OZZY FOREVER.

CELEBRATE

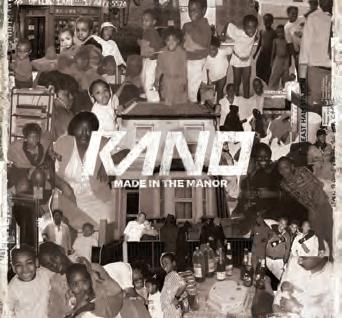

BLACK HISTORY MONTH

CHAMPIONING BLACK VOICES ALL YEAR ROUND

WE HONOUR THE LEGACY WE CREATE THE CHANGE WE MOVE THE CULTURE

Contributors

Adrian Sykes is a widely-respected UK music industry veteran who, amongst many other things, founded Decisive Management – which steered Emeli Sandé to the peak of her success. In this issue he speaks to Ammo Talwar, a key figure in the Birmingham music scene and the Chair of UK Music’s Diversity taskforce.

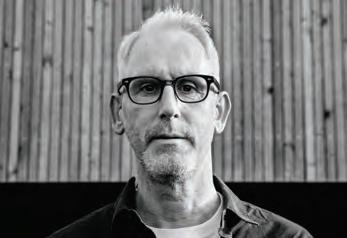

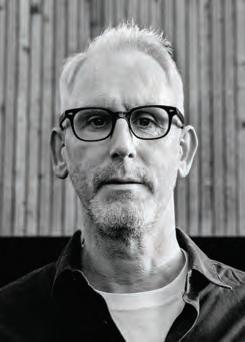

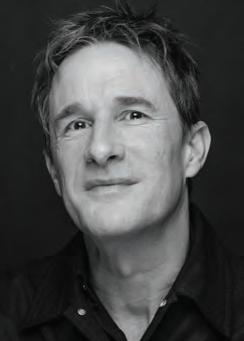

Mark Sutherland has been covering the music business for over 25 years. He is a Variety columnist and writes for publications including Rolling Stone and Kerrang!. He was previously Editor of UK trade title Music Week. In this issue, he talks to Sleep Token manager Ryan Richards as well as Martin Goldschmidt and Rob Collins at Cooking Vinyl.

Alex Robbins is a renowned British illustrator whose work has previously appeared on the likes of the New Yorker, Time Out, Wired, TIME and i-D. Oh, and Music Business UK. He has once again created our cover image. For this issue of MBUK he visualises some wise words from the subject of our lead interview, Peter Edge.

Murray Stassen is the Editor of Music Business Worldwide and a regular contributor to Music Business UK. Stassen, has previously written for the likes of VICE, The Line Of Best Fit, Music Week, and Long Live Vinyl. In this issue, Stassen takes a deep dive into five numbers behind the biggest stories and trends of the past quarter.

MBUK columnist Eamonn Forde has been writing about the music business since 2001. He contributes to The Guardian, Music Business Worldwide, IQ and The Quietus among other titles. His new book, 1999: The Year The Record Industry Lost Control, is out now. This month he muses on the possibility of mediation preventing band break-ups.

MBUK’s newest columnist Sammy Andrews is a leading figure in the global music industry, renowned for her expertise and vision across digital strategy, marketing and technology. In her latest column she takes a fresh look at AI, suggesting that whilst it is of course sending seismic tremors through the industry it is also exposing some pretty severe fault lines that already existed.

FOUNDER’S LETTER

There’s a thread running through this issue of Music Business UK that cuts straight to the heart of what makes music still matter in 2025. It’s about the stubborn refusal to chase the obvious – and how that contrarian instinct is quietly reshaping the industry.

Take Sleep Token. Streaming consultants might tell you that metal bands need to pick a lane: be heavy or be melodic, not both. That the algorithm doesn’t do sonic mongrels. Yet manager Ryan Richards describes a band that deliberately defies categorization: “There’s as much pop, R&B, electronic and piano-led music as there is heavy guitar” in their sound. The result? A Billboard 200 No.1 and the biggest US streaming week for a hard rock band ever. “It’s not a metal band: it’s just an artist painting with many colours,” Richards explains.

Peter Edge at RCA has built his entire philosophy around this principle. While others chase algo-pleasing obviousness, Edge leans into that element of surprise. “I’ve always been attracted to things that seem unlikely,” he says. “Music is changing, and I think this current generation is much more open to combinations [of genre] that people might once have thought wouldn’t work.”

RCA’s roster proves his point – from Sleep Token’s genre-fluid mystique to SZA’s uncategorizable artistry. “We’re not in the business of making widgets,” Edge adds. “We’re in the business of working with people who change the way other people feel.”

The pattern repeats across different corners of the industry. Sarah Boorman at Universal Music UK doesn’t spend her days pursuing the industry’s teenage obsession. Instead, she’s focused on under-13s – a demographic traditionally abandoned to Disney.

Her insight is beautifully simple: “It’s easy to spark a lifelong passion – if you create the spark

Tim Ingham

“Some of the most successful individuals in the music biz are ignoring what algorithms would suggest.”

in the first place.” While much of the industry optimizes for viral moments, Boorman is building actual infrastructure for the first flushes of musical discovery.

Jon McClure can always be relied upon to embody a contrarian spirit. When conventional wisdom says nightclubs are dying, McClure’s Day Fever moves the party to daytime. When industry logic suggests premium pricing, he charges £11. When everyone else chases the youth market, he targets people in their thirties and forties.

McClure’s philosophy cuts to the heart of how creativity thrives precisely where conventional business logic fails: “In that void where commerce and industry have fallen, culture is like the weeds that grow around the margins.”

What’s striking amongst these different perspectives is how often the contrarian bet pays off precisely because it’s contrarian.

Sleep Token’s mystique works because anonymity is rare in our oversharing age. RCA’s artist-first philosophy succeeds because most labels treat musicians like data points. Day Fever thrives because it offers what nobody else is providing. Boorman’s youth strategy works because the industry is too often happy to let would-be young music fans drift into the arms of the gaming industry or – that fourth circle of parental hell – social media.

We might be living in the age of algorithmic optimization, but some of the most successful music industry figures are systematically ignoring what algorithms would suggest.

They’re betting on timeless human truths: that mystery creates meaning, that authenticity resonates more than perfection, and that sometimes the smartest business move is refusing to treat art like a product.

The algorithms can optimize themselves. Creating the unexpected is back in vogue.

Contact: Enquiries@musicbizworldwide.com

Advertise: Rebecca@musicbizworldwide.com

In association with

‘WE’RE IN THE BUSINESS OF WORKING WITH PEOPLE WHO CHANGE THE WAY OTHER PEOPLE FEEL.’

In November, Peter Edge will receive the Sir George Martin Award at MBW’s Music Business UK Awards in London. We sit down with the British-born, Los Angeles-based RCA boss to discuss artistry, major record companies, and the value of human creation...

RCA Records operates on a philosophy that prioritizes artistic vision – and consistently proves that patience pays off.

Peter Edge, the label’s Los Angeles-based CEO, has spent the better part of two decades building what he describes as a “premium content” philosophy.

Edge’s achievements will be formally recognized in November, when he receives the Sir George Martin Award at Music Business Worldwide’s Music Business UK Awards in London.

It’s an honor that, appropriately, celebrates executives who combine commercial success with unwavering support for artistic vision.

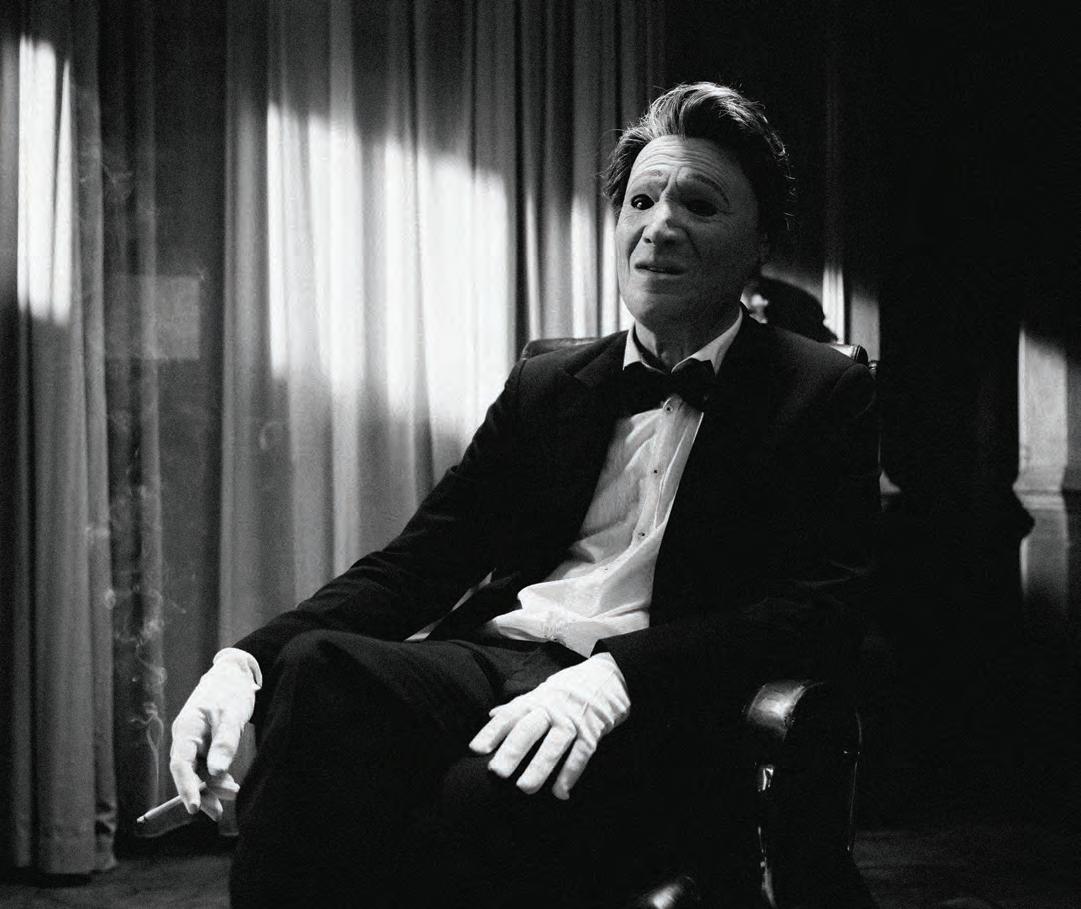

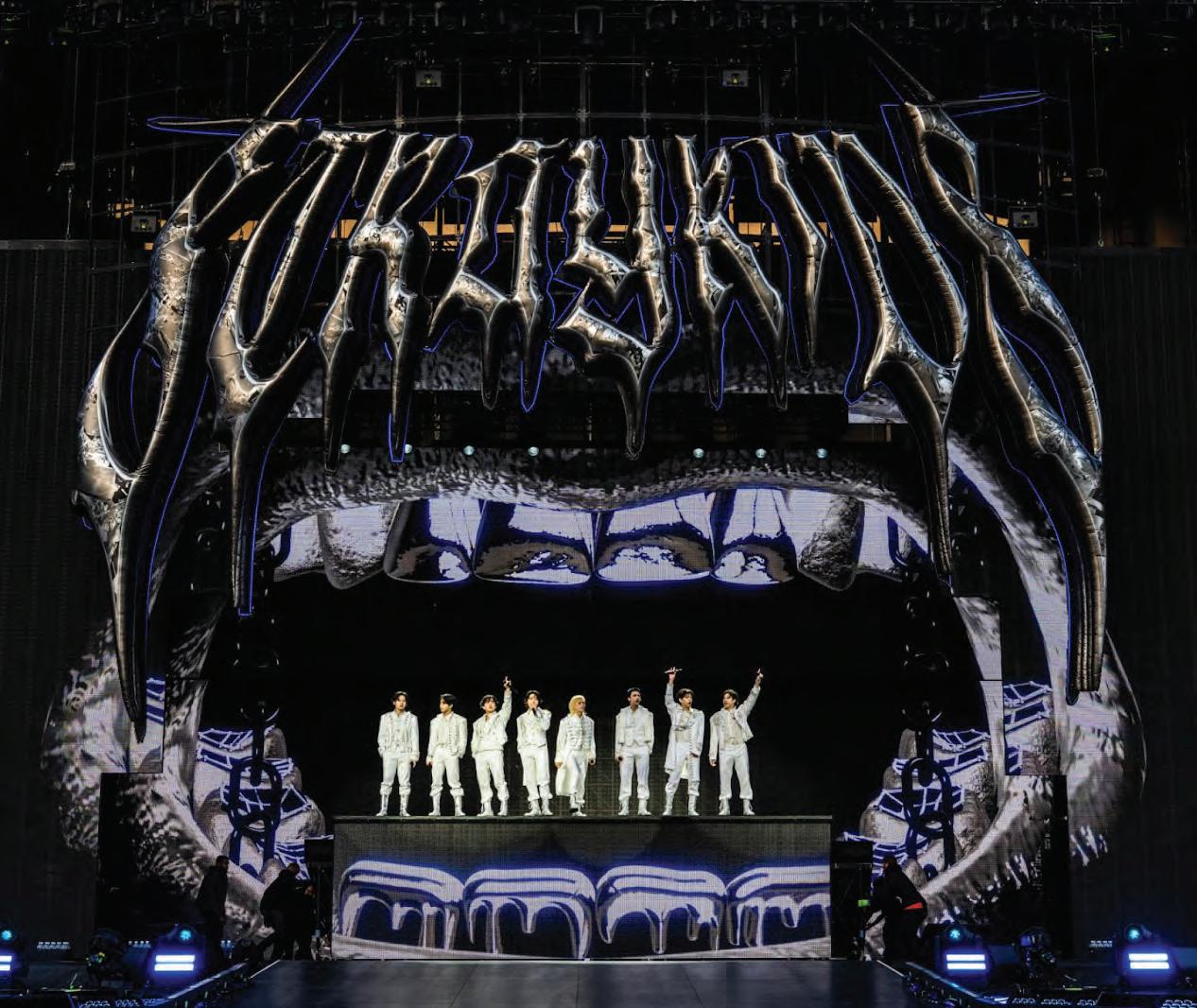

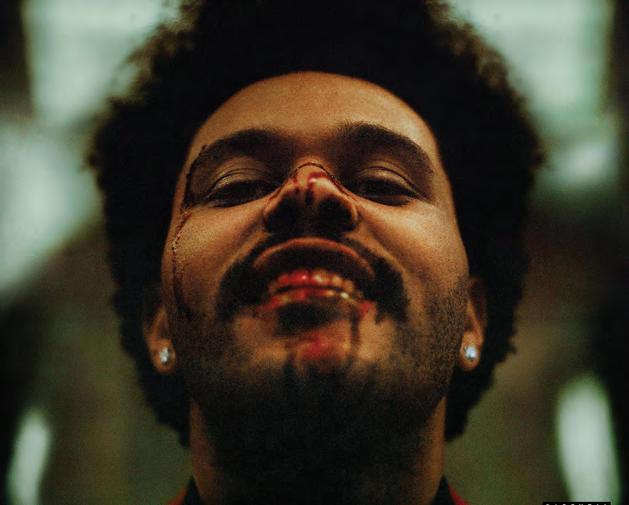

2025 has been a year that perfectly encapsulates Edge’s approach. Sleep Token, the mysterious British metal outsiders, mesmerized audiences both in the US and around the world, with stunning results – including their latest album topping the Billboard 200 in May.

Elsewhere, Tate McRae’s pop evolution reached new heights; her latest album, So Close to What, also became a Billboard 200 No.1 in February.

during the pandemic years, when the industry pivoted toward viral content and instant gratification.

The label maintained its long-term vision, focused on building lasting careers rather than chasing fleeting moments. That strategy continues to pay dividends: the label now boasts some of the most culturally significant artists of the streaming age, each defying easy categorization.

“We’re not in the business of making widgets,” Edge notes, referencing a commodified A&R approach he’s spent his career rejecting. “We’re in the business of working with people who change the way other people feel.”

Tellingly, as AI encroaches into the music business more and more, Edge remains confident in art with a soul. He notes: “Perhaps the thing that is going to be most valuable in music is the human part – the part that isn’t copyable… the part that isn’t based on some kind of predisposed formula.”

“We’re not interested in telling artists to compromise. We don’t believe ‘it’s all been done before’.”

Meanwhile, Tyler Childers continued his genre-defying artistry, LISA’s solo venture stretched K-Pop convention, Doja Cat roared back with the ‘80s-inspired Vie, and the likes of Myles Smith and Wolf Alice demonstrated a slick collaboration between Edge’s US-based label and Sony Music’s UK operation.

Then, of course, there’s SZA. The past 12 months have seen a triumphant LANA deluxe re-issue for her huge SOS album, while she also found time to top the Billboard Hot 100 with Kendrick Lamar on Luther

At the same time, SOS has continued to cement its place as a global modern staple; according to Sony Corp data, it was Sony Music’s biggest global record for the firm’s past two fiscal years.

“I’ve always been attracted to things that seem unlikely,” Edge explains from RCA’s offices, reflecting on the label’s eclectic roster. “Music is changing, and I think this current generation is much more open to combinations [of genre] that people might once have thought wouldn’t work.”

RCA’s ‘gradual road to greatness’ philosophy was naturally tested

Below, MBUK speaks with Edge about building careers in an age of shortened attention spans, why “premium” artists are winning in a crowded marketplace, and how RCA became the anti-algorithm major label…

When Music Business Worldwide last interviewed you in 2019, you likened your approach to HBO: “Premium content for a subscription audience.” How has that philosophy evolved in the streaming age?

Creatively, RCA has the same mindset as a large independent. Artists’ constant ability to play with genre and reinvent themselves really excites us; we’re not interested in telling them to compromise, and we don’t believe ‘it’s all been done before’.

Even if something strongly takes a cue from another era, you can marry it with a contemporary point of view.

We combine that artistic appreciation with an understanding and expertise around data and reaching global audiences.

On the data and marketing side, what’s changed from a few years ago?

Things are way more complex than they ever used to be.

It’s a very subtle process to influence what people are open to

connecting to. There’s no ‘one thing’ you can do to open that door.

We focus on audience perceptions and influences, putting things in the space around people and allowing them to gestate to become meaningful cultural moments.

Look at what the RCA team put together with Sleep Token –this incredible long-lead campaign ran for six months, bringing the fan into a world completely created for this album. It’s mysterious, intriguing, and compelling. It meant you were glued to what’s going on.

It shows what you can do with long-term planning and trying out things that are not necessarily the tried-and-tested ‘this is how you release a record’.

Sleep Token is a key example of genre fluidity on RCA from the past year. How did that signing happen?

We’d been observing them building an incredible fanbase from the records they’d released previously. Kudos to Dan Chertoff and Daniel Schulz on our A&R team for realizing and spotting what was going on with them very early.

It was a curious one, as started listening to their music deeper I kept hearing real references from other genres, in particular R&B. I realized this artist was drawing from references that are hardly ever drawn on in music broadly defined in that way [as hard rock/metal].

It speaks to what I was saying earlier: this current generation is much more open to hearing combinations of things that people might have previously thought would be unlikely to work.

I notice you keep talking about the artists… I’m going to have to trick you into talking about yourself at some point. The artists are why we’re here. I’ve never wanted to be known for anything other than supporting artists, partnering with artists, and helping them achieve their goals.

It’s hard for them to be out front, to put themselves out there and take the risk that people may or may not appreciate what they’re trying to do. Playing a supporting role to them is a great privilege.

During the pandemic, the industry pivoted toward viral hits. How did RCA maintain its long-term philosophy?

In 2020, amongst everything else going on – socially, politically, this extraordinarily strange time that nobody could ever imagine – it all felt a bit like, ‘What is this music about?’

Most of the time [listening to new popular music at the time], it didn’t feel like people were going to look back on that period and go, ‘Oh my, these songs are forever songs.’ To use the current parlance, they were ‘moments’. We actually benefited from some of that: Doja Cat had some huge ‘moments’ in 2020 and 2021, but we knew she was never just a ‘moment’ – we’ve worked with her for a long time.

“I’ve never wanted to be known for anything other than supporting artists.”

I’ve always been attracted to that idea. The idea that something so different and eclectic [as Sleep Token] could work on RCA, to me, was never in question.

Tyler Childers also fits into this conversation: he’s a country artist, but also far from ‘just’ a country artist.

Tyler is completely his own thing. He’s become this generation’s North Star for artistry in so many ways.

He’s a remarkable guy because his views about life, his interests, and influences, are completely unpredictable.

Now I think about it… SZA is R&B, but she’s also not R&B. This is becoming a theme.

SZA is… as SZA does! She’s whatever she feels and wants to do, and there’s no box you can put her in. She’s very sure about that.

Credit to our partners at TDE, Top and Punch, for seeing that years ago and just believing in her artistry.

Her music is raw and emotional yet beautifully melodic, like some of the great artists of the past decades.

SZA is just so real. If I wasn’t working with her, she’d still be one of my favorite artists.

She’s an artist who’s entirely unpredictable and fascinating, and has a long career ahead of her, as you’re seeing now as she enters her Vie era.

That raises a broader question about artist development. There’s a narrative that majors just don’t do it anymore.

I would argue that RCA kind of disproves that. Tate McRae is a great example. We signed her when she was 15 or 16, building from the platforms she’d created on YouTube as a dancer and songwriter.

We’ve built her career together from a very small beginning into somebody who’s become one of the breakout artists of this year. Her album and everything associated with it are remarkable.

What do you look for when signing artists?

What is unique about this artist? What do they do that nobody else is quite doing the way they do it? What are they about that’s not duplicated elsewhere?

I think of Steve Lacy. This is a guy who defined his own destiny – whether making amazing songs in his bedroom at 16 or 17 or now, forging something so specific.

People like that are very exciting to me because their vision and their ability to make something really singular and unique, creatively their own thing, is remarkable.

It’s interesting that you focus a lot on the people you’re signing, their character, not just their music. It leads to a philosophical

conversation about human authenticity versus artificial intelligence.

With everything going on with AI and music, perhaps the thing that’s going to be most valuable is the human part – the part that isn’t copyable… the part that isn’t based on some kind of predisposed formula. How heartfelt, how authentic, how unusual is this piece of expression? That’s always been one of the most interesting things about music.

I was speaking to a young DJ recently and he said his peers have a very sharp eye for authenticity: ‘That person is not being real, that’s a commercial ploy, this content is not actually authentic.’

The antennae for what’s real amongst Gen Z has been tested over and over by the digital age, and maybe they’ve had enough. That could have a big impact on artistry.

It used to be the case that the industry had ‘majors’ and ‘indies’, with a strict dividing line. That’s changed a lot, especially thanks to the deals that get done, with more artists owning rights and licensing to the majors. But culturally, too, there’s no great issue with ‘signing to a major’ from the indie ecosystem. I’ve just seen you’ve signed two artists from the ‘indie’ world – Alex G and Blood Orange.

“Artists are not widgets. It’s fun to work with people who don’t compromise what they want to say.”

Throughout my career, what’s frustrated me has been seeing the ‘we make them like this’ approach – changing [an artist’s sound] so they fit a preconceived notion of what audiences will like.

Artists are not widgets. I love it when great artists in the ‘margins’ of [culture] get popular. It’s fun to work with people who get to grow their audience without compromising what they want to say.

Artists can come here and our philosophy is like, ‘No, we don’t want to alter your vision – we want to make your vision bigger.’

I love that. It’s the antithesis of ‘we make them like this’ thing.

I suppose Blood Orange and Alex G are both prominent artists in what we might have once called ‘alternative’ or ‘indie’ music. But everything’s broken down now; those labels are disappearing.

You’ve been at Sony/RCA for over two decades, following your successes at J Records working with Clive Davis. Why does Sony’s structure support your artistic vision?

To develop artists and see them through, you have to stay in one place for a long period of time. That comes with the territory.

I’ve been fortunate that [Sony Music Group Chairman] Rob Stringer shares that vision of artist development – he’s been involved with many artists’ careers over a long period of time.

Rob’s also a music guy. Not only does he believe in artist development, but he’s also a big fan of music.

And then I look to the people around me. To name just one, John Fleckenstein is such a major part of RCA – he’s in the center of everything. He’s creative, but he’s also extremely solution-oriented and practical. He has a really good way of translating philosophical thoughts into practical application. That’s invaluable.

Over the past few years, the industry has seen the rise of catalog music dominating consumption on streaming services. How do you view that challenge?

From a business perspective, obviously frontline labels face challenges when everyone listens to music from other decades. But on a creative level, it’s actually a really good thing.

I love the idea of a ‘collapsed timeline’. I grew up through the ‘90s listening to music from all over, which is a very British thing to do. There was a whole culture of absorbing music from different times and places. Now [because of streaming], we’re seeing younger artists are influenced by a much broader range of music.

I think about some new projects we have at RCA that are imminent. Look at The Red Clay Strays, who just go from strength to strength in terms of being a band that blends country,

Americana, and rock. They’re a very unique prospect, playing larger and larger venues, with a new album on the way next year. Their time is coming.

Tems has been such an important voice coming out of the new Afrobeat scene in Nigeria, but frankly she’s gone beyond any genre and any borders. She has that very special and unique voice and writing skill. I’m very excited to see her fulfill all of her potential.

Other artists we’re excited about include Victoria Monét who won Best New Artist at the Grammys last year [2024] –there’s lots of anticipation around her next record. And I’ve just been listening to kwn from the UK, who’s creating a whole new take on what ‘R&B’ could be, from a different viewpoint we’ve seen before.

Do you ever worry that the transitory nature of media consumption amongst young audiences – short-form video, plus all that choice of catalog music – is going to kill fandom of new artists?

No. The thing that’s so potent with younger artists is that they’re here now, playing live to crowds of people directly like them.

With all the [screen time] we experience in our lives, headphones in, people are really craving experiences in real life. And for us as a label, the live arena is really great as an artist development tool - it tells you much more than listening to a recording or even an inperson meeting can. n

‘I DON’T SEE ANY CEILING – THE SKY’S THE LIMIT’

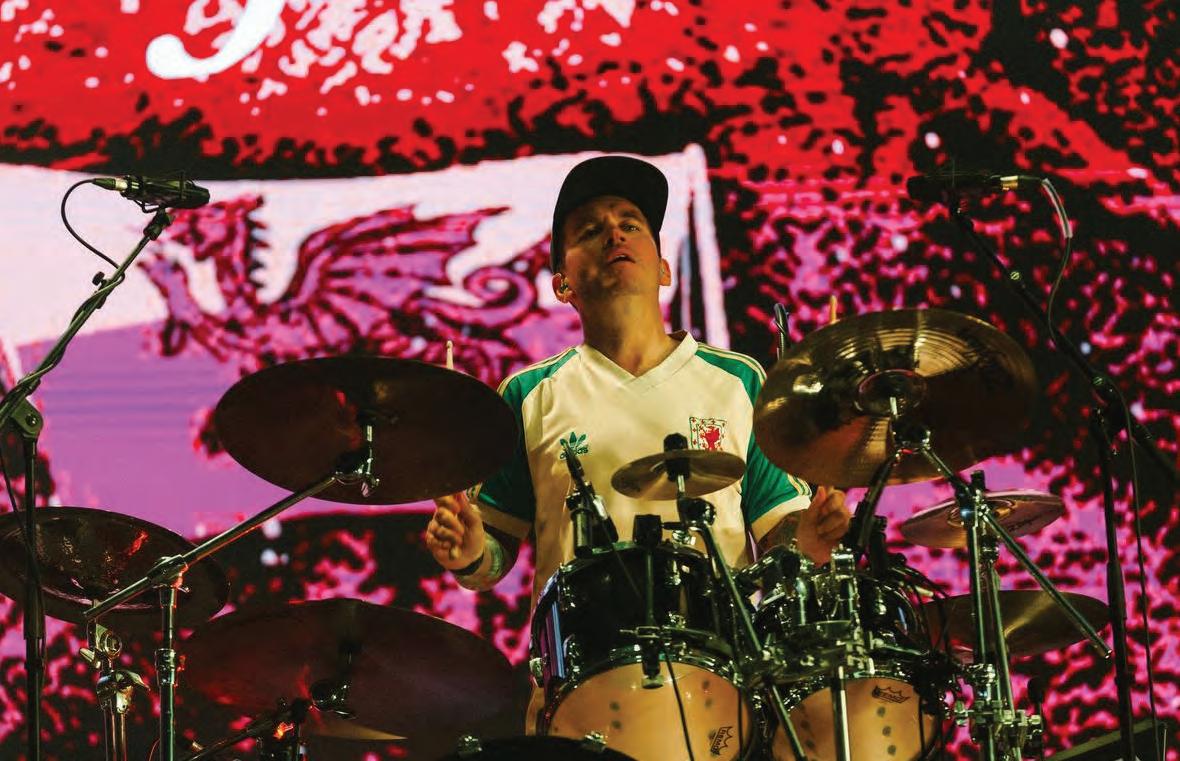

Ryan Richards enjoyed some pretty serious success as the drummer in Funeral For A Friend. But as the manager of Sleep Token, he’s heading to a whole new level…

Ryan Richards looked like he was on top of the world. He was the drummer/scream vocalist in Welsh post-hardcore legends Funeral For A Friend, one of the most successful UK rock bands of their generation, touring the world and playing to thousands of adoring fans.

After five albums and hundreds of gigs, however, in 2011 Richards found himself getting his thrills elsewhere. No, not in the sex-and-drugs-and-rock’n’roll lifestyle that has distracted so many drummers over the years, but in the little wins achieved by the local bands back in his native South Wales that he was advising and helping out.

It was that, combined with a desire to spend more time with his young family back in the Valleys, that saw him sit down for a chat with the band’s manager, Craig Jennings of Raw Power Management.

“I said, ‘I think my touring days are numbered’,” Richards recalls. “‘This management thing is where my passion is and where I see my future going forward’.

“A few days later, Craig rang me up and said, ‘If you’ve made up your mind to do that, why not come and work with us at Raw Power and learn there?’ It was a massive learning experience, and so helpful to my development as a manager. It was the perfect next step.”

Nor is it likely to be a one-off. Richards has cultivated a roster of fast-rising rock acts, including the likes of Those Damn Crows, Holding Absence, Bambie Thug, President, Zetra and Dead Pony.

They’re the sort of bands Richards would have loved in his own South Wales youth, when he was encouraged in his musical abilities by his family, at first playing piano/keyboards before settling on the drums when his musical tastes – initially shaped by a babysitter who would play him Bon Jovi and Guns N’Roses –became too heavy for tickling the ivories to be involved.

He played in a number of local bands before joining Funeral For A Friend. He realised the band was going places when they scored a Kerrang! feature that tagged them, ‘The most exciting new band on the planet’.

“Then it was like, ‘Right, I guess we’d better get serious’,” he chuckles. The band signed to Atlantic Records UK and Sanctuary Artist Management (after Rod Smallwood saw them play at the Kerrang! Weekender in Camber Sands) and Richards settled into the unofficial role of liaison between band and industry advisors on their unstoppable rise to rock stardom, marking him out as a future exec in the making.

“Not to self-aggrandise, but I always thought that this is where it would end up.”

Fourteen years on, Richards has his own management company, Future History, and is himself one of the most successful rock managers on the planet. In a UK industry starved of breakthroughs, the huge success of Sleep Token – one of three bands he had on his roster when he left Raw Power to set up Future History in 2018 – has been remarkable.

The mysterious, masked UK rockers have headlined Download Festival, signed to RCA in America and scored a No.1 record with their fourth album, Even In Arcadia, on both sides of the Atlantic. More to the point, their pop sensibilities, hyper-engaged fanbase and savvy use of online marketing have taken them to places other rock and metal bands can no longer reach: Hot 100 hits, latenight TV appearances and the biggest US streaming week for a hard rock band ever. That’s ever.

This is uncharted territory for a rock band in 2025, but Richards is taking it all in his stride.

“Not to self-aggrandise, but I always thought from the start that this is where it would end up,” he chuckles. “I was always a true believer.”

When Sanctuary dissolved, Funeral stayed under Craig Jennings’ wing at Raw Power (“I still consider Craig a mentor,” he says), while Richards started helping out local bands by passing on contacts and helping them secure gigs.

He joined Raw Power when he went full-time with such management concerns, working his way up before leaving when he found himself again spending too much time away from Bridgend (“Wales keeps drawing me back: the green, green grass of home that Tom Jones sang about really is that magnetic,” he laughs).

Initially, he worked alone from his home office, meaning he and his artists could weather the Covid shutdown due to his low overheads, but Future History is now expanding rapidly, with Download Festival boss Andy Copping joining as a director.

Accordingly, Richards – who spent the summer back in the reformed Funeral For A Friend, playing the band’s biggest ever gigs, including a headline at Cardiff Castle – fizzes with plans for the likes of Bambie Thug (who just signed a publishing deal with Universal), President (“Out of any band I’ve ever worked with, that’s been the quickest out of the traps,” he declares) and the reviving rock genre in general.

“It’s hard work being a rock band,” he says in his mellifluous Welsh tones. “Climbing up that hill can be a slippery and steep

slope. But, with rock being such a growing genre, I’d like to think it might empower the scene to have more leverage or influence. We’ll certainly keep trying…”

Before that, however, he sits down with MBUK in his Bridgend home office on a classically rainy South Wales morning to talk streaming, mystique and why Sleep Token aren’t actually a metal band…

Unusually for a band in 2025, Sleep Token have mystique. How big a part has that played in their rise?

I love that stuff. I was listening to a music industry podcast recently and the topic of conversation was social media and how it’s changed the dynamic between band and fans, and how it’s a shame you can’t do things in the way you used to, when you had that mystique.

Because the band is operating the way it does, in terms of the anonymity and not connecting in the conventional ways with social media, interviews and press, it’s about putting everything around that and giving more substance to the whole story.

You go to a Sleep Token show and, even though the band doesn’t speak in words, there is that unspoken connection and dialogue between the band and the fanbase which is really special, quite unique and very powerful.

“There is an unspoken connection between band and fanbase which is really special.”

And I was thinking to myself, ‘Well, surely you can if you choose to?’ And that’s what it’s been. It’s about wanting to find that magic again, that deeper connection between fan and artist, which conversely comes from that separation, it engenders that deeper connection.

Will you be able to keep all that up, or will there be a ‘Kiss without the make-up’ moment?

The difference there is, it doesn’t feel like anyone – certainly not the fanbase – wants that. They’re not trying to peek behind the curtain, dissect it and invade upon what the band is doing, or to break that fourth wall.

It’s not just about respecting it, but really indulging in it, buying into it and enjoying it for what it is. It was different back in the day with Kiss, and maybe even Slipknot, where it was like, ‘Oh, I wonder what they look like and who they are?’ Now, maybe because the dawn of the internet means information is always at your fingertips, people value having that mystique and separation.

With any movie or TV show that comes out, before you watch it, you can go online and find out the ending. You can spoil it for yourself – but why would you do that? I don’t see anything positive or helpful in that and it seems like people feel the same.

Conventional industry wisdom suggests rock music doesn’t work on streaming. How have you bucked that trend? One of the big things is the understanding of where rock is now. A lot of the listening public have had a skewed vision or perception of what rock/metal/hard rock is and sounds like, informed by music from the past or what they define in their heads as rock or metal.

If you’re a person that never listens to metal, but you’ve heard Metallica, Iron Maiden, Judas Priest or any of the big, heritage metal acts and you don’t like any of those bands, and you’re seeing

a band like Sleep Token described as metal, you’re probably not going to go and check it out.

It’s like, ‘I don’t like Iron Maiden, I probably won’t like Sleep Token’ – which is to completely miss the point. When Sleep Token get put into the metal genre, it’s because that’s the most extreme touchpoint of what the band does.

But there’s as much pop, R&B, electronic and piano-led music as there is heavy guitar; there’s perhaps even more of those other things.

But now the band has had more mainstream exposure and people have heard it by accident or been recommended it, they’re like, ‘That’s not metal’.

There are elements of it throughout the record, but it’s not a metal band: it’s just an artist painting with many colours to portray many different feelings and emotions, and that’s just one of them.

We keep hearing about how few British breakthroughs there are these days. Are Sleep Token getting the industry respect they deserve for their success?

There’s been this wave of optimism and positivity at the place that rock is in, where it’s going and the trajectory it’s on, so it’ll be interesting to see if that’s just in our little circle, or if it permeates into the outer reaches of the industry.

But I’ve been in this industry long enough to know it’s always been this really vibrant and exciting part of music culture and always will be. It never goes away, it never dies, that’s why it circles round to every generation – it remains to be seen if that’s what this is.

It’s not something that I really concern myself with, but it’ll be interesting to see when it comes to the next more mainstream awards. But the response from the fanbase is what it’s all about.

When you joined Funeral For A Friend, did you expect them to become so big?

Well, the difference then was, we measured success as ending up on a covermount CD for an independent music magazine. We were like, ‘We’ve done that, we’ve done a demo and we got to play London – we’ve made it!’ There was no grand plan.

So, we were like, ‘Maybe we could get signed to an indie label or have a booking agent and do some shows with bands we like’, and that was it. But it quickly escalated!

Has going through the ups and downs of being in a band helped you as a manager?

Just having someone with the level of experience, knowledge, respect, contacts and everything else that Andy has, as well as being such a good friend to me and my family, just felt really right. He’s been a really important addition to the company with everything he brings to the table, it’s been a big factor in the successes we’ve had.

If you could change one thing about the music industry, right here and now, what would it be?

I’m sure I wouldn’t be the first person hoping for streaming compensation to be a little more attractive! Particularly for artists that are coming through.

It can be a real lifeblood and a real boost for new artists, being able to actually earn a decent income as they start, just to give them that freedom to remain independent as long as they need to, and give them that structure of being able to develop as an artist.

It’s a shame when you come across a really good artist that has signed away recording or publishing rights on a deal that’s just not good for them, but they’ve been left with almost no choice because they weren’t getting paid any other way. They needed that cash injection, so they signed whatever was in front of them, just so they wouldn’t have to pack it in.

“There’s as much pop, R&B, electronic and piano-led music as there is heavy guitar.”

Absolutely. It’s been the biggest contributor to any success I’ve had in management.

It’s important that I make the distinction to the bands I work with. I say to them, ‘If I’m giving you advice on something, or steering you in a particular direction, it’s not because I’m a knowit-all, have this unique perspective, or have all the answers. I’ve learned as much or more from the wrong steps I’ve taken as a band member or as a manager’. You learn so much from your mistakes. They give you the knowledge.

I always say to them, ‘I’ll never ask you to do something that I haven’t done’ – and that’s pretty accurate really.

Andy Copping has joined Future History – what will he bring to the company?

He’s someone I’ve been close with for many years, and he’s always been a big supporter. When I was coming through with Funeral, he always believed in us, he always gave us really good opportunities through Download or other tours.

And, on a personal level, he’s always been a big supporter of mine. When I left Raw Power to start Future History, he was one of the first people on the phone to say, ‘Hey, if you ever need anything, I’m just a phone call away’.

Then they get stuck in those deals, they get a little further down the line, they’ve spent their advance and they’re back to square one without any commodities to sell and they’re screwed. That’s not all the fault of royalties from DSPs, but that would help.

Is there a difference between Ryan Richards the rock star and Ryan Richards the manager?

[Laughs] No! When it comes to Funeral For A Friend, I’m quite happily back in that position where I’m the one arranging bits and pieces, getting stuff ready, liaising with promoters and booking agents – I don’t think there’s much of a distinction there.

If anything, it’s helped with being able to handle the band side of it in the right way. I certainly appreciate it more; it’s a nice treat to get out there, slip those drumming shoes back on, reconnect with the guys in the band and their families. It’s a nice thing to have on tap when the right opportunities come along, it’s nice that it’s still there.

There are no plans for anything else – perhaps there will be, perhaps there won’t but, if there isn’t, that [Cardiff Castle headline show] would a good one to sign off on.

And how big can Sleep Token get?

I don’t see any ceiling. Fundamentally, across any genre at the moment, you’re looking at one of the best songwriters and one of the most interesting and exciting live acts out there.

And, when you have those two things, then the sky’s the limit. n

‘THERE IS LITTLE MORE IMPORTANT TO ME THAN GIVING CHILDREN THE MUSIC THEY DESERVE THAT WILL STAY WITH THEM FOR LIFE’

From raving in Ibiza with Ministry of Sound to heading up Universal Music UK’s youth strategy – via The Powerpuff Girls and Amy Winehouse – Sarah Boorman discusses her life in music and a job that’s also a vocation…

There’s a danger that the idea of a department dedicated to selling music to children could come across as cynical – but not after listening to Sarah Boorman for more than five minutes.

For a start, she is genuinely enthusiastic and evangelical, driven by a desire to get generation-after-generation passionate about music – proselytising an artform rather than pushing a product.

There’s also that word ‘department’. “I always smile when I hear that”, says Boorman. “It’s just me at the moment. But I plug into amazing teams in the UK and around the world. I sit in Rebecca Allen’s Audience, Media & Strategy team, in Kate Wyn Jones’ Audience stream, building partnerships and initiatives with the labels. And I work closely with David Hawkes, Chief Commercial Officer [UMUK].

ambition to be part of the business. “I remember being in primary school and imagining what it would be like to work with the artists I loved. I’d wonder how you even got to do that. It was a childhood dream that I honestly didn’t think could become reality.

“I studied psychology and economics, but my real passion was always music: listening, playing, dancing, singing, going to gigs. All my hobbies involved it. Where

think I slept properly for four years. It was fast-paced and wild, so much fun, but eventually I started to wonder where it was all heading.

“My friends were getting serious about their careers – finishing law school, PhDs – while I was jumping around Ibiza having the best time, but always skint. I couldn’t ignore the feeling that I needed to focus more.”

That feeling led to a career-defining move that took her away from music, only to eventually deliver her back, this time with a very distinct focus.

“I was in at the deep end. It was the ultimate initiation by fire, and I absolutely loved it.”

“I also work within a global UMG Committee focused on younger audiences. A highlight has been partnering with Bree Bowles at Republic Kids in New York. She’s phenomenal, and we’ve built a great relationship.

“I try to keep things fluid with the labels. I add the most value by building wider opportunities and partnerships that artists can tap into. But if a label ever wants me to lean in on a specific campaign, I do. Breaking and developing artists is the most important thing we do as a company, and I’m always there when needed.”

Boorman’s love of music goes back, appropriately enough, to childhood. Perhaps more unusually, so does her

it all came together was music marketing. It makes sense now, but the universe still had to shift in just the right ways for me to get here.

The first sign of movement came when Boorman was President of her University Students’ Union and suddenly had to deliver a Freshers’ Week event with almost no notice. She recalls: “Ministry of Sound came to the rescue. I met the team, we clicked, and before I knew it I had abandoned my Master’s plans and joined Ministry of Sound in a super entry level role.

“I was thrown straight into the deep end – everything from compilation licensing to guestlists. It was the ultimate initiation of fire, and I absolutely loved it. I don’t

“I became Marketing Manager at Cartoon Network, working on what we then called new media strategies for characters like Tom And Jerry and Johnny Bravo. It was fun in a totally different way – sometimes it felt like living inside a cartoon, with creatives bouncing jokes around and chucking jelly beans across the office.

“It was a brilliant time, not least because it was the only point in my life where work actually stopped at 6pm. But I really missed music, and I knew I had to find a way back. That’s where the luck came in.”

It wasn’t all luck, of course. And it’s certainly much more than luck that has seen Boorman carve out a career that now sees her working with artists and teams across the world, finding and talking to the music industry’s audience of the future...

How did you get back into the industry and end up at Universal?

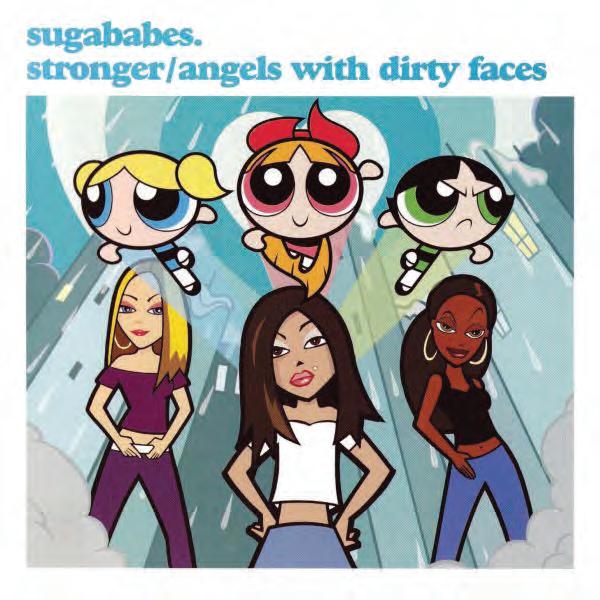

Our biggest property at Cartoon Network, The Powerpuff Girls, were releasing their first feature-length film, and the studio

was looking for marketing ideas that would take them beyond their very young female TV audience.

One day on the tube home, I was reading a review of the Sugababes’ new single Freak Like Me. I loved that band – they’d got me with Overload and Run For Cover – and suddenly thought, The Powerpuff Girls are the Sugababes in cartoon form!

I’m going to age myself here, but one of the first things I ever Googled was, ‘Who manages Sugababes?’ That led me to Mark Hargreaves at Crown Management, who introduced me to Jon Turner at Island, who then put me in front of Jason Iley – then General Manager of the label – at exactly the right time.

Island was going through some changes, and they needed someone new to join the marketing team. We made a cartoon that became the Sugababes’ video for Angels With Dirty Faces, and a month later I was looking after the band at Island. It was fast and incredible. I couldn’t believe how it had all come together.

What was it like working with the Sugababes?

I joined the Sugababes camp in 2002, just before they released their second single on Island (Round Round), and I stayed with them in some capacity until they parted ways with the label in 2010. A lot happened in those eight years!

They made so many great records — Darcus [Beese, then Co-President of Island Records] and the team were on fire with that band. But it was intense, fast, international, and all before digital made travel and promo and even communications easier.

What were the first and most important lessons you learned when you plunged into the deep end of the music industry?

I learned that my role was to be the hub at the centre of a campaign – keeping everything on track, ironing out problems, facilitating communication. Honestly, I often felt out of my depth. I was in my

“To earn respect I had to be on top of everything – but also stay focused and kind.”

For me, the learning curve was steep. I had to get organised – fast. You were juggling production schedules, sales presentations, timelines, budgets, assets, managers and international diaries, all at once. I became studious about my job, but it kept things together in a way that is essential if your band is going to grow fast.

mid-twenties, looking after a superstar act, and I realised quickly that to earn respect I had to be on top of everything – but also stay focused, positive and kind.

Jason and Darcus were my icons at that time. They were totally different in their approaches, but both showed me what

excellence looked like in their respective lanes, so I aimed for somewhere in between, with my style. I remember asking Jason early on, when I was trying to figure out how to prioritise, what really matters to get a hit. He just said, ‘Everything.’ He was right – and that’s always stayed with me.

What were the highlights of your time at Island? And who were your mentors?

Looking back, I can’t believe I was at Island through such a seminal time, and I was lucky to work on campaigns that really got me noticed.

At the beginning, alongside Sugababes, I helped out on Busted, who were having an incredible run. Paul Adam, Louis Bloom, and I worked with Prestige Management to launch McFly, which properly put me on the map in the UK.

I was there from the very start – I still have a Polaroid from the first band meeting. I loved working with them, they were an absolute joy.

Their energy and positivity were infectious and I still talk to them now.

Honestly, it was seeing the reaction of the young fans that really hit me the hardest. Even now, I’ll still meet executives even now who say to me, ‘You helped launch McFly? They were

my first gig, my first album – they were everything to me!’

Breaking Bombay Bicycle Club meant a lot, because until then I’d never broken an ‘NME band’. They were clever, passionate, and inspiring.

Plus there was Jessie J, Tinchy Stryder, The Wanted, Taio Cruz, The Feeling, Mika, Florence + The Machine. It was an amazing time, and I was only running half the label!

But the ultimate highlight has to be Amy [Winehouse]. I knew her from day one at Island, and because I didn’t work on her record at first, we could just chat as friends. I remember SXSW the year she showcased. She was nervous but, when she delivered her acoustic set, you could hear a pin drop. I have goosebumps just thinking about it. Later, when I did end up marketing her record, it was magic. I’ll never forget Darcus walking into the office with Rehab

on a CD, fresh from New York with Mark Ronson, playing it to us and asking what we thought. We were speechless – it was clearly something special.

By the time I left Island, when my second child was born, I was General Manager. Loads of huge international acts were coming through – The Weeknd, Ariana Grande, Drake. It was incredible, but also relentless – endless promo trips and late-night conference calls (pre-Zoom). With two really young kids at home who needed me, I was ready for the next chapter.

gave me advice, had my back, and pushed my thinking forward.

Ruth, in particular, showed me how to navigate as a woman near the top. She

UMOD (Universal Music On Demand) came out of UMTV, Universal’s compilation label.

“I’ll never forget Darcus walking in with Rehab, fresh from New York. We were speechless.”

Who were your specific mentors at that time?

We didn’t use that word back then. We were all just getting on with the job. But looking back, Ruth Parrish [Director of Promotions] and Darcus were key. They

was my trailblazer. I’m proud to say both Ruth and Darcus are still two of my closest friends today.

From Island, you joined the Curation and Special Projects division. What did that entail?

UMTV had been hugely successful for decades, but once physical albums started to decline, the label needed to evolve. The wane of physical was directly linked to the rise of streaming and, for a while, playlist curation really made a difference to a track’s success. So our team focused on playlists, creating several in-house brands.

But we also explored anything involving curation – in new, creative ways. Compilations still worked, but we pushed boundaries: Pete Tong with the Heritage Orchestra (which gave us multiple No.1 albums), the Trevor Nelson collections, and the UK version of Kidz Bop.

How did the Kidz Bop collaboration come about and what made it so successful?

Kidz Bop were huge in the US, and their label, Razor & Tie, wanted to expand internationally with a UK group.

The idea was simple but powerful: kids singing family-friendly versions of chart hits, which usually wouldn’t get through streaming filters for younger listeners. It felt risky because it had been years since anything ‘for kids’ had really worked outside of Disney, but we decided to go for it.

ITV heard about the project and loved it. They knew the power of family-friendly pop from The X Factor and backed the band. TV was still a massive driver at the time, and we had incredible kids with real star quality (one was even called Twinkle –born for it!). The music sounded way better than anyone expected. Add in a stellar TV campaign and strong playlisting, and we had the magic formula. The result was three Top 10 albums in the UK – a huge achievement by any standard.

Is that what led to becoming General Manager, Youth Strategies? And was that a specially created role?

Yes and no. Kidz Bop was part of a bigger thought process. I’d already had success with youth-driven acts like McFly, and I’d seen how young fandom could start well before teenage years.

daughter, then aged seven, constantly asked for Let It Go. I thought, when I was her age, I bought Madonna’s Like A Virgin. Where’s that experience for her?’

Then one day, my four-year-old son asked Alexa to play Apricots by Bicep after hearing it on BBC Radio 1 – he had it on loop, jumping around like a little raver. That was a eureka moment; the landscape had changed again, children could access streaming via YouTube and smart speakers, they just needed people to talk to them. So, the Youth Strategies role was about recognising all these threads and creating a space in the business focused on under-13 audiences again.

Is that how you define ‘youth’ - under-13? It depends on the project, but broadly yes, I mean Gen Alpha – kids under 13. GDPR-K in the UK/EU and COPPA in the US set strict privacy rules for under13s: no first-party data, no media accounts without parental permission.

They begin to reject ‘child-focused’ content and insist on their own choices. That’s when music fandom starts – and it sticks for life.

What have been your biggest achievements in the role so far?

I’m really proud of the work we’ve done with Yoto, the audio platform for kids. It was the first global partnership of its kind, and they’ve been the perfect collaborators.

We’ve released classics like The Beatles, Elton John, Queen, ABBA, Bob Marley, Spice Girls, plus Disney and Moonbug projects. And now, we’re starting to release new music as part of artist campaigns.

Yoto is chart-qualifying in the UK too, which is an important factor. But for me, the bigger win is connecting with a younger audience in an innovative way, giving them the ability to choose their own music.

“Honestly, the biggest achievement is starting this whole conversation.”

I’m also proud of Activate, our partnership with Joe Wicks and Studio AKA (Hey Duggee), which launched this summer. It’s the first of its kind, an animated fitness series for kids, with short online episodes featuring tracks exclusively from Universal Music UK artists. It’s being used in primary schools around the UK from September.

At the same time, The Greatest Showman soundtrack was unstoppable, and I realised it was kids and families driving that success. The same happened with Frozen and Encanto. Clean, family-safe albums had incredible staying power.

My thinking was that we needed to A&R for this space again. But the industry had lost its youth-facing platforms: no Smash Hits, no TOTP, no CD:UK, no Chart Show. The download era meant that you suddenly needed a device, an account, and a debit card. By the time streaming and social media arrived, the media landscape for kids had completely changed.

On top of this, my own kids were growing up. I felt sad that the only music they knew was what I played them. My

This means social media is effectively off-limits, outside of YouTube Kids. A responsible youth strategy has to build elsewhere. Advertising is also stricter –no direct-to-consumer messaging, and restrictions around products like alcohol, sugar and fast-food.

I break it down further: zero to seven years is mostly music ‘for kids’, where parents and carers are the gatekeepers.

Seven to 12 years is ‘for tweens’, when kids start choosing for themselves. They want contemporary artists, but delivered into the water supply of where they are.

This second group is fascinating. Around age seven, the two hemispheres of the brain start working together, allowing more sophisticated choices. It’s also the age when many kids get access to iPads, Alexas, gaming consoles.

Seeing children turn screen time into active time while enjoying our music is incredible.

But honestly, the biggest achievement is starting this whole conversation – getting people across the company to support ways to inspire young listeners to find their musical tastes. After all, they are essential to the future of the industry.

What are the keys to getting kids interested in music? And how is it different from marketing to adults?

The truth is, kids are naturally interested in music. Play a track, and they’ll almost always react. They’re curious, open, and absorb everything.

Last year I worked with primary school children on Bob Marley’s 80th celebrations, tied to our Young Voices partnership (250,000 kids singing his songs on an arena tour!).

They were fascinated – not just by the music, but by Jamaica, reggae, the lyrics. It showed me again how easy it is to spark a lifelong passion – if you create the spark in the first place.

The big difference is appropriateness. I spend a lot of time on clean edits – both audio and video. Video is especially tricky. It’s not just about removing explicit lyrics; visuals have boundaries too. But it’s worth it, because future audiences are visual-first. We have to get this right.

meet Ofcom standards for youth viewing.

We’re working with the BBFC to classify videos: determining which are fine, which need tweaks, and which need alternates.

And what are the headline goals for 2026 and beyond?

The video channels will be much more populated by the end of this year, so 2026 will be marketing and development phase for those. I’m really excited to get to there, as I know from the research and insight work I’ve done how much children want these services.

“It’s easy to spark a lifelong passion – if you create the spark in the first place.”

Can you tell us about any projects you’re working on at the moment?

Right now, a huge focus is developing youth music video channels across connected TV and YouTube.

Believe it or not, there isn’t currently a music platform where kids can watch ageappropriate videos. Most videos are made with Vevo/YouTube in mind and don’t

We’ve soft-launched two CTV channels with VOD365: Ketchup Music (for younger kids and parents) and YAAAS! (for tweens who want contemporary music videos).

We also launched 4Tunes on YouTube – a safe space for tweens to watch music videos, short-form content, and creator collabs.

We continue to work closely with Yoto and have some exciting plans to deepen our partnership.

We are also looking at collaborations in the gaming space. The world of age-appropriate but relevant and exciting music curation for younger audiences still has a long way to go, but I am keeping my eye firmly on that process.

There is little more important to me than giving children the music they deserve that will stay with them for life, and, in doing so, build future music lovers. n

‘IT IS REALLY HARD TO BE A LABEL, I DON’T KNOW HOW WE SURVIVED’

As Cooking Vinyl heads towards its 40th anniversary, Chairman Martin Goldschmidt and Managing Director Rob Collins reflect on the label’s story so far, selling to Exceleration, current successes, the state of the indie sector and much more…

Cooking Vinyl is living up to its name.

The veteran independent label may turn 40 next year but, over the last couple of years, its chart performance has really turned up the heat: guiding Shed Seven to the ultra-rare feat of two No.1 albums in a single calendar year, plus releasing smash hit albums by everyone from The Darkness to Alison Moyet, adding to a legacy stacked with records from the likes of Billy Bragg – with whom the label did what’s generally acknowledged as the world’s first artist services deal, back

in 1993 – plus Michelle Shocked, The Prodigy, Baby Metal, Roger Waters, Sophie Ellis-Bextor, Nina Nesbitt and Passenger.

“It’s only taken us 40 years!” chuckles chairman Martin Goldschmidt, who says revenues are higher than at any point since they sold over one million copies of The Prodigy’s Invaders Must Die in 2009. “We’re getting there – slower than British Rail!”

The company – initially set up as a folk label in 1986 by Goldschmidt and Pete Lawrence – has got another lift from its recent acquisition by Exceleration Music, the independent company making waves

across the biz with its blend of acquisitions, investments and label services.

Exceleration was founded by an Avengers Assemble-style group of leading indie execs: Glen Barros (ex-Concord), Dave Hansen (Epitaph), Charles Caldas (Merlin), Amy Dietz (Ingrooves) and John Burk (Concord). Goldschmidt freely admits he was looking for an exit after a lifetime at the indie coalface, but – unlike some of his peers – he didn’t want to sell to a major or venture capitalists.

Consequently, he says the Exceleration deal ticked every box and, crucially,

ensures an independent future for the company and its staff; while Exceleration’s strong US presence and its in-house Redeye distribution company is likely to give a further boost to CV’s burgeoning release schedule.

“We’ve always had a vision of not trying to rip everyone off,” Goldschmidt says. “We try to look after our staff and artists, we’ve always been a stalwart of the independent sector and it’s great to be able to continue those traditions that have always been part of our ethos.”

The company is led day-to-day by another veteran, Managing Director Rob Collins. Collins got the music bug while hanging out with his schoolmates Eater, who were “the princes amongst the royalty on the early punk scene”. His storied career has taken him from the post room at Island, through Virgin, Some Bizarre, Product Inc and Warnerowned Radar Records, as well as a stint in artist management, before he pitched up at Cooking Vinyl in 1999.

He didn’t expect to stay long, but 26 years later, Collins is relishing the challenge as Goldschmidt prepares to ease back slightly. The founder has moved to Totnes in Devon (“He’s a constant thorn in everyone’s side, so everyone’s really enjoying it without him,” laughs Collins, “And you can print that – he’ll see the funny side!”), although he hasn’t quite managed to follow through on the plan to reduce his days just yet.

“We’re both like, ‘What else are we going to do?’”, laughs Collins. But both men enthuse about plans to use Exceleration’s additional resources to supercharge the business, as they prep forthcoming albums from singer-songwriter Callum Beattie and boyband Blue – and eye-up international signings and getting into the catalogue acquisition business.

Before all that, however, MBUK sits down to chew the fat with the two chefs to discuss their unique recipe for Cooking with gas: Collins in CV’s buzzy Camden HQ, Goldschmidt in rural bliss down in Totnes. Starting with the self-styled more garrulous of the pair, Goldschmidt...

“I can talk shit until the cows come home,” he laughs. “And living in Devon, I actually see them come home…”

MARTIN GOLDSCHMIDT, CHAIRMAN

You’ve had offers for Cooking Vinyl before, what was different about the Exceleration one?

It gives me an exit strategy, which was a big goal, but, more importantly, they’re people I know, respect and like.

Charles Caldas is a very old friend of mine and we worked together for a long time. I know the Concord lot, we worked

“Basically, when Universal have power and leverage, they leverage!”

with them on a couple of things and they were always fantastic.

Exceleration are unique in that they’re totally focused on the independent sector. Yes, they’re buying companies, but they’re also building an infrastructure to strengthen independent labels and provide fantastic back-office support. With Redeye, they’re trying to build the best independent distribution network in the world, and they understand the digital space brilliantly.

The other thing it does is give us a very strong presence in North America, which we’ve tried to do several times and never succeeded with. Now, we can compete with anyone in the North American market – we’ve got a fantastic set-up there, so it really enhances what we can do for our artists.

Of course, there are a few changes in the world of indie labels and distribution right now…

What are you referring to, Universal buying everyone? [Laughs] Yeah, that is really scary. I read [PIAS founder] Kenny Gates’

[MBW op-ed] about how nice the people at Universal are it put a massive smile on my face. There are great people working there, don’t misunderstand what I’m saying. But basically, when Universal have power and leverage, they leverage – what a surprise! And any other company would do the same!

That’s not saying they’re all a bunch of evil people, not at all, they’re doing what any big company with leverage would do. Sony do it, Warners, everyone would try – the whole idea of Merlin is for the independent sector to leverage. But to say they’re really nice people who won’t do that did make me laugh.

So, how do you feel about the proposed Universal Music Group-Downtown deal? You could ask the question, why do Universal want it? Downtown’s many things, but it’s not rights, it’s access to market and market share and I understand that But it also worries me that the independents’ access to market is seriously threatened by losing FUGA. There are some great alternatives, like AudioSalad, who Redeye are using, and a few others, so it’s not doom and gloom. But it is a big shame, because FUGA are a great company and a great way for independents to access the market.

The other thing they’ve bought is Curve, the accounting system developed by two of my ex-employees [Richard Leach and Ray Bush, along with Tom Allen], which is brilliant and so many people in the independent sector are using. That doesn’t help them with market share, so you wonder why they want it, because it could easily be sold off to the independents.

It could be that they’re going to roll FUGA and Curve into Virgin and offer a fantastic proposition to independents, but it just makes it harder for people who aren’t part of majors to compete and access the market.

So, do you think IMPALA is right to try and block the deal? I do.

Some people might point out, you sold Essential to Sony – isn’t that the same thing?

It is, yeah. Well, it’s not exactly the same, because there were so many alternatives to Essential in terms of distributors/ aggregators, although it’s helped create a monster in The Orchard. And that’s not a negative, I’ve got massive time for those guys. But they have become pretty big, and we definitely helped with that, for better or for worse.

But FUGA and Curve are different, especially Curve – there are very few alternatives to Curve, and why do [Universal] want to be doing indie label accounting? It just doesn’t seem synergistic with their core business. I’m sure there’s a plan and we’ll find out if the merger’s approved.

Most of the big UK independent music companies have been around for decades. Where are the new ones? Well, there are some great indie labels coming through Korea!

The market has changed. There are a whole number of factors – the dominance of English language repertoire is less and you’re seeing international repertoire becoming more important and having a bigger market share.

Plus, it is really hard to be a label, I don’t know how we survived. I’ve probably learned how to run a label now, just as we’re sold and I’m not needed anymore!

When you did that first artist services deal with Billy Bragg, did you realise how important the model would become for the industry?

Not at all! When you say we did it, it was really simple – [Bragg’s manager] Pete Jenner said, ‘This is the deal’, and I said, ‘Where do I sign?’

I didn’t even think about it, because I really wanted to work with Billy. It was all Jenner’s idea, I can’t claim any credit except for signing the thing.

But it’s actually a fantastic business model. People think it’s great for the artist, because they just see the headline figure that the artist earns all the money.

But it’s actually not as good as all that for the artist, because they also bear all the cost.

But what it does do is really align your interests with the artist. It takes away a lot of the ‘us and them’ that often happens between artists and record labels.

In the olden days, artists used to come in and go, ‘Spend more money on everything, you’re a record label’. And now the conversation is, ‘We could do this, this and this – or we can pay you some money’.

We always say, ‘These are the options, this is what we’d advise, what do you want to do?’ – and it’s fantastic to be able to give them that control. But they make the decisions – and take the consequences.

Is it difficult to step back after 40 years at Cooking Vinyl?

It depends on your team. If you’ve got a really good team and you trust them, it’s a lot easier – and I’ve got a fantastic team.

The big thing I want to say [to the wider industry] is, you’re really privileged little fuckers working in the music industry –enjoy it! Do try to work together more and have more fun. It’s such a privilege to be able to work with artists and music; enjoy the ride!

ROB COLLINS, MD

How have you managed to make Shed Seven bigger than they were in the nineties?

It was real old school: band, label, promo team – everyone just mucking in and all being on the same page. It was like the old Werner Herzog movie [Fitzcarraldo], pushing the boat over the hill.

The band have done it themselves as well, by being so true to what they do. They’re fantastic communicators. They’re geniuses at doing their own social media – they couldn’t do it for another band, it’s not like they’ve got a template we could

roll out for any other band, but the way they talk to their audience is just perfect.

They’re such an honest, hard-working bunch of guys who are really humble with it all, and so thankful they’ve been given this opportunity to come back and be probably more successful than they were back in the day, certainly in terms of selling tickets.

And the competition’s not there anymore, there’s only a few of those bands standing – and a lot of them struggle to do the numbers Shed Seven do.

You’ve done this with a few artists now – is there a formula for reviving people’s recording career?

There’s a loose template that you can apply to a lot of artists and releases, whether it’s The Darkness, who we almost got a No.1 with last year, or Blue, who we’re releasing a new record with next year.

There aren’t 10 things you need to tick that will work for every artist, because every artist is going to lean in in a different way. But to sell the numbers you need to get those Top 5/Top 3/No.1 records, so much is expected from the artist to lean in now, with signings, in-stores, signed stock, delivering on their socials… That’s the template, but it’s almost like an insurance policy when you do a deal to make sure the band is willing to do that work – or else, where are the sales going to come from?

You sell a lot of physical product, but some people in the biz seem to see that as cheating somehow…

Yeah, it’s not real, it’s rigged [laughs]. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with superfans buying the black vinyl and streaming it; or buying a super-deluxe boxset of the same record and not streaming it; or someone who’s just an avid collector and buys all

five vinyl formats because they want each different cover.

I used to buy various formats of records when they came out – the 7”, the 12”, the 2x7”, it’s not new.

I’m not dissing people who only stream, or saying they’re not real fans, but there is such a commitment when you make that purchase, in the same sense that there’s a commitment when you buy a T-shirt or a ticket. It’s at that level. Streaming is more passive.

There’s a lot of competition in the established artist area. What’s your pitch to get people to go with Cooking Vinyl?

We roll out the history – not just the recent history, but the longterm version. The other thing that persuades people is, they meet the team and feel that there’s a group of people who will be here for the foreseeable future.

It’s really stable and they’re really committed – we try and articulate that to anyone who comes in, be it a manager, artist, lawyer or accountant.

It’s about the passion you put in as well, because that can make or break a record –

certain people can come in, the MD can sit there and do a fantastic talk but, when it gets down to the troops, they don’t know, because they’ve never met them.

We like to bring the troops out and say, ‘These are the guys you’re working with, this is the team – you’ve got total access to everybody’. And hopefully they feel something.

“We haven’t had the respect that other labels get and I’m not sure why.”

Did you really try and sign The Smiths when you were at Virgin?

Yeah, but I was pooh-poohed on that one. The people at Virgin just didn’t see it, they didn’t get the songs.

I remember having a cup of tea and fish and chips with the band and their original manager on Portobello Road. But I think

they had their hearts set on Rough Trade; Morrissey certainly did.

In the past, you’ve often described Cooking Vinyl as an underdog. Is that still the case?

I still think we are, even after 40 years. We haven’t had the respect that other labels get and I’m not sure why.

Maybe it’s because there was a phase where Cooking Vinyl wasn’t signing the most fashionable artists. There was an element of having to sign certain artists to keep going. You can only do what’s put in front of you, but some of the press was a bit mean – we used to be called ‘the label where bands go to die’.

Well, now you’re the label where bands go to come back to life… Exactly, we can re-energise, we’re like a Duracell battery.

So, can Cooking Vinyl last for another 40 years?

If the music business survives another 40 years, I don’t see why not! n

‘IT’S ABOUT BRINGING IN FRESH ENERGY – AND THAT FRESH ENERGY WILL CARRY THE WORK THROUGH’

MBUK’s regular check-in with the Did Ya Know? podcast sees Adrian Sykes talking to Ammo Talwar, a key figure in the Birmingham music scene and the Chair of UK Music’s diversity taskforce…

Agreat many lives and careers have sliding-doors moments – pivot points that can take our protagonist in one of two very different directions.

In fact, it’s a phrase and phenomenon that is so common it’s often avoided as being something of a cliché. With Ammo Talwar, however, and the leap of faith that led him into the music industry, there’s no danger of that; he just has to describe what actually happened.

Looking back to his adolescence in early-nineties Birmingham, he says: “I suppose, fundamentally, it was my brother’s fault. I actually graduated in civil engineering. I used to design highsecurity doors for prisons and hospitals. You’ll always need doors, I thought…

“My brother, meanwhile, was managing an artist called Apache Indian, touring the world with an entourage. I had a choice: keep on making doors, or take a chance on a bit of that excitement. So I started Punch Records, a shop heavily influenced by the culture around me.” A career in doors slid away, a life in music opened up.

The music in Talwar’s childhood home was “very spiritual, quite religious”. So what he listened to with his friends was “a form of rebellion”. It included the early Electro compilations, James Brown, Motown and, at school, mainly reggae.

Talwar is proud of – and inspired by – the city where he grew up and still lives. And by a handful of influential figures from the generation before him that shaped Birmingham’s (and the UK’s) Black music scene.

He says: “There was a kind of uptown/downtown split, like the difference between, say, Brixton and the West End. The uptown clubs were more commercial; the community scene was more creative. Our clubs and venues were in the communities, that’s where the new sounds were developed and celebrated.

“Then came the real heroes – the first DJs, promoters, producers and managers to really bridge those scenes. I’m thinking of guys like Mambo Sharma, Shaun Williams, Erskine Thompson and Lloyd Blake. They helped take the community vibe uptown and helped shape popular Black British music in Brum.

“Risk-takers like these gave the people cultural confidence. They gave me confidence to quit engineering and open a record shop selling only Black music.

“We couldn’t compete on the popular side, so we became specialists straight away.”

His more tangible rebellion, ditching a ‘proper’ job to open a record shop, didn’t, however, hit as hard as he expected. “Initially my parents were fine. For the first year they thought I was selling bhangra! They saw me as staying in the culture, running a business.”

Talwar grew up in Aston, a district he describes as having a similar story and cultural outlook as places like nearby Handsworth, Brixton, St Pauls, Toxteth and Chapeltown. “But Birmingham’s streets felt more mixed to us at the time. We had racism, we had oppression, but I think our generation was divided more on class rather than race or religion.

“The Asian community, the Black community, the white community; diversity just felt natural. Like the way we used to move from, I don’t know, roti to jerk chicken to fish and chips. So I suppose it was natural that we would listen to a mix of musical genres; it felt quite fluid rather than forced.”

“Remember, we were up against HMV, Our Price etc., which meant we couldn’t compete on the popular side. So what we did was become specialists straight away.

“And it was a beautiful period, that kind of new jack swing time, sort of pre-grime, all those interesting labels. At the same time, I became a promoter, putting on shows by the artists who were pioneering back then. It was an exciting time and we were at the heart of it.”

Decades later he is still at the heart of it – more so than ever, with a new record label looking to sign and develop local artists.

But alongside that, as part of UK Music, he has also become a key figure in the UK music industry’s drive for diversity and inclusion.

It is a mission he has tackled with real vigour and purpose – and one that he knows he wouldn’t have understood and appreciated without his own unique background…

Punch Records became a real hub, didn’t it?

It did, and if I had it now it would be called an art centre rather than a shop, because our space was open. We had community stalwarts, musicians, DJs, students – we didn’t say no to anybody!

And the people who came in expanded our business – with

Black music always at the heart of it. But we still made no money!

In 2003 I realised I needed to do other things that supplemented the business, and at the same time Napster kind of killed us

But we were lucky, because in 2004, we pivoted into something else, which was, I suppose, the company that most people know us for in terms of touring and festivals and books and all the other bits, but with the same core values as before: openness, fairness, access.

At what point did you feel that you wanted to be more than just a business, and instead make sure you could give people a voice and a platform?

When we moved ‘uptown’ to Digbeth, we saw that, even as a Global Majority city – we are, I think, 54% non-white British – diverse artists and music still weren’t getting into those white spaces: the museums, the arts venues, the galleries. So I set up Birmingham’s first commissioning black festival, BASS, as our response.

measure and evaluate the data on who was participating and who was excluded.

How did you get involved with the UK Music diversity movement?

Most of it was naturally based on the work I was already doing: wanting to make change, looking at the data. And some of it was people wanting fresh opinions – especially from outside London.

“This time around was very, very different. This time people wanted meaningful change.”

Our drive to do that, to push for equality of opportunity and access, was happening around the same time social media was giving more people a voice. Plus, the technology had arrived to

Keith Harris and Paulette Long had set the tone. This wasn’t the usual PR cycle: someone writes a report, you get a couple of quotes in the trade press and you’re good to go. This time around was very, very different. This time people wanted meaningful change.

UK Music was the only organisation that was really getting into the data around the workforce, and had done the hard work around analysing it and saying we need to do more. There’s no point in developing a report if there’s no real impact behind things that you want to do. So we set a robust plan that cut across a lot of the trade bodies, saying we need to do more; we need to be better and lead.

That became the 10-point plan which addressed language, governance, leadership and achievable targets.

What did it specifically set out to do and how much of that has been achieved?

The 10-point plan was a series of things that the industry could do within a defined timeframe. Simple things like, get rid of the word ‘BAME’; don’t use the word ‘Urban’ – and then some tougher things. Like, maybe you need to change your governance structures and review senior leadership. This was mainly targeted at trade bodies that sit under UK Music and about 90% of that work has been completed.

We’ve had loads of wins. We’ve had staff wins, investment wins, and we’ve had organisational wins around companies

that have started looking at things that they just weren’t seeing before 2020.

Across the broader industry, some elements have been picked up, others less so. We always framed diversity as an input to growth and cultural significance rather than an end in itself. We’ve embedded some powerful green shoots that will come out further down the line.

Do you think there’s been real commitment and real change in the years since there was a lot of talk about DEI in the wake of the murder of George Floyd?

There has been some significant change across the last four years, and some companies have really leaned in. But we’ve always said this is a long-term journey and we have some way to go before we are reflective of the UK communities that we serve. The sector is moving, but we need better pace.

Our communities have changed. London is going to become a Global Majority city soon. Birmingham already is. And what we need is our industry to reflect the people that we serve. It’s that simple.

Another area that you’re working hard on is pay gaps, particularly in regard to gender and ethnicity. How do we ensure parity?

It definitely helps to have a really strong peer group in whatever part of the music industry you work in.

You need allies in your organisation to hear what you’re saying. You need to speak up to your line managers – but this can be a problem, especially when you’re junior or you’re still working up through the ranks.

We need to not only look at new recruitment, we need to look at the middle layer in terms of how we incubate talent.

And look to the executives that have done exceptionally well in the UK and globally to make a change. There are already some great initiatives; Power Up, run by the PRS Foundation, is a really good example.

You’ve talked very clearly about racism in the music industry before. Where do you think we are up to on the road to rooting that out?