No. 3

No. 3

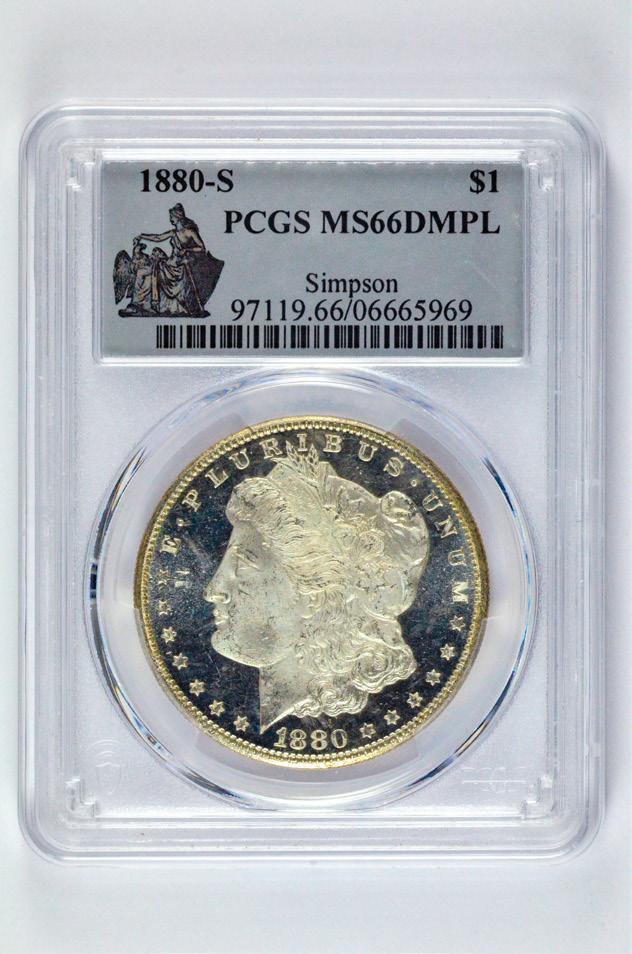

After a 30 year hiatus, Stack’s Bowers Galleries is pleased to present the continued auctions of the James A. Stack, Sr. Collection begun exactly a half century ago. Projected to bring upwards of $20 million, the over 200 coins to be offered have been off the market since at least his passing in 1951. Several individual pieces are valued in excess of $1 million each. Stack, who had begun collecting coins and paper money by the late 1930s, set the goal of building as complete a collection of U.S. coins as time would allow him. In a relatively short time, he built one of the greatest (yet underappreciated) collections of U.S. coins of all time, acquiring many finest known specimens and major rarities, including some that are wholly unknown to current generations of collectors.

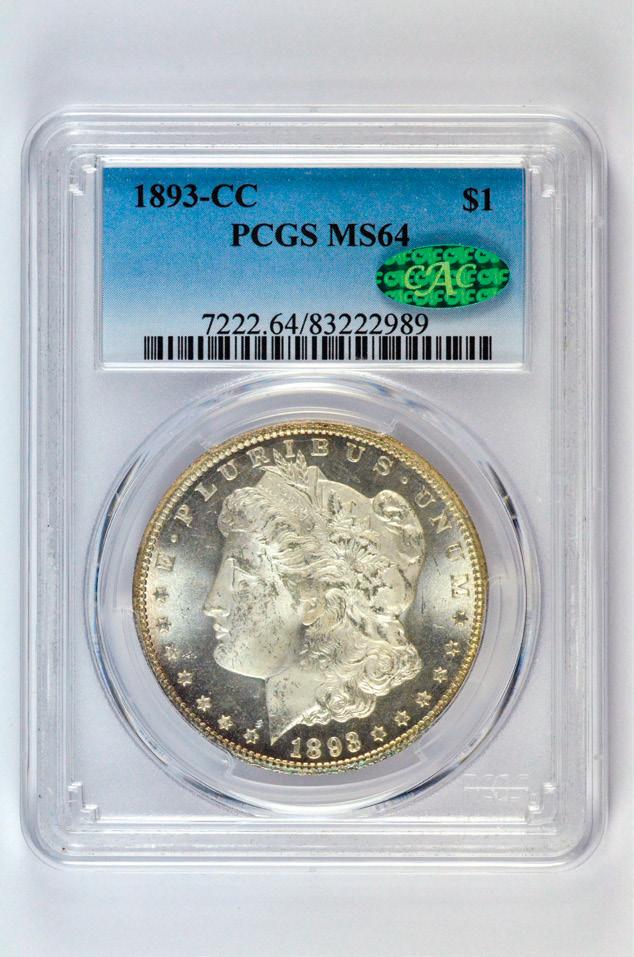

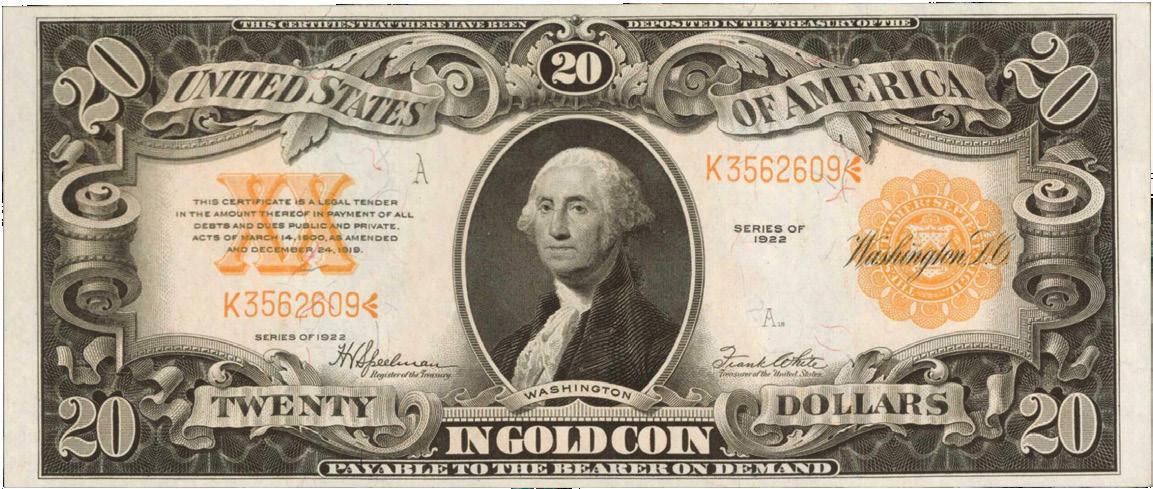

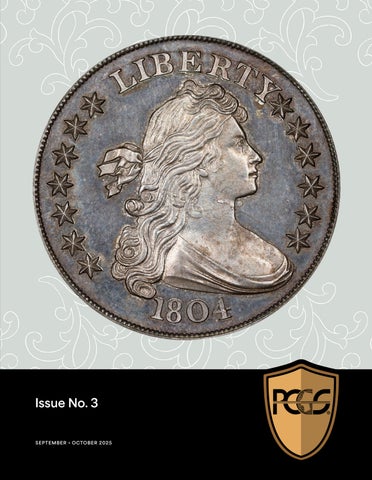

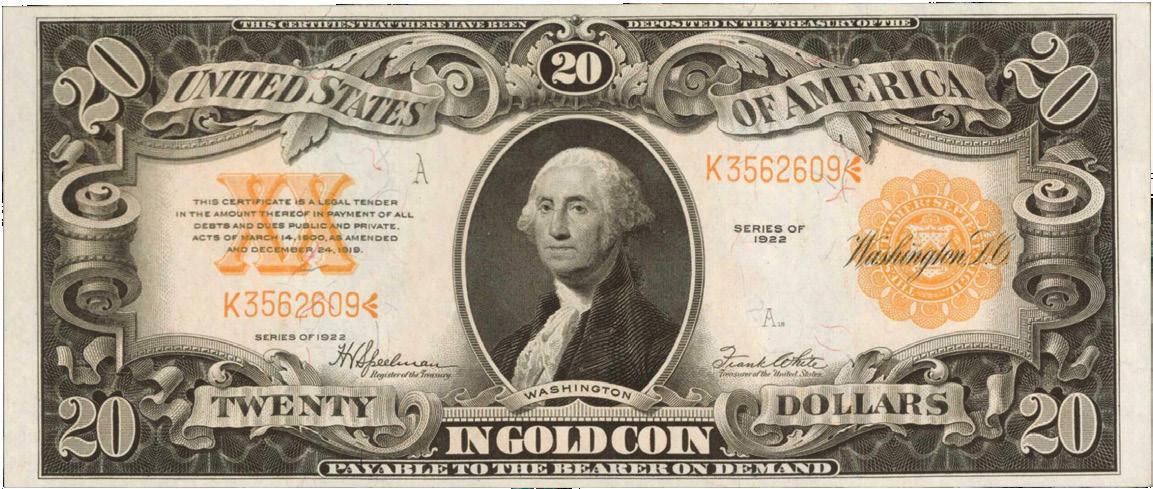

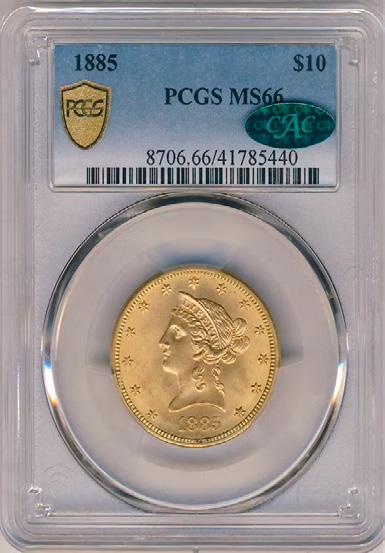

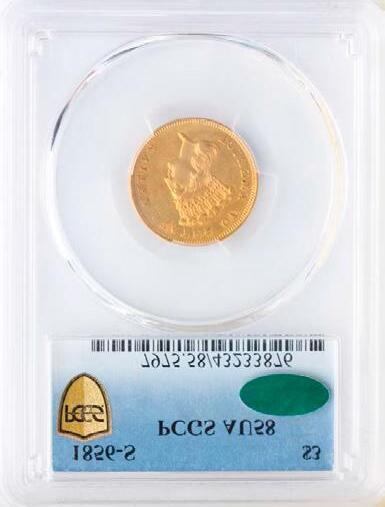

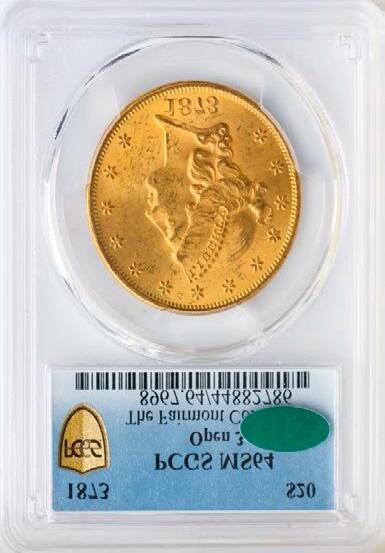

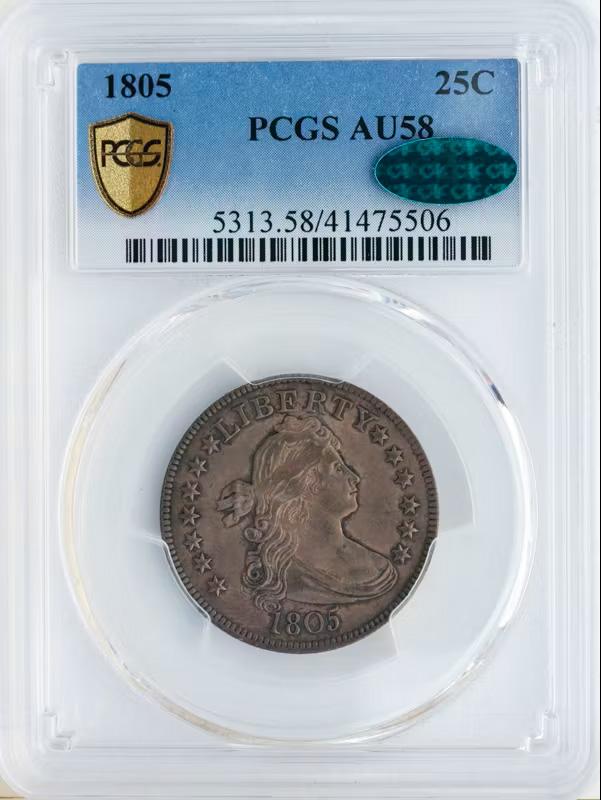

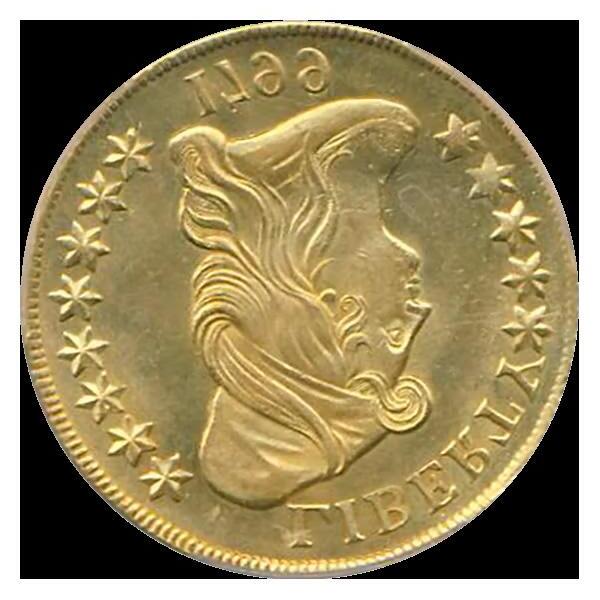

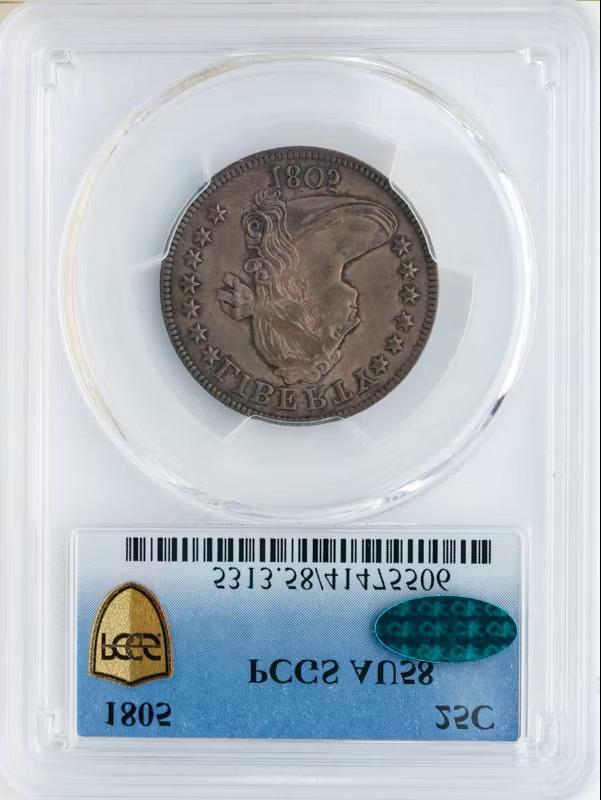

The King of American Coins 1804 Draped Bust Silver Dollar. Class III. PCGS Proof-65 (CAC) (CMQ). A Previously Unpublished Specimen.

The Finest Class III Example in Private Hands.

The Only CAC Verified 1804 Dollar of any Class.

Graded PCGS Proof-61 (CMQ).

The Sole Confirmed Example.

Learn More About the James A. Stack, Sr. Collection at StacksBowers.com

1550 Scenic Ave., Ste. 150, Costa Mesa, CA 92626

949.253.0916 • Info@StacksBowers.com 470 Park Ave., New York, NY 10022

212.582.2580 • NYC@stacksbowers.com Visit Us Online at StacksBowers.com

The Earliest Date of Proof Double Eagle in Private Hands.

Probably from J.C. Morgenthau’s June 1940 Auction.

The numismatic hobby rolls into autumn with heat, and we’re not necessarily talking about summertime temperatures or muggy dew points. The heat is searing on coin show bourse floors and around numismatic auction lecterns. PCGS will be accepting submissions at the International Money Exposition being held in Nashville, Tennessee, September 4-6, and serves as the official on-site grading service of the Great American Coin and Collectibles Show, in Rosemont, Illinois, September 25-27. Then, PCGS has its inaugural Trade & Grade event in Irvine, California, October 22-25.

But that’s not all. We’re excited to announce that PCGS has launched grading for certain ancient Chinese coins, which will be graded on a new grading scale that promises to become the new industry standard. You will learn all about this new PCGS ancient coin grading service and its unparalleled suite of guarantees and benefits among the pages of this PCGS Insider

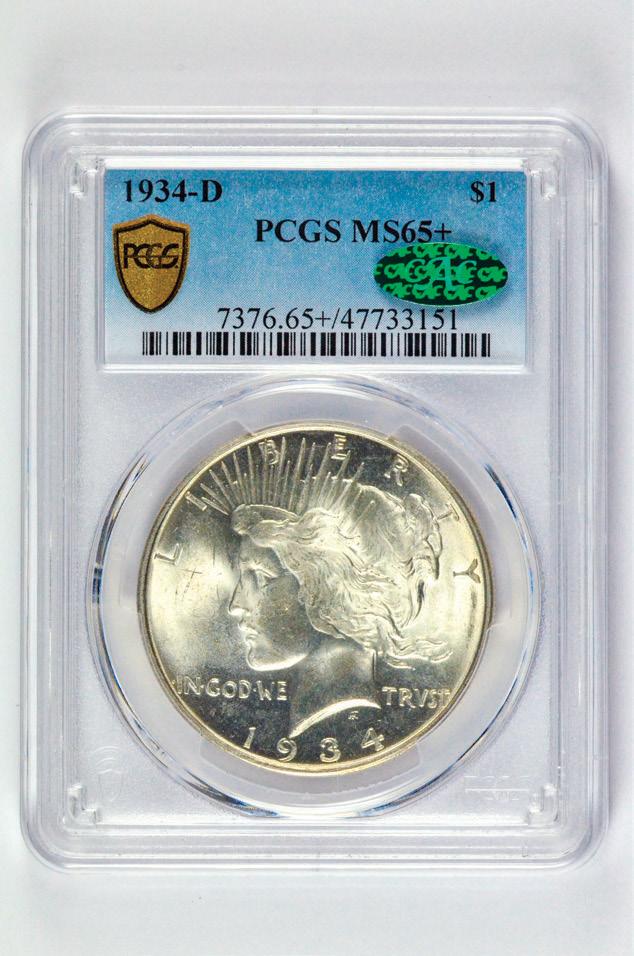

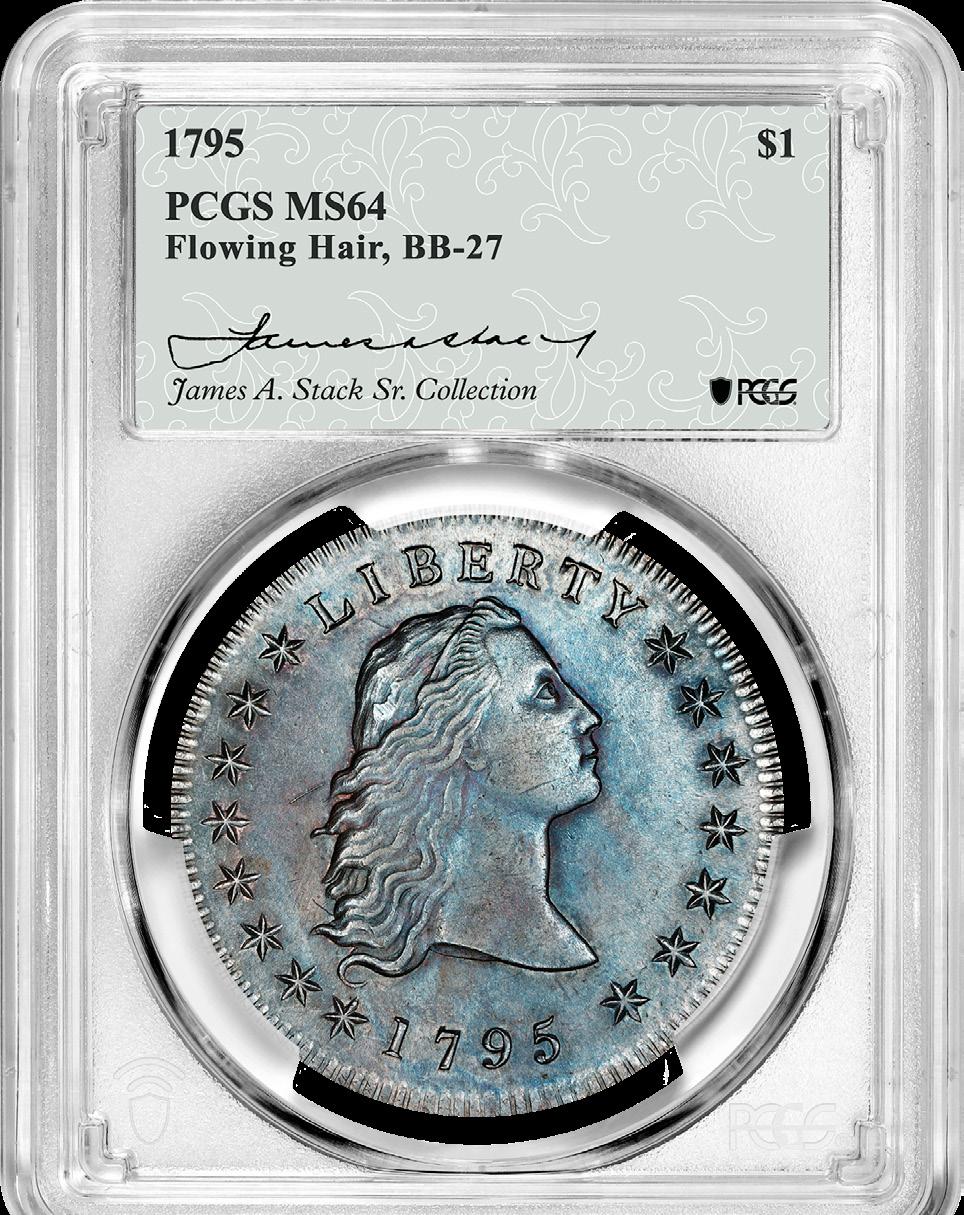

Another exciting thing we feature with this issue is our unprecedented variant cover. That’s right! The cover on this issue of PCGS Insider is one of three that grace the September-October edition of our flagship magazine. Each of these three covers showcases one of the many magnificent offerings from the James A. Stack, Sr., Collection, a historic cabinet that is being sold by Stack’s Bowers Galleries. Highlights from this prestigious collection are detailed in the PCGS Featured Coins (plural!) article on Page 6.

The innovative and artistic variant covers we unveil with this issue are certain to become coveted collectibles themselves and represent just one of the many ways we’re elevating the quality of our new magazine. Now entering its third edition, PCGS Insider offers an unrivaled variety of exclusive analysis, in-depth numismatic insight, and a wealth of other resources from the experts you trust.

We hope you enjoy this third edition of PCGS Insider in good numismatic health!

Happy Collecting,

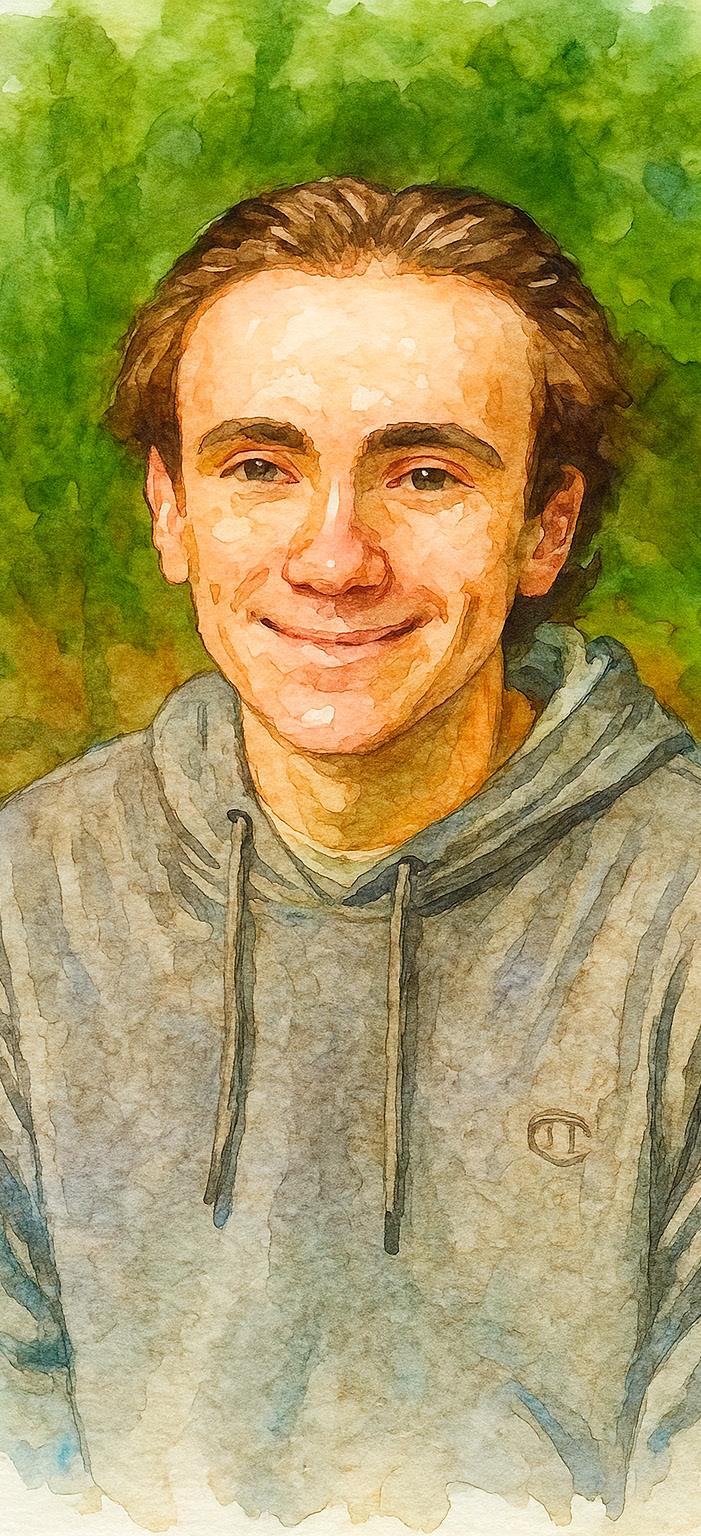

Joshua McMorrow-Hernandez PCGS Insider Editor-in-Chief

Editor-in-Chief

JOSHUA MCMORROW-HERNANDEZ

Creative Director

JACK ARCHER

Art Director

GEOFF PARRISH

KEITH DEWALD

Designer JAMES DAVIS

Production Artist CHRIS WILSON

Staff Writer

SANJAY C. GANDHI

ABIGAIL ZECHMAN

EDWARD VAN ORDEN

JAY TURNER

JAIME HERNANDEZ

VIC BOZARTH

PHILIP THOMAS

Contributing Writer

PETER ANTHONY CHRISTOPHER BULFINCH

Advertising TARYN WARRECKER ARIANNA TORTOMASI

PCGS INSIDER

PCGS Insider Magazine USPS Pending Periodical #226, Copyright © 2025 by The Collectors Universe is published bimonthly by The Collectors Universe, 1610 E St Andrew Pl, Santa Ana, California, 92705. Application to Mail at Periodicals postage is Pending at Santa Ana, CA and additional mailing offices. Printed in Canada.

Nothing herein is intended to provide financial advice. Past sales do not guarantee future results.

Send address changes to Collectors Universe, 1610 E St Andrew Pl, Santa Ana. California, 92705.

BUSINESS & EDITORIAL OFFICES 1610 E St Andrew Pl Santa Ana, CA 92705 (949) 567-1234

ACCOUNTING & CIRCULATION OFFICES 1610 E St Andrew Pl Santa Ana, CA 92705 (949) 567-1234

Call (949) 567-1234 to subscribe. Periodical postage is paid at Blaine, WA.

By Joshua McMorrow-Hernandez

Every once in a great while, the numismatic world is treated to the sale of a landmark coin collection – one featuring magnificent seven-figure rarities with the gravitas to command headlines in the general media and across the hobby. The appearance of the James A. Stack, Sr., Collection is one such occasion. Stack’s Bowers Galleries is proud to present this cabinet of over 200 resplendent coins, boasting rarities that have been off the market since at least the time of Stack’s passing in 1951.

Stack was unrelated to but shared a last name with his friends Joseph B. and Morton Stack, who were founders of Stack’s Rare Coins. However, the impassioned collector built a numismatic legacy that became intertwined with the preeminent coin firm. James A. Stack stipulated that his coin collection was to be divided among his three children. He further instructed that the collection must remain intact and later be passed down to his grandchildren after the youngest (at the time of Stack’s passing) turned 25 years old.

Eventually, the first coins from the collection emerged for the Stack’s March 1975 auction, with later major offerings in 1989, 1990, 1994, and 1995, among other auctions. These sales provided a glimpse into just how complete Stack’s collection was, suggesting that had the collection been sold in a single offering it might have gone down as the greatest numismatic auction of the 20th century.

As the numismatic fates dictated, Stack’s Bowers Galleries continues a numismatic tradition that began half a century ago in 1975 with the next chapter for the storied James A. Stack, Sr., Collection. Crossing the block are coins valued at a cumulative $20 million and that entail several rarities individually worth more than $1 million.

Among the sensational trophies included in this sale, to be held across two offerings in December 2025 and February 2026, is a previously unpublished example of the legendary 1804 Class III Draped Bust Dollar (PCGS Proof-65) known as “The King of American Coins.” Other spectacular offerings are the 1795 Three Leaves Flowing Hair Dollar (PCGS MS64) and 1859 Liberty Head Double Eagle (PCGS PR64DCAM).

In keeping with the quality and rarity of the James A. Stack, Sr., Collection coins auctioned in the 1970s through 1990s, this selection of coins includes a multitude of finest-known specimens as well as many pieces that have never before been documented. There are also some returning favorites, such as a PCGS AU53 1798 Small Eagle Half Eagle that last sold in a 1946 B. Max Mehl auction. Rounding out the collection are more than two dozen Territorial gold pieces with provenances dating back more than a century.

“The James A. Stack, Sr., name has long been well regarded at Stack’s and among those in the hobby who were around for the original auctions decades ago,”

commented Vicken Yegparian, executive vice president at Stack’s Bowers Galleries. “I’m ecstatic that current generations will get a taste of the greatness of the James A. Stack, Sr. Collection. As if an 1804 Class III silver dollar that had evaded detection by several generations of the best researchers was not enough, there is also a stellar array of expectation-busting coins behind it. This tranche of coins from the Stack Collection shows that there are still ground-breaking discoveries to be made in numismatics.”

Further details of this historic sale will be shared with the public in the coming weeks. For more information, please visit www.stacksbowers.com and follow Stack’s Bowers Galleries social media and e-blasts.

By Sanjay C. Gandhi

The city of Troyes, France, may not be as familiar as the French megalopolis known as Paris. However, the British traded with the French merchants in Troyes starting in the 9th century. This was the city where the term “troy” was derived that’s commonly used today as a measure for gold and silver. Fast forward 700 years to 1527, and Great Britain developed the troy pound as a standard monetary weight for both silver and gold. A troy pound of silver is equal to 12 troy ounces of silver. Each troy ounce is equivalent to 480 grains, and a grain is an ancient unit of measure equivalent to a kernel of barley.

Around the same time period, there also was a troy ounce in Bremen, Germany, that was equal to 480.1 grains. Nowadays, we are more familiar with a troy ounce being measured in grams and equivalent to 31.1 grams. The first bolt-and-screw press used to manufacture coins was invented by the British in 1661. This technology was refined in the ensuing years. By 1732, Mexico received its first screw press, which they called “de balacin” and began minting coins for the Spanish Empire. Mexico has historically been rich with silver ore, and they are the largest global producer of silver today.

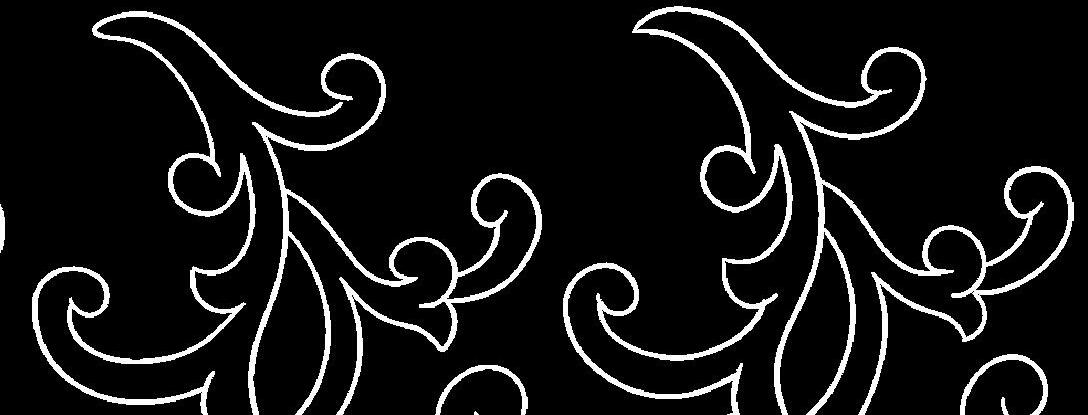

In 1936, the Banco de México produced a medal commemorating 400 years of coinage, as shown above. The obverse of the medal was designed by Manuel Luna Negrete, whose initials can be seen at the bottom left of the bolt-andscrew press, which is the central design. The reverse shows a modern steam press that was used at the time.

Mexico had first conceived the idea of minting a bullion coin in 1947, and the first “Onza Troy” (or one-ounce silver coin) was coined as a pattern. Struck in a proof finish, this coin uses the same design as the Negrete medallic issue from 1936. Collectors in Mexico distinguish between the “Onza Troy” minted from 1949 through 1980 and “Onza Libertad,” which was struck from 1982 through the present.

In 1949, the Banco de México issued a silver one-ounce coin struck in a circulation finish, and it was the first silver bullion coin issued by a government. This 1947 pattern issue was the predecessor for the 1949 Onza Troy bullion issue, which has the same design. The total mintage was 1,000,000 coins. This issue also displays the bolt-and-screw press with the remainder of the obverse displaying the date 1949. The legend reads “CASA DE MONEDA DE MEXICO.”

Our reverse displays “LEY .925,” which is the purity of the silver, “480 GRANOS OF PLATA,” and this translates to 480 grains – equivalent to one troy ounce. These coins were bullion that was traded between banks and were equivalent to about one U.S. dollar per coin. A PCGS MS65 1949 Mexico Onza would cost a collector about $250 nowadays.

The 1949 onza coins were traded similarly to how United States Morgan dollars were being traded in bags with the exception that the Mexican Onza Troy is one ounce of pure silver. Once the price of silver began to rise in the 1960s, silver was less frequently used in coinage, and withdrawing silver from circulation became a worldwide trend. The use of non-precious materials such as copper-nickel became more widespread for coining.

Silver reached about $2.50 per ounce in 1968, and then it hit $1.30 in 1971. Soon, the 1970s energy crisis pushed silver along for the ride to about $3.00 per ounce by 1973. This was the same year that two brothers in Texas, named Nelson Bunker Hunt and William Herbert Hunt, bought 35 million ounces of silver. The brothers began to dabble in the silver market on the Commodity Exchange (COMEX) as well as in the form of “futures”; futures are a contractual agreement to buy a commodity at a future date and at a set price.

For example, one may purchase a contract, which represents 5,000 ounces of silver for the date September 21, 2025, for a fixed currency amount. One may exercise the contract and take physical delivery of the silver or outright sell the contract at a profit or a loss. In 1974, the Hunt Brothers inherited a large fortune worth billions from their father, who was in the oil business. They began to dabble in futures contracts and continued to accumulate millions and millions of ounces of silver over the next several years.

In 1978, the Banco de México saw an increase in demand for silver bullion and issued its first onza coin in over 29 years. The design was similar to the 1949 issue, but the reverse now displayed a balance and scale on the back. Two varieties exist for the 1978 issue: Type 1 has wide spacing between “DE MONEDA,” and Type 2 has close spacing between “DE MONEDA.” Both of these varieties command about $250 in a PCGS Mint State grade.

The 1978 date had a mintage of 280,000 coins. The 1979 coin also has two varieties that exist. On the Type 3 1979 there is close spacing between “DE MONEDA,” the left scale points to the U in “UNA.” Type 4 1979, there is close spacing between “DE MONEDA,” the left scale points between the U in “UNA.” Both of these varieties sell for about $120 each in a PCGS MS65 grade.

At the beginning of 1979, the price of silver stood at about $6 per troy ounce. The mintage for these coins was 4,508,000 and Banco de México sold them between $5.94 and $32.20 per coin. Prices would continue to rise into the next year as well. By this time, the Hunt Brothers had accumulated a massive position in physical silver and futures contracts. Their belief had been that silver would rise due to inflationary pressures.

The Banco de México issued Onza Troy coins in 1980, yielding three date-based varieties: 1980, 1980/9, and 1980/79. The scarcest is the 1980/9 variety, and the other two are of

about equal scarcity. In the PCGS MS65 grade, all three of these varieties will trade between $100 and $150. The Banco de México produced 6,104,000 of the Onza Troy coins in 1980, selling them for between $10.89 and $49.25 per coin, plus a premium for coining.

The year 1980 was when the Hunt Brothers had cornered the silver market. With several years of accumulating physical silver and futures contracts, the Hunts controlled about one-third of the global supply of silver that was not held by government institutions. On January 7, 1980, the COMEX introduced the “Silver 7 Rule,” which placed heavy restrictions on buying silver commodities on margin.

The COMEX also feared that if the price of silver fell, people who had borrowed funds to speculate on the price of silver, which is called margin, would not be able to meet their financial obligations. Margin accounts are used to borrow money from financial institutions/brokers to buy futures contracts or even stocks. For example, if an investor wants to buy 5,000 troy ounces of silver, they may borrow half of the money from their broker as a loan, and pay half the money upfront, which is called the cash requirement. In this case, the cash requirement is 50% and you essentially double your buying power as long as the commodity does not fall below 50% in value. If the value does fall below 50%, the investor would receive a margin call, meaning the speculator would need to add cash to the account to maintain a 50% cash position.

The speculation in silver continued to be rampant. On January 18, 1980, silver futures traded at a record high of $50.53 per troy ounce! Government regulators and COMEX officials knew of the heavy accumulation of silver contracts by the two brothers from Texas, and they were not the only speculators betting on silver. There was strong evidence that the Hunt Brothers were manipulating the price of silver.

On March 27, 1980, which was known as “Silver Thursday,” the Hunt Brothers received a margin call of $100 million. They were unable to meet the financial requirements, and the price of silver fell from $21.62 per ounce to $10.80. Years of speculating endeavors forced the Hunt Brothers to file for bankruptcy. Their losses amounted to billions. Over the next decade, they had to testify before Congress, arrange for financing to meet their financial obligations, and pay all of their creditors. Even though the Hunt Brothers lost billions, they remained wealthy.

The “Onza Troy” series has four dates: 1949, 1978, 1979, and 1980. However, completing the following PCGS Registry Set known as Mexican Onza Troy Silver with Varieties, Circulation Strikes (1949-1980) will be challenging for members to complete. This is especially so for a set in a PCGS MS66 grade, since the fields on both sides of these coins are open and more prone to dings. Colorful or toned examples of these coins will sell for premiums depending on the color scheme and attractiveness.

Collectors may notice the mintages are fairly high for all the years. By analyzing the PCGS Population Report, this series compared to others seems quite low and affordable, which may become more noticed by collectors of Mexico. In 1981, the Banco de México did not strike a Troy Onza, possibly because the premiums they once collected per ounce of silver had disappeared. Keep in mind also that the price of silver had dropped during the entire year of 1981 and finished at a year low in December. However, in 1982, a newly designed one-ounce bullion coin was released by Banco de México: the Onza Libertad.

By Vic Bozarth

I’ve been a collector for more than 50 years and was a full-time dealer for 35 years before I came to PCGS. In that time, I’ve learned there’s a big difference between talking about coins and collecting – or indeed actively buying and selling –coins. Regardless of your numismatic interest level, at some point, your involvement with coins requires action.

I often share a variation of the following statement I first heard around 1974 or 1975: “If you haven’t lost money on a rare coin, you are not buying enough coins.” Hmm, really? How’s that work?

Their point, and I have found this to be nearly absolute, is if you want to play (at anything) you have to lose to learn. Now, nobody ever wants to lose, but sometimes losing comes part and parcel with almost anything. Buying and selling real estate. Playing sports. You get the idea. Losing sometimes is part of the risk/reward dynamic.

And, before PCGS entered the numismatic world in 1986, that risk factor surely seemed a lot riskier. “BP” – Before

PCGS, that is – the coin market was plagued with hype surrounding purported “rare, investment-grade coins,” such as Morgan Dollars, at increasing prices that promised “GEM BU” quality, a grading adjective that roughly equates to MS65. Much of this largely over-graded material would eventually end up with someone who didn’t know any better.

Was the dealer grading the coin(s) correctly? Did the customer know the difference in grading or how much difference this “grade” would make later at the point of sale? Here’s the rub: so many customers bought “great deals” like this, some believing for decades they had “rare” coins, only to find out that, at the point of sale, they had been at the very least oversold.

Regardless of your motives, don’t you want to know you are getting what you paid for?

PCGS was founded in 1986 because of how rampant such scenarios were. When the company first began authenticating and grading coins, I realized that

when buying PCGS-graded coins the underlying question about “quality” was no longer a concern. I didn’t have any discretionary money, but in early 1987 I scraped up about $300 and bought a Mercury Dime graded MS65FB, a Buffalo Nickel in MS66, and a Liberty Nickel in MS64 – all PCGS graded.

I took the plunge on buying those three coins (when I could barely afford to do so) and learned that PCGS changed everything! I used those three PCGSgraded coins, as well as additional PCGS coins I later purchased for myself or held as a dealer, as my templates for what to look for among the raw coins available for sale. In other words, PCGS helped me learn to grade to the standards they required, thus enabling me to gain confidence in my grading abilities. I also discovered first-hand just how consistent and “tight” PCGS grading standards are. And that’s why PCGS coins can bring more money. Do you want to see what I mean by this? Take the plunge and find out for yourself!

By Peter Anthony

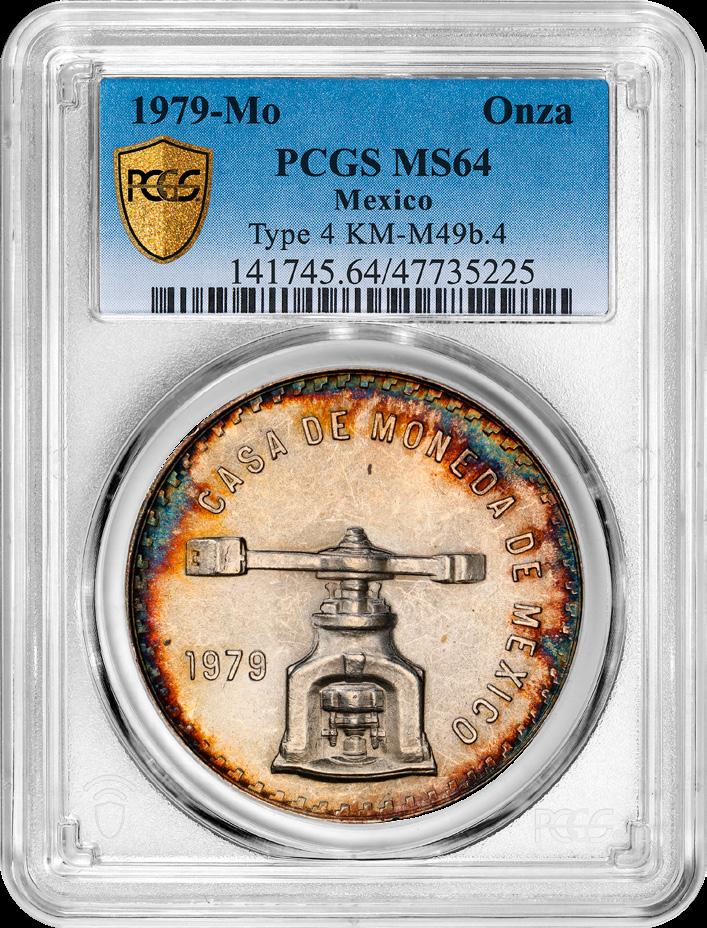

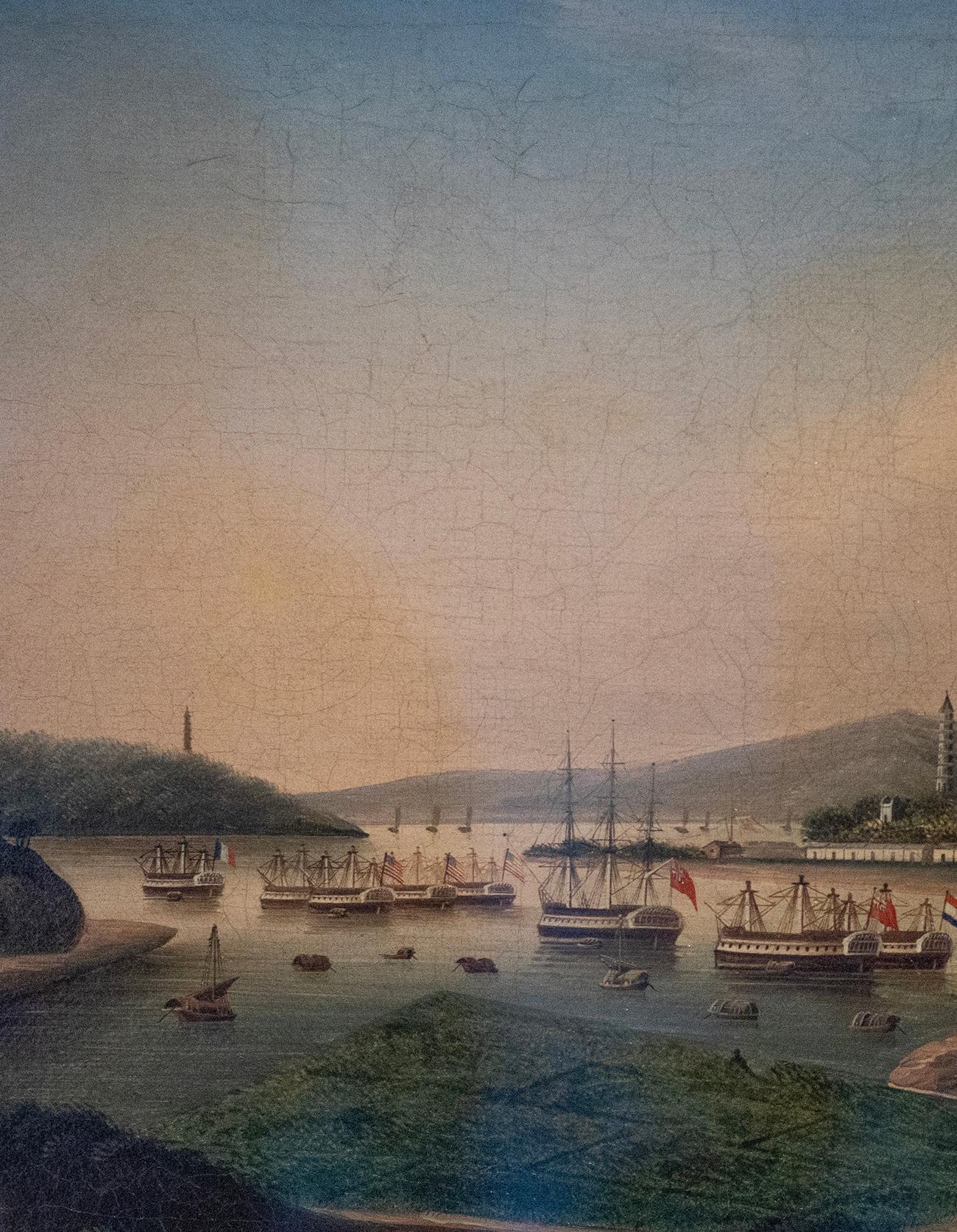

“Canton ahead!” The wooden ship’s deck shuddered. The British crew on the Bombay had been at sea for more than a year. In those months, sailors had been blown overboard in storms and lost to illness. Scurvy had broken out. A mast had snapped in a gale south of the Cape of Good Hope. That cost the East India Company vessel a couple of months to fix. Now that their destination was finally in sight, everyone was topside as a pagoda rose into view.

The merchant ship inched forward as it fought the current. Entry into the Pearl River Delta was through a strait called Bocca Tigris — the Tiger’s mouth. A Chinese gun emplacement cast a wary eye on the foreign devils, and a pair of Chinese boats rowed out to escort the vessel.

The Bombay joined a row of competing ships docked at Whampoa Roads outside the city. Western vessels were not permitted upriver, and the crew was confined to a narrow factory district outside the city walls called the thirteen hongs. In 1757, the Qing government ordered all ports except Canton, to be closed to foreign traders, especially the English.

This was triggered by British attempts to encroach on the emperor’s territory through Tibet and Nepal, along with unsanctioned visits to other cities.

By imperial decree, contact with Chinese nationals was severely limited. Indeed, it was forbidden for the two groups to even learn each other’s language. Despite this, by the mid1700s Chinese merchants figured out how to communicate with their customers through a phonetic form of common English phrases.

The streets near the factories were lined with shops filled with highly desirable export goods. Silks, enameled housewares, and exquisite lacquerware were just some of the items for sale. As one visitor wrote, “There is such a peculiarity, such a neatness and ingenuity about everything made by the Chinese, that a European feels in the situation of a child, taken, for the first time in his life, into a large toy-shop.”

For extra ballast on the voyage home, the first teapots to Europe, formed from heavy red clay in the town of Yi Xing, were stacked in the lowest hold. Every inch on the ship was worth money. A smart sailor could use his pay to load up on Chinese goods and double or triple his bankroll back home. After a few voyages, he might join the middle class in England.

In any case, the foreigners were here to buy. Some £30,000 in Spanish silver coins were sealed with tar in the hold of the Bombay. These first saw light as ore from the prolific silver mines of South America that was smelted and then minted into coins in Lima, Peru. The obverses depict the crowned arms of Peru, while the reverses feature a globe topped by a crown flanked by two pillars. Each 8 reales coin contained around 27 grams of .910-fine silver.

A 1986 5 Yuan silver coin has very similar specifications to the Spanish 8 Reales and illustrates what the Bombay might have looked like. The Empress of China 5 Yuan commemorative coin contains 26.7 grams of .900-fine silver and is 36 millimeters in diameter. In 1728 and again in 1750, the Spanish government decreed that the gold-to-silver ratio was 16:1. Everywhere else in the world, it was closer to 15:1. This made silver in Spain undervalued relative to gold and led to a flood of foreign gold imports and silver coin exports. By virtue of quantity and quality, Spanish silver became the world’s standard trade coins. Annual mintages in Lima alone could reach into the millions of coins.

In Canton, the Chinese merchants tested these coins and stamped them with chop marks as verification. While copper alloy cash coins were the legal tender of China, silver was demanded for tax payments. Also, the silver was needed by the British to pay a tax on tea exports to the emperor in Beijing.

So, what did the British captain plan to buy with the silver coins in his ship? All the tea he could carry! Eventually, if the journey went well, whatever the Bombay delivered would be sold at the East India Company’s tea auctions in London. There, the company could triple its investment on the voyage.

Throughout Britain and its colonies there was a mania for tea, one that the company was eager to promote. The first tea arrived in London in the 1650s. Its taste, so different from common English drinks, became a sensation. Initially, it was also rare and expensive and therefore fashionable. The first teas imported were a cheap variety of black tea – called Bohea after the hills where it grew – but no one in Britain knew that, yet.

More supply was needed to meet the insatiable demand. Due to excellent growing conditions, the mountainsides of Fukien Province in China were planted with tea trees. It took time, but by the 1720s, the supply of Bohea tea overflowed and its price fell. The brew became affordable for ordinary folk and lost its caché. The chi-chi crowd moved on to more novel and delicate tea varieties. Regardless, the overall demand for tea in England and its colonies quadrupled from 1720 to 1740 and doubled again in the eight years from 1763 to 1771.

All of this meant staggering profits for the main importer, the East India Company. Controlled by a small group of families, it also ran the distribution and even ownership of the choice of crews and the ships. Extreme wealth flowed into England, but it went to a highly concentrated group of people. East India Company profits from tea trading in 1771 were £300,000, the equivalent of $900 million today. For comparison, at this time, a skilled craftsman in London might earn around 1/10£, or $300 in today’s money, in a week.

Meanwhile, the British Empire had gotten into conflicts such as the Seven Years War and the French and Indian War. These saddled the government with a serious debt load. In response, the crown imposed new taxes, both at home and on its colonies. Taxes were raised as high as 119% on tea leaves, which led to widespread smuggling. London also imposed a suite of taxes on its colonies. Particularly irksome was a threepenny tax on a pound of tea imposed in 1767, but there were others like a tax on molasses, a key ingredient of rum. Most tax payments, along with the majority of other business in the colonies, were paid for with the same kind of coinage preferred in China: Spanish silver.

The colony of Rhode Island was a center for maritime trade. Among the colonies, its charter was particularly expansive. Every public office was to be filled through an election. It was also a hotbed for independent thinking. The freest of those contrived that since Rhode Island’s charter required that all laws be approved by a representative assembly, and as the colony had no representation in British Parliament, the mother country’s laws – and especially its taxes – were invalid. In other words, the Crown had no legal right to collect taxes from Rhode Island.

This conflict broke out into the open when the Royal Navy sent a schooner, the Gaspée, to patrol the colony’s seacoast. Its mission: seize any ships that carried untaxed cargo. Tax laws, however, were so complicated and obtuse that even the best-intentioned boat might violate them. Then again, not all of Rhode Island’s shippers had any intention to pay the tolls. This was a target-rich environment for the enforcers.

The Gaspée was commanded by an aggressive young Scotsman. This son of a noble but indebted family was widely known for his foul mouth and eagerness to settle disputes with his fists. Lieutenant William Dudingston’s pay was low, but he could receive a share of the auction proceeds whenever he caught a smuggler’s ship, or any ship, for that matter. Considered little more than a legalized pirate by the colonists, his zeal to collect bounties made him a marked man around Newport and Providence — but, by the time he retired from the navy decades later, he could afford two expensive English homes.

On June 10, 1773, the Gaspée spotted a sloop near shore called the Hannah and gave chase. The skipper aboard Hannah knew these waters well. Dudingston did not. By a deft maneuver the Hannah escaped and left the Gaspée grounded. Late that night, a small flotilla of whaling boats filled with angry Rhode Island folk dressed up as indigenous peoples approached the stranded ship. Aroused too late, the sailors had barely time to fire off a few shots. A cursing Dudingston drew his cutlass and was about to strike a boarder when two musket blasts felled him. The Gaspée was forcibly abandoned, the sailors later released, and Dudingston’s rather serious wounds tended to by a doctor among the raiders. The Gaspée was burned to its waterline.

The incident was a virtual dress rehearsal for what followed six months later. By 1773, the supply of tea from China had caught up with demand in England. Prices, profits, and tax receipts were down. The government in London responded with a plan to dump the excess tea on the colonies. The East India Company was given an effective legal monopoly on tea imports to the colonies — which were still obliged to pay the threepenny tea tax.

On the night of December 16, 1773, the East India Company ship Dartmouth lay moored in Boston Harbor, its hold filled with Chinese tea. Dressed as indigenous Americans, a group of colonists seized control of the ship and threw 342 chests, more than 92,000 pounds of tea, into the harbor.

The Boston Tea Party is famous as a prelude to the revolution that followed. Not much thought is usually given to the long trail of commerce that led up to that event, but it involved not one, but three empires. Tea that was grown and harvested in the mountains of China was sold in the port of Canton for silver coins minted by Spain. It then passed through England. From there, its journey ended not in a kettle and a teacup, but by making a splash in the waters of Boston Bay and the pages of history.

What a trip!

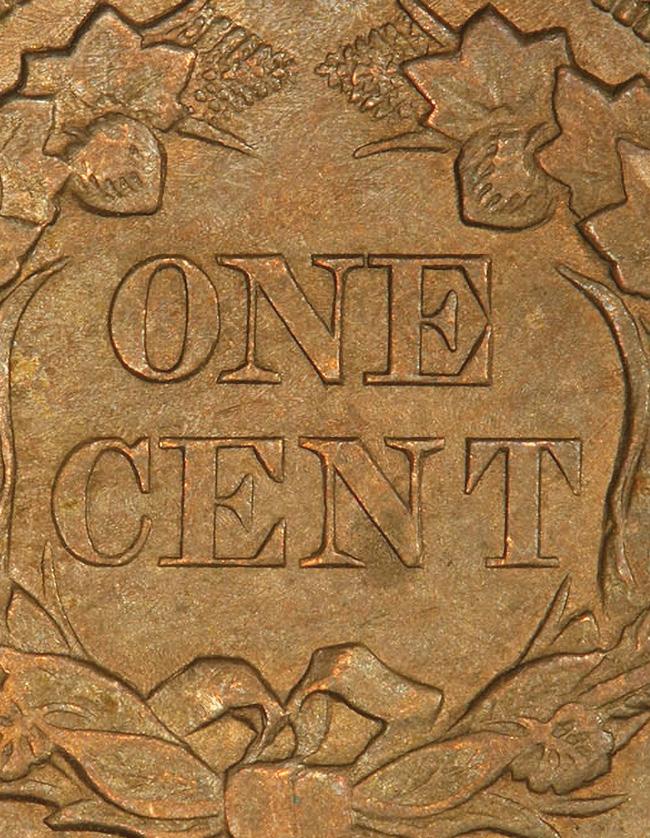

By Joshua McMorrow-Hernandez

The United States government has formally discussed plans for eliminating the one cent coin since at least the 1980s. However, it appears the denomination is heading for its final curtain call as the year 2025 winds down. Earlier this year, government officials decided the one cent coin, which costs about 3.9 cents per coin to produce, should be eliminated. In May, the United States Treasury placed its final order of planchets to strike the coin. How long this planchet supply is expected to last is uncertain, but short of an 11th-hour change of plans, it looks like the last one-cent coins will soon be rolling off United States Mint presses. And with that would come the end of a numismatic tradition that began in 1793, when the first one cent coins were officially struck by the United States Mint for widespread circulation.

It marks the end of an era and the beginning of a new one: the time when the United States one cent denomination is technically obsolete. We may still see “pennies” in circulation for many years to come. After all, more than 100 billion are estimated to still be milling about in channels of commerce. Yet, with the end of the one cent coin drawing near, numismatists call to mind the incredible catalog of coins that the cent has produced over the years. We’re talking about many hundreds of issues and thousands of attributable varieties for countless numismatists to enjoy and collect.

Let’s look at 10 of the most important one cent coins to come along over the last 232 years, beginning with the first.

The United States government experimented with a variety of pattern coins in the 1780s and early 1790s before the enactment of the Coinage Act of 1792, which established the United States Mint and mapped out the nation’s official coin system, including the one cent coin. It was indeed the one cent piece that became the first U.S. coin officially struck at scale and distributed into circulation for widespread use in commerce. The first iteration of the denomination was the Chain Cent, struck in February and March 1793. The original Chain Cent, bearing an obverse portrait of Miss Liberty with flowing hair, shows the inscription “UNITED STATES AMERI.”

The stated mintage for the 1793 Chain AMERI Cent is 36,103, but that is inclusive of two types of variations that show a complete version of “AMERICA.” Most importantly, PCGS estimates only 187 specimens of the 1793 Chain AMERI exist in any grade, with just two in uncirculated grades and only one at the MS65-or-better tier. What’s clear is that these coins aren’t just rare – they’re American treasures. And an example grading G4 is easily a $10,000 coin.

A case could be made that the 1799 Draped Bust Cent was among the first great rarities recognized by American numismatists. In the mid-19th century, when coin collecting was really beginning to take off in the United States, the large cent was a prime area of focus for the nation’s numismatic scholars. And it was realized early on that two dates were seemingly impossible to find: the 1799 and the 1815.

As collectors came to discover, there are no 1815-dated United States one cent coins. As for the 1799 cent, they exist but are extremely rare. An original mintage of just 42,540 has yielded fewer than 1,000 survivors. There were two variants of that date, and both are extremely rare. There is the 1799 and the 1799/8 overdate. PCGS estimates there are 700 examples of the 1799 across all grades and just 200 of the 1799/8 variety. Only one Mint State example exists across these two variants – a 1799 graded PCGS MS61BN with an estimated value approaching $1 million. The circulated examples of either 1799 variant start at around $5,000.

Rising costs of production and inflation led to the demise of the large cent in 1857. But the denomination continued on in the form of the small cent. The coin was the culmination of many efforts to make the one-cent coin less costly for the U.S. government to produce and more palatable for the American public to carry in larger quantities, especially as the cost of living increased over the course of the mid-19th century. Chief Engraver of the United States Mint James B. Longacre designed the Flying Eagle Cent, which was struck in limited quantities in 1856.

The 1856 Flying Eagle Cent was produced for exhibition before congresspeople and other civic stakeholders. However, while the 1856 Flying Eagle Cent is categorically a pattern coin and not an official U.S. Mint issue, collectors have adopted the piece as a highly collectible rarity that is frequently collected alongside the 1857- and 1858-dated regular issues. The demand for this coin, with a mintage of an estimated 634 business strikes and about 1,500 proofs, far exceeds available supply. Prices start at around $7,000 for a G4 specimen and steadily increase from there up the grading spectrum.

The iconic key date of the Indian Cent series is the 1877 Philadelphia strike. It has a reported mintage of 877,000, which is the second lowest in the series – behind only the 1909-S at 309,000. However, as PCGS Price Editor Jaime Hernandez reports, numismatic scholars speculate how accurate the widely published 1877 mintage figure of nearly 900,000 really is. “There is only one reverse die confirmed as striking all existing 1877 Indian cents,” writes Hernandez. “However, if there was only one reverse die employed to strike all (877,000) 1877 Indian Cents, then this lone die should have sustained major planchet flaws when striking such a large mintage. Surprisingly, this is not the case since 1877 Cents show no traces of a damaged die. Therefore, it is strongly believed that the mintage of 877,000 coins struck is actually a highly inflated figure.”

At any rate, the 1877 Indian Cent offers a scant number of survivors. PCGS estimates approximately 5,500 exist, a number insufficient for satisfying strong generational collector demand. Collectors desiring a nice, moderately circulated specimen could obtain a F12 specimen for $1,350, while a handsome MS64RB takes nearly 10 times that amount, commanding $12,000.

The significance of the 1908-S Indian Cent lies not necessarily in its mintage – though at 1,115,000 it’s the third lowest of the business-strike arm of its series. This coin is numismatically historic because it was the first United States one cent coin struck at a branch mint, in this case San Francisco. As many numismatists know, it’s the branch-mint cents that lay claim to some of the biggest rarities of the denomination. Take, for example, the 1909-S Indian Cent and the 1909-S VDB and 1914-D Lincoln Cents, not to mention the scarce 1924-D and 1931-S Lincolns. Some may count the 1969-S Doubled Die Obverse Lincoln Cent among the other rarities from the “City by the Bay,” but that coin is rare due to its status as an elusive variety and not because of its S mintmark.

The combination of the 1908-S Indian Cent’s anemic mintage and noteworthy status as the first branch-mint “penny” makes it immensely popular with collectors. Thankfully, the coin is widely available in circulated and uncirculated grades, making it relatively affordable for collectors of diverse budgets. A nice example in F12 garners around $115, while a gorgeous MS64RB takes closer to $1,000.

There may be no more storied United States coin than the 1909-S VDB Lincoln Cent. It has been a “Holy Grail” for generations of Lincoln Cent collectors. It’s even well known beyond the fourth wall of numismatics – many non-collectors refer to the coin as “the 1909 penny” or “the 1909-S penny” and know it to be rare or “special.” Surely, many of these numismatic outsiders don’t know that the presence of designer Victor David Brenner’s “VDB” initials on the reverse really helps make this coin the rarity that it is. Numismatic lore says that the public felt Brenner’s relatively large “VDB” initials symbolized an audacious advertising campaign by the artist, but historians think the biggest “controversy” stemmed from some U.S. Mint and Treasury brass who took issue with the size and placement of the initials.

The Brenner brouhaha led Americans to believe that the VDB cents would be recalled, which never happened. However, the artist’s initials were dropped weeks after the first Lincoln Cents rolled off the presses, and the excitement over the 1909-S VDB Lincoln Cent hasn’t abated since. Only 484,000 examples of the 1909-S VDB Lincoln Cent were struck. PCGS estimates that some 50,000 exist, which is a respectable number that’s still far too small to quench collector demand. Prices for this key date hover around $1,100 in F12 and reach $8,000 in MS65RD.

The 1943 Steel Lincoln Cent isn’t a rare coin, but it’s one of historical and cultural significance given its connection to World War II. It’s the byproduct of war-era rations, which were necessary for supplying American and Allied troops with the artillery and other provisions they needed to win the war overseas. Copper was a particularly important commodity for producing ammunition. Thus, the U.S. Mint stripped the cent of its bronze composition. This followed suit with a similar move made in late 1942 to replace nickel – important for building tanks – with silver in the nation’s five-cent coin. Several governments around the world also employed emergency coin compositions to assist the war effort.

More than a billion 1943 Steel Lincoln Cents were struck among the Philadelphia, Denver, and San Francisco Mints. But they were only a one-year sojourn into the world of zinc-coated steel, as many in the public were dismayed by the appearance of rusty “pennies” in their pockets and purses. Worse yet? Many 1943 Steel Cents were apparently mistaken for dimes, and vice versa. By 1944, the war still raging on, the U.S. Mint returned to a 95% bronze composition; the copper was reportedly procured from reclaimed shell casings. While the 1943 Steel Lincoln Cent proved unpopular with much of America, it remains a historical wartime footnote and is an object of novel curiosity among both coin collectors and the non-numismatic public alike. The 1943 “steel pennies” from any mint facility are relatively affordable, with nice PCGSgraded specimens in MS65 trading for $30 to $40 apiece.

There are few “pennies” as famous as this one… Call it serendipity, but the 1955 Doubled Die Lincoln Cent was born by mere happenstance during the hobby’s boom time in post-war America. Millions were collecting coins, many searching through rolls and pocket change to build collections of Indian and Lincoln Cents, Buffalo Nickels, Mercury Dimes, and Walking Liberty or Franklin Half Dollars directly from circulation; Morgan and Peace Dollars could be purchased from many local banks for just a dollar. Veritably speaking, all eyes were on coins. So, when this drastic “error” began popping up as change in cellophane-wrapped 23-cent packs of cigarettes sold in vending machines accepting only quarters, they sent the American public into a numismatic frenzy.

Philadelphia Mint officials had the chance to prevent the 1955 doubled dies from ever escaping the Mint, where they were initially detected by coiners. A Mint inspector changed out the doubled die that was in operation on one of the coining presses. Of the 40,000 doubled dies that were estimated to have been struck, some 24,000 were already mixed into a larger batch of Lincoln Cents ready for distribution. It was decided to send the batch inadvertently salted with doubled dies on their merry way. After all, the doubled dies were seen by the Mint as “defects” – who would want them anyway? History went on to see the 1955 Doubled Die Lincoln Cent become one of the most famous of all die varieties and certainly the first to have been so widely prized and collected. Today, an AU50 specimen fetches approximately $2,400, while examples in MS63BN trade for closer to $9,000.

In 2017, the United States Mint celebrated the 225th anniversary of its establishment in 1792 by doing something that had never been done before. Mint officials placed the “P” mintmark on the Lincoln Cent. It was the first time a mintmark representing the Philadelphia Mint had ever appeared on the nation’s one cent coin. However, it would be only a one-year run. The “P” mintmark never made it back onto the coin after 2017. The coin surfaced quietly, released into circulation early in January 2017 with little initial fanfare. News of the coin broke when collector Terry Granstaff landed a 2017-P Lincoln Cent in change from a North Carolina gas station and posted their find on the PCGS Message Board. It wasn’t long before collectors were looking for the Phillyminted coin from sea to shining sea.

The P-mint Lincoln Cent garnered a price premium, with both single coins and rolls going for lofty sums, but eventually the hysteria waned. Today, the 2017-P Lincoln Cent trades for similar price levels as its counterparts of the mid- to late 2010s. A nice example in MS65RD goes for $16 while the more elusive MS68RD – a darling of PCGS Set Registry members – takes closer to $500. Regardless of price, the 2017-P Lincoln Cent represents an important numismatic chapter for the nation’s “penny.”

The United States Mint produced not just one or two, but rather three different kinds of Lincoln Cents at the West Point Mint in 2019. These three coins, one a business strike and the others taking the form of a regular proof and reverse proof, marked the first time the United States one cent coins ever bore the “W” mintmark of the West Point Mint. However, it was not the first time the cent had been produced by the upstate New York branch mint. The West Point facility, back when it was officially recognized as a bullion depository, produced millions of Lincoln Cents from 1974 through 1986 to assist the Philadelphia Mint with supplemental coinage. These West Point-minted Lincoln Cents of yore do not carry any type of mintmark and are wholly indistinguishable from Philly-struck Lincoln Cents of that same era.

While many collectors have handled dozens, hundreds, maybe even thousands of 1970s and 1980s Lincoln Cents from the West Point Mint through circulation channels, relatively few have the 2019-W Lincoln Cents. Only 346,117 business strikes were produced, while 600,423 regular proof strikes and 412,508 reverse proofs were minted. The business strikes were included as a bonus in 2019 United States Mint Sets; meanwhile, the proofs and reverse proofs were offered as premiums in the 2019 United States Mint Proof Sets and 2019 United States Mint Silver Proof Sets, respectively. The various iterations of the 2019-W Lincoln Cent in average Mint State and proof grades retail for between $15 to $25 each.

By Michael S. Fey, Ph.D.

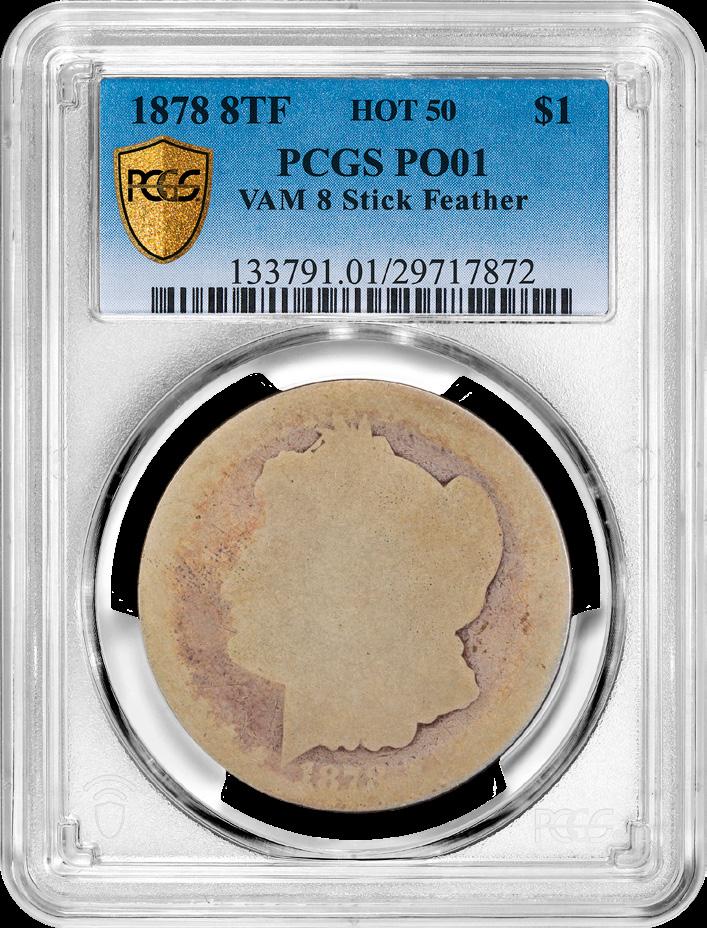

Perhaps the greatest numismatist of our time, Q. David Bowers, coined the term, “the joys of collecting.” This is a phrase that encompasses our need to collect, our need to be challenged, our need for recognition, our need to compete, and our need to have fun. Collecting low ball Morgan dollars is a testament to the many “joys of collecting.”

Low ball collector and co-author of The Cherrypickers’ Guide Bill Fivaz exclaimed, “This is a true form of collecting, and having fun is the appropriate idea. While out there hunting for rare die varieties, I

can also hunt for rare, low ball Morgan Dollars in dealers’ junk boxes and have fun while not breaking the bank.”

According to PCGS Grading Standards, the holy grail for low ball collectors is the example grading Poor-1, although a Fair-2 or About Good-3 may be acceptable as a filler until a lower-grading specimen is found. Coins are graded on a Sheldon Scale from 1 (the lowest grade discernible) to 70 (a supposedly “perfect” grade).

Low ball collectors will avoid ungradable coins, as no date or mintmark may be detectable. A Morgan Dollar graded About Good-3 will show rims worn into the tops of peripheral field lettering, but most remaining lettering will remain visible. A Fair-2 Morgan Dollar will show even more wear than an About Good-3, with only traces of the peripheral lettering visible. The Poor-1 Morgan Dollar, the holy grail, will just be barely identifiable as to type, date, and mintmark.

At this point, you may be saying to yourself, “I can do that!” However, according to Michael Hoyman, who is considered to be the “king” of collecting low ball Morgan Dollars, “Collecting low ball Morgan Dollars is every bit as challenging as collecting the finest gemgraded Morgan Dollar set. In some cases, there are fewer known Poor-1 graded Morgan Dollars than the highest-graded coins. Try finding any of the key date low ball Morgan dollars like the 1880-CC Reverse of 1878, the 1894 (Philadelphia strike), or the 1898-O, each with only one coin certified by PCGS in Poor-1.”

If you decide to target Morgan Dollar varieties, the challenge gets much tougher. For an appreciation of just how rare low ball Morgan Dollars are, I would urge you to look at the PCGS Population Census, available on the PCGS website.

There are many more collectors out there collecting low ball Morgan Dollars than you might think. Low ball collector Chris Lane said, “If you collect low Morgan Dollars, chances are good you are also collecting other types of low ball coins, including type sets, date sets, mintmark sets, and variety sets.”

Indeed, many collectors are vying for the lowest registry score in order to be recognized as having the Finest PCGS Registry Set. In the low ball set, you are awarded points, from 1-70, for the PCGS grades of your coins. Instead of targeting the highest-grading score, you want to be

as close as possible to the lowest score to garner Registry Set bragging rights.

Checking the PCGS website for the numbers of U.S. Low Ball Registry Sets, you can see that there are many different types of low ball sets. Morgan Dollar assemblages ranging from 12 sets for Top 100 VAMs to 1,081 sets for a Morgan Dollar Mint Mark Low Ball Set.

The Finest Basic Low Ball Morgan set of 97 coins listed on the PCGS website is the “End of the Trail,” with a PCGS Registry Score of 71.04 (as of June 2025), and was 100% complete. That set is listed in the PCGS Hall of Fame, having won

each year from 2012 through 2016. The “Reel Coug” collection, with a PCGS Registry Set Score of 71.04, and 100% complete, has been the current number #1 set from 2022 through 2024. This means that these collectors nearly completed the entire collection in Poor-1. No one has yet completed the entire set in Poor-1 with a 70.0 score and 100% complete.

If there appears in the market a coin in Poor-1 that these collectors need for their set, do you think they would be eager to buy it? Next time you come across a low ball coin, you may think twice about acquiring it.

It’s this competitive nature of building low ball Morgan Dollar sets that has pushed prices for many dates to stratospheric levels. A plethora of examples grading lower than About Good-3 have sold for multiples of what their Poor-1 counterparts would normally take.

For example, a 1903-O Morgan Dollar is worth around $435 according to the PCGS Price Guide. Yet, a PCGS-graded specimen grading Poor-1 hammered for an astounding $2,040 (with 20% buyer’s premium) in a May 2025 Heritage Auction event.

A key-date 1893-S Morgan Dollar in Good-4 is listed in the PCGS Price Guide for $3,900. However, one sold for $4,560 at a Heritage Auctions sale in November 2024.

An 1880-CC Morgan Dollar in Poor-1 realized $780 in August 2021, notching nearly three times more than its listed price of $270 in Good-4 in the PCGS Price Guide.

Remarked Philadelphia coin dealer

Andrew Edelman, who buys and sells coins every day, “It’s a nice break from the business and provides me with a lot of fun. Indeed, all the low ball collectors I’ve interviewed have expressed the same.” He continued, “[They] have expressed their imagination of just who may have touched these old cartwheels, had them in their pockets, and used them for the many financial transactions that lead to their excessive wear.”

Edelman concludes, “Collecting low ball Morgan Dollars is just plain fun to do.”

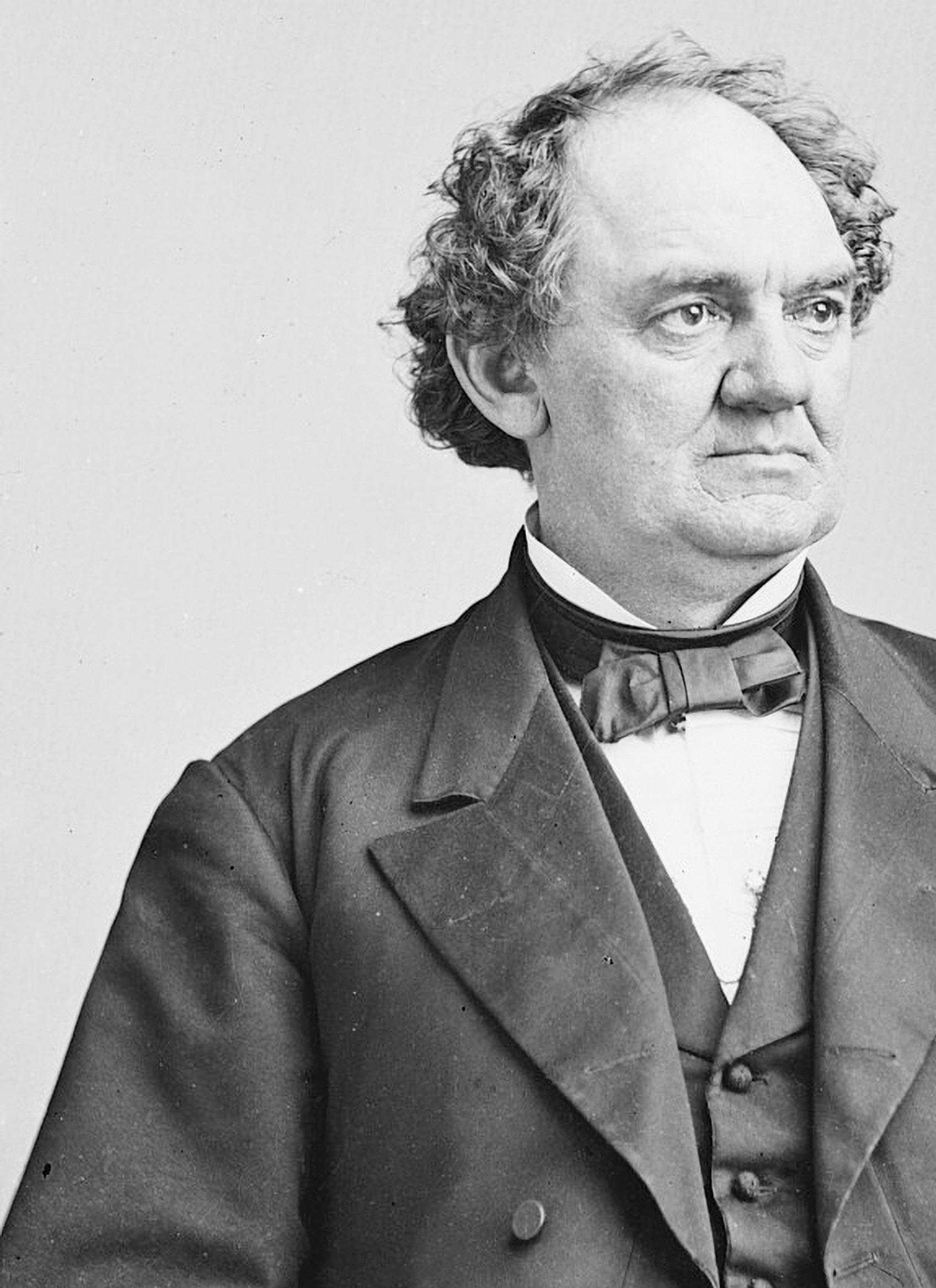

The city of Bridgeport, Connecticut, was officially incorporated as a city in 1836. One hundred years later, Representative Augustine John Lonergan of Connecticut brought a bill before the U.S. Senate to mint commemorative coins for the city’s centennial. The bill underwent multiple amendments before being approved, but it was eventually passed under the condition that no fewer than 25,000 coins be minted, and the proceeds from the sales would be allocated exclusively to centennial observances. They would also be allowed to mint these coins as long as they wanted, provided they maintained the date 1936.

In September of 1936, some 20,015 Bridgeport Commemorative Half Dollars were struck at the Philadelphia Mint. Henry Kreis was chosen as the designer for this coin because of his work designing the Connecticut Tercentenary Half Dollar the year prior. These coins were sold by the banks of Bridgeport instead of the U.S.

By Abigail Zechman

Mint because, at the time, commemorative coins were usually distributed by special interest groups or committees. The banks sold these coins for $2 a piece, which was a high cost at the time. Despite the price, they still sold well, grabbing the interest of both the public and collectors.

The obverse of this coin features a remarkably accurate portrait of the “Great American Showman,” P.T. Barnum. He was chosen for this honor because he helped develop Bridgeport into the bustling metropolis it is today, served as mayor, and is one of its most famous residents. It is also where he is buried. Many don’t realize that Barnum was a politician and a “profitable philanthropist,” in addition to being a businessman and circus owner. This is in large part due to his contributions to the city of Bridgeport and state of Connecticut being essentially left out of the historically inaccurate musical about Barnum’s life, The Greatest Showman.

In 1852, Barnum began investing in land to develop and expand Bridgeport, with the goal of transforming it into one of the most important cities in Connecticut. He bought and developed the land on the east side of the Pequonnock River,

which would eventually become the East Side of Bridgeport. Barnum utilized his business skills and connections to persuade successful manufacturers and large businesses to relocate to the agriculturally rich area, convincing them that it would become the new hub of the eastern seaboard. His work helped bring homes, commerce, and factories to the area, turning Bridgeport into the largest city in Connecticut.

Barnum didn’t stop there. As the city grew, so did his contributions. He partnered with some of the city’s other affluent residents to purchase a large plot of land and donate it to the city, which became Seaside Park, the largest park in Bridgeport, where a statue of Barnum now sits. He also played a significant role in establishing the first hospital in the

county and the Bridgeport-Port Jefferson Ferry, which allowed people to travel between Bridgeport and Long Island.

Having already served on the Connecticut General Assembly, Barnum was elected mayor of Bridgeport in 1875. During his term, he brought gas lighting to the streets and improved the water supply. After pausing his circus following some major setbacks, such as fires and train crashes, Barnum repartnered with an old friend in 1888 and relaunched Barnum & Bailey Circus. While it was a traveling circus, they decided to make Bridgeport their winter headquarters, drawing in crowds from all over. Barnum died in 1891 and was buried in Bridgeport. He had played a major role in growing the city’s notoriety, and it was his home.

The reverse of this coin features a highly controversial design. The subject, a majestic eagle, is not controversial on its own, but the way it was depicted is. Kreis chose a highly stylized and modernized eagle design that is disliked by many collectors. Some believe that this design is ridiculous and an insult to our national bird. In fact, many people think the eagle more closely resembles a shark or an airplane. If you rotate the coin the right way, the proud eagle becomes an ocean predator with two dorsal fins, more fitting for advertising a movie than symbolizing our country. On the other hand, some people feel that the stylized bird was a bold and inspirational choice, showcasing an exciting and new form of a well-known symbol of national pride.

By Abigail Zechman

“At the heart of inclusion is the belief that every person deserves to be seen, heard, and valued.”

~ Eunice Kennedy Shriver

Eunice Kennedy Shriver, the sister of President John F. Kennedy, was a philanthropist, activist, and the founder of the Special Olympics. She believed that individuals with intellectual disabilities could accomplish everything anyone else could if only given a chance, and she fought to provide them with opportunities.

Growing up, Shriver was very close to her sister, Rosemary, who had an intellectual disability. Shriver was inspired by her sister’s strength and resilience, which led her to become an outspoken advocate for individuals with intellectual disabilities. She was particularly impressed with Rosemary’s ability to keep up with their siblings during physical activities, which led to the development of “Camp Shriver” in 1962. This was a day camp Shriver hosted in her backyard for young people with intellectual disabilities, where she helped explore and develop their skills in physical activities and sports. She knew from her personal experiences that these individuals were capable of so much more than anyone thought and wanted to help them feel seen, build community, and showcase their skills.

Shriver’s camp continued to grow, eventually leading to the development of the Special Olympics in 1968. The first International Special Olympics Summer Games were held in Chicago with over 1,000 athletes from the U.S. and Canada. Over 200 different athletic events were offered. Following the success of the inaugural games, the Special Olympics were officially incorporated, and the foundation was established, enabling the organization to continue and grow into what it is today. Since then, almost three million athletes from all over the world have competed in the games.

Shriver’s advocacy for people with intellectual disabilities didn’t stop there.

In 1969, she moved to France to advocate for her cause and lay the groundwork for the Special Olympics’ extensive international expansion. In 1982, she founded the “Community of Caring” character education program, focusing on disabilities, which was adopted by nearly 1,200 schools nationwide. She spent her whole life fighting for better support for individuals with intellectual disabilities.

In 1984, Shriver received the Presidential Medal of Freedom and, in 1998, was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame. In 2009, she received a

portrait in the National Portrait Gallery (NPG). Shriver saw the first portrait commissioned for the NPG as someone who was not a president or first lady.

In 1995, the United States minted a silver dollar to commemorate the Special Olympics World Games. There was initially some controversy around this design because many felt that it was too focused on Eunice Kennedy Shriver.

But, it was decided that, since she was the founder of the Special Olympics, it was appropriate to feature her portrait on the obverse. Shriver became the first living woman featured on a U.S. coin.

The reverse features a medal from the games, a rose, and this quote by Shriver: “As we hope for the best in them, hope is reborn in us.” The design on the medal features the Special Olympics logo, with five people standing in a circle, symbolizing the organization’s global presence. All the figures have three arms: the lowered arms represent a time when people still underestimated the talents of individuals with disabilities, the straight arms represent outreach, and the raised arms represent joy and accomplishment. The rose is a tribute to Shriver’s sister, Rosemary, who inspired the idea for the Special Olympics.

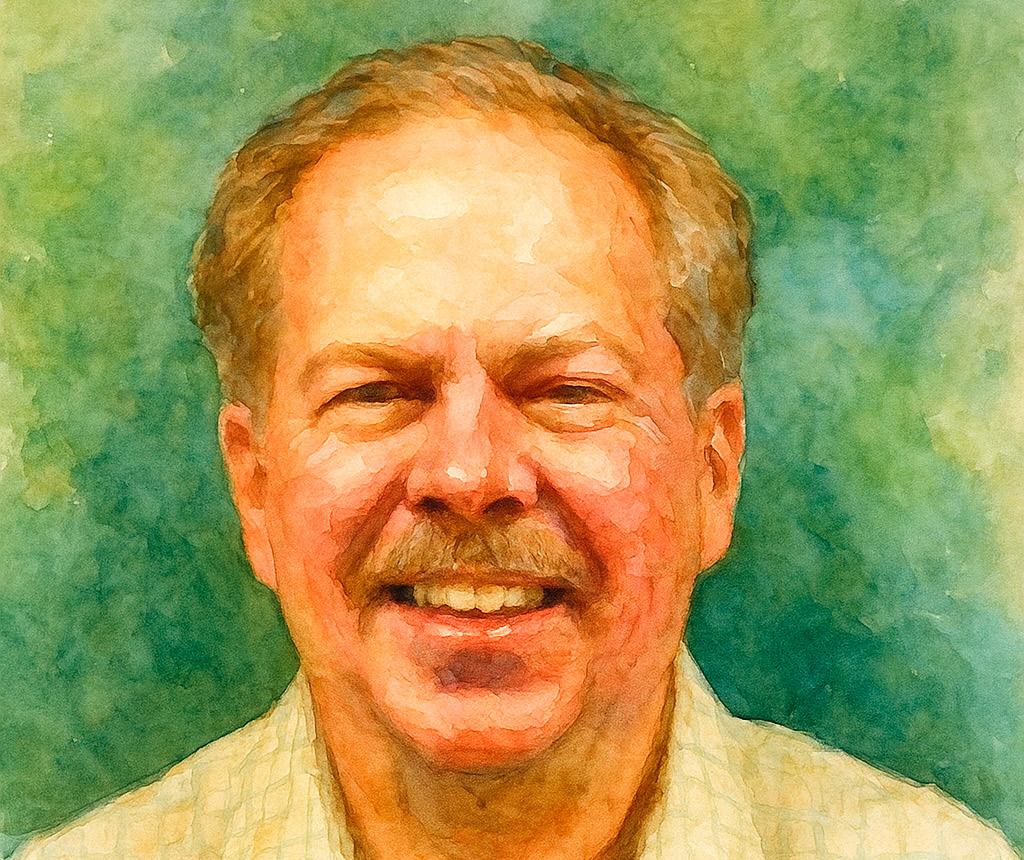

By Joshua McMorrow-Hernandez

A seven-year-old Jeff Nicholson found his numismatic calling with Lincoln Cents in the early 1970s. “Not really sure why I chose coins at the time other than wanting to do something different than my brother, 15 months older, who had a stamp collection,” recalls Nicholson. “My father, a teacher, would have the lunchroom ladies save any Wheat Cents that they found and would usually bring me home several each day.” Young Jeff studied coin magazines and A Guide Book of United States Coins (“The Red Book”) and spent hours at his local coin shop perusing the inventory while talking coins with the dealer. The budding numismatist also searched numerous coin rolls for his growing collection. “I had the great fortune of finding all the Lincoln Wheat series in this manner, minus the big four (1909-S, 1909-S VDB, 1914-D, and 1931-S). After a couple of years, allowance and chore monies were saved up, and the final four were purchased at one time, completing the collection.” He sold that first Lincoln Cent set as he grew into his teens, when he found other pursuits that attracted his attention.

Nicholson returned to the hobby about 25 years ago. His love for vintage Lincolns remained. “I have always loved copper coins and especially the Wheat reverse of the Lincoln Cent.” His PCGS Registry Sets grew slowly with high-quality Lincoln Cents. His patience and keen desire for quality lifted his four Lincoln Cent PCGS Registry Sets under the “Sage Oak” banner to lofty heights. “I never thought I could make it into the top 10 of sets due to the competition involved, but with several key coins becoming available over the last few years from top sets, my Lincoln Cents Basic Set, Circulation Strikes (1909-1958) is #1.”

Some coins were tougher to locate than others. Those posing Nicholson the greatest challenge? “Most ‘S’ mints in the ‘20s,” he quickly replies. Yet, years of diligent set building have paid

off for Nicholson. His carefully curated sets boast many gems, such as his 1909-S VDB, which grades PCGS MS67RD. “It has amazing color for an ‘S-VDB.’”

Nicholson attributes his success to patience and finding a dealer he could trust. “Andy Skrabalak at Angel Dee’s Coins and Collectibles took the time to teach me about coin quality and grading at high levels,” he says. “Learn a series and what a quality coin in that series looks like.” He also recommends spending a little more money to obtain the quality you really want. “If you aren’t in love with a coin when you buy it, you won’t like it later. Cheap coins are usually cheap for a reason.” It may become even harder to find high-quality Lincoln Cents in the future, especially as production of the coin is slated to end soon. “It’s sad to see it go, but it is definitely time.” Nicholson says the coin’s buying power has shrunk too much. But he’s hopeful for what the future may hold for the cent in its pending obsolescence. “For the Lincoln series specifically, it should bring out some new collectors, hopefully, but I think the focus will be on Lincoln Memorial Cents mainly as it has been 67 years since the Wheat Cent was discontinued.”

By Joshua McMorrow-Hernandez

Garrett Ziss entered numismatics as the result of a second-grade school project back in January 2011. “We were required to bring a dollar’s worth of coins into school to learn how to count money,” recounts Ziss, now 22. “Many of the other kids and I started to look at the dates on the coins as well as their designs, especially for the state quarters. I asked my parents to look through their change and found three 1941 Nickels, which became my first coins.”

Garrett was soon helping his dad roll loose change and was allowed to keep several interesting coins, including a 2006 Lincoln Cent with a mason counterstamp. “In May, for my eighth birthday, my parents bought me a copy of A Guide Book of United States Coins [“The Red Book”] and Fascinating Facts, Mysteries & Myths About United States Coins by Robert R. Van Ryzin. I spent the summer reading both books over and over again.”

Ziss enjoys many facets of the hobby, especially numismatic history as viewed through an economic lens. “This tie-in to economic history is an interesting way to align my passions for numismatics and economics, and can also make coins significantly more interesting!” He also likes the history of how coins were made. “Learning about the history behind coins also includes the artistry and technology involved in their manufacture.”

Furthermore, he is fascinated by another aspect of numismatic history: provenance – the chain of ownership that one can trace back for a specific specimen. “I am trying to obtain coins with as many different pedigrees as possible from collectors in that series.” He adds, “Learning about the collecting tradition via provenance is very important to keep the hobby alive and contiguous for future generations.”

Bringing more people into the numismatic fold has long been important to Ziss,

who in 2017 became the first young numismatist to give a Money Talks presentation at the American Numismatic Association World’s Fair of Money. “In total, I have given presentations to five different national numismatic organizations, which I am very proud of.” He serves as the assistant editor of digital numismatic publication The E-Sylum and is a U.S. coin cataloger for Heritage Auctions.

In his downtime, Ziss loves collecting and studying early Federal-era copper as well as Capped Bust Quarters and Capped Bust Half Dollars. “My favorite coin from the Bust series is a double-struck 1809 O-107 half dollar with dentil tracks over the cap,” he says, noting that the coin was previously cataloged as the distinct and semi-unique 1809 O-107 “a” subvariety. “I am also continuing my longterm research on Bust and Liberty Seated coin images on obsolete paper money, as well as conducting further numismatic research in various areas, some of which is for a larger, longer-term numismatic project that is still in the works.”

He encourages other collectors to learn as much as they can about their favorite areas of the hobby. “There are many different paths that numismatics can lead you down that tie back into your non-numismatic interests. It can also lead you down new roads, like the myriad of interesting anecdotes I have learned about American local history through my study of obsolete paper money. Either way, you will gain a deeper understanding of the history of the area from which you collect coins.”

By Edward Van Orden

The United States Treasury Department has set in motion a plan to discontinue production of the one cent coin next year. In continuous circulation since first being struck in 1793, the cent is one of the first denominations produced by the U.S. Mint. Having been struck in numerous sizes, styles, and compositions, these iterations have not only popularized coin collecting by way of numerous transitions but also through a wealth of varieties to boot.

Struck for circulation starting in 1793, the “large cent” measured from between 26 to 29 millimeters in diameter and was made of 100% copper. Perhaps the most famous and desired variety of the series is the 1794 Starred Reverse. Also known as Sheldon-48, the Starred Reverse features 94 roughly equidistant stars around the perimeter (7 of which are hidden by dentils). Why this 1794 Large Cent reverse was made with stars remains a mystery. However, it has been speculated that planchets originally struck for the 1792 quarter pattern reverse went unused and were later overstruck with the 1794 design. About 50 to 60 specimens have been identified since their discovery in 1877.

Due to the rising cost of production (sound familiar?), the size of the cent was reduced to 19 millimeters during 1857, and no longer made of 100% copper. This new “small cent” design, however, was immediately popular and gave numismatics a surge in popularity by creating nostalgia for the disappearing large cent. Three of the most curious 1857 Flying Eagle varieties feature clash marks with other denominations. One of them, recognized as Snow-7, has clashed through “AMERICA” the profile of Liberty from the Double Eagle. The other two multi-denomination clashed dies, cataloged as Snow-8 and Snow-9, show clash marks corresponding to the Liberty Seated Quarter and Liberty Seated Half, respectively. Easy to spot even in lower circulated grades, it is unknown to this day why these fascinating varieties came to exist.

The Flying Eagle design, while popular with the public and numismatists alike, was replaced only two years later in 1859 with the second of the small cent designs, the Indian motif. Struck until 1909, this series features varieties as dramatic and aesthetically curious as those of any U.S. series. One of them is the eye-catching 1873 Doubled Liberty. Known as Snow-1/1b, this “Closed 3” 1873 variety features prominent doubling of “LIBERTY” as well as the headdress feathers and Liberty’s portrait (with the eye and lips still prominent on worn examples). Only about 400 to 500 of this popular “Red Book” variety (one listed in A Guide Book of United States Coins) are known to exist, few of which were preserved in Mint State.

The third and final small cent design is the one currently featuring Abraham Lincoln’s profile. First struck in 1909, the Lincoln Cent series includes two of the rarest and most desired varieties in all of numismatics, the 1958 and 1969-S Doubled Die Obverses. This series also includes collectible subsets of varieties known as the “Wide AM” and “Close AM” reverses. The reverse design for proof Lincoln cents, featuring the spaced apart or “wide” AM of “AMERICA,” along with a flared vertical bar in the G of the designer’s initials, were accidentally used for some 1988, 1988-D, 1998, 1999, and 2000 business-strike issues, with the rarest being 1999. The reverse design for 1993 Lincoln Cents, featuring the closely spaced or “close” AM of “AMERICA” and accompanied by a straight vertical bar in the G of the designer’s initials, was inadvertently used for some 1992 and 1992-D business strikes, as well as on some 1998 and 1999 proofs. The 1992 is the rarest known so far.

By Jaime Hernandez

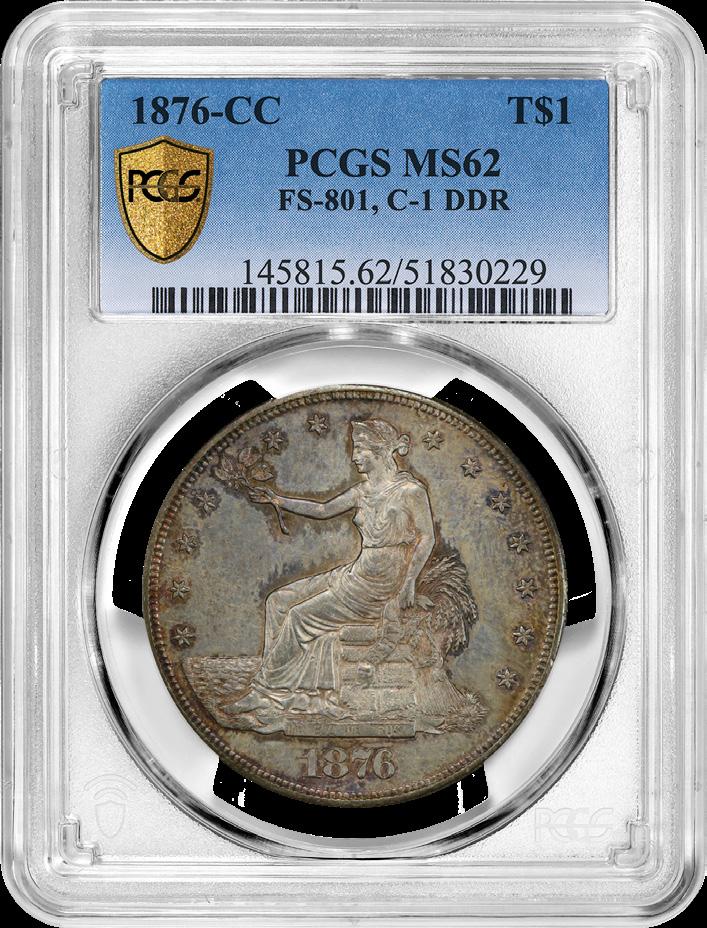

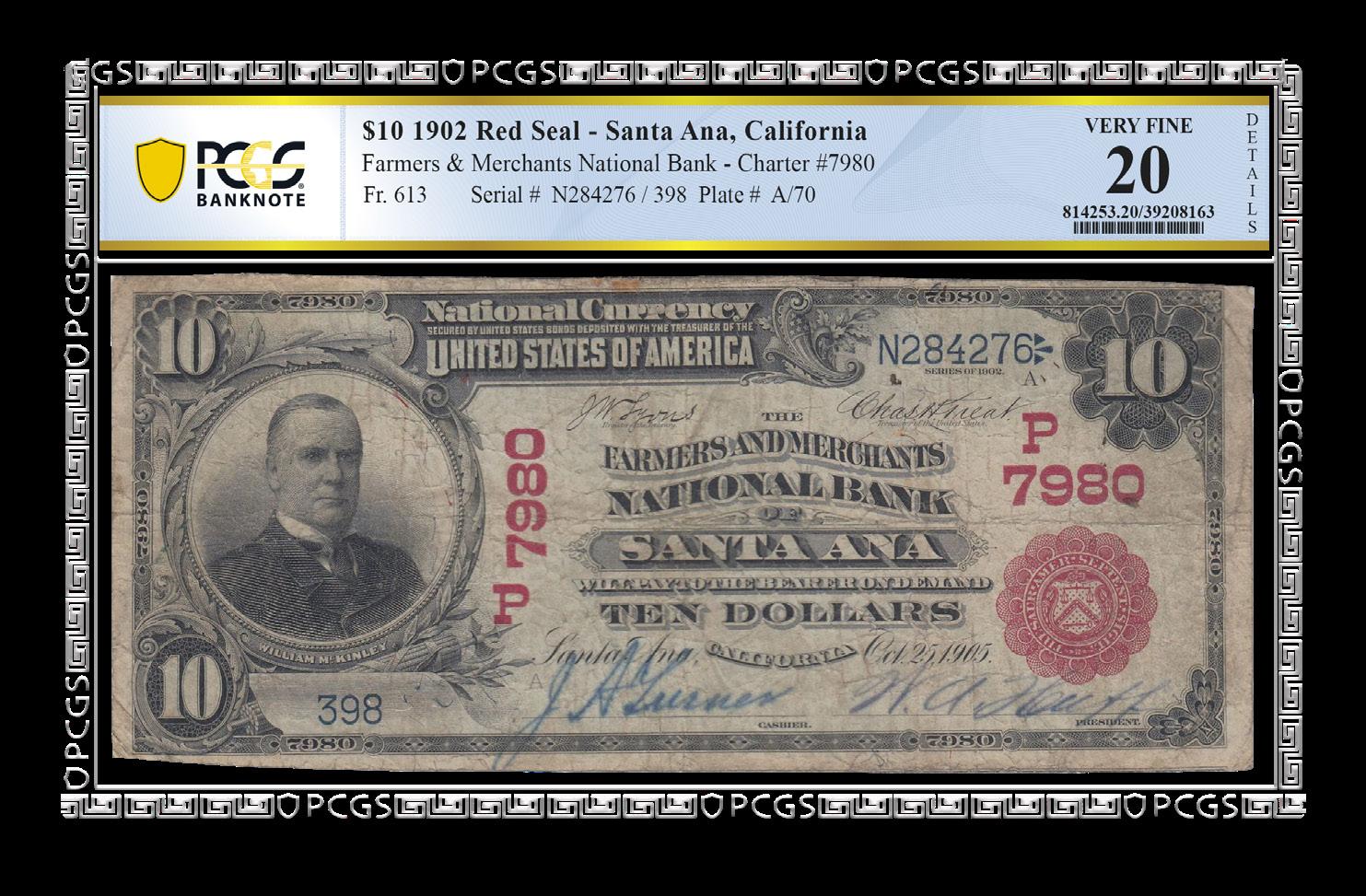

We are halfway through 2025, and the rare coin and banknote auction markets show no signs of slowing down. Indeed, with higher bullion price levels and strong demand, auction prices realized have been quite impressive on most rare coins and banknotes. Below are some of the great coins, as well as a great banknote, that we would like to highlight.

1869 Copper Plate by John Adams Bolen, PCGS MS64BN

One of only two struck by John Adams Bolen in 1869, this plate is the only example available for public ownership. The only other example is housed in the Massachusetts Historical Society Collection. This specimen, Bolen’s personal example, is curious in that no one knows for certain exactly what Bolen intended with the striking of this piece.

Indeed, it displays two impressions from the LIBER NATUS LIBERTATUM obverse, one of which is an early die state, while the second is terminal with a retained cud over ATEM. Even more curious are the incomplete representations of potential types or mulings. Just looking at the reverse Bolen impressions in a clockwise manner include JAB-37, JAB

M-11, JAB-37, and JAB-36. This nearly unique plate has only sold twice in the last 140 years with the new owner obtaining an exceptionally rare piece for the price of $4,800 in a Stack’s Bowers Galleries sale.

Most often die doubling is minor and hard to discern for many numismatists. What makes this 1876-CC Trade Dollar FS-801 Doubled Die Reverse so special is the degree of the offset to the doubling. In 2012, numismatic author Q. David Bowers wrote the following about this variety: “Regarding the doubled die reverse Trade Dollar offered here, [variety expert] Bill Fivaz and I corresponded

on this variety years ago, and he said it was the most spectacular doubled die in American coinage.” Pay special attention to the bottom of the right eagle’s wing as well as the branches upon which the eagle is standing. You will be amazed at the doubling on the reverse of this cool coin, which notched $13,800 at a Stack’s Bowers Galleries auction.

National Banknotes allow collectors to focus on issues of their hometown or state. Like all paper currency, these banknotes all have unique serial numbers. They also possess National Bank Charter numbers unique to the particular National Bank as well as its local bank name, city, and state, listed prominently on each bill. This 1902 $10 Red Seal Note from the Farmers and Merchants Bank of Santa Ana, California, is Charter #7980 and was graded VF20 by PCGS Banknote. This note represents the only Red Seal from this tough, shortlived California charter. The Farmers and Merchants Bank issued National Bank Notes for only 14 years before closing in 1919. Just six total notes are known on this scarcest of Santa Ana banks. Only two of those six notes have been offered publicly since 1990. This specimen sold for $3,360 in a Heritage Auctions offering.

By Jay Turner

As a fledgling colony, Australia faced a major problem: lack of money, specifically coinage for use in commerce. The colonial population of Australia would use any foreign coin or even barter for their transactional needs. Attempts to control commerce by the colonial government failed in both the valuation of foreign species and in attempts to prohibit barter of rum. It wouldn’t be until 1812 when the government of New South Wales, Governor Lachlan Macquarie, was sent 40,000 Spanish 8 reales on the HMS Samarang from the East India Company. These coins were used to fill the need for New South Wales, Australia.

New South Wales faced a problem that many other colonies faced – keeping the coinage domestic and preventing its export. Much like areas in the Caribbean, Australia chose to cut and countermark these Spanish “Dollars” to keep them in New South Wales. A convicted forger named William Henshall was given the task of cutting and countermarking the 40,000 coins. The center was cut out of

each coin, and the resulting inner hole of the dollar was counterstamped “New South Wales 1813” on the obverse and “Five Shillings” on the reverse. The center cut of the coin, also known as the dump, was also stamped over with dies featuring a crown and “New South Wales 1813” on the obverse and “Fifteen Pence” on the reverse. The valuation of these coins combined was six shillings, three pence, which was a full 25% higher than the actual value of the intact Spanish 8 reales. This kept the coins in New South Wales by removing the incentive of exporting.

It took over a year for the coins to be converted, and the total mintage was 39,910 holey dollars and dumps. By decree of July 1, 1813, the coins became legal tender in New South Wales, becoming Australia’s first struck coins. The coins were successful in elevating the needs of the colony. By 1822, the import of British coins had become more frequent, and the holey dollars and dumps started to be removed from circulation by the government. In 1829, the coins would

be officially demonetized. It is believed that the majority of the coins were successfully removed and melted down.

Today, an estimated 350 holey dollars and 1,500 dumps are believed to still exist. At the beginning of 2025, one of these surviving pieces was submitted to the PCGS office in Hong Kong. Because the origin of the Spanish 8 reales came from Madras, India, all the coins were mixed from different mints and years, making each surviving piece scarcer when taking the host into account. This example used the host of a Mexico City Mint Charles IV issue dated 1789. In previous auction records, only two other examples from this host have been noted since 2011. This coin was evaluated by PCGS and graded VG08, with the countermarked portion being of VF Details. Rare and desirable in any condition, this outstanding survivor was a highlight of this Hong Kong Express submission and is now protected for the future by PCGS.

By Philip Thomas

Habemus papam… We have a pope! It has only been a matter of months since a plume of white smoke billowed up from the humble metal chimney of the Sistine Chapel rooftop, signifying that a two-thirds voting majority was successfully achieved by the sequestered papal conclave. This College of Cardinals had, in accordance with the centuries-old Roman Catholic Church tradition, visually demonstrated to the tens of thousands of faithful gatherers anxiously waiting outside that a new pope had been elected.

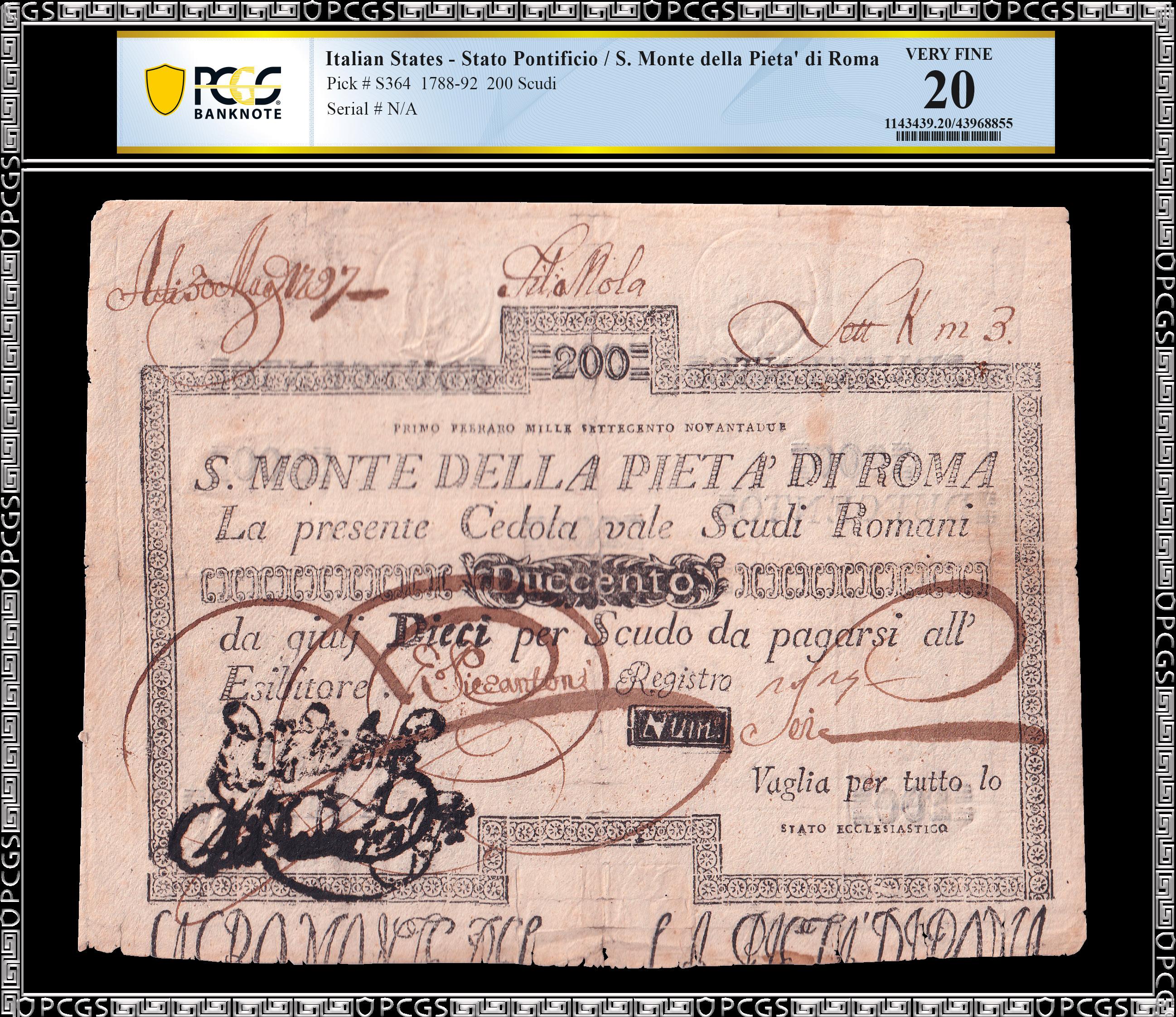

On that day, American Cardinal Bishop Robert Francis Prevost, known now by his papal name Leo XIV, had become both the spiritual leader of the world’s 1.4 billion Catholics as well as the sovereign head of the Vatican City State. To commemorate this once-in-ageneration phenomenon of appreciable global interest and impact, this installment of Notable Notes will take a look at a lovely late-18th-century, large-format, higher-denominated Papal States paper currency issue and delve into some of the fascinating associated regional history and geography.

While it is widely known that the Vatican is the smallest autonomous microstate on Earth in terms of both land area (just

0.18 square miles) and population (less than a thousand inhabitants), its origin story and precursory configurations aren’t exactly a matter of common knowledge. The 1929 signing of the Lateran Treaty between Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini and the Holy See under Pope Pius XI established Vatican City as we know it today. Prior to that, and before the preceding 60-year period of Italian unification that saw almost no territorial reign by the church, popes took on the functions of secular government firsthand, maintaining independent rule over large swaths of the central Italian peninsula for over a thousand years. These land regions were known as the Papal States, and they endured from about 756 until their demise in 1870.

Of course, a critical part of governance involves keeping economies humming and overseeing the production of circulating monetary instruments required to make that happen. A handful of quasi-private commercial institutions within the Papal States, along with their treasury, printed and circulated hundreds of different notes of varying designs, currency units, and denominations between 1785 and 1870, the majority of which remain rather cost-accessible and well-preserved for collectors to enjoy today.

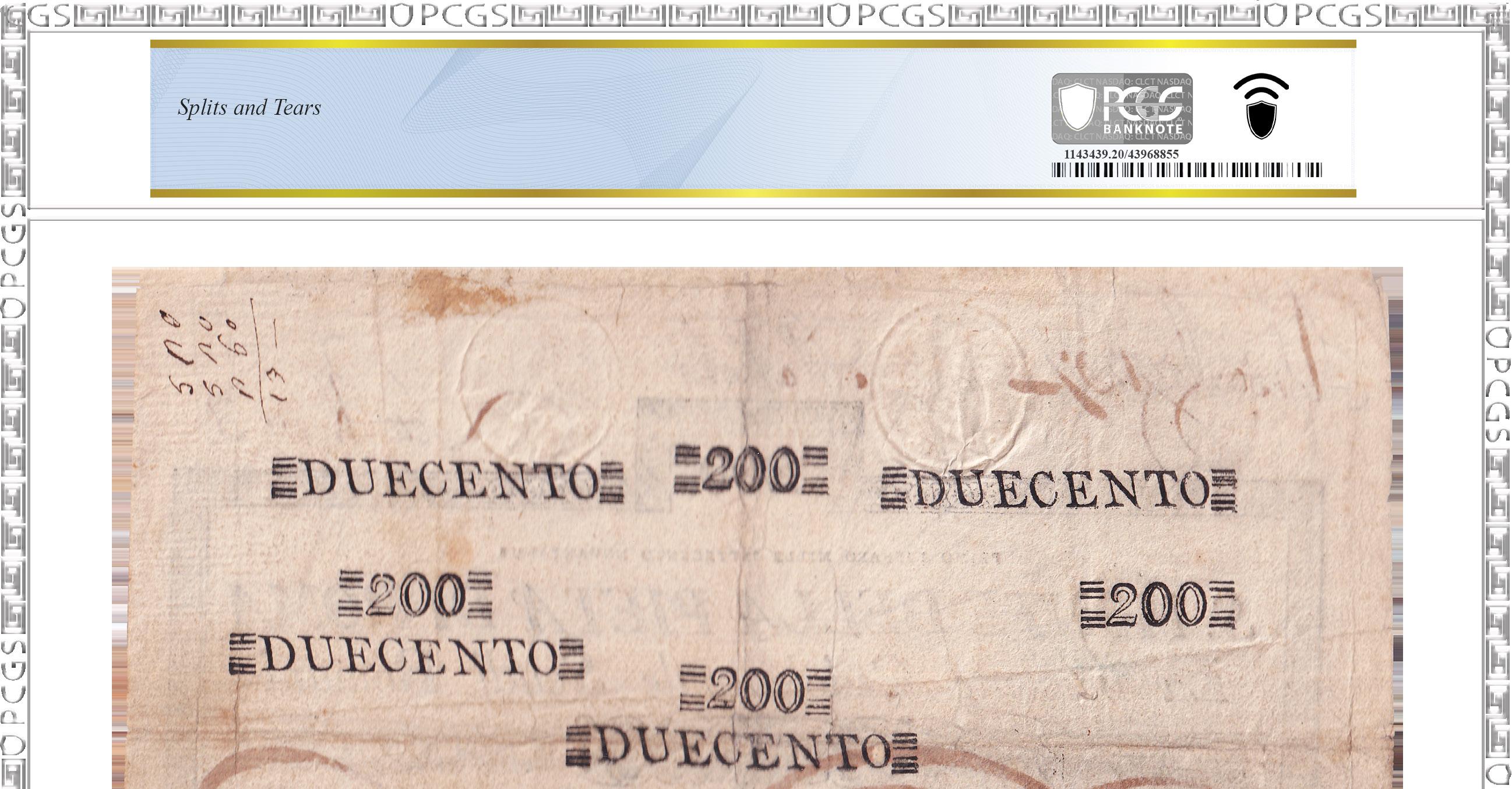

We present one stellar example: a 200 Scudi issued between 1788 and 1792 by Sacro Monte della Pieta’ di Roma.

Sacro Monte della Pietà di Roma, in and of itself, holds a unique and interesting backstory. Formed in 1539 by Pope Paul III as a sort of pawnbroking service to supply zero-interest loans to the impoverished, the physical footprint of the sprawling complex existed in Rome’s Regola district, just a mile or two southeast of modern-day Vatican City. Over time, the facility grew into providing other forms of financial and banking services, including the issuance of the types of paper currency showcased here.

Graded Very Fine 20 by PCGS Banknote, this eye-pleasing example, with its ornamental block frame, fancily scripted obligation in Italian, numerous fountain pen-applied authorizing and endorsing signatures, dual circular embossments up top, and intricate paper watermarking throughout, would certainly make the new pope very proud.

By PCGS Staff

After much anticipation in the numismatic community, the time has finally come to announce that PCGS has launched grading services for ancient coins. Ancient grading began early in August and has kicked off with a variety of Chinese cash coins representing the Qing Dynasty. These Qing Dynasty cash coins are among the most popular ancient coins and are collected by countless numismatists in China and throughout the rest of the world.