and gum-arabic, or paper-paste, make borders, on which paste the old pages. If you have old paper—there are dealers who can supply it—you may do this so well that the juncture will be hardly perceptible. In any case you will greatly enhance the value of the book. In this, as in all such work, never attempt to restore anything of value till you shall have succeeded by experimenting. This is very seldom done, and yet books thus restored sell for a price which must make the work very profitable. One reason, however, why we see so

little of it is the extravagant price charged for all such work by the agent who supplies it.

The prices paid for books thus restored and mounted are extremely high, simply because there are so few people who know how to do it well; and yet, as any of my readers may find, the art is an easy one, requiring only neatness and care. There are very few libraries where such restorers might not be employed, to the very great profit of the collection. All purchasers for libraries are continually rejecting books because they are tattered and worn or “holey,” which could be sent to the hospital and doctored into value. And it is, indeed, to be regretted for the sake of the public that our great libraries have not all shops attached where duplicates and damaged rarities restored could be sold at fair, not fancy, prices. For it is firstly the great librarian who sees and rejects the most books, and who could do an immense amount of good, and greatly stimulate an interest in collection and literature—and make money—if he would also facilitate acquisition. The art of restoring and of mending is as yet so much in its infancy, and is so little understood and practised, that there is not one book in a thousand, even of rariora and curiosa, preserved as it might be.

It may be worth while to lay some stress on the fact that many persons, especially women, if they will take a little pains to experiment, can easily make a living by thus restoring books and injured documents. There are, indeed, many other means of earning money indicated in this work.

A CHEAP AND DURABLE VARNISH specially made for bookbinders is prepared as follows:—Take coarsely powdered gum-copal, add to it oil of thyme (oleum thymi serpilli) or pure oil of rosemary (oleum rosmarini), sufficient to form a solution. Pour off the superfluous liquid, and mix the remainder with sufficient alcohol to dissolve it well. In making take only so much of the oil of thyme or rosemary as will cover the copal, and of alcohol about eight or ten parts to the whole. Special varnishes, and perhaps better, are known to many

bookbinders, who will sell them, or inform you where to obtain them. I know of none so good as that of SOEHNÉE, which is, however, very expensive, costing about ninepence per ounce. It is rather brittle, however, for pictures.

When a book is dog’s-eared, or its leaves have been turned, if the paper be of a thin, poor quality, its chances of restoration are better than if it were good and stiff. In the former case damp the leaves one by one with water in which a little gum tragacanth has been infused. This is not so much an adhesive as a mere stiffener, and is used as such for laces. Then flatten them, putting a piece of smooth white paper between every leaf.

There is, I fear, nothing to be done where the reader is so utterly devoid of all the instincts of a gentleman or a lady as to turn over a stiff, thick, highly glazed paper to mark the place! I have just found this done in a magnificently illustrated work from a circulating library, and, to aggravate the offence, it was on pictured pages! I would here remark that if every reader would keep by him a piece of indiarubber or eraser, and obliterate, or at least render illegible, all the scribblings made on margins, this detestably vulgar practice would soon be at an end.

It may be observed that to repair pages which have been torn across, or engravings, the rent is usually transverse—that is, such as to leave a small flap edge. If we take very strong gum in very minute quantity on the point of a camel’s-hair brush, we may often succeed with great care in perfectly reuniting the edges. Observe that in this, as in everything, the mender should not draw his conclusions from the first effort, which will probably be a failure, but from frequent careful observation and experiment. There are marvellously few people in the world who take the pains to become really good menders of anything—excepting lace and the like—hence there are few things mended at all except by botchers and amateurs.

INK-STAINS can be removed from paper by laying underneath the blot a pad of clean blotting-paper or fine muslin. Take a fine sponge, dip it in lemon-juice, and press it gently on the stain, so as to moisten it. Then with a clean, white, soft rag, folded into a pad, press on the spot, and the pad, lifted off, will remove a little of the ink. Repeat this process a few times, taking care to change the pad in your hand every time toa cleanspot. Do not try to rubthe stain out (as most people do), but to draw the ink away or out by sucking up or by absorption. If you simply rub or press the ink in again which has just been drawn out, you will only make bad worse. And here I would observe that by this process of pressing, absorbing, and changing the “sucker” applied, you can draw appalling stains out of almost anything. You cannot, of course, prevent chemical action or change of colour, but in most cases this is the best process.

It is better to begin with lemon-juice and a little salt and water where the paper is thin. When it is strong, a mixture of muriatic acid and water generally extracts ink.

In a great many cases the staining fluid can be drawn out by absorption before any chemical change in the colour of the stuff can have been effected. Therefore it is all-important to know how to do this yourself at once, and not wait till it can be sent to a dyer or scourer or cleaner. In a few hours’ time that which could have been promptly extracted will be past all cure. When you spill ink on paper, promptly apply, first of all, blotting-paper, and then try absorption. If any stain remains then, apply the acid.

TO TAKE OUT A GREASE-SPOT.—Heat an iron (I generally effect it with a burning cigar), and hold it as near as possible to the stain without burning the paper. If this be well done the grease, wax, &c., will rapidly disappear. If there are any traces left, place on it powdered calcined magnesia for a time. This is also a good means to extract grease, wax, or oil from cloth. Very often, where lemon-juice or acid would ruin the colour of a cloth or other fabric, chloroform will take out the spot and leave the colour unchanged.

Bone, well calcined and powdered, is an excellent absorbent of grease. It should be remembered that all such processes must be renewed, for after the powder or cloth applied has received a certain quantity of the grease or stain, it ceases to be taken in. A gentle pressure or rubbing, after laying paper over the powder, facilitates the absorption.

The celebrated ATHANASIUS KIRCHER, who wrote in the sixteenth century, has left an amusing account of how he one night, stopping at a convent in Sicily, took a book from the library (it was STEPHANUS

FAGUNDEZ’ In Præcep’a Ecclesiæ)—“a new book and elegantly bound”—and spilt over it and in it all the midnight oil from his lamp! In great alarm he sent for quicklime, but there was none to be had. So he bade the monks bring him some bones, which he quickly calcined and pulverised and applied. And the next morning there was not a trace of a spot, only a little smell of oil, which soon vanished. He adds, that plaster of Paris would have done as well.

Ascertain carefully the nature of the spot before trying to extract it. For resinous substances use spirits, or eau de cologne, or turpentine. Benzine extracts several substances.

An old recipe for removing ink-stains was to take a spoonful of good aquafortis, in which break a piece of chalk the size of a large barley corn; add two spoonfuls of rose-water and one of vinegar. This should be mixed in a clean glass and left to stand for several hours. It is to be applied with a piece of new sponge, by pressure, and not too freely nor too long. When the paper is nearly dry renew the process, and when the ink shall have disappeared, promptly wash out the acid with pure water and a clean linen rag. (But it is too strongfor many fabrics.)

When the ink does not penetrate the paper it can be removed by erasure with a sharp penknife, or a preparation of vulcanised indiarubber and powdered pumice-stone sold by most stationers. When this latter does not “bite,” its action can be aided by very

slightly moistening it. After erasure rub the spot scraped with very finely powdered pumice-stone, and polish with a burnisher or any smooth substance.

Even when an inkstand has been spilled over a printed or longwritten page, we can by prompt action extract the new ink and leave the old plain as ever; but the reader who expects to work this miracle of changing night into day must not wait till the accident happens to first attempt to remedy it, or he will probably fail. Let him first of all, not once but often, pour ink on some waste and worthless page, and then experiment first with the blotting-paper, then with the dilute acids and the padding. The time will not by any means be wasted.

A fresh ink-spot can be easily removed from paper by rubbing it with a finely pulverised mixture of saltpetre, sulphur, alum, and pumice. If the spot is an old one, moisten it first a little with water.

Ink-spots, &c., in old MSS. were sometimes ingeniously covered by ornaments in gold or colour.

When an entire page or many pages of a book are missing, it often happens that, at much less expense than would be supposed, an ingenious printer can restore the whole. There are many books for which it would be worth while to have the type cast, for even with a page thus restored the book may be worth ten times as much as if it were wanting. Missing pages are often supplied by photographic facsimiles from another copy.

It was only yesterday, as I write, here in Florence, that I heard a tourist declare that there was nothing worth buying to be found, and that everything curious was snapped up at once. To which I could not assent, never having seen so many objects as of late which I regarded as great bargains. But they were all dilapidated, and the tourist generally likes to see everything in splendid condition. To him who can restore old books and ivories and leather-work and panel

pictures, there will be no lack of bargains for a long time anywhere. The men who sell are not all such marvellous experts in mending up, repairing, and forging as literary dealers in the wonderful would have us believe. If they were so clever they would not let valuable panel pictures split in two before their eyes from ignorance of knowing how to straighten and tack them at a penny’s cost. There is abundance of clever forging, of lying ivories and silver-work and sham antique leather, but of restoration of smaller or of single objects there is very little; and there is, as I have said, in this a vast field for every collector who knows enough to make practical application of what is taught in this book. It is so far from true that everything is now snapped up, that I confidently assert that there is hardly a bric-à-bracshop in Europe in which a skilled repairer cannot find a bargain, and in most cases several.

It will often be of service to the mender of books to be able to prepare parchment-paper for himself. If we take a mixture of one part nitric acid to three of water—the proportions varying very much with the quality of the acid and of the paper and dip into it a piece of soft unglazed paper, the latter will at once harden into a substance like parchment. It should be at once washed in changes of pure water. I may here observe that neither in making this nor anything else should the operator be satisfied with a single experiment.

Regarding paper, there are certain curious facts worth knowing by every reader. Before the invention or general use of window-glass, a very transparent kind of paper was, according to KIRCHER (De Secretis), prepared as follows:—

Take paper from the mill, not as yet sized, and mix with it to six parts of turpentine two of mastic. This really makes a very clear, or at least diaphanous, medium, which may be used for temporarily repairing broken glass windows.

The same writer informs us that if we take fine parchment (pergamenam hædinum), prepared without lime, or naturally dried, we should lay it in water, which will just cover it, in which has been well infused boiled honey and the white of eggs. This was used to repair coloured glass windows.

There is also given in the Zauberbuch of JOHANN WALLBERGER, Frankfort, 1760, a recipe for the same purpose:

“Take parchment prepared without lime, and steep it in a mixture of thick gum-arabic dissolved in water, the yolk of eggs well shaken, and clarified honey.”

It is worth observing, as regards these recipes from old works, that while those founded on modern chemistry and experiment are generally cheaper and apparently better, the former are often more durable in effect, and were, indeed, more thoroughly tested. There were a great many parchment windows in those days, and there are none now. And in these old works of PORTA, WECKERUS, TENZELIUS, KIRCHER, ALEXANDER OF PIEDMONT, MIZALDUS, VALENTINE KRAUTEMANN, and many more of which I have a large collection, there are many curious prescriptions, many of which I have seen revived from time to time of late years as modern scientific inventions—on which subject an interesting article could be written.

A weak solution of oxalic acid in water is often the best to remove ink and other stains from strong white paper or linen. It should be applied by gently pressing or dabbing (not rubbing) with a cotton pad. As soon as the stain is removed, dab it again with clean water. Take good care, however, that there are no scratches or cuts on your fingers, for if the acid gets into them it will cause great pain.

I may here mention that the old bookbinders’ paste was made as follows:

Take a quarter of a pound of starch, steep it a quarter of an hour in water, and stir it till it is milky. Add a pinch of alum, and boil it once

more.

This was said to keep better than paste made from flour. (Add a few drops of oil of cloves or carbolic acid, and it will keep very well.) Flour can, however, be used instead of starch, and a good adhesive be the result. A little glue very much improves it. There is a great difference in the quality of cement made from bread, as the condition of the latter has been changed by fermentation.

BINDING.—Repairing books is nearly allied to binding, and the latter is, in perfection, a somewhat difficult art. Yet it is not at all difficult for a careful person to bind up many works in such a manner that they will bear much reading, and with a little artistic skill look very well. This may be effected as follows:—

When a book is stitched together, there are sewed into the back two or more cross pieces of string or strips of muslin, which project a little on either side, and which, by being pasted down inside the cover under a leaf, hold the book and cover together. This is further strengthened sometimes by another strip of muslin. When the back is firmly gummed or pasted to the book, so as to bend with it, it is called a flexible back, which also adds to the strength of the whole.

If the reader will now take a simply sewn or stitched book, without binding, and will place across its back two or more strips of parchment, and glue them on with the strongest possible cement—mastic being the best, but acidulated glue or flour-paste with glue, or even dextrinepaste, will answer the purpose—and if he will again paste up and down over these a strip just the width of the back, he will have all that is necessary to make a strong binding, for this will hold as well as the strings. Note that the parchment strips must first be thoroughly wet through and macerated, or crumpled till quite soft. Again, that when the paste is nearly dry the strip should be rubbed in.

Next cut out two pieces of strong pasteboard, each a very little larger than the length and width of the book. These are the covers.

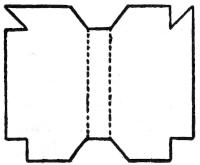

Now paste the outside of the straps exactly to the inside of the covers, leaving just enough space for opening and closing. When dry, the book should open and close easily. Then take the outer cover of leather or cloth, which is cut in the shape indicated in the accompanying outline, paste it well over the back, and then turn the edges over and paste them down over the cover inside, so as to form a narrow margin, as may be seen by examining any book. Also turn down, before doing this, the edges at the ends of the book. The binding will be much stronger if, after pasting the ends of the parchment strips to the covers, we paste over them in turn good, strong pieces of paper, close to the back, to prevent the strips from pulling up.

If there be fly or blank leaves on the sides of the book, paste one of each down over the inside of the cover. This will conceal the margin and add greatly to the strength of the book. But if there be none, you can supply them, firstly, by a method which will make your binding even stronger than that of most books. Take a very strong piece, let us say, of Whatman’s or any other good tough linen drawing-paper, just of the size to cover the whole book—that is, back and sides. Cut in it four slits, and pass the strips which are to bind the book to the cover through, and gum them down, and then paste the fly-leaf thus added down over the strips. But it will answer every purpose if you simply gum fly-leaves on by a very narrow margin of “adhesive.” All of this will become clear to any one who will carefully examine a book. And anybody who has the dexterity to fold a letter neatly or do up a parcel properly, can in a short time, after one or two experiments, succeed in binding a book in this manner. I have observed that those who fail as amateur bookbinders generally do so because they attempt too much too soon, and aim at

producing elegant masterpieces before they have learned to manage with ease such common work as I have described.

Though this manner of strip-binding is little known, it was, strange to say, the very first ever practised; for, according to OLYMPIODORUS, one PHILATIUS was the first who taught the use of glue to fasten written or blank leaves together, for which great discovery a statue was erected to him. Binders were called among the Romans ligatores, as they are still in Italy, legatori; and it was here, indeed, that I myself learned the craft, as I now generally bind my own books. Those who prepared and sold the covers for Roman booksellers were called scrutarii.

There is a very easy way to bind up pamphlets, MSS., or letters when they have any margin for a back. If you cannot have them stitched—which, though difficult to an inexpert, can be done for a mere trifle—then sew them together across from side to side. Where the pages are of great value, gum them together by a very narrow doubled or folded strip of adhesive. This done, bind as before, or else simply paste on a cover of drawing-paper at the back, and the fly-leaves to the sides. A great deal of loose literature, flying leaves, clippings from newspapers, letters, &c., can in this way, at no great expenditure of time or money, be converted into really valuable books.

I may here observe that cloth for binding, thin leather, and even common parchment or parchment-paper, are much cheaper than would be supposed, and that the average cost, all expenses included, of binding a duodecimo book in these would only be from threepence to a shilling. Any waste parchment will serve for binding.

Any person, however, who can emboss leather with tracer and stamp, even though but a little, after a week’s practice, can decorate and ornament books so as to greatly enhance their value. Nor do I exaggerate when I say that here is a field in which any person who can draw or copy decorative patterns moderately well might make a

living. The reader will find the fullest details as to how this is done in my Manual of Leather Work. (Price 5s. London, Whittaker & Co., 2 White Hart Street, E.C.) In the present work I can only state that it is executed as follows:—Bind your book with cardboard in fairly thick, hard, and firm brown leather; there is a kind made for the purpose in Germany. Draw the pattern on it, or else draw it on paper with a crayon-pencil, and rub it from the back on the leather. This done, go over it with the fine point of a miniature brush in Indian ink. Dampen the leather slightly as you work with a sponge, and mark the outline with a tracer and stamp the ground with a matt. You may leave it brown, but if the work be coarse, I advise painting the whole with ink or Indian ink, and then coating it with SOEHNÉE’S varnish, No. 3. Rub this down well by hand.

If you can supply the design (which should always be bold and simple), any wood-carver will, for a few shillings, execute it in intaglio on a block of wood, which should be at least one inch in thickness, and also have a transverse piece screwed to its back to prevent its warping. With this you can stamp off as many covers as you want. Retouch them by hand with tracer and stamp. If blackened, and then touched up with gilding and varnished, such books are very attractive, and should sell well. Any person who can design, or even trace, a pattern can have it cut on a block for a few shillings, and anybody having such a block can print off any number of impressions in damp leather, and retouch them with stamp and tracer, and glue them to cardboard covers, for books or albums, and sell them at a good profit. Yet, though this has been clearly set forth by me several times in manuals, &c., I have never yet met with a single amateur who has attempted it. There is as a rule far more suffering in this world from laziness, inertness, and an indisposition to tryto do something than from any other contaminating influences which lead to poverty.

When a book is even woefully dilapidated, so that there is no margin to stitch, do not despair. First separate every leaf, smooth it, and, if necessary, dampen it with a slight infusion of tragacanth. Then, if

there is even the twentieth part of an inch of margin left, take strips of good, tough, thin paper, and with care stitch the leaves to these strips. For some severe cases you must use very thin transparent or tracing paper to gum over the text, but which must be visible through it. This, if neatly done, does not look so badly as it would seem. If one strip be folded and used to connect two leaves, the stitching and binding become easy. I have already described how to restore margins and fill worm-holes.

I think that if any person of literary habits will consider all that is written in this chapter, and will begin to practise it with deliberation and care, he will surely succeed, and find it a very profitable and agreeable occupation. All of such men have pamphlets, MSS., autographs, letters, newspaper clippings, and papers, which, if classed and made up into book-form, would be more available for use, and far more valuable. I say nothing of repairing old books; it speaks for itself as an easy and lucrative employment. And it may be observed that a young man who can thus bind and repair would make a most valuable assistant-librarian, though the business can be mastered very soon indeed; and it would often happen that in choosing a secretary, where there are many papers to file or a library to look after, or an assistant in an antiquarian book-shop— particularly the latter—preference would be given to one who had mastered practically what is taught in this chapter. And as on board ship the best sailor is generally the best mender—every old tar being proverbially skilled in repairing and having a quick eye for emergencies, even on shore—so the one who can rehabilitate and “form” books will probably be a good assistant in all things.

It may often happen to a writer or copyist that he has occasion to erase a word, and cannot write over the space lest the ink should spread. In old times this was remedied as follows:—A very little juniper gum, levigated to the finest powder, was rubbed over the spot with a soft linen rag.

In all kinds of repairing or technical work it is sometimes necessary to draw circles when the artist has no compasses. Yet this can be done to perfection, almost by free-hand, and very easily. Take several sheets of paper or a blotter; lay on it the piece to be drawn on. Take a pencil in the fingers, as is usual, rest the hand on the nail of the little finger as a point—having previously pulled the sleeve of his coat well up, so as to get a full view and then with the left hand draw or revolve the paper. In most cases a perfect circle will be the result. This is admirable practice for learning to draw circles entirely by free hand, as may be found by experiment.

Paper can be made, if not absolutely fire-proof, at least deprived of inflammability, by being steeped in alum-water, or in oleum tartari per deliquium, or oil of tartar. Stationers might find a sale for such paper. If the document which was thrown by a certain Duchess into the fire had been thus prepared, it might have been rescued by a bystander before it perished.

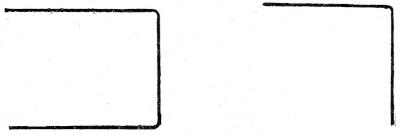

The art of preservation, or prevention of injury, is allied to restoration, for which reason it would be well if more people who send books by mail would use protecting corners, which can readily be made by anybody with a pair of strong scissors from thin sheet brass, tin, or iron. Take a piece of metal of a rectangular shape, as follows:

Then double it into a triangle over a piece of cardboard, or of wood, exactly the thickness of the cover of the book:

Very valuable books should be kept in boxes of thin metal, especially in India. Such cases should not be made to open and shut with a hinged lid, but with a covering, and like a cigar case. Such cases, or at least metallic guards, should also be used when a book is wrapped and tied in the usual manner and sent by mail. I am quite sure that at least every other book which I have received by mail during the past year has shown on its edges melancholy scars from its strings, reminding one of the wounds which the heroic red Indian retained from his bonds. A guard is simply a piece of sheet-metal, bent as follows, once or twice:—

These guards are invaluable for packing books in trunks. Their price is trifling, and in the end there would be great economy in using them. Books should not be packed very tightly together on their shelves. It bursts the binding, especially of modern works in boards and paper. The old parchment flexible bindings were in every respect better, and they could even now be made far more cheaply than is generally supposed to be possible. I have before me a book nearly three hundred years old, bound in skiver parchment (split, or very thin), which has evidently been much used, yet which is still in good

condition. But parchment need not be prepared very carefully for ordinary binding, and it could be sold for half the price charged by law stationers for what is used to write on. In the United States one must pay much more for a sheepskin than for a sheep, indeed in some cases three or four times as much—that is to say, the skin as a parchment in New York costs as much as three sheep in the Far West and yet the expense of bringing the skin to the East and of tanning it are in no proportion whatever to the stationer’s profits.

Any one who will examine an ordinary old parchment-bound book, such as lies before me, will see at a glance why it must be more durable than a modern binding. In the modern book the stiff back rises full to the edge, or generally abovethe level of the sides, and is made of muslin, paper, or at best of soft leather. Therefore in time it breaks from pressure and friction, or wears away. The parchment or vellum had in most cases this back-edge put back or kept down as much as possible, and the tough covering was all in one piece. It is very true that it is not possible to obtain plain, old-fashioned parchment now, and that those who would have vellum, or even sheep, must pay an enormous price for it. This would not, however, be the case long if there were as great a popular demand for parchment binding as there now is for flimsy muslin. Those who prefer the former will find no difficulty in having it made for them, and in binding their books themselves according to the directions which I have given.

I shall in the chapter on Papier-mâché show how covers for books may be cheaply made at no great expense, which may be beautifully embossed and are extremely durable. This is, briefly, by having a flat mould or die, on which lay alternate coats of paper and firm paste (into which glue and alum enter), then passing over them a breadroller, continually adding paste and paper till the whole is complete. When finished, rub in black or any other colour, then rub in oil, rub again, apply SOEHNÉE, No. 3, and finally rub by hand. This will make very beautiful binding.

It is much to be regretted that, although there has been of late years, owing to machinery and patent processes, such immense production of cheap and showy binding, as shown in photograph albums, there has been as steady and rapid decrease in quality, strength, and durability. It is becoming unusual, even in very expensive books, to find one which can be honestly and well opened or is well stitched. I have, since writing that last word, tested it with two books recently published, one costing six shillings, the other a guinea. The latter was fairly well put together and “held,” but was warped in the stitching and pasting. It was “bad work.” As for the six shilling book, it cracked clear through to the back at every page which I opened, and yet I did not open it very widely. I should say that any amateur who could not learn to bind books better in a month or six weeks than these were bound must be stupid indeed. The examination of a number of other books shows that what I have said is now generally true, and that even very expensive and pretentiously elegant works are not half so well bound in reality as were common and cheap school-books two hundred years ago. This I have also confirmed by examining a number of the latter bound in parchment, which bid fair to last for centuries to come.

Should this cheap, trashy, and showy style of binding continue, and with it a constant rise in the price of everything made by hand, the result will be that everything durable will be made by “amateurs”— that is, by people who to artistic spirit unite a certain personal independence. Owners of libraries will bind their own books, or else employ people who will work as artists, and not like mere machines. The vulgar and ignorant will continue to buy showy, cheap duplicates —induced by hearing, “’Ere’s an harticle, mum, that we’re sellin’ a great many hof”—while the cultured will prefer the hand-made, which is not necessarily more expensive. In fact, if the unemployed in England—or the victims of the wholesale steam trash-maker— could be taught easy hand-work, as they all can be, it would be possible to not only vastly relieve national poverty, but we could have a variety of articles of better quality. For it appears to be, by some strange law, a fact that, with all the improvements in

machinery, men can still make by hand—and well—pictures, clothes, shoes or boots, bookbindings, and works of art generally—that is to say, anything in which skill or character can be shown; while, on the contrary, in all such matters machinery, instead of making any progress, is, owing to competition, actually falling behind! Scientific and other journals are continually boasting of new discoveries and improvements, but despite this the jerry-built houses of threefourths of London, the sawed and glued cheap and vile furniture (made by scientific steam) with which they are filled, the average quality of everything into which skill and taste are supposed to enter, show that this boasted “end of the century” is also rapidly coming to an end in good taste and the quality of its work.

He who will learn to mend with care, taste, and skill, firstly his books, will find that to progress from this to binding and to making elegant covers is only going from A to B. The binding of the olden time, while it was incredibly strong, vigorous, and quaint, was extremely easy to make, as I have satisfied myself by much examination and personal practice. The stitching was not with the weakest and cheapest cotton-thread; still less was it with wires too thin for the purpose; it was executed with linen pack-thread, from thetoptothebottomofthepage, in three or four stitches, so that the book could really be opened and bent back till the covers touched without injury to it. All of which could be given to-day with the parchment covers at the same price which the book now costs, and to pay the same profit, were it not that public “taste” prefers showy trash. Beyond good, strong stitching, all the necessary process of binding is very easy. It requires neatness and care, and some practice, but it is decidedly not difficult. He who has mastered it will find that other kinds of mending, and also the practice of allied minor arts, are simply the succeeding letters of the alphabet.

It is a fact, to which I invite attention, that dilettante amateurs of books invariably understand by binding nothing more than its refinements and easily ruined adornment, which books had better be without. Amateurs of this class always attempt at once the most

difficult work, and generally fail. As a rule, almost without exception, the prize specimens of modern binding seen at exhibitions are chiefly remarkable for ornament, which will not endure handling or rubbing, such as surface-gilding.

Pamphlets or letters, &c., can be bound with “eyelets,” and the clamp or punch which is sold with them. Or they may be simply gummed together, in which case use the powerful fish-glue, which holds perfectly.

The easiest and most effective method of side-binding, or where leaves are held together by passing the tie through from side to side, is as follows:—Have by you strips of metal, say sheet-tin, onefourth or one-third of an inch in breadth; also small rivets or tacks. Take two strips of the same length as the pamphlet or papers to be bound, and strike holes in them with a brad-awl and hammer, on a solid piece of wood, at regular distances. Then place these strips on the book, and drive the rivets through the holes. Turn the whole round, and laying the other side on an anvil or a reversed flat-iron, flatten the points of the rivets so that they will hold. Any old tins, such as are thrown away in such numbers, can be made to supply strips. A strip of parchment or strong paper bent over to form a back can then be pasted over the strips to improve the appearance of the volume. Any tinman will, for a trifle, supply these strips and punch the holes neatly for use. They should be found in every library, and ought to be in every stationer’s. It may be observed that in inserting the rivets or tacks you should place them alternately, one on one side and one on the other. A lighter form of this binding is to take a flat-headed drawing-pin, similar to those used by artists, and have a round, flat tin or brass disc, like a thin sixpence or threepenny-bit, corresponding to it. In the latter punch a small hole, and rivet as before. Tinmen will also punch these discs; in fact, they often throw away a great many cut from certain kinds of work.

Where the leader may have a great number of books to bind, he will find it an economy or a means to secure good work to hire a girl

who is an experienced book-stitcher to come and work for him. He can thus be sureof having his works wellsewed from top to bottom with strongest linen-thread in ancient style, instead of their being shabbily wired (and all wiring is shabby, since the thin does not hold, and the thick bursts the binding), or still more shabbily looped together with weak cotton-thread. This effected, he can easily do his own binding. He may not rival a Grolier, or turn out such exquisite “gems” as require to be kept in caskets, and are utterly unsuitable for use or reading, and, like most “elegant and unrivalled” modern binding, marvels of tooling and gilding. But he can most assuredly hope to bind strongly in parchment as books were bound in the olden time, and if he chooses to also ornament them with richly stamped leather covers, he can in a short time learn to do the latter, as may be seen in the ManualofLeather-Work.

The great test of excellence in a book is, Can it be freely handled and read without injury? The most careless examination of most books will convince the reader that this test is almost unknown. The exquisitely whitened vellum bindings of Florence and Venice, which are stained almost with the pressure of a lady’s clean finger; the photograph album, so beautifully stamped in leather as thin as blotting-paper, which scratches and wears into shabbiness in a week, if often opened—all the show-pieces of exhibitions will not endure use. And it seems as if, after all the binding of this decade shall have perished, that of the common, cheap books of the seventeenth century will be as good as ever.

A great number of the adhesives and cements mentioned in this book are quite applicable to mending bindings or making paper stick to paper, &c. The following is, however, not only a paste, but also a glaze, and is extensively used as such on labels, boxes, and cards:

Boil borax with water, and work it thoroughly into caseine till it forms a clear, thick, and extremely adhesive cement, which is also much used to varnish leather or muslins.

It is often desirable to have a varnish or glaze for the covers of books, and still more frequently a paste, which will hold very firmly and yet not penetrate, as glue and paste very often do.

To make such a cement, mix heavy solution of warm glue with freshly made starch or flour-paste. Add to this one-fourth part of turpentine and one-fourth of spirits of wine. This excellent cement is applicable to many purposes.

To paper walls wellwe make flour-paste, and to every quart add ten grammes of alum dissolved in hot water. Then wash the wall with glue-water, and cover the paper with the paste. The alum and glue form a combination which is leathery and insoluble, and not only arrests decay, but clings with great force. Most wall-paper put on with common paste decays more or less in time, and becomes simply poisonous.

A STRONG GUM OR ADHESIVE FOR PAPER, CARDBOARD WORK, OR BINDING

:—

Water 50

Unite the two solutions thus formed; pass them through a cloth, so as to fall into a flat mould. When dry, use by dissolving in hot water.

AMERICAN GLAZE FOR POSTAGE-STAMPS:—

Dextrine2

Vinegar 1

Water 5

Alcohol 1

Stamps are, however, very often surreptitiously removed by means of moisture. The following recipe renders this difficult. It consists of two preparations, one of which is applied to the stamp and one to the letter. It is particularly needed in America, where, according to a statement in a newspaper, nearlyone-thirdof all the postage-stamps are removed from letters, cleaned, and used over again.

I. FortheLetter .

Chromic acid

2.5 gr.

Caustic potash 15.0 ” Water 15.0 ”

Sulphuric acid 0.5 ”

Sulphuric copper-oxide of ammonia 30.0 ” Fine paper 4.0 ”

II. OntheStamp.

Sturgeon’s bladder in water 7.0gr. Vinegar 1.0 ”

The chromic acid forms with the glue a substance insoluble in water, which causes the stamp not to yield to moisture. The two should be

kept in two cups, and the letter first smeared with one and the stamp with the other. I have read of a physician who, finding that his postage-stamps were often stolen, adopted the precaution of giving their backs an application of croton-oil, or some similar powerful “anti-thief-matic,” the result of which was great temporary illness in his landlady and her family. For this recipe the reader must apply to a chemist!

EDER’S GUM FOR PHOTOGRAPHS.—Dissolve oxyhydrate of ammonia in vinous acid, to one part of which add twenty of starch-paste.

CEMENT FOR LEATHER OR PAPER IN BINDING BOOKS, &C. Take 1 kilogramme of wheat-flour, and make it to a paste with 20 grammes of finely powdered alum. Boil this till a spoon will stand uptight in it. Cover the cardboard or cover with this, lay the leather or muslin upon it, and then with a roller press one upon the other. Leather should first be damped. Care must be taken that the paste be not too moist; secondly, that it is laid on very evenly and thinly.

Engravings or texts which have had a piece torn out can be restored as follows:

Obtain a photograph from a perfect copy on corresponding paper, then with gum set it in, so as to supply the deficiency.

As the ravages of the Book-wormform an important item in mending books, and as there is always some interest for collectors regarding this much talked of and rarely seen insect, I take the liberty of reproducing from the American Scienceof March 24, 1893, an article on the subject. An appropriate motto for it might be:

“Come hither, boy; we’ll hunt to-day The book-worm, ravening beast of prey.”