Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION

This chapter initially sets out to establish a comprehensive understanding of urban public spaces, laying the groundwork with a precise definition. It emphasizes the concept of socially sustainable spaces, echoing the sentiments of scholar David Sibley. Furthermore, it delves into the intricate relationship between Spitalfields Market’s economic influence and the erosion of its cultural heritage. The chapter also extends this examination to Brick Lane, colloquially known as Banglatown due to its significant Bengali population. Central to this analysis is the preservation of cultural heritage, notably highlighting the repercussions of regeneration projects over time. The initiatives, as explored in a scholarly journal article in this chapter, have seemingly favoured economic interests at the expense of Brick Lane’s cultural value.

Urban public spaces from the perspective of some scholars “are for people to enjoy nature and provide a gathering place for a social event… [and] …improve the quality of the urban environment, promote people exchanges, reminiscent the urban history and culture, as well as to arouse people’s sense of identity and belonging to all.” 2

Consequently, urban public spaces are social spaces (see Figure 1.0) that facilitate interactions among diverse societal groups, providing “social benefits – that is opportunities for people to do things, take part in events and activities or just to be.” 3 (see Figure 2.0 & 2.1) These spaces stimulate the formation of socio-spatial relationships between various community groups. Architects and designers are pivotal in shaping these spaces, creating opportunities for human inhabitation, and defining spatial experiences. The ambience and design of a place can significantly influence people’s emotions, evoking feelings of happiness or melancholy. Urban spaces can vary in form, ranging from public to private, and sometimes contribute to societal exclusion, fostering feelings of alienation among certain members of society. As David Sibley refers to in his book ‘Geographies Of Exclusion,’ “Who is felt to belong and not to belong contributes in an important way to the shaping of social space.” 4 Therefore it is crucial to highlight that spaces should be open to everyone, irrespective of cultural backgrounds. Encouraging the adoption of human-centric design by architects is vital and valuable for society when arriving at decisions and designing these spaces.

In the context of Spitalfields Market, and the impact on its neighbourhood, this essay acknowledges the need to understand the economic impact on the cultural value of the market, area, and its community. There is a need to improve spaces to be more communally valued in terms of maintaining their traditional character and authenticity. Spitalfields Market has evolved into what it is today, a dense commercial hub selling an array of goods at high prices with market stalls and surrounding cafes and restaurants. It has been designed for and operating as a market for many years serving its locally defined communities which have not necessarily been of the same cultural backgrounds 5 throughout different periods in time, and so it is what it is today at the expense of heritage.

This study underscores the pivotal significance of heritage, advocating for its central placement within the decisionmaking frameworks of architects and urban planners. The imperative lies in recognising the potential repercussions on local communities, notably their susceptibility to displacement. An illustrative case is observed within the proximity of Spitalfields Market, particularly evident in the transformation of Brick Lane, a mere seven-minute walk from the market. Over time, the market’s commercialisation and subsequent economic upsurge have arguably detrimentally impacted the surrounding neighbourhood.

Brick Lane historically thrived as a hub for the flourishing Bengali community, characterized by a ‘vibrant street’ 6 (see Figure 5.0, 5.1 & 5.2) teeming with diverse ‘Asian to Caribbean cuisines.’ 7 However, the tide has turned with the wave of gentrification sweeping through recent years, displacing a significant part of this community. This shift is attributed to the growing interest among the younger demographic in arts and culture, ultimately reshaping the landscape into one dominated by “high-priced vintage and art stores advertising to a very contrasting audience,” 8 akin to the offerings within Spitalfields Market today.

Harvey’s discourse on heritage, elucidated in his publication – ‘Heritage Pasts and Heritage Presents: temporality, meaning and the scope of heritage studies’, sheds light on a critical aspect – the understanding of the term itself. He asserts that we ought to “understand heritage as a process, or a verb, related to human action and agency, and as an instrument of cultural power in whatever period of time one chooses to examine.” 9 This emphasises the profound influence of community members in shaping the intangible heritage attributes of an area. They hold the authority to articulate the narrative of history, providing heritage with its intrinsic value and underlining the imperative to uphold these legacies across generations.

2 Maimunah Ramlee, Dasimah Omar, Rozyah Mohd Yunus, and Zalina Samadi, ‘Revitalization of Urban Public Spaces: An Overview’, Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences (2015) 360, 360, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877042815048351

5 Salerton Arts Review’ (London Arts, Theatre and Heritage Reviews and Recommendations), ‘Layers of History in Spitalfields’ (2021), (online) https://saltertonartsreview.com/2021/04/layers-ofhistory-in-spitalfields/ (website) (accessed 18 December 2023)

6 Hafsa Khizar, ‘Brick Lane: A case study for gentrification gone wrong’, 4 August 2022, https://www.voicemag.uk/blog/11456/brick-lane-a-case-study-for-gentrification-gone-wrong (web blog (accessed 19 December 2023)

During the 1980s, Brick Lane underwent a ‘property-led regeneration’ 10 plan prioritising economic over social aspects for the local community. However, this plan transitioned to a ‘culture-led approach’ 11 initiated by the City Challenge, “the UK’s first major urban regeneration initiative of the 1990s.” 12 This shift continued with the Single Regeneration Budget (SRB), emphasising social development, and culminated in Cityside Regeneration, ‘an agency’ 13 formed to deliver an £11.4 million program named “Building Business” (SRB3) in Tower Hamlets. The program aimed to break stereotypes, support local businesses, boost tourism, and promote local intervention in decision-making.

The journal article named ‘Perceptions of Small Business Owners of Culture-led Regeneration: A Case Study of Brick Lane in Spitalfields,’ by Sylwia Tokarska presents challenges and criticisms sourced from interviews with Asian-British business owners associated with Brick Lane for over five years. These interviews unveiled struggles faced by small business owners coping with operational costs. They also highlighted concerns about the potential threat to the area’s Bengali culture and the uncertainty surrounding Banglatown’s future.

The plan initially aimed to elevate small businesses and the local economy, with a particular focus on the restaurant sector to attract tourists and foster economic growth. However, this narrowed the diverse Bengali culture to just an array of homogenous ‘curry houses,’ 14 sidelining varied local shops representing diverse ethnic backgrounds, who add to the cultural elements in the community. As a result, this transition resulted in a reduction in diversity, affecting the broader spectrum of the Bengali community’s cultural identity. It also impacted various businesses representing diverse cultural backgrounds, underscoring a prioritization of economic aspects over cultural richness. Thus, ‘marginalising and creating challenges’ 15 and failing to address rising ‘rents and rates’ 16 which have caused many businesses to struggle.

needs for the sake of economic convenience. It “seems to be used as a catalyst to further property and economic-led development of the area, which is associated with the gentrification process.” 23 Once money-making becomes the driving factor, the “area becomes fashionable and vibrant,” 24 thus attracting affluent residents which then ‘stimulate gentrification.’ 25 Spitalfields Market arguably contributed significantly to the neighbourhood shift and circumstances in Brick Lane. This is evident in the dense increase in commercialisation seen today, thereby fostering the process of gentrification. Goods becoming expensive, property around the area becoming unaffordable, and new communities settling in all contribute to social segregation.

Consequently, the question posed is: where does this leave architects, designers, and urban planners? Their expertise in design, spatial planning, and understanding of the built environment enables them to play a crucial role in shaping the outcomes of regeneration initiatives. They must be cautious of new development projects that prioritize interests and outcomes solely for economic welfare.

This essay acknowledges that the people of Brick Lane according to the journal article are not particularly pleased with the outcomes of the regeneration, reflecting on the uncertain future of their area. However, this essay aims to conduct its own survey to further examine and justify the economic impact on the cultural value of Spitalfields Market and its neighbouring areas. Therefore, in response to these examinations, this dissertation aims to consider whether the development of Spitalfields Market as a modernised and commercialised hub can be deemed successful for the social sustainability of its local community or if it diminishes cultural heritage values, thereby neglecting the needs of the people. It also aims to highlight that architects have a social role in architecture and should work to mitigate issues of social segregation.

Consequently, the area turns into a ‘tourist bubble’ 17 where the human experience becomes “predictable – a visitor comes and has a curry meal” 18 and then leaves as there is no distinct ‘ethnic culture’ 19 to engage visitors for extended periods. It rightfully becomes “a commercial lane with curry houses next to one another,” 20 thus becoming a moneymaking street, which has prioritized commercial interests over preserving the unique cultural identity and heritage of the area. Evans seems to sympathise with this perspective, mentioning that “each story of regeneration begins with poetry and ends with real estate.” 21

The ‘culture-led approach’ 22 seemingly transforms into an economic-driven strategy, disregarding local voices and

In conclusion, this chapter takes a firm stance on how economic interests influence regeneration projects in Spitalfields Market and its adjacent area, Brick Lane. It underscores the importance of creating socially sustainable urban spaces that prioritise community needs, thereby providing social benefits for all. This can be achieved by embracing human-centric design, ensuring community voices are heard, and incorporating the expertise of architects and designers. Preserving the cultural heritage of communities, especially like the Bengalis in Brick Lane, should be a focal point in decisionmaking for regeneration projects. Architects, designers, and urban planners need to prioritise cultural significance alongside economic gains. Projects solely driven by economic objectives risk eroding heritage while boosting local economies. Striking a balance between both culturally led approaches and economic considerations is essential in urban projects to ensure equitable benefits for all.

SPITALFIELDS MARKET HISTORICAL EVOLUTION

This chapter aims to provide a comprehensive exploration of Spitalfields Market, elucidating its intrinsic nature and functionality. Additionally, it will offer a contextual backdrop detailing the market’s historical evolution over time, explicating its transformative journey and shedding light on its present-day significance and identity. Through these means, I will address the key intention of the dissertation, which is to question how the economic interests of Spitalfields Market have changed its cultural value.

Spitalfields Market, located in the historic East End of London, has evolved into a renowned and vibrant commercial hub, offering not only diverse dining experiences for families and friends but also serving as a marketplace for an array of goods such as textiles, antiques, art, and fashion items.

The market boasts a rich history dating back to the 13th century when the area was originally rural, characterised by pastures and gardens ‘until the Great Fire of London’ 26 altered its landscape. By 1666, during the reign of King Charles II, traders began selling at the current market site to respond to the surging demand for fresh produce, such as; fruits and vegetables. 27 Its success played a pivotal role in attracting settlers and migrants from diverse ethnic and cultural backgrounds. For instance, Huguenots fleeing persecution in France brought their silk-weaving skills, Irish weavers migrated due to the decline in the Irish linen industry, and in later years, Eastern European Jews escaped massacres and tough living conditions in Russia. 28 Additionally, the Bangladeshi community sought a better life in London with low-cost housing and diverse job opportunities, thriving in Spitalfields and “bringing new cultures, trades and business to the area including the famous Brick Lane restaurant district.” 29

In 1876, Robert Horner, “a former market porter” 30 , secured a short lease on the market and embarked on constructing a new building for £80,000, completed in 1893. 31 The market, now situated in the ‘Horner Buildings’ continued to flourish until “the City of London acquired direct control of the market” 32 by 1920. As the market’s reputation grew in popularity, It posed challenges such as traffic congestion in the narrow streets, hindering much-needed expansion. Consequently, in May 1991, the market was forced to relocate to Leyton, receiving the name ‘New Spitalfields Market,’ specialising in the trade of fruits and vegetables. 33 The original site retained its significance as Spitalfields Market, undergoing a redesign of market stalls by Foster and Partners in 2017 and earning the designation ‘Old Spitalfields Market.’ 34 This historical journey of Spitalfields Market reflects its cultural significance as it is “the home to many different communities” 35 and an area with a strong sense of community.

26 ‘Spitalfields’,

In the context of investigating how the economic interests of Spitalfields Market have influenced its cultural value, the 19th century witnessed a transformative expansion. During this period, the market not only traded food, drinks, and fresh produce but also material items, such as “vinyl fairs, clothes, arts, crafts, and jewellery.” 36 This shift was emblematic of the changing economic landscape driven by influences of the ‘Industrial Revolution’ 37 in which “East London was at the heart of it all,” 38 where “new machines, industries, technologies and ideas…revolutionised production, trade, transport and society.” 39 Alongside this were cultural and social transformations, the influx of skilled migrant communities, such as the “Huguenots…[who]…settled mainly in Spitalfields and became skilled silk weavers,” 40 and rapid urbanization. These factors collectively led to shifts in consumer preferences, extending beyond basic foodstuffs. Consequently, this diversification broadened the market’s economic and cultural horizons, attracting artisans, traders and consumers seeking cultural artefacts.

Moving into the 20th century Spitalfields Market encountered both challenges and opportunities. The impact of the two World Wars further altered its economic landscape and ‘landscape of the city’ 41 to accommodate the evolving needs of the community. 42 Today, the market stands as a vibrant amalgamation of its historical legacy and array of goods influenced by the economic interests of vendors (see Figure 4.0, 4,1 & 4.2). The market has adapted to both technological advancement and the rise of ‘globalisation’ 43 to meet consumer demands. As Begum puts it, “The term ‘globalisation’ is useful to explain the local-global dynamics in Spitalfields.” 44 The market has not only become a local treasure to the area but also a destination for international visitors, reflecting the interconnectedness of economic and cultural values in the 21st century.

In providing the historical evolution of the market and its economic and cultural transitioning the research objective is emphasised and questions; to what extent does the economic interest of Spitalfields Market take over its cultural value for the better of communities? This is a question I will investigate and analyse further in the dissertation.

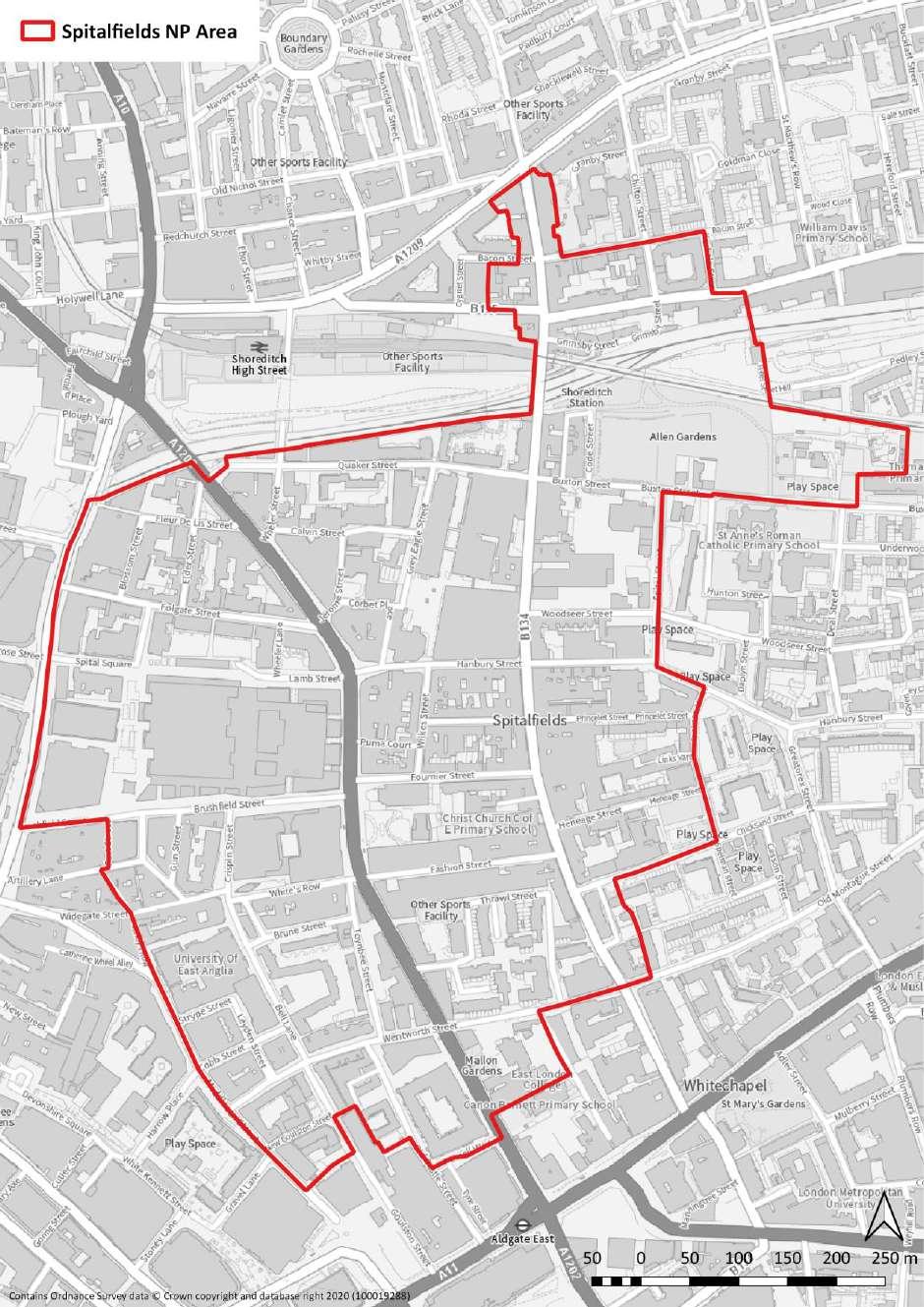

According to the Spitalfields Neighbourhood Planning Forum document which seeks to improve the socio-economic and environmental aspects of the existing neighbourhood areas and proposes a vision for 2035, (see Figure 3.0) Spitalfields “character is threatened by what many perceive to be over-development by businesses, both small and large, seeking to cash in on the neighbourhood’s popularity.” 45 The proliferation of retail stores and businesses in the vicinity has eroded the cohesion of the local community and compromised the historical and cultural essence that has long defined

economically, has detrimental consequences for residents and established customers. As articulated in ‘Past In The Present,’ about the concept of gentrification in Spitalfields, one “would be extremely disappointed if today you were to head to Spitalfields in search of an affordable home.” 46

Gentrification is a central concern in urban public spaces, particularly evident in Spitalfields, with profound implications for the market. The circumstances attract a wealthier demographic, contributing to the neighbourhood’s improvement 47 but also resulting in a transition from a low to a high-value area, marked by escalating property values and the displacement of long-standing residents. However, this is an issue the council is hopeful to address for the future with an increase “of at least 58,965 net additional homes by 2031, with at least 50% of these being affordable.” 48

In conclusion, this chapter has provided an in-depth historical account and evolution of Spitalfields Market providing its importance economically and culturally as a prominent public space used by its local communities and visitors. The transformation of the market characterized by the growth in retail stores and businesses has brought both opportunities and challenges for locals. While the economic revitalization of the area has added to its vibrancy, it has concurrently led to the erosion of the cultural significance that once defined it. The impact and consequences of gentrification underscore the complex interplay between economic development and the preservation of community identity. Thus, it becomes imperative to balance both factors ensuring that future development endeavours prioritize inclusivity, community engagement, and sustained well-being of all residents.

Spitalfields Neighbourhood Plan Submission (Regulation 16) Version

33 Flaven Building Solutions, ‘Old Spitalfields Market,’ (online) https://flaven.co.uk/projects/teashop2/ (website), (accessed 20 December 2023) 34 id

35 ‘Spitalfields Neighbourhood Planning Forum’, Spitalfields Neighbourhood Plan 2020-2035, Submission (Regulation 16) Version October 2020, (online), https://www.towerhamlets.gov.uk/ Documents/Planning-and-building-control/Neighbourhood-Planning-Documents-March-2021/3-Spitalfields-Neighbourhood-Plan-Compressed.pdf (accessed 11 November 2023), pg 8

36 Historic London Tours, ‘Fruitation: Spitalfields Market’, (online) https://historiclondontours.com/tales-of-london/f/fruitation (website) 26th October 2022, (accessed 20 December 2023)

37 Alison, East London History, ‘The role of East London in the Industrial Revolution’, (online) https://www.eastlondonhistory.co.uk/the-role-of-east-london-in-the-industrial-revolution/ (website) 23rd March 2023, (accessed 20 December 2023)

Imperial War Museums, ‘London In The Second World War’, (online) https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/london-in-the-second-world-war#:~:text=The%20Blitz%20on%20London%20from,were%20 killed%20by%20enemy%20action (website) (accessed 20 December 2023)

id

Halima Begum, ‘Commodifying

Figure 4.0

Figure 4.1

Figure 4.2

THE CONCEPT OF COMMUNITY

This chapter aims to explore and deconstruct the multifaceted concept of ‘community’ within urban contexts, focusing on the dynamic and evolving nature of communities like in Spitalfields Market and the impact today on its neighbouring areas, such as Brick Lane, which has brought a shift to the demographic landscape. It begins by examining the foundational definitions proposed by scholar Gerard Delanty and transitions into an exploration of Spitalfields Market and its neighbourhood as the main case study, illustrating the complexities inherent in understanding and sustaining communities within an urban setting.

The concept of community, as discussed by many scholars, poses a challenge to arrive at a fixed definition as it can have ‘many forms.’ 49 A community is ‘socially constructed’ 50 by the people involved and is subject to change, evolving due to internal pressures from social dynamics and economic shifts, and external pressures from urban regeneration, gentrification, and globalisation trends which have been alluded to earlier in this dissertation within the context of Spitalfields Market the neighbourhood shift.

Defining the concept of community proves challenging within academic discourse, given its diverse interpretations that vary among individuals and across scholarly perspectives. Delanty articulates that a community ‘exists in many forms,’ 51 stating, “There is not one kind of community that is more ‘real’ than other forms, or that all kinds of community are derivative of a basic community.” 52 He elucidates on various community types: “traditional face-to-face…virtual… transnational…[and] one-world…which often complement each other.” 53 The notion of a ‘traditional face-to-face community’ 54 can be simplified into a ‘local community,’ 55 of an area, important within the context of this dissertation. He accentuates the specificity of the dissertation discourse further when he points out that “Local community…is…a central question in all discussions…[and]…whether the urban form of the city accommodates it.” 56 Delanty highlights the significance of the ‘local community’ 57 within the broader concept of community, suggesting its reference to social connections, interactions, and shared identity among residents within a specific geographical area or neighbourhood. And that is what holds substantial importance.

this perspective underscores the significance of urban planning and design, not solely addressing the physical needs of inhabitants but also supporting the social fabric and sense of community within specific neighbourhoods. Failure to address social issues arising from regeneration projects risks wasteful investment and detrimental social consequences.

Consequently, in this context, the concept of community aligns closely with Delanty’s definition “that community must be understood as an expression of a highly fluid communitas – a mode of belonging that is symbolic…[and]…capable of sustaining modern and radical social relationships as well as traditional ones.” 58

He emphasises the critical interrelation between the physical layout, planning, and functionality of urban spaces, especially arising from urban regeneration projects and their role in nurturing cohesive local communities. A conducive urban design promoting social interaction and a sense of belonging among residents, rather than purely serving economic interests, fosters the preservation of vibrant and interconnected local communities. Hence,

49 Gerard Delanty, ‘Community’, Taylor and Francis Group, 2003, pg 166

In the context of Spitalfields Market and its influence on the surrounding area, the adverse effects are evident within the regeneration projects. These initiatives have diminished the sense of community and eroded the area’s heritage. Moreover, their influence has contributed to the contemporary rise of globalization and gentrification, resulting in negative effects on the area.

The impact of globalisation is characterised as “the intensification of worldwide social relations which link distant localities in such a way that local happenings are shaped by events occurring many miles away and vice versa.” 59

This concept revolves around a location initially serving as a local commercial centre, gradually expanding to become a global hub influencing various locales across different countries in their purchasing of goods. This is evident with Spitalfields Market, which previously occupied land covered in pastures, evolved into a hub for selling fresh produce, and has now transformed into a prominent ‘local-global’ 60 market, described as “a hip place to buy everything from art to organic foods to ethnic jewellery,” 61 operating every day of the week.

However, as Begum aptly notes, it has brought “implications for all spheres of social identity and life – the economic, the political...as well as the cultural.” 62 This interconnectedness between local and global ‘dynamics’ 63 undeniably shapes communities and cultures, as evident in Brick Lane today. Globalisation does not solely impact broad global systems but significantly influences local contexts. The economic growth spurred by Spitalfields Market has incentivised governments overseeing regeneration projects to prioritise commercial interests over the area’s heritage value.

Another significant impact, particularly on communities like the Bangladeshi in Brick Lane, is gentrification. Having also been at the centre of discussions, there is more concern with “describing the process than with explaining it.” 64 Coined by

German-British sociologist and urban planner Ruth Glass, it can be “defined as the rehabilitation of working-class innercity neighbourhoods for upper-middle class consumption.” 65 Brick Lane itself stands as a testament to gentrification’s phases as it is “itself a gentrification tale.” 66 The influence of Spitalfields Market’s commercialisation has extended to Brick Lane, transforming it into primarily a commercial centre featuring numerous restaurants and few shops offering material goods. This surge of upscale establishments has reshaped the Bengali demographic and undermined their cultural heritage while attracting wealthier communities.

Globalisation arguably contributes to this phenomenon by promoting tourism when areas undergo vibrant, attractive regeneration primarily for economic gain. Consequently, these regions become tourist-centric zones, altering their authentic character, and displacing local community practices. As Brouillette successfully notes, “tourists...visit the area in increasing numbers, and more and more non-Bangladeshis...are attracted to the idea that it [Brick Lane] might be possible to move there.” 67

This increased visibility due to rising tourist numbers drives up property values and social displacement, a hallmark of gentrification. In Brick Lane’s housing, soaring property values render real estate less affordable for long-term residents and small businesses. Consequently, original inhabitants and local enterprises struggle with escalating rent costs. As a minority of these residents relocate and the affluent settle in, community bonds fracture, leading to heightened social segregation and a loss of social cohesion.

To conclude, this chapter aimed to present the concept of community within the context of modern architecture and urban planning, delving into its complexities. It further highlights the impact of globalisation and gentrification in the vicinity of Spitalfields Market and its neighbourhood. The chapter underscores the crucial significance of acknowledging local communities as custodians of an area’s heritage in the design of urban public spaces. Architects, designers, and urban planners hold significant influence. Their objective should centre on crafting spaces that nurture community, encourage social interaction, and cultivate a sense of belonging, steering away from transforming these spaces into mere tourist-centric zones. Spitalfields Market and Brick Lane serve as pivotal examples where parts of their heritage have been sacrificed for upscale retail outlets and restaurants. Thus, the emphasis should not lie in creating transient spaces where “one comes, makes one’s way, gains prosperity, and then leaves for greener pastures.”

Mural by Mohammed Ali Aerosol

UNVEILING PERSPECTIVES

This chapter delves into the economic influences shaping both Spitalfields Market and its neighbouring community, Brick Lane. It presents diverse firsthand perspectives and opinions of residents, traders, and visitors on the regeneration of the areas. The aim is to uncover the multifaceted impact of economic forces on the cultural fabric of these historic locales. Through candid interviews and dialogues, the objective not only elucidates the complex and intertwining relationship between the economics and the cultural essence of the areas but also honours the authenticity of the community’s perspectives, which are formed by the bustling life in these districts.

The following section introduces seven anonymous respondents who form an integral part of the Spitalfields local community and the neighbouring Brick Lane area. The aim was to gather their insights and opinions regarding the area’s regeneration and the consequences of gentrification. The questions below were posed to some participants, including market traders, residents, regular visitors, and business professionals in Spitalfields Market and Brick Lane:

1. Have you experienced any impacts of gentrification on the affordability of living and working spaces in Brick Lane and Spitalfields Market?

2. How has the influx of tourists affected the local community and businesses in this area?

3. Do you believe the changes brought about by gentrification have enhanced or diminished the sense of community in Spitalfields Market and Brick Lane?

4. In your experience, how have the demographic shifts influenced social interactions and community cohesion in Spitalfields Market and Brick Lane?

“I sell vintage clothes and moved here recently to be close to the market, to cut down on long commutes. When checked out the house prices and rent, I was quite shocked. But, you know, I had no other option and was prepared to pay.”

“One good thing about all the changes happening here is more tourists coming in. It really livens up the market and the local scene. It is cool to see people enjoying different cultures. I cannot deny it, it does help us, traders!”

Participant 3 (Brick Lane resident) responding to question 3:

“You know, living in Brick Lane now is like having a front-row seat to a cultural melting pot. Today it is a vibrant mix of traditions, colours, and flavours that make every day an adventure. But I have seen so many changes - fancy shops popping up, and some close neighbours leaving because of rent issues. So, you could say the sense of community has diminished somewhat, as the area is not like it used to be. However, it is still home.”

Participant 4 (Brick Lane resident of Bengali heritage) responding to questions 3 and 4:

“You know, these changes, they have torn the fabric of our community here in Brick Lane. Gentrification is like a flood washing away what made this place ours. It almost feels like it is not about improving, but rather about erasing our sense of community. With these shifts, the connections and bonds that were once shared just are not the same. We used to know each other, share stories, and feel like family. Now, it is like we are strangers in our neighbourhood.”

Participant 1 (market trader) responding to question 1:

“In all honesty, it hasn’t been easy at all. have been a local here for nearly 30 years, living just a few minutes’ walk away from the market. I believe I speak on behalf of almost every trader like me. The rental costs are a significant burden and are what barely keep my business afloat. While the regeneration efforts might appear aimed at aiding us, traders, and business operators, we do not entirely obtain the benefits. So, yes, that’s my personal take on the impact of gentrification on our working spaces.”

Participant 2 (market trader) responding to questions 1 and 2:

Participant 5 (Brick Lane business operator of Oat Coffee Brick Lane) responding to questions 1 and 2:

“Yep, gentrification made living and working around the area including Brick Lane very pricy. Rents have shot up making it tough for us business owners.”

“In terms of tourists, see many around the area and at our coffee shop. With more visitors, the focus has shifted away from the Bengali culture that used to be a significant part of this area. More visitors mean increased demand, leading to higher prices, which, if you ask me, is a positive to an extent. However, on the flip side, smaller businesses like ours

struggle to cope with the high operating costs and these changes.”

Participant 6 (Brick Lane business operator of Bangladeshi restaurant Amar Gaon) responding to question 2:

“Although many international visitors and non-locals come to dine in the area from time to time, it is tough to witness the neglect of Brick Lane’s Bengali culture. What this area embodied years ago is not reflective of its present state.”

Participant 7 (local market visitor) responding to questions 3 and 4:

“Changes due to gentrification have had an impact on the vibe around Spitalfields Market. There is this new sheen with numerous high-end shops, but what’s lacking is the sense of community, that strong feeling of togetherness that used to define the area. It has taken a hit. There is less familiarity among faces, a perceived decline in the sense of connection, and an increase in social exclusion. This is my perspective; others may have different experiences and perceptions.”

To conclude this chapter, through the examination of the viewpoints expressed by various individuals connected to Spitalfields Market and Brick Lane, a multifaceted narrative emerges, reflecting the complex impact of gentrification and the dynamic community shifts in these areas.

closeness and shared history that has been affected by the changing landscape. Their sentiments underscore the significance of gentrification, causing a sense of displacement and estrangement within the neighbourhood they once called home.

Additionally, local visitors have noted a clear shift in the community atmosphere, noting a decline in familiarity among faces and a perceived weakening of social connections. This transformation has stirred a sense of disconnection and exclusion, indicating a departure from the cohesive community fabric these spaces once embodied.

The amalgamation of these responses provides us with a nuanced picture of the repercussions of gentrification and demographic shifts. While economic changes and increased tourism have brought both benefits and challenges, the sense of community, belonging and cultural heritage appears to have undergone a significant transformation, leaving footprints among those who once thrived in these close-knit neighbourhoods. These responses emphasise the need for a more holistic approach that balances economic development with the preservation of cultural heritage and the nurturing of community ties.

Market traders voiced their struggles due to rising costs, highlighting how regeneration efforts intended to support them might not fully address their difficulties. Their experiences shed light on the financial strains faced by long-standing locals, revealing the limitations of regeneration initiatives.

Regeneration as understood provides vibrancy to the area for communities but stimulates the influx of tourists which presents a double-edged sword for small businesses. While it increases business prospects to a degree, it comes at the cost of overshadowing and, in some cases, diluting the authentic cultural identity that once defined these neighbourhoods.

Residents, particularly those of Bengali heritage highlighted the erosion of community bonds, reminiscing about the

Conclusion

To conclude this dissertation, the exploration of Spitalfields Market’s evolution and its impact on the surrounding neighbourhood, the interconnectedness between economic interests and cultural heritage emerges as a pivotal theme.

The historical journey of Spitalfields Market, from its origins as a local market for fresh produce to its current status as a bustling commercial hub, reflects the transformative power of economic growth. However, this growth has not been without consequences. Urban regeneration initiatives, while driving economic prosperity, have led to the erosion of cultural identity and social displacement, particularly evident in Brick Lane.

The concept of community, as discussed in this dissertation, underscores the dynamic and multifaceted nature of urban spaces. The changing landscape of Spitalfields and its neighbourhood, influenced by globalisation and gentrification, has reshaped the fabric of these communities. This evolution has highlighted the delicate balance between economic development and the preservation of cultural heritage. Architects, urban planners, and designers hold a significant responsibility in shaping these spaces and so must use their voices effectively. Their role is to create socially sustainable environments that prioritize community needs and cultural preservation.

The study of Spitalfields Market and Brick Lane serves as a poignant reminder of the importance of acknowledging and safeguarding cultural heritage within the realm of urban development. While economic growth is essential, it must not come at the expense of cultural richness and community cohesion. This dissertation emphasises the need for a balanced approach that integrates economic progress with heritage preservation. Future urban regeneration projects should prioritise inclusivity, community engagement and the sustained well-being of residents. Steinfeld and Maisel clarify the concept of universal design adopted by architects and states that “universal design supports people in being more selfreliant and socially engaged” 69 and it “makes life easier, healthier and friendlier.” 70 For local communities to thrive with redevelopment, the people must have a say and participate in the design. It is imperative to create spaces that foster a sense of belonging, encourage social interaction, and preserve the unique identities defining these neighbourhoods. Architects and designers must address the challenges of social segregation for community sustainability. Only through the harmonious integration of economic interests and cultural heritage can we truly achieve socially sustainable urban spaces that benefit all members of the community. However, sometimes community needs cannot be entirely met, reflecting the extent to which architects themselves know what can be achieved.

Bibliography

69 Edward Steinfeld and Jordana Maisel. Universal Design: Creating Inclusive Environments, John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2012, pg 28

BOOKS

Delanty, Gerard, ‘Community’, Taylor and Francis Group, 2003

Giddens, Anthony, ‘The consequences of modernity’, Polity Press, 1990

Palen, J. John and Bruce London, ‘Gentrification, Displacement, and Neighborhood Revitalization’, State University of New York Press, 1984

WEBSITES

Alison, East London History, ‘The role of East London in the Industrial Revolution’, (online) https://www.eastlondonhistory.co.uk/the-role-of-east-london-in-the-industrialrevolution/ (website) 23rd March 2023, (accessed 20 December 2023)

Flaven Building Solutions, ‘Old Spitalfields Market,’ (online) https://flaven.co.uk/ projects/teashop2/ (website), (accessed 20 December 2023)

Historic London Tours, ‘Fruitation: Spitalfields Market’, (online) https:// historiclondontours.com/tales-of-london/f/fruitation (website) 26th October 2022, (accessed 20 December 2023)

Imperial War Museums, ‘London In The Second World War’, (online) https://www. iwm.org.uk/history/london-in-the-second-world-war#:~:text=The%20Blitz%20on%20 London%20from,were%20killed%20by%20enemy%20action (website) (accessed 20 December 2023)

JOURNAL

ARTICLES

Brouillette, Sarah. “LITERATURE AND GENTRIFICATION ON BRICK LANE.” Criticism, vol. 51, no. 3, (2009), 425, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23131523 (accessed 22 Dec 2023)

Evans, Graeme, ‘Measure for Measure: Evaluating the Evidence of Culture’s Contribution to Regeneration,’ Urban Studies, Vol. 42, (2005), 1, http://www.scholarson-bilbao.info/fichas/16EvansUS2005.pdf (accessed 22 Dec 2023)

Harvey, David, Heritage Pasts and Heritage Presents: temporality, meaning and the scope of heritage studies, International journal of heritage studies, vol. 7, no. 4 (2001), 319, https://www-tandfonline-com.uow.idm.oclc.org/doi/ pdf/10.1080/13581650120105534?needAccess=true (accessed 22 Dec 2023)

Sibley, David, Geographies of exclusion, London: Routledge 1995

Steinfeld, Edward, and Jordana Maisel. Universal Design: Creating Inclusive Environments, John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2012

Woolley, Helen, Urban Open Spaces, London: CRC Press LLC, 2003

Khizar, Hafsa, ‘Brick Lane: A case study for gentrification gone wrong’, 4 August 2022, https://www.voicemag.uk/blog/11456/brick-lane-a-case-study-for-gentrification-gonewrong (web blog) (accessed 19 December 2023)

‘Past In The Present’ (Travelling The World, Discovering The Past). ‘In Spitalfields: When gentrifiers were to be applauded for saving neighbourhoods’ – 10th May 2018. (online), https://pastinthepresent.net/2018/05/10/in-spitalfields-when-gentrifiers-wereto-be-applauded-for-saving-neighbourhoods/ (website) (accessed 12 November 2023)

Salerton Arts Review’ (London Arts, Theatre and Heritage Reviews and Recommendations), ‘Layers of History in Spitalfields’ (2021), (online) https:// saltertonartsreview.com/2021/04/layers-of-history-in-spitalfields/ (website) (accessed 18 December 2023)

‘Spitalfields’, History, (online) https://www.spitalfields.co.uk/spitalfields-history/ (website), (accessed 11 November 2023)

Pantelidis, Ioannis, W. Geerts, S. Acheampong ‘Green generals, jade warriors: the many shades of green in hotel management,’ London Journal of Tourism, Sport and Creative Industries, 3(4), (2010), 8, file:///C:/Users/User/OneDrive/Documents/ Year%203/CC3/Green_Generals_Jade_Warriors_The_Many_Sh.pdf (accessed 22 Dec 2023)

Ramlee, Maimunah, Dasimah Omar, Rozyah Mohd Yunus, and Zalina Samadi, ‘Revitalization of Urban Public Spaces: An Overview’, Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences (2015), 360, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/ S1877042815048351 [accessed 10 December 2023]

THESIS REPORT

Begum, Halima, ‘Commodifying Multicultures: Urban Regeneration and the Politics of Space in Spitalfields’, Doctoral Thesis, Queen Mary College, University of London, 2004

‘Spitalfields Neighbourhood Planning Forum’, Spitalfields Neighbourhood Plan 2020-2035, Submission (Regulation 16) Version October 2020, (online), https://www. towerhamlets.gov.uk/Documents/Planning-and-building-control/NeighbourhoodPlanning-Documents-March-2021/3-Spitalfields-Neighbourhood-Plan-Compressed.pdf (accessed 11 November 2023)

ILLUSTRATIONS

Figure 3.0: https://www.towerhamlets.gov.uk/Documents/Planning-and-buildingcontrol/Neighbourhood-Planning-Documents-March-2021/3-SpitalfieldsNeighbourhood-Plan-Compressed.pdf

Figure 5.0 5.2: https://www.lonelyplanet.com/articles/brick-lane-london-walking-tour