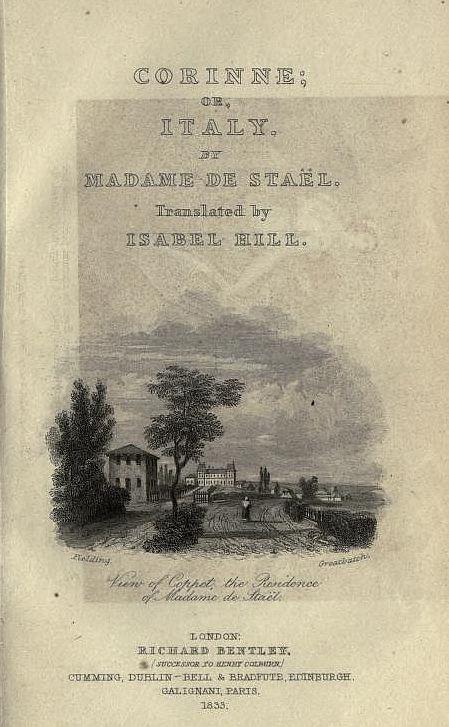

MADAME DE STAËL

TRANSLATED BY ISABEL HILL; WITH

METRICAL VERSIONS OF THE ODES BY L. E. LANDON

LONDON:

RICHARD BENTLEY, NEW BURLINGTON STREET, (SUCCESSOR TO HENRY COLBURN).

1833

Contents

Translator's Preface.

Whatever defects may exist in my attempt at rendering "Corinne" into English, be it remembered, that we have many words for one meaning—in French there are several significations for the same word. Repetition, an elegance in French, is a barbarism in English. Thus I had to contend with a tautology almost unmanageable, and even a reiteration of the same sentiments. Sentences, harmonious in French, lost all agreeable cadence, until entirely reconstructed. Madame de Staël's diffuse manner obliged me also to transpose pretty freely. I found, in so doing, many self-contradictions, some of which I could not efface. Her boldness of condensation, too, and love of vague, mysterious sublimity, often left me in doubt as to

what might be hidden beneath the dazzling veil of her eloquence. It may appear profanation to have altered a syllable; but, having been accustomed to consult the taste of my own country, I could not outrage it by being more literal. I have taken the liberty of making British peasants and children speak their native idiom, and have added a few explanatory notes; occasionally availing myself of quotations from more recent authorities than that of the Baroness. Lest I should unconsciously have committed any great mistake, be it known that the printers of her "eighth corrected and revised edition" gave Corinne a military instead of a literary career, and made the Roman mob throw handfuls of bon mots into the carriages during the carnival.

Miss Landon had kindly undertaken to render the lyric portions of the work; but we feared for awhile, that our own Improvisatrice would be prevented by circumstances from gracing the volume by her name. I, therefore, translated Corinne's compositions into rhyme. Only one of my essays, however, "The Fragment of Corinne's Thoughts," was required. I am conscious of its imperfect regularity; but, having no poetical reputation at stake, I throw myself on the mercy of my judges.

ISABEL HILL.

6, CECIL STREET, STRAND.

MADAME DE STAËL.

Madame de Staël—Her Infancy and Education—Her Marriage—Her Personal Appearance—The Revolution—Her First Meeting and Conversation with Bonaparte—Interview with Josephine—Her Portrait and Character—Her Repartees—Exile—Delphine—Auguste de Staël and Napoleon—Private Theatricals—Corinne—Police Interference—Travels in Foreign Countries—Her Illness and Death—

Effect of Napoleon's Persecution upon the Literary Position of Madame de Staël.

Jacques Necker, the father of Madame de Staël, a Genevese and a Protestant, was at the birth of his daughter Annie-Louise-Germaine Necker, in 1766, a clerk in a banking-house at Paris. He had married M'lle Curchod, a Swiss like himself, and who had, some years before, been the object of the first and last love of Gibbon the historian. Madame Necker undertook the education of Louise, plied her with books and tasks, and introduced her, even in infancy, to her own circle of brilliant and accomplished men. "At the age of eleven," writes a lady who was at the time her companion, "she spoke with a warmth and facility which were already eloquent. In society she talked but little, but so animated was her face that she appeared to converse with all. Every guest at her mother's house addressed her with some compliment or polite speech; she replied with ease and grace." She was encouraged to write, and her youthful productions were read in public, and some of them were even printed. This process of education, while it rendered the subject of it rather brilliant than profound, and encouraged vanity and a love of display, broke down her health, and the physicians ordered her to retire to the country, and to renounce all mental application. Her mother, disappointed and discouraged, ceased to take the same interest in her talents and progress; this indifference led Louise to attach herself more closely to her father, and developed in her what became through life her ruling passion—filial affection.

In 1776, Necker, who had in the meantime become the partner of his late employer, and had attracted attention by an essay on the corn laws, was considered by the masses as the only person capable of saving the country from bankruptcy. He was, therefore, appointed to control the finances, being the first Protestant who had held office since the revocation of the Edict of Nantes. One of his acts, five years afterward, having excited clamor among the royalists, an anonymous pamphlet appeared, in which his defence was warmly

espoused and the propriety of his conduct successfully asserted. Necker detected his daughter's style in this production, and she acknowledged its authorship, being then fifteen years old. Necker resigned office, and retreated with his family to Coppet, on the borders of the Lake of Geneva.

Madame de Genlis saw M'lle Necker for the first time, when the latter was sixteen. She thus speaks of her in her memoirs: "This young lady was not pretty; her manner was very animated, and she talked a great deal, too much indeed, though always with wit and discernment. I remember that I read one of my juvenile plays to Madame Necker, her daughter being present. I cannot describe the enthusiasm and the demonstrations of M'lle Louise, while I was reading. She wept, she uttered exclamations at every page, and constantly kissed my hands. Her mother had done wrong in allowing her to pass three-quarters of her time with the throng of wits who continually surrounded her, and who held dissertations with her upon love and the passions."[1]

At the age of twenty, Louise married Baron de Staël-Holstein, the Swedish ambassador at the court of France. She sought neither a lover nor a friend in her husband; she treated marriage as a convenience, and became a wife in order to obtain that liberty and independence which were denied her as a young lady. She required that her husband should be noble and a Protestant, and as in addition to these essentials Baron de Staël was an agreeable and an honorable man, and engaged never to compel her to follow him to Sweden, she consented to marry him. In the same year, 1786, a failure of the crops, and the consequent distress of the poorer classes, compelled the king to recall Necker to the administration of the finances.

Madame de Staël is thus described, at the age of twenty-five, by a writer who, to justify the peculiar and oriental extravagance of his style, assumed the character of a Greek poet: "Zulmé advances; her large dark eyes sparkle with genius; her hair, black as ebony, falls on her shoulders in wavy ringlets; her features are more striking than

delicate, and express superiority to her sex. 'There she is,' all exclaim when she appears, and at once become breathless. When she sings, she extemporizes the words of her song, the ecstasy of improvisation animates her face, and holds the audience in rapt attention. When the song ceases, she talks of the great truths of nature, the immortality of the soul, the love of liberty, of the fascination and danger of the passions. Her features meanwhile wear an expression superior to beauty; her physiognomy is full of play and variety. When she ceases, a murmur of approbation thrills through the room; she looks down modestly; her long lashes sink over her flashing eyes, and the sun is clouded over."

The Revolution now advanced with rapid steps. Necker, whose capabilities as a financier have been generally acknowledged, was totally deficient in the higher qualities of the statesman. He sought to assume a middle position between the court and the people, but failing of success, was in consequence dismissed on the 11th of July, 1789. Paris rose in insurrection when this event became known, and on the 14th, the Bastille was in the hands of the people. The king was forced to send an order to recall Necker, who had left the country; this overtook him at Frankfort. "What a period of happiness," writes Madame de Staël, "was our journey back to Paris! I do not believe that a similar ovation was ever extended to a man not the sovereign of the country. Women, afar off in the fields, threw themselves on their knees, as the carriage passed: the most prominent citizens acted as postilions, and in many towns people detached the horses and dragged the carriage themselves. Oh, nothing can equal the emotions of a woman who hears the name of a beloved parent repeated with eulogy by a whole people!" This triumph was of short duration. In a little more than a year, Necker, who had opposed some of the more radical measures of reform in the National Assembly, lost the confidence of the people, resigned, and again withdrew to Switzerland. He was now accompanied by the revilings and maledictions of the populace, and even narrowly escaped with his life.

Madame de Staël remained at Paris, and speedily became involved in the intrigues of the day. Her salon was the rendezvous of the royalists and Girondins, and the scene of ardent political discussions. In the midst of the sanguinary excesses of '92, she fearlessly used her influence to shelter and save her friends. She took them to her own house, which, being the residence of an ambassador, she presumed would be inviolable. But one night the police appeared at the gate, and required that the doors be opened for a rigid search. Madame de Staël met them at the threshold, spoke to them of the rights of ambassadors and of the vengeance of Sweden, and by dint of wit, argument and intrepidity, persuaded them to abandon their designs. She was soon compelled to flee, however, and take refuge with her father at Coppet. Here she wrote and published an appeal in behalf of Marie Antoinette, and "Reflections on the Peace of 1783." The fall of Robespierre, in July, 1794, enabled her to return to Paris, whither she hastened, upon the news of his execution.

Her residence in the capital formed an event in the annals of society at that period. The most distinguished foreigners and the best men in France flocked around her. She gave her influence to the government of the Directory, being desirous of the establishment of some guaranty for the preservation of order and of individual security.

"Madame de Staël," says de Goncourt, "was a man of genius as early as the year 1795. It was by her hand, that France signed a treaty of alliance with existing institutions, and for a period accepted the Directory. Who obtained her the victory? Herself, with the aid of a friend who was the scribe of her dictation, the aid-de-camp and the notary-public of her thought, Benjamin Constant. The daughter of Necker forbade France to recall its line of kings: she retained the republic: she condemned the throne. She agitated victoriously in behalf of the maintenance of the representative system. The human right of victory was equivalent, with her, to the divine right of birth." [2]

The appearance of Bonaparte upon the stage of action produced a violent change in her life, pursuits and pleasures. She disliked and distrusted him from the first, and her drawing-room became an opposition club, or, as Napoleon himself described it, an arsenal of hostility. He, in turn, was vexed at her intellectual supremacy, and dreaded her influence. They first met at a ball given to Josephine, toward the close of the year 1797. She had long hunted him from place to place, for she was desirous of subjecting him, if possible, to the fascinations of her conversation, and he, avoiding the interview with consummate address, had always escaped her importunities. At the ball in question, he saw retreat to be impossible, and boldly seated himself in a vacant chair by her side. The following conversation, attributed to them, contains, in a concise form, the best of the authenticated sallies and repartees perpetrated by the illustrious interlocutors. After the usual preliminaries, the dialogue proceeded thus:

MADAME DE STAËL. Madame Bonaparte is a charming lady.

BONAPARTE. Any compliment passing through your lips, madame, acquires additional value.

ST. Ah! then you appreciate my opinion and my approbation? But you have doubted my capacity, you have thought me frivolous; nevertheless, my studies in diplomacy, in the history of courts——

BON. I implore Madame de Staël not to drag the Graces to the pillory of politics.

ST. I assure you, General, that your mythological compliment is totally lost upon me: I should prefer that you judge me worthy to talk reason with you.

BON. The right of your sex is to make us lose our reason: do not despise so excellent a privilege.

ST. General, I beg of you not to play with me as with a doll: I desire to be treated as a man.

BON. Then you would like to have me put on petticoats.

ST. TO A GENTLEMAN INTERRUPTING HER.—Sir, be good enough to understand that I desire no assistance, though certainly my adversary is sufficiently powerful to render assistance necessary.

BON. Madame, it was to my aid that he was coming; my danger appalls him, and he was seeking to relieve me.

ST. In any case, I owe him small thanks for his tardy aid, since you confess that my victory seemed certain. He is a true friend, however; he stands by those he likes, even in their absence, when, usually, friendship slumbers.

BON. In that, friendship imitates its cousin—love.

ST. NERVING HERSELF FOR AN EFFORT.—By what means, General, can an ordinary woman, without literary reputation, without superior genius, be sustained in the affection of a man she loves when separated from him by distance or a period of years? Memory, reduced to recalling her charms only, becomes gradually dim, and at last forgets, especially when the lover is a great man. But when the latter has had the good fortune to meet with a strong-minded woman, one worthy of sharing his laurels, and herself enjoying a high reputation, then the distance of time and space disappears, for it is the renown of both which serves as messenger between them, and it is through the hundred mouths of fame that each receives intelligence of the other.

BON. Madame, in what chapter of the work you are about to publish shall we read this brilliant passage?

ST. It has been the constant illusion of my soul.

BON. Ah, I understand; it is your hobby, after the manner of Sterne. So you are seeking the philosopher's stone?

ST. One would think, to hear you talk, that it is impossible to find it.

BON. There are two illusions in this world, though both flow from the same error; that of physical and that of moral alchemy. This idealistic philosophy leads to an abyss.

ST. One, nevertheless, which wit and sagacity may illumine with the rays of genius to its inmost recesses. Do you never build castles in the air, General? Do you never go and dwell in them? Do you never dream, to charm away the monotony of life?

BON. I leave dreams to sleep, and retain reason for my waking hours.

ST. Then you can never be either amused or surprised! You have a scouting party stationed to watch that outpost, the imagination?

BON. Wisdom counsels me to do so, and makes it my duty.

ST. AFTER A MOMENT'S REFLECTION.—General, who, in your opinion, is the greatest of women?

BON. She who bears the most children.[3]

Madame de Staël turned slightly pale at this reply, and said no more. The General rose, bowed, and quitted the room. Both carried away from the interview the elements of mutual dislike and food for a lifelong hostility. "Doubtless," says Lacretelle, "this last question was suggested by the vanity of the inquirer." And Bonaparte, eager to deprive the lady of the tribute she expected in his reply, made answer as we have described. "Certainly," adds Lacretelle, "it was impossible to rebuff a courtesy with greater rudeness and less discernment, for Madame de Staël was one of the powers of the day."[4]

One evening, early in the Consulate, Josephine met Madame de Staël at the house of Madame de Montesson. Bonaparte was to come somewhat later. Josephine, knowing his aversion for her, or fearing her seductions if she were successful in obtaining his attention, received her, as she advanced, in a manner so markedly cold, if not rude, that Madame de Staël recoiled without speaking, and retreated to the extremity of the room, where she dropped into a chair.

She remained for some time apart and alone. The pretty women took a malicious pleasure in the mortification of one of their own

sex, while the gentlemen indulged in impertinent and unmanly remarks. At this moment, a young girl of extreme beauty and light airy step, with blond hair and blue eyes, and dressed entirely in white, left the group that had collected in the vicinity of Josephine, crossed the salon, and sat down by Madame de Staël. The latter, whose heart was as quick as her wit was ready, said to her, "You are as good as you are beautiful, my child."

"In what, pray, madame?" asked the young lady.

"In what?" returned Madame de Staël. "You ask me why I think you as kind as you are fair? Because you crossed this immense and deserted salon to come and sit by me. Upon my word, you are more courageous than I should have been."

"And yet, madame, I am naturally so timid that I should not dare to tell you my fears and trepidation: you would laugh at me, I am sure."

"Laugh at you!" exclaimed Madame de Staël, with moistened eyes and trembling voice; "laugh at you! never! never! I am your sister, henceforth, my dear, dear young friend! Will you tell me your Christian name?"

"Delphine, madame."

"Delphine! What a pretty name! I am very glad of it, for it will suit my purpose exactly. You must know, love, that I am writing a novel; and I mean it to bear your name. You shall be its god-mother; and you will find something in it which will remind you of to-day and of our acquaintance."

Madame de Staël kept her promise, and the passage in the novel of Delphine, in which the heroine, abandoned, is under similar circumstances relieved and sustained by Madame de R., was written in commemoration of this little domestic scene.[5]

Bonaparte soon entered the room, and ignorant of the treatment Madame de Staël had undergone from Josephine, accosted her

graciously, and indeed took evident pains to restrain, during their conversation, his intuitive dislike of the petticoat politician.

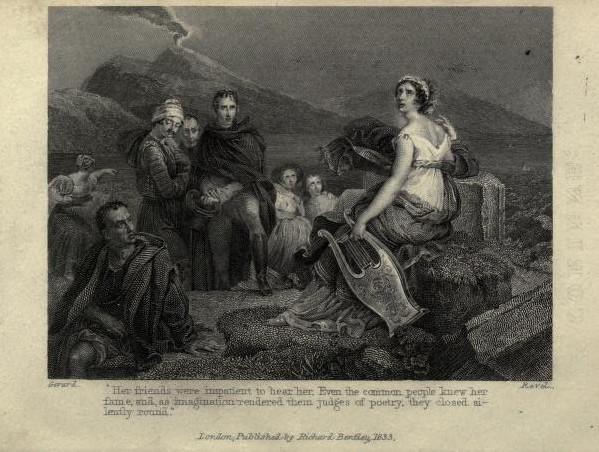

Madame de Staël was now at the apogee of her talent and influence. Her conversation was not what is usually understood by the term. She did not require so much an interlocutor as a listener. Her improvisations were long and sustained pleas, if her object was to convince, or discursive though brilliant harangues, if she sought to display her wealth of thought and of words. Those that were accustomed to her ways rarely answered her, even if, in the heat of argument, she addressed them a question; well aware that it was rather to operate a diversion than to elicit a reply. She required the excitement of an audience, and her eloquence became richer and more rapid as the circle of her listeners widened. She preferred contradiction and dissent to a blind acceptance of her opinions, and the surest method of pleasing her was to adduce arguments that she might refute them, and which might suggest in her mind new trains of ideas. Controversy was her peculiar element, and she sometimes resorted to the charlatanical process of advocating two opposite opinions on the same occasion, in order to show the flexibility of her mind and the pliancy of her logic. In the season of foliage, she invariably carried in her hand a twig of poplar, which, when talking, she would turn and twist between her fingers; the crackling of this, she said, stimulated her brain. During the season when the poplar produces no leaves, she substituted for the twig a piece of rolled paper with which she was forced to be content, till the return of verdure. In winter, her flatterers and admirers always had a supply of these papers prepared, and presented her a quantity, on her arrival at a fête or a conversazione, that she might select her sceptre for the evening.[6] The famous twig of poplar is introduced in Gérard's portrait of Madame de Staël.[7]

She was never handsome, and without the extraordinary depth and brilliancy of her eyes, would have been a plain, if not an ugly woman. Her nose and mouth were homely, and only redeemed by her ever-varying expression. Her complexion was rough, her form

massive rather than graceful, and indicated indolence rather than vivacity. Her hands were beautiful, and ill-natured people asserted that the poplar twig was a mere pretext for keeping them constantly in view. She dressed at all times without taste, and this defect became more conspicuous as she advanced in years, for at the age of forty-five she wore the colors and ornaments which would befit a young lady of twenty. Her coiffure was usually a turban, though this was not the prevailing fashion. Her partisans denied that there was any exaggeration in her toilet, though they allowed that she sought to be picturesque rather than fashionable.

Biography has preserved examples almost innumerable of the readiness of her wit and the profundity of her observation. The love of truth was one of her prominent characteristics. "I saw," she said "that Bonaparte was declining, when he no longer sought for the truth." She held long arguments on equality, and said on one occasion, "I would not refuse the opinion of the lowest of my domestics, if the slightest of my own impressions tended to justify his." Her respect for justice and moderation was evinced in her reply to the remark of a Bourbon after Napoleon's fall, to the effect that Bonaparte had neither talent nor courage: "It is degrading France and Europe too much, sir, to pretend that for fifteen years they have been subject to a simpleton and a poltroon!" She despised affectation, and said that she could not converse with an affected man or woman on account of the constant interruptions of a tedious third person—their unnatural and affected character. Of individuals accustomed to exaggerate, she said: "To put 100 for 10, why, there's no imagination in that." Her faith was sincere and unostentatious, and she would remark, after listening to lofty metaphysical discourses, "Well, I like the Lord's Prayer better than that." One of her best replies was made to Canning, in the Tuileries, after the exile of Napoleon: "Well, Madame de Staël, we have conquered you French, you see!" "If you have, sir, it was because you had the Russians and the whole continent on your side. Give us a tête-àtête, and you will see!"

Madame de Staël's conduct as a wife was not irreproachable. Talleyrand was one of the first, though by no means the last, of her lovers. It was after his rupture with Madame de Staël that he entered upon his liaison with Madame Grandt, and it was this circumstance that led Madame de Staël to ask him the most unfortunate question of her life, for it gave him the opportunity of making the most comprehensive reply of his: "If Madame Grandt and I were to fall into the water, Talleyrand," she inquired, "which of us would you save first?" "Oh, madame," returned the minister, "YOU SWIM SO WELL!" She was revenged on him by drawing— though not very delicately—his character as a diplomatist: "He is so double-faced," she said, "that if you kick him behind, he will smile in front."

Bonaparte, early in the Consulate, sought through his brother Joseph, to attach Madame de Staël to his government; he might have done so, had he cared to conciliate her by expressing, or even feigning, deference to her talents and opinions. But he did not pursue the negotiation, and she continued her political discussions at her house, devoting her days to intrigues, and her evenings to epigrams; until Bonaparte, whose patience was exhausted, and who did not consider his power as yet fully established, directed his minister of police to banish her from Paris. She was ordered not to return within forty leagues of the city. He is said to have remarked, "I leave the whole world open to Madame de Staël, except Paris; that I reserve to myself." It was urged, too, that she had small claims to consideration; she was, though born in France, hardly a Frenchwoman, being the daughter of a Swiss and the wife of a Swede.

During a period of years, Madame de Staël remained under the ban of Bonaparte's displeasure, though, during a short interval, the intercessions of her father obtained permission for her to inhabit the capital. In 1803, she published her "Delphine," a work so immoral in its tendency that it incurred the censure of the critics and the public, and compelled the authoress to put forth a species of apology, which in its turn was considered lame and inconclusive. The character of

Madame de Vernon, in "Delphine," was said to have been intended for Talleyrand, clothed in female garb.

Unable to endure the deprivation of her Parisian friends, Madame de Staël soon established herself at the distance of thirty miles from Paris. Bonaparte was told that her residence was crowded with visitors from the capital. "She affects," he said, "to speak neither of public affairs nor of me; yet it invariably happens that every one comes out of her house less attached to me than when he went in." An order for her departure was soon served upon her, and she set forth upon a pilgrimage through Germany.

In the last week of December, 1807, Napoleon, returning from Italy, stopped at the post-house of Chambéry, in Sardinia, for a fresh relay of horses. He was told that a young man of seventeen years, named Auguste de Staël, desired to speak with him. "What have I to do with these refugees of Geneva?" said Napoleon, tartly. He ordered him to be admitted, however. "Where is your mother?" said Napoleon, opening the conversation. "She is at Vienna, sire." "Ah, she must be satisfied now; she will have fine opportunities for learning German." "Sire, your majesty cannot suppose that my mother can be satisfied anywhere, separated from her friends and driven from her country. If your majesty would condescend to glance at these private letters, written by my mother, you would see, sire, what unhappiness her exile causes her." "Oh, pooh! that's the way with your mother. I do not say she is a bad woman; but her mind is insubordinate and rebellious. She was brought up in the chaos of a falling monarchy, and of a revolution running riot, and it has turned her head. If I were to allow her to return, six months would not pass before I should be obliged to shut her up in Bedlam, or put her under lock and key at the Temple. I should be sorry to do it, for it would make scandal, and injure me in public opinion. Tell your mother my mind is made up. As long as I live, she shall not again set foot in Paris."

"Sire, I am so sure that my mother would conduct herself with propriety that I pray you to grant her a trial, if it be only for six

Welcome to our website – the perfect destination for book lovers and knowledge seekers. We believe that every book holds a new world, offering opportunities for learning, discovery, and personal growth. That’s why we are dedicated to bringing you a diverse collection of books, ranging from classic literature and specialized publications to self-development guides and children's books.

More than just a book-buying platform, we strive to be a bridge connecting you with timeless cultural and intellectual values. With an elegant, user-friendly interface and a smart search system, you can quickly find the books that best suit your interests. Additionally, our special promotions and home delivery services help you save time and fully enjoy the joy of reading.

Join us on a journey of knowledge exploration, passion nurturing, and personal growth every day!