Official Boat Supplier of USRowing U19 and U23 Teams

Unlock the next tier of LiNK LogBook.

Optimize your training and performance with:

• Enhanced session sharing

• Multi-boat views

• Real-time boat tracking

Stop by our booth at Head of the Charles, Head of the Schuylkill, or Head of the Hooch for product support and new NK merch. Sign

Coach Tier: Elevate your coaching with private live streaming + multi-boat view.

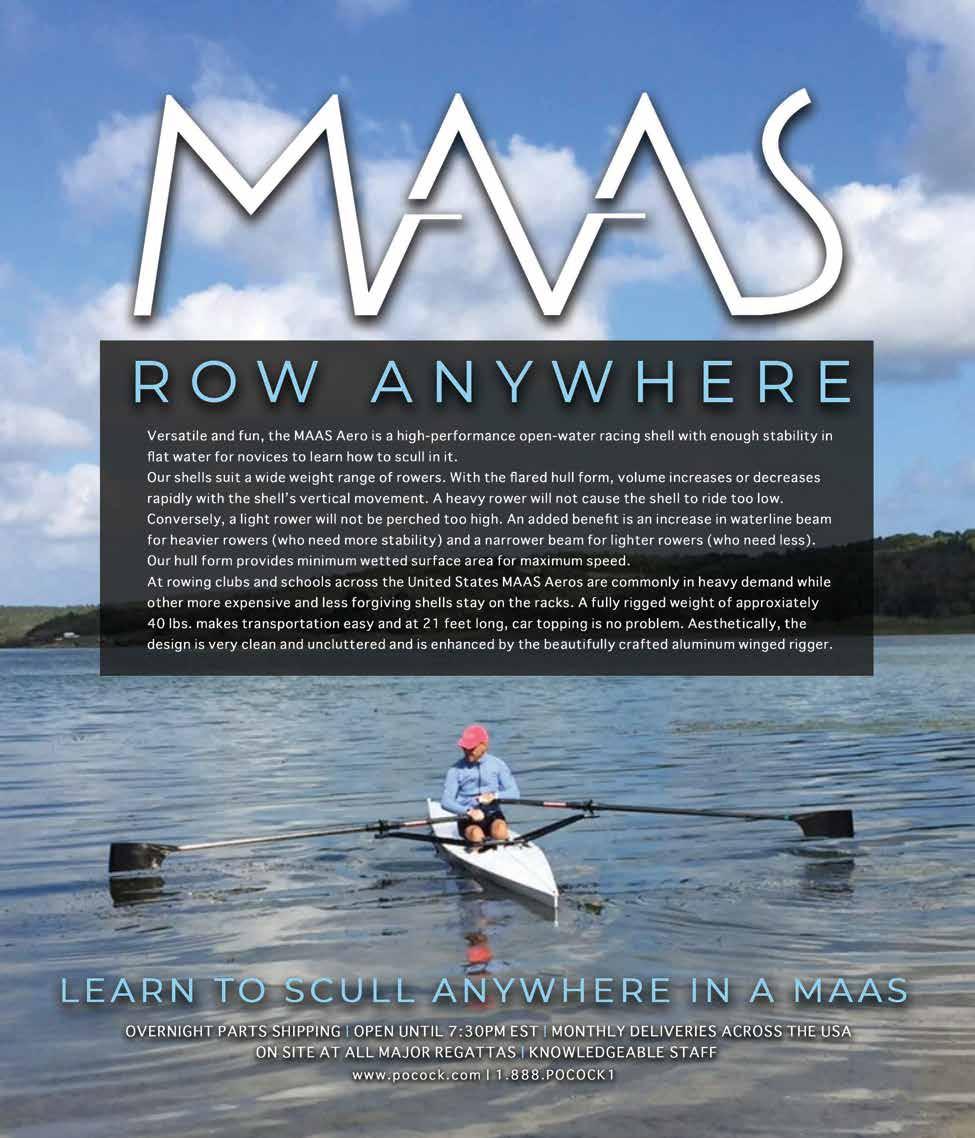

At 25 Lbs. the Lightest Singles in Production

• Less Drag, More Speed

• Lighter Feel, Higher Stroke Rate

• Easier to Carry

Follow Rowing News

FEATURES

Build a first-rate racecourse. Elevate a Midwestern rowing program. Give lightweights a chance to compete. Lead college rowing coaches. What will Kemp Savage do next?

BY KATIE LANE

When those of us who rowed in college live in a place with no rowing club, we feel compelled to create one.

BY AMY WILTON

The Canadian Olympic coach set out to be a psychologist and fell into coaching rowing accidentally.

BY CHIP DAVIS

DEPARTMENTS

News CRCA and IRCA Salary Surveys AEDs in Boathouses

Sports Science Getting Ahead at Head Races

Coxing The Confidence Game

Recruiting ‘I’m Not Recruitable. Now What?’

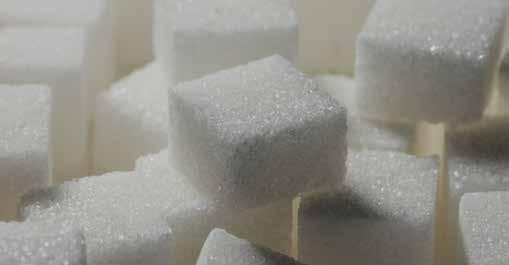

Fuel Sugar: Friend or Foe?

Training Prepping for Fall Head Races

Coach Development Taking Advantage of Turnover

14 From the Editor 66 Doctor Rowing

CHIP DAVIS

In his column this month Doctor Rowing writes, “Scratch any rower and he’ll tell you who helped him rise.”

That’s certainly the case with Olympic champion Pete Cipollone, winner of seven Olympic and worlds medals (five of them gold) back in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when the U.S. National Team ruled the world in eights.

Cipollone credits coach Mike Teti with “one of the most important pieces of coaching I ever got,” which you can read in this month’s Coxing column by George Kirschbaum on page 58.

Head coaches at the top college programs benefit from better pay owing in part to salary surveys.

Teti continues to foster U.S. Olympic success, coaching at California Rowing Club, where most of the U.S. National Team men’s four and eight that won Olympic gold and bronze in Paris trained when they weren’t in USRowing selection camps or on training and racing trips.

Clubs provide essential opportunities and support for athletes outside of the schools and universities that expose most rowers to the sport for the first time. The head coaches (if not the assistants) of the top collegiate programs benefit from better pay owing in part to the salary surveys of their coaching associations, the Collegiate Rowing Coaches Association (for women’s programs) and the Intercollegiate Rowing Coaches Association (for men’s). Read more about it in Big News, page 25.

As opportunities to walk on to a college varsity program as a novice disappear, clubs become an even more important part of our sport. Beginning on page 36, Amy Wilton tells the instructive stories of the advent of several clubs founded through the passion of rowers bent on sharing the transformative power of our great sport with others.

May it inspire you to do the same.

After two consecutive years of trying to enter one of my athletes who has proven to be one of the top youth scullers in the country into Head of the Charles, only to have her waitlisted both times, it dawned on me: Why can’t HOCR use a merit-based system for youth single events? It’s the only event in rowing where the rower represents the entry 100 percent.

In addition to “10 Ways to Save Rowing” (June issue), I suggest adding an 11th: Make singles entries based on merit. Though I’m referring specifically to Head of the Charles, this could be applied to other races where entries are at a premium, and it may make some regattas more attractive to faster single scullers.

Head of the Charles boasts of being the most prestigious regatta in the country and hosts athletes and teams from across the nation and around the world. Why wouldn’t the regatta committee want the most diverse group of fast athletes racing for medals in this event? As it stands, there are typically about 45 spots available for women’s and 50 spots for men’s youth single entries at the Charles.

The athlete at my club rows on a very small team in a part of the country

where rowing isn’t well known, and she has dedicated a lot of extra effort because of her love of the sport. She has put in countless hours with the team and on her own to become the best athlete she can be. Unlike the Charles River, there are no rival boathouses on our body of water, no early-morning rows alongside other strong competitors to inspire our athletes to get faster every day. I would argue that it’s more difficult to train without a large team pushing you on.

At HOCR, there are five more entries available in the boys’ singles event than in the girls’, which are allocated specifically for local clubs along the Charles River. These club members have the opportunity to row this iconic river every day. Why not reward a well-deserving female athlete who has overcome the disadvantage of her geographic location and who may never have another chance to race in such a legendary event?

To make this a merit-based system, there’s a simple solution. The committee would gather the names of the athletes who made the grand finals at USRowing Youth Nationals in the youth and U17 singles, and the grand final from Scholastic Rowing Association of America nationals in the senior single. HOCR organizers would extend invitations to those athletes directly or wait to see who registers and make sure

they are priority entries. That would mean monitoring 18 to 22 athletes of each gender.

I imagine there would be some overlap with guaranteed entries, and several athletes would have graduated to college programs or wouldn’t be interested in racing. With 10 to 15 merit-based entries for each gender, there still would be plenty of entries available for the regatta’s traditional lottery system.

HOCR invitations would be an honor to receive and a goal for which rowers could strive. The impact of such an opportunity for small-club rowers would be far-reaching. Beyond the incredible rowing experience for the athlete, it would bring attention to the rowing club, thereby motivating other young rowers to strive for such success, inspiring others to try the sport, and stirring regional interest in the sport through media coverage.

Imagine what a handful of these fast rowers from all corners of the country could do to promote this niche sport, increase participation, and help strengthen USA sculling as a whole on the national stage.

Ted Riedeburg Director, Head Coach

Rock City Rowing and Episcopal Collegiate School Little Rock, Ark.

Independent review of the ActiveSpeed - Sander Roosendaal, founder of the rowing analytics site rowsandall.com, takes a deep dive into the ActiveSpeed. Radley

Large Configurable Display (2, 4 and 6 fields)

Optional Wireless Impeller & Accessories

Easy Data Transfer via the DataFlow App

$445 $495

Members of the German National Team shove off from the dock for a training session. Shanghai hosts the 2025 World Rowing Championships, September 21-28. Overnght.com will live-stream all eight days of racing.

A

of oars

Train like champions at Nathan Benderson Park. Recognized as North America’s best rowing venue, NBP provides elite facilities and seamless support—so your team can focus on results.

Benefits

• World-class rowing venue in Sarasota, FL

• Perfect training climate, with great weather and calm conditions

• Just 1 mile from I-75 with ample trailer parking

• 550-acre park with trails for walking, running and fitness

• 5 miles from airport, walking distance to shops and dining, minutes from world-renowned beaches

Many head rowing coaches consider their positions dream jobs unlikely to be improved by change, although many complain about the low wages.

The pay of head rowing coaches varies widely—from less than $50,000 to over $300,000–surveys by the sport’s two coaches associations show.

Division I NCAA women’s head coaches make more (median pay: $107,499) than IRA heavyweight men’s head coaches (average $85,000 to $99,000).

Power 4 conference (Big 10, Big 12, ACC, and SEC) women’s head coaches were paid even higher salaries, with median compensation of $137,499. Median pay for NCAA Division II head coaches was $54,999, and higher for NCAA Division III head coaches at $72,499.

“We do these surveys as a service to our members and the sport in general,” said Chris Clark, co-president and co-founder of the Intercollegiate Rowing Coaches Association, for male coaches. “Without them, it’s an opaque market—to the disadvantage of the coaches.”

The survey by the Collegiate Rowing Coaches Association, for female coaches, received 73 responses, with 62 disclosing salary data. The IRCA survey collected responses from 55 institutions, representing 95 percent of the association’s membership, with 46 completing the full survey. Many coaches’ salaries and contracts are public information, available online and through information requests and reporting services.

“Things being more public is only good, for the coaches,” said Texas head coach and CRCA board member Dave O’Neill, “even if it’s uncomfortable.”

Most of the coaches contacted about the salary surveys were unwilling to comment on the record—a reflection of the sensitive nature of the subject as well as the tendency of rowing coaches to avoid controversy. Many head rowing coaches consider their positions dream jobs unlikely to be improved by change, although many complain about the low wages.

Each survey broke down pay by position—head coach, associate head or first assistant coach, and third assistant—and conference. Benefits like health insurance, retirement plans, and leave were common among all leagues and both surveys. Club memberships and cars were among the benefits listed in coaches’ contracts, as were additional job responsibilities, such as meeting with local businesses and running summer camps.

The CRCA survey did not address funding sources, while the IRCA survey noted a variety of ways coaches get paid, commonly through booster, alumni, and charitable family foundations.

Last year, the eventual national champions lost their regular-season contest against their bitter rivals but won the season finale against another program when the rivals failed to advance to the final. That storyline earned Ohio State’s head football coach, Ryan Day, over $10 million in compensation from his Big 10 school.

The same storyline earned Washington men’s rowing head coach, Michael Callahan, less than three percent of that— about $330,000 total salary, mostly earned through performance bonuses—making him the highest-paid men’s college rowing coach in America.

(Ryan Day’s total makes him only the fifth-highest-paid college football coach. Top of the heap: Georgia’s Kirby Smart, at over $13 million).

At the 2024 Olympic Games, 17 Huskies competed, winning 11 total medals. Callahan coached the U.S. men’s Olympic eight, winners of the bronze medal—with four Huskies on board. As this issue went to press, 22 Huskies headed to Shanghai to compete in the 2025 World Rowing Championships, with the largest number of them there to compete for the United States.

Callahan and Washington’s head

women’s coach Yaz Farooq were paid roughly the same amount the year before, according to Washington state data, which likely makes Farooq the top-paid women’s coach.

Private institutions, like NCAA DI team champion Stanford and DI varsity eight winner Yale, do not report salaries and contracts publicly.

The pay disparity gets even worse among assistant coaches. Ohio State’s football staff has seven members making over a million dollars each, and the 11th-highest paid staffer—linebackers coach James Laurinaitis, who took home $350,000—still earns more than the top rowing coaches. The average assistant coach, according to the IRCA salary survey, makes about $50,000.

Comparing rowing to college football, with its billions of dollars in TV revenue, is apples to watermelons at best, of course. Comparing rowing to track & field, with its large rosters of student-athletes racing in an Olympic sport, is more apt.

There again, however, colleges underpay rowing coaches compared to their peers. For example, Ohio State paid women’s rowing head coach Emily Gackowski $160,000 and track & field/ cross-country head coach Rosalind Joseph $212,180—over $50,000 more—despite the fact that rowing typically serves a bigger roster.

Rowing, along with every other sport that is not football or basketball, faces an uncertain funding future as the NCAA falls apart in the wake of the Supreme Court’s NCAA antitrust decision and settlement, which allows college athletes to be paid directly, players to profit from their name, image, and likeness (NIL), and massive increases in TV broadcast payments to football conferences.

Football programs today spend as much as they

CONTINUES ON PAGE 26

Helping rowers worldwide get scholarships

Helping high school rowers and families navigate the university recruiting process- Coaches and parent groups reach out to us!

Robbie Consulting will meet your team, coaches and parents at your home club or school. Go to www. robbieconsulting.com to get in touch and schedule a visit

“His assistance was essential to get prepared for such a big step and to get to know the school and team I would compete for.” Visit the Gay + Lesbian Rowing Federation booth at the 2025 Head of the Charles Regatta© Stop by and learn about the 2026 Sin City Erg The Global LGBTQ Indoor Rowing Event Early registration opens 01 October 2025

www.robbieconsulting.com

1-614-330-2879 • Robbie@robbieconsulting.com

BIG NEWS >>> receive for broadcast rights (and sometimes more), The Atlantic reported recently. Result: The vast increase in revenue has not produced balanced budgets or surpluses to support non-revenue sports.

Among college Olympic sports, a further division between those that charge admission (volleyball, softball) and those that don’t (rowing) has led some universities to set up NIL opportunities for “ticketed” sports and not for others.

Much attention has been paid to the rise of international recruits in both men’s and women’s varsity rowing programs (funded by a school’s athletic department as opposed to club programs, which are funded by student activity fees and dues). A commonly expressed concern has been whether the displacement of domestic athletes by internationals has hurt the development of U.S. Olympic rowers. The salary surveys, however, finger a more likely culprit: the demise of novice and freshman programs and their coaching positions.

The top assistant rowing coach used to be the freshman or novice caoch. Not so anymore. Instead, those positions have been replaced almost totally by recruiting coordinators.

Practically no walk-on opportunities exist in the top IRA and NCAA Division I programs—sources of the entire 2024 U.S. Olympic squad (with the exception of threetime Olympian Meghan Musnicki, who began rowing at Division III St. Lawrence University).

Some of the most successful U.S. Olympic rowers ever, such as Susan Francia, who, like Musnicki, is a two-time Olympic rowing gold medalist, learned to row in college. Today, that opportunity barely exists in Division I rowing, the surveys show. One coach said he would be laughed out of his athletic administration offices for even suggesting the reinstatement of a novice coaching position. There is no real pathway to the Olympics in U.S. rowing besides Division I varsity programs, currently.

Following the money is a good way to understand how a situation came to be. The CRCA and IRCA surveys help head coaches receive better pay for the valuable work they do, but more TV money hasn’t led to more opportunities for student-athletes—the ostensible purpose of college sports.

Dr. Ann Redgrave, chief medical officer for Great Britain’s rowing team, has called for all rowing clubs to have automated external defibrillators (AEDs).

“It disturbs me that there remain many rowing clubs that do not have their own defibrillation equipment,” Redgrave said.

AEDs are portable devices used to treat someone experiencing sudden cardiac arrest, often found in public spaces like government buildings, schools, and airports. While training on proper use is recommended, the Mayo Clinic says someone with no training could use an AED to reset the heartbeat of someone experiencing sudden cardiac arrest. Using an AED could save a life, the Mayo Clinic

• Pre-Design

• Site Analysis

• Site Layout and Planning

• Space Requirements

• Equipment Layouts

• Concept Studies

• Feasibility Studies

• “Simple Boathouse” advising

• Full Architectural Services or Partner with another firm

• Rowing Tank Design

advises.

“Every year, we learn of instances in which participants in our sport have unexpected events in which heart or circulatory problems have put their wellbeing at risk,” Redgrave said. “We know that defibrillators save lives, and relying on the chance of having access to a machine five minutes up the road from the boathouse is not good enough.”

AEDs range in price from $1,000 to $2,500, but British Rowing has a partnership with a charity that provides free defibrillators in the United Kingdom. The American Red Cross has a discount program that requires clubs to contact them directly.

The brand logo of Humann, maker of nutritional supplements, will appear on 11 University of Texas athletic facilities, including the Longhorns’ football field and boathouse.

“What starts at Texas changes the world,” said Texas athletic director Chris Del Conte, of Humann, which grew out of a University of Texas Health Science Center research program.

“If we were going to make the decision to put a brand on our fields, courts, and across all our athletics venues, it had to have an incredible story. What began with Texas researchers has been used by our student-athletes for over a decade to help them perform better on the field and aiding people to be at their best heart health for everyday life.”

This will be the first time that a commercial logo appears next to the iconic Texas Longhorn at the university boathouse, as well as 10 other athletic facilities.

Planning, + Consulting for Rowing

Bates College • Bergen County

Brunswick School • Culver Academies • Episcopal H.S. of Jacksonville • Foundry, Cleveland • Harvard University • MIT

• Mt. Holyoke College • Princeton University • St. Paul’s School

• Tufts University • University of Kansas • University of Wisconsin

• Wellesley College • Washington State University • Williams College • WPI • SERVICES:

BUILD A FIRST-RATE RACECOURSE. ELEVATE A MIDWESTERN ROWING PROGRAM. GIVE LIGHTWEIGHTS A CHANCE TO COMPETE.

One measure of a successful life is how close you’ve come to achieving your goals. Kemp Savage’s abiding goal has been to give back to the sport that has given him so much.

Consider what the energetic 42-year-old head rowing coach at Eastern Michigan University has achieved so far:

• added a new national championship-caliber racecourse in a country with a short supply;

• elevated a Division I rowing program in the empty space between the coasts;

• introduced a new varsity program for lightweight rowers to augment their dwindling ranks;

• taken command of the Collegiate Rowing Coaches Association at a time when it needs new leadership desperately. But that’s just scratching the surface. Savage’s real impact shows through his dedicated involvement in the rowing community, where he both creates and advocates for change. A student as well as teacher of the sport, he shows those around him that change is possible.

Many in rowing considered some of the problems Savage has solved intractable. But Savage is one of those people, evidently, for whom a challenge is enticing in proportion to how daunting. When

he sees a problem or a place that could use improvement, he first looks inward and asks how he could effect change. If it’s something he can’t do himself, he finds the right people to get the job done.

Those who know him laud his vision and ability to think through complex issues.

“Kemp has a unique ability to see the bigger picture,” said Delaney McGuire, EMU’s associate head coach. “Whether handling situations within our own team or in the bigger rowing world, he takes the time to consider the aftermath of the actions he is taking and whether what we are doing today moves us closer to our goal. Kemp is action-oriented. He gets things done.”

Savage also knows how to build rowers—more than seven years coaching on the international stage with the World University Games, more than 11 years as the head coach at Eastern Michigan University, where he earned his master’s degree in exercise physiology and has led EMU to the highest finishes in program history—three fourth-place finishes and three third-place finishes at the Colonial Athletic Association championships.

A native of Chesapeake, Va., Savage earned a bachelor’s degree in biology at the University of Mary Washington in Fredericksburg, Va., where he lettered in rowing all four years. While Savage was at UMW, the team he captained made the finals of the Dad Vail Regatta and the Eastern College Athletic Conference championship regatta.

Savage began his coaching career at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, where he was assistant coach of the club rowing team before taking over as head coach in the 2007-08 season. Under Savage, the ODU men’s novice team placed first at the American Collegiate Rowing Association nationals and the women’s varsity placed third.

“It is hard to put into words all that I have learned from Kemp.” McGuire said. “Yes, I have learned the x’s and o’s of rowing, trailer driving, equipment maintenance, and all the things you would hope to learn as an assistant, but the lessons that stand out the most to me are: You can learn something from everyone, even people you may not agree with. Do things the right way, even if the right way is the long way. If you want a say, you need to be in the room. And always dream big.”

If you build it, they will come

Designed by Olympic course architect Tim Royalty, the $487,000 submersible course on Ford Lake in Ypsilanti, Mich., features eight competition lanes, floating launch and recovery platforms, and the capacity to host regional, national, and international events. National competitions have the potential to enrich the local community by as much as $3 million.

Years ago, Savage and other community members conceived the idea of building a course that in 10 years could accommodate major rowing competitions. Efforts to secure funding and partnerships continued over many years and rebounded after being slowed by Covid.

Ford Lake proved its ability to accommodate large-scale events last summer when it hosted the 2025 USRowing RowFest National Championships, which attracted 136 clubs and thousands of spectators the last two weeks of July.

“We had over 2,600 participants here for RowFest over nine days,” said Scott Weatherbee, EMU athletic director. “We also hosted a camp for three weeks on our campus, and they were on Ford Lake.

“These are people going out into our community and spending

money. It’s a great economic impact. They’re filling hotel rooms, and we get to showcase Ypsilanti in Southeast Michigan. It worked out really well.”

The new course will benefit EMU by providing a home course and reducing travel expenses, Weatherbee said, as well as hosting the inaugural Mid-American Conference (MAC) rowing championships in 2026. Bringing more racing opportunities to Ford Lake will allow more junior athletes to experience rowing in Michigan.

In the wake of the NCAA antitrust settlement, as EMU was exploring ways to increase athletic participation for women, Savage suggested adding another varsity rowing program.

“I presented a plan to our administration to add lightweight rowing—using current facilities, having our own venue and existing infrastructure to make lightweight rowing the first addition to the department and an expansion of DI rowing opportunities for female athletes,” Savage said.

“Adding lightweights won’t be a big expense, as they can work simultaneously with our openweight program,” said EMU athletic director Weatherbee. “You’re looking at adding 15 to 25 young women, giving them an opportunity that we didn’t have before. It helps with enrollment, it will have minimal budget impact, and there’s a big upside for the rowing community.”

the international stage

When invited to coach rowers competing at the World University Games in 2018, Savage regarded it as “an opportunity I couldn’t pass up.” He coached these aspiring young athletes again in 2024 and 2025, with medal performances to show for his efforts.

“It’s a great opportunity to find out if international racing is something you want to do and something you want to keep driving toward,” Savage said. “These kinds of camps are open to people who might not be quite ready for the world championship or Olympic camps but need the experience of how to row a camp.”

Ford Lake and EMU have been ideal hosts for the three-week camp and served as the training center in 2018, 2024, and 2025.

“It has been a great chance to work with top-tier, driven athletes and build boats that compete for the U.S.,” Savage said, “while also developing athletes who take that experience back to their home teams and share other opportunities to race internationally if they don’t make the U23 selection camp.”

For Savage too, it has been broadening and enriching.

“It is great to hone my coaching skills with different athletes and try new teaching methods with more experienced rowers before implementing them with my team,” he said. “It is also great to get out of the U.S. and see how rowing is approached in other countries and how they treat competition like the World University Games.”

Savage coached the American women’s eight that won gold in 2024 and the American women’s eight that earned bronze last summer in Rotterdam.

“Kemp is a fierce competitor and brings that energy to the megaphone when needed,” McGuire said. “He is a big believer in teaching the athletes about the physiology and biomechanics behind what we are doing and does not hesitate to go in depth with them. He has always told me that athletes will rise to the level of expectation that we have for them, so why not set it high and why not teach them everything.”

Promoting rowing off the water

Delaney McGuire, who has been with Kemp since 2016, believes that the work Savage has done at EMU has put him in rooms where he can impact rowing in a major way. Prime example: EMU’s involvement in the evolution of the Mid-American Conference.

“He worked with our athletic director to add rowing as a sport in the MAC,” McGuire said. “This not only allows us to compete in our home conference but also offers a home to a number of programs facing conference realignment, increases the number of automatic qualifiers at the NCAA championship, and opens a pathway for other MAC schools to entertain the idea of adding rowing as a varsity sport.

“I firmly believe we cannot live in a world where we focus only on our own teams. College coaches have a responsibility to strengthen rowing not only at the college level but also nationally and internationally.”

Savage, who has held numerous positions on boards and committees, including the CRCA Sustainability Committee and the NCAA Rowing Championship Committee, believes such participation is necessary for the sport’s success.

“Rowing has given me a place as a high-school athlete, college athlete, and now as a profession,” Savage said. “If I don’t do everything I can to repay that and ensure it’s built out for future athletes, then I’ve been too selfish and haven’t paid the sport forward.”

His appointment as CRCA president last April, Savage says, is the first step toward realizing that laudable ambition.

“With the changing landscape of college athletics coming out of Covid, and now the new House settlement, we have to stand up as advocates and stewards of college rowing. I know that making our own teams sustainable and safe is a huge concern for many collegiate coaches, but if we don’t take time to look beyond our own programs, we might see the sport disappear at the NCAA level.”

Savage believes that through the collective knowledge and experience gained through decades in the sport, members of the CRCA are uniquely equipped to tackle the challenges facing rowing.

“Coaching has given me a lot of maturity and understanding of who I am and how to communicate with people who aren’t just like me. Coaching has allowed me to be more balanced with results and focused on the outcomes we want to achieve.”

Savage speaks highly of inspiring mentors like Bebe Bryans, former head coach of women’s crew at the University of Wisconsin, and Kevin Sauer, former head rowing coach at the University of Virginia, whom he credits with helping him “step out into the bigger world rather than just be focused on EMU.”

“We all want to win on the racecourse, but we also have to use rowing to teach 18- to 22-year-olds how to be the best people, employees, and family members they can be when they leave,” Savage said.

Over the past eight years serving as EMU’s athletic director, Scott Weatherbee has watched Savage from a close vantage. He has witnessed what a fierce competitor he is and the energy and enthusiasm he brings to his team, the department, and the rowing community.

“He always wants to be first,” Weatherbee said. “He wants to lead community-service hours. He wants to win awards. He wants to be first in everything he does.

“He gets and understands the commitment it takes to be in the rowing community.” KATIE LANE learned the transformational power of rowing as an undergraduate at the University of Vermont and spent more than 10 years coaching at the collegiate level. She currently works as a communications strategist in Philadelphia, combining her expertise in digital marketing, partnerships, and creative storytelling with her passion for sports and community building

When those of us who rowed in college— and are pining for that daily dose of exercise-induced euphoria—live in a place with no rowing club, we feel compelled to create one.

BY AMY WILTON

When I moved to Camden, Maine, in 1997, I thought, “Wow, ocean, mountains, clean air. This is perfect, except there’s no rowing.”

Fast forward a couple of decades: rowing, sculling, and sweep for adults and teens have taken off. The state currently boasts six club programs—two prep schools and four colleges that support rowing teams. Now living in Maine really is “The Way Life Should Be.”

I think it’s fair to say that rowers, in general, are passionate people. Those of us who rowed in college and are now out in the world living our grown-up lives find

ourselves pining for the days when rowing was built into our daily schedule. We want that dedicated time to push ourselves into that incredibly uncomfortable and liberating space of exercise-induced euphoria. So when we live in a place with no rowing club, we feel compelled to create one, allowing us to pass on the love of our sport to the next generation.

Starting a rowing club in a rural setting takes time, tenacity, and fortitude. In 1999, Ry Hills, a former University of New Hampshire rower and the recently retired Bowdoin College coach, found me and said, “I hear you’re a rower. Would you like to help me start a club?” I was thrilled. I think

most rural rowing clubs begin the same way—people move out to the country for the more relaxed lifestyle but miss the community that a rowing club affords.

My friend Melissa Dow started Northern Michigan Rowing Club on Glen Lake and Lake Leelanau for the same reason.

“I saw a bunch of random boats making their way around the lake and wanted to create a support system so they didn’t have to drive an hour to the city every day to row with other people,” she told me.

Rowing clubs come in all shapes and sizes in Maine, just as they do around the country, and scrappy is the word I would use to describe all of them in the beginning. Every person I’ve talked to who has helped found a club has said the same thing, “We did it by the seat of our pants.”

Someone has the great idea to get boats on the water. Then, of course, you need the equipment, the money to buy the equipment, the land to launch the boats, permission from the town to use the land to launch the boats, and the energy to do all that. If you are lucky, you find some wealthy former Ivy League rower who lives in your town and wants to support her favorite sport by donating $50K as seed money, but that’s not how it usually works.

Where to Begin

It all starts with finding the real estate. You need free space on your local body of water where someone will let you store your boats, install a low-profile dock, and permit foot and boat traffic to come through several times a day. Sounds simple, doesn’t it?

At Megunticook Rowing in Camden, we leased land from the town at the public beach for a dollar a year. Down East Rowing, bordering Acadia National Park near Bar Harbor, began with a trailer full of singles that one of the founding members, Charlie Wray, would drive to the public boat launch three days a week, then go to work in his car as he waited for the other rowers to finish their workouts. At the end of practice, he would load the boats back on the trailer and park it in his driveway till the next row. They now have secured rack space in a parking lot across the street from the lake.

Maine Coast Rowing Association (MCRA) in Brunswick leased a tiny square of land next to a boat launch from

the town sewer department. In time, the town approached the club to see whether it would join a dock fundraising campaign because the state’s freshwater access program awards grants once a year. Both the club and town worked together to raise money for a dock that accommodated both powerboats and rowing shells. This was a game changer for the club; after that, they began to grow.

That brings me to another common thread I heard from all the people I interviewed about starting rural clubs: You have to have a great relationship with the town. If you know someone who works for the town and supports your efforts, the process will be much easier. It doesn’t have to be a rower, just someone who can see how the club will benefit the entire community. They can give you the inside scoop on who to speak with, the town regulations, and how to prepare for meetings.

Along with support from the town, you need enthusiasm from the community, since town meetings are often the forum for public discussion about changes to the town’s recreational landscape. Part of the process of creating a new club is teaching the non-rowing community about the sport. Clubs are most successful when they cater to both masters and youth rowing programs, so you’ll have to create enough interest to get people to switch from the sport they’ve always done to this crazy new sport of rowing.

In coastal Maine, there’s plenty of crossover with sailing programs. It’s actually the perfect balance, because people who love to be on the water can row in the spring and fall and sail in the summer.

It requires just a couple people to take the first steps of finding the space, working with the town, and setting up nonprofit status. After that, you’ll need a board of directors to begin digging in to get the club up and running. Eight is the number I’ve heard several times as the right amount of people on the board. The board members create a clear mission, decide whom the club serves (youth, masters, recreational rowers, etc.), and attend to all the details of setting up and running the club.

Boards with clearly defined roles and members who head committees that

involve the rest of the team members seem to have the most success and least amount of burnout. Two- to three-year rotating terms help avoid exhaustion for these volunteer positions.

Typical board executive positions are president, vice president, secretary, and treasurer. These officers oversee the bylaws, policies, and long-term direction of the club and ensure compliance with nonprofit regulations. Committees include finance, membership, equipment, safety, marketing, and programs. If a club is large enough to have a full-time head coach/ executive director, he or she may be asked to oversee equipment, membership, and regattas as well as coaching.

So you have the place and the people to run the program. Now you need boats. Here is where networking comes in handy. You need a boat for your new club, so you call your old college coach and ask if alma mater has any old boats ready for retirement. Typically, the answer is no, but a friend at a school across town does, and so the process of acquiring boats begins.

If that doesn’t work, there’s always the classified ads at row2k. But wait, how will you pay for those brand-new old boats? At Portland Community Rowing Association (PCRA) in Portland, Maine, where I now coach, president Jen Southard said most of their start-up boats were acquired by begging, borrowing, or getting donations from clubs seeking to shed old equipment.

The ideal is to have one board member in charge of fundraising. If you’re super lucky, you’ll find someone who does it for a living and volunteers for the job. If not, it’s a pretty steep learning curve. Some larger more established clubs may have endowments, but newer clubs need to rely on a combination of annual auctions, ergathons, grants, and corporate sponsors to get their feet off the ground.

At Megunticook, we did all those things as well as asking wealthy potential donors directly for help. Coach Hills said one of the most important steps was to apply for 501(c)(3) status.

For me, that didn’t happen at the very beginning, but ended up being critical for the fundraising effort,” Hills said. “That nonprofit status took me over two years to get and included several rewrites and a visit with a lawyer who worked pro bono.”

Membership dues are the core income for most clubs. Some programs charge per

program, per season, or in larger programs, a flat fee for a year of rowing. That model works best when the rowing is year-round. Here in Maine, our season, if we are lucky and get an early thaw, goes from late May to the end of October.

There is as much variety in the setups of clubs in Maine as there is in size. Some smaller clubs like Yarmouth and Down East Rowing have no official coach. Larger clubs like Maine Coast Rowing, Megunticook, and PCRA, with rosters of between 30 and 80 members, have experimented over the years with different ways to structure their programs. Depending on funding and coach availability, these teams have had hourly, seasonal, and full-time coaches. At one time, Megunticook even had a head coach/ executive director position.

At Down East, team members take turns teaching Learn to Row classes, and sometimes the club hires coaches like me to spend a week or two in the summer coaching singles on Long Pond, but mostly members are on their own when it comes to figuring out how to improve their stroke. Basically, you do what you need to do to get people on the water, with or without a coach.

If you really want a club to take off, however, you need to have a head coach who’s in charge of daily operations and pay him or her a living wage. How do you do that when you begin? You probably can’t. But over time, as the club becomes more established, if you really want sustainable growth, you need to invest in a full-time coach.

Drew Combs, head coach at Litchfield Hills Rowing Club in Litchfield, Conn., where I went to high school, told me:

“When I started coaching here in 2019, my salary was conditional on growing the program. When I reached certain recruiting goals, the club increased my salary.”

That approach has worked for LHRC. When Combs began, there were 18 masters and 14 youth members and only one athlete had ever gone to youth nationals. Now the team has grown to 30 masters rowers and 55 to 60 youth rowers, with three to four assistant coaches. Last year, 28 rowers went to youth nationals, a crew won at the Charles, and 60 percent of his athletes who graduate go on to row in college.

The right head coach can raise the

income of a program by recruiting. But if a club isn’t willing to pay a reasonable salary, it forces good coaches out because they can’t afford to feed their families.

Rural rowing clubs go through cycles. They’ll have some great years full of high numbers and big wins, and then a coach has to leave, and the cycle begins all over again. That just happened to Maine Coast Rowing. Head Coach Dave Spraker has been there, full time, for the past three years, during which he expanded the youth, rec, and competitive programs. He recently had to leave to help take care of a family member, and now MCRA is starting all over again.

Unlike urban clubs, which have a greater number of potential coaches from which to draw, a rural club that loses a coach may have to hire someone from another state. Now we’re back to the competitive-salary conversation. What is competitive in Maine might seem pretty low to someone from a big city.

It’s the chicken and the egg cliché. You need a great coach to grow the program, but how do you afford the great coach if you don’t have the income?

Where I now coach at PCRA, we are rebuilding after a slow down cycle that began when a 2018 storm wrecked all our boats and that continued through Covid. Our situation is unique because we wetlaunch into Casco Bay and can row only at high tide in the mornings.

Before the boat disaster, the team had an agreement with a local CrossFit gym. We provided ergs that we used in the morning. In exchange, the gym used them the rest of the day. That meant that on “off the water” days, the team could still work out together. For a few years, we competed in races, but after 2020, the club nearly folded, and we’ve been rebuilding since.

LHRC Coach Combs says sustainable growth comes when you make a plan. Plan your recruiting a year in advance. Try programs out. If they don’t work, pivot and try something else.

Litchfield invested a lot of time and money in its annual Learn to Row Day but failed to retain many people More successful were free days when middle-school kids could come and row in the barge, followed by three more free days of rowing for those same kids.

“If you’re not growing, your dying,” Combs said.

The middle-school rowers are great feeders for the high-school program. But

what happens when you exhaust one school? You make a plan with a different school. Talk to the athletic director and get her on your side and feeding you students. Then move on to the next school. You might have four high schools within a 30-minute drive of the club, and when you have a community program, you can draw from all of them.

Ry Hills, founder of Megunticook Rowing, left “Club” out of the name purposely.

“I want to take the exclusivity out of rowing,” he explained.

Hills wants people from all walks of life to enjoy our beloved sport.

The proliferation of clubs around the world has allowed rowers to get on the water wherever they are.

Amy Dyer, who rows with LHRC, told me she recently planned a vacation on Cape Cod, found Cape Cod Rowing, and called ahead and let the club know she was coming and what her skill level was.

“I feel like rowing is an international language no matter where you go,” Dyer said.

If you’re going on vacation to Australia, as one of our PCRA members did last winter, you can row for a day or two Down Under, and they’ll be happy to have you. You may have nothing else in common with someone, but if you’re both rowers, you belong to the same tribe and speak the same language.

Whatever the size of your club, clear goals and careful planning are keys to success. All clubs begin with one person thinking, “Wouldn’t it be nice to have a rowing club here.”

How those clubs grow depends on many factors—where they’re located, how many experienced rowers live in the area, how much money can be raised.

But if there’s enough passion, it will happen.

AMY WILTON, who lives in Portland, Maine, is a professional photographer and rowing coach. Her photography business (www.amywiltonphotography. com) ranges from portraits and weddings to website rebranding and, of course, rowing. She has coached high-school, club, and college athletes and coaches currently at Portland Community Rowing Association. She does weekend and week-long coaching visits to clubs by request

THE CANADIAN OLYMPIC COACH SET OUT TO BE A PSYCHOLOGIST AND FELL INTO COACHING ROWING ACCIDENTALLY. TODAY’S ATHLETES, HE SAYS, ARE WELLINFORMED AND SUPER PROTECTIVE OF THEIR TIME.

BY CHIP DAVIS

Canadian Olympic coach Tom Morris is one of the most successful rowing coaches in North America, having led the Canadian lightweight double to the Olympic silver medal in Rio in 2016 and then the Canadian women’s eight to silver in Paris in 2024.

In between, he coached the German women’s national squad while Canadian Olympic rowing went through a period that an independent investigation later called “toxic” and that led to the dismissal of the head women’s coach in 2021, just five months before the Tokyo Games.

Michelle Darvill stepped in and saved the day, coaching the eight to Olympic gold, and was hired away promptly by The Netherlands. Morris, a native of Australia, returned to Canada and is now national women’s lead coach at Rowing Canada Aviron.

Rowing News: Is it true that you never set out to be a coach?

The coaching was by accident. My intention was to be a psychologist. The plan was to go into sport and educational psychology, with a focus on human learning theory. But the coaching…I couldn’t believe it became a job, really.

I sort of fell into it. I just loved doing it. I volunteered, and became paid, then became part-time, and became full-time.”

Rowing News: What’s different now from your first go coaching Canadian Olympic rowing?

The biggest difference is that the athletes have evolved. They are the most informed generation of athletes we’ve ever had, and their time is precious, more so than in the past.

As coaches, you’re custodians of their time. They buy into you, they give you their time, and in response you have to make sure you don’t waste it.

They’re far more protective of their time now than they used to be. I don’t know if that’s a post-Covid thing or if that’s just the way sport is going in general, but I’ve definitely noticed it. You have to be more thorough. We have to be less arbitrary. We have to make sure that everything we do has a real strong purpose and connection to what the objectives are. Otherwise, it’s just not worth doing.

Canada has gone through a bit of an understanding of itself in terms of what value is placed on winning well. And in the process of going to SafeSport and safeguarding, there was a bit of an

adaptation phase. Now, everyone has a pretty good understanding of where they are. Nothing really changed in the athletes. They still want to be pushed; athletes still want to be driven by the coaches. They want to be supported, they want to be challenged, and they want to achieve success, so none of that has changed. It’s just some of the actions and behaviors that led to that previously are different from the actions and behaviors that lead to that now.

Rowing News: You’re a true North American coach in that you were courageous enough this spring to take your crew down to race—and lose handily to—both the University of Texas and Stanford, two of the fastest women’s eights in North America. You also went to the Royal Canadian Henley Regatta with elite crews, and won. Do you have a different approach as an elite coach?

One hundred percent. It’s better to learn the lessons early than to learn them late. We took our crew to Texas, primarily made up of scullers thinking “Should I try sweeping?” and some new athletes. There had always been this mindset that the eight was a softer event. And I’m of the firm belief that the top NCAA eights can match up with senior [world-

championship] eights.

So why wouldn’t we, when Dave [O’Neill, Texas head coach] was kind enough to give us an invitation, take that opportunity to learn some honest truths about where we are, where we need to go, and what we need to build if we’re serious about sustaining any legacy in the women’s eight internationally?

We have a new cohort of athletes, they’re pretty untested, and we thought, “Why not expose them to this?” I’m big on that. You either race with a fear of losing or you race with a sense of the opportunity that exists in every race. One of our things we say is that before anyone is a gold medalist, they’re not a gold medalist, so what are you going to do between point A and point B to make the gold medal a reality?

Rowing News: What should we expect in Shanghai at the 2025 World Rowing Championships?

We don’t have any expectations of ourselves other than to put down performances that reflect what we’ve been doing in our training. We’d be remiss to put outcome-based targets on ourselves, because it’s a new year, we’re going to China, and almost half our group has never rowed on the senior [world championship] level before.

It’s exciting for me. The coaching successes I’ve been a part of have always come relatively late. This is the first time we’ve actually been able to start a quadrennial with the intention of seeing it through a four-year plan and watching it come to fruition.

The way Shanghai sits for us is just a regatta to establish a high level of learning, just like we did with Texas and just like we did in St. Catharines [at Canadian Henley]. Right now, we really are happy with the athletes, their attitude, the culture, that grit that they bring to training, their attention to detail, and we’re looking forward to being challenged. But really we’re going to Shanghai to race ourselves.

2-layer neck gaiters will protect you throughout the seasons. Stretchguard fabric with extreme 4-way stretch for optimal comfort. Super soft, silky feel that is lightweight and breathable. 100% performance fabric, washable and reusable.

$20

ALL AVAILABLE WITH YOUR TEAM LOGO AT NO EXTRA CHARGE (MINIMUM 12)

UNITED STATES ROWING UV

VAPOR LONG SLEEVE $40

WHITE/OARLOCK ON BACK

NAVY/CROSSED OARS ON BACK

RED/CROSSED OARS ON BACK

PERFORMANCE LONG SLEEVES

PERFORMANCE T-SHIRTS

PERFORMANCE TANKS

Order any 12 performance shirts, hooded sweatshirts, or sweatpants and email your logo to teamorders@rowingcatalog.com and get your items with your logo at no additional cost!

Head races require a different level of physical exertion and fatigue tolerance over a longer period of time. The ideal is to find your flow—a level of exertion that feels fast but easy.

Autumn is the exciting time of head races, which have their own unique rules and challenges. They come in a variety of formats and are contested on different courses over different distances.

Featuring individual boats starting at set intervals and racing against the clock, head races require rowers, and especially coxswains, to possess skills and qualities that are completely different from those exercised in side-by-side races.

Consequently, you have to prepare specifically for this type of race, beginning with physiological conditioning, since these races are significantly longer than sprint races and therefore require endurance above all else.

The energy supply for a long-distance race is approximately 95 percent aerobic and five percent anaerobic. Although the anaerobic component is important at the

beginning and end of the race, as well as when a rival boat needs to be overtaken quickly, and although sometimes it can determine the outcome, the aerobic component is more essential for success.

The second most important factor in a head race is the ability to steer the fastest route to the finish line. This begins with knowing the course by studying it on a map and identifying crucial sections and features—turns, bridges, buoys, obstacles. Seek out someone who knows the course from experience and can give you advice and pointers. Also, try to row the course before the regatta to gain familiarity. Note landmarks that will help you plot when to begin steering, where to steer, and how far you’ve come.

Then there’s race strategy, which begins with the optimal approach to expending your energy throughout the race (explained in detail in my new book,

Rowing Science). In short, you should start five to 10 strokes before the actual starting line. Race organizers usually give you the necessary leeway to line up at the start and accelerate toward the starting line. The key is to reach the starting line exactly at the middle of your race pace, not at the highest possible speed.

You then use up your high-energy phosphates for a short 10-stroke sprint before switching to your race pace—the fastest pace you can maintain for most of the distance. It’s important to transition slowly from the fastest speed achieved in the 10 starting strokes to race pace to make the most of the speed gained.

You also need to produce some lactate, which kick-starts your cardiovascular system for peak performance. The trick is to avoid accumulating too much lactate while finding the most efficient stroke rate for your race pace. I call this “red-lining,”

where you push the limits of your aerobic system without accumulating too much lactate.

Intrinsic to this approach is finding your best stroke rate. Too low a rate requires a higher force output, which tends to produce more lactate. Too high a rate can lead to technical deficiencies because you either shorten your stroke length, making propulsion less efficient, or you rush your recovery, interrupting your flow and reducing the recovery time your body needs. In training, you need to find the right mix of stroke rate, stroke length, and force output; it should feel fast but sustainable.

The final step is to hit the right finishing sprint. This shouldn’t occur over a long distance or by significantly increasing your speed; actually, if you can do that, you went too slow up to that point. Depending on your experience and fitness level, the sprint could be as little as 200 to 400 meters or 20 to 40 strokes. Break it into smaller chunks of seven strokes, increasing your effort and stroke rate with each interval.

Setting the correct rigging is also important and is based on your training, wind and water conditions, and expected pace changes in the turns and when overtaking competitors starting directly in front of you. If you expect pace changes, you should lighten your rigging a bit.

Last but hardly least is mental preparation. Be prepared for commotion in the starting area. Some boats may not follow the traffic rules; others may cause distraction and anxiety. You may be subjected to unwelcome jolts from your opponents before the race even begins.

A head race also requires a different level of physical exertion and fatigue tolerance over a longer period of time. The ideal is to find your flow—a level of exertion that feels fast but easy, focuses your mind on the immediate moment, and allows you to perform confidently and well. This requires full concentration on the task at hand.

Head races can be exciting and fun, and by emphasizing long-distance training and perfect technical rowing, excellent preparation for next spring’s sprint races.

Wisdom and experience give you the self-sustaining confidence you need when things get tough. Don’t be afraid to take chances or make mistakes.

The role of coxswain comes with great responsibility, and with that responsibility comes great pressure. We are not supposed to let on when we feel it but inevitably we will.

What do you do when you aren’t feeling your most confident, when the seeds of doubt creep in and you question whether you’re capable of doing the job?

First, remember that everyone goes through periods of self-doubt.

“I always had self-doubt,” said 2004 Olympic champion coxswain Pete Cipollone, who also won three world championships in the late ’90s, a silver (2003) and a bronze (2002) in the eight as well as worlds gold (1995) and silver (1994) in the coxed four. “It is an essential motivator.”

The way to head off these moments is to begin learning as much as you can about the sport and to keep learning. Knowledge is power, and that knowledge gives you the basis for acting. Sometimes the action you take leads to success, sometimes to less-than-desired outcomes, but it’s always a learning experience, and that learning experience leads to wisdom.

“My confidence was highest when

I knew I had done everything in my control to prepare,” Cipollone said. “This meant practice, practice, practice—not until I got it right, but until I could not get it wrong.”

Wisdom and experience give you the self-sustaining confidence you need when things get tough. Don’t be afraid to take chances or make mistakes.

“I learned to embrace the notion that the first step to being great at something is being bad at it—and doing it anyway,” Cipollone said.

If you are unsure, turn to a trusted coach, coxswain, or other mentor for advice.

“Early in my career, Coach [Mike] Teti told me, ‘It’s only a mistake if you make it twice.’ It was one of the most important pieces of coaching I ever got.”

Ask questions and think through the answers carefully. Stay positive and know you’ll have ups and downs. Just remember to keep your bow pointed in the right direction.

GEORGE KIRSCHBAUM, author of the Down and Dirty Guide to Coxing, is a coach and a member of the USRowing Safety Committee, serving as the Mid-Atlantic representative. When not advocating for safety, he can be found championing the building of a boathouse in Arlington, Va. He can be reached at george@ thecoxguide.com

If varsity rowing isn’t your path, it’s not the end of your rowing journey. Many universities have competitive club programs that offer meaningful athletic and social experiences.

It’s not uncommon for high-school seniors to feel anxious about recruiting. Maybe you’ve dreamed of rowing at a varsity level program, but after sending dozens of emails, the responses have been limited— or worse, nonexistent. Perhaps you were in touch with several schools and, suddenly, the communication has gone silent. The questions naturally follow: Did they forget about me? Are they no longer interested but didn’t say so?

The good news is that you still have options, even as a senior.

1. Apply Anyway

Sometimes coaches may hesitate to pursue an athlete because they’re uncertain about admissions. If you’re truly interested in a school, it can be worthwhile to apply regardless. Once admitted, you can reach out again with a fresh update:

“Coach, I wanted to let you know that I’ve just been admitted to your university and would love the chance to learn more about opportunities to walk on to your team.”

Admission can change the conversation significantly,

2. Broaden Your Outreach

If one coach isn’t responding, consider copying others on the staff in your emails. Every coach sees athletes differently, and sometimes another set of eyes on your profile can spark interest and reopen communication. You have nothing to lose by casting a slightly wider net.

3. Pick Up the Phone

Yes — the “cold call” still has value. Call the coach’s office during working hours. If no one answers, leave a short, professional voicemail. Introduce yourself, state your interest, and ask for a convenient time to talk. Direct contact can sometimes get attention when emails don’t.

4. Seek Guidance

If you’ve tried multiple approaches without success, it may be time to consult with your current coach, a trusted mentor, or a recruiting expert who can evaluate your situation and help refine your strategy.

5. Explore Alternatives

If varsity rowing isn’t the path forward, it doesn’t mean the end of your rowing journey. Many universities—including top academic institutions—have competitive club programs that offer meaningful athletic and social experiences. For countless athletes, these programs provide a fulfilling balance of academics and rowing.

The recruiting process can feel uncertain, but you have more options than you may realize. Whether through persistence, strategy, or finding the right environment, there is a place for you to continue your rowing journey.

Our state of poor health is not because we consume sugar and our diets are unhealthy. Physical inactivity reduces our ability to metabolize sugar optimally.

I’ve cut out sugar. Gurus on social media say it’s fattening, a waste of calories, and toxic.

I have a sweet tooth. Given the choice of eating more dinner or having dessert, I’ll always choose dessert!

Is Coke healthier if made with cane sugar instead of high-fructose corn syrup?

If you’re like most of my clients, you’re confused about the role of sugar in your daily sports diet. The antisugar “experts” (who speak to the general public, not specifically to athletes) argue that sugar is health-erosive. Sports nutrition researchers claim sugar enhances performance. So for athletes, is sugar friend or foe?

Sugar: Avoid it!

• Limiting sugar intake does not harm anyone. Sugar is not an essential nutrient. Our bodies can make sugar (glucose) by breaking down muscle and fat tissue or by converting the fat and protein we eat into glucose.

• The average American consumes about 17 teaspoons of added sugar a day (60 pounds a year). That’s a lot of empty calories. Populations with a high intake of added sugars tend to have health issues. By reducing added sugar to less than 10 percent of total calories, they can reduce tooth decay and the risk of weight gain, obesity, and associated health issues.

• Dietary sugar can drive up blood sugar. The risk of diabetes increases by 38 percent in those who routinely consume the sugar equivalent of a can of soda a day.

• Drinking Coca-Cola made with

cane sugar is no better for you than CocaCola made with high-fructose corn syrup.

Cane sugar (also called sucrose) is comprised of 50 percent glucose, 50 percent fructose. High-fructose corn syrup is 45 percent glucose, 55 percent fructose. Both are metabolized similarly. Although President Trump says all-natural cane sugar “is just better,” science does not support that belief. Both contribute to health problems. Drinking Coke made with cane sugar will not make America healthier.

• With very high sugar consumption (sports drinks, gels, soda, candy), one could become nutrient-depleted. Emptycalorie sugar offers no nutritional value yet displaces nourishing food, which can lead to a lackluster sports diet.

Sugar and rowers: Moderation!

• Sugar consumption increased from less than 10 pounds per person a year in the late 1800s to about 100 pounds per person a year by 1945. It remained relatively flat until 1980. Yet our health improved between 1880 and 1980. We can’t blame just sugar for health problems. Lack of exercise, high stress, and poverty are also health-erosive.

• Sugar (a “carb”) is in breast milk, dairy food, fruit, vegetables, honey, potatoes, corn, quinoa, and all grains. People around the globe have consumed these foods for years. So why now are sugar and “carbs” deemed responsible for creating human obesity and diseases?

• Such fear-mongering terms as unhealthy, poisonous, and toxic are simply unscientific. People who lack knowledge

of physiology fail to understand that sugar is not inherently fattening, nor is one particular food inherently healthy or unhealthy. An apple is a healthy food; a diet of all apples is very unhealthy.

• Our present state of poor health is not because we consume sugar and our diets are unhealthy. Rather, we are physically inactive. Too little exercise reduces our ability to metabolize sugar optimally. That, along with environmental factors, endocrine disrupters, stress, etc., explain the fundamental causes of obesity and metabolic disease.

• In terms of diabetes prevention, you should be concerned about blood sugar, not dietary sugar. A rise in blood sugar that occurs after eating is not pathological— unless unfit muscles and the liver fail to take up the sugar. It’s not what you eat, but what your body does with what you eat.

With inactivity, the body becomes less able to transport sugar out of blood and into muscle. This erodes metabolic health. Also with inactivity, a person can easily overeat because energy intake gets dissociated from energy expenditure.

Remember: The bodies of athletes are metabolically very different from the bodies of the sedentary. You want to stay active to preserve your ability to enjoy some sweets without hurting your health.

• Sugar cravings happen when the body needs fuel. If you eat before you run out of fuel, you will tame your sweet tooth. Have a second lunch when you are droopy and low on energy in the afternoon instead of devouring sweets in the evening. That said,

a desire for sweets can also be a genetic preference.

Concluding comments

Lack of physical activity is a bigger threat to health than sugar. For people who are overfat and underfit, a diet low in sugar and starch is likely a wise idea. But for athletic people like rowers (who are at lower risk for heart disease, diabetes, and obesity), sugar and carbs are not toxic; they are an important fuel for enhancing athletic performance.

The one-size diet does not fit all. No one is suggesting that athletes should eat more sugar. Instead, rowers can embrace a sports diet that includes an appropriate balance of sugars and starches (carbohydrates) in each meal. Strive for a healthy eating pattern that offers 85 percent to 90 percent quality foods and 10 percent to 15 percent fun foods, such as apple pie instead of an apple.

If you are fearful sugar will harm your health, keep in mind that fearmongering relies on cherry-picked research that can prove what the “expert” wants to prove. Fear-mongering “experts” have created distrust of the food industry and have shaped opinions that support raw foods, super foods, whole foods, organic foods, and clean eating. Confusion reigns!

My suggestions:

—Enjoy a variety of foods to get a variety of nutrients.

—Limit added sugar to less than 10 percent of your total calories (about 250 sugar calories per day for an active woman; 300 sugar calories for an active man).

—If you currently limit your sugar intake to a weekly “cheat day,” try this experiment: Enjoy a small sweet daily as a part of lunch or afternoon snack. This can curb your urge to binge on sweets in an unhealthy way on a cheat day. Sugar binges are what give sugar a bad name.

Train for event-specific conditions. Besides endurance work and distance trials, be prepared for the climate in which you’re racing, especially if it’s different from the one at home.

Jitters the morning of a race are a positive signal that you are ready for a challenge. How the rowing universe decides to test you over a given course is unpredictable. It can tangle your rudder ropes to complicate your steering or give

It can take several hours for your body to recover from the dehydration you can experience on an airplane.

your boat some extra oomph to cruise past a crew you’ve been chasing all season. Prepare for your events well before you get to the course.

Train for event-specific conditions. In addition to the right endurance work and distance trials, be prepared for the climate in which you’re racing, especially if it’s different from the one at home. If a warmer location, do some rows during a hotter part of the day; if a cold location, make sure to have warm clothes, especially for head and hands. Before you travel, make a list of everything you plan to bring and plan for nasty weather as well.

Know the course. Study the twists and

turns of the race route and row workouts that include similar turns. Commit the image of the map to memory and design your race plan with words or moves that will help you stay in the moment. Row over the course before the race to identify landmarks.

Train your eating. Experiment with prerow meals or snacks. Once you establish what works for you, stick with that on race day, too. If you race at an unusual time of day, use some weekends to simulate your actual race day and develop an eating/ warm-up plan.

Arrive early; don’t crowd your day. If you are traveling to a race, it can take several hours for your body to recover from the dehydration you can experience on an airplane. Avoid alcohol and caffeine, drink lots of water, and wear compression socks on the plane.

Consider arriving 48 hours before the start so you have time to adjust and relax. If racing close to home, arrive at least 90 minutes before you launch so you can pick up your number and rig your boat.

MARLENE ROYLE, who won national titles in rowing and sculling, is the author of Tip of the Blade: Notes on Rowing She has coached at Boston University, the Craftsbury Sculling Center, and the Florida Rowing Center. Her Roylerow Performance Training Programs provides coaching for masters rowers. Email Marlene at roylerow@aol.com or visit www.roylerow.com.

It isn’t something to be feared but rather embraced as a fact of life and an opportunity to reinforce positive culture and jump-start change.

Turnover. It’s an inevitable fact of coaching any sport at any level. Assistant coaches move on to bigger roles. Head coaches advance to higher-profile teams. Graduate assistant coaches, well, graduate.

According to the 2025 Salary Survey of the Intercollegiate Rowing Coaches Association, the average tenure of an associate head coach/first heavyweight assistant coach ranges from three to five years. For second assistant coaches, just two to three years. That makes for a lot of movement each year. Turnover isn’t something to be feared but rather understood as a fact of life and embraced for the opportunities it presents. For the coaches just now settling into a new role or those adjusting to new members of their staffs, there’s a real opportunity to hit the ground running, reinforce positive culture, or jump-start changes to get things moving in the right direction.

If done well.

This is a common topic of discussion among coaches I work with in my leadership coaching practice as well as younger coaches I mentor as they take the first steps in their professional coaching careers. One head coach I work with cited hiring his new assistant coach as the single biggest decision he had to make this summer. He had to fill the gap left by a much beloved assistant who had moved on to lead his own program and ran a real risk of losing team buy-in and setting back the advances the team had made in the past year, from both a performance and culture standpoint. He was right to take this decision very seriously. Often, though, the focus is squarely

on the actual hiring process—finding the right assistant coach or the right next job—and the next steps get overlooked. But the reality is that the real hard ongoing work comes after that. And that’s where the biggest opportunity for positive growth exists.

Building trust and getting into a collective rhythm take time. Finding your footing as the new coach in town or figuring out how to rebuild the structures of a high-functioning staff takes focus and flexibility. A few good practices can help everyone get off on the right foot and begin building momentum.

The first step is to establish roles early. Clear responsibilities reduce unnecessary friction and allow everyone to focus their limited attention on what matters most. Ambiguity around who handles inbound recruit emails or orders lunch while the team is traveling will just lead to frustration. (But don’t overlook the need for flexibility to allow for coaches to do

work that they are especially skilled at or interested in when the time comes.)

Next, create early wins together. As with a crew or across a whole team, trust isn’t created in one grand moment. Instead, it is hard won through an accumulation of small wins. Having opportunities to get some wins individually and as a staff, and to have those wins acknowledged publicly and celebrated, go a long way toward building confidence in each other’s competence.

Finally, communication, and especially listening, need to be prioritized. New coaches should approach a situation with curiosity and humility. Yes, sometimes things are going to be done differently here. Give it a try and see how it goes, remaining open to the idea that this may be a better way to run things or an opportunity for you to offer a respectful suggestion.

Returning coaches can model the same by being open to fresh ideas and asking for contributions. The best staffs I’ve

been a part of were those where everyone had an opportunity for input that was taken seriously. Of course, it can never all be implemented, but the best ideas and the most satisfaction come from a staff that is open-minded and valued. And it’s simply more fun to work with people you like, trust, and value—and who have the same attitude toward you.

Turnover is going to happen. But if you approach it not as a disruption but as an opportunity, you can strengthen culture and performance. Just like athletes adjusting to new lineups, coaches who embrace transition with a clear vision and trust in each other will be the ones whose teams move fastest in the long run.

ADVERTISERS INDEX

Nathan Benderson Park 24 Nielsen-Kellerman 5

Peinert Boatworks 10

Peterson Architects 28 Pocock Racing Shells 8..9

RegattaSport 16 Robbie Consulting 28 RowAmerica 22..23

San Diego Crew Classic 56

Shimano North America 15 SportGraphics 12..13 The Conference 64 Vespoli USA 68

DOCTOR ROWING CON’T FROM PAGE 66 >>>

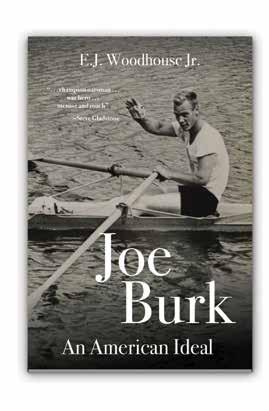

time and time again they talk about Burk as a revered father figure. Even when moved from the varsity to the JV, his oarsmen mention his fairness and the care he showed them,” Woodhouse said.

When the weather was raw and cold in Philadelphia, Burk would jump off the dock into the Schuylkill to demonstrate that it was safe to go out on the water. That toughness and his war record inspired a number of his men to serve in a different, controversial type of war, Vietnam.

Woodhouse has done an impressive amount of research to track down some of the ideas that inspired Burk. In the ’60s, a New Zealand running coach named Arthur Lydiard had pushed his athletes to great heights. At the 1964 Olympics, Peter Snell had won double golds in the 800 and 1,500 meters. Lydiard advocated a regimen of high mileage at moderate pace and introduced the idea of periodization in athletic training, a cornerstone of today’s training methods.

the Penn/Harvard rivalry. Harry Parker, the Harvard coach, had rowed for Burk at Penn. When Parker launched his own sculling career, he worked with Burk. The result was that Parker represented the USA at the Rome Olympics in 1960.

Their rivalry as coaches peaked at the 1968 Olympic trials when the two crews went stroke for stroke down the 2,000-meter course. In the photo finish, Harvard was proclaimed victor by five onehundredths of a second. Ever gracious, Joe Burk congratulated his protege.

I visited Joe Burk and his wife, Kay, at their retirement cabin in Montana and can confirm that meeting them was an uplifting experience. Woodhouse quotes Nick Paumgarten, longtime head of the Friends of Pennsylvania Rowing, who summed up the modern view of Burk, calling him a total gentleman, a gracious loser, and a great winner.

DOCTOR ROWING, a.k.a. Andy Anderson, has been coxing, coaching, and sculling for 55 years. When not writing, coaching, or thinking about rowing, he teaches at Groton School and considers the fact that all three of his children rowed and coxed—and none played lacrosse—his single greatest success. Active Tools 17 Bont Rowing 4 Concept2,

At Penn, Burk adopted Lydiard’s approach. For anyone who is interested in the history of training and how it intersected with race results, Woodhouse has unearthed some great stuff. In the fall of 1966, Penn was rowing 18 miles every day, and 24 on Saturday.

There is also lots of great stuff about

It gives me great pleasure to recommend Ed Woodhouse’s book. He will be at the Heads of the Charles and Schuylkill selling, autographing, and talking about this wonderful man, Joe Burk.

ANDY ANDERSON

Despite losing the singles trials for the 1936 Berlin Olympics to a fellow Penn AC sculler, Joe Burk did not sulk. He went back to the family farm, got back in his single, and rowed his own style with his own strategy.

Last month, Dotty Brown alerted our readers to Ed Woodhouse’s biography of Joe Burk, the great sculler who later became the head coach at the University of Pennsylvania and was so influential for generations of oarsmen.

What prompted a Harvard oarsman to write a biography of a Penn coach? Woodhouse was part of the legendary Rude and Smooth crews of the 1970s. Why had he cast his eyes away from the Charles? Had he forgotten his own coach, Harry Parker?

“I am very taken with the idea of mentors,” Woodhouse told me. Scratch any rower and he’ll tell you who helped him rise.

“I started seeing how so many of the people I learned about were connected. You can draw a line from George Pocock to Rusty Callow, Burk’s coach at Penn, to Burk to Harry Parker, my coach.”

“If what you’re doing makes you go fast, do it.”

— George Pocock