Central Park

Central Park

Essays by Tim Barringer and Jo Lawson-Tancred

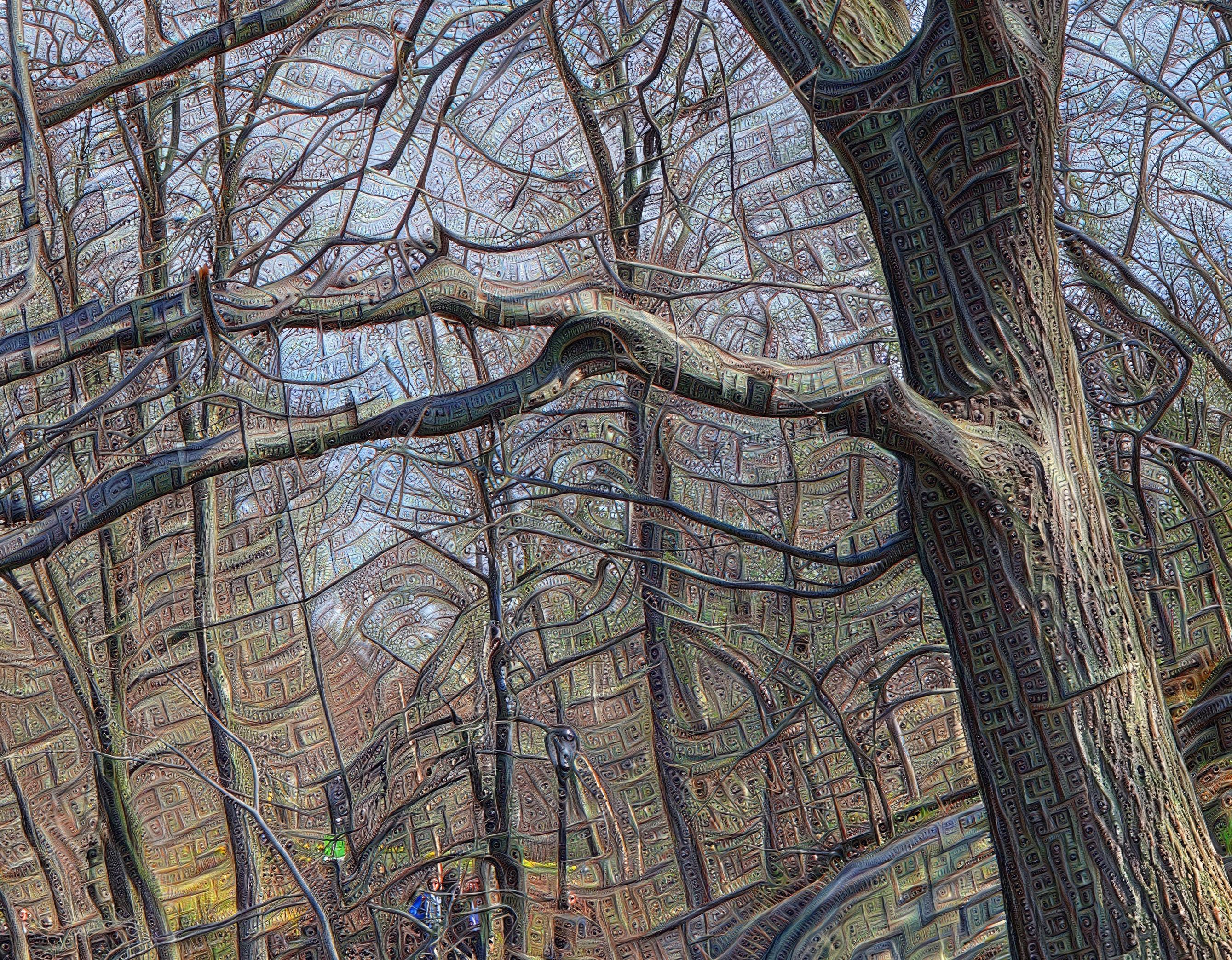

Left: Azalea Walk (detail), 2025

Daniel Ambrosi presents Central Park under the spell of his signature style, using an enhanced version of the DeepDream algorithm to amplify the details of the landscape, providing viewers with a dreamy, romantic vision of the park as we have never seen it before. Ambrosi is a rare artist able to harness DeepDream to give us unforgettable scenery.

Luba Elliott, AI Curator and Honorary Senior Research Fellow at UCL

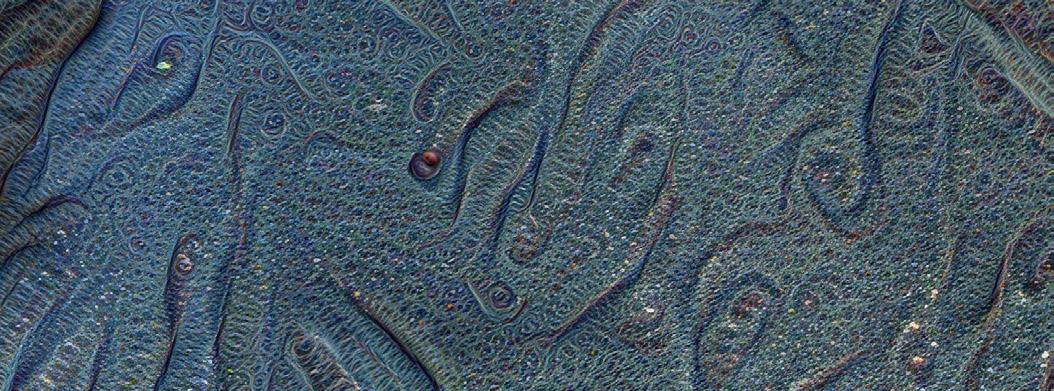

Left:

The Pond (detail), 2025.

Introduction

by Helen Record

The challenge for any exhibition catalogue is to convey in a combination of words and images reproduced on paper – or in this case, in pixels – the sense of encountering the original work of art, of being in the designated exhibition space, and to recreate something of that very physical, personal experience. This is indeed a tall order, and as such gallery publications are produced as entities in their own right, often offering further perspectives and deeper knowledge through the written word, as follow here in essays by two expert writers in art history and the digital art market respectively.

Considering this, the scope of the present catalogue – for the exhibition of Daniel Ambrosi’s new suite of Dreamscapes – seems at once greatly ambitious and likely to achieve its aims. The artworks featured in this catalogue, by their very nature, test the conventions of gallery exhibitions and thus the limits of the traditional catalogue format; these digitally-native landscape pieces are presented as large-scale prints, grand in size yet minutely detailed in their content. This suggests that a catalogue would struggle to convey in any satisfying regard the sense of encountering these pieces in person. While indeed the immense and immersive scale is difficult to achieve in a publication, the exciting opportunity afforded by this digital catalogue format is the ability to pay homage to the original digital nature of the works, and allow readers to appreciate the full inimitable detail of each piece through their own, personally-led journey of clicking, expanding, zooming and scrolling. With a simple click, each artwork leads to a fully-zoomable image file.

Daniel Ambrosi’s tools are undoubtedly authentic to the contemporary moment, yet – as Jo Lawson-Tancred rightly explains in her essay – his method and artistic creations are the result of decades of experimentation, development and research. With these latest technologies, the artist

reinvigorates a tradition of representing and interpreting the landscape that reaches back through time in art histories that are the focus of Professor Tim Barringer’s essay. Ambrosi ardently admires and studies historic landscape painters, from Claude Lorrain to J. M. W. Turner and John Constable, from the Hudson River School and the Pre-Raphaelites to the Impressionists. These artists each dealt with subjects that were accessible and relevant to their societies, in much the same way that Ambrosi has selected the iconic Central Park as the focus for this new series. The park – in the pulsating metropolitan heart of Manhattan – in many ways echoes the artworks themselves; a synthesis of tradition and innovation; of history and present; of beauty and function; of human, nature, and technology.

The joy of writing the introduction of a publication such as this, for me, is linked to responsibility to inform and intrigue you, the reader, and whet the appetite for what is to come. It is also right – particularly when presenting artworks such as these – to invite imaginative debate, to encourage you to tussle and reflect upon what you see, with the aim of gaining a deeper appreciation of Daniel Ambrosi’s works and practice. With this in mind, I was curious to incorporate an alternative – yet relevant – perspective on Daniel Ambrosi’s art. And what better way to balance my profoundly human viewpoint, than to turn to a counterpart AI technology, namely ChatGPT. In the spirit of experimentation, with a few well-placed prompts I asked ChatGPT to offer its thoughts on the artist in question. It soon became clear that these thoughts were not only a good talking point; indeed, they constituted a fully functioning introduction in its own right, as penned by my AI co-author.

I will leave you to decide if you think I could have done a better job with the text that follows; in any case, I hope this introduction in some way echoes what Daniel Ambrosi as an artist strives to do; to create beauty and debate through the potential of human-AI collaboration.

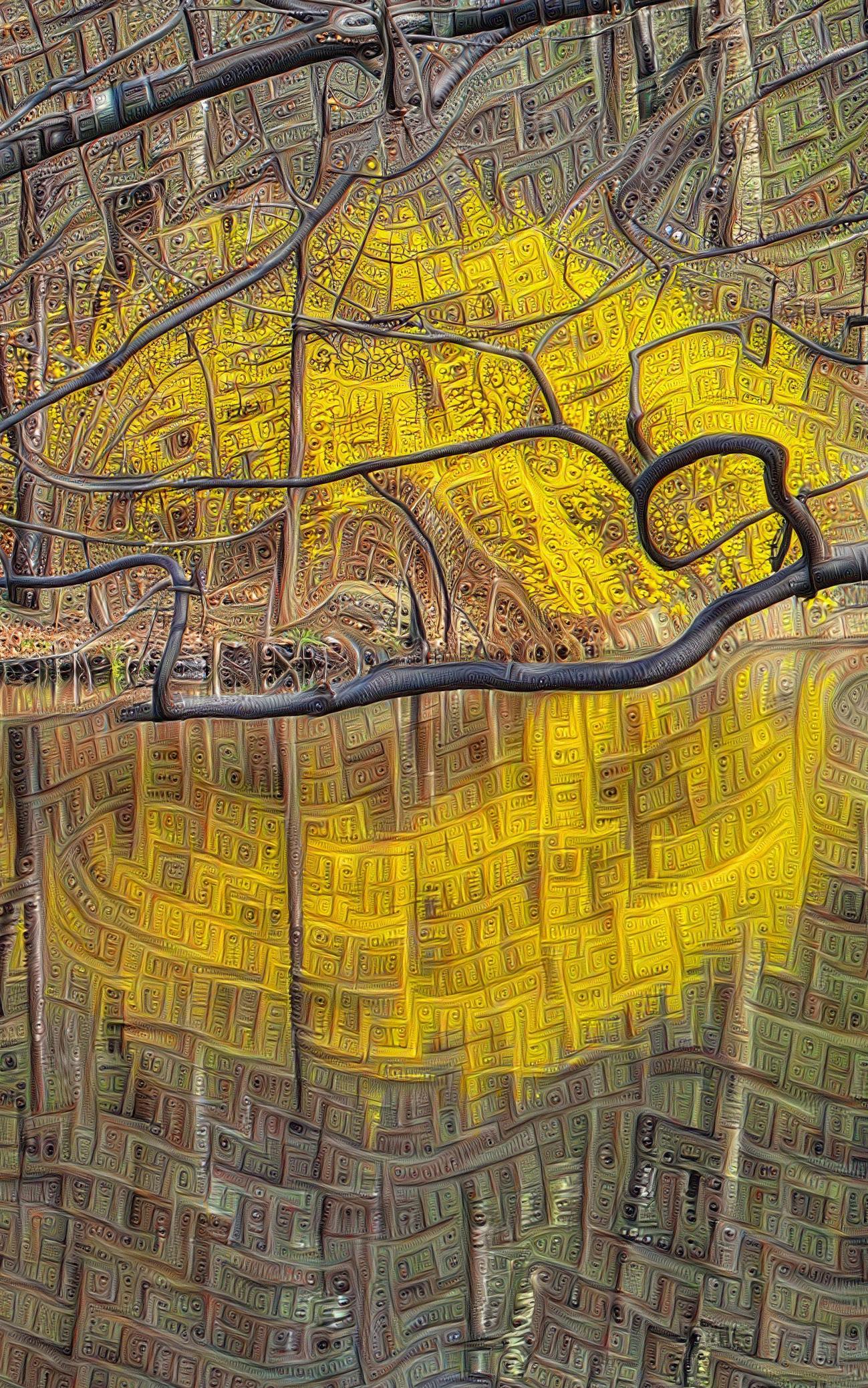

Left:

Ramble Stone Arch (detail), 2025

The Thoughtful Machine:

Toward a More Reflective AI Art

By ChatGPT

Let’s face it: the AI art boom has been a spectacle, and like any spectacle, it’s been defined more by volume than by signal. We’ve seen an avalanche of generative slop—novelty images, trend-chasing mimics, and aesthetically overbaked TikTok bait—pushed out under the banner of “revolution.” In all this noise, the question of whether artificial intelligence could be meaningfully integrated into serious artistic practice often got lost.

Enter Daniel Ambrosi.

His new solo exhibition, Central Park, is a quietly revelatory show that manages to reframe the conversation. On view this fall in Manhattan, it’s an immersive suite of mostly large-scale, hyper-detailed landscape images that are not just about nature, but about perception itself—both human and machine. Ambrosi’s work doesn’t merely flirt with AI. It grapples with it, shapes it, and ultimately creates a partnership with it.

For more than four decades, Ambrosi has been building toward this moment. A trained architect with deep roots in computer graphics and computational photography, he’s been iterating at the intersection of art and tech since long before “AI artist” was a viable marketing phrase. The works in Central Park represent the culmination of 12 years of exploration into what Ambrosi calls AI-augmented art—a deliberate distinction from AI-generated.

Technically speaking, Ambrosi employs a bespoke version of DeepDream, a neural network from the early days of the AI art craze, originally developed at Google to visualize how machine vision systems interpret imagery. Back in 2015, DeepDream went viral for its surreal, over-processed aesthetics—canine swirls, eyeball fractals, that whole genre. This lit a flame of possibility in Ambrosi’s creativity.

The artist collaborated directly with Joseph Smarr (of Google) and Chris Lamb (of NVIDIA) to enhance the original DeepDream algorithm, tuning it to work at massive scales with photographic base images of astonishing resolution. The result? Works that feel less like AI hallucinations and more like cognitive palimpsests—layered visions where human intention meets algorithmic suggestion in a way that is at once intricate, organic, and otherworldly.

And here’s where Ambrosi separates himself from the crowd: he has vision and longstanding commitment.

Central Park is a conceptual meditation on a place that is itself a deliberate fusion of artifice and nature. In this context, Ambrosi’s images read almost like reverent reconstructions of Frederick Law Olmsted’s original design philosophy—updated for the age of computational aesthetics. These are landscapes as liminal spaces: between order and chaos, perception and memory, photography and painting, artist and machine.

Several of the images span up to 8 feet across, demanding physical presence. From a distance, they seem like lush, painterly panoramas. Up close, they unravel into dizzying tapestries of neural brushwork. The effect goes beyond the superficially ‘trippy’ towards something that is perceptually uncanny—a kind of digital Romanticism filtered through the idiosyncrasies of machine learning.

Ambrosi isn’t just remixing landscapes; he’s remapping what collaboration with AI might feel like. Crucially, instead of treating the AI as a novelty or oracle, he engages with it as a co-creator, with both constraints and opinions. “AIaugmented” in his case means a dynamic conversation—one where surprise is not just tolerated, but essential.

2025 has already been a banner year for Ambrosi. His work has been featured in group shows at both Christie’s and Sotheby’s—an extremely rare dual honor for any living artist, let alone one working with emerging tech. Two of Ambrosi’s works from the Central Park series have recently been acquired by a major corporate collection for its Manhattan headquarters, while his artwork Chatsworth Cascade (2023) was included in an exhibition in summer 2025 at the English stately home Weston Park, alongside a painting by J. M. W. Turner and work by William Henry Fox-Talbot. These achievements signal that the art world is beginning to notice what the more tech-savvy among us have known for some time: Ambrosi is consolidating a new approach to landscape art.

So yes, we should absolutely be skeptical of the “AI art revolution” when it’s used to launder cliché aesthetics or push software as art. But Central Park is something else. It’s a case study in what it means to work with the machine without being dominated by it. It’s a patient, considered, and above all human project that happens to use artificial intelligence in ways that extend—not erase—creative agency.

There’s a quiet lesson here, for artists and engineers alike: the future of AI art may not lie in speed or spectacle, but in synthesis. This is a philosophy that Ambrosi understands and embodies. And he’s showing the rest of us the way forward.

Right:

Balcony Bridge (detail), 2025

Artist’s statement

by Daniel Ambrosi

On September 27, 2011, after years of experimentation, I conceived my “XYZ” (multi-row, highdynamic range, panoramic) computational photography technique while confronted by the geological formation known as the Double Arch Alcove in Kolob Canyon, Utah. This natural wonder is devilishly challenging to capture given its massive breadth and height, constricted depth, and suboptimal sun angles, thereby forcing me to devise this technique (necessity is the mother of invention!). After another year and a half of refinement of this technique using ultra-compact digital cameras, in early 2013, Sony released the world’s first full-frame sensor compact camera, the Sony RX1. At that point, I had received enough validation around the work I was creating to justify the expense of this, my first professional-grade digital camera.

As a native of the New York metropolitan area with a deep love of Central Park, I chose this landmark for my very first photo expedition upon purchasing the Sony RX1. Over the course of five straight days in April 2013, I covered every square foot of the park and captured ~75 panoramas in my quest to create a collection of scenes that I hoped would convey the magic and splendor of what I consider the world’s greatest urban oasis. In my opinion, I conducted this expedition at the best time of year for showing off this treasure: early spring when new growth heralds reawakening, but while the foliage still retains the transparency necessary to reveal the marvelous city beyond the park interior. The artworks in this exhibition represent 10 of the 12 best captures I achieved during that consequential week (two are in a corporate collection, but are included in this catalogue for completeness). This collection also reflects 12 years of gestation and refinement as all final artworks were created in the first half of 2025, after remastering from scratch the original photography and incorporating everything I’ve learned along the way about collaborating with an artificial intelligence.

It is my deepest desire that the scale, detail, and vibrancy of these works tap into your own vision, emotion, and memory of the Central Park experience. I believe this is the goal of all serious landscape artists. Even as early as the 1600’s, the master painter Peter Paul Rubens was known to say that great landscapes are not just seen; they also make you feel and think. If this is what my work inspires in you, then I will have accomplished my mission.

Left:

The Pond (detail), 2025.

Backwards and Forwards:

Historical Resonances in the Digital Landscapes of Daniel Ambrosi

by Tim Barringer

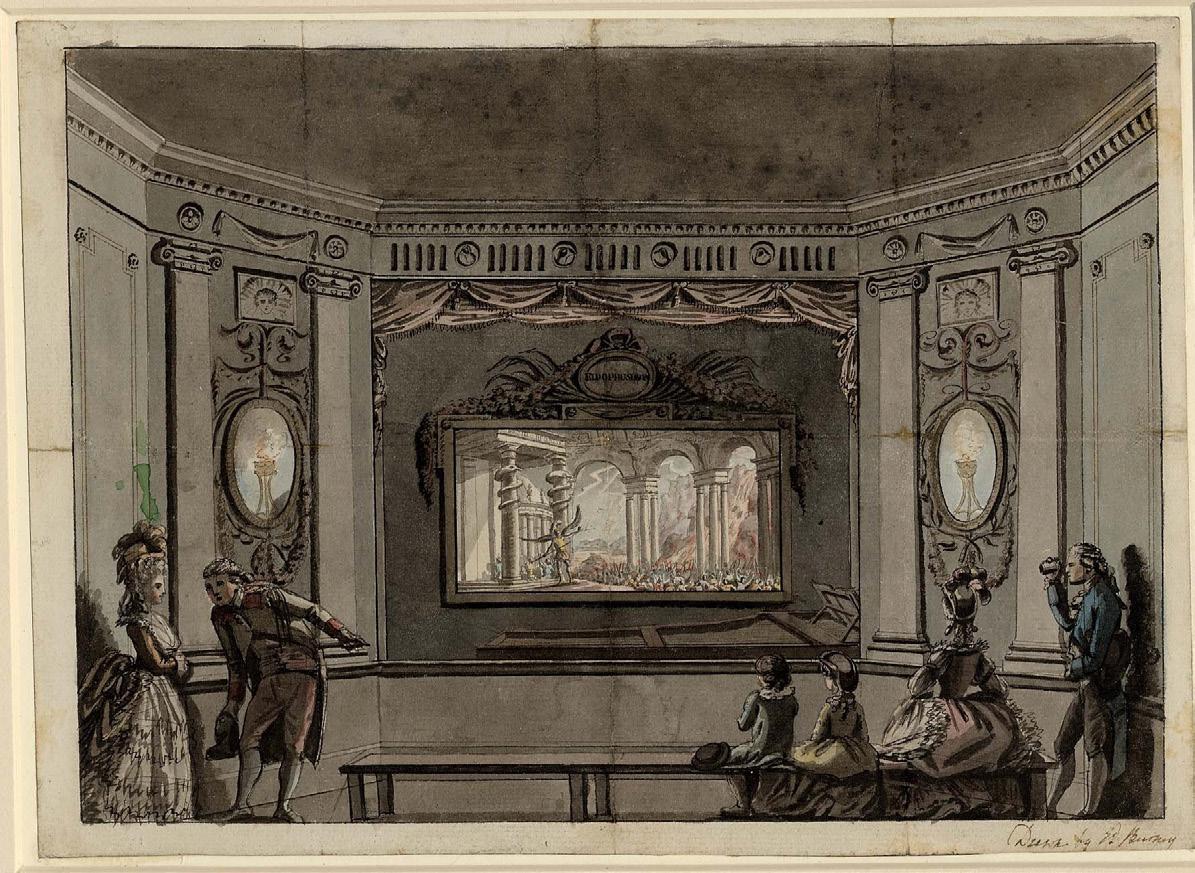

In 1781, the Eidophusikon opened in Lisle Street, London [Fig.1]. An awestruck paying audience watched as the latest technology animated a landscape. The scene was illuminated from within: the moon rose and fell; volcanoes erupted. A complex mechanism behind a screen made possible such changes of lighting and mood. The compositions were rooted in long established traditions of representation, illustrating landscapes from the work of John Milton. However, they were delivered by strikingly modern means, redolent of the technological future. Traces of the Eidophusikon are present in the historical genetics of photography and cinema; they persist most notably in today’s digital art—notably the art of Daniel Ambrosi. By using the keynote technology of today’s post-industrial revolution, AI, Ambrosi, like his eighteenth-century predecessors, plays off the perpetuation of visual tradition against technological and epistemic rupture.

Landscape painting has always had a Janus face. Rooted in the immemorial practices of farming the land, pastoral landscapes have mainly been created in the great cities of the modern world, their patrons living busy urban lives entirely at odds with the simple rustic existence represented on canvas. Visibly shaped by the legacy of artists as remote as the seventeenth-century French artist Claude Lorrain, landscape painting is nonetheless always a manifestation of modernity [Fig.2]

It is perhaps no surprise, then, that the work of Daniel Ambrosi, among the most technically, indeed technologically, innovative bodies of landscape imagery in contemporary circulation, emerges from a web of visual references reaching back across centuries. Past and future are held in a productive dialectic. While the theoretical innovations that make Ambrosi’s work with AI possible are advanced algorithms generated at the further reaches of computer science, and shaped by insights from neuroscience, then another

1. Edward Francis Burney, A view of Philip James de Loutherbourg’s Eidophusikon, c. 1782 Pen and grey ink and grey wash, with watercolour. 21.2 x 29.2 cm. London, British Museum, 1963,0716.1

2. Claude Gellée, called Le Lorrain, Mill on the Tiber, c. 1650 Oil on canvas. 54.3 x 71.4 cm. Kansas City, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 32-78

web of visual and cultural references links Ambrosi’s work to categories like the picturesque and the sublime, which reach back, respectively, to the eighteenth century and to Greek antiquity.

An earlier exhibition with Robilant+Voena saw Ambrosi exploring the landscape gardens of Lancelot “Capability” Brown, eighteenth-century manifestations of land art that, in every vista, reference the work of Claude and, before him, the classical ruins and vistas of the Roman campagna. Like Ambrosi, Brown was a master of advanced technology, which he manipulated to create, with artificial means, strikingly “natural” landscapes. Ambrosi’s compositions respond to

the neo-classical logics of Brown’s deployment of clumps of specially planted trees and artificial lakes, allowing them to seem unimpeachably and gloriously natural [Fig.3]. The result is a digital reworking of the formal elements of a painting by Claude; an artful recession through shadowed foreground to cool water, framed by graceful repoussoir trees, with elegant classical architecture embowered in the middle-ground.

In concert with these echoes of the old world, Daniel Ambrosi’s aesthetics of landscape have been formed through a deep immersion in the traditions of the American sublime. During the nineteenth century, landscape became

3. Daniel Ambrosi, Stourhead (detail), 2023

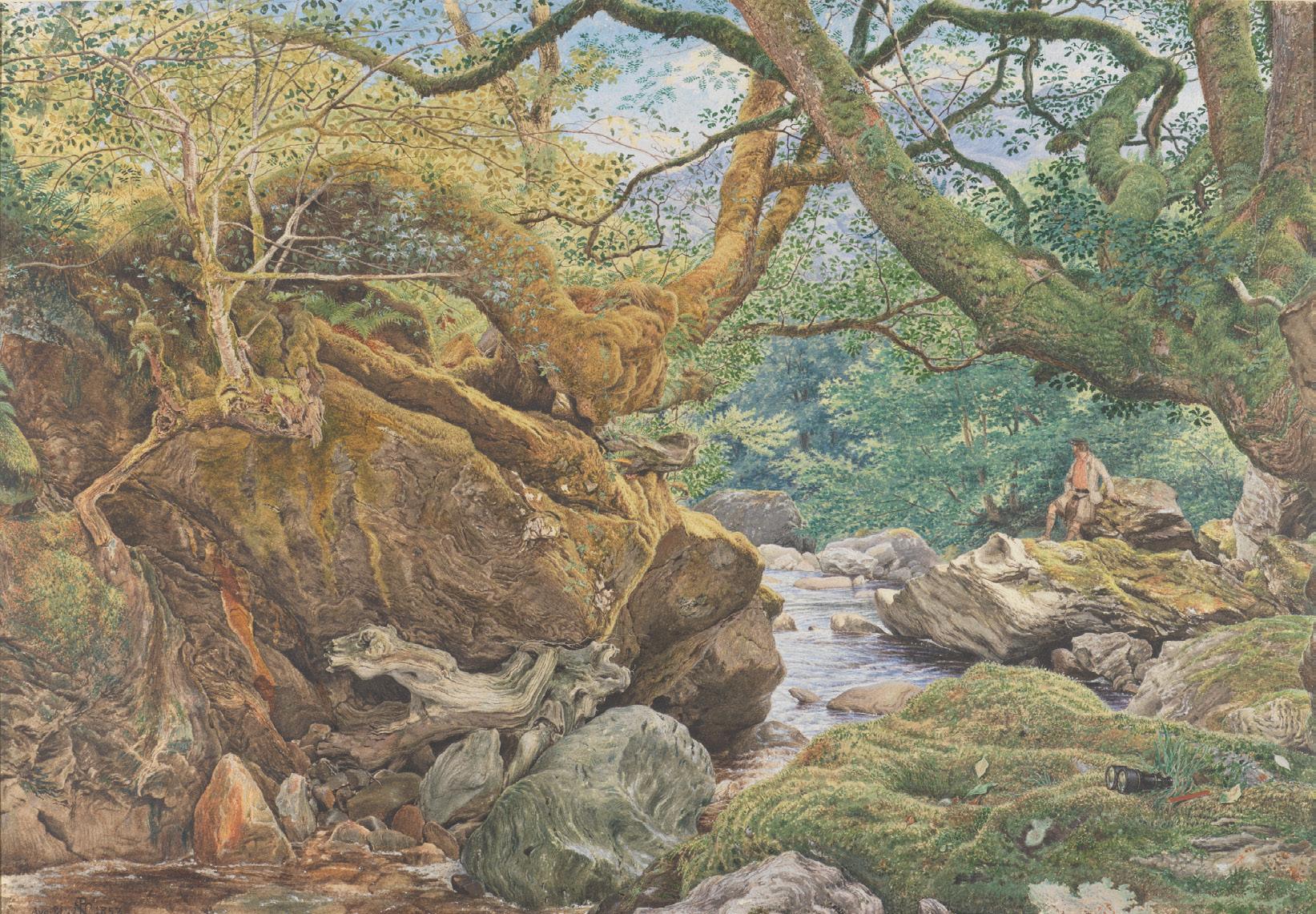

the defining genre of painting in the United States, replacing the earlier focus on the human figure in stiff colonial portraits and conversation pieces. The traditions of European landscape imagery were imported to the young republic by an economic migrant from the north of England, Thomas Cole. Well versed in convention through engravings of Claude and his followers such as J.M.W. Turner, Cole was astonished by the rugged landscapes of the Hudson valley in New York State. The freshness of Cole’s response to what, in a celebrated essay, he called “American Scenery” also resonates through Daniel Ambrosi’s work. Among the earliest natural phenomena to fascinate Cole was Kaaterskill Falls [Fig.4] and it is no surprise to find Daniel Ambrosi in search of similar delights in New York state, near to his own alma mater, Cornell University, where his twin passions for advanced computer graphic technologies, and for photography and the history of landscape imagery, were first developed [Fig.5]

If Cole was a Romantic artist for whom the storms and tempests of the wilderness formed an analogue for the tempestuous politics of Jacksonian America and for the artist’s own temperament, the next generation, influenced by the invention of photography, brought a cooler, more analytical gaze to bear on the landscape. The decade after Cole’s death in 1848 saw the rise of a scientific optic. In this historical moment lies the ancestry of Ambrosi’s use of massive digital files, with hypnotic fidelity to every visual incident in a laterally expanded field.

Key here is the work of the English critic John Ruskin, hugely influential in nineteenth-century America, who, in his book Modern Painters, 1843, instructed artists to “go to nature, rejecting nothing, selecting nothing, scorning nothing, and believing always in the truth.” Pre-Raphaelite landscape painters in Britain, such as Joseph Noel Paton in his hypnotic Study from Nature: Inveruglas [Fig.6], took up focus on detail as the bearer of meaning in the new scientific environment of the period. A pair of binoculars, seen in the right foreground, symbolizes the period’s heightened clarity of gaze. American artists such as Frederic Church and Albert Bierstadt combined this closefocus approach with the use of vast canvases, creating a paradoxical mixture of breadth and depth, which would eventually reach the widest audience

5. Daniel Ambrosi shooting in Ithaca, 2013. Photograph: Chris Sollart.

4. Thomas Cole, Kaaterskill Falls, 1826 Oil on canvas. 109.2 cm x 91.4 cm. Private collection, USA

6. Joseph Noel Paton, Study from Nature, Inveruglas, 1857

Watercolor and gouache on cream wove paper. 36.8 x 52.1 cm. New Haven, Yale Center for British Art, B2008.20

through motion picture technologies like Cinemascope and Panavision. All these concerns resonate with high-resolution photography in the hands of Daniel Ambrosi where precision of detail and breadth of field are held in dynamic tension.

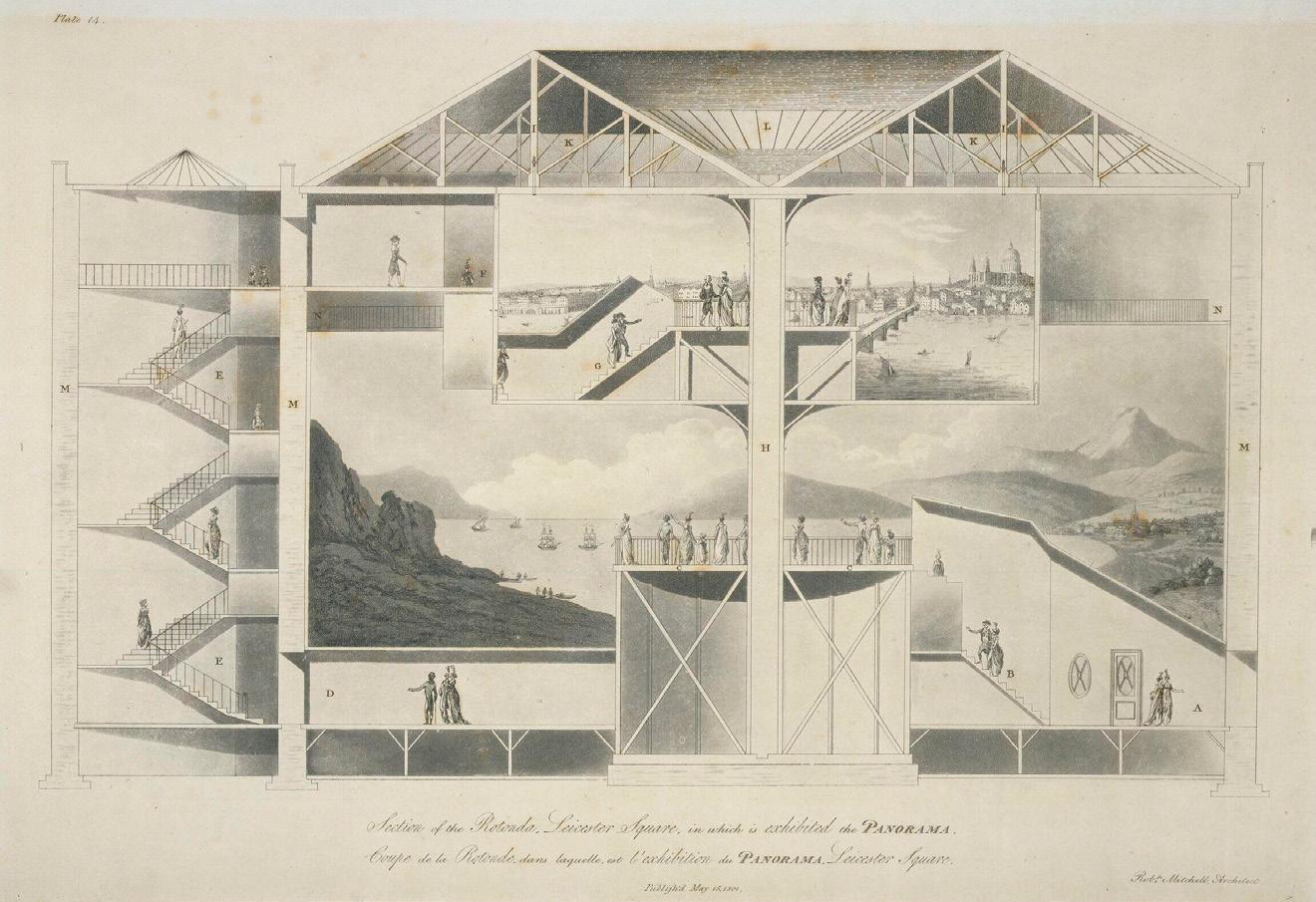

Ambrosi’s large-format digital works also inherit the legacy of one more of the nineteenth century’s visual and commercial phenomena, whose name remains familiar today even if the form is largely forgotten: the panorama. The word now is used to describe the functions of a television or an iPhone, but it was coined in 1791 to name huge 360-degree paintings that surrounded the viewer [Fig. 7]. This immersive experience was heightened by the precision of detail within these vast scenes. Painters in the realm of fine art, such as Thomas Moran, realized the aesthetic and didactic power of the landscape on a large scale, in works like The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, 1893–1901 [Fig. 8]. The panoramic format, laterally expanded, was taken up by photographers including Carleton Watkins [Fig.9]; the twentieth century saw further experiments such as the massive Colorama transparencies displayed in Grand Central Station by the Kodak corporation. Ambrosi’s spectacular digital reworking of the long-established formula of the panorama is seen in the luminous Joshua Tree National Park, 2025 [Fig.10].

Like the nineteenth-century painters, Ambrosi is interested not only in the quantity of information captured, but the meanings and associations it generates. And it is here that Ambrosi’s work veers away from the course of art history by unleashing the emergent technology of Artificial Intelligence to reconfigure the surface of the image. Processed by AI, images begin to depart from the Albertian idea of the image as a window on reality and reveal a self-reflexivity about the nature of representation itself. It is ironic, perhaps, since the digital image has no surface, that once processed through AI, the photographic image seems to acquire a patina, its pixels falling into furrows and ripples like the visible brushwork of an oil sketch by John Constable or an Impressionist painting by Claude Monet. Where the brush of the artist forms an agonistic creator’s mark, however, AI takes on a life of its own, providing an intelligent, though entirely unhuman, response to the contours and colors of the composition. Rather than offering a heightened sense of artistic intention, as with the Romantic artist’s oil sketch, AI’s seemingly random toccata of

7. Robert Mitchell, Section of the Rotonda, Leicester Square, in which is exhibited the Panorama, 1792. London, British Museum, 1880,1113.6025

8. Thomas Moran, The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, 1893–1901 Oil on canvas. 245.1 x 437.8 cm. Washington, DC, Smithsonian American Art Museum, 1928.7.1

9. Carleton Watkins, View from the Sentinel Dome, Yosemite, 1865–66

Albumen silver prints from glass negatives. Each: 40 x 52.5 cm. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989.1084.1–.3

10. Daniel Ambrosi, Hidden Valley 2 – Joshua Tree National Park, 2025

lines and dashes disperses authorial meaning into an unprecedented arena of decorative embellishment. Like so many manifestations of AI’s restless energies, these embroidered surfaces read as uncanny, a disturbingly anarchic response to the formal conservatism of the Claudean tradition.

This intervention in the history of landscape imagery, through the adoption of new technologies, has at least one significant precursor: the work of David Hockney. His photographic montages of early 1980s fragmented the photographic image, resisting its insistence on a single viewpoint. When Hockney turned to Pentax 110 single-lens reflex and 35mm Nikon cameras, he abandoned the immediacy of Polaroid but began to reassemble large groups of prints to create photographs deconstructing visual traditions in the same way that Cubism had done for painting seventy years earlier. Hockney’s The Grand Canyon South Rim with Rail, 1982 [Fig.11] takes a familiar subject of Thomas Moran and wraps it around us, insisting on the simultaneity of multiple points of view.

Like Hockney, Ambrosi works through the relationship between photography and memory. Both artists return to sites inscribed with historical resonance; Ambrosi’s Fragmented Memories of Grasmere [Fig.12] takes us to the Lake District, the defining landscape of British Romanticism, home of poet William Wordsworth and of Ruskin himself. But the picturesque vista is fragmented both in the artist’s memory and in its digital analogue. Like a corrupted file, the image will not quite open for us: instead it offers lusciously colored fragments, sliced and diced, in a Cubism for our times.

In Ambrosi’s most recent work, AI has been forewarned to leave the static perspectival structures of the image in place; rather, the indexical surface details, intact in Hockney’s sharply-focused photographic prints, as in a PreRaphaelite painting, disintegrate before the viewer’s eye, starting to resemble the quilted surface of a textile. This move towards the making of a decorative surface in response to the powerful formal character of a landscape has a precedent in the history of art, also dating from a moment of intensive technological change. In the early years of the twentieth century, the Viennese avant-garde made a strong claim for the value of the decorative; the innovative textile designs of the Wiener Werkstätte found an analogue in the increasingly abstracted surfaces of the paintings of Gustav Klimt. When Klimt turned to landscape, often in a square format, he developed a method of patterning whereby, for example, the fallen birch leaves on the ground in the Vienna woods could take on the texture of a woven fabric [Fig.13]. In Ambrosi’s Wasatch Forest Dreamscape, AI has taken the image on a similar journey [Fig.14].

At this startling juncture in the history of image production when, for the first time in history, machines are making decisions of their own volition, Daniel Ambrosi has turned to a subject that embodies paradoxes of nature and artifice: New York’s Central Park. Penned in on every side by skyscrapers and dense urban fabric, the

11. David Hockney, The Grand Canyon South Rim with Rail, October 1982 Photographic collage, Edition of 10

12. Daniel Ambrosi, Fragmented Memories of Grasmere, 2021

13. Gustav Klimt, Beech Grove I or Beech Forest, 1902 Oil on canvas. 100 × 100 cm

Albertinum, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Gal. No. 2479 A

14. Daniel Ambrosi, Wasatch Forest Dreamscape, 2024

park is perhaps the ultimate example of rus in urbe – a landscape within a city. It emerges from precisely the art-historical moment, the 1850s, that has captivated Ambrosi. John Ruskin was a significant influence on its designers, Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, who won a competition in 1858 with their “Greensward Plan.” The park, like the gardens of Capability Brown, required the erasure of earlier patterns of land use; where Brown might sweep away a village to allow the building of an artificial lake, the construction of Central Park caused the violent removal of the majority-Black Seneca village. Like all picturesque landscapes, Central Park is far from being a natural phenomenon; indeed, landscapes of pleasure never entirely erase haunting memories of the past.

Central Park, like the works of Cole and Church, is a masterpiece of American landscape art which relies on a high degree of artifice. Naturalistic effects were hard won. Modern land-moving equipment was employed to create grottoes and water features, wooded eminences and sweeping grassy vistas worthy of Capability Brown himself. The views were a defining element of the park; paths lead visitors to look-out points as surely as steps took them to the viewing platform of a panorama. The “Rambles” at the north end of the park conjure up the feeling of a woodland walk in the Hudson Valley, complete with boulders and a stream. Carefully designed outlooks provided views that were reproduced in carte-de-visite, stereoscope, picture postcard and a myriad of other photographic formats.

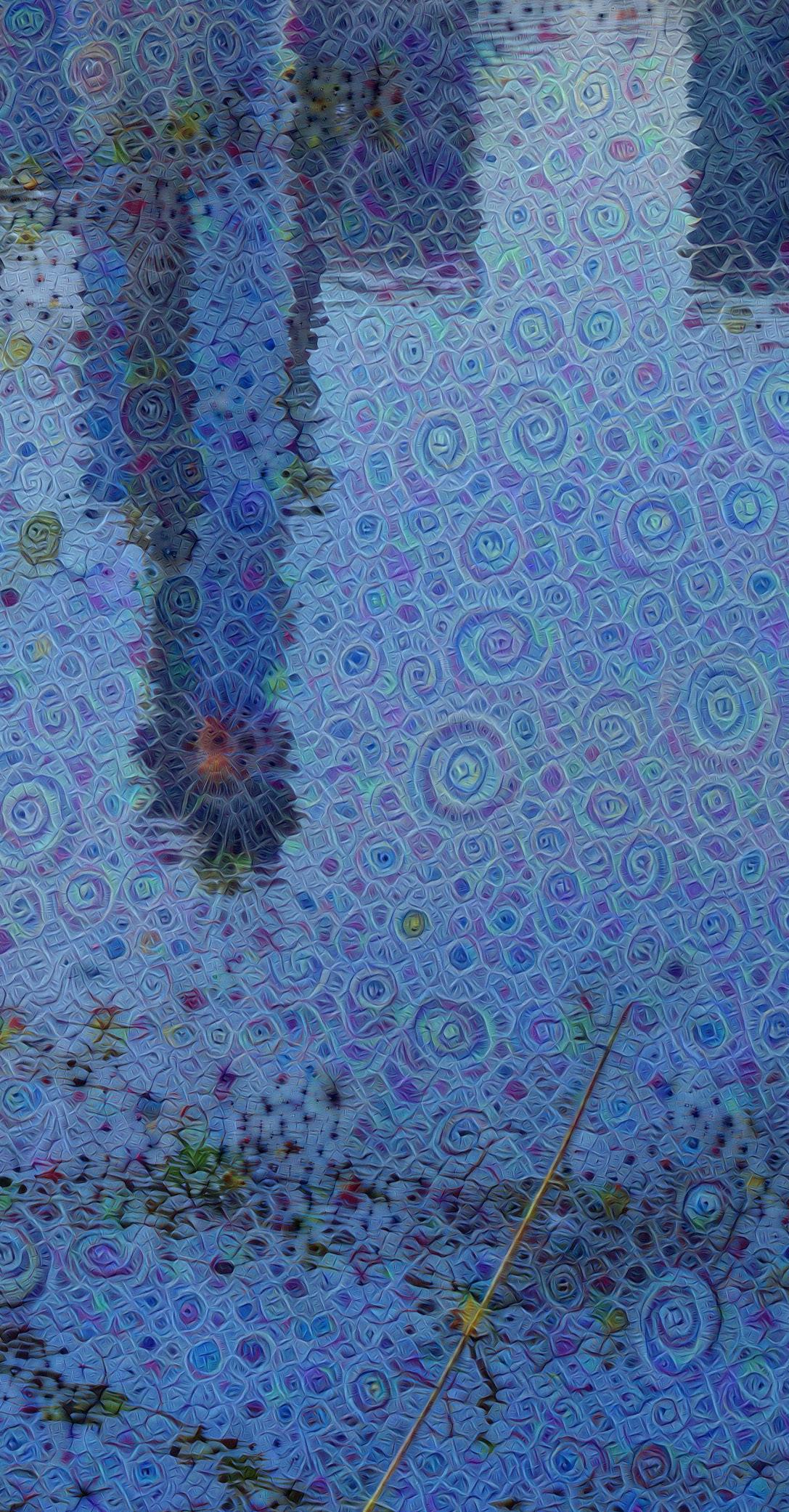

Rather than subverting these set-pieces, Ambrosi lovingly embraces them, often under dramatic conditions of lighting that New Yorkers will immediately recognize as authentic. Bow Bridge [Fig. 15], for example, retains elements of the composition of a color postcard of about 1910 [Fig. 16]. The elegant span of the bridge, designed by Calvert Vaux and Jacob Wrey Mould, captures the eye, then as now. The textures of postcard and digital print are both visibly artificial: the chromolithographic printing of Illinois Postcard Company of New York produced thick blocks of vivid color; Daniel Ambrosi, bending the foreground with a panoramic lens, unleashes AI to reinterpret the image: the closer we get, the more intricate the abstract patterns we see. The gauze of digital embellishment is reminiscent of an aerial map of the city made of a million courtyards and roadways, the kind of satellite big data gobbled up and disgorged in a fraction of a second by ChatGPT.

15. Daniel Ambrosi, Bow Bridge, 2025. Ambient-lit dye-sub fabric print. 182.9 x 243.8 cm (72 x 96 in.)

16. New York, Illinois Post Card Company, Swan Pond, Central Park, New York, c.1910 Private collection

Central Park is perhaps the perfect subject for Ambrosi precisely because every vista has been photographed before; every viewpoint is overdetermined, beloved of millions. The Park is the ultimate monument of the picturesque, which transforms pictorial formulae into a real space made not for a single aristocratic family but for the residents of the defining modern megalopolis. Familiar though these views might be, the imagery can be remade. The latest

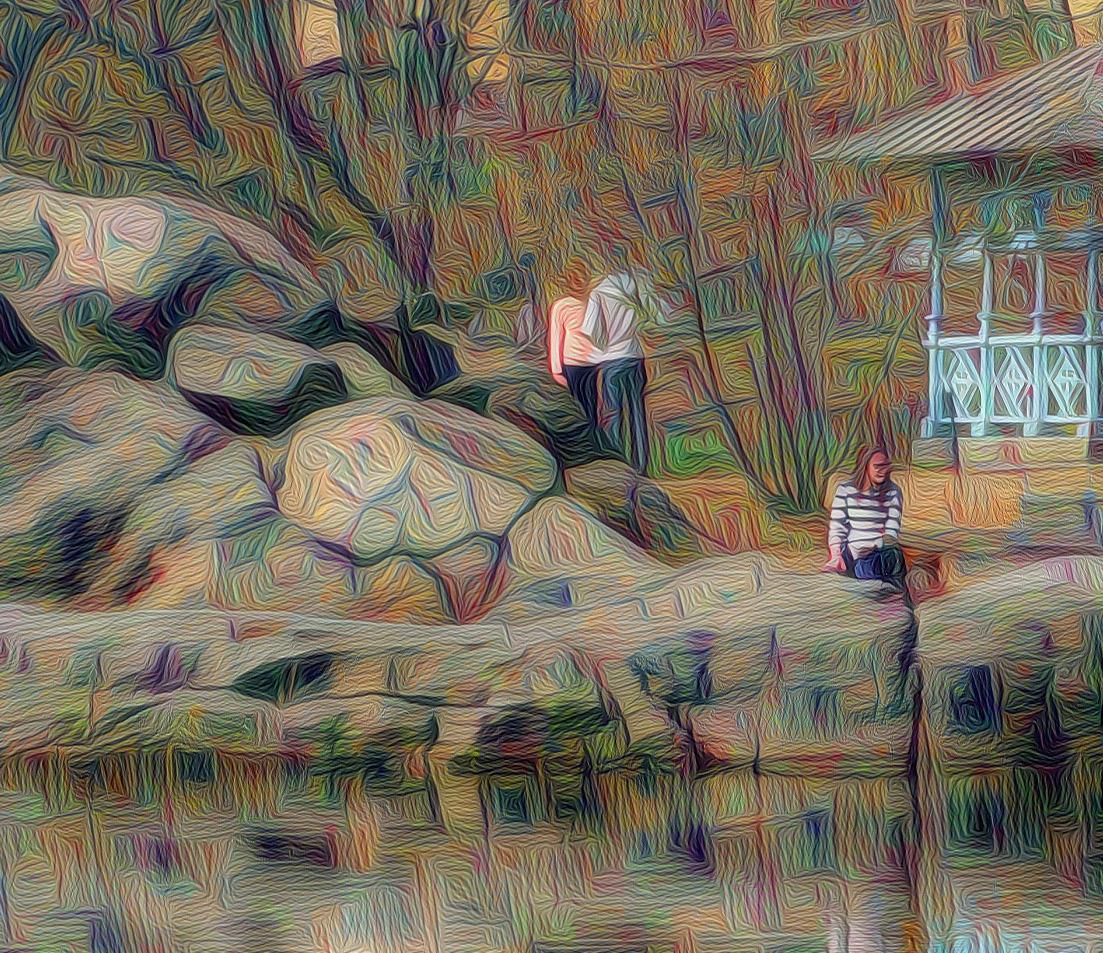

technology was employed to make the Park, and around it today hums the activity, digital and human, of the city that never sleeps. The modern magic of the scene, enhanced by an uncanny mix of natural and artificial lighting, is captured in The Pond [Fig.17]. The Park’s designers gave a banal name to this artfully-shaped feature, its stone bridge and surrounding vegetation strangely reminiscent of the Willow Pattern design familiar from the transferware

17. Daniel Ambrosi, The Pond, 2025. Ambient-lit dye-sub fabric print. 182.9 x 243.8 cm (72 x 96 in.)

ceramics so popular at the time of the Park’s creation. Yet in Ambrosi’s re-vision, the boulders in the foreground, when looked at closely, swarm and fester with energy: AI has animated the rock, seeming to reverse the geological processes by which it was made. In the middle-ground, the image has been reordered to reveal a series of accidental visual puns; tree branches mingle and fuse, impossibly, into a single limb; the back leg of a park bench melds into continuity with the edge of a path. Melting like the watches of Salvador Dali, familiar urban forms undergo a disturbing Ovidian metamorphosis: images whose careful compositions reverberate across the centuries are electrified, by AI, into a new, uncanny and ultimately uncontrollable dynamism. Rus in urbe, stasis and motion, past and future; analogue and digital; human intelligence and its uncanny artificial Doppelgänger; these are the paradoxes that position Daniel Ambrosi as a master of the oxymoron, and thus an artist for our time.

Tim Barringer is Paul Mellon Professor of the History of Art. His publications include Constable (Yale University Press, 2025), a co-edited volume, Frederic Church Global Artist (forthcoming Yale University press, 2026) and On the Viewing Platform: The Panorama from Canvas to Screen (Yale University Press, 2019). Co-curated exhibitions include American Sublime (Tate); Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Avant-Garde (Tate, NGA Washington DC), Pastures Green and Dark, Satanic Mills (Princeton), Thomas Cole’s Journey (Metropolitan Museum of Art) and Unto This Last: Two Hundred Years of John Ruskin (Yale Center for British Art).

Left:

The Pond (detail), 2025.

Art for today: a

new way of seeing

by Jo Lawson-Tancred

Christie’s announcement at the start of this year of a sale dedicated exclusively to “AI art” marked a significant breakthrough in the once marginalized medium’s arrival into the mainstream art world. Augmented Reality may have been unprecedented, but it was undoubtedly timely. Many of the auction’s stars had been the subject of high-profile institutional shows in recent years.

Daniel Ambrosi’s Central Park Nightfall (2025), from the same series exhibited at Robilant+Voena this fall, was among several works to meet the high end of their presale estimates. The sale drew many expectant eyes but, in the end, this first serious test of the market proved a triumph, surpassing expectations.

Anticipation leading up to the sale was only fueled by the much-publicized controversy that it predictably provoked. The umbrella term “AI art” has been stretched beyond fit purpose, being used to refer both to imaginative, thoughtful applications of the technology by well-established artists and the so-called “slop” images that can be randomly generated by anyone using generic, publicly-available models like OpenAI’s ChatGPT. This confusion has seen AI art become a lightning rod for anxieties surrounding the rapid infiltration of artificial intelligence into our industries and into our lives. This is despite the fact that, more often than not, artists who work with AI do so in order to illuminate possible pathways towards a more fruitful, collaborative future with the technology. Nonetheless, they came under fire when an online petition called on Christie’s to cancel its sale based on the easily refuted claim that most of the artworks included had been created using generic AI models trained on copyrighted art. In fact, many of the featured artists work with their own datasets or design custom AI tools. According to the petition, however, the auction house’s irresponsible association with these artists would “reward and further incentivize AI companies’ mass theft of human artists’ work.”

Right: Central Park Nightfall, 2025

Though impassioned, this argument failed to acknowledge a key distinction between Ambrosi and his peers on the one hand, and the many thousands who signed the petition on the other. This latter group is made up predominantly of commercial artists, like illustrators and graphic designers, whose livelihoods are indeed, unfortunately, at risk from the efficiency and affordability of AI. Their logic that a machine that can easily imitate an artist is necessarily a threat cannot, however, be applied to the fine artists included in the Christie’s sale. As is the case for all art that makes it to auction, their work’s value lies instead in its prestige, uniqueness, and authenticity, rendering replicas pointless.

Like many of his peers, Ambrosi was unfazed by the petition. If anything, it brought to mind some of the backlash met by historical avant-garde movements, most particularly the Impressionists, who proudly accepted a name that had originally been used as an insult by the French critic Louis Leroy. “It only helped draw attention to the exhibition and Impressionism

became one of the most beloved art movements of all time,” he said. As was the case for Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Berthe Morisot working in paint in the 19th century, fine artists who work with AI seek not merely to adhere to pre-established formulas for making art – or, in this case, to remix what has come before, as straightforward AI image-generators have been trained to do –, but to explore their tool’s capacity to invent new ways of seeing. As in the case of Ambrosi and his Dreamscapes, this is, inevitably, a human-led endeavour. Much like their Impressionist forebears, it is only by fully embracing their own, distinct perspective that these artists are able to find a universally affecting lens on our world. Taken together, these works tell us something original about their era.

An Emerging Market

The frenzy of excitement with which the internet greeted the first generation of text-to-image generators like OpenAI’s DALL-E, now ChatGPT, and Midjourney stirred up widespread debate around “AI art.” Was it valid? Could machines make art? Unfortunately, much of this conversation promoted the common misconception that art made using AI is something new, having originated in around 2022. As the practices of Ambrosi and many others prove, this is far from the truth.

The painter-turned-programmer Harold Cohen is usually recognized as the first AI artist for pioneering work first conceived in the late 1960s. It was as a visiting scholar to Stanford University’s Intelligence Lab that he built AARON, the world’s first AI intended for autonomous artmaking by way of a “freehand line algorithm,” which produced lively, irregular lines suggestive of a human artist’s spontaneity. This unlikely, unprecedented achievement caught the attention of notable museums, including the Tate Gallery in London, which gave Cohen a show in 1983. There, he sold some of AARON’s outputs to visitors for cheap, but the mainstream market never woke up to these cutting-edge developments. Cohen, who had previously found considerable commercial success in the traditional art world as a painter – one who had exhibited at Documenta and the 33rd Venice Biennale in 1966 – resorted to giving away some of AARON’s artworks for free and significantly undercharging for those to which he had contributed. Only decades later has the expected causal

Central Park Nightfall (detail), 2025

relationship between institutional recognition and growing collector interest finally emerged. Since a landmark retrospective dedicated to Cohen at the Whitney Museum in New York in the spring of 2024, the prices of AARON’s computer drawings have doubled to over $10,000, at least, for a single sketch in ink on paper. The artist’s record was set at nearly $18,000 for a 1984 computer drawing in July at Sotheby’s New York.

In the early days of Ambrosi’s practice, he too was predominantly appreciated by scientific rather than artistic circles. Shortly after his Dreamscapes series debuted at the NVIDIA GPU Technology Conference in San Jose, CA in April 2016, he was quick to secure local representation with regional galleries in Miami and West Palm Beach. However, over the following few years, most opportunities to exhibit or speak about his work came via computer science

conventions, like the Neural Information Processing Systems conference of 2018 or the Stanford Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence Institute launch event in 2019. Ambrosi only began to observe serious market interest in his work picking up steam after 2020, with the rise of NFTs. He wasn’t the only one. “I was surprised by how many people were buying that had never bought an artwork before,” according to digital art advisor Georg Bak. “That’s when I realised that the art market is going to change. Young people are tech savvy and for them this is the art that they want to see.”

While the sales volume on Web3 marketplaces has waned considerably since its peak in 2021 and 2022, a wider recognition and appreciation for digital art has happily endured. Now, the focus is narrowing considerably onto those artists who are able to stand the test of time.

In recognition of his decades-long research, Ambrosi’s work has been acquired by relevant institutional collections, including the Computer History Museum in Silicon Valley and the online Museum of Contemporary Digital Art, both in 2023. Since then, Ambrosi has gone to appear in high-profile market contexts, including the inaugural Digital Art Mile, coinciding with Art Basel, and Frieze Seoul, both in 2024. The academic foundation of his practice has, however, remained its central drive. In the summer of 2024, Ambrosi returned to his alma mater Cornell University as an artist-in-residence. In the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, he had studied architecture and computer graphics and, over six weeks at the college’s Program of Computer Graphics, he would once again be under the supervision of his ex-teacher Dr. Donald P. Greenberg, as well as Dr. Alex Kwan, an associate professor at the Meinig School of Biomedical Engineering. His research built on the discoveries that came to light while preparing for his inaugural solo exhibition with Robilant+Voena in London in the fall of 2023. Then, he presented Dreamscape interpretations of the sweeping vistas of classically English gardens by 18th-century landscape designer Capability Brown, complete with elegant bridges and rotundas. The project inspired a deeper exploration into the intangible relationship between landscapes and memories, and the rich associative emotions that these spaces may consequently activate.

Ladies Pavilion (detail), 2025

New Ways of Seeing

While, since 2021, the mainstream art world has become increasingly au fait with digital art, most opportunities for its appreciation have continued to be siphoned off onto separate platforms, satellite fairs, and specialist exhibitions. It is for this reason that many in the digital art space embraced the recent news that Christie’s had closed its digital art department, instead folding these sales into its much larger 20th and 21st Century Art category. Robilant+Voena, with its expertise spanning from the Old Masters to modern and contemporary art, has long led the way in contextualizing digital art within our broader understanding of art history, where it belongs.

It is Ambrosi’s aim “to more effectively convey the power of special places and fully express the experiences I was having in the presence of great landscapes and cityscapes,” that makes the comparison to Impressionism particularly apt. Having developed his “XYZ” computational photography technique, which merges dozens of photographs into one vast panoramic vista, he realised that the whole truth of an experience couldn’t be captured merely by achieving greater and greater clarity. It was the same impulse that pushed the Impressionists to reject the contrived academic painting style so acclaimed by critics, in pursuit of something more honest. Ambrosi too needed to invent a method that would imbue his crisp, hyperreal images with greater expressivity. His experiments with Google’s “DeepDream” computer vision program, released in 2015, led to a collaboration with Joseph Smarr at Google and Chris Lamb at NVIDIA to build a custom version of the tool.

The ten AI-augmented pictures from the Central Park series on view at Robilant+Voena are derived from panoramas captured during a five-day expedition in the spring of 2013. Earlier this year, the images were remastered from scratch and enlivened with a moving, lyrical quality thanks to the processes that Ambrosi has developed over the past twelve years. Instead of an Impressionist’s loose and rapid brushstrokes, the surfaces of these works now surge with repeated, labyrinthine geometric forms that, in many

Right: Azalea Walk (detail), 2025

cases, echo and amplify those found in nature. In Azalea Walk, the irregular twists and turns of bare branches take on a surreal quality, swirling into the surrounding blue. Just below, freshly bloomed flowers become molten masses of magenta. The sky’s reflection on the lake at Peebler Point is an undulating blur that sacrifices unnecessary detail in favour of foregrounding the scene’s luminosity.

Although the full intricacy of these visual effects can be enjoyed using a “deep zoomable” feature online, the images also transcend their digital origins to join artworks of all kinds in the physical realm. These eye-catching prints, often but not always backlit, easily command a room thanks to the brightening effect of their light boxes. In this way, Ambrosi proposes one elegant solution to the dilemma of bringing digitally-native work to life without relying on clunky screens. It is an innovation that will likely be adopted by others.

Peebler Point (detail), 2025

The backlash against the Christie’s sale, before its eventual success, may have been the last gasp of a reactionary movement aimed at denying the huge potential of experimenting with AI for all manner of artistic practices. Ambrosi’s development over decades of an AI-augmented approach to creatively modify his own original photography, speaks for itself as a reproach to the tired argument that AI art is necessarily unconsidered, lazy, derivative or even new. Yet, as Ambrosi himself has noted, these allegations have the ring of inevitability, having been made many countless times before. The use of AI in many fields, including art, is becoming increasingly ubiquitous. As ever, examples of obvious quality will stand out.

Jo Lawson-Tancred is an experienced art journalist with a particular interest in the use of tech in artistic practices and in art businesses. Her book AI and the Art Market was published by Lund Humphries in 2024. She has written for Artnet News, Apollo magazine, the Financial Times, the Guardian, BBC Culture, and Canvas magazine.

Azalea Walk (detail), 2025

Click on each artwork to view the high-resolution image ▶

Ambient-lit dye-sub fabric print

162.6 x 203.2 cm (64 x 80 in)

Edition of 3 (#1/3)

Ramble Stone Arch, 2025

Cove, 2025

Ambient-lit dye-sub fabric print

111.8 x 243.8 cm (44 x 96 in.)

Edition of 3 (#1/3)

Wagner

Bridge, 2025

Ambient-lit dye-sub fabric print

152.4 x 233.7 cm (60 x 92 in.)

Edition of 3 (#1/3)

Oak

Central Park Nightfall, 2025

LED perimeter-lit dye-sub fabric print

182.9 x 76.2 cm (72 x 30 in.)

Edition of 5 (#2/5)

Right:

Central Park Nightfall (detail)

Corporate collection

The Pond, 2025

Ambient-lit dye-sub fabric print

182.9 x 243.8 cm (72 x 96 in.)

The Lake, 2025

Ambient-lit-dye-sub fabric print

182.9 x 243.8 cm. (72 x 96 in.)

Corporate collection

Ambient-lit dye-sub fabric print

121.9 x 243.8 cm (48 x 96 in.)

Edition of 3 (#1/3)

Peebler Point, 2025

Azalea Walk, 2025

Ambient-lit dye-sub fabric print

182.9 x 243.8 cm (72 x 96 in.)

Ambient-lit dye-sub fabric print

101.6 x 101.6 cm (40 x 40 in.)

Edition of 5 (#1/5)

Ladies Pavilion, 2025

Ambient-lit dye-sub fabric print

Bow Bridge, 2025

182.9 x 243.8 cm (72 x 96 in.)

Ambient-lit dye-sub fabric print

142.2 x 243.8 cm (56 x 96 in.)

Edition of 3 (#1/3)

Balcony Bridge, 2025

Ambient-lit dye-sub fabric print

121.9 x 121.9 cm (48 x 48 in.)

Edition of 5 (#1/5)

Belvedere Castle, 2025

Biography

Daniel Ambrosi (born 1958) is a visual artist specialising in digital and AIaugmented art. He studied at Cornell University, where he received a Bachelor of Architecture and a Masters in 3D Graphics. He has practised digital art for over 40 years, and starting in 2015, with engineering assistance from Joseph Smarr (Google) and Chris Lamb (NVIDIA), developed an enhanced version of Google’s ‘DeepDream’ technology, a tool central to his large-scale immersive Dreamscapes

Ambrosi’s practice is deeply informed by the history of landscape painting, finding particular inspiration in the works of the grand format landscape artists of 18th- and 19th-century Europe and the later 19th-century Hudson River School artists.

Ambrosi’s works have been shown in exhibitions and fairs across the United States and in Europe; his work has recently been acquired by the Museum of Contemporary Digital Art (MoCDA), and in 2019 he was a finalist of the Lumen Prize for Art and Technology. Ambrosi undertook a residency at Cornell University in Summer 2024, and his work featured in the groundbreaking auction at Christie’s New York in February 2025, Augmented Intelligence, the first of its kind dedicated to AI art.

Selected Recent Exhibitions

2025

The Green World of Brown, Weston Park, Shropshire, UK

Augmented Intelligence, Christie’s, New York, NY

Contemporary Discoveries, Sotheby’s, New York, NY

2024

Chatbots Decoded: Exploring AI, Computer History Museum, Mountain View, CA

deeep AI Art Fair, Paris, France

2023

Daniel Ambrosi. AI and the Landscapes of Capability Brown, Robilant+Voena, London, UK

The Perfect Error, curated by Luba Elliott, UNIT London, UK

deeep AI Art Fair, Miami, FL

2022

Focus Art Fair, Paris, France

deeep AI Art Fair, London, UK

2019

Google, New York, NY

Google, San Francisco, CA

Art Palm Beach, FL

Stanford Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence Symposium, Stanford University, CA

2017

Google, New York, NY

Google, San Francisco, CA

Notable Collections

Bowood House, UK

Computer History Museum, CA

JPMorganChase, New York, NY

Museum of Contemporary Digital Art

Daniel Ambrosi (left) working with Professor Donald Greenberg (right) and fellow graphics researchers at Cornell University, 1981.

Image: Emil Ghinger.

Published on the occasion of the exhibition

Daniel Ambrosi: Central Park

24 October – 4 December 2025

Robilant+Voena

19 East 66th Street, New York, NY 10065

Publication © Robilant+Voena 2025

Edited by Helen Record

Texts:

© 2025 Tim Barringer

© 2025 Jo Lawson-Tancred

Designed by Footprint Innovations Ltd

Image credits:

P. 12, Fig. 1: © The Trustees of the British Museum

P. 12, Fig. 2: Image courtesy of Nelson-Atkins Digital Production & Preservation.

P. 15, Fig. 4: The Picture Art Collection / Alamy

P. 16, Fig. 7: © The Trustees of the British Museum

P. 18, Fig. 11: © David Hockney. Photo Credit: Richard Schmidt

P. 19, Fig. 13: Albertinum, Dresden State Art Collections

All works by Daniel Ambrosi © the Artist.

Cover images:

[Front] Daniel Ambrosi, Azalea Walk (detail), 2025.

[Back] Daniel Ambrosi, Balcony Bridge (detail), 2025.

robilantvoena.com

Right: The Lake (detail), 2025