FROM THE FOREST TO THE FORGE LACHLAN GOUDIE

The Scottish Gallery is delighted to present From the Forest to the Forge, an ambitious exhibition by Lachlan Goudie. This bold body of work reflects a fifteen-year journey across Britain’s industrial heartlands and natural landscapes.

Lachlan’s project is a remarkable act of witness. From the shipyards of the Clyde and the blast furnaces of Wales, to the dismantling of oil rigs and the laboratories of satellite technology, he has sought out the places where industry has shaped both the landscape and our national imagination. What he has created is not only an artistic record of engineering marvels and working lives, but also a deeply human chronicle of resilience, transformation, and loss.

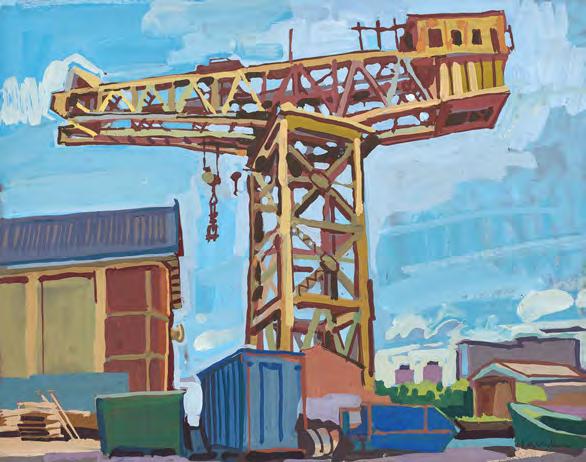

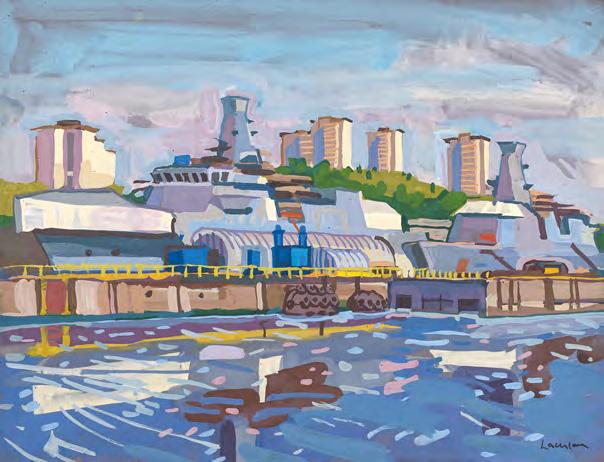

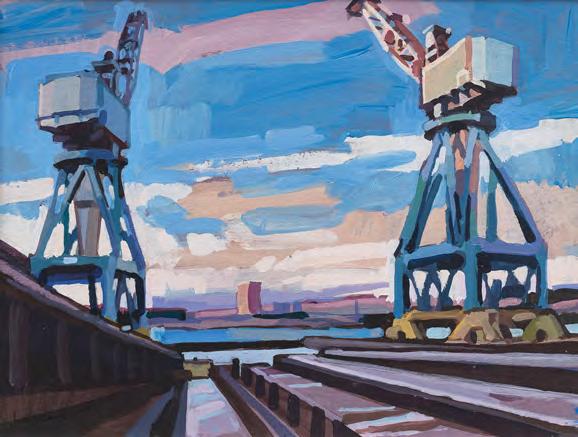

These paintings, drawings and etchings remind us of the scale and energy of traditions that have defined communities for generations: shipbuilding, steelmaking, quarrying and mining. Lachlan’s images capture both the grandeur of these industries at their height and the poignancy of their decline, while also turning our gaze towards new technologies and the workers whose skill and pride remain central to the story.

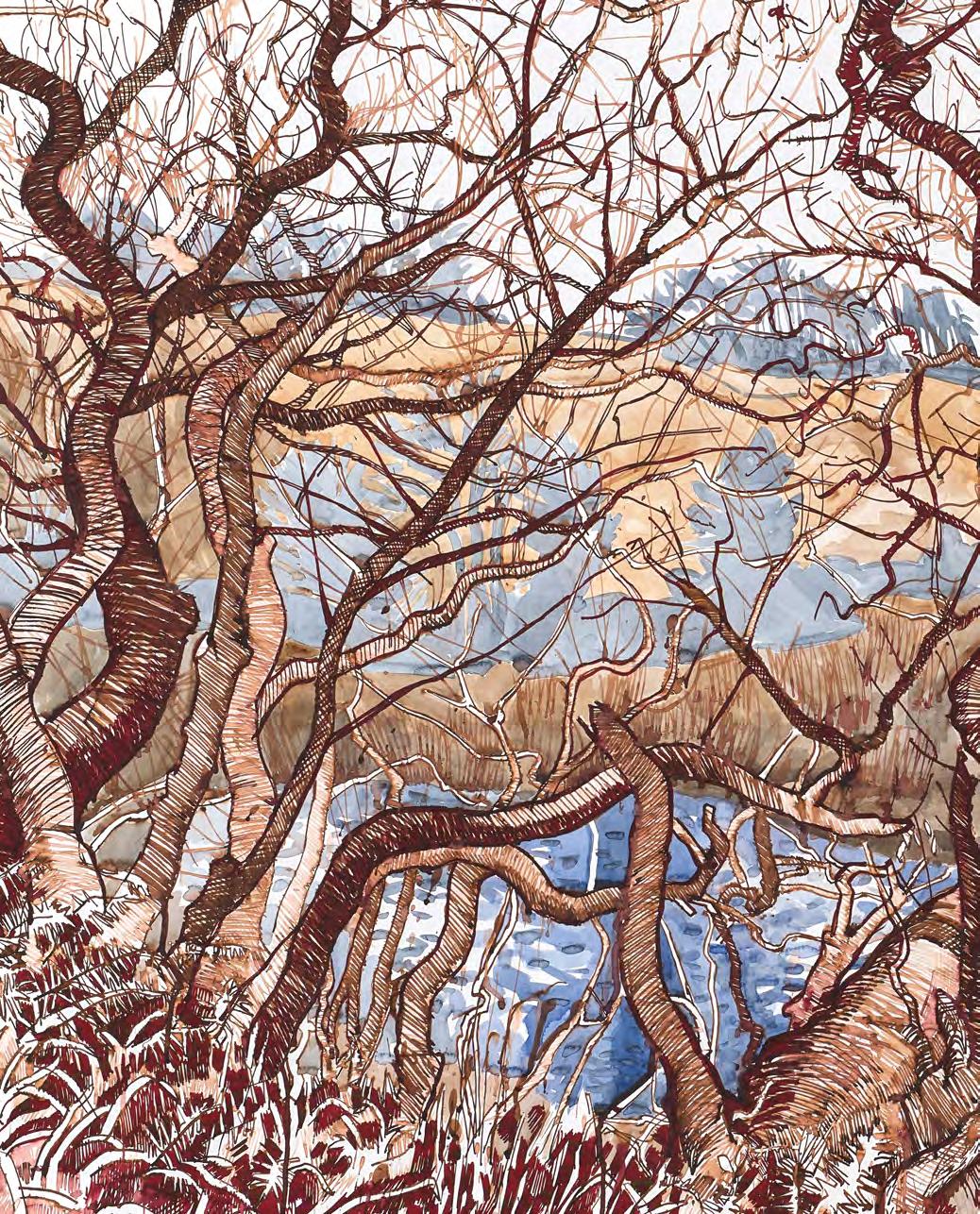

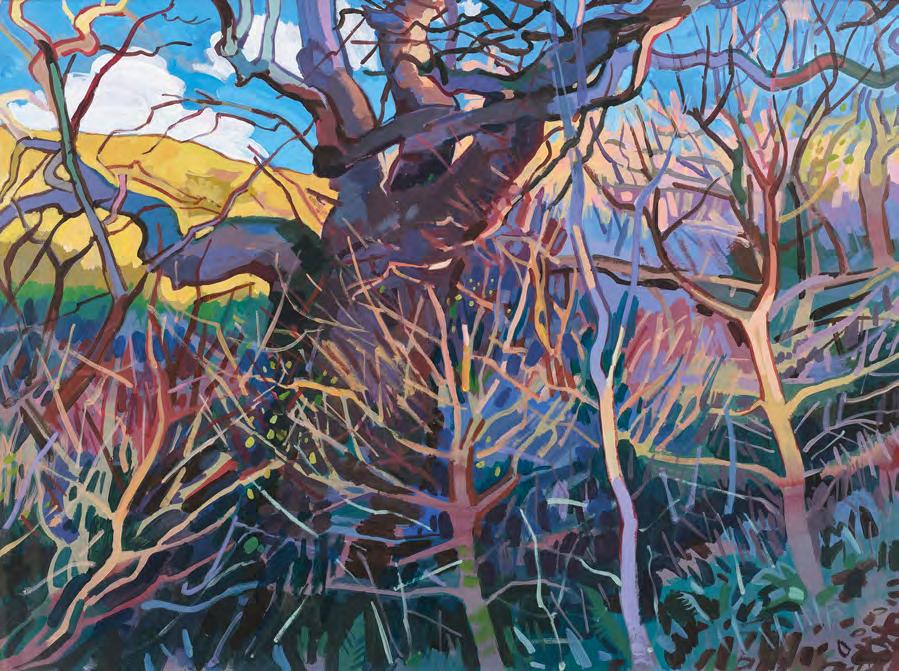

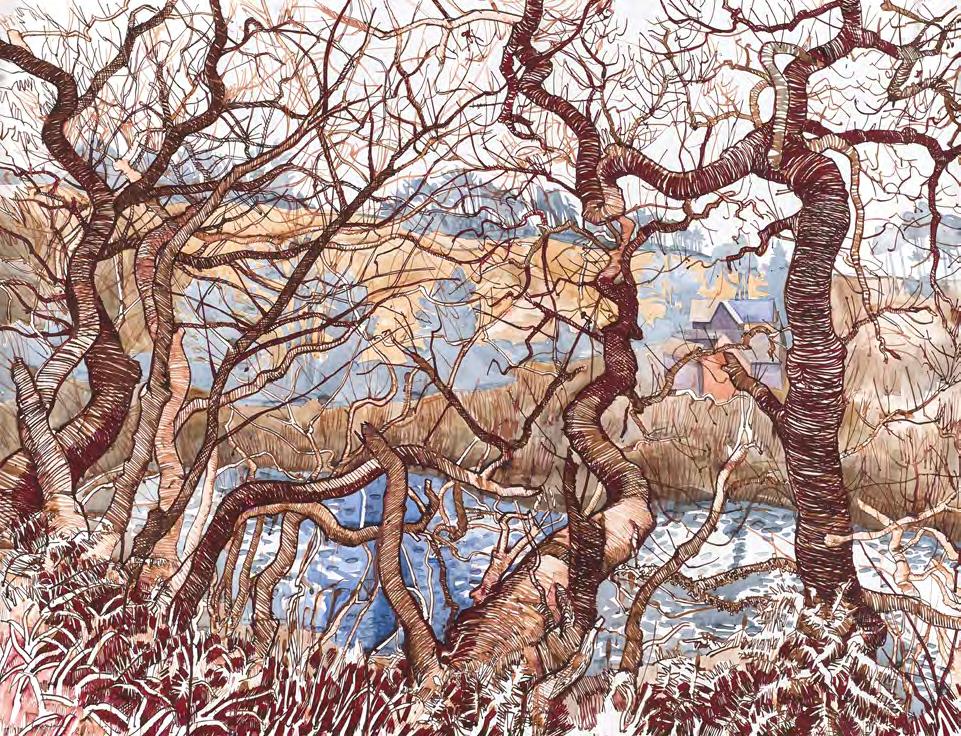

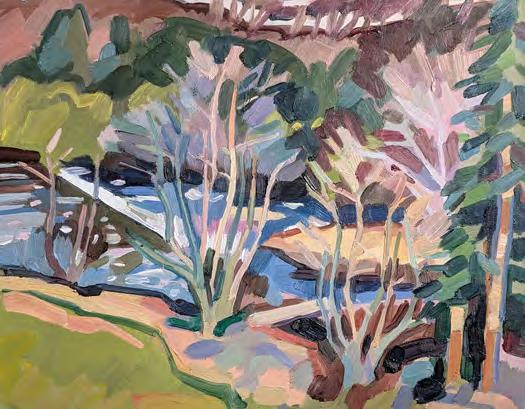

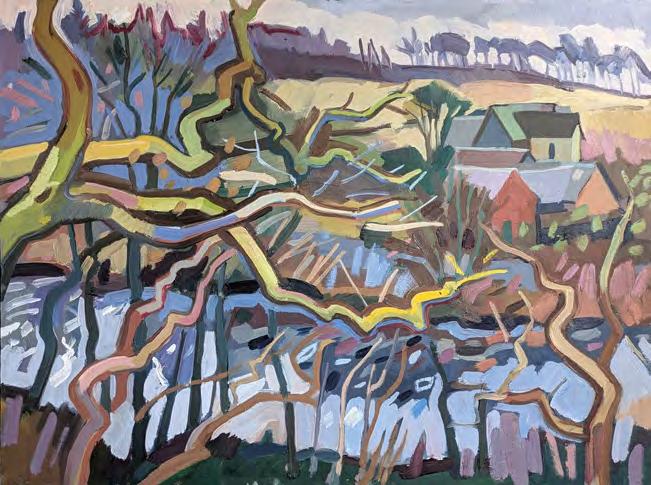

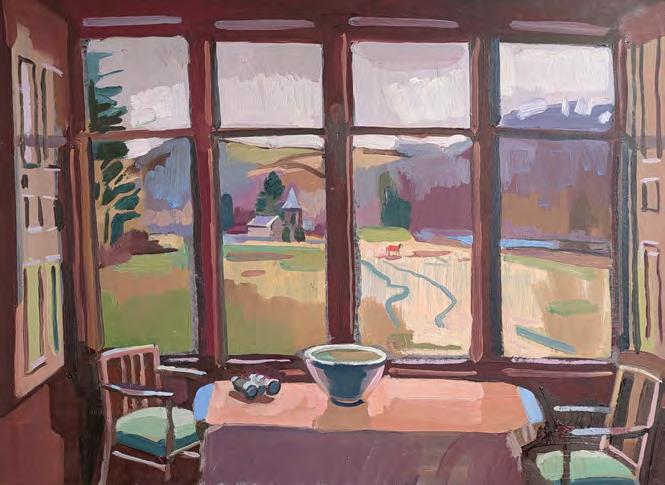

Equally compelling are works in dialogue with these industrial scenes: paintings of ancient woodlands, enduring trees and natural architecture. By placing these environments alongside one another, Lachlan reveals that industry and nature are not opposing worlds but interconnected landscapes. Each has a sublime beauty and each helps to shape our sense of who we are.

This exhibition continues a distinguished tradition in British art of drawing inspiration from both the pastoral and the industrial. Lachlan Goudie reminds us that dignity, awe and even poetry can be found in the places where human endeavour meets the natural world.

From the Forest to the Forge is more than one artist’s journey: it is a celebration of achievement, a record of change, and a reflection on the landscapes, both natural and man-made, that define us.

I have always been fascinated by industry and over the last 15 years I have spent time drawing and painting in many extraordinary industrial locations across the United Kingdom. From shipyards on the River Clyde, to blast furnaces in Wales and high-tech satellite manufacturing laboratories in Portsmouth, I have found creative inspiration in the unlikeliest of studios.

My visits to engineering sites, factories, slate quarries and mines have, over the years, enabled me to compile an unusual archive of drawings and paintings - essentially a picture history of modern British industry. It’s a story of national achievement, pride and technological innovation and for the first time, this exhibition brings together the complete range of works produced during my fifteenyear painting pilgrimage across Industrial Britain.

From the Forest to the Forge is a project which has made me consider how industry has shaped British landscape and culture. The exhibition features paintings that document the last days of steel production in Port Talbot; drawings illustrating the dismantling of immense offshore rigs, structures which once defined the North Sea Oil boom, and portraits of the workers I have encountered - people who often identify closely with the history and the economic importance of the jobs they do.

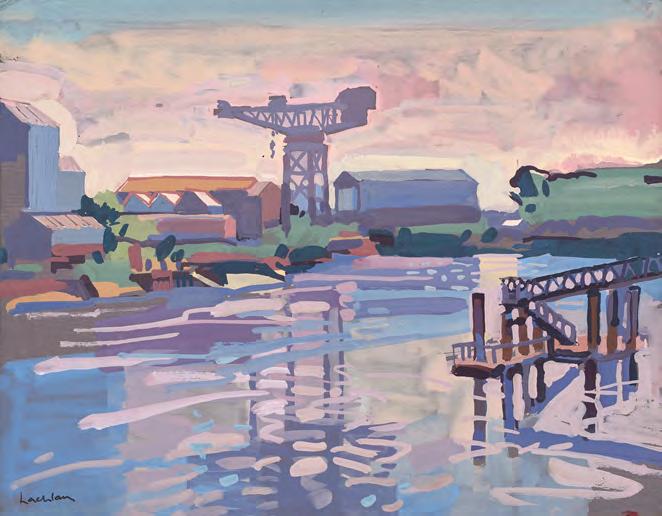

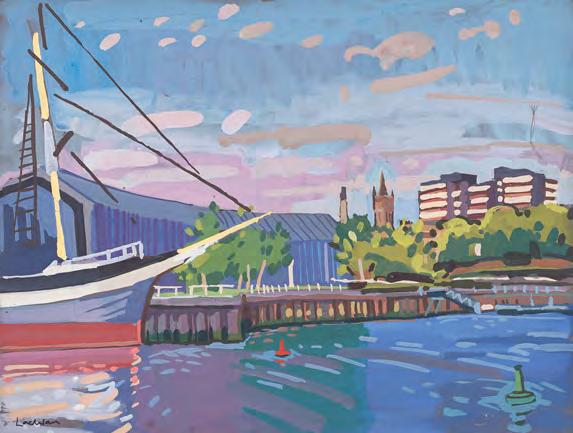

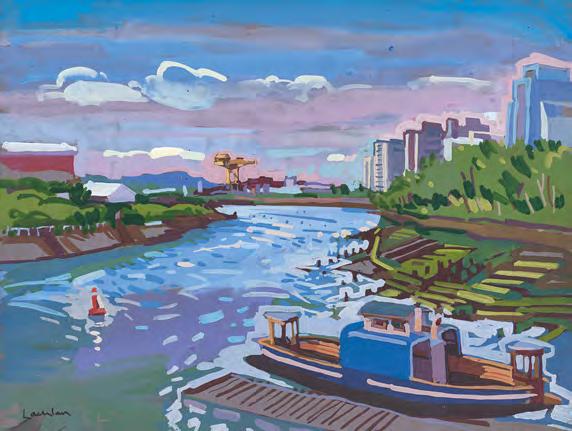

When I was growing up in Glasgow in the 1980s, my father would often describe the days when the River Clyde bustled with shipbuilding. But when I went to see for myself, the river was silent. My response was to start drawing the archaeology of a dying industrial landscape, desperate to re-kindle something of what I had missed along the Clyde.

In time, I gained access to the BAE shipyards in Govan and Scotstoun (the last two major yards surviving on the Clyde) and my first visits coincided with a resurgence of shipbuilding activity. I was the only artist permitted on site to document the construction of Britain’s vast naval flagships, the Queen Elizabeth Class aircraft carriers, and the craftsmen and women involved in that project.

My experiences on the Clyde motivated me to seek out other locations that might contribute to a portrait of working Britain. Over the course of more than a decade I have made painting trips to, amongst other places, the UK’s deepest mine in Yorkshire, one of the world’s largest slate quarries at Dinorwig in Wales, the country’s most important oil refinery and a steel furnace the size of St. Paul’s Cathedral.

In many cases, I have borne witness to the decline of an industrial tradition and observed the social and environmental impact this

represents. My paintings record the end of steel manufacturing at Redcar, the changing skyline of Glasgow as Titan cranes were demolished and replaced, and the dismantling of oil rigs in Hartlepool. On other occasions I have been able to document the resilience of steel rolling at Dalzell (adjacent to the once immense Ravenscraig steel works) as well as the advance of innovative new technologies at satellite manufacturing labs or engineering suppliers for offshore windfarms.

Many of us treasure the idea that we are a pastoral nation. Industry and nature, however, are presented as being in perennial conflict. The legacy of heavy industry and the environmental pressure this creates, has placed them at odds with one another. But as an artist I find both subjects equally compelling. Britain’s natural and industrial landscapes are interdependent; they affect and influence one another. And through the course of my work, I have discovered that they also share many characteristics; sublime scale and intricacy are elements that feature in both environments.

From the Forest to the Forge includes many works inspired by woods, trees, and the wonders of natural engineering. I have tried to place the different facets of our national landscape in dialogue with one another. To celebrate the complexity and beauty that can be found not only in nature, but in our industrial hinterlands - the sites of engineering and

scientific innovation that have contributed to making us who we are.

And I am not the first painter to find myself enthralled by both industry and the British countryside. Over the centuries there are many artists who didn’t see a contradiction in taking their inspiration from nature as well as the factories, forges and awesome engineering sites that built the modern nation. Landscape painters like J.M.W. Turner, Stanley Spencer, Graham Sutherland and Laura Knight also produced a range of responses to the story of British industry, from social critique to celebrations of the industrial sublime. For these artists the landscape of industry must have appeared new and strange, but they brought many of the values of great landscape painting to their task. They chose to find beauty where others saw only industrial ugliness.

From the 18th century onwards, this principle has not only motivated painters but writers, filmmakers and musicians across Britain. From L.S. Lowry to J.B. Priestly and Ridley Scott, artists of all kinds have been inspired by the stories of labour and the imagination, of work and common endeavour that lie embedded in our national family tree. I hope that the drawings, paintings and prints exhibited in From the Forest to the Forge will add, in some small way, to that tradition.

FROM THE FOREST TO THE FORGE

OIL RIG, STEELWORKS & SPACE LAB LANDSCAPE

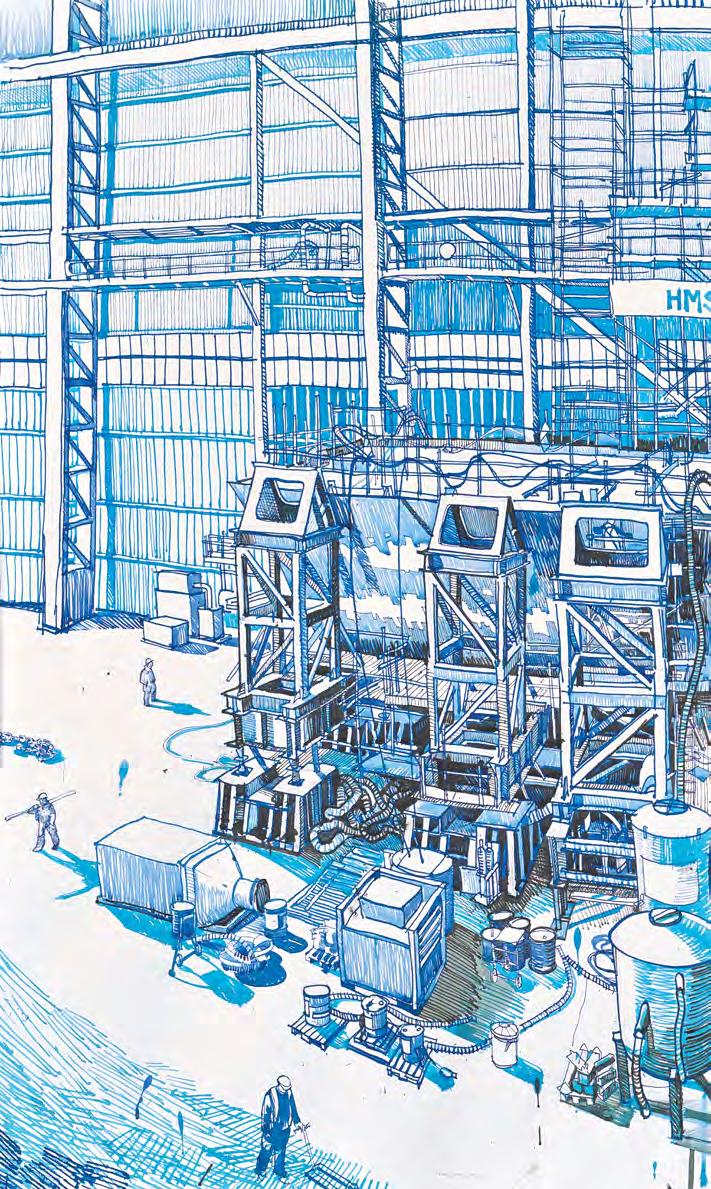

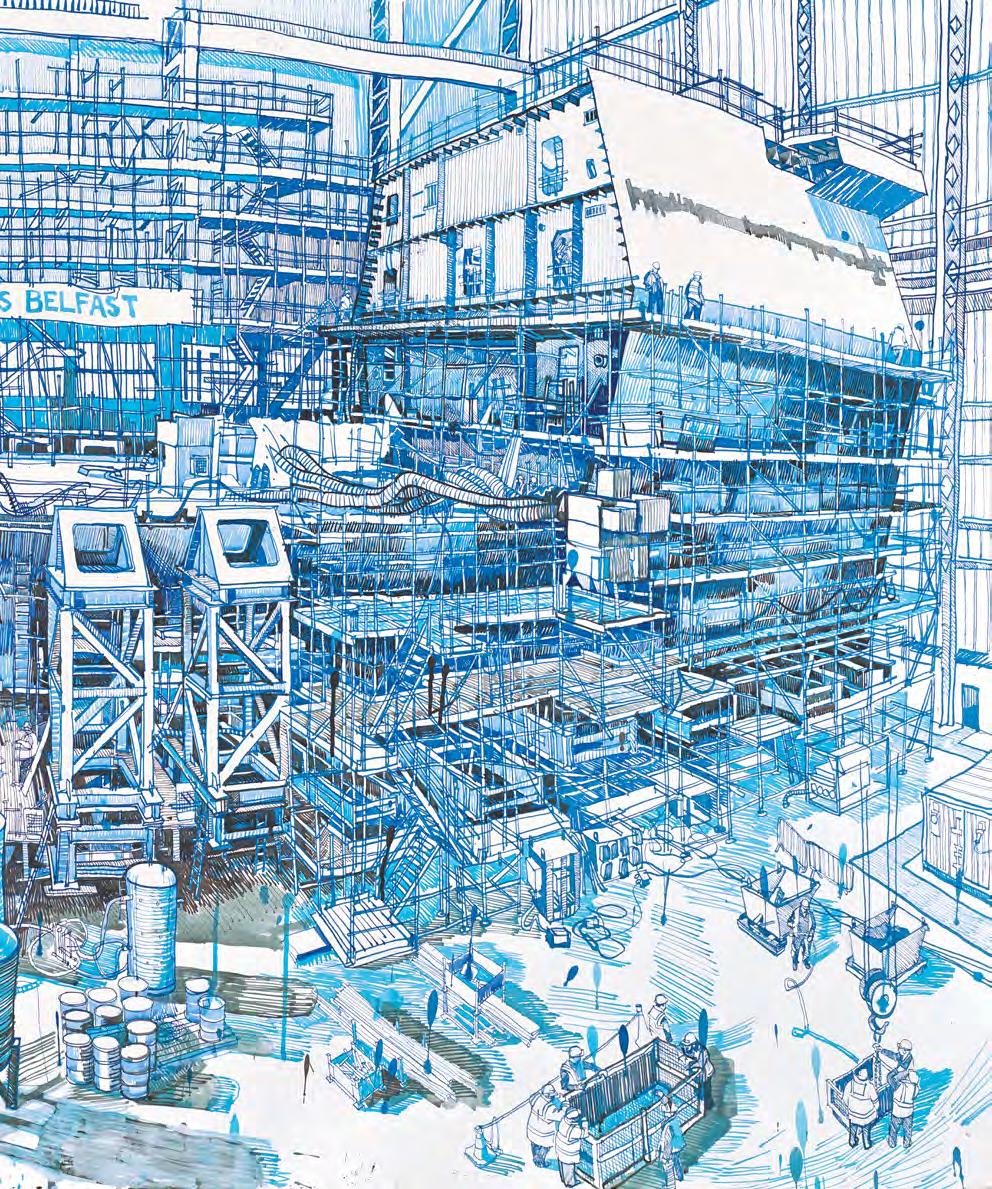

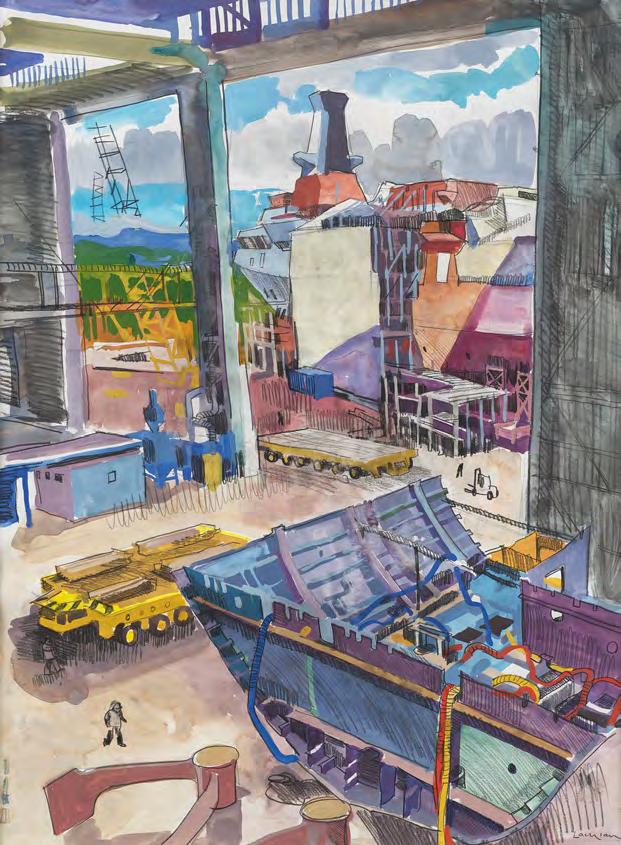

My experience of drawing and painting in the shipyards of Scotland began in 2010. Since then I have worked at sites in Govan and Scotstoun on the Clyde and at Rosyth on the Firth of Forth. I was provided with access through the generosity of the engineering companies BAE and Babcock, to whom I am extremely grateful.

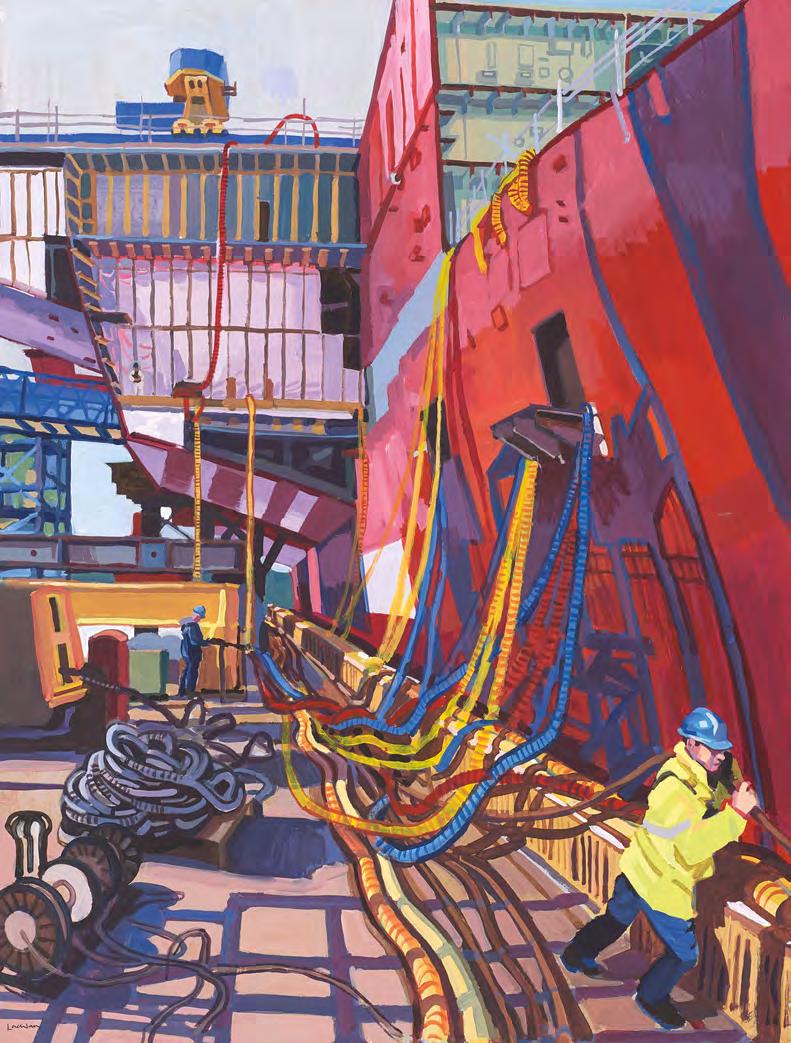

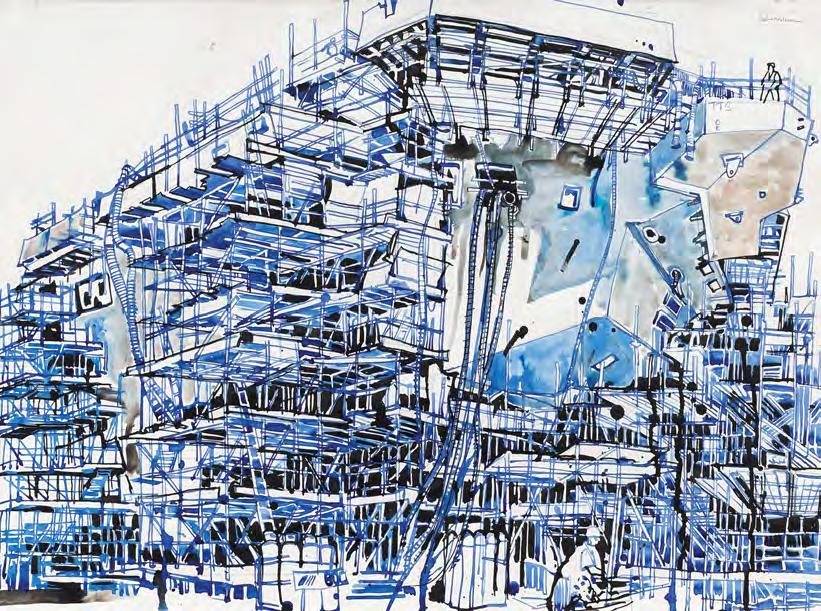

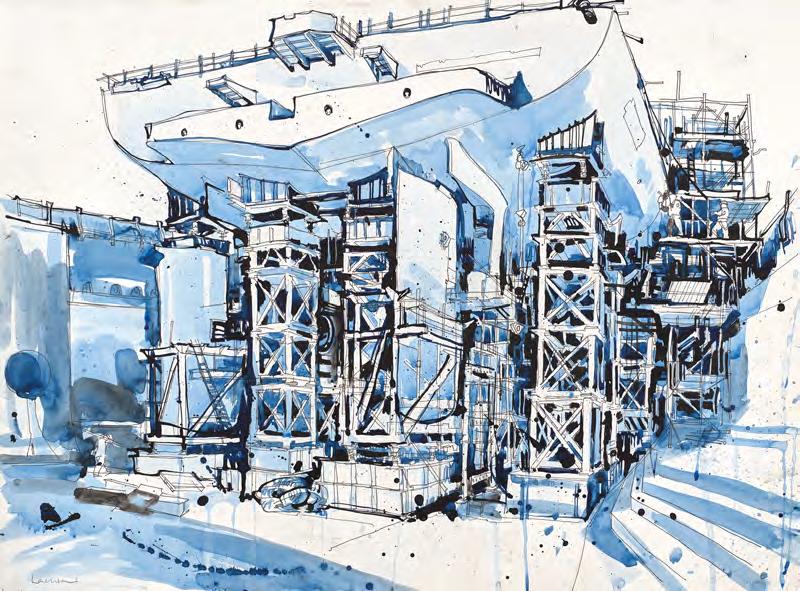

Shipyards are extraordinary places. The sublime sense of scale and energy, the furious and relentless pace of component panels being assembled into towering monuments of steel. There is noise, there is chaos and fire, there’s a visceral sense that you’re part of a vast, industrial organism that will spit you out, unless you watch your step.

I have been particularly influenced by two artists who experienced this thrill before me; Muirhead Bone and Stanley Spencer. During WWI and WWII these artists captured the frenzy of naval construction on the Clyde in their sketchbooks. Such was the pace of Muirhead Bone’s industriousness (working at the same Fairfield yard where I have spent so much time) he would strap the notebooks to his hand. That way he could move speedily from one scene to the next, constantly scribbling the activity that unfolded before him. Spencer would draw on long rolls of toilet paper to maintain his creative momentum.

My fascination with shipbuilding as a subject was inspired by the work of these artists but

also by a childhood encounter with the late Jimmy Reid, the celebrated Scottish Trades Union leader. When I was boy I interviewed him for a school project and during a conversation conducted in the sitting room of his flat in Glasgow, he asserted We don’t just build ships on the Clyde, we build men. The experience made a great impact on me.

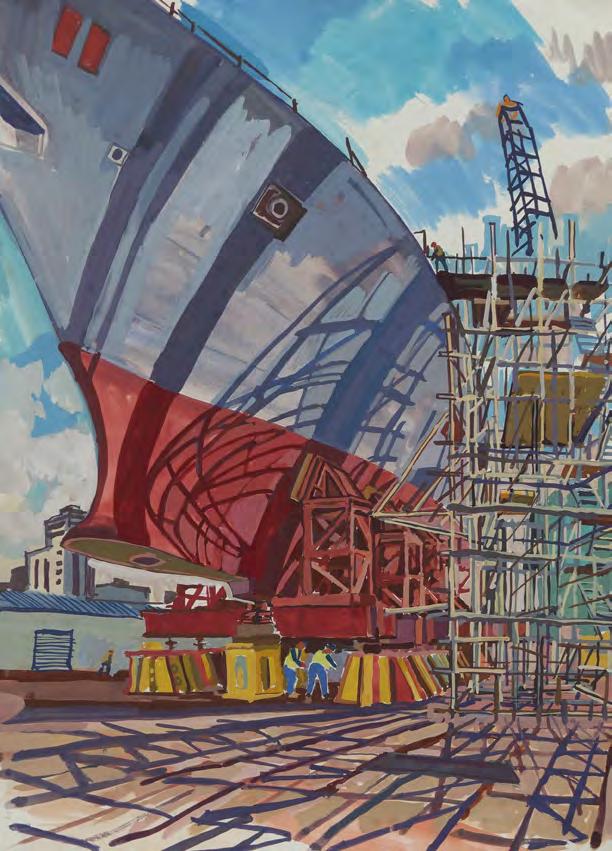

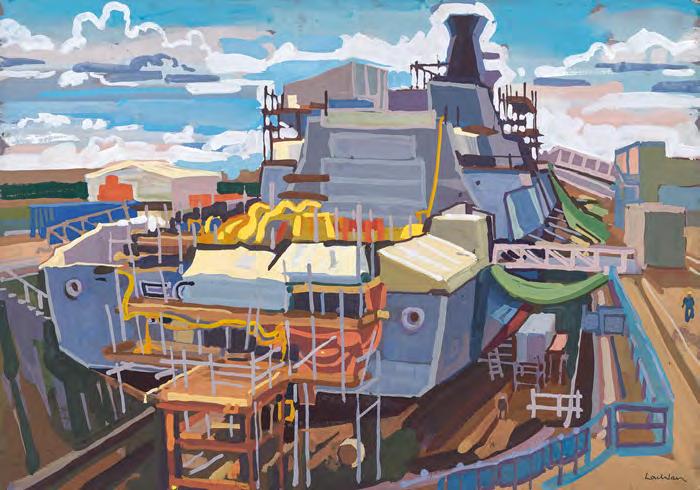

When I began visiting the old Fairfield yard in Govan in 2010, they were engaged in a series of new projects constructing vessels for the Royal Navy. Initially I documented the assembly of a series of Type 45 Destroyers between 2010 and 2013.

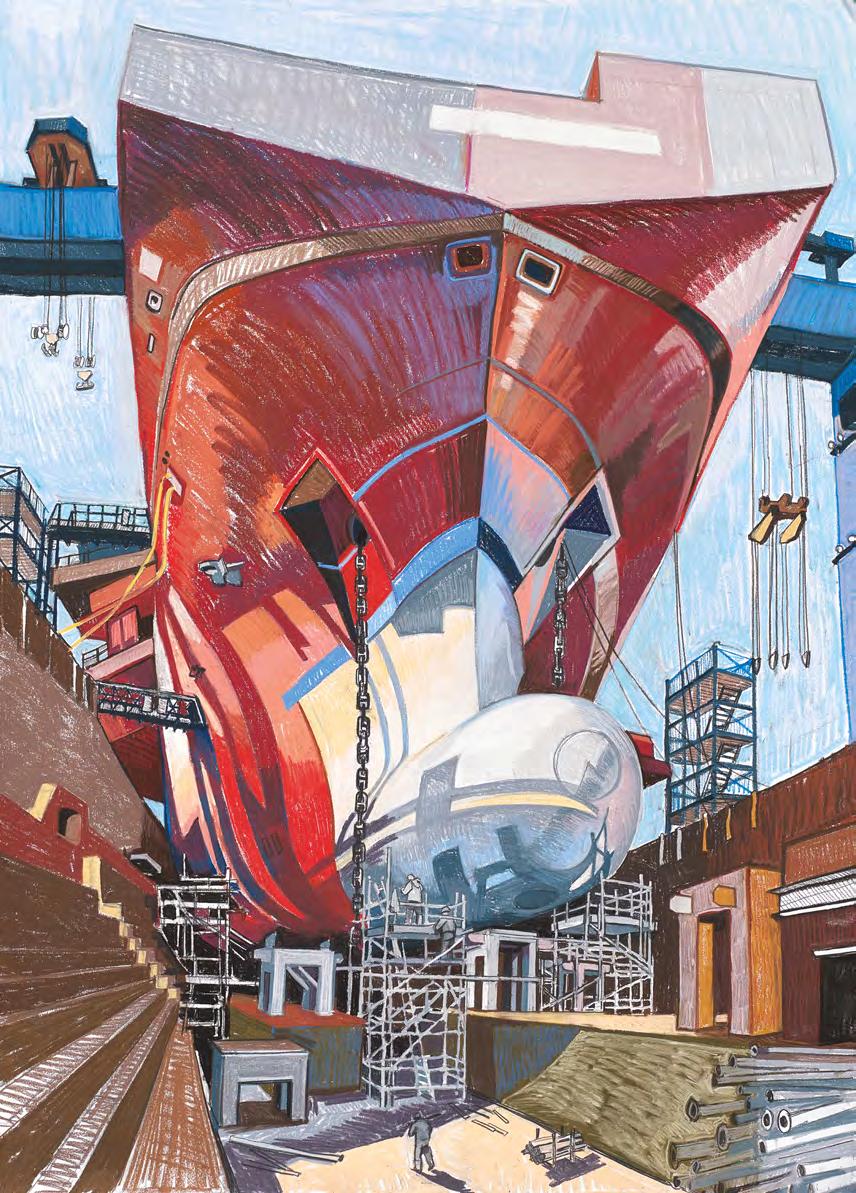

On my first painting day at Govan the Type 45 destroyer HMS Duncan was nearing completion on the slipway. She was the final vessel to be launched into the Clyde using the traditional ‘dynamic’ launch process. This technique, where a vessel is entirely built on the stocks and dramatically released into the river, has been replaced by modern methods of construction.

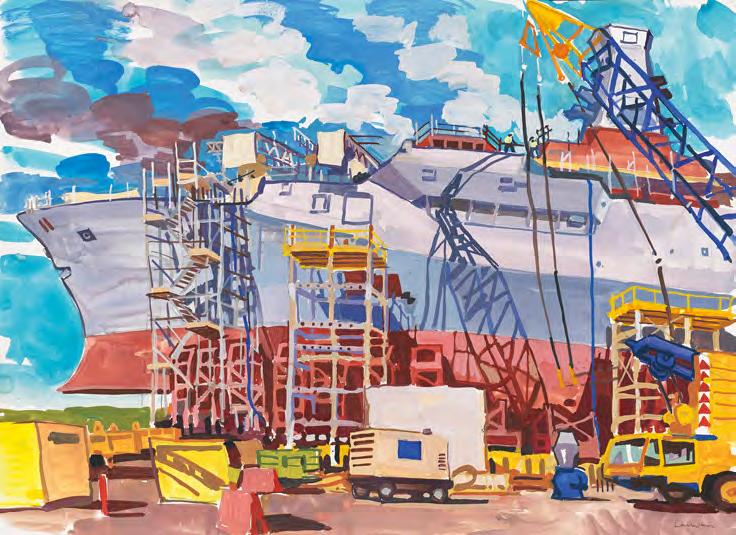

Between 2010 and 2017 I was able to document the building of Britain’s two aircraft carriers, the Queen Elizabeth and Prince of Wales. This endeavour, the largest shipbuilding project ever undertaken for the Royal Navy, involved yards across the United Kingdom. On completion the carriers would ultimately weigh 65,000 tonnes and across the country over 10,000 workers were involved in the project.

It was a demonstration of human ambition, discipline, imagination and creativity that I found immensely humbling.

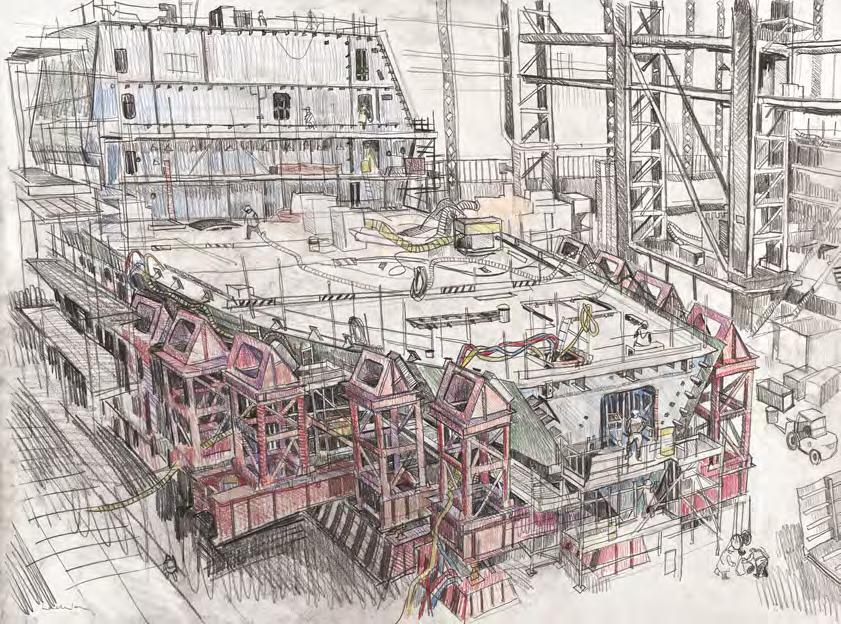

At Govan, hundreds of individual steel units were welded together and built up into vast blocks, measuring 7 decks in height. These segments were then shipped from the Clyde to the Firth of Forth where the two carriers were eventually assembled in a huge dry dock at Rosyth Dockyard. I was able to record every stage in this process of construction.

Since 2017 a contract for a series of Type 26 Frigates at the Govan yard, has kept thousands of workers busy. I have been on site regularly and in my drawings have been able to capture an incredible change in the approach to Clydebuilt shipbuilding; a shift from assembling vessels on slipways to working in vast covered halls.

Whilst sometimes a sense of nostalgia and romanticism attaches itself to the industry of shipbuilding, on the ground the process is ferociously unsentimental. Iconic cranes are knocked down, the environment is regularly transformed, building methods evolve and change. It was my ambition to capture the scale and frenetic energy of the modern yard, as well as chronicling the human experience of such a rapidly changing working environment.

1 Shipbuilding ink and wash on paper

When I first arrived at Govan the Type 45 destroyer HMS Duncan was nearing completion on the slipway. She was the final vessel to be launched into the Clyde using the traditional ‘dynamic’ launch process. This technique, where a vessel is entirely built on the stocks and dramatically released into the river, has been replaced by modern methods of construction.

2 Govan Slipway No 1 charcoal, chalk and watercolour on paper, 51 x 68 cm

3 Dockside Morning

4 A New Start

At Govan, hundreds of individual steel units were welded together and built up into vast blocks, measuring 7 decks in height. These segments were then shipped from the Clyde to the Firth of Forth where the two carriers were eventually assembled in a huge dry dock at Rosyth Dockyard.

11 Forward Block carbon and pencil on paper, 51 x 68 cm

10,000 workers were involved in constructing the Queen Elizabeth Class Carriers. At Govan they laboured through the night in order to assemble each of the vast hull segments. It was a demonstration of human ambition, discipline, imagination and creativity that I found immensely humbling.

Govan by Night pastel on paper, 100 x 150 cm

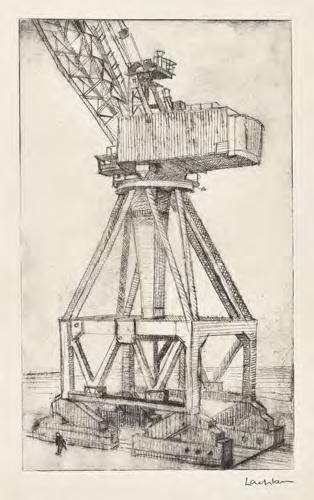

This image is the first major work to be inspired by my encounter with shipbuilding. During the fifteen years I have spent sketching by the Clyde, the geography of the Govan yard and the methods of naval construction undertaken there, have changed completely. I witnessed the many cranes that dominated Fairfield’s being dismantled and unwittingly captured the last days of a series of monuments that had defined Glasgow’s skyline for decades.

23

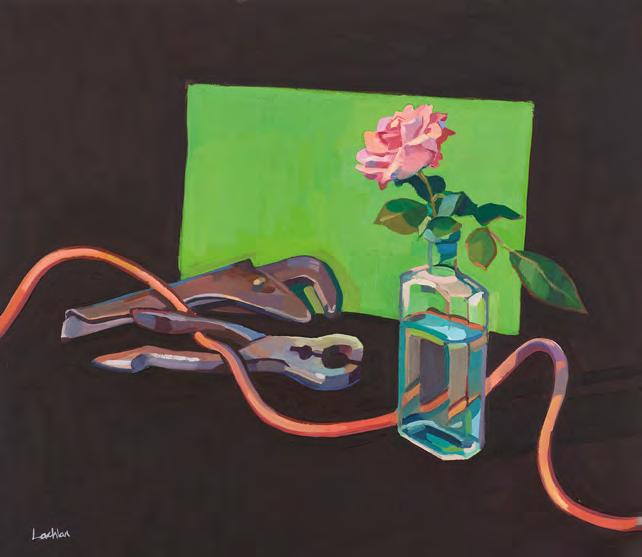

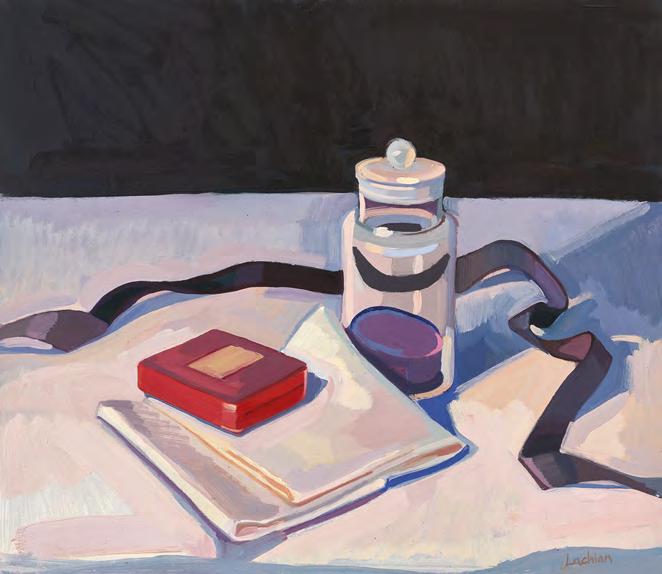

One of my painting heroes J.D. Fergusson, created a series of images in Portsmouth dockyards during WWI. The graphic dynamism of Fergusson’s compositions, in which he simplified bulky industrial forms and deployed a striking colour palette of rusty reds and cobalt blues, transformed a mundane dockyard subject into something almost abstract and thrilling. I have gleaned many lessons from these paintings and applied them, perhaps surprisingly, to a series of industrial still lives.

I think the tools of industry have a particular beauty. In these still lives I have tried to curate arrangements that feature the sorts of implements I use every day in my painting studio, alongside the vices, spanners and drills I often come across in the yards. The compositions are painted in a garish range of bright yellows, limes, oranges and electric blues. These are the colours of Health and Safety and Personal Protective Equipment, a colour palette which is omnipresent at every engineering location. My hope was to create a sort of industrial elegance from the most unlikely combination of elements.

32 A Pause from Labour oil on board, 48 x 56 cm

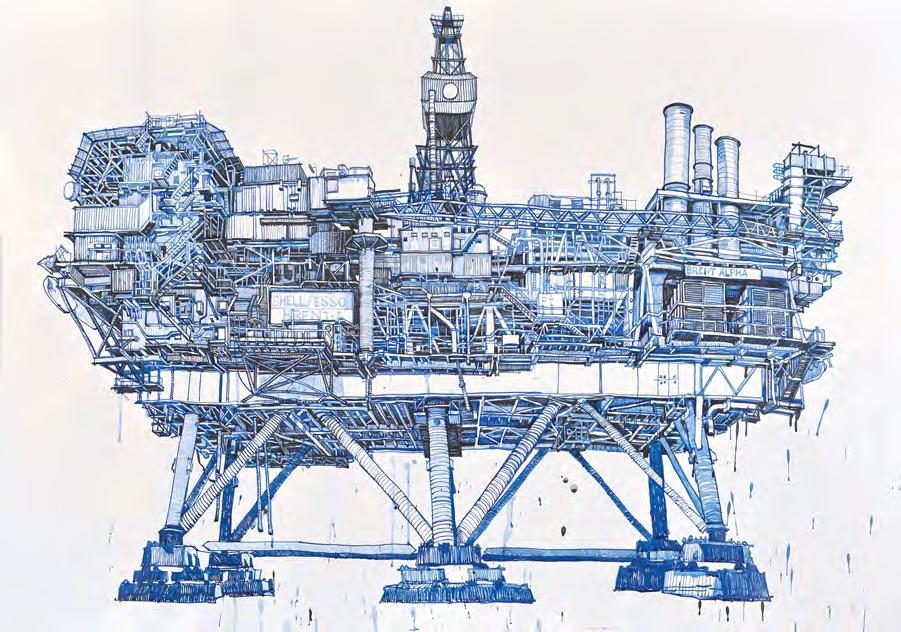

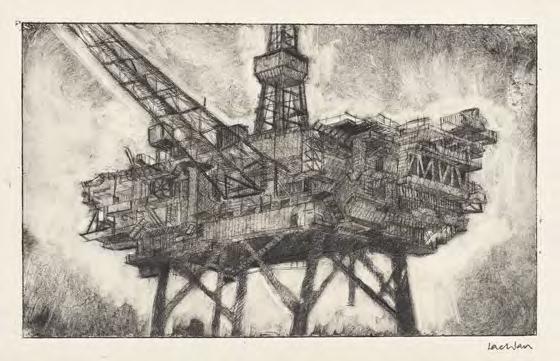

In 2020 I was granted access to the Able marine decommissioning site at Seaton Port. My visit was made possible with the permission of Shell UK. At the time they had just started decommissioning the 31,500 tonne North Sea Oil platform, Brent Alpha. This oil rig was assembled in Scotland in 1976, the year of my birth, but after 44 years exposed to wild weather of the North Sea it now found itself beached on Teeside. The colossal, steel megastructure dominated the landscape for miles around. As I drew, it towered over me, looking as alien as a rusting space station which had somehow had landed on the outskirts of Hartlepool.

The dismantling of this oil rig was not a subject that I felt was suited to careful and precise documentation. Instead I worked with speed, trying to convey the sense of constant activity that bustled around me. I used pen and ink to splatter sketches on large sheets of paper, studying the great steel supports, pipes and tubes that poured from the structure like intestines.

A few years earlier, I had experienced another site of heavy industry, one that felt equally monumental in its own way: the blast furnaces of Port Talbot. My visit to Port Talbot in 2017 was an awe-inspiring experience. Clothed in layers of protective equipment, I watched as giant ladles were manoeuvred into position then tipped over, pouring molten steel into the furnaces. The noise, heat and explosive energy I encountered was incredibly intimidating, but it was also exciting; the essence of the industrial sublime.

Port Talbot remained the centre of British traditional steelmaking until 2024, when it was announced that the country’s largest steel

works would be restructured as an electric furnace.

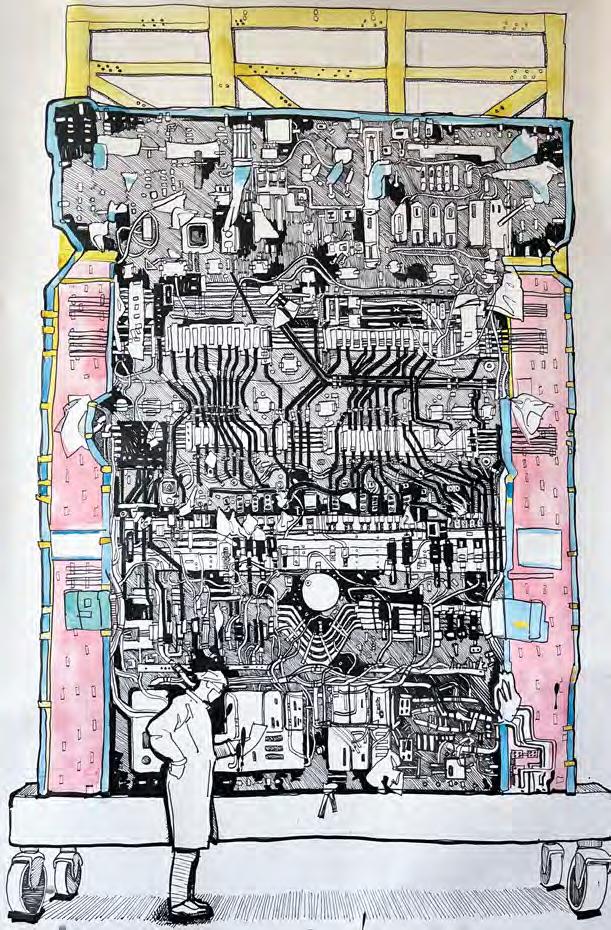

If forging steel presents a picture of Britain’s industrial past, then the Airbus laboratories in Stevenage and Portsmouth (which I visited in 2017 and 2020) offer a very different vision of the future.

The Airbus site at Stevenage dates back to 1950. It was here that the Blue Streak rocket, the first stage of the original European satellite launch vehicle, was developed by de Havilland. The mid 20th Century marked the high point of British confidence in large-scale technology. This spirit of was optimism was embodied by the 1951 Festival of Britain (which the organisers hoped would provide ‘A Tonic to the Nation’) and a famous speech by Harold Wilson in 1963 in which he predicted that the ‘white heat of technology’ would create a prosperous new future for Britain.

Today we are more sceptical about the impact of science and technology on our lives. However, at the Airbus space and satellite manufacturing labs it’s still possible to feel a thrill of excitement at the potential of modern engineering.

During my drawing trips I witnessed the construction of state of the art satellites which will one day orbit the earth, providing seamless global telecommunication networks. The environment I encountered was laboratory clean and the predominant smell was of powerful resins and adhesives. Workers busied themselves with a quiet intensity, studying intricate circuit boards and sometimes tenderly rearranging wiring across the gold foil of these cosmic structures. They carried out their tasks in an almost monastic silence.

44 End of Days carbon and watercolour on paper, 51 x 68 cm

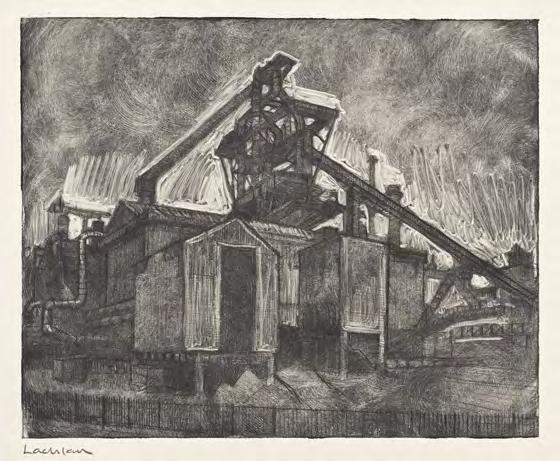

Prime Minister Gladstone once named the area of Teeside around Redcar, the ‘Infant Hercules’. At that time steel manufacture employed 40,000 people locally, helping power the Industrial Revolution. My own visits to Redcar between 2012-2017 coincided with the demise of this industrial powerhouse. In 2012 the blast furnace still hissed and steamed with a ferocious energy but after steelmaking was terminated in 2015, the structure fell silent. Although it continued to be revered as a monument by many in the community, who remain intensely proud of their industrial heritage, the blast furnace was finally demolished in 2022. This image bears witness to the final years of steel manufacture on Teeside.

46 Northern Powerhouse acrylic on board, 87 x 97 cm

49 Welder drypoint etching, 25 x 15 cm

50 Clydeside drypoint etching, 25 x 15 cm

51 Redcar drypoint etching, 19 x 25 cm

52 Shipyard drypoint etching, 19 x 25 cm

53 Deep Sea Rig drypoint etching, 15 x 25 cm

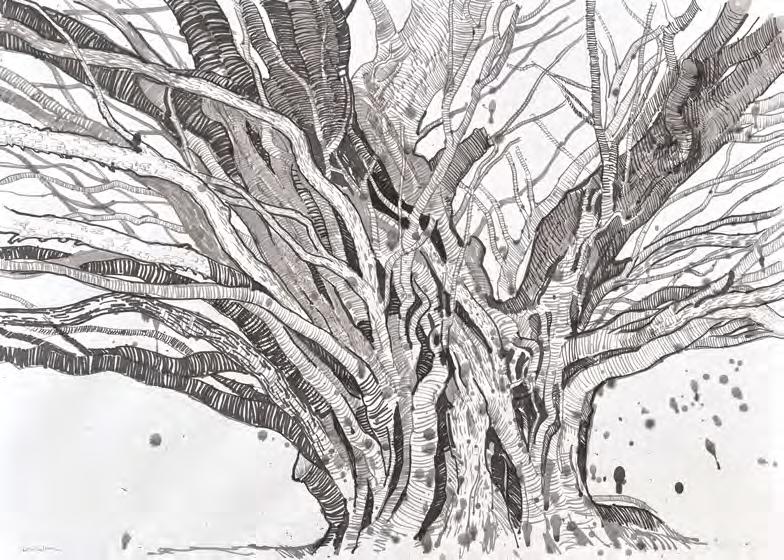

As an artist, untangling any visual logic from intricate engineering structures is a magnificent, mathematical challenge. But an even greater dilemma for me is to reconcile the promise of technology, with industry’s power to impact disastrously on the environment. In parallel with my project to document industrial sites across Britain I have spent time drawing and painting in the woods of the Scottish Borders and in Dorset.

Deep in these ancient landscapes it’s possible to find the same intricate layering, complexity and sublime scale that has fascinated me in shipyards and oil rigs. The Eggardon Yew tree featured in this exhibition is over 2,000 years old. It’s an astonishing piece of natural architecture that extends across space but also deep through time. Many of the lessons learned whilst drawing industrial structures, equipped me to tackle this epic subject.

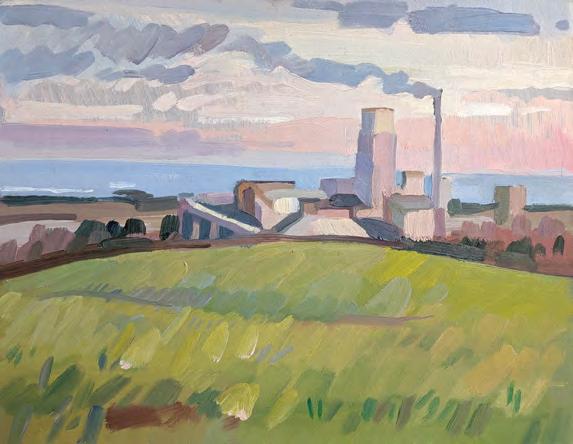

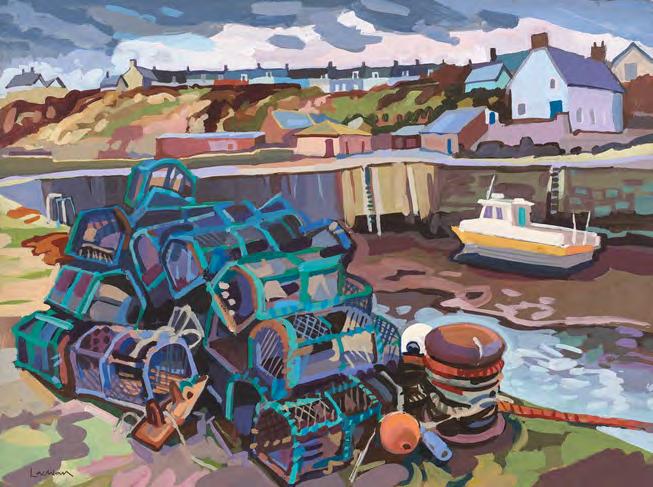

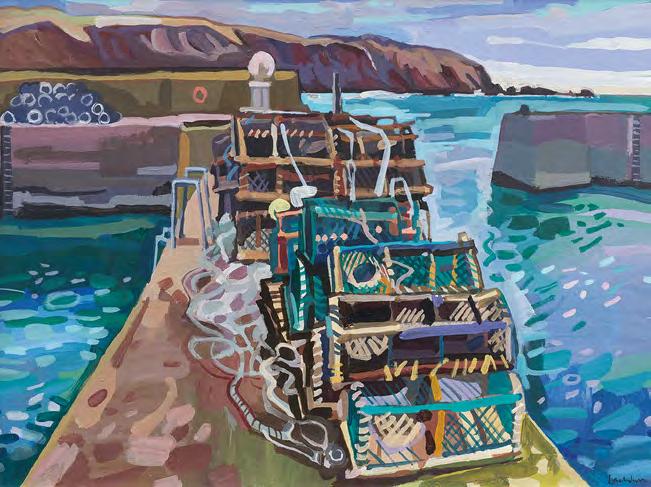

Industry is woven into our geography in many subtle ways. From the man-made hedgerows and furrows that characterise the landscape of agriculture, to the smoke rising from distant chimneys or the mountains of lobster pots that line our harbour-sides. But Britain’s natural and industrial landscapes are interdependent; they affect and influence one another. Only by engineering a respectful equilibrium between these two environments, can our journey from the Forest to the Forge remain an experience of awesome beauty.

The forests of Abbey Saint Bathans are a wild and ancient place. Walking through these woods you feel enmeshed by time, caught in a deep layering of nature and human history that stretches back millennia. We have long tended these landscapes; planting and labouring, cutting back, and pruning, sowing and reaping. Small harvests of flowers are a modest but life affirming reward for all this effort and industry.

62 The Forests of Abbey Saint Bathans ink and watercolour, 99 x 134 cm

This Dorset Oak tree was centuries old when it was felled by a storm in 2024. It grew in a forest, entangled within the branches of numerous neighbouring trees. One summer it became a gathering place for thousands of butterflies that swarmed around it. The name has endured.

67

Lachlan Goudie is an artist who exhibits regularly in London and New York. The scope of Lachlan’s work is broad, incorporating portraiture, still life and landscape painting. His canvasses have won numerous awards and in 2013 he was elected a member of the Royal Institute of Oil Painters, in London. In addition to painting, Lachlan is also a writer and Arts broadcaster. In 2015 he wrote and presented the landmark series The Story of Scottish Art for the BBC. The four episodes were critically acclaimed and Lachlan was nominated by the Royal Television Society Scotland for the ‘Onscreen personality of the year’ award.

Lachlan has written and presented several other documentaries for BBC television – The Art of Witchcraft (2013), Stanley Spencer: The Colours of the Clyde (2014), Awesome Beauty: The Art of Industrial Britain (2017) and Mackintosh: Glasgow’s Neglected Genius (2018). Lachlan’s most recent film Inside Museums: Glasgow’s Treasure Palace was broadcast on BBC4 in 2022. Lachlan has been a judge across three series of BBC1’s Big Painting Challenge and reprised this role on BBC1’s Celebrity Big Painting Challenge, 2018. He is also an expert presenter of BBC4’s Life Drawing Live! (2020 and 2021). Lachlan regularly contributes to the BBC World Service radio programme, From Our Own Correspondent and has presented several concerts on BBC Radio 3.

Lachlan’s first book, The Story of Scottish Art, was published by Thames & Hudson in September 2020 and his second book, The Secrets of Painting, will be released in spring 2026. Lachlan’s writing is informed by his experience of working as an artist. He is a keen proselytiser for the value of technique and craft in contemporary art and was schooled in painting by his father, the artist Alexander Goudie. The wonder of art: its power to colour and change people’s lives fascinates Lachlan.

It lies at the heart of his work as a painter, writer and broadcaster. Lachlan was born and grew up in Glasgow, Scotland, before studying English at Christ’s College, Cambridge and Fine Art at Camberwell College of Art in London.

2025 From The Forest to the Forge, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh

2022 Painting Paradise, The Scottish Galler y, Edinburgh

2020 Once Upon a Time, The Scottish Galler y, Edinburgh

2019 Shipyard, The Glasgow Art Club, Glasgow

2018 A Year at the Easel, The Scottish Galler y, Edinburgh Shipyard, National Museum of the Royal Navy, Portsmouth

2017 Shipyard, The Scottish Maritime Museum, Irvine

2015 New Paintings, Lachlan Goudie and Tim Benson, Mall Galleries, London

A Place in the Sun, The Roger Billcliffe Galler y, Glasgow

2014 These Precious Things, The Elizabeth Harris Gallery, New York

2012 St ill Life and the Opera, Glyndebourne, L ewes

Lands of Streams and Timber, The Roger Billcliffe Gallery, Glasgow

2011 A True Wilderness Heart, The Elizabeth Harris Gallery, New York

Sketch drawing prize 2011, The Rabley Drawing Centre, Marlborough

2010 The River Runs Through It, Kelvingrove Museum and Art Galler y, Glasgow

Of the Moment, Roger Billcliffe Galler y, Glasgow

2009 Dreaming Places, The Elizabeth Harris Gallery, New York

Published by The Scottish Gallery to coincide with the exhibition:

Lachlan Goudie

From the Forest to the Forge 30 October - 22 November

Exhibition can be viewed online at: scottish-gallery.co.uk/lachlangoudie

ISBN: 978-1-917803-10-6

Designed and Produced by The Scottish Gallery Printed by Pure Print

Front cover: A Mighty Endeavour, acrylic on board, 102 x 76 cm (cat. 9)

All rights reserved. No part of this catalogue may be reproduced in any form by print, photocopy or by any other means, without the permission of the copyright holders.

16 Dundas Street | Edinburgh | EH3 6HZ | 0131 558 1200 | scottish-gallery.co.uk