Medical record

BCMS Pat Sharma

President’s Scholarship Recipients:

Outcomes in Solid Organ Transplant Patients Receiving Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors by Cyrus Rahmanian

Dysbiosis and Anxiety: Evidence for Association, Gut-Brain Axis Mechanisms and Intervention Strategies by Emily Shirk

INSIDE:

Respiratory Specialists is the region’s largest and most respected pulmonology group, staffed by board-certified pulmonologists and advanced practice providers with subspecialty expertise in pulmonary and sleep medicine. We offer comprehensive diagnostic evaluations, evidencebased treatment protocols, and longitudinal management for a wide range of respiratory and sleep disorders. Our collaborative approach ensures continuity of care and timely communication with referring providers.

• Sleep Evaluation (OSA, narcolepsy, insomnia,restless legs syndrome)

• Spirometry

• Biologics Treatment for Asthma

• Interstitial Lung Disease

• Occupational Lung Disease

• Pulmonary Hypertension

• Lung Nodule Surveillance

• Lung Cancer

• Robotic-Assisted Bronchoscopy

• Endobronchial Ultrasound

• Clinical Research Trials

Medical record

A Quarterly Publication

To provide news and opinion to support professional growth and personal connections within the Berks County Medical Society community.

Berks County Medical Society MEDICAL RECORD

D. Michael Baxter, MD, Editor

Editorial Board

D. Michael Baxter, MD

Lucy J. Cairns, MD

Daniel Forman, DO

Shannon Foster, MD

William Santoro, MD

Raymond Truex, MD

Beth E. Gerber, IOM

Berks County Medical Society Officers

Ankit Shah, MD President

Olapeju Simoyan, MD President Elect

Daniel Edwards, DO Treasurer

William Santoro, MD

Immediate Past President Secretary & Delegation Chair

Directors

Advocacy Chair: D. Michael Baxter, MD

Collegiality Chair: Pauletter Dreher, DO

Early Career Physician Chair: Caitlyn Moss, MD

Education Chair: Lucy Cairns, MD

Medical Record Editor: D. Michael Baxter, MD

Medical Student Chair: Peter Aziz (one-year term)

Residency Chair: Fatima Khalid, MD (one-year term)

Eve Kimball, MD

Jacob Lucas, DO

Amogh Nagol, student (one-year term)

Osadebamwen ‘Deb’ Osaghae, MD, resident (one-year term) Wei Shaw, DO

Mansi S. Vasconcellos, MD*, BCMS Alliance President Staff

Beth E. Gerber, IOM Executive Director

* designates non-voting member

Berks County Medical Society

2669 Shillington Rd., Suite 501, Sinking Spring, PA 19608 (610) 375-6555 • (610) 375-6535 (FAX) info@berkscms.org • www.berkscms.org

The opinions expressed in these pages are those of the individual authors and not necessarily those of the Berks County Medical Society. The ad material is for the information and consideration of the reader. It does not necessarily represent an endorsement or recommendation by the Berks County Medical Society.

Manuscripts offered for publication and other correspondence should be sent to 2669 Shillington Rd, Sinking Spring, PA 19608, Ste 501. The editorial board reserves the right to reject and/or alter submitted material before publication. The Berks County Medical Record (ISSN #0736-7333) is published four times a year by the Berks County Medical Society, 2669 Shillington Rd, Sinking Spring, PA 19608, Ste 501. Subscription $50.00 per year. Periodicals postage paid at Reading, PA, and at additional mailing offices.

POSTMASTER: Please send address changes to the Berks County Medical Record, 2669 Shillington Rd, Sinking Spring, PA 19608, Ste 501.

Berks County Medical Society –BECOME A MEMBER TODAY! Go to our website at www.berkscms.org and click on “Join Now” 27 Berks County Medical Society Historical Center Dedicated in the Reading Hospital

Advances in Urology: Newer Diagnostic & Treatment Options for Prostate Disease

Berks County Medical Society Alliance Celebrating 100 Years of Service

2025 BCMS Night at the Reading Fightin’ Phils

School Absenteeism and How Physicians Can Help

Student Vital Signs

Content Submission: Medical Record magazine welcomes recommendations for editorial content focusing on medical practice and management issues, and health and wellness topics that impact our community. However, we only accept articles from members of the Berks County Medical Society. Submissions can be photo(s), opinion piece or article. Typed manuscripts should be submitted as Word documents (8.5 x 11) and photos should be high resolution (300dpi at 100% size used in publication). Email your submission to info@berkscms.org for review by the Editorial Board. Thank YOU!

Ankit Shah, MD, FACEP, FAAEM, FAMIA President

Family. Friends. Community.

All three were on full display at the BCMS picnic at the R-Phils game. I had a great time chatting with physicians from across specialties—hospitalists, ophthalmologists, and many more. Just as energizing was connecting with the next generation—our residents and students. The enthusiasm was contagious (the free food didn’t hurt either!). The game was exciting, the weather couldn’t have been better, and I even got to throw out the first pitch (a little inside, but absolutely a strike!).

As you flip through this issue, pay special attention to the student articles. Every year I’m in awe of the incredible work “these kids” are producing—far beyond what I could have pulled off at their age (and maybe even today). Their creativity and perspective are inspiring, and their minds seem to operate on levels I couldn’t begin to grasp back when I was in training.

A quick reminder: BCMS and PA Med membership renewal is underway. Please renew at your earliest convenience and encourage colleagues in your practice who aren’t yet members to join. As a thank-you for your dedication to medicine here in Berks County, dues have been reduced for 2026.

Speaking of membership, I want to recognize a few groups that have consistently shown outstanding support with 100% membership among physicians:

• West Reading Radiology – 28 (100%)

• Digestive Disease Associates – 21 (100%)

• Eye Consultants of PA – 13 (100%)

• Reading Pediatrics – 8 (100%)

• Center for Urologic Care – 7 (100%)

• Berks Eye Physicians and Surgeons – 6 (100%)

• Reading Nephrology – 6 (100%)

• Arthritis and Osteoporosis Center – 5 (100%)

• Berks Radiation Oncology Associates – 4 (100%)

• ENT Head and Neck Specialists – 4 (100%)

A big thank-you to these groups for their ongoing support of BCMS and commitment to our county. Many other groups and solo physicians also have 100% membership, but the editors wisely stopped me from turning this into a 500-page booklet of shout-outs.

As summer winds down and fall begins, take a moment to breathe and remember: what you do matters. No matter the national discourse, your work is vital to our community, our families, and our colleagues. Thank you, as always, for your dedication to our patients, our hospitals, and each other.

by D. Michael Baxter, MD Editor, the Medical Record

Lucy Cairns, MD Past-Editor, the Medical Record

While it is uncommon for two Editors to write their comments in our “Editor’s Notes” section, these are uncommon times. As the two of us worked together to publish this Fall edition, we were once again impressed by the dedication and enthusiasm of our summer research students, the Pat Sharma Berks County Medical Society Scholars, and the Reading Hospital Summer Interns. In their efforts, we are reminded of at least two hundred years of science-based research which has advanced the practice of medicine and nearly doubled our life expectancy. With the development of vaccines, antibiotics and the latest advancements in genetics and immunology, our investment in science has led the way to astonishing success.

This has been a relentless march of progress, until now. In recent months we have seen unprecedented attacks on multiple pillars of the U.S. health care and public health systems by many of those officials—especially at the federal level—who fund and control medical research and health policy. There have been crippling cuts in funding and staffing at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and the disruption of the essential work of such voices of expertise as the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), with recognized experts being fired and replaced with others of dubious experience with political agendas to expound. Very recently two of our largest organizations of medical professionals, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), announced that they were rejecting certain vaccine guidelines by the CDC and making their own recommendations, an unprecedented move.

Simultaneously, some federal programs that fund health care and food security programs have been subject to major funding cuts and the tightening of eligibility criteria. These changes are predicted to result in large numbers of Americans losing their health

insurance and vital nutritional support. As the article in this issue by our local Helping Harvest community agency notes, this will have a significant negative impact on the lives of many people, our patients, in this community. The rise in the uninsured population from Medicaid cuts will have adverse consequences for the financial survival of hospitals and health systems, in addition to poorer health for the affected individuals.

Perhaps the most detrimental occurrence of all is the blatant attempt to undermine trust in the medical and public health professions by some who hold powerful positions in the federal government. Delegitimizing the work of established and respected experts in these fields opens the door to replacing the evidence-based approach to advancing healthcare and public health that has served our country well with one that serves a particular political ideology. The problem with allowing ideology to control healthcare decisions, rather than the best available evidence, is that outcomes are likely to miss the target we should all be aiming for, and do more harm than good. This should be unacceptable to a profession whose foundation depends on earning the trust of patients by putting their best interests above all.

At such times as this, one response would be to dismiss all of this and burrow deeper into our own work, doing the best we can with our own resources and abilities. However, if ever there was a time to stand for what we believe, for the oaths we have taken and the promises we have made to ourselves and to our patients, that time is now. There are avenues through our professional organizations and our elected representatives to demand accountability for truth and to ensure that fact-based science will guide our policy decisions and clinical choices. For over two hundred years this approach has led us to unimaginable advances in human health. Let us not now retreat.

Your new digital gateway to the latest WellSpan advances.

With articles, research updates and exclusive insights tailored for physicians, MacroScope is our new content platform to inform and inspire. We look forward to sharing medical innovations, clinical research and new technologies that will empower and inform your professional journey.

• Stay up to date: Keep abreast of the latest developments across various specialties.

• Gain insights: Benefit from expert analyses and studies that can directly impact your practice.

• Expand your network: Connect with other experts shaping the future of healthcare.

For another healthy dose of valuable medical content, subscribe to our companion publication. Complete the subscription form on MacroScope online for delivery to your home or office three times a year.

by Lucy J. Cairns, MD (retired)

The Pat Sharma President’s Scholarship Supporting the GenerationNext

In 2014 the Berks County Medical Society initiated a paid six-week summer program to provide local college students who have demonstrated an interest in medicine or public health with the opportunity to explore a topic of their choice under expert guidance, and to shadow clinicians in the office and operating room (OR). A cooperative relationship with the Reading Hospital’s Student Summer Internship has added greatly to the value of our program for the Pat Sharma scholars. This arrangement is currently enabled by Chief Academic Officer for Tower Health, Wei Du, MD. GME/UME Coordinators Ashley Morris and Sarah Saget do a superb job administering the hospital program and coordinating with our scholars.

Through this generous arrangement with Reading Hospital-Tower Health’s Academic Affairs team, our scholars are folded into the hospital program for the process of onboarding, have access to clinical shadowing and didactic sessions within the hospital, and join the hospital’s student interns in presenting their research work to a faculty panel at the end of the program. In turn, the BCMS is proud to

include abstracts submitted by the student researchers as a feature in this edition of the Medical Record. The variety and quality of the research being undertaken at Reading Hospital is reflected in these abstracts, which serve as a reminder of how fortunate we are to have in our community a medical institution focused on top-quality research and education, in addition to excellence in patient care.

Our community is also fortunate in the number of exceptionally capable young people who aspire to a career in medicine, looking to those of us who have gone before for encouragement and support. The applicants for the Pat Sharma President’s Scholarship appear more impressive with each passing year, presenting the selection committee with increasingly difficult choices.

Being able to offer a stipend to our scholars is a significant factor in attracting top applicants, made possible by the generous contributions of BCMS members to our Educational Trust. A large gift from retired vascular surgeon and past president of the BCMS, Pat Sharma, MD, in 2018 endowed this program with funds sufficient to support at least one student

per year. Another past president, retired neurosurgeon and current Medical Director of the Physicians Health Program of the Pennsylvania Medical Society Foundation, Raymond C. Truex Jr., MD, has supported additional Pat Sharma scholars in recent years, making the selection process a little less arduous. Our past and present scholars, and all the BCMS members who have found great reward in supporting this program through mentorships, owe Dr. Sharma and Dr. Truex a heartfelt debt of gratitude.

The 2025 Pat Sharma scholars are Cyrus Rahmanian and Emily Shirk. Cyrus graduated this year from Elizabethtown College in Lancaster, PA, with a major in Public Health. As an undergraduate student, among other achievements, Cyrus developed an interactive map using a Geographic Information System (GIS) displaying all U.S. thoracic transplant centers and their academic affiliation. This was designed for transplant teams to identify institutions capable of treating transplant patients who travel or relocate. With this mapping tool he also identified rural areas lacking adequate access to transplant services. Cyrus is currently a

student in a post-BA program at Drexel University that provides a pathway to medical school. He aspires to work in the field of transplant medicine and develop an effective treatment for chronic organ rejection.

Emily Shirk is completing her senior year as a biology major, with minors in public health and philosophy, at Drew University in Madison, NJ. In the 20212022 school year, Emily earned a 4.0 GPA in the Medical Health Professions Program through Berks Career & Technology Center, Penn State Berks, and Tower Health. In May of this year, she helped provide medical care to under-resourced communities in Panama with the Global Medical Brigade. Emily is strongly motivated by a desire to help shape the future of healthcare, possibly in a primary care role.

Emily and Cyrus were able to delve into topics of special interest to them—very complex topics—and produce research papers illustrating a good grasp of the subject thanks to close mentoring by BCMS members. Dr. Shoja S. Rahimian, a Medical Oncologist with the McGlinn Cancer Institute – Reading Hospital, guided Cyrus through his examination of the outcomes of Solid Organ Transplant Patients treated for cancer with immune checkpoint inhibitor drugs. Emily’s analysis of the evidence for connections between anxiety disorders and dysbiosis in the gut, and the intervention strategies that might be developed based on braingut microbiome interactions, was carried out with the generous aid of Dr. Eduardo Espiridion, Chair of the Department of Psychiatry at Reading Hospital-Tower Health, and Anna (Marianna) Bluestone, Registered Dietician with Reading Hospital. These clinicians repeatedly made time in their busy days to share their expertise with Emily and Cyrus.

The willingness of a long list of physicians, both within the Tower Health System and in independent practice, to allow our students to spend time shadowing them in the clinic and OR also contributes hugely to the value students

A New Face with a Clear Vision

Eye Consultants of Pennsylvania is excited to welcome Tianyu (Tom) Liu, MD, an award-winning, board-certified retinal specialist. Dr. Liu is fellowship-trained in vitreoretinal surgery and offers advanced care for conditions such as retinal detachments, diabetic retinopathy, and age-related macular degeneration. A graduate of the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine, Dr. Liu has earned numerous national honors and trained at some of the most respected programs in the country.

Whether you’re facing a complex retinal condition or seeking expert guidance on your eye health, you can trust Dr. Liu to provide compassionate, personalized care to protect and preserve your vision.

NOW ACCEPTING NEW PATIENTS AND PHYSICIAN REFERRALS IN WYOMISSING AND POTTSVILLE

Call 1-800-762-7132 or visit eyeconsultantsofpa.com today!

find in the Pat Sharma program. There is no replacement for the experience of oneon-one time with medical professionals for college students contemplating a career in healthcare. Space does not allow mention of the names of all these outstanding members of our Berks County medical community, but please know that you are much appreciated. The ongoing success of

the Pat Sharma President’s Scholarship is the result of a combined effort, and any BCMS member who would like to contribute financially or volunteer as a mentor is urged to join those of us who find this project invariably rewarding by contacting our Executive Director, Beth Gerber, at bgerber@ berkscms.org.

Outcomes in Solid Organ Transplant Patients Receiving Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

Lucy J. Cairns, MD, Berks County Medical Society

INTRODUCTION

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) as a form of immunotherapy have changed the standards of cancer care in numerous indications. By targeting pathways in T-cells to enhance anti-tumor responses, ICIs have shown significant efficacy (Doroshow 2021). It is estimated that 44% of newly diagnosed cancer patients are eligible for ICIs (Haslam, 2025). Cancer is the second leading cause of death in transplant patients (Saleem, 2025).

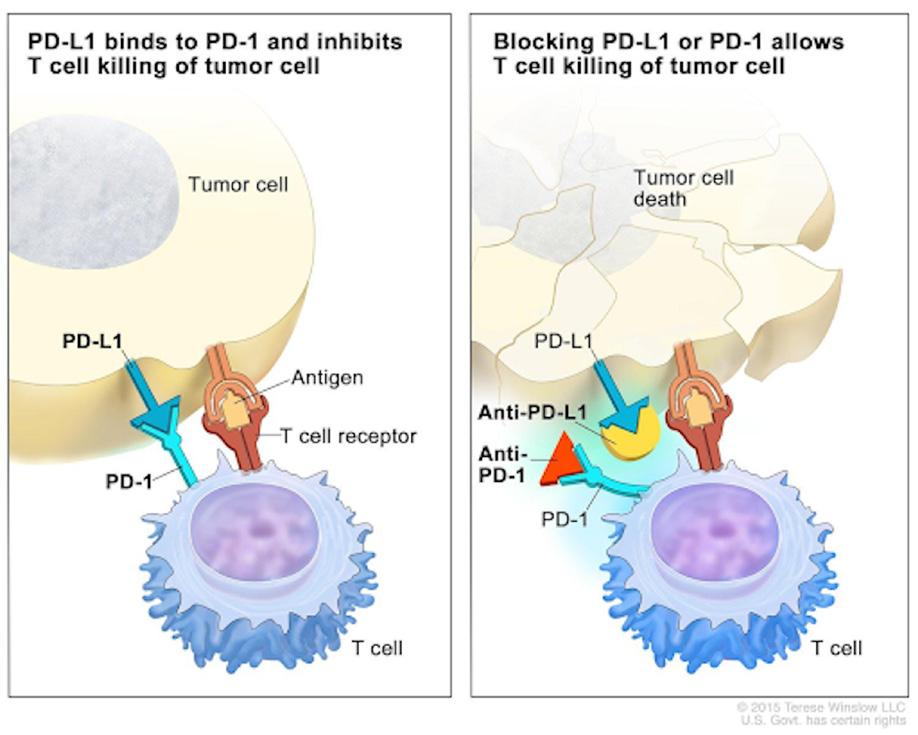

Among the most common ICIs are programmed cell death-ligand (PD-L1) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4). Common ICIs targeting the PD-1 receptor are nivolumab, pembrolizumab, and cemiplimab. Common PD-L1 inhibitors include atezolizumab, avelumab, and durvalumab. Tumor cells can express the PD-L1 protein, which binds to the PD-1 receptor to negatively regulate the T-cell and prevent it from attacking the tumor cell (Figure 1, NCI Winslow, 2022). ICI therapy blocks this interaction, allowing the T-cell to recognize and attack the tumor cell.

ICI as a cancer treatment modality, however, presents concerns when treating transplant patients who are on immunosuppressants to stop T-cell mediated rejection. T-cells are the main cause of allograft rejection in transplant patients, due to allorecognition of foreign antigens causing the T-cells to attack the transplanted organ

(Issa, 2010). Immune checkpoint inhibitors can inadvertently activate the body’s immune response towards T-cell mediated lysis of graft cells in the transplanted organ, similar to acute allograft rejection (Justiz, 2024). Most commonly, this can present challenges for kidney transplant patients, who represent the largest population in solid organ transplants. This paper explores the potential challenges of using immune checkpoint inhibitors in solid organ transplant recipients with cancer and highlights clinical outcomes and future directions in the field of immunology for this population.

TRANSPLANT IMMUNOLOGY

To reduce the risk of allograft rejection, Solid Organ Transplant Recipients (SOTR) take medication to suppress their immune system. A rejection episode occurs when the patient’s own body is producing T-cells that recognize the donor organ as foreign and start attacking it, which can lead to organ failure. The two most common types of rejection found in SOTR are acute rejection and chronic rejection. Acute rejection typically occurs within days or months after the transplantation and involves the body recognizing the donor organ as foreign in a T-cell mediated response. This form of rejection is the most common in SOTR, with an incidence rate of 50% to 70% within the first few months of the transplant (Justiz, 2024). Acute rejection is commonly treated with steroids (Murakami, 2021). Chronic rejection can occur further down the road, including months or years after transplantation. This form of

rejection involves inflammation and an immune response against the transplanted organ. Chronic rejection can be managed by immunosuppressants, but there is currently no cure and it is not fully understood (Justiz, 2024).

KIDNEY TRANSPLANT RECIPIENTS

Kidney transplant Patients Receiving Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

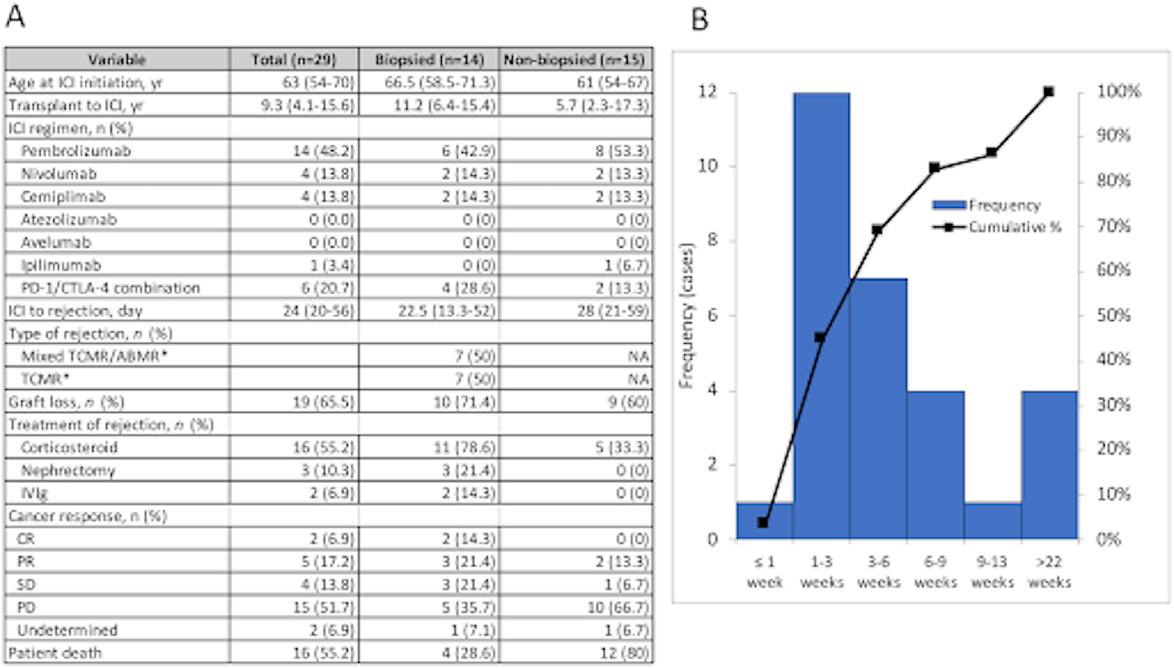

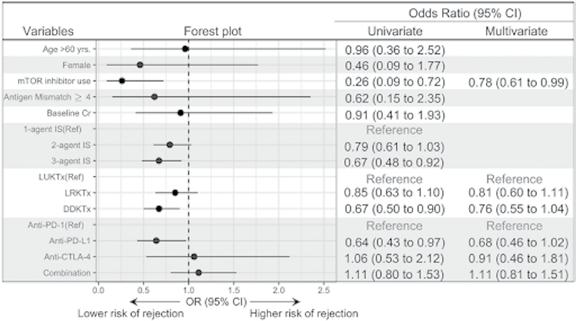

A multicenter study was conducted between 2010 and 2020 across 23 institutions involving kidney transplant recipients receiving ICI. There were 69 participants in this retrospective cohort study receiving immunotherapy for cancer. The most common cancers in the cohort were squamous cell carcinoma, with 24 cases, and melanoma with 22 (Murakami, 2021). After the 69 patients received immunotherapy, 29 of them developed acute rejection. Sixteen of the 29 patients who developed acute rejection were treated with high dose intravenous corticosteroids. Forty-five of the patients changed their immunosuppressive medication prior to starting immunotherapy and the most common change was from CNI to mTORi, making up 15 of the 45 changes (Murakami). Fourteen patients also increased their corticosteroids. Fourteen of the 29 patients with acute rejection were on pembrolizumab, a PD-1 inhibitor. One of the 29 patients was on ipilimumab, a CTLA-4 inhibitor, and 6 patients were on a combination of PD-1/CTLA4 regimens (Murakami, 2021). Anti-CTLA-4 immunotherapy resulted in a higher risk of allograft rejection compared to anti PD-L1.

Kidney Transplant Patients Not Receiving Immune Checkpoint

Inhibitors

There were 37 transplant patients who underwent treatment for cancer who did not receive immunotherapy. The most common cancers in this cohort were squamous cell carcinoma, with 23 cases, and melanoma with 14. Twenty of the 23 patients with cSCC received systemic cancer-directed therapy. Twelve of those 20 patients received cetuximab.

Melanoma Cohort

The 22 patients receiving ICI who were diagnosed with melanoma had a graft rejection rate of 54.5% compared to 7.1% in the non ICI group (n=14) p<0.01 (Murakami, 2021). The response rate of the cancer to ICI was 40.0%. One patient had a complete response to the immunotherapy and 7 had partial responses. One achieved stable disease, and 11 patients had progressive disease. Eleven of the patients were treated with pembrolizumab and 8 were treated with a combination therapy.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cohort

There were 24 patients who received ICI and 23 non-ICI treatment for cSCC. The rejection rate was much greater in the ICI group with 9 (37.5%) of the patients developing rejection compared to just 1 (4.3%) patient in the non-ICI group. The tumors of 2 patients on ICI had a complete response to the treatment and 6 had a partial response. Ten (41.7%) patients in the ICI group had progressive disease while 18 (78.3%) in the non-ICI group had progressive disease.

LUNG & HEART TRANSPLANT RECIPIENTS

An analysis of 140 studies involving SOTR receiving ICIs included 343 transplant patients receiving ICIs. Among the 343 were 5 lung transplant patients and 18 heart transplant patients. The study concluded that 2 (40%) of the lung transplant patients experienced graft rejection and 7 (38.9%) of heart transplant patients receiving ICIs had graft rejection (Saleem, 2025).

Patient Response

Of the 343 patients on ICI, 116 (33.8%) of them developed rejection. Sixty-nine (59.5%) of those patients experienced rejectioninduced graft loss (Saleem, 2025). The tumor responses (n=303) for patients were the following: 49 (16.2%) had complete response, 65 (21.5%) had partial response, 48 (15.8%) had stable disease, continued on next page >

and 138 (45.5%) had progressive disease. Fifty-three patients were surveyed on their quality of life after receiving ICIs. Twenty-six (49%) said their quality of life improved while 27 (51%) said their quality of life worsened.

OUTCOMES

Forty-two percent of kidney transplant patients developed acute rejection, 65% of whom did not recover and had graft loss and needed dialysis. While treatment with ICIs is associated with high acute rejection rates, it also appears to improve the odds of a positive tumor response. Five of the patients on an ICI had a complete response to the treatment, 15 had a partial response, and 11 had stable disease, for a total of 31 patients experiencing a positive tumor response to the immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment for their cancer. Thirty-four (49.3%) of the patients treated with an ICI experienced progressive disease, compared with 28 (75.7%) of those not treated with an ICI. This shows that ICI treatment increases the odds of a positive response when used to treat cancer in transplant patients. Unfortunately, it also increases the risk of acute rejection. The transplant patient group which did not receive ICIs had an acute rejection rate of just 5.4%, compared to a 42% acute rejection rate in the ICI-treated group (Murakami, 2021).

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS

The average time from transplantation of the donor kidney to ICI treatment was 9 years in the cohort study (Murakami, 2021). The average time from transplant to diagnosis was 12 years for cSCC and 7.7 years for melanoma. The average life expectancy of a kidney transplant recipient can vary due to numerous reasons, such as whether the organ was a living donor kidney (15-20 years) or deceased donor kidney (10-15 year years). While immune checkpoint inhibitors appear to be an effective cancer treatment, their use in SOTR patients greatly increases the risk of developing acute rejection. It is important to have discussions between the patient’s multidisciplinary care teams and the patient to decide if treatment with ICI is worth pursuing to treat their cancer. It is important to note that transplant patients with cancer are not eligible for a re-transplant if they still have cancer, a reality which may affect the decision making on whether to use ICI or not. It is also important to consider which organ is transplanted, as there is no long-term option for managing lung failure or heart failure, while there are options like dialysis for kidney patients who have graft-induced organ failure. Physicians may be more inclined to aggressively treat a cancer with ICI in a patient with a transplanted kidney, knowing that they can go on dialysis if there is organ failure.

DISCUSSION

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are an effective treatment for attacking cancer, but their use also results in a high risk of rejection among transplant patients. This raises ethical concerns with care teams as they attempt to balance the risk vs reward. There are hundreds of known biomarkers, and new ones being discovered, which may lead to new treatments being developed that may include safer options for transplant patients. (Chronic rejection still has no cure, and it may be worthwhile to look into the use of the PD-1 and PD-L1 mechanism in donor organs to combat T-cell mediated rejection.) At the end of the day, the decision is up to the patient. Care teams can educate the patient using these studies and strategize to mitigate the risk of rejection and adjust the patient’s immunosuppressive regimen.

References

Carlino, M. S., Larkin, J., & Long, G. V. (2021). Immune checkpoint inhibitors in melanoma. Lancet (London, England), 398(10304), 1002–1014. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01206-X

Doroshow, D. B., Bhalla, S., Beasley, M. B., Sholl, L. M., Kerr, K. M., Gnjatic, S., Wistuba, I. I., Rimm, D. L., Tsao, M. S., & Hirsch, F. R. (2021). PD-L1 as a biomarker of response to immune-checkpoint inhibitors. Nature reviews. Clinical oncology, 18(6), 345–362. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-02100473-5

Issa, F., Schiopu, A., & Wood, K. J. (2010). Role of T cells in graft rejection and transplantation tolerance. Expert review of clinical immunology, 6(1), 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1586/eci.09.64

Murakami, N., Mulvaney, P., Danesh, M., Abudayyeh, A., Diab, A., Abdel-Wahab, N., Abdelrahim, M., Khairallah, P., Shirazian, S., Kukla, A., Owoyemi, I. O., Alhamad, T., Husami, S., Menon, M., Santeusanio, A., Blosser, C. D., Zuniga, S. C., Soler, M. J., Moreso, F., Mithani, Z., … Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Solid Organ Transplant Consortium (2021). A multi-center study on safety and efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer patients with kidney transplant. Kidney international, 100(1), 196–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2020.12.015

Naimi, A., Mohammed, R. N., Raji, A., Chupradit, S., Yumashev, A. V., Suksatan, W., Shalaby, M. N., Thangavelu, L., Kamrava, S., Shomali, N., Sohrabi, A. D., Adili, A., Noroozi-Aghideh, A., & Razeghian, E. (2022). Tumor immunotherapies by immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs); the pros and cons. Cell communication and signaling : CCS, 20(1), 44. https://doi. org/10.1186/s12964-022-00854-y

Nguyen, L. S., Ortuno, S., Lebrun-Vignes, B., Johnson, D. B., Moslehi, J. J., Hertig, A., & Salem, J. E. (2021). Transplant rejections associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: A pharmacovigilance study and systematic literature review. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990), 148, 36–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2021.01.038

Saleem, N., Wang, J., Rejuso, A., Teixeira-Pinto, A., Stephens, J., Wilson, A., Kieu, A., Gately, R., Boroumand, F., Chung, E., Bonevski, B., Carlino, M., Carroll, R., Lim, W., Craig, J., Murakami, N., & Wong, G. (2025). Outcomes of Solid Organ Transplant Recipients With Advanced Cancers Receiving Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. JA

Simon, S., & Labarriere, N. (2017). PD-1 expression on tumor-specific T cells: Friend or foe for immunotherapy?. Oncoimmunology, 7(1), e1364828. https://doi.org/10.1080/2162402X.2017.1364828

Tabrizian, P., Abdelrahim, M., & Schwartz, M. (2024). Immunotherapy and transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of hepatology, 80(5), 822–825. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2024.01.011

Tang, Q., Chen, Y., Li, X., Long, S., Shi, Y., Yu, Y., Wu, W., Han, L., & Wang, S. (2022). The role of PD-1/PD-L1 and application of immunecheckpoint inhibitors in human cancers. Frontiers in immunology, 13, 964442. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.964442

Tejani, A., & Emmett, L. (2001). Acute and chronic rejection. Seminars in nephrology, 21(5), 498–507. https://doi.org/10.1053/snep.2001.24945

Vera, R. (no date) WCN24-1341 prevalence of rejection in kidney transplant patients at the Hospital de Clínicas - Kidney International Reports. Available at: https://www.kireports.org/article/S2468-0249(24)01059-3/fulltext

Specializing in the diagnosis and treatment of ALL neck and back disorders.

ALL SURGERY PERFORMED IN BERKS COUNTY

• Pain Management

• Physical Therapy

• Epidural Injections

• Spinal Surgery

2607 Keiser Blvd, Suite 200, Wyomissing, PA 19610 484-509-0840

Evidence for Association, Gut-Brain Axis Mechanisms, and Intervention Strategies

BCMS Pat Sharma President’s Scholarship Recipient

Preceptors: Eduardo D. Espiridion, MD, Chair, Dept. of Psychiatry, Reading Hospital/Tower Health

Marianna Bluestone, Registered Dietician

Eve Kimball, MD, FAAP

INTRODUCTION:

Approximately one in five adults in the United States experience symptoms of an anxiety disorder (28). Characterized by excessive worrying and anxious thoughts that do not subside, an anxiety disorder can be debilitating and interfere with normal social and occupational life. The cause of anxiety is not well understood. Genetics, brain chemistry, and environmental stress may all play a role in the development of this psychiatric disorder (29). In recent years, research exploring the various connections between the brain and gut, also known as the gut-brain axis, has illustrated a potential link between the resident microorganisms in the large intestine and the host’s mental health (6). The microbiomegut-brain axis refers to the two-way communication between the gut microflora and the brain via neuronal signaling, hormones, chemical messengers, and the immune system. A condition that elucidates this connection well is irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Patients with IBS are 3 times more likely to have anxiety compared to healthy individuals, highlighting that abnormalities in the gut may impact mental health; however, this relationship is not well understood (26). The aim of this article is to examine the relationship between gut microbiota composition and anxiety, explore some possible mechanisms that may contribute to this relationship, and evaluate possible gut interventions as a means to improve anxiety symptoms.

GUT MICROBIOME

By definition, the gut microbiome refers to the collection of bacteria and other microorganisms that inhabit the gastrointestinal tract, spanning from mouth to anus. However, when people refer to the “gut microbiome,” they are often referencing the bacterial species residing in the colon, which contains approximately 70% of the body’s total microbial population (16). The dominant phyla of the colon are Firmicutes (Gram-positive) and Bacteroidetes (Gram-negative). These bacteria have a commensal relationship with their human host, meaning that they benefit from living in the rich environment of the colon, and the human host simultaneously benefits from their activity.

The primary role of a healthy gut microbiome is to break down carbohydrates that are indigestible to the host, also known as soluble fiber, to produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). Gut bacteria can also break down proteins, produce vitamins K and B, and metabolize drugs and other foreign substances. The gut microbiome also plays an integral role in immune regulation by outcompeting pathogenic bacteria and stimulating immune responses of host cells to prevent pathogenic colonization. Finally, a healthy gut microbiome is also responsible for maintaining the integrity of the gut barrier by promoting tight epithelial junctions, preventing host epithelial cell loss, and modulating host signaling

Dysbiosis refers to a disturbance in the microbial equilibrium due to an imbalance of flora, changes in flora metabolism, or changes in their spatial distribution (8). Dysbiosis can involve a loss of beneficial organisms, a growth of harmful organisms, and/or an overall loss of microbial diversity. In addition to IBS, scientists have also found connections between dysbiosis and obesity, allergies, Type 1 diabetes, autism, and colorectal cancer.

DYSBIOSIS AND ANXIETY

Multiple studies have shown that people with anxiety tend to have a different microbiota composition compared to those without anxiety. A 2025 systematic review of 8 cross-sectional studies analyzing human fecal samples found that the gut microbiome of patients with diagnosed anxiety disorders was significantly different from that of healthy controls. Decreases in Faecalibacterium, Coprococcus, and Eubacterium were observed, all of which are genera within the Firmicutes phylum. Furthermore, in some studies, individuals who were actively experiencing anxiety symptoms had lower levels of Faecalibacterium compared to those who had recovered from anxiety disorders, suggesting that the microbiome may shift alongside changes in mental health. Patients with generalized anxiety disorder were also reported to have increased levels of Bacteroides, Ruminococcus gnavus, and Fusobacterium (2) .

Another cross-sectional study conducted on gastrointestinal clinic patients found significant differences in the microbiome based on levels of anxiety. Similar to the 2025 study, the researchers found that patients who scored higher on anxiety scales had less Faecalibacterium and Bifidobacterium. Bifidobacterium belongs in the phyla Actinobacteria, which was, in general, less represented in anxious microbiomes. Anxious patients also showed a greater abundance of Clostridioides and Bacteroides (14)

POSSIBLE MECHANISMS

There are a variety of gut-brain axis mechanisms that may explain microbiota imbalances manifesting as anxiety symptoms. Faecalibacterium, Coprococcus, and Eubacterium, all genera shown to be depleted in anxious patients across multiple studies, are major SCFA-producers within the gut, specifically of butyrate (20, 25, 22) . SCFAs within the gut have many beneficial properties, including induction of enteric serotonin production and maintenance of tight junctions. These properties of SCFAs may help to explain the relationship between dysbiosis and anxiety. Animal models have shown that supplementation with SCFAs helps to reduce anxiety symptoms in response to psychosocial stressors; however, this has not been shown in humans yet (30) .

Within the gut, SCFAs stimulate specialized host cells called enterochromaffin (EC) cells, which are responsible for producing 90-95% of the body’s serotonin. In a two-step enzymatic reaction, EC cells convert tryptophan into serotonin using the enzymes tryptophan hydroxylase 1 (TPH1) and aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (19). Mouse studies have shown that the gut microbiome is essential for serotonin synthesis, as germ-free mice, continued on next page >

Do you have patients with:

• Chronic Headaches

• Tinnitus

• Jaw Pain

• Insomnia

• Ear Pain without signs of infection

• Dizziness

• Clicking, popping, or grating in the jaw joint

• Limited jaw opening or locking

• Swallowing difficulty

• Snoring

• Pain when chewing

• Sleep issues

• Facial pain

• Neck pain or stiffness

• Tired jaws

• CPAP Intolerance

If so, they may be suffering from TMJ Dysfunction and/or Sleep Disordered Breathing, such as snoring and obstructive sleep apnea. We offer comprehensive diagnosis and treatment. Our many years of experience have resulted in a high rate of successful outcomes.

Our philosophy involves a conservative, non-surgical, non-pharmaceutical approach to management with an emphasis on multidisciplinary care.

or mice lacking any microbiome, exhibit significantly reduced TPH1 expression in the colon, indicating impaired serotonin production. These germ-free mice also displayed increased anxietylike behaviors (24). Enteric serotonin acts on the vagus nerve, which is the main nerve connecting the gut to the brain (15). In a study looking at anxious and depressive behaviors of mice based on their gut microbiota, the patterns studied were not seen when the mouse’s vagus nerve was cut, showing that many anti-anxiety properties of the gut-microbiota are vagus nerve-dependent (5). Vagus nerve activity has anti-anxiety effects: it activates the parasympathetic nervous system and suppresses the hypothalamic pituitary axis (HPA), which is associated with cortisol release (23). Overall, a lack of SCFA-producing bacteria could lead to anxiety via decreased SCFAinduced vagus nerve activity.

In addition to depletion of serotonin, a lack of SCFAs due to dysbiosis may also lead to increased free tryptophan. Tryptophan that is not converted into serotonin can be metabolized through the kynurenine pathway, and since both serotonin and kynurenine are derived from the same precursor—tryptophan—it is plausible that decreased SCFAs and associated decreased serotonin production could push tryptophan down the kynurenine pathway (10). Similarly, butyrate, which may be depleted in anxious patients, suppresses the enzyme that converts tryptophan into kynurenine, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) (21). This may also explain the beneficial role of SCFAs on serotonin production. In a study of social anxiety disorder, subjects with anxiety had significant alterations in their tryptophan-kynurenine pathway (3). Researchers suggest that KYNA, a metabolite of kynurenine that was higher in anxious patients, may impact glutamate signaling, resulting in anxiety. Other research suggests that quinolinic acid, another metabolite of kynurenine, is also associated with anxiety (18). The combination of decreased serotonin and increased neuroactive kynurenine metabolites may both contribute to worsened host mental health.

Butyrate and other SCFAs also help to maintain the tight junctions between gut epithelial cells. Animal models have shown that germ-free mice have increased intestinal permeability; however, this permeability could be reversed with supplementation of SCFAs and SCFA-producing bacteria (4). Increased permeability of the gut epithelium allows gut microbiota and bacterial products, like lipopolysaccharide (LPS), to enter the bloodstream, causing cytokine production and low-grade inflammation. Additionally, some research suggests that LPS may directly contribute to gut permeability (7). It is important to note that some species that were particularly high in anxious people, like Bacteroides and Fusobacterium, produce LPS, which could contribute to more inflammation. These inflammatory cytokines can act locally, similar to serotonin, or unlike serotonin, they can cross the blood-brain barrier and act directly on neurons in the brain (13). Low-grade inflammation and elevated cytokine levels are associated with increased anxiety by disrupting neurotransmitter systems, activating microglia, and impairing brain circuits involved in emotional regulation (13). This condition is more commonly referred to as “leaky gut.” A 2018 study found correlations between anxiety and circulating LPS, as well as Zonulin and FABP2, two proteins that indicate leaky gut syndrome in subjects that did not have gastrointestinal disorders (27). This shows that anxious patients may be experiencing “leaky gut” without the common accompanying gastrointestinal disorders. Additionally, inflammatory cytokines activate IDO which may also contribute to anxious symptoms via the tryptophan-kynurenine pathway (18) .

Various other pathways of the microbiome gut-brain axis may explain connections to anxiety, including GABA, hydrogen sulfide, and other immune functions; however, due to the scope of this article, they are not discussed here (6)

Connecting Berks County to Addiction Resources

Local Treatment and Recovery Resources

Free NARCAN Kits

Free Medication Lock Boxes

Community and School Education

Free Tobacco Cessation Classes

INTERVENTIONS

Treatment of dysbiosis often involves probiotics, prebiotics, and diets high in fiber. Understanding these treatments as a means to mitigate anxiety symptoms could be beneficial for many patients, as dietary changes and pre- and probiotic supplements tend to have less negative side effects than conventional anxiety treatments such as serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) (11) .

Unfortunately, the species that are depleted in anxious patients, such as Faecalibacterium, Eubacterium, and Coprococcus, are challenging to culture into probiotics, as they are obligate anaerobes and sensitive to oxygen (20, 25, 22). There is ongoing research to develop “next-generation” probiotics by culturing butyrate-producing anaerobic bacteria, such as Faecalibacterium, in combination with sulfate-reducing bacteria. However, this work is still in early stages and has not yet led to commercially available products (17)

Consuming more dietary fiber could be a way to increase SCFAs and SCFA-producing bacteria to alleviate dysbiosis related to anxiety. While limited research is currently available on the relationship between high dietary fiber intake and anxiety, there are a few promising cross-sectional studies that together reveal a significant inverse relationship between fiber consumption and . Fiber intake in this meta-analysis was based on

(610) 376-8669 cocaberks.org

fiber supplementation and self-reported diet. However, at this time no randomized controlled trials have shown that fiber consumption can be an efficacious treatment for anxiety. Prebiotics, a specific type of fermentable fiber, have also been associated with improved anxiety symptoms. A randomized controlled trial has shown that a diet naturally rich in prebiotic fibers may support mood, reduce anxiety and stress, and improve sleep in adults, while probiotic supplements or combinations of pre- and probiotics did not show the same effect (9). This shows that dietary changes tend to be more impactful than supplements. More research, specifically randomized controlled trials, should be conducted to study the impact of dietary fiber intake, probiotics, and prebiotics, as these treatments have far less negative symptoms compared to conventional anti-anxiety medications.

CONCLUSION

This review aimed to explore the relationship between dysbiosis and anxiety, potential pathways of the gut-brain axis, and interventions. Anxious patients tended to have decreased Faecalibacterium, Eubacterium, and Coprococcus and increased Bacteroides and Fusobacterium. Potential pathways explaining this association involving reduced SCFAs, decreased enteric serotonin, increased kynurenine metabolites, decreased vagus nerve stimulation, continued on next page >

and inflammation were not linear. Increased dietary fiber and prebiotics may show promise for alleviating anxiety.

While some preliminary research has shown a connection between dysbiosis and anxiety, and some proposed mechanisms have been explained above, it is important to note that the dysbiosis may not be a cause of anxiety but rather an effect. The gut-brain axis is a bidirectional pathway in which the gut is also influenced by the brain, which was not explored in this paper. Many studies show that even very small and short-lasting stressors can change microbial concentrations (12). The association between dysbiosis and anxiety is important to explore further, as definitive and direct pathways have yet to be determined. Additionally, the research that has been cited may be limited by small sample sizes or animal models. Larger-scale cross-sectional and experimental studies of humans should be conducted in order to better understand this convoluted relationship. The gut-brain axis is a fascinating topic with many facets that have yet to be explored, but with more research scientists may be able to find efficacious and low-risk treatments for anxiety disorders.

Emily Shirk is a senior at Drew University in Madison, New Jersey. Her major field of study is Biology with minors in Public Health and Philosophy. Her career plan is to apply to medical school.

References

1. Aslam, H., Lotfaliany, M., So, D., Berding, K., Berk, M., Rocks, T., Hockey, M., Jacka, F. N., Marx, W., Cryan, J. F., & Staudacher, H. M. (2024). Fiber intake and fiber intervention in depression and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies and randomized controlled trials. Nutrition reviews, 82(12), 1678–1695. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/ nuad143

2. Butler, M. I., Kittel-Schneider, S., Wagner-Skacel, J., Mörkl, S., & Clarke, G. (2025). The Gut Microbiome in Anxiety Disorders. Current psychiatry reports, 27(5), 347–361. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-025-01604-w

3. Butler, M. I., Long-Smith, C., Moloney, G. M., Morkl, S., O’Mahony, S. M., Cryan, J. F., Clarke, G., & Dinan, T. G. (2022). The immune-kynurenine pathway in social anxiety disorder. Brain, behavior, and immunity, 99, 317–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2021.10.020

4. Braniste, V., Al-Asmakh, M., Kowal, C., Anuar, F., Abbaspour, A., Tóth, M., Korecka, A., Bakocevic, N., Ng, L. G., Kundu, P., Gulyás, B., Halldin, C., Hultenby, K., Nilsson, H., Hebert, H., Volpe, B. T., Diamond, B., & Pettersson, S. (2014). The gut microbiota influences blood-brain barrier permeability in mice. Science translational medicine, 6(263), 263ra158. https://doi. org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3009759

5. Bravo, J. A., Forsythe, P., Chew, M. V., Escaravage, E., Savignac, H. M., Dinan, T. G., Bienenstock, J., & Cryan, J. F. (2011). Ingestion of Lactobacillus strain regulates emotional behavior and central GABA receptor expression in a mouse via the vagus nerve. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108(38), 16050–16055. https://doi.org/10.1073/ pnas.1102999108

6. Carabotti, M., Scirocco, A., Maselli, M. A., & Severi, C. (2015). The gutbrain axis: interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. Annals of gastroenterology, 28(2), 203–209. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih. gov/articles/PMC4367209/

7. Chelakkot, C., Ghim, J. & Ryu, S.H. Mechanisms regulating intestinal barrier integrity and its pathological implications. Exp Mol Med 50, 1–9 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-018-0126-x

8. DeGruttola, A. K., Low, D., Mizoguchi, A., & Mizoguchi, E. (2016). Current Understanding of Dysbiosis in Disease in Human and Animal Models. Inflammatory bowel diseases, 22(5), 1137–1150. https://doi.org/10.1097/ MIB.0000000000000750

9. Freijy, T. M., Cribb, L., Oliver, G., Metri, N.-J., Opie, R. S., Jacka, F. N., Hawrelak, J. A., Rucklidge, J. J., Ng, C. H., & Sarris, J. (2023). Effects of a high-prebiotic diet versus probiotic supplements versus synbiotics on adult mental health: The “Gut Feelings” randomised controlled trial. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 16, 1097278. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2022.1097278

10.Gao, K., Mu, C. L., Farzi, A., & Zhu, W. Y. (2020). Tryptophan Metabolism: A Link Between the Gut Microbiota and Brain. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md.), 11(3), 709–723. https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/ nmz127

11. Garakani, A., Murrough, J. W., Freire, R. C., Thom, R. P., Larkin, K., Buono, F. D., & Iosifescu, D. V. (2020). Pharmacotherapy of Anxiety Disorders: Current and Emerging Treatment Options. Frontiers in psychiatry, 11, 595584. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.595584

12. Geng, S., Yang, L., Cheng, F., Zhang, Z., Li, J., Liu, W., Li, Y., Chen, Y., Bao, Y., Chen, L., Fei, Z., Li, X., Hou, J., Lin, Y., Liu, Z., Zhang, S., Wang, H., Zhang, Q., Wang, H., Wang, X., … Zhang, J. (2020). Gut Microbiota Are Associated With Psychological Stress-Induced Defections in Intestinal and BloodBrain Barriers. Frontiers in microbiology, 10, 3067. https://doi.org/10.3389/ fmicb.2019.03067

13. Guo, B., Zhang, M., Hao, W. et al. Neuroinflammation mechanisms of neuromodulation therapies for anxiety and depression. Transl Psychiatry 13, 5 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-022-02297-y

14. Hazan, S., von Guttenberg, M., Vidal, A. C., Spivak, N. M., & Bystritsky, A. (2024). A Convenience Sample Looking at Microbiome Differences Between Anxious and Non-Anxious Patients in a GI Clinic. Gastroenterology Insights, 15(4), 1054-1063. https://doi.org/10.3390/gastroent15040072

15. Hwang, Y. K., & Oh, J. S. (2025). Interaction of the Vagus Nerve and Serotonin in the Gut-Brain Axis. International journal of molecular sciences, 26(3), 1160. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26031160

16. Jandhyala, S. M., Talukdar, R., Subramanyam, C., Vuyyuru, H., Sasikala, M., & Nageshwar Reddy, D. (2015). Role of the normal gut microbiota. World journal of gastroenterology, 21(29), 8787–8803. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg. v21.i29.8787

17. Khan, M. T., Duncan, S. H., Stams, A. J. M., van Dijl, J. M., Flint, H. J., & Harmsen, H. J. M. (2023). Synergy and oxygen adaptation for development of next-generation probiotics. Nature, 619(7972), 743–750. https://doi. org/10.1038/s41586-023-06378-w

18. Kim, Y. K., & Jeon, S. W. (2018). Neuroinflammation and the ImmuneKynurenine Pathway in Anxiety Disorders. Current neuropharmacology, 16(5), 574–582. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159X15666170913110426

19. Liu, N., Sun, S., Wang, P., Sun, Y., Hu, Q., & Wang, X. (2021). The Mechanism of Secretion and Metabolism of Gut-Derived 5-Hydroxytryptamine. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(15), 7931. https://doi. org/10.3390/ijms22157931

20. Martín, R., Rios-Covian, D., Huillet, E., Auger, S., Khazaal, S., Bermúdez-Humarán, L. G., Sokol, H., Chatel, J. M., & Langella, P. (2023). Faecalibacterium: a bacterial genus with promising human health applications. FEMS microbiology reviews, 47(4), fuad039. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsre/ fuad039

21. Martin-Gallausiaux, C., Larraufie, P., Jarry, A., Béguet-Crespel, F., Marinelli, L., Ledue, F., Reimann, F., Blottière, H. M., & Lapaque, N. (2018). Butyrate Produced by Commensal Bacteria Down-Regulates Indolamine 2,3-Dioxygenase 1 (IDO-1) Expression via a Dual Mechanism in Human Intestinal Epithelial Cells. Frontiers in immunology, 9, 2838. https:// doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.02838

22. Notting, F., Pirovano, W., Sybesma, W., & Kort, R. (2023). The butyrateproducing and spore-forming bacterial genus Coprococcus as a potential biomarker for neurological disorders. Gut microbiome (Cambridge, England), 4, e16. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmb.2023.14

23. Richer, R., Zenkner, J., Küderle, A., Rohleder, N., & Eskofier, B. M. (2022). Vagus activation by Cold Face Test reduces acute psychosocial stress responses. Scientific reports, 12(1), 19270. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-23222-9

24. Roussin, L., Gry, E., Macaron, M., Ribes, S., Monnoye, M., Douard, V., Naudon, L., & Rabot, S. (2024). Microbiota influence on behavior: Integrative analysis of serotonin metabolism and behavioral profile in germ-free mice. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, 38(11), e23648. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.202400334R

25. Ryu, S. W., Kim, J. S., Oh, B. S., Choi, W. J., Yu, S. Y., Bak, J. E., Park, S. H., Kang, S. W., Lee, J., Jung, W. Y., Lee, J. S., & Lee, J. H. (2022). Gut Microbiota Eubacterium callanderi Exerts Anti-Colorectal Cancer Activity. Microbiology spectrum, 10(6), e0253122. https://doi.org/10.1128/ spectrum.02531-22

26. Staudacher, H. M., Black, C. J., Teasdale, S. B., Mikocka-Walus, A., & Keefer, L. (2023). Irritable bowel syndrome and mental health comorbidityapproach to multidisciplinary management. Nature reviews. Gastroenterology & hepatology, 20(9), 582–596. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-023-00794-z

27. Stevens, B. R., Goel, R., Seungbum, K., Richards, E. M., Holbert, R. C., Pepine, C. J., & Raizada, M. K. (2018). Increased human intestinal barrier permeability plasma biomarkers zonulin and FABP2 correlated with plasma LPS and altered gut microbiome in anxiety or depression. Gut, 67(8), 1555–1557. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314759

28. Terlizzi, E. P., & Zablotsky, B. (2024). Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression Among Adults: United States, 2019 and 2022. National health statistics reports, (213), CS353885. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39591466/

29. U.S. National Library of Medicine. (2024). Anxiety. MedlinePlus. https:// medlineplus.gov/anxiety.html

van

O’Sullivan, O., Clarke, G., Stanton, C., Dinan, T. G., & Cryan, J. F.

Short-chain fatty acids: microbial metabolites that alleviate stress-induced brain-gut axis alterations. The Journal of physiology, 596(20), 4923–4944. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP276431

Student Summer Research Projects

Research Models for Investigating Brain Tumors

by Tyler Truex

Reading Hospital Summer Student Intern, Department of Surgery

Preceptors:

Thomas Geng, DO, and Kathleen Lamb, MD

INTRODUCTION FOR BRAIN TUMOR MODELING TYPES

Innovations within brain tumor therapy have progressed slowly throughout the past several decades. Since the 1980s, the median survival period of patients exhibiting glioblastoma (GBM) has only improved by 3.7 months [5]. This lack of improvement is concerning, though it is not surprising, as Glioblastoma, or grade IV astrocytoma, is considered the most aggressive of primary brain tumor types [6]. This resistance to treatment stems from the vast heterogeneity of neoplasms found within the central nervous system (CNS).

Effective models should meet a set of key criteria: (1) replicate the same genetic variabilities, anatomical location, histopathological features, and development time frame as the parent tumor; (2) recapitulate intra- and intertumoral heterogeneity; and (3) reliably predict patients’ response to treatment.

GENETICALLY ENGINEERED MOUSE MODELS (GEMM)

Widely known as one of the most reliable mouse models, the genetically engineered mouse model utilizes knockout genes such as Cre-lox and Tet-inducible expression. Through the analysis of human tumors, tumor-driving mutations (e.g., EGFR, p53, PTEN) are delivered directly into the murine genome. This facilitates de novo tumor formation, mimicking the initial stages of glioblastoma genesis within an immunocompetent, vascularized host. Wide uses of GEMMs are found within the study of glioblastoma formation and to evaluate treatment responses within genetically determined contexts [6,7].

PROS OF THE MODEL

GEMMs replicate human biology and histology, while also maintaining an intact blood-brain barrier and tumor microenvironment. By avoiding injections, GEMMs avoid harming the blood brain barrier while maintaining integrity of the immune system. These models allow for specified manipulation of signaling pathways such as EGFR and PDGFR [6,7]. Notably, GEMMs have been beneficial for evaluating therapies such as

temozolomide (TMZ) and PARP inhibitor ABT-888, helping to clarify mutation-driven drug resistance and outcomes. For example, PTEN-mutant GEMMs exhibited increased sensitivity to merged TMZ and PARP inhibitor ABT-888 therapy compared to p53-mutants; GEMMs also allow evaluation of treatment outcomes in a vascularized, immunocompetent host [11].

CONS OF THE MODEL

GEMMs can form unwanted tumors in non-brain tissues due to the deletion of the tumor suppressor genes (e.g. p53), adding further complications to glioblastoma studies (e.g. CDKn2a-deficient mice develop lymphomas) [9]. GEMMs also require rigorous breeding plans with slow development and high cost [1,10]. Their tumors also frequently display lower genetic heterogeneity than human glioblastoma. Different mouse strain genetics and biological differences (e.g. telomere length) impact tumor characteristics and reduce direct human extrapolation [8]. While GEMMs sufficiently model specified mutations, they do not fully recapitulate the complexity of human tumor genetics.

RECENT FINDINGS

Recent studies using GEMMs have defined the role tumor suppressor pathways (e.g. Rb, Ras) play in glioblastoma development. In one study, inactivating the Rb pathway within mature fibrillary astrocytes via GFAP promoter-driven expression of a shortened SV40 T antigen led to 100% incidence occurrence at 300 days [12]. GEMMs expressing heterozygous PTEN deletion exhibited reduced disease-free dormancy while also developing higher grade tumors with increased cellularity and mitotic activity, marking PTENs role in glioblastoma progression and treatment resistance [12].

PATIENT DERIVED ORGANOIDS

PDOs are multicellular 3D cultures derived from patient tumor samples capable of maintaining the integrity of the original tumor’s physiology and function. They have become effective in vitro model systems to study cancer. Unlike 2D cultures, organoids are able to mimic the natural 3D microenvironment of a tumor.

The quality of an organoid depends on sample origin, culture technique used, and treatment history. Comprehensive glioblastoma PDOs retain driver gene expression and markers, such as Sox-2, Olig2, and EGFR [6]. Exemplary PDOs self-organize+, maintain genomic and phenotypic stability, self-renew, respond to stimuli, mimic tumor heterogeneity, and respond to drug treatments [2].

PROS

PDOs accurately mimic complex cell-to-cell interactions, such as malignancy and dormancy, while also modeling glioblastoma invasiveness; transplanted organoids migrate to brain satellite sites like tumors. Organoids provide promising platforms for personalized treatment development, exhibiting up to 81% sensitivity and 74% specificity in predicting patient response to therapy [2]. For example, PDOs derived from recurrent GBM patients with PTEN mutations and mTOR pathway activation were responsive to mTOR inhibitors, contributing to tumor decline [2]. PDOs also exposed mechanisms such as the role of the neuron-glioma synapse and involvement of NLGN3 in tumor growth; inhibition of NLGN3 suppressed tumor growth within organoid models [6].

CONS

PDOs require specialized labs, restricting availability for many communities. Furthermore, the process is often labor-intensive and time-consuming, requiring resources which many hospitals do not have. Distinct GBM subtypes, prominently IDH-mutant tumors, are harder to replicate than IDH-wildtype [4]. Some organoid procedures necessitate mechanical digestion of tumor tissue to conserve TME and the extracellular matrix. Organoids lack the vasculature and immune components needed for tumor biology and relapse [6]. Issues exist in enhancing subtype-specific culture protocols, expanding accessibility, and reproducing features such as the blood-brain barrier [6].

MODEL TYPE

ADVANTAGES

RECENT FINDINGS

PDOs have been utilized in modeling CAR-T cell therapy responses, exhibiting selective elimination of EGFR-expressing tumor cells and supporting EGFR as a dominant antigen in most patient cases [14]. PDOs also successfully mimicked patient tumor responses in vivo, highlighting their use in therapy outcome testing [13].

HEAD-TO-HEAD COMPARISON

Although each of the models retain key characteristics that make for better uses in different scenarios, several key statistics can be used to compare the two models head-to-head. First is the ability to accurately model patients’ tumor heterogeneity and outcomes of treatment. The PDO exhibits an average of an 84% success rate when modeling the original glioblastoma tumor heterogeneity [3,6]; this is high when compared to the modest average of 55% that the GEMM exhibits [8,10]. This high percentage exhibited by PDOs suggests their promising ability to be used in personalized treatments for glioblastoma drug testing.

Next, when analyzing the predictive accuracy for patient treatment outcomes, PDOs exhibit higher predictive power. As mentioned previously, in 2022, a study was conducted that determined PDOs exhibited 81% sensitivity and 74% specificity when predicting patient responses to therapies to GBM such as TMZ and mTOR [2]. Although GEMMs offer a live, vascularized host, to test therapies, their predictive power is lower at around 4060% depending on factors such as the mutation modeled and the TMZ [10,11,12].

Although these two metrics mentioned are key to glioblastoma modeling, an additional set of seven statistics demonstrate a strong correlation to the ability to accurately model glioblastoma.

DISADVANTAGES

Genetically Engineered Mouse Reliable, Tumor Growth De-Novo, Low-sample Throughput, Expensive, Model (GEMM) Blood-Brain Barrier Intact TME Different from Human [1,8,10]

Patient Derived Organoid

Short timeframe needed to Lack of normal brain tumor microenvironment, (PDO) establish PDOs and test lack of vasculature, and limited personalized therapies residual immune cells [6,16]

CHARACTERISTIC

Tumor Establishment Success

60-90% [3,4,6]

Time to Culture 2-6 weeks

Throughput

Invasion Modeling

Cost per model

High (100s)

90% show invasion

Medium

Ability to model subtypes Hard

Immune System/Vasculature

None

40-70%

3-6 months (Ready for Drug-Testing)

Low (>10)

Low percent of invasion (varying %)

High

Low with genetic alterations

Intact

Student Summer Research Projects

DISCUSSION/FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Both Genetically Engineered Mouse Models (GEMMs) and Patient-Derived Organoids (PDOs) provide key yet unique contributions to glioblastoma modeling. GEMMs provide the opportunity to study tumor formation and immune exchanges in vivo. On the other hand, PDOs provide a better model in preserving patient-specific tumor diversity and drug therapy development. Although overall advantageous, each offer a set of drawbacks as well—GEMMs being expensive and providing less genetic heterogeneity, and PDOs lacking vasculature and immune interactions; each still offers unique ways to tackle glioblastoma treatment. Work done to integrate these two models, such as mice with organoid grafts, should be made a primary focus to treat glioblastoma. By combining these two models, researchers can develop the most optimal glioblastoma treatment.

Tyler Truex is a junior at Eastern University, St. David’s, PA, majoring in biology with the intent to pursue a dual PhD-

4. Xu C, Yuan X, Hou P, Li Z, Wang C, Fang C. Development of glioblastoma organoids and their applications in personalized therapy. Cancer Biol Med. 2023;20(5):353–368. doi:10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2023.0061

5. Walid MS. Prognostic factors for long-term survival after glioblastoma. Perm J. 2008;12(4):45–48. doi:10.7812/TPP/08-027

6. Akter F, Simon B, de Boer NL, Redjal N, Wakimoto H, Shah K. Pre-clinical tumor models of primary brain tumors: Challenges and opportunities. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2021;1875(1):188458. doi:10.1016/j. bbcan.2020.188458

7. Simeonova I, Huillard E. In vivo models of brain tumors: Roles of genetically engineered mouse models in understanding tumor biology and use in preclinical studies. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71(20):4007–4026. doi:10.1007/s00018-0141675-3

8. Huszthy PC, Daphu I, Niclou SP, et al. In vivo models of primary brain tumors: Pitfalls and perspectives. Neuro Oncol. 2012;14(8):979–993. doi:10.1093/neuonc/nos135

9. Huse JT, Holland EC. Genetically engineered mouse models of brain cancer

888 therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(10):2703–2713. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-

12. Hara T, Verma IM. Modeling gliomas using two recombinases. Cancer Res. glioblastoma complexity with organoids for personalized treatments. Trends Mol derived glioblastoma organoids as T cell therapy. Cell Stem

Racial Differences in Dietary Counseling Rates Among Patients with Post-Gastric Surgery Symptoms with History of Bariatric Procedure

by Austin Buskirk, John Fam, MD, Chief, Division of Bariatric Surgery, Thomas Geng, DO, Chief, Department of Surgery, Kathleen Lamb, MD, Vice Chair, Department of Surgery, Xuezhi (Daniel) Jiang, MD, Ph.D, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Reading Hospital/Tower Health

Bariatric surgeries (BS) are procedures that are utilized to help assist patients with complicated obesity to achieve weight loss. The efficacy of these treatments is well documented; however, it is worth noting that a common side effect of bariatric procedures is dumping syndrome (DS), with as many as 10% of bariatric patients experiencing clinically significant DS symptoms. The presentation of DS can vary, but most patients experience gastrointestinal and vasomotor symptoms. While various treatment options exist for DS, the first-line treatment remains dietary counseling. To determine the rates of dietary counseling among DS patients of different races, we retrospectively studied the rates of dietary counseling of patients diagnosed with DS after BS utilizing the TriNetX Network.

We analyzed dietary counseling rates with race as an independent variable by conducting a chi-square test of independence (X 2 = 101.07, v = .109, p value = 3.14 x 10-20) as well as a residual analysis. We found that DS patients in the white racial category were statistically more likely to receive dietary counseling (sr = + 3.10). We also found that DS patients from the Other/Unknown, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and Asian racial categories were statistically less likely to receive dietary counseling (sr = -4.43, -2.02, -2.02. -2.02). DS patients from the Other/Unknown racial categories were least likely to receive dietary counseling. Similarly, when insurance and socioeconomic factors were accounted for, the dietary counseling rates with race as a variable again yielded statistical significance (X 2 = 35.01, v = .166, p value = .00000150).

We conclude that race has an impact on the likelihood that a

Student Summer Research Projects

Stroke Metrics and Functional Outcomes in Predominantly Spanish-Speaking Patients

by Arshia Chhabria, Ty Jozefick, Ricardo Ortiz-Loubriel, MD, Adam Sigal, MD, Traci Deaner, MSN, RN Department of Emergency Medicine, Reading Hospital/Tower Health

INTRODUCTION: Spanish is the second most spoken language in the United States, yet Spanish-speaking patients often face disparities in healthcare delivery and outcomes. Additionally, current data on the impact of limited English proficiency (LEP) on stroke care is often contradictory or contains several limitations. Anderson et al. found no differences in quality benchmarks and outcomes between predominantly English-speaking patients and Spanish-speaking patients (Anderson N., 2020). However, Vargas et al. noted worse neurologic outcome but no difference in functional outcome of Spanish-speaking patients in Texas (Vargas A., 2023). This study focused on investigating the effect of language disparity on quality benchmarks and outcomes in acute ischemic strokes (AIS).

METHODS: All patients with AIS, who were either Spanish or English speaking, presenting to Reading Hospital between January 2017 and December 2022 were included in the study. However, patients with spontaneous hemorrhagic strokes, patients with AIS being transferred to Reading Hospital, patients with a traumatic intracerebral brain hemorrhage, and patients with a prior stroke were excluded from the study. This retrospective study collected data about Demographics, Variable Times, and Outcomes. Comparisons between insurance status, area deprivation index (ADI) score, mean wait times for necessary procedures or scans, and outcomes through a 90-day Modified Rankin Score (MRS) for Spanish-speaking and English-speaking patients were analyzed with chi square, t-test, and logistic regression calculations.

RESULTS: There were 702 English-speaking patients and 119 Spanish-speaking patients in the study. 23% of English-speaking patients recorded a modified ranking scale (MRS) value from 3-6, indicating a poor outcome post hospital. 36% of Spanish-speaking patients recorded an MRS value from 3-6, indicating Spanishspeaking patients were more likely to experience a poor outcome after 90 days from hospital care. The p value was 0.017542, indicating that the data is significant. Spanish-speaking patients were more likely to have private or public insurance. The p value was less than 0.001. The differences can be attributed to a disparity in access to care. A logistic regression was used to control for the confounding variable of insurance to analyze if insurance metrics of Spanish-speaking AIS patients is independent of outcome compared to English-speaking AIS patients. This analysis resulted in a p-value of 0.104 which indicates data that is not statistically

significant. However, Spanish-speakers still had 1.61 times higher odds of poor outcomes. This suggests that insurance may be a confounding factor, though language still shows a trend toward worse outcomes. Additionally, there was a significant delay in the door to CT time (p-value = 0.004). The door to CTA/CTP and door to thrombectomy times were not significant (p-value = 0.14) and (p-value = 0.4). Both national and state ADI scores were significantly higher for Spanish-speaking patients (p-value < 0.0001), indicating a correlation between quality of care and worse socioeconomic disparities.

CONCLUSION: In this study, we conclude that language disparities may result in a lower quality benchmark of care and outcomes for patients presenting with acute ischemic strokes. For benchmarks like CT imaging, geographic socioeconomic factors, and functional outcomes it was clear that there was a variance in care for Spanishspeaking and English-speaking patients. Insurance may be a confounding factor in the MRS score results; however, further data collection is needed to supplement results with greater accuracy and significance. This study can translate into a Language Access Initiative where more awareness is placed on Spanish-speaking patients through stroke education and physician training for treating Spanish-speaking patients during high-acuity events like AIS.

Arshia Chhabria is pursuing a Bachelor’s degree in Biology at Virginia Commonwealth University, with plans to attend medical school after graduating in 2028. She is committed to serving others through medicine and is actively involved in research and community outreach.

Ty Jozefick is currently pursuing a Bachelor’s degree in Biological Sciences at Drexel University, with plans to attend medical school following his graduation in 2028.

References: Anderson N, J. A. (2020). Language disparity is not a significant barrier for time-sensitive care of acute ischemic stroke. BMC Neurology, 20, 363-368. Vargas A, Z. G. (2023). Stroke Outcomes Among English- and Spanish-Speaking Mexican Americans. Neurology. Doi: 10.1212/ WNL.0000000000207275

MESH vs ABCD2: Evaluating the MESH Score as a Clinical Decision-Making Tool for Risk Stratification of Ischemic Stroke after TIA

by William Davis, Peter Aziz, MS, Maxwell Studley, Ryan Gage, Leah Morgan

Preceptors: Tracie S. Deaner, MSN, RN, Adam Sigal, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine, Reading Hospital/Tower Health

INTRODUCTION: Stroke is the 5th leading cause of death and disability in the United States.1 Of the estimated 795,000 strokes occurring annually, 87% are estimated to be caused by an ischemic event, and 10-15% are preceded by a Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA).1,2,3 With nearly half of subsequent strokes occurring within 48 hours, rapid and accurate risk stratification in the emergency department is crucial.4 To meet this clinical need, the ABCD² (age, blood pressure, clinical features, duration of TIA, and presence of diabetes mellitus) score is a widely used tool, though its performance varies, with many studies citing a low specificity.3 A newer MESH score (antiplatelet/anticoagulant history, right bundle branch block, intracranial stenosis >50%, and hypodense area on CT ≥4cm), developed in an Asian population, has shown promising results but requires broader evaluation.

METHODS:

patients diagnosed with a TIA in the Reading Hospital emergency department. Data was collected to calculate the ABCD² score for each patient, and medical records were reviewed to identify subsequent ischemic strokes. The ABCD² score’s performance was evaluated based on its sensitivity, specificity, and the Area Under the receiver operating characteristic Curve (AUC).

RESULTS:

score demonstrated a sensitivity of 83.3% and a specificity of 20.6%. The AUC for the ABCD² score was 0.65, indicating fair discrimination. For comparison, the original MESH validation study reported a lower sensitivity of 71.4% but a dramatically higher specificity of 80.3% and an AUC of 0.81 for the MESH score in their population.

CONCLUSION:

functioned with high sensitivity but poor specificity, limiting its clinical utility. The fair discriminative performance of the ABCD²

score in this initial group underscores the need for a better risk stratification tool. While the MESH score’s lower sensitivity is a cause of concern, its superior specificity may make it a more practical tool for identifying patients who truly require admission and intensive workup. Completing our data collection will allow for a definitive evaluation and comparison of both the ABCD² and MESH scores’ predictive abilities at 2, 7, and 90 days post-TIA.

William Davis, whose hometown is Oley, PA, is a member of the Class of 2028 at Lake Erie College of Osteopathic

Student Summer Research Projects

Menopausal Hormone Therapy and Risk of Eczema in Postmenopausal Women: A Case-Control Study

by Anabelle Vue, Melodi Fugate, Leila Hashemi, DO, Xuezhi Jiang, MD, PhD Dept. of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Reading Hospital/Tower Health

OBJECTIVES: Eczema is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that disproportionately affects women and may be influenced by hormonal changes across the lifespan. Emerging evidence suggests that estrogen may modulate immune responses and skin barrier function, yet the association between Menopausal Hormone Therapy (MHT) and the risk of developing eczema later in life remains unclear. This study was conducted to investigate whether MHT use is associated with a reduced risk of developing eczema in postmenopausal women.

METHODS: We conducted an age-matched case-control study using retrospective data from a single institution between June 1, 2014, and May 31, 2025. A total of 155 women aged 45–70