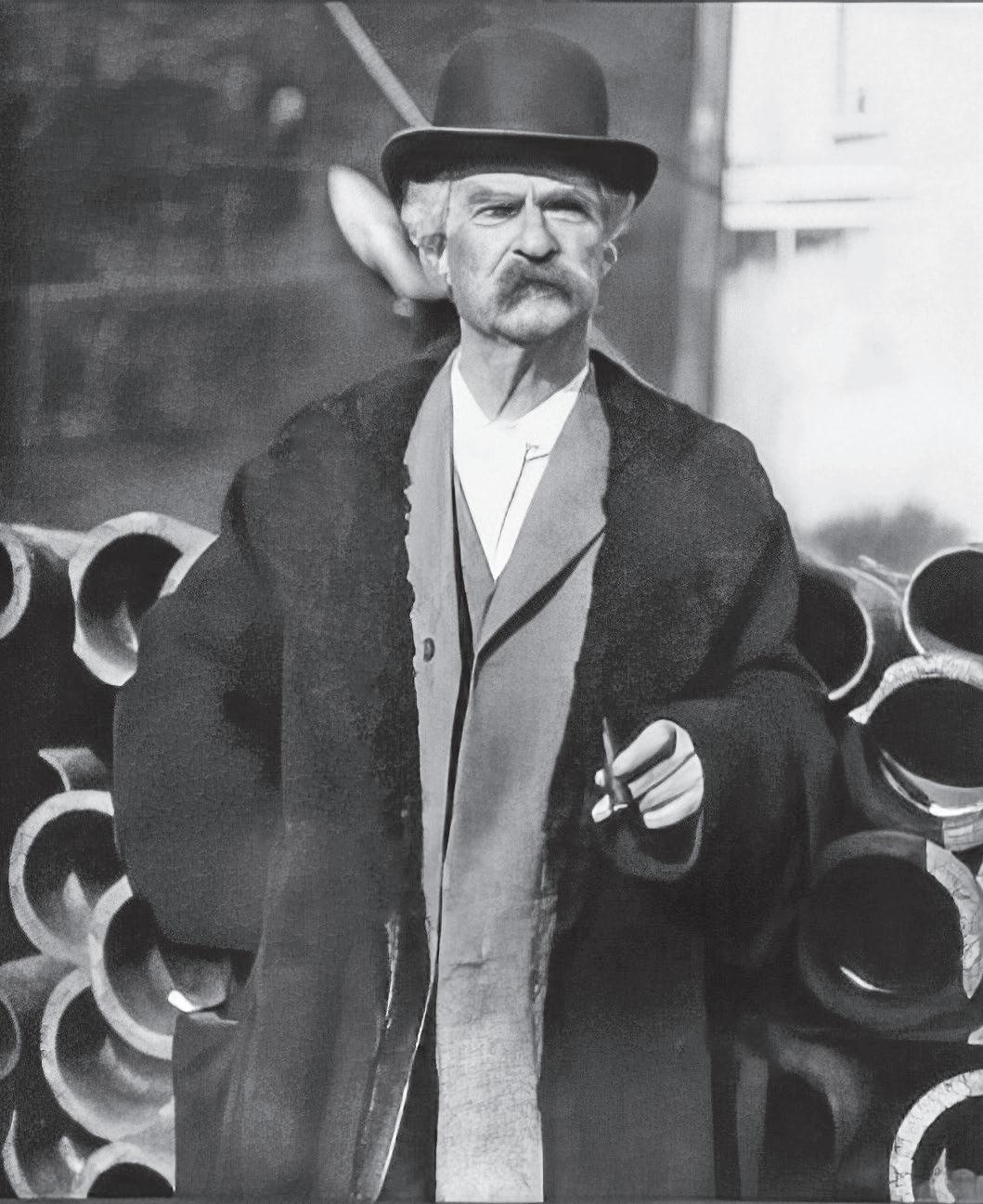

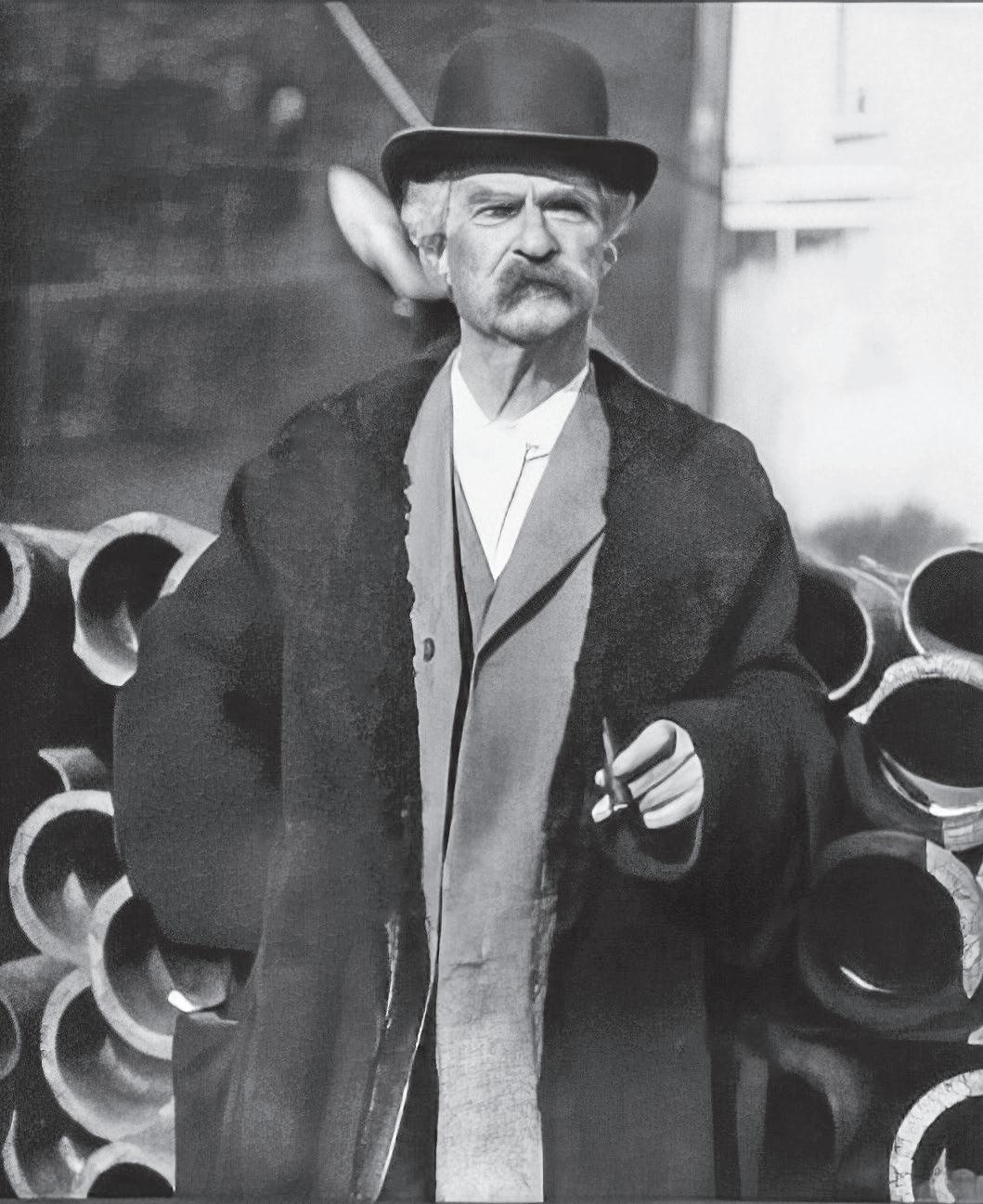

Mark Twain

ALLEN LANE an imprint of

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Allen Lane is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW 11 7BW penguin.co.uk

First published in the United States of America by Penguin Press 2025 First published in Great Britain by Allen Lane 2025 001

Copyright © Ron Chernow, 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN : 978–0–241–77734–3

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

To my parents, who somehow had a crazy faith in their son’s quixotic dream of becoming a writer

Fifteen:

Thirty-Nine: “Stirring

Forty-Four:

Forty-Six: “The

Forty-Seven:

Fifty-Four:

Fifty-Six:

Sixty-Six:

From the time he was a small boy in Hannibal, Missouri, the Mississippi River had signified freedom for Samuel Langhorne Clemens (later known as Mark Twain), a place where he could toss aside worldly cares, indulge in high spirits, and fi nd sanctuary from society’s restraints. For a sheltered, small-town youth, the boisterous life aboard the steamboats plying the river, swarming with raffish characters, offered a gateway to a wider world. Pilots stood forth as undisputed royalty of this floating kingdom, and it was the pride of Twain’s early years that, right before the Civil War, he had secured a license in just two years. However painstaking it was for a cub navigator to memorize the infi nite details of a mutable river with its shifting snags, shoals, and banks, Twain had prized this demanding period of his life. Later he admitted that “I loved the profession far better than any I have followed since,” the reason being quite simple: “a pilot, in those days, was the only unfettered and entirely independent human being that lived in the earth.”

In contrast, even kings and diplomats, editors and clergymen, felt muzzled by public opinion. “In truth, every man and woman and child has a master, and worries and frets in servitude; but in the day I write of, the Mississippi pilot had none.”1 That search for untrammeled truth and freedom would form a defi ning quest of Mark Twain’s life.

For a man who immortalized Hannibal and the majestic river flowing past it, Twain had returned surprisingly few times to these youthful scenes, as if fearful that new impressions might intrude on cherished

memories. In 1875, as he was about to turn forty, he had published in the Atlantic Monthly a seven-part series titled “Old Times on the Mississippi,” which chronicled his days as an eager young pilot. Now, in April 1882, he rounded up his publisher, James R. Osgood, and a young Hartford stenographer, Roswell H. Phelps, and set out for a tour of the Mississippi that would allow him to elaborate those earlier articles into a full-length volume, Life on the Mississippi, that would fuse travel reportage with the earlier memoir. He had long fantasized about, but also long postponed, this momentous return to the river. “But when I come to write the Mississippi book,” he promised his wife, Livy, “then look out! I will spend 2 months on the river & take notes, & I bet you I will make a standard work.”2

Twain mapped out an ambitious six-week odyssey, heading fi rst down the river from St. Louis to New Orleans, then retracing his steps as far north as St. Paul, Minnesota, stopping en route at Hannibal. The three men sped west by the Pennsylvania Railroad in a “joggling train,” the very mode of transportation that already threatened the demise of the freewheeling steamboat culture Twain had treasured. 3 By journeying from east to west, he reversed the dominant trajectory of his life, enabling him to appraise his midwestern roots with fresh eyes. “All the R.R. station loafers west of Pittsburgh carry both hands in their pockets,” he observed. “Further east one hand is sometimes out of doors.”4 Now accustomed to the genteel affluence of Hartford, Connecticut, where he had resided for a decade, he had grown painfully aware of the provinciality of his boyhood haunts. “The grace and picturesqueness of female dress seem to disappear as one travels west away from N. York.”5

To secure candid glimpses of his old Mississippi world, Twain traveled under the incognito of “Mr. Samuel,” but he underestimated his own renown. From St. Louis he informed Livy that he “got to meeting too many people who knew me. We swore them to secrecy, & left by the fi rst boat.”6 After the three travelers boarded the steamer Gold Dust—“a vile, rusty old steamboat”—Twain was spotted by an old shipmate, his alias blown again. Henceforth his celebrity, which clung to him everywhere, would transform the atmosphere he sought to recapture. For all

his joy at being afloat, he carped at the ship’s squalor, noting passageways “less than 2 inches deep in dirt” and spittoons “not particularly clean.” He dispatched the vessel with a sarcasm: “This boat built by [Robert] Fulton; has not been repaired since.” At many piers he noted that whereas steamers in his booming days had been wedged together “like sardines in a box,” a paucity of boats now sat loosely strung along empty docks. 7

Twain was saddened by the backward towns they passed, often mere collections of “tumble- down frame houses unpainted, looking dilapidated” or “a miserable cabin or two standing in [a] small opening on the gray and grassless banks of the river.”8 No less noticeable was how the river had reshaped a landscape he had once strenuously committed to memory. Hamlets that had fronted the river now stood landlocked, and when the boat stopped at a “God forsaken rocky point,” disgorging passengers for an inland town, Twain stared mystified. “I couldn’t remember that town; couldn’t place it; couldn’t call its name . . . couldn’t imagine what the damned place might be.” He guessed, correctly, that it was Ste. Genevieve, a onetime Missouri river town that in bygone days had stood “on high ground, handsomely situated,” but had now been relocated by the river to a “town out in the country.” 9

Once Twain’s identity was known—his voice and face, his nervous habit of running his hand through his hair, gave the game away—the pilots embraced this prodigal son as an honored member of their guild. In the ultimate compliment, they gave him the freedom to guide the ship alone—a dreamlike consummation. “Livy darling, I am in solitary possession of the pilot house of the steamer Gold Dust, with the familiar wheel & compass & bell ropes around me . . . I’m all alone, now (the pilot whose watch it is, told me to make myself entirely at home, & I’m doing it).” He seemed to expand in the solitary splendor of the wheelhouse and drank in the river’s beauty. “It is a magnificent day, & the hills & levels are masses of shining green, with here & there a white-blossoming tree. I love you, sweetheart.”10

Always a hypercritical personality, prone to disappointment, Mark Twain often felt exasperated in everyday life. By contrast, the return to

the pilot house cast a wondrous spell on him, retrieving precious moments of his past when he was still young and unencumbered by troubles. The river had altered many things beyond recognition. “Yet as unfamiliar as all the aspects have been to- day,” he recorded in his copious notes, “I have felt as much at home and as much in my proper place in the pilot house as if I had never been out of the pilot house.”11 It was a pilot named Lem Gray who had allowed Twain to steer the ship himself. Lem “would lie down and sleep, and leave me there to dream that the years had not slipped away; that there had been no war, no mining days, no literary adventures; that I was still a pilot, happy and care-free as I had been twenty years before.”12 One morning he arose at 4 a.m. to watch “the day steal gradually upon this vast silent world . . . the marvels of shifting light & shade & color & dappled reflections that followed, were bewitching to see.”13 The paradox of Twain’s life was that the older and more famous he became and the grander his horizons, the more he pined for the vanished paradise of his early years. His youth would remain the magical touchstone of his life, his memories preserved in amber.

Mark Twain has long been venerated as an emblem of Americana. Posterity has extracted a sanitized view of a humorous man in a white suit, dispensing witticisms with a twinkling eye, an avuncular figure sporting a cigar and a handlebar mustache. But far from being a soft-shoe, crackerbarrel philosopher, he was a waspish man of decided opinions delivering hard and uncomfortable truths. His wit was laced with vinegar, not oil. Some mysterious anger, some pervasive melancholy, fi red his humor— the novelist William Dean Howells once told Twain “what a bottom of fury there is to your fun”—and his chronic dissatisfaction with society produced a steady stream of barbed denunciations.14 Holding nothing sacred, he indulged in an unabashed irreverence that would easily create discomfort in our politically correct age. In a country that prides itself on can- do optimism, Mark Twain has always been an anomaly: a hugely popular but fiercely pessimistic man, the scourge of fools and frauds. On

the surface his humor can seem merely playful—the caprice of a bright, mischievous child—but the sources of his humor are deadly serious, rooted in a profound critique of society and human nature that gives his jokes their staying power.

Mark Twain discarded the image of the writer as a contemplative being, living a cloistered existence, and thrust himself into the hurly-burly of American culture, capturing the wild, uproarious energy throbbing in the heartland. Probably no other American author has led such an eventful life. A protean figure who played the role of printer, pilot, miner, journalist, novelist, platform artist, toastmaster, publisher, art patron, pundit, polemicist, inventor, crusader, investor, and maverick, he courted controversy and relished the limelight. A ferocious bargainer and shameless self-promoter, he sought fame and fortune without hesitation, and established the image of the author as celebrity. In fact, Mark Twain fairly invented our celebrity culture, seemingly anticipating today’s world of social analysts and influencers.

With his inexhaustible commentary, he bestrode a larger stage than any other American writer, coining aphorisms that made him the country’s most- quoted person. He created a literary voice that was wholly American, capturing the vernacular of western towns and small villages where a new culture had arisen, far from staid eastern precincts. Starting with an earthy brand of country humor, he mastered an astonishing variety of literary forms—the novel, short stories, essays, travelogues, burlesques, farces, political tracts, and historical romances—publishing thirty books and pamphlets plus thousands of newspaper and magazine articles. To that he added twelve thousand extant letters written by him or his immediate family, fi fty notebooks crammed with ideas, and six hundred still-incomplete manuscripts.

Whether Twain was our greatest writer may be arguable, if not doubtful, but there’s little question that he was our foremost talker. His oral output—recorded speeches, toasts, and interviews—is no less bountiful than his written record. A nonpareil among platform artists, he spent a lifetime perfecting a beguiling voice that elevated talk into an art form and made audiences yearn for more. For all his erudition, this many-sided

man employed a folksy charm and disarming wit that could appeal to mass audiences. He was so funny that people laughed in spite of themselves, his droll comments slipping past their defenses and shocking them into a recognition of their true beliefs. Even as he railed bitterly against the human race, kicking out the psychological props that sustained it, that race reveled in his biting depictions of its behavior. What any biography of Mark Twain demands is his inimitable voice, which sparkled even in his darkest moments.

No less essential for any life is to capture the massive breadth of Twain’s interests and travels. Not simply the bard of America’s heartland, he was a worldly, cosmopolitan figure who spent eleven years abroad, crossing the Atlantic twenty-nine times. His mind was broadened by an around-the-world lecture tour as well as years of enforced exile in Europe. One of our great autodidacts, he had a far-reaching intelligence that led him to consume history and biography and devour tomes on subjects ranging from astronomy to geology to entomology. Our contemporary recollection of Mark Twain—mostly a sketchy memory of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, and Life on the Mississippi—doesn’t begin to encompass the scope of his interests.

Beyond literature, Mark Twain engaged in an active business life, which was a constant, often damaging, distraction. He raged against plutocrats even as he strove to become one. “All through my life I have been the easy prey of the cheap adventurer,” he confessed sheepishly.15 A compulsive speculator and a soft touch for swindlers, he spent a lifetime chasing harebrained schemes and failed business ventures. His mind would seize upon an idea with an obsessive tenacity that made him oblivious to contrary arguments. Again and again, he succumbed to moneymad schemes he might have satirized in one of his novels. He embodied the speculative bent of the Gilded Age (which he named) with its fondness for new inventions, quick killings, and high-pressure salesmanship.

After his early days in Hannibal, Nevada, and California, Twain reinvented himself as a northeastern liberal, even, at times, a radical. Preoccupied with the notion that only the dead dare speak the truth, he thought our need to make a living turned us all into cowards. There

were some large, controversial topics, such as Reconstruction and the Ku Klux Klan, that he shamefully ducked for the most part. Nevertheless, one is struck by the number of intrepid stands he took. He expressed quite radical views on religion, slavery, monarchy, aristocracy, and colonialism; supported women’s suffrage; contested anti-Semitism; and waged war on municipal corruption in New York. A foe of jingoism, he also took up an array of global issues, including American imperialism in the Philippines, the despotism of czarist Russia, and the depredations of Belgium’s King Leopold II in Africa. Indifferent to politics as a young man, he increasingly emerged as a gadfly and a reformer, acting as a conscience of American society. Even as his novelistic powers faded, his polemical powers only strengthened.

Twain proved fierce in his loves and loyalties. Perhaps his one source of unalloyed happiness came from his intimate relations with his adored wife and three daughters. The cynicism he reserved for others was offset by his implicit faith in Livy—the linchpin of his life—and his deep, if often more complicated, love for his three offspring, Susy, Clara, and Jean. His family life was shadowed by a staggering number of calamities. The saga of the Clemens clan, so full of joy and heartache, lies at the very core of this narrative.

If exemplary in marriage, Twain could be implacable in his hatreds and grudges. A man who thrived on outrage, he had a tendency to lash out at people, often deservedly, but sometimes gratuitously and excessively. He once admitted to his sister that he was a man of “a fractious disposition & difficult to get along with.”16 A master of the vendetta, he would store up potent insults and unload them in full upon those who had disappointed him. He could never quite let things go or drop a quarrel. With his volcanic emotions and titanic tirades, he constantly threatened lawsuits and fi red off indignant letters, settling scores in a life riddled with self-infl icted wounds. Faced with his frequent inability to govern his temper, the gentle, loving Livy tried gamely to tamp down his fury. Mark Twain was often rescued by his wife—she was the necessary ballast of his life—and, consequently, could never quite regain his equilibrium once she was gone.

In our own heightened time of racial reckoning, Twain poses special challenges to biographers and readers alike. Though perhaps the greatest antislavery novel in the English language, Huck Finn has been banned from most American secondary schools, and its repetitive use of the N-word has cast a shadow over Twain’s reputation. Born into a slaveowning family, he transcended his southern roots to a remarkable degree, shaking off most, but never all, of his boyhood racism. No other white American writer in the nineteenth century engaged so fully with the Black community or saw its culture as so central to our national experience. From boyhood, he treated Black people with notable warmth, affection, and sympathy. He experienced tremendous growth in his attitudes, graduating from the crude racist gibes of his early letters and notebooks to a friendship with Frederick Douglass, fi nancing a Black law student at Yale, promoting the Fisk Jubilee Singers, and denouncing racial bigotry in a wide variety of forms. William Dean Howells termed him “the most desouthernized southerner I ever met. No man more perfectly sensed and more entirely abhorred slavery.”17 “Perhaps the brightest side of his whole intellectual career is his progress away from racism,” one scholar has noted, and the statement is true despite some significant lapses.18 From unpromising beginnings, Twain’s striking evolution in matters of racial tolerance will be traced throughout this book.

Twain’s late-life fascination with teenage girls presents yet another disturbing topic for contemporary readers. In many ways a Victorian man, he tended to place women on a pedestal and treated his wife with unfailing reverence. There was never the least hint of scandal in his married life. Yet, after Livy’s death, Twain pursued teenage girls with a strange passion that, while it always remained chaste, is likely to cause extreme discomfort nowadays. Like many geniuses, Twain had a large assortment of weird sides to his nature, and this account will try to make sense of his sometimes bizarre behavior toward girls and women.

To portray Mark Twain in his entirety, one must capture both the light and the shadow of a beloved humorist who could switch temper in a flash, changing from exhilarating joy to deep resentment. He is a fascinating, maddening puzzle to anyone trying to figure him out: charming,

funny, and irresistible one moment, paranoid and deeply vindictive the next. As he once observed ruefully, the “periodical and sudden changes of mood in me, from deep melancholy to half-insane tempests and cyclones of humor, are among the curiosities of my life.”19 Perhaps we should not be surprised that America’s funniest man harbored ineffable sadness and displayed a host of contradictions. In a life of staggering variety, he managed to soar and plunge in emotional extremes. In the last analysis, Mark Twain’s foremost creation—his richest and most complex gift to posterity—may well have been his own inimitable personality, the largest literary personality that America has produced.

Given the fi ne gusto with which Mark Twain flayed hereditary privilege, it seems fitting that he delighted in tracing his paternal ancestry to one Gregory Clement, who had served in the Parliament of England under Oliver Cromwell and joined in signing the death warrant of King Charles I. Twain confessed to being “wholly ignorant” of his forebears but applauded Gregory’s action.1 “He did what he could toward reducing the list of crowned shams of his day.”2 When the monarchy was restored, Gregory was declared guilty of regicide, his severed head posted as a warning atop Westminster Hall. Characteristically, Twain found pungent humor in his fate, declaring that Gregory was “much thought of by the family because he was the fi rst of us that was hanged.”3 Unfortunately, Twain’s descent from Gregory Clement was entirely fictitious, but it was hard to deprive him of a good story with such rich potential for laughter.

The earliest known English ancestor of Mark Twain was Richard Clements of Leicestershire, who lived in the early sixteenth century. In 1642 his great-grandson Robert boarded a ship for the American colonies and aided in founding the town of Haverhill, Massachusetts. Over the years the family drifted south to Pennsylvania and Virginia, where in 1770 it spawned Samuel B. Clemens, grandfather of our author. On October 29, 1797, he married Pamela Goggin in Bedford County in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. In 1742 her grandfather Stephen Goggin, Sr., had emigrated to Virginia from Queen’s County, Ireland.

Samuel and Pamela Clemens, a prosperous young couple, were fully enmeshed in slavery, their ten workers toiling on four hundred acres in Bedford County. The couple brought forth a brood of five children, the eldest being John Marshall Clemens. Born on August 11, 1798, and named after the future chief justice of the United States, John Marshall, he was destined to be the author’s father. When he was seven, his father died in a freak accident—crushed by a falling log during a house-raising—and at some point before adulthood he labored in an iron foundry. Thus robbed of a carefree childhood, he developed a grim, driven personality, with little levity in his nature. He clung to pretensions of supposed descent from the “First Families of Virginia”; what his son labeled “a sumptuous legacy of pride in his fi ne Virginia stock.” Having inherited three enslaved people, he settled in Columbia, Kentucky—his widowed mother had moved to Adair County, near the Tennessee border, and remarried— where he earned a license to practice law.

It was there that he met Jane Lampton, who had grown up in the town. On May 6, 1823, at twenty-four, he married Jane, who was pretty and gregarious, just shy of twenty, and brought a dowry of three more enslaved people. Her father, Benjamin Lampton, was a prominent local citizen, having served as a lieutenant colonel during the War of 1812. As a skilled brick mason, he had constructed many fi ne buildings in town. Jane’s maternal grandfather, William Casey—Indian fighter extraordinaire and Kentucky legislator—was so illustrious that the state named an adjoining county after him. A lively young woman, Jane enjoyed the social opportunities available to the daughter of two prominent families. “During her girlhood Jane Lampton was noted for her vivacity and her beauty,” her eldest son said.4 “She was a great horsewoman when she was young and riding parties were a feature of Kentucky life . . . she was known as the best dancer in Kentucky,” a descendant added. 5 Her famous son would inherit her wealth of red hair as well as her spunk, gift for language, and sprightly spirit.

Jane Lampton proudly claimed ancestry from the British Lambtons of Durham, giving her a dubious connection to a string of earls. As her famous son noted, “I knew that privately she was proud that the Lamb-

tons, now Earls of Durham, had occupied the family lands for nine hundred years; that they were feudal lords of Lambton Castle and holding the high position of ancestors of hers” at the Norman Conquest. 6 Twain later poked fun at this family vanity, especially when one of Jane’s relatives cooked up a preposterous claim to being the genuine Earl of Durham. Such genealogical pretensions would set up Mark Twain as a perfect satirist for big talkers, delusional dreamers, social climbers, and inflated windbags of every description.

The marriage of John Marshall Clemens and Jane Lampton was fated to be a loveless affair, and not solely because of strikingly dissimilar personalities. Jane had been jilted by a young doctor whom she loved and in retribution married John Marshall on the rebound. In a thinly veiled portrait of his father, Twain sketched the tragic consequences: “Stern, unsmiling, never demonstrated affection for wife or child. Had found out he had been married to spite another man.”7 Though his parents behaved in dignified fashion, making a point of mutual courtesy, Twain recalled no signs of outward affection, just a frosty arrangement that substituted handshakes for hugs at bedtime. This arid match would foster in Mark Twain a huge craving for affection in his own marriage.

After a year or two, the newlyweds moved across the border to Gainesboro in northeastern Tennessee. Plagued by headaches and a weak chest, John Marshall Clemens hoped the salubrious mountain air might strengthen his health. Their fi rst son, Orion—pronounced Or -ee-on— was born in 1825, his astral name a reflection of Jane’s taste for the occult. Although John Marshall was an ambitious man, it soon grew apparent that the backwoods hamlet lacked any hint of a future. When Orion visited the cheerless spot more than forty years later, he encountered the “melancholy spectacle of doors closed with signs over them indicating past business; windows broken; houses faded or guiltless of paint.”8

The young family pushed forty miles farther east to Jamestown, in Fentress County, a scenic hinterland of low, rolling mountains called the Knobs, where the career of John Marshall Clemens seemed briefly to flourish. Unlike Gainesboro, this new town breathed an air of possibility,

having recently been named the county seat, and John emerged as a model citizen, serving as the county commissioner and clerk of the circuit court and even taking a hand in building the county courthouse and jail. He erected an impressive house that set envious tongues wagging. With their future more secure, the Clemenses expanded their progeny to include two daughters—Pamela (pronounced Pa- mee-la) born in 1827 and Margaret in 1830—and another son, Benjamin, in 1832; a fi rst son, named Pleasant, died in infancy.

As he strode about town in a blue coat with brass buttons, John Marshall seemed to have satisfied his hunger for respectability. He even branched out into land speculation, amassing virgin forest at a time when real estate could be acquired for less than a penny an acre. Of his total investment, his author son Sam would later bandy about a figure of seventy-five thousand acres, while Orion could only establish title to thirty thousand acres.9 With an overheated imagination, John Marshall daydreamed that his forest of yellow pine would someday yield a cornucopia of iron ore, coal, copper, and timber. This inheritance of the “Tennessee land” would assume mythic proportions in his children’s minds, alternately teasing and tormenting them with hopes of future grandeur. The beckoning mirage of phantom wealth would make ordinary riches seem paltry in comparison. For Sam Clemens, it would breed lifelong fantasies of king-size wealth and countless schemes to attain it. He later pronounced this grim epitaph on the Tennessee land: “It kept us hoping and hoping, during forty years . . . It put our energies to sleep and made visionaries of us—dreamers, and indolent. We were always going to be rich next year—no occasion to work.”10

The time in Tennessee set a tragic pattern for John Marshall Clemens, who would attempt to scratch out a living as a lawyer and public servant only to be forced, for survival’s sake, into the humdrum routine of keeping a store. When his business faltered, he was required to abandon the fi ne house in town—he was now land-rich but cash-poor—and move nine miles north to a secluded spot in the woods, Three Forks, where his family occupied a cramped log cabin, an abrupt comedown from their previous high status in town. This solitary place at the junction of three

rivers preyed on his sociable young wife, who had grown accustomed to material comfort and a buoyant party life in Kentucky. “I had always been in society,” Jane Clemens later complained, and was “very fond of company.”11 In this bleak backwater, John Marshall kept a store and served as the local postmaster at the nearby hamlet of Pall Mall.

In 1834 financial austerity brought on by Andrew Jackson’s clash with the Second Bank of the United States snuffed out John Marshall Clemens’s tenuous standing in Tennessee. Although Sam had not yet been born, the mood of that sudden wreckage must have formed the mental weather of his childhood; the specter of downward mobility shadowed his father, spawning constant status insecurity. As Twain recalled, “From being honored and envied as the most opulent citizen of Fentress county . . . he suddenly woke up and found himself reduced to less than one-fourth of that amount. He was a proud man, a silent, austere man, and not a person likely to abide among the scenes of his vanished grandeur.”12 Stymied by ill luck, battered by hardship, John Marshall became a dour, defeated character, his ambitions thwarted in the wilderness. As Mark Twain wrote, in a character patterned after his father in The Gilded Age, Squire Hawkins was “not more than thirty-five” but with “a worn look that made him seem older.”13 Between the two of them, John and Jane Clemens had inherited six enslaved people, but by the time they left Tennessee, austerity had thinned that number down to one—a young woman named Jennie.

Twice disappointed in Tennessee, John Marshall Clemens uprooted his family again in 1835, piled them into a two-horse carriage, and headed north to Louisville, Kentucky, where they boarded a steamer and rode down the Ohio River to St. Louis. “They had intended to settle in St. Louis, but when they got there they were horrified to hear that a Negro boy had recently been lynched,” one Clemens descendant reported. “Moreover, there was cholera in the city. So they moved on to Florida [Missouri].”14 A more likely story was that the Clemenses had planned to settle in Florida all along since Jane’s brother-in-law, John A. Quarles, had warmly encouraged them to join him there. The new town of Florida, born four years earlier in the state’s northeast corner, stood

on the ragged edge of western settlement. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 had thrown the state wide open to slavery, spurring migration from Kentucky and Tennessee and lending the territory a southern character in the run-up to the Civil War.

Orion recalled their dismal fi rst Florida residence as “a little white frame [house], one-story, with two small rooms, or a room and a shed under the same roof.”15 Since Jane Clemens was pregnant with Sam during the westward journey, Orion would tease his brother that this early “travel had something to do with your roving disposition.”16 With as sharp a tongue as her famous son, Jane Clemens later derided the frail house as “too small for a baby to be born in,” yet she gave birth, two months prematurely, to Samuel Langhorne Clemens on November 30, 1835. The baby was named after his paternal grandfather, while John Marshall Clemens supplied the middle name in homage to a boon companion from his Virginia youth. With a flair for showmanship, mother and son converted Sam’s birth into a cosmic event, marked by the appearance of Halley’s Comet, which revisits the Earth at seventy-fiveyear intervals. Later endowed with a quip for every occasion, Twain remarked of his birth: “The village contained a hundred people and I increased the population by 1 per cent . . . There is no record of a person doing as much—not even Shakespeare.”17

At a time of rampant infant mortality, the baby proved a runt with a sickly nature, and his parents grew concerned. “When I fi rst saw him [I] could see no promise in him,” Jane admitted in afteryears. “But I felt it my duty to do the best I could . . . But he was a poor-looking object to raise.”18 When she was in her eighties, her son asked about his troubled infancy. “I suppose that during all that time you were uneasy about me.” “Yes, the whole time,” she agreed. Twain persisted: “Afraid I wouldn’t live?” With a perfect deadpan worthy of her son, Jane retorted, “No, afraid you would.”19

Mark Twain would lampoon “the almost invisible village of Florida,” evoking a settlement of two unpaved streets and scattered lanes. “Both the streets and the lanes were paved with the same material—tough black mud, in wet times, deep dust in dry.” With fl imsy houses made of logs,

even the church was propped up on timber, allowing local hogs to root around underneath and squeal noisily during services. John Marshall entered into a partnership with John Quarles in a dry goods shop that sold a bit of everything: calico and coffee, shovels and brooms, hats and bonnets, even offering a swig of corn whiskey to every customer. Because John Marshall was a rigid man, he didn’t cotton to the easygoing ways of John Quarles. Soon the partnership was dissolved and Clemens set up a rival store across the street.

As in Tennessee, John Marshall Clemens strove to lift a nascent town from obscurity and set it on the high road to progress. A political Whig, with an abiding faith in internal improvements, he was appointed president in 1837 of the Salt River Navigation Company, assembled to dredge the nearby river and open it to steamboat commerce from the Mississippi River. He was likewise made a commissioner of the Florida & Paris Railroad, both projects wiped out by the Panic of 1837 and a dearth of political support. John Marshall did land one coveted accolade: he was named a judge of the Monroe County Court, forever after bearing the proud title of Judge Clemens. He traded up to a larger house—three rooms and a kitchen—where Sam Clemens’s beloved younger brother, Henry, was born in 1838.

The following year, Twain’s sister Margaret died at age nine of a bilious fever. One day she returned from school in a delirious state and lay dead within a week. Jane Clemens always maintained that the girl “was in disposition & manner like Sam full of life” and enjoyed taunting her sister, Pamela. 20 As she lay dying, Sam glided fast asleep into her room one night and stroked her bedclothes, exhibiting the somnambulism that would mark his childhood. Perhaps, if informed of the episode, it was his first intimation that he harbored an inner self free from his conscious control—a spiritual twin—which would form a recurrent theme in his later writings.

The next year Judge Clemens concluded that the tiny village of Florida would never shake off its rustic slumber. Once again he had hitched his luckless fate to a dying town. In Mark Twain’s mordant view, “He ‘kept store’ there several years, but had no luck, except that I was born to

him.”21 When Sam was nearly four in 1839, the judge turned his eyes to the Mississippi port town of Hannibal, thirty-five miles to the northeast. Then a raw and relatively new country town with a vigorous, enterprising people and a diversified economy, Hannibal was a thriving metropolis compared to Florida. It already had the hallmarks of a genuine town, including sawmills, blacksmith shops, saloons, and a distillery. A fastgrowing commercial hub, it exported wheat and tobacco harvested from inland farms while drovers herded swine through its streets to two slaughterhouses. As Orion later observed in the town paper, “Our people have a horrid aversion to the jury box and the witnesses’ stand. They greatly prefer the study of pork and flour barrels, tape, cordwood, and the steamboat’s whistle.”22 For Sam Clemens, the move to Hannibal was monumentally important, for it is impossible to picture his career without the front-row seat that Hannibal afforded for the abundant traffic steaming by on the Mississippi River.

After selling his farm acreage and house in Florida, Judge Clemens plowed the proceeds into purchasing a cluster of buildings in downtown Hannibal, including a corner hotel at the foot of sloping Hill Street, where his family first lived. He commenced yet another general store, facing the nearby Mississippi wharves, and stocked it with dry goods and groceries bought on credit from St. Louis merchants. The teenage Orion, clad in a brand-new suit of clothes, worked as a clerk. By autumn 1841, the judge’s congenital bad luck and poor head for business ushered in yet another commercial collapse as economic conditions exhausted his credit in St. Louis. Orion remembered the store’s chief creditor ruthlessly stripping the shelves bare for repayment—“all the dry goods, groceries, boots and shoes and hardware in his store”—so that his father “began his fi rst acquaintance with poverty.”23 To help support the family, a resentful Orion was apprenticed to the Hannibal Journal before being shipped off to St. Louis to work as a printer.

The embarrassment of ingrained failure must have seeped deep into the pores of John Marshall Clemens. Snappish, moody, and temperamental, he wasn’t the sort to be amused by the comic relief of his son Sam’s compulsive pranks and mischief. His few surviving letters portray a man

riddled with anxiety and ground down by monetary stress; they are devoid of gaiety, charm, or humor. To raise cash in 1842, he traveled down the Mississippi and sent home a letter that reeked of desperation. “I do not know yet what I can commence at for a business in the spring. My brain is constantly on the rack with the study, and I can’t relieve myself of it—The future taking its complexion from the state of my health, or mind, is alternately beaming in sunshine, or overshadowed with clouds; but mostly cloudy, as you will readily suppose.”24 When he got home and Jane berated him for the costly but fruitless trip, John Marshall pleaded that he meant well, saying plaintively, “I am not able to dig in the streets.” Orion always remembered the “hopeless expression of his face.”25

Adding to the fatalistic mood, Benjamin Clemens, nearly ten, died on May 12, 1842, and his parents’ grief was so profound that Orion saw them kiss for the fi rst time. The experience disclosed to Sam the depths of emotional pain bottled up inside Jane Clemens. As she and Sam knelt beside the dead boy stretched on the bed, she erupted in tears and moans of “dumb” sorrow that startled her son. “The mother made the children feel the cheek of the dead boy,” Sam recalled, “and tried to make them understand the calamity that had befallen.”26 Childhood mortality, however commonplace, was still exquisitely painful for parents. This was the third child John Marshall and Jane Clemens had lost, and the harrowing scene was forever lodged in the memory of Sam Clemens, who, for some nameless reason, believed he had treacherously betrayed his dead brother. There was both nobility and futility in the striving of Judge Clemens, who could never establish abiding security for his family and exhibited the bone-deep fatigue of a desperate man. Orion spoke of irritability from “disordered nerves” as he strained to fi nd his elusive niche in the world. 27 His fortunes rebounded modestly as he picked up fees from practicing law, and around 1844 was named Justice of the Peace, which meant settling civil complaints and lawsuits over debt. He also oversaw slavery disputes and twice ordered lashes meted out to enslaved offenders. In his humble courtroom, he sat squarely on a three-legged stool, with dry goods boxes serving as his desk, rapping out decisions with a mallet and recording them with “his sharp pen,” recalled Orion. 28 Though a

respectable man, Judge Clemens could be forbiddingly humorless, the antithesis of the waggish Sam. One newspaper painted him thus: “He was a stern unbending man of splendid common-sense . . . the autocrat of the little dingy room on Bird Street, where he held his court . . . and preserved order as best he could in the village.”29 With his fi nances in somewhat better shape, Judge Clemens constructed a house for his family on the steeply inclined Hill Street, a two-story white frame, narrow but deep, with Sam likely occupying the last bedroom on the upper floor. Outside stood a certain fence that would be immortalized in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer.

From a fictional portrait Twain wrote of his father, we know that he was tall and lean with lank black hair drooping to his shoulders, showed “courtly, old-fashioned” manners, and was impeccably honest. 30 He scrupulously adhered to social convention and got precious little for it. Oppressed by worry, his face unsmiling, he walked the streets with such extreme formality that he cringed when someone accosted him and slapped his back. His scholarly bent made him a stickler for grammar— he shipped Orion an entire course of twenty lessons on the subject—and he presided as president of the Hannibal Library Institute. Hannibal’s citizenry viewed him with respect, not warmth, and nicknamed him “Squire,” suggestive of his superior airs. A local minister claimed he was “a grave, taciturn man, a foremost citizen in intelligence and wholesome influence.” A local school principal called him “never a practical man, but an energetic dreamer . . . courteous, well-educated . . . a good conversationalist.”31 For all his moralistic zeal, Judge Clemens shied away from church attendance, and this may be the one trait that endeared him to Sam and influenced his later freethinking ways.

The father who found humor in nothing spawned a son who found humor in everything. It is easy to see how the aloof Judge Clemens, who hated disorder and was emotionally remote, produced a rebellious, devilmay- care son and left him with an enduring ambivalence toward authority figures. At thirty-four, Mark Twain recalled the “judicial frigidity” of a father who could discover no charm in his juvenile antics. Never cruel toward his children, John Marshall nonetheless threw a distinct

chill in the air around him. As Twain said, he was “ungentle of manner toward his children,” though he “never punished them—a look was enough, and more than enough.” Father and son circled each other warily. “My father and I were always on the most distant terms when I was a boy—a sort of armed neutrality, so to speak.”32 Another time Twain said that “my own knowledge of him amounted to little more than an introduction.”33 He remembered only a single time when his father hazarded a joke. They had come upon a room full of loaves of bread moldy with blue cobwebs, and the startled boy asked where they came from. “From Noah’s Ark,” the judge responded. 34 Curiously enough, it is a very Mark Twain line. If there is a source of the rage that informed Mark Twain’s career, it probably originated with a repressed fear of his father, whom he never dared to confront directly. Instead that rage expressed itself indirectly, played out in boyhood hijinks and a cynical defiance toward elders. Humor proved a survival strategy with a humorless father. Where Judge Clemens gravitated to the safety of courts, railroads, and libraries, his son would become a confi rmed renegade against institutions and pride himself on a wild, lawless streak.

Luckily, with her joie de vivre, Jane Lampton Clemens provided compensatory warmth and brightness in her son’s life. From her he derived all his emotional sustenance. Slim and pretty, with the erect carriage of a dancer and keen blue eyes, she moved through her day with good-humored energy and was a popular figure around town. If Sam carried the Clemens name, he clearly manifested the Lampton genes. “He is all ‘Lampton,’ ” Orion’s wife, Mollie, said, “and resembles his mother strongly in person as in mind.”35 Mother and son bore a comical resemblance, especially in their sharp but slightly melancholy eyes and exaggerated drawls. From his mother Sam inherited a storytelling passion and an insatiable curiosity about people. However kindly she was, Jane Clemens also exhibited a certain midwestern reserve, never kissing her children and maintaining a ladylike sense of propriety. Her puritanical side was observed by her son on a trip to New Orleans as a teenager. “Ma was delighted with her trip, but she was disgusted with the girls for allowing me to embrace and kiss them.”36

With tender solicitude, Jane Clemens watched Sam perpetrate one outrageous prank after another. She adored but was bemused by this wayward son, taking an exasperated pride in his constant skylarking. He captured her ambivalence in his affectionate portrayal of Aunt Polly in Tom Sawyer. “My mother had a good deal of trouble with me,” Mark Twain confessed, “but I think she enjoyed it.”37 Even as he got older, Twain relished prodding and teasing her, much like Tom with Aunt Polly. Whenever Jane, with a straight face, lectured Sam for some misdeed, he would rebut her with an unexpected witticism that made her break down in laughter. Early on she recognized his instinctive tendency to embellish the truth, and though she made an effort to quash it, she came to accept him on his own terms. “I discount him ninety per cent,” she remarked of Sam’s tall tales. “The rest is pure gold.”38 From his mother, Mark Twain learned that he could trust women and express a richer spectrum of emotion than with men. With his father, Sam had to suppress his personality; with his mother, he could flaunt it.

With her broad sympathies, Jane Clemens was likely to spy redeeming traits even in hardened sinners and outcasts. As her son expressed it, she had the “larger soul that God usually gives to women.”39 Despite struggles with her husband and the death of several children, she kept darkness at bay with a ready friendliness, her high-spirited and funloving nature reflected in her passion for the color red. “Grandma’s room was always a perfect riot of red; carpets, chairs, ornaments, were all red,” said a granddaughter. “She would have worn red, too, if she had not been restrained.”40 “She was of a sunshine disposition,” agreed Twain, “and her long life was mainly a holiday for her. She always had the heart of a young girl.”41 Jane flocked to spectacles: circuses, Fourth of July parades, theatrical performances, and church revivals, and she boasted of never skipping a funeral. To those mystified by her fondness for funerals, she explained that “if she didn’t go to other people’s funerals they wouldn’t go to hers!”42 Sam’s life would reflect his mother’s love of pageantry. Her curiosity was also piqued by anything that savored of the occult, spirituality, or mysticism.

Another area where Jane Clemens left a profound imprint on her au-

thor son lay in the realm of language. She wasn’t literary or sophisticated, and read little beyond Bibles and newspapers, yet she had a plainspoken eloquence when protesting injustice or indulging in pathos. She preferred short, simple words and flavored her conversation with banter in a way reminiscent of her son. A natural raconteur, she could spin large tales by embroidering scanty facts. When Twain later said his mother had “the ability to say a humorous thing with the perfect air of not knowing it to be humorous,” he described his own trademark technique.43 From her he also learned how the right manner could make the matter more affecting. In a story called “Hellfi re Hotchkiss,” he sketched this picture of Jane as a speaker, saying, “there was a subtle something in her voice and her manner that was irresistibly pathetic, and perhaps that was where a great part of the power lay; in that and in her moist eyes and trembling lip. I know now that she was the most eloquent person I have met in all my days, but I did not know it then.”44 Often Jane Clemens was inadvertently funny. When a distraught neighbor informed her that a man had died when a calf raced in front of him, throwing him from his horse, Jane responded unexpectedly, “What became of the calf?”45

Jane Clemens communicated to her son a deep love of animals, most notably cats. Unable to resist strays, she at one point had collected nineteen cats, a fondness for animals that moved her granddaughter to protest, “Grandma, I believe you like cats better than babies.” A bit miffed, Jane defended her behavior: “When you’re tired of a cat you can put it down.”46 She would never swat a fly, punished cats sneaking off with mice, and forbade caged pets in her household. As Twain put it, “An imprisoned creature was out of the question—my mother would not have allowed a rat to be restrained of its liberty.”47 This sympathy for living creatures would be amply reflected in the animal rights activism of her son and granddaughters.

Mark Twain retailed stories of his mother’s bravery in standing up for the oppressed, how she blocked a Corsican father pursuing his grown daughter with a rope and scolded a St. Louis driver lashing his poor horse. She also showed sympathy for the enslaved of Hannibal that never extended to outright criticism of the institution itself. At one point, the

Clemenses hired for housework an enslaved boy, Sandy, whose incessant singing drove Sam (always hypersensitive to noise) to distraction. When he complained to his mother, she lectured him in terms of simple humanity. “Think; he is sold away from his mother; she is in Maryland, a thousand miles from here, and he will never see her again, poor thing. When he is singing it is a sign that he is not grieving . . . it would break my heart if Sandy should stop singing.”48

Yet this same Jane Clemens could mistreat their house slave, Jennie, tended to badmouth “Yankees,” and grumbled about “black Republicans.”49 When Twain attempted to trick Jane and her friend Betsey into staying at a Black minstrel show in St. Louis, saying they would hear African missionaries, the ladies were not amused by the stunt. Instead, they “began to question the propriety of their countenancing the industries of a company of negroes, no matter what their trade might be.”50 Because Hannibal was a slave-owning town, its institutions all conspired to certify the justice and legality of involuntary servitude. “Kindhearted and compassionate as she was,” Twain reflected of his mother, “I think she was not conscious that slavery was a bald, grotesque, and unwarranted usurpation . . . As far as her experience went, the wise, the good, and the holy were unanimous in the belief that slavery was right, righteous, sacred, the peculiar pet of the Deity, and a condition which the slave himself ought to be daily and nightly thankful for.”51 Few, if any, contrary voices were heard on Hannibal’s streets, and children were taught to dread abolitionists as sinister bogeymen who preyed on Godfearing, slave-owning folk. That the compassionate Jane Clemens could be trained to regard slavery as a humane system instead of a monstrosity would serve as an object lesson for Mark Twain in the terrifying power of environment to shape and distort human behavior.

While Twain maintained that his father opposed slavery in principle, deeming it “a great wrong,” it is difficult to square that with his actions. 52 In September 1841, John Marshall Clemens served as foreman on a jury that convicted three abolitionists who had crossed the Mississippi to emancipate five slaves, and they were sentenced to twelve years’ hard labor. The following year, during the Mississippi River trip that so upset

Jane Clemens, Judge Clemens tried to scrounge up money by selling a Black man named Charley for “whatever he will bring where I take water again, viz, at Louisville or Nashville.”53 Reading this letter late in life, Mark Twain was dismayed by the sickening way his father talked about the man as if he were “an ox—and somebody else’s ox. It makes a body homesick for Charley, even after fi fty years.”54 Even when Judge Clemens did not own enslaved people, he rented them from others.

As the years passed and darker truths about slavery surfaced in his memory, Twain remembered savage punishments infl icted upon the Black population and how such cruelty was so embedded in the society that nobody protested or even seemed to notice. In 1896, while traveling in India, Twain recorded how his father had struck him only twice in childhood, yet “he commonly cuffed our harmless slave boy Lewis for any little blunder or awkwardness, even gave him a lashing now & then, which terrified the poor thing nearly out of his wits. My father passed his life among the slaves from his cradle up, & his cuffi ngs proceeded from the custom of the time, not from his nature.”55

The following year, while summering in Switzerland, Twain had another flashback of how his father had brutalized the enslaved Jennie, who had nursed the Clemens children. As Jane Clemens was about to whip her for insubordination, Jennie dared to grab the whip from her hand, and Judge Clemens was promptly summoned. “Judge whipped her once, for impudence to his wife—whipped her with a bridle.”56 It may have been this notorious act of cruelty that led Jennie to plead for what was commonly seen as the worst punishment: to be sold down the river by a hated slave trader named William Beebe, who had, said Twain, beguiled “her with all sorts of fi ne and alluring promises.”57 Jane consented to this and persuaded her husband, who badly needed the money. Mark Twain remembered that the sale of Jennie was “a sore trial, for the woman was almost like one of the family.”58 Years later, he saw Jennie working as a chambermaid on a steamboat and she “cried and lamented.”59 Such barbarism toward Blacks was Hannibal’s underlying reality, and Twain would spend the rest of his life seeking to acknowledge and understand how people could have accepted it.

In later years, yet another terrifying memory of slavery surged to the forefront of Mark Twain’s mind: “When I was 10 I saw a man fl ing a lump of iron ore at a slaveman [sic] in anger—for merely doing something awkwardly, as if that were a crime. It bounded from his skull & the man fell & never spoke again. He was dead in an hour. I knew the man had a right to kill his slave if he wanted to, and yet it seemed a pitiful thing and somehow wrong . . . Nobody in the village approved of that murder, but of course no one said much about it.”60 Mark Twain registered these fleeting impressions as a boy, but only with the benefit of hindsight would he fully fathom their true horror.

In his fiction, Mark Twain would memorably evoke Hannibal as “the white town drowsing in the sunshine of a summer’s morning,” a place where it never seemed to snow despite fierce Missouri winters.1 He presented it as an earthly paradise where youngsters went barefoot in summer and gorged on cornmeal cakes and catfish. “Well, it was a beautiful life, a lovely life,” he once told a dinner audience in his drollest vein. “There was no crime. Merely little things like pillaging orchards and watermelon patches and breaking the Sabbath—we didn’t break the Sabbath often enough to signify—once a week perhaps.”2 The town’s children may have been poor, but they didn’t know it. “To get rich was no one’s ambition—it was not in any young person’s thoughts . . . It was an intensely sentimental age, but it took no sordid form.”3 He argued that the California gold rush in 1848, when he turned thirteen late in that year, introduced “the lust for money which is the rule of life to- day, and the hardness and cynicism which is the spirit of to- day.”4 He forever remembered the cavalcade of eager townspeople streaming westward in canvas- covered wagons—“We were all there to see and to envy”—and even the local schoolteacher, John D. Dawson, flocked to join the exodus with the money-hungry horde. 5

That Twain could portray his boyhood in such sunlit terms shows the extent to which his frolics with friends enabled him to escape the grueling insecurity of family life and his father’s fi nancial woes. The carefree sprees stood in stark contrast to the gloom that enveloped his household,

and he later traced his dread of debt to the monetary setbacks the Clemens clan endured. Fifty years later, he could still summon up, beneath the air of nostalgia, the “sordidness and hatefulness and humiliation” of those early days. 6

Even as a boy, Sam Clemens had a pronounced streak of nonconformity—he hated being hemmed in by social rules—expressed in constant clowning as he mocked the conventional piety of the townspeople. “Sam was always full of fun,” said one cousin. “He could play more pranks and escape with less punishment than anybody I ever knew.”7 With his intelligence concealed behind a mask of insouciance, he revolted against schoolhouse discipline and rote learning and Jane Clemens’s valiant efforts to tame him. She recollected: “Sam was always a good-hearted boy, but he was a very wild and mischievous one, and do what we would we could never make him go to school. This used to trouble his father and me dreadfully, and we were convinced that he would never amount to as much in the world as his brothers, because he was not nearly so steady and sober-minded as they were . . . Finally his father and the teacher both said it was of no use trying to teach Sam anything, because he was determined not to learn.”8 In many ways, he was a lazy boy, disorganized and easily bored, always craving novelty, but he could focus intensely on things that dearly interested him—especially outside the schoolhouse.

In the manner of all autodidacts, Sam Clemens educated himself by reading from passion, not duty. He retained his boyhood fondness for The Adventures of Robin Hood, both the “quaint & simple . . . fragrant & woodsy England” as well as its characters, “the most darling sweet rascals that ever made crime graceful in this world.” 9 He and close friend Will Bowen would “undress & play Robin Hood in our shirt-tails, with lath swords, in the woods on Holliday’s Hill on those long summer days.”10 Confi ned in the remote little town, Sam escaped into the faraway exploits of Robinson Crusoe, The Arabian Nights, and The Count of Monte Cristo, which gave intimations of the boundless world “curtained away” beyond Hannibal.11

This willful boy had a penchant for doing shocking things, whether

teasing girls with garter snakes or leaving dead bats for his mother to find. With his friends he rolled a giant boulder dangerously down Holliday’s Hill, fed a tobacco plug to a visiting elephant, and jumped off a ferry into the river. With pardonable exaggeration, he claimed that he had nearly drowned nine times in the Mississippi River or Bear Creek, and on one occasion remembered an enslaved woman grasping his wriggling fi ngers and fishing him free from the water. Sam was a sweet burden to Jane Clemens, who nursed him back to health. “I guess there wasn’t much danger,” she warned him. “People born to be hanged are safe in water.”12

Sam’s reputation as a trickster and troublemaker likely came from a desire to be noticed; being funny was the best way to attract boys, impress girls, and ward off his father’s looming presence. “Celebrity is what a boy or a youth longs for more than for any other thing,” he observed in his Autobiography. “He would be a clown in a circus; he would be a pirate, he would sell himself to Satan, in order to attract attention and be talked about and envied.”13 Later on he came up with an aphorism: “There are no grades of vanity, there are only grades of ability in concealing it.”14 The naughty child grew up to be the naughty adult author, with the same ceaseless need to attract attention by spouting scandalous commentary. The older Mark Twain pointedly noted that the “appetite for notice and notoriety” had lingered in his adult life.15

Twain was fond of recounting a story about a measles epidemic that swept Hannibal when he was ten, killing many children. He was so steeped in fear that he decided to end the suspense by contracting the disease on purpose. So he sneaked into the bed of a friend with measles and duly came home with the disease. Far from suffering, Sam Clemens found the situation “most placid and tranquil and sweet and delightful . . . I was the centre of all this emotional attention and was gratified by it and vain of it.”16

Early on the boy learned that he could monopolize people’s attention and cast a hypnotic spell thanks to his unusual facility with language. When her granddaughter once asked Jane Clemens what distinguished Sam from other children, she said that “when he had gone anywhere, if only downtown, when he came home all the children would gather

around to hear what he had to tell. He knew even then how to make things interesting. She also said that when she saw a crowd running, she didn’t ask what was the matter, but ‘what has Sam done now?’ ”17

If Sam excelled at taunts, sometimes showing flashes of cruelty, he was also credited with a warm heart, a mixture of moods that persisted into adulthood. Orion praised his younger brother as “a rugged, brave, quick-tempered, generous-hearted fellow,” with an outsize “capacity of enjoyment . . . and of suffering” who felt “the utmost extreme of every feeling.”18 Like Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn, Sam exhibited an outlaw spirit, preferring to tarry on the fringes of town, Holliday’s Hill and McDowell’s Cave, but most of all on the river with its mysterious, isolated islands, where he gloried in a sense of freedom. On Glasscock’s Island, Sam and his comrades fished and swam, searched for turtle eggs, and smoked corncob pipes. He was especially enamored of a guttersnipe named Tom Blankenship, who resided a block from his home in a rude dwelling dark with poverty. A master of petty thefts, especially of turkeys and onions, Tom was scruffy and dirty, a stranger to baths and schools, and thoroughly happy despite being the son of the town drunkard. Tom’s company was forbidden to Sam, which greatly enhanced his appeal. In Sam’s view, Tom was “the only really independent person— boy or man—in the community.”19 This fascination with marginal and taboo figures previews the radical vision of Twain’s fiction in which he found virtue in the low born and vice in the well bred, lending a dark glamour to boys who flouted parental strictures.

Mark Twain was born with a natural attraction for the disapproved thing. “There is a charm about the forbidden that makes it unspeakably desirable,” he wrote. “It was not that A[dam] ate the apple for the apple’s sake, but because it was forbidden.”20 A self-styled enfant terrible, he began to smoke by age eight, a habit that remained surreptitious while his father was alive. He believed devoutly in his later aphorism “Few things are harder to put up with than the annoyance of a good example.”21 He could never abide obedient, apple-polishing classmates who toadied to parents, teachers, and preachers, and he reserved a special animus for Theodore Dawson, the schoolteacher’s son. “In fact he was inordinately

good, extravagantly good, offensively good, detestably good—and he had pop-eyes—and I would have drowned him if I had had a chance.”22 His hatred for these model boys came from a feeling that they were priggish and empty, all show but no substance in their subservience.

If Hannibal was a sleepy town, it was galvanized into startling life twice daily by the arrival of a steamboat either traveling upriver from St. Louis or down from Keokuk, Iowa. The boat would paint a distant spot of black smoke in the sky that was usually noticed fi rst by a Black drayman who uttered a jubilant cry: “S-t-e-a-m-boat a- comin’!” In Life on the Mississippi, Twain reported the tonic effect on the town. “The town drunkard stirs, the clerks wake up, a furious clatter of drays follows, every house and store pours out a human contribution, and all in a twinkling the dead town is alive and moving.”23 From the steamboat issued everything from carriages to traveling salesmen to minstrel shows to itinerant circuses. Sam Clemens enjoyed instant access to this excitement: he simply had to exit his Hill Street house, turn left, and there, just a block or two away, lay the vast, shining Mississippi, three- quarters of a mile wide, looking especially magnificent with a steamboat moored at the dock. From Holliday’s Hill, three hundred feet up, he could obtain panoramic, unobstructed views of the river as it meandered through the rich flat farmland in northeast Missouri and western Illinois.

The daily advent of the steamboats planted the fi rst ambition that took root in Sam Clemens: to be a pilot. He craved attention, and nobody drew more than the pilot, who wore fancy duds and enjoyed an “exalted respect” as he strutted about town. 24 Of no less interest was the “princely salary” that the pilot pocketed each month: “Two months of his wages would pay a preacher’s salary for a year.”25 The river held many wonders beyond steamboats, especially the annual arrival of a massive fleet of rafts floating to markets downriver with “an acre or so of white, sweet-smelling boards in each craft,” manned by “a crew of two dozen men or more.”26 Sam and his friends would plunge into the river, swim to the rafts, and hitch a thrilling ride.

In the meantime, the future author had to suffer through something called school, which he viewed as the centerpiece of an unspoken adult

conspiracy to deprive children of fun. At age four he trudged off to a private school run by Elizabeth Horr, who commenced class with a prayer and a New Testament selection. On his fi rst day, Sam, the class clown, got into trouble and was punished with strokes from a switch. He would attend three private schools, one a log schoolhouse with girls on one side, boys on the other, and wrote scornfully of “what passed for a school in those days: a place where tender young humanity devoted itself for eight or ten hours a day to learn incomprehensible rubbish by heart out of books and reciting it by rote, like parrots.”27 Restless in school, a born truant, he yearned on warm days for the barefoot freedom of the surrounding countryside. Perhaps this scanty education enabled him to develop a literary voice that was fresh and original, unspoiled by any European or Eastern Seaboard influences.

The most-perceptive observations of young Sam Clemens came from a very pretty girl named Laura Hawkins, who lived directly across Hill Street but in a more imposing house, which signaled a step up the economic ladder, her father having owned a large mill and slave plantation further inland. She would figure as the model for Becky Thatcher in Tom Sawyer. Twain sentimentalized her as his fi rst sweetheart and never lost his soft spot for her. At age five, he said, “I had an apple, & fell in love with her & gave her the core.”28 Her fi rst glimpse of her attentiongrabbing young neighbor was indelible: a barefoot boy who “came out of his home, opposite mine, and started showing off, turning handsprings and cutting capers just as described in Tom Sawyer.” Sam had “long golden curls hanging over his shoulders at the time.”29 His comic persona, she saw, concealed a sensitive boy of natural refi nement, who was “gentle . . . and kind of quiet,” with a conspicuous drawl reminiscent of his mother. 30 Even though Sam “played hooky from school” and “cared nothing at all for his books . . . I never heard a coarse word from him in all our childhood acquaintance.”31

From his first encounter with the female sex, Sam Clemens was courtly and gallant, as in future years. “He used to carry my books to school every morning,” recalled Laura, “bring them home for me in the afternoon, and occasionally he would treat me to apples, oranges and such

things, or divide his candy with me.”32 From Sam, she must have heard the family saga of past Virginia gentility—aristocrats down on their luck—for she noted that the Clemenses “came from very fi ne stock, but were very poor.”33 Appreciative of his special humor, she noted his ability to discern the absurdity in situations and said his success in telling a funny story lay not so much in its content than in his “drawling, appealing voice.”34

School wasn’t the only adult institution that Sam Clemens had to put up with: the Church also conspired against the pleasures coveted by small boys. In later years, Mark Twain came to believe that the creation of humanity, with its deeply flawed nature, was nothing for the Lord to boast about and would inveigh against “the superstitions in which I was born & mistrained.”35 That perspective came later. In Hannibal, atheists were about as popular as abolitionists, and Sam’s boyhood was saturated with religious training. By age twelve he was steeped in the Old and New Testaments, which left their mark on his writings. While the skeptical John Marshall Clemens evaded church services, Jane Clemens was a fervent Presbyterian, and Sam was affected by all the fi re-and-brimstone sermons about the afterlife. As he phrased it, “The Presbyterian hell is all misery; the heaven all happiness.”36 So far did early religious experience permeate his mind that heaven and hell became lifelong fi xtures in his humorous repertoire, with Satan his best comic character. The only profession that ever vied with piloting in Sam Clemens’s fantasy life was that of becoming a preacher, which seemed a sure way to forestall damnation. “It looked like a safe job,” he confi rmed. 37 Another time he confessed about being a preacher that he lacked “the necessary stock in trade—i.e., religion.”38

Though he suffered through services in the Presbyterian church with its high pulpit, Bible on a red plush pillow, and congregants sitting in stiff pews, he still regarded himself as an incorrigible sinner, headed straight to hell. Every time a boy in town drowned, Sam chalked it up to an angry deity who was coming for him next. Although he consoled himself by day, saying God would be patient, dark fears of retribution sneaked up on him at night. “With the going down of the sun my faith

failed, and the clammy fears gathered about my heart. It was then that I repented. Those were awful nights, nights of despair, nights charged with the bitterness of death.”39

One thing, in retrospect, that weakened Mark Twain’s faith in the church of his childhood was its unswerving endorsement of slavery. The evidence of slavery’s misery stood scattered all around him—“the saddest faces” Sam Clemens ever saw were those of a dozen shackled slaves on Hannibal’s dock awaiting shipment farther south—but he heard no condemnation from religious leaders.40 Nearly half the families in Marion County held at least one person in bondage, almost invariably with a clear conscience. “In my schoolboy days,” Twain said, “I had no aversion to slavery . . . the local pulpit taught us that God approved it, that it was a holy thing, and that the doubter need only look in the Bible if he wished to settle his mind.”41 Beyond preaching slavery, pastors practiced it unashamedly. Twain remembered one Methodist minister who sold an enslaved child to a fellow minister, who then profited by later selling the child downriver. As the steamboat departed with her offspring, the child’s mother wept inconsolably at the dock.42 As he got older and developed into an avid student of history, Twain came to believe that the Church had endorsed slavery for centuries and reformed its position only after congregants turned against it. Church complicity on slavery came to illustrate for him how social institutions could collude in a “lie of silent assertion . . . that nothing is going on which fair and intelligent men are aware of and are engaged by their duty to try to stop.”43

When it came to slavery, the forces of repression were especially virulent in northern Missouri, settled mostly by people from slave states. Even though Missouri lay at the intersection of the free states of Illinois and Iowa and the mixed Kansas Territory, it had a heavily enslaved population in counties strung along the Mississippi River. In fact, the proximity of free Illinois right across the waterway only heightened the dread in Hannibal that dastardly abolitionists would sneak across and spirit slaves away. “In that day,” Twain wrote, “for a man to speak out openly and proclaim himself an enemy of negro slavery was simply to proclaim

himself a madman. For he was blaspheming against the holiest thing known to a Missourian, and could not be in his right mind.”44

As much as he had warmed to the lowly Tom Blankenship, Sam Clemens gravitated to the company of the enslaved, and for someone attracted to pariahs, the human chattel were the ultimate outcasts of society. For many years, his brain stuffed with early stereotypes, he would refer to Blacks in derogatory language—after all, he grew up in a town that still had slave auctions and minstrel shows with racist impersonations of Banjo and Bones—yet his boyish affection for Black people was also unmistakable. By some instinct he reveled in their company. Of having Black children as playmates, he contended that he preferred “their society to that of the elect, I being a person of low- down tastes from the start, notwithstanding my high birth.”45

Sam spent two or three months of every summer at his uncle John Quarles’s homestead, set on the crest of a beautiful hill, four miles outside of Florida. Populated by eight Quarles children and about a dozen enslaved people, it represented an emotional haven for the boy and would reappear as the Phelpses’ farm in Huck Finn. “It was a heavenly place for a boy,” Mark Twain recalled, “that farm of my uncle John’s.”46 The meals served were hearty and irresistible—“the corn bread, the hot biscuits and wheatbread, and the fried chicken”—never to be surpassed in northern years.47 Nor was it a small thing that, in contrast to his father’s severity, John Quarles showed a winning geniality.

The plantation’s foremost appeal lay in the smokehouse and a cluster of small log cabins that made up the “negro quarter,” a place redolent with an atmosphere of magic, mystery, and folklore. Here the future novelist found figures of inexhaustible fascination, including “Aunt” Hannah, “a bedridden white-headed slave woman whom we visited daily, and looked upon with awe, for we believed she was upwards of a thousand years old and had talked with Moses.”48 It was thought “she had lost her health in the desert, coming out of Egypt. The bald spot on her head was caused by fright at seeing Pharaoh drowned.”49 The language, folkways, songs, and religion of the enslaved left lasting traces on Sam Clemens’s

imagination. He absorbed their dialects into his bloodstream and they became a part of him. Often the older Black children would chaperone younger whites, but, stepping outside their roles, they could also act as companions and co- conspirators. These unions, however pleasant, were illusory in nature. “We were comrades, and yet not comrades”; Twain remembered, “color and condition interposed a subtle line which both parties were conscious of, and which rendered complete fusion impossible.”50

The high point each summer came at night by the kitchen fi re, when the enslaved Old Uncle Dan’l would deliver a ghost story called the “Golden Arm” amid a fl ickering blaze. From Mark Twain’s luminous memories of these performances, it grows clear that he encountered in the elderly Black man his fi rst platform virtuoso, expert in tone and pacing. “We would huddle close about the old man, & begin to shudder with the fi rst familiar words; & under the spell of his impressive delivery we always fell a prey to that climax at the end when the rigid black shape in the twilight sprang at us with a shout.”51 In his many years on the lecture circuit, Mark Twain would constantly reprise the Golden Arm story along with many tricks of delivery he had learned at the feet of his fi rst mentor.

With his kindness, warmth, and intelligence, Uncle Dan’l would serve as inspiration for many characters in Mark Twain’s fiction. As he admitted, “I . . . staged him in books under his own name and as ‘Jim,’ and carted him all around—to Hannibal, down the Mississippi on a raft, and even across the Desert of Sahara in a balloon—and he has endured it all with the patience and friendliness and loyalty which were his birthright.”52 Due to prolonged exposure to slavery at the Quarleses’ farm, Twain had a fondness for Black people that didn’t stem from polite tolerance or enforced familiarity. It was deep and personal, and he was never afraid to say so, distinguishing him from many white people of his era. “It was on the farm that I got my strong liking for [Uncle Dan’l’s] race and my appreciation of certain of its fi ne qualities. This feeling and this estimate have stood the test of sixty years and more and have suffered no impairment. The black face is as welcome to me now as it was then.”53

Sometimes it can be hard to reconcile Twain’s varied memories of

slavery in Hannibal, which he once termed “the mild domestic slavery, not the brutal plantation article. Cruelties were very rare, and exceedingly and wholesomely unpopular.”54 Of course, “mild domestic slavery,” if such ever existed, was still slavery. Yet it was Twain himself who told the story of the lump of iron flung at a Black man that killed him and how his own parents had been corrupted by this system into cruel and unnatural behavior.

The situation that implicated the entire community in the crime of chattel slavery was the problem of runaway slaves. No white person who came into contact with a fugitive was spared responsibility. “To help steal a horse or a cow was a low crime,” Mark Twain said, “but to help a hunted slave, or feed him or shelter him, or hide him, or comfort him, in his troubles, his terrors, his despair, or hesitate to promptly betray him to the slave- catcher . . . was a much baser crime, & carried with it a stain, a moral smirch which nothing could wipe away.”55 While Twain understood why slave owners pursued runaways in such ferocious fashion, he was always puzzled that “the loafers[,] the tag-rag & bobtail of the community” took up the hunt with equal zeal. “It shows that that strange thing, the conscience . . . can be trained to approve any wild thing you want it to approve if you begin its education early & stick to it.”56