22-24 October 2025

22-24 October 2025

Wednesday 22 October, 7.30pm Holy Trinity Church, St Andrews

Thursday 23 October, 7.30pm The Queen's Hall, Edinburgh

Friday 24 October, 7.30pm City Halls, Glasgow

STRAUSS Suite in B-flat Op.4

HARTMANN Concerto funebre

Interval of 20 minutes

HAYDN Symphony No.103 in E-flat ‘Drum Roll’

Alina Ibragimova violin/director

Alina Ibragimova

4 Royal Terrace, Edinburgh EH7 5AB

+44 (0)131 557 6800 | info@sco.org.uk | sco.org.uk The Scottish Chamber Orchestra is a charity registered in Scotland No. SC015039. Company registration No. SC075079.

THANK YOU

Our Principal Conductor’s Circle are a special part of our musical family. Their commitment and generosity benefit us all – musicians, audiences and creative learning participants alike.

Annual Fund

James and Patricia Cook

Visiting Artists Fund

Harry and Carol Nimmo

Anne and Matthew Richards

International Touring Fund

Gavin and Kate Gemmell

Creative Learning Fund

Sabine and Brian Thomson

Conductor Emeritus Joseph Swensen

Donald and Louise MacDonald

Chorus Director Gregory Batsleer

Anne McFarlane

Principal Second Violin

Marcus Barcham Stevens

Jo and Alison Elliot

Second Violin Rachel Smith

J Douglas Home

Principal Viola Max Mandel

Ken Barker and Martha Vail Barker

Viola Brian Schiele

Christine Lessels

Viola Steve King

Sir Ewan and Lady Brown

Principal Cello Philip Higham

The Thomas Family

Sub-Principal Cello Su-a Lee

Ronald and Stella Bowie

Cello Donald Gillan

Professor Sue Lightman

American Development Fund

Erik Lars Hansen and Vanessa C L Chang

Productions Fund

Anne, Tom and Natalie Usher

Bill and Celia Carman

Scottish Touring Fund

Eriadne and George Mackintosh

Claire and Anthony Tait

Cello Eric de Wit

Jasmine Macquaker Charitable Fund

Principal Flute André Cebrián

Claire and Mark Urquhart

Principal Oboe

The Hedley Gordon Wright Charitable Trust

Sub-Principal Oboe Katherine Bryer

Ulrike and Mark Wilson

Principal Clarinet Maximiliano Martín

Stuart and Alison Paul

Principal Bassoon Cerys Ambrose-Evans

Claire and Anthony Tait

Sub-Principal Bassoon Alison Green

George Rubienski

Principal Horn Kenneth Henderson

Caroline Hahn and Richard Neville-Towle

Principal Timpani Louise Lewis Goodwin

Geoff and Mary Ball

Diamond

The Cockaigne Fund

Malcolm and Avril Gourlay

John and Jane Griffiths

James and Felicity Ivory

George Ritchie

Tom and Natalie Usher

Platinum

E.C. Benton

Michael and Simone Bird

Silvia and Andrew Brown

David Caldwell in memory of Ann

Dr Peter Williamson and Ms Margaret Duffy

Judith and David Halkerston

David and Elizabeth Hudson

Helen B Jackson

Dr and Mrs Peter Jackson

Dr Daniel Lamont

Graham and Elma Leisk

Professor and Mrs Ludlam

Chris and Gill Masters

Duncan and Una McGhie

Anne-Marie McQueen

James F Muirhead

Robin and Catherine Parbrook

Patrick and Susan Prenter

Mr and Mrs J Reid

Martin and Mairi Ritchie

Hilary E Ross

Elaine Ross

Sir Muir and Lady Russell

Jill and Brian Sandford

Michael and Elizabeth Sudlow

Robert and Elizabeth Turcan

Alan and Sue Warner

Anny and Bobby White

Robert Mackay and Philip Whitley

Finlay and Lynn Williamson

Ruth Woodburn

Gold

Peter Armit

Adam Gaines and Joanna Baker

John and Maggie Bolton

Elizabeth Brittin

Kate Calder

James Wastle and Glenn Craig

Jo and Christine Danbolt

James and Caroline Denison-Pender

Andrew and Kirsty Desson

David and Sheila Ferrier

Chris and Claire Fletcher

James Friend

Iain Gow

Margaret Green

Christopher and Kathleen Haddow

Catherine Johnstone

Julie and Julian Keanie

Gordon Kirk

Janey and Barrie Lambie

Mike and Karen Mair

Roy and Svend McEwan-Brown

John and Liz Murphy

Tom Pate

Maggie Peatfield

Sarah and Spiro Phanos

Charles Platt

Alison and Stephen Rawles

Andrew Robinson

Olivia Robinson

Anne McAlister and Philip Sawyer

Irene Smith

Dr Jonathan Smithers

Ian S Swanson

Ian and Janet Szymanski

John-Paul and Joanna Temperley

Douglas and Sandra Tweddl

Bill Welsh

Catherine Wilson

Neil and Philippa Woodcock

Silver

Roy Alexander

Fiona and Neil Ballantyne

The Batsleer Family

Jack Bogle

Jane Borland

Alan Borthwick

Dinah Bourne

Michael and Jane Boyle

Mary Brady

John Brownlie

Laura Buist

Robert Burns

Sheila Colvin

Lorn and Camilla Cowie

Adam and Lesley Cumming

Dr Wilma Dickson

Seona Reid and Cordelia Ditton

Sylvia Dow

Colin Duncan in memory of Norma Moore

Raymond Ellis

Dr and Mrs Alan Falconer

Sheila Ferguson

Dr William Irvine Fortescue

Dr David Grant

Anne Grindley

Andrew Hadden

J Martin Haldane

Ronnie and Ann Hanna

Roderick Hart

Norman Hazelton

Ron and Evelynne Hill

Philip Holman

Clephane Hume

Tim and Anna Ingold

David and Pamela Jenkins

Margaret Mortimer and Ken Jobling

Ross D. Johnstone

Professor Christopher and Mrs Alison Kelnar

Dr Ian Laing

Geoff Lewis

Dorothy A Lunt

Vincent Macaulay

James McClure in memory of Robert Duncan

Ben McCorkell

Lucy McCorkell

Gavin McCrone

Michael McGarvie

Brian Miller

Alistair Montgomerie

Andrew Murchison

Pamela Andrews and Alan Norton

Gilly Ogilvy-Wedderburn

John Peutherer in memory of Audrey Peutherer

James S Potter

Timothy Barnes and Janet Sidaway

Catherine Steel

John and Angela Swales

Takashi and Mikako Taji

C S Weir

Susannah Johnston and Jamie Weir

We are indebted to everyone acknowledged here who gives philanthropic gifts to the SCO of £300 or greater each year, as well as those who prefer to remain anonymous.

We are also incredibly thankful to the many individuals not listed who are kind enough to support the Orchestra financially on a regular or ad hoc basis. Every single donation makes a difference.

Become a regular donor, from as little as £5 a month, by contacting Hannah Wilkinson on 0131 478 8364 or hannah.wilkinson@sco.org.uk.

“…an orchestral sound that seemed to gleam from within.”

HM The King Patron

Donald MacDonald CBE

Life President

Joanna Baker CBE Chair

Gavin Reid LVO

Chief Executive

Maxim Emelyanychev

Principal Conductor

Andrew Manze

Principal Guest Conductor

Joseph Swensen

Conductor Emeritus

Gregory Batsleer

Chorus Director

Jay Capperauld

Associate Composer

Information correct at the time of going to print

First Violin

Alina Ibragimova

Afonso Fesch

Marie Schreer

Fiona Alexander

Aisling O’Dea

Amira Bedrush-McDonald

Sarah Bevan Baker

Catherine James

Second Violin

Marcus Barcham Stevens

Gordon Bragg

Rachel Smith

Wen Wang

Stewart Webster

Kristin Deeken

Viola

Max Mandel

Francesca Gilbert

Elaine Koene

Steve King

Cello

Philip Higham

Su-a Lee

Donald Gillan

Eric de Wit

Bass

Yehor Podkolzin

Jamie Kenny

Flute

André Cebrián

Marta Gómez

Oboe

Miriam Pastor

Katherine Bryer

Clarinet

Maximiliano Martín

William Stafford

Bassoon

Cerys Ambrose-Evans

Alison Green

Contrabassoon

Heather Brown

Philip Higham

Principal Cello

Horn

Kenneth Henderson

Jamie Shield

Gavin Edwards

Harry Johnstone

Trumpet

Peter Franks

Shaun Harrold

Timpani

Louise Lewis Goodwin

R STRAUSS (1864-1949)

Suite in B-flat major, Op.4 (1884)

Praeludium

Romanze

Gavotte

Introduction und Fuge

HARTMANN (1905-1963)

Concerto funebre (1939, revised 1959)

Introduktion: Largo

Adagio

Allegro di molto

Choral: Langsamer Marsch

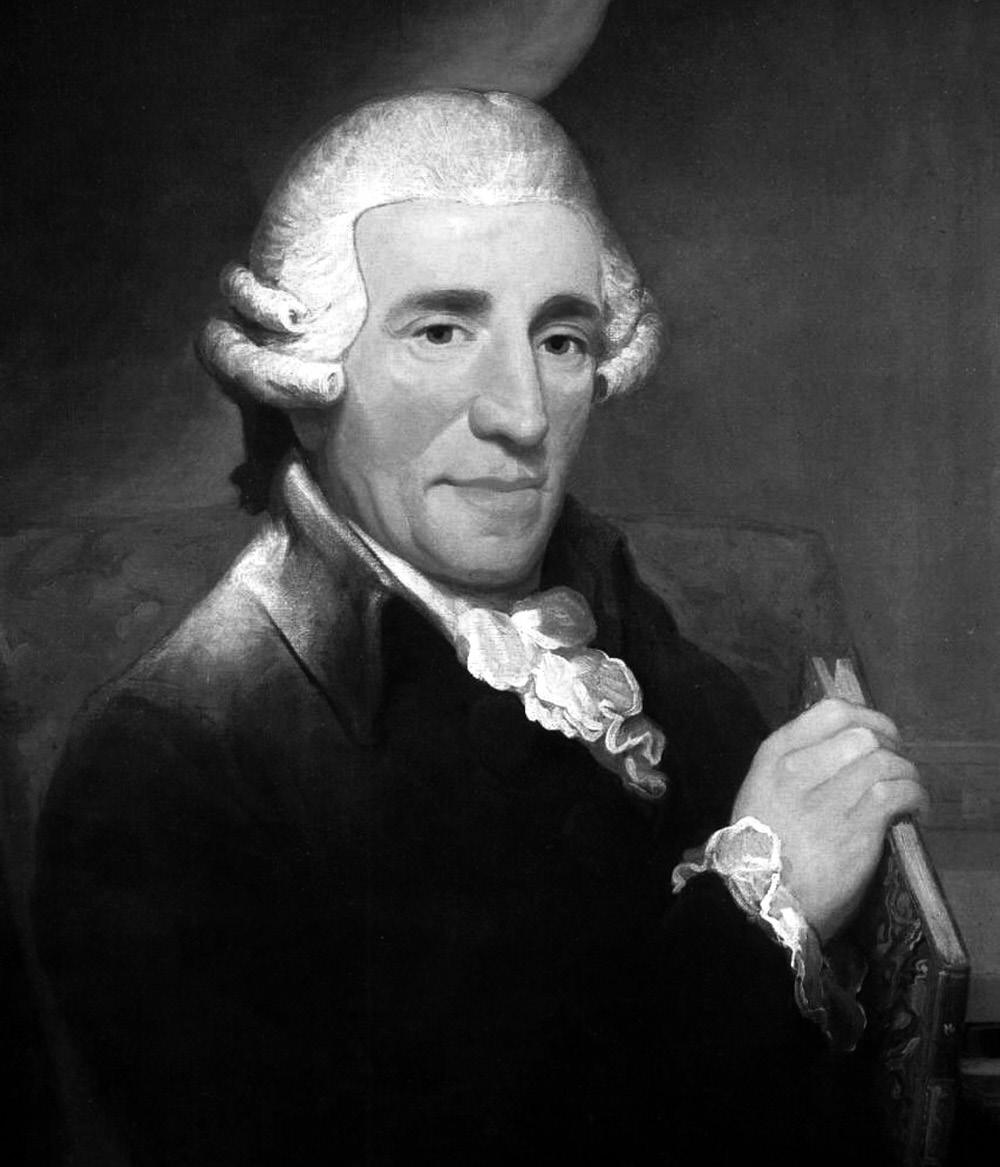

HAYDN (1732-1809)

Symphony No.103 in E-flat ‘Drum Roll’ (1795)

Adagio - Allegro con spirito

Andante più tosto allegretto

Minuet - Trio

Finale: Allegro con spirito

Music exists to charm, delight and entertain, of course. But it also exists to challenge, defy, assert a point of view, give vent to fury or despair. We’ll encounter both of those intents among the high spirits and profound emotions of tonight’s concert, sometimes even mixed up within the same piece of music – from Richard Strauss’ joyful, career-launching Suite in B flat to Haydn’s intentionally crowd-pleasing Symphony No. 103, by way of Hartmann’s deeply moving cry of pain at Second World War atrocities in his Concerto funebre.

We begin, however, more than five decades before that conflict began. Richard Strauss turned 20 in 1884, and he was keen to establish himself as a professional musician. He’d been playing the piano from the age of four and composing since he was six, under the tutelage of some of his native Bavaria’s most accomplished musicians –including his own father Franz Strauss, who was one of the Germany’s most respected instrumentalists as Principal Horn at the Court Opera in Munich.

Three years earlier, the 17-year-old Richard’s single-movement Serenade in E-flat for 13 wind instruments had caught the attention of hugely influential conductor Hans von Bülow, who’d gone so far as programming the piece in a concert with his own Meiningen Court Orchestra, one of the starriest ensembles around at the time. The Serenade went down so well that von Bülow asked Strauss to create something along similar lines specially for the Orchestra, but on a grander scale, and across four movements. The young composer was delighted to oblige.

By the time Strauss set about working on what would become his Suite in B-flat,

The elder Strauss sought actively to steer his son away from the music of Wagner, but the young Richard would discover it anyway – and become deeply intoxicated by it.

he had several major pieces under his belt, including a Violin Concerto, two symphonies, and quite a lot of chamber music. He felt, however, a special affinity for wind music, possibly in part because of his father’s famed role: many of his earliest childhood compositions had been pieces for wind ensemble to be played at home.

Strauss’ father had exerted a profound influence, too, on the kind of music that he was writing. The elder Strauss held notoriously conservative attitudes, barely tolerating the dangerously modernistic creations that had been put together after the holy trinity of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven (well, early Beethoven at least). Schubert, Mendelssohn, Schumann? Perhaps, just about. Wagner? Not a chance: Franz Strauss made no secret of his disdain for Wagner’s music, despite paradoxically playing much of it with

exceptional insight and brilliance in the Meiningen Orchestra.

In short, the elder Strauss sought actively to steer his son away from the music of Wagner, but the young Richard would discover it anyway – and become deeply intoxicated by it. Arguably, it’s that very tension between classical refinement and Wagnerian expressivity that would go on to shape Richard’s musical personality. In terms of his early Serenade and Suite, however, he was only too happy to follow his father’s guidance. Both are closely modelled on Mozart’s Serenade in B flat, K361 (the ‘Gran partita’), down to their ensemble of 13 wind instruments, even if Strauss updates Mozart’s earlier ensemble (comprising pairs of oboes, clarinets, basset horns and bassoons plus four horns and double bass) to the rather more modern grouping of pairs of flutes, oboes,

clarinets and bassoons, plus four horns and contrabassoon or tuba.

If the Suite launched Strauss’ career, however, it was a much as a conductor as it was as a composer. With the premiere set for 18 November 1884 in his home city of Munich, Strauss received notification as late as 22 October that year, via publisher Eugen Spitzweg, that von Bülow felt the young man should conduct the performance himself. The fact that he’d never wielded a baton in public before shouldn’t be an issue, von Bülow felt, since the Meiningen musicians would already be familiar with the music –which would also mean there’d be no need for a rehearsal. It was a huge challenge for the young man, and a huge gamble to accept that challenge. The premiere went so well, however, that von Bülow offered Strauss the position of Assistant Conductor in Meiningen six months later. Strauss would even step into von Bülow’s own shoes the following year, temporarily at least, following the elder musician’s surprise resignation.

A short tribute to Mozart had led to a longer commission, a prestigious conducting opportunity and then a longer-term job. And with the knowledge of the music that Strauss would produce in later decades, it’s not hard to see his early Suite in B-flat as a stepping stone between the more Mozart-indebted Serenade and his richer, more complex mature style. Its good-natured, confident Praeludium has a dense, rhythmically complex opening as the ensemble’s instruments elegantly dovetail their lines, though its outgoing beginning contrasts with its gentler, more plaintive later oboe theme. Strauss’ intricate, subtle scoring often pits several lines of music against each other at the same time, drawing on the distinctive

sonorities of the ensemble’s instruments, and subsides to a peaceful close.

Strauss puts the ensemble’s clarinets in the spotlight in the gentle Romanze, with a cadenza-like solo right at the start and a long-spun melody later on. The Gavotte feels more like a symphonic scherzo than the dance its title implies, its perky music based on a simple idea of three falling notes, heard several times at the very start. Strauss returns to a theme from the earlier Romanze to kick off his closing Introduction and Fugue, and draws in all manner of contrapuntal trickery in the main meat of the movement. After one of the ensemble’s horns (naturally) announces the fugue’s theme, it passes to clarinet, oboe and flute before later piling up on versions of itself, being stretched or compressing to doubleor half-speed, and even being flipped upside down. If Strauss is clearly out to demonstrate his compositional prowess, it’s nonetheless in music that propels the Suite to a joyful, delightful close.

By 1933, the nearly 70-year-old Strauss was one of Germany’s elder musical statesmen, a hugely respected and beloved figure with many of his iconic works – from Also sprach Zarathustra to Ein Heldenleben, Salome to Ariadne auf Naxos – already completed and welcomed warmly into the orchestral and operatic repertoires. It was also the year in which Adolf Hitler seized total control of the country, and the year in which tonight’s next composer, Karl Amadeus Hartmann, began work on his symphonic poem Miserae, an impassioned response to the opening of the Nazis’ first concentration camps, including the one in Dachau, near Munich.

Like Strauss, Hartmann had been born in Munich. He was a musical free spirit,

Hartmann began the Concerto in the summer of 1939, but the music took on a broader significance as the worldchanging events of that autumn unfolded.

alarming his teachers at the Munich Academy with his love for Stravinsky and Bartók, jazz and expressionism, and he retained his profound beliefs in democratic socialism throughout his life. It’s probably fairest to describe Strauss’ relationship with the Nazi regime as somewhat ambiguous: also in 1933, he perhaps ill-advisedly accepted the post of President of the Reich Music Chamber, effectively becoming the highest-ranking musical official in Nazi Germany, and also accepted commissions including an Olympic Hymn for the 1936 Berlin Games, while privately condemning and resisting the regime’s brutality and antisemitism.

Hartmann’s activities during Germany’s Nazi years were far clearer. He remained in the country, but he put himself into what’s been described as ‘inner migration’, withdrawing entirely from musical life, and refusing to

allow any of his music to be performed there. Nonetheless, his fame steadily grew outside Germany: his Miserae, for example, made a profound impact at its premiere in Prague in 1935. More importantly, however, during his years of ‘inner migration’ Hartmann continued to compose. Among his creations from that time was tonight’s Concerto funebre, written for solo violin and string orchestra.

The piece was originally inspired – or provoked, perhaps a better description – by the Nazi annexation of Czechoslovakia’s Sudetenland in 1938. Hartmann began the Concerto in the summer of 1939, but the music took on a broader significance as the world-changing events of that autumn unfolded. He later succinctly explained: ‘this particular time indicates the basic character and reason for my piece.’ It was premiered at St Gallen in neutral Switzerland on

29 February 1940 – remarkably, Hartmann was allowed out of tightly controlled Germany for the performance – under its original title Musik der Trauer (or ‘Music of Mourning’). When Hartmann came to make slight revisions to the piece in 1959, he changed its title to today’s Concerto funebre (literally ‘Funereal Concerto’).

It's the only solo concerto that Hartmann wrote, and it’s been suggested that he chose the violin explicitly for its similarities to the human voice, as if to provide a directness of expression for the feelings of fury, despair and hope that the Concerto so clearly conveys. Assigning specific emotions to music is always fraught, but here, Hartmann himself was clear. He later wrote about the Concerto to his close friend, conductor Hermann Scherchen: ‘I wanted to write down everything I thought and felt, and that resulted in form and melody. The intellectual and spiritual hopelessness of the period are contrasted with an expression of hope in the two chorales in the beginning and at the end.’

The Concerto’s four movements flow into one another (almost) without pauses. A loud, dissonant harmony settles onto a brooding unison at the very start of the brief Introduction, setting the Concerto’s seriousminded tone. When the soloist enters, slowly and quietly, it’s with fragments of the Bohemian Hussite hymn ‘You who are God’s Warriors’, perhaps a direct reference to the Nazi annexation of the Czech Sudetenland in 1938.

From quiet, brooding threat, the mood changes entirely in the second movement Adagio, with loud, frenetic tremolos from the orchestra, and a sudden ascent from the soloist to the very heights of their instrument.

The movement later calms, though the music remains angular and dissonant, and eventually moves into something like a slowmoving dance.

Hartmann’s third movement Allegro di molto is a grotesque scherzo that seems deliberately designed to unsettle with its brutal, driving rhythms, its screaming dissonances and its angular, angry solo violin line – though two interruptions from a mysterious, very quiet theme low in the violin’s range seem to come from another world entirely. It feels as if the movement has run out of energy – or perhaps resistance – in its slow, more mournful conclusion, followed by the Concerto’s only pause, written out precisely in Hartmann’s score.

His final movement is a funeral hymn, based on the popular Russian song ‘Immortal Victims’, commemorating those killed in the 1905 Revolution. That song’s broader significance to all those lost in conflict is clear, but at the same time, Hartmann had little time for the strictures of Soviet-style socialism despite his own progressive beliefs. Against hymn-like music from the orchestra, the soloist weaves a freer expression of grief, later joining the ensemble’s more communal mourning. If the Concerto appears to be closing in a mood of sorrow and resignation, however, then Hartmann’s very final gesture might imply otherwise – perhaps fury, determination and resistance.

The Concerto funebre was one of several wartime pieces that Hartmann revised in 1959. In others, he took pains to remove or tone down their more overt references to the darkness of the Nazi years, as if wanting to stress their more universal resonance, or to minimise the sense of his having

There’s no doubt that Haydn was out to charm and delight his London listeners, as the review acknowledges. But he was also out to prod them gently with some surprising innovations.

witnessed and warned against it. With the Concerto funebre, however, he left the musical substance largely untouched. He later explained what he hoped would be the piece’s legacy for future generations: ‘the threat to art will never be a thing of the past as long as freedom is threatened somewhere. That’s why we want to be vigilant, we want to warn, we want to remember past humiliation, we want to speak out when we recognise totalitarian tendencies anywhere.’

From wartime Germany, we leap back in time a century and a half for tonight’s final, far more joyful piece. By the time he wrote his ‘Drum Roll’ Symphony in 1794-5, Joseph Haydn had spent more than three decades employed in the lavish but rather isolated Eszterháza Palace, in what’s now north-west Hungary, then firmly at the heart of the Habsburg Empire. During those decades,

he’d used the wealthy Esterházy family’s resident musicians to the fullest, virtually inventing the modern symphony and string quartet as musical forms and developing his clean, clear, elegant and mischievously witty musical style across operas, chamber music and plenty more.

But equally, he felt he needed to stretch his wings. In 1790, aged 58, he found his chance. The incoming Prince Anton looked to trim his artistic outgoings, still guaranteeing an ongoing salary for Haydn, but no longer requiring his permanent presence. The composer’s music was already wildly popular among London audiences, and German-born, Londonbased impresario Johann Peter Salomon snapped him up for two visits to England, in 1791-2 and 1794-5. Both went down a storm, so much so that Haydn reportedly even considered settling permanently in the

English capital (and was explicitly invited to do so by King George III, no less).

He hobnobbed with royalty and the aristocracy, was fêted at high-society occasions and even received an honorary doctorate in Oxford (which provided his ‘Oxford’ Symphony, No.92, with its nickname). More importantly, with the six symphonies he composed for his first visit, he got to know just what his London listeners liked. When he returned two years later, he could give it to them all over again with six more ‘London’ symphonies – and plenty more besides. In that respect, Haydn’s second batch of ‘London’ symphonies – Nos 99 to 104 – represents a rare meeting of composer’s and audiences' minds: each knowing the other intimately and out to enjoy that relationship to the fullest.

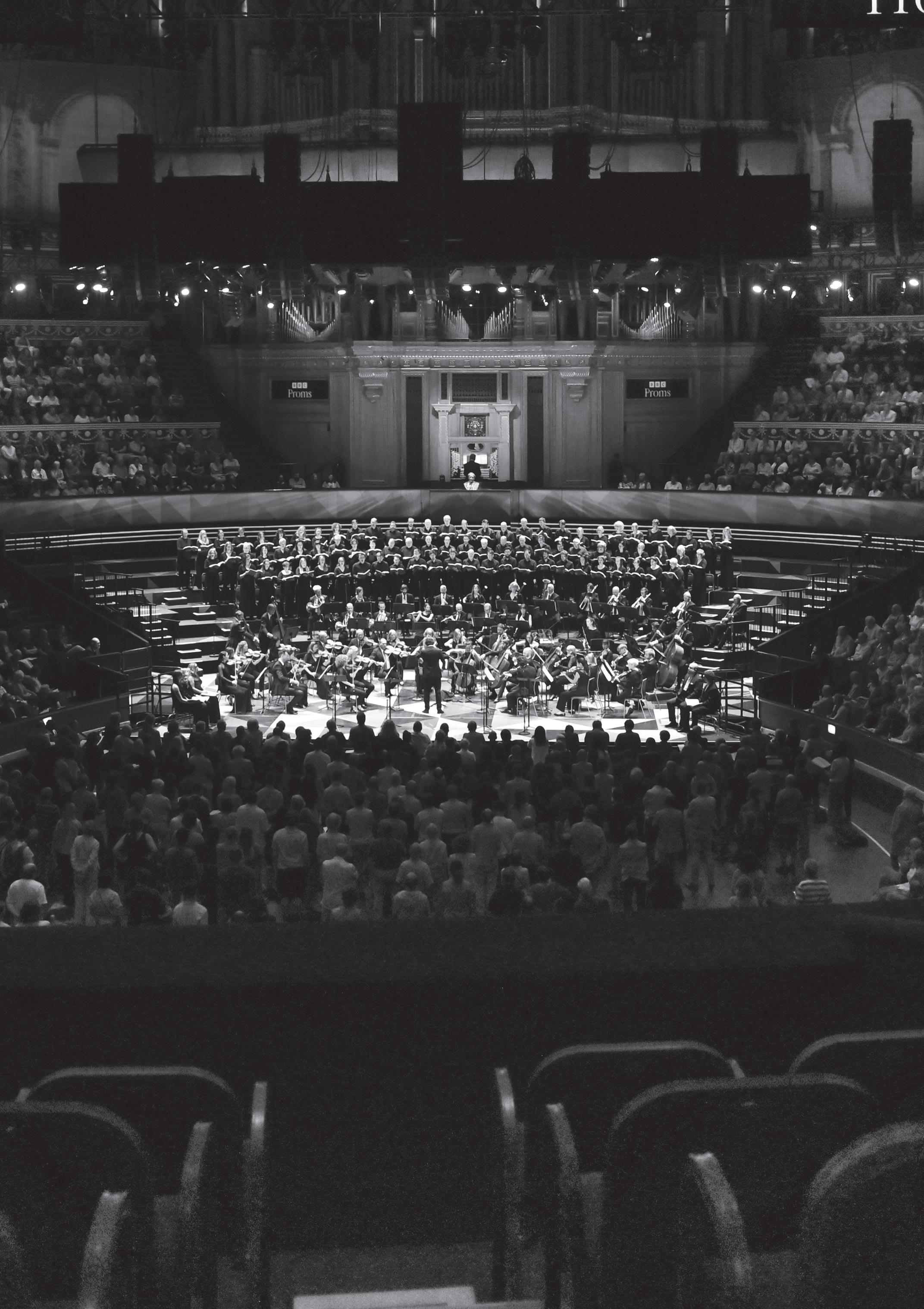

In truth, Haydn had already prepared a lot of music for his second visit while back home in Vienna. But unusually, he wrote his Symphony No.103 – the penultimate of his 12 ‘London’ symphonies, and of his entire symphonic output – in London itself, during the winter of 1794-5. It was premiered on 2 March 1795 as part of a series of socalled Opera Concerts at the King’s Theatre, now the site of Her Majesty’s Theatre in Haymarket. Unsurprisingly, it went down a treat. The Morning Chronicle wrote: ‘Another new Overture [another name for Symphony], by the fertile and enchanting Haydn, was performed; which, as usual, had continual strokes of genius, both in air and harmony. The Introduction excited deepest attention, the Allegro charmed, the Andante was encored, the Minuets, especially the trio, were playful and sweet, and the last movement was equal, if not superior to the preceding.’

There’s no doubt that Haydn was out to charm and delight his London listeners, as the review acknowledges. But he was also out to prod them gently with some surprising innovations, not least the opening, call-to-attention drumroll which gives the Symphony its nickname. It serves as an appropriately seriousminded herald for the sombre, slow introduction that follows, which seems perpetually in search of its home key (and whose first four notes can’t help but bring to mind the ‘Dies irae’ plainchant, with all its associations of divine judgement and damnation). The change of mood when the movement’s blithe, scampering faster music arrives comes as quite a shock – although Haydn reprises some of his darker, slower music just before the movement’s end.

His slow movement alternates contrasting sections in the major and minor, growing in grandeur as it progresses, and is reputed to be based on Croatian folk songs that Haydn had studied. The composer also included a substantial violin solo, destined at the Symphony’s premiere for his London orchestra’s leader, Giovanni Battisti Viotti, himself an acclaimed soloist, conductor and composer.

Haydn’s elaborate minuet and trio take us a long way away from the ballroom, in rich, complex music that quickly moves into far richer harmonic regions than its opening suggests. A gentle, rising horn figure launches the spirited finale, which derives all of its material from a single theme, first heard in the violins (and bearing a striking resemblance to the all-pervasive figure that begins Beethoven’s Fifth).

© David Kettle

The 2025/26 season sees Alina Ibragimova perform with the Budapest Festival Orchestra, Orchestre symphonique de Montréal, London Philharmonic, Wiener Symphoniker, Finnish Radio Symphony, Atlanta Symphony, Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony, Dresdner Philharmonie, Boulez Ensemble and Kammerakademie Potsdam, working with conductors Iván Fischer, Robin Ticciati, Edward Gardner, Thomas Guggeis and Krzysztof Urbański. She also play-directs the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra and Camerata Bern.

Highlights of the previous two seasons have included concerts with the Deutsches SymphonieOrchester Berlin, Netherlands Radio Philharmonic, Camerata Salzburg, Mahler Chamber Orchestra, Royal Stockholm Philharmonic, Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen, Detroit Symphony, Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin, Bamberger Symphoniker, WDR Sinfonieorchester and City of Birmingham Symphony, with conductors Vladimir Jurowski, Hannu Lintu, Ryan Bancroft, Maxim Emelyanychev and Anja Bihlmaier.

In recital, Alina regularly performs with pianist Cédric Tiberghien and together they continue their cycle of Beethoven’s sonatas for violin and piano on period instruments at Wigmore Hall. Other chamber projects this season include recitals at Berlin’s Boulez Saal and Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw and Muziekgebouw, as well as performances with the Chiaroscuro Quartet of which Alina is a founding member.

For full biography please visit sco.org.uk

The Scottish Chamber Orchestra (SCO) is one of Scotland’s five National Performing Companies and has been a galvanizing force in Scotland’s music scene since its inception in 1974. The SCO believes that access to world-class music is not a luxury but something that everyone should have the opportunity to participate in, helping individuals and communities everywhere to thrive. Funded by the Scottish Government, City of Edinburgh Council and a community of philanthropic supporters, the SCO has an international reputation for exceptional, idiomatic performances: from mainstream classical music to newly commissioned works, each year its wide-ranging programme of work is presented across the length and breadth of Scotland, overseas and increasingly online.

Equally at home on and off the concert stage, each one of the SCO’s highly talented and creative musicians and staff is passionate about transforming and enhancing lives through the power of music. The SCO’s Creative Learning programme engages people of all ages and backgrounds with a diverse range of projects, concerts, participatory workshops and resources. The SCO’s current five-year Residency in Edinburgh’s Craigmillar builds on the area’s extraordinary history of Community Arts, connecting the local community with a national cultural resource.

An exciting new chapter for the SCO began in September 2019 with the arrival of dynamic young conductor Maxim Emelyanychev as the Orchestra’s Principal Conductor. His tenure has recently been extended until 2028. The SCO and Emelyanychev released their first album together (Linn Records) in 2019 to widespread critical acclaim. Their second recording together, of Mendelssohn symphonies, was released in 2023, with Schubert Symphonies Nos 5 and 8 following in 2024.

The SCO also has long-standing associations with many eminent guest conductors and directors including Principal Guest Conductor Andrew Manze, Pekka Kuusisto, François Leleux, Nicola Benedetti, Isabelle van Keulen, Anthony Marwood, Richard Egarr, Mark Wigglesworth, Lorenza Borrani and Conductor Emeritus Joseph Swensen.

The Orchestra’s current Associate Composer is Jay Capperauld. The SCO enjoys close relationships with numerous leading composers and has commissioned around 200 new works, including pieces by Sir James MacMillan, Anna Clyne, Sally Beamish, Martin Suckling, Einojuhani Rautavaara, Karin Rehnqvist, Mark-Anthony Turnage, Nico Muhly and the late Peter Maxwell Davies.

Each year, the SCO must fundraise around £1.2 million to bring extraordinary musical performances to the stage and support groundbreaking education and community initiatives beyond it.

If you share our passion for transforming lives through the power of music and want to be part of our ongoing success, we invite you to join our community of regular donors. Your support, no matter the size, has a profound impact on our work – and as a donor, you’ll enjoy an even closer connection to the Orchestra.

To learn more and support the SCO from as little as £5 per month, please contact Hannah at hannah.wilkinson@sco.org.uk or call 0131 478 8364.

SCO is a charity registered in Scotland No SC015039.