The South Side Weekly is an independent non-profit newspaper by and for the South Side of Chicago. We provide high-quality, critical arts and public interest coverage, and equip and develop journalists, artists, photographers, and mediamakers of all backgrounds.

Volume 12, Issue 20

Interim

Editor-in-Chief Adam Przybyl

Investigations Editor Jim Daley

Immigration Project

Editor Alma Campos

Senior Editors Martha Bayne

Christopher Good Olivia Stovicek

Jocelyn Martinez-Rosales

Community Builder Chima Ikoro

Editor Emeritus Jacqueline Serrato

Public Meetings Editor Scott Pemberton

Art Director Shane Tolentino

Director of Fact Checking: Ellie Gilbert-Bair

Fact Checkers: Jim Daley

Christopher Good Kateleen Quiles

Susie Xu

Layout Editor Tony Zralka

Publisher Malik Jackson

Office Manager Mary Leonard

Advertising Manager Susan Malone

The Weekly publishes online weekly and in print every other Thursday. We seek contributions from all over the city.

Send submissions, story ideas, comments, or questions to editor@southsideweekly.com or mail to:

South Side Weekly

6100 S. Blackstone Ave. Chicago, IL 60637

For advertising inquiries, please contact: Susan Malone (773) 358-3129 or email: malone@southsideweekly.com

For general inquiries, please call: (773) 643-8533

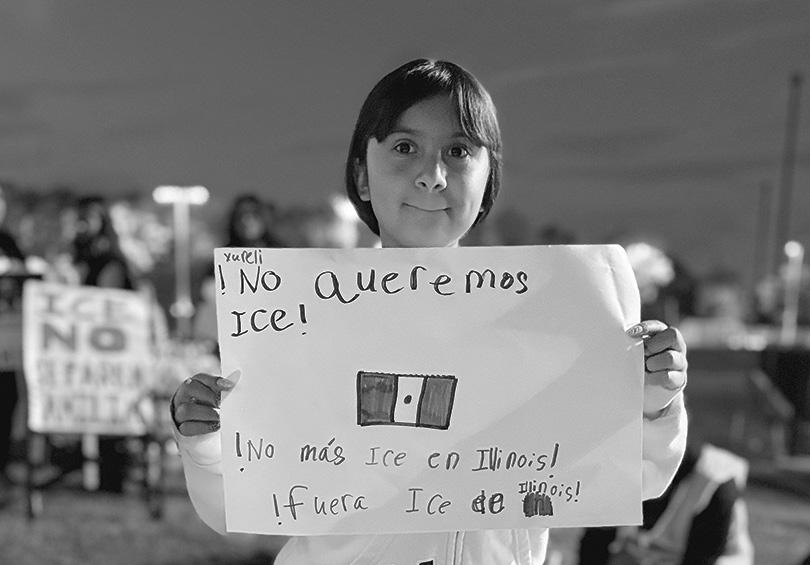

Last Tuesday, October 14, a large-scale federal immigration operation swept through Chicago’s East Side neighborhood, bringing armed agents, helicopters, and tear gas into a neighborhood of families and workers, and leaving schools and small businesses reeling in its aftermath. In recent months, similar raids have unfolded in other South and West Side neighborhoods, terrifying families.

On the East Side, car horns blared through the streets—a warning system residents used to alert one another to danger. Inside a nearby high school, students were mid-test when the building went into lockdown. Helicopters circled overhead, federal agents’ vehicles carelessly sped through intersections, and agents deployed tear gas at residents despite the presence of elders, children and even babies.

One mother said her seventeen-year-old daughter described it this way:

“It felt like we were in the middle of a war.”

The mother said she was at work when the social media alerts started. Her high schooler started texting her that ICE was in the neighborhood, that kids were crying, that they could hear sirens and see helicopters.

“How do I go save my children from something like that when I’m an immigrant myself?” she said.

A community organizer described how she rushed to the scene on 105th and Avenue N. “Several of us were there as rapid-response people. And that’s when ICE was just abruptly throwing the tear gas at us.”

By midmorning, the agents were already forcing entry into small businesses on Commercial Avenue in South Chicago. “They were provoking,” she said. “People say it’s the activists, but no, ICE was intentionally provoking.”

She saw officers strike residents. At one point, she said, “They grabbed two U.S. citizens. One of them was a minor. I was trying to tell them, ‘Please release him, he’s a minor,’ and then they started tear-gassing us again. They’re violating every safety rule,” she said. “They almost ran over a woman who was just walking on the sidewalk.”

The violence that unfolded that morning was carried out with intention— authorized by federal leadership. No government should arm agents with tear gas and send them into neighborhoods of families and children. Yet that’s exactly what happened, and it continues to happen every day across Chicagoland.

In recent days, courts have tried to respond. A Cook County judge barred ICE from making civil arrests at courthouses, while another ordered agents to wear and activate body cameras. Cook County President Toni Preckwinkle has proposed “ICE-free zones” in schools, parks, and libraries. But those measures mean little to the families who’ve already lived through raids.

What happened on the East Side, and in neighborhoods across Chicago, demands accountability and memory. The images, the testimonies, and the fear that families describe are not fleeting moments of chaos. They are evidence of how state power enforces borders through violence, turning immigration enforcement itself into a weapon against communities. If there’s to be any justice, there must be accountability, not just policies written after the fact, but consequences for the agencies that terrorize communities.

We urge our readers to keep sharing information about the presence of federal agents with rapid responders, community organizations, and the press. The more we document, the harder it becomes for power to hide what it has done.

a tragic homecoming

After nearly two decades in Chicago, Silverio Villegas González returned to Michoacán in a coffin. alma campos ............................................ 4

un trágico regreso a casa

Tras casi dos décadas en Chicago, Silverio Villegas González regresó a Michoacán en un ataúd. alma campos, traducido por gisela orozco 6

the aftermath

An empty apartment. A solitary protester. A budding community: What remains after ICE abductions?

jim daley .................................................. 9

thousands march against trump

Spurred by ICE agents’ recent brutality in Chicagoland, more than 200,000 flooded the Loop Saturday to protest..

jim daley ................................................ 12

doing it her way

Sandra Jackson-Opoku had to wade through ageism, genre biases, and cozy mystery industry expectations to get where she is today.

tina jenkins bell .................................. 14

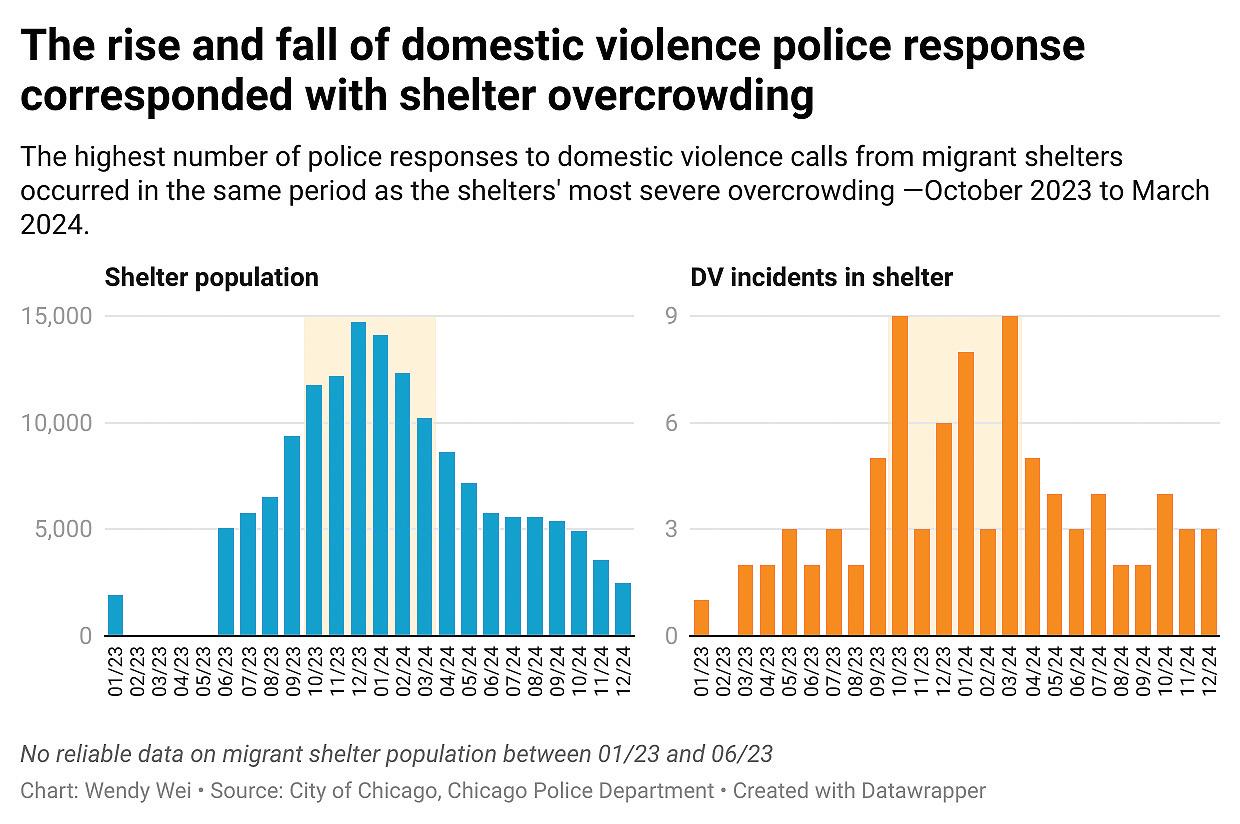

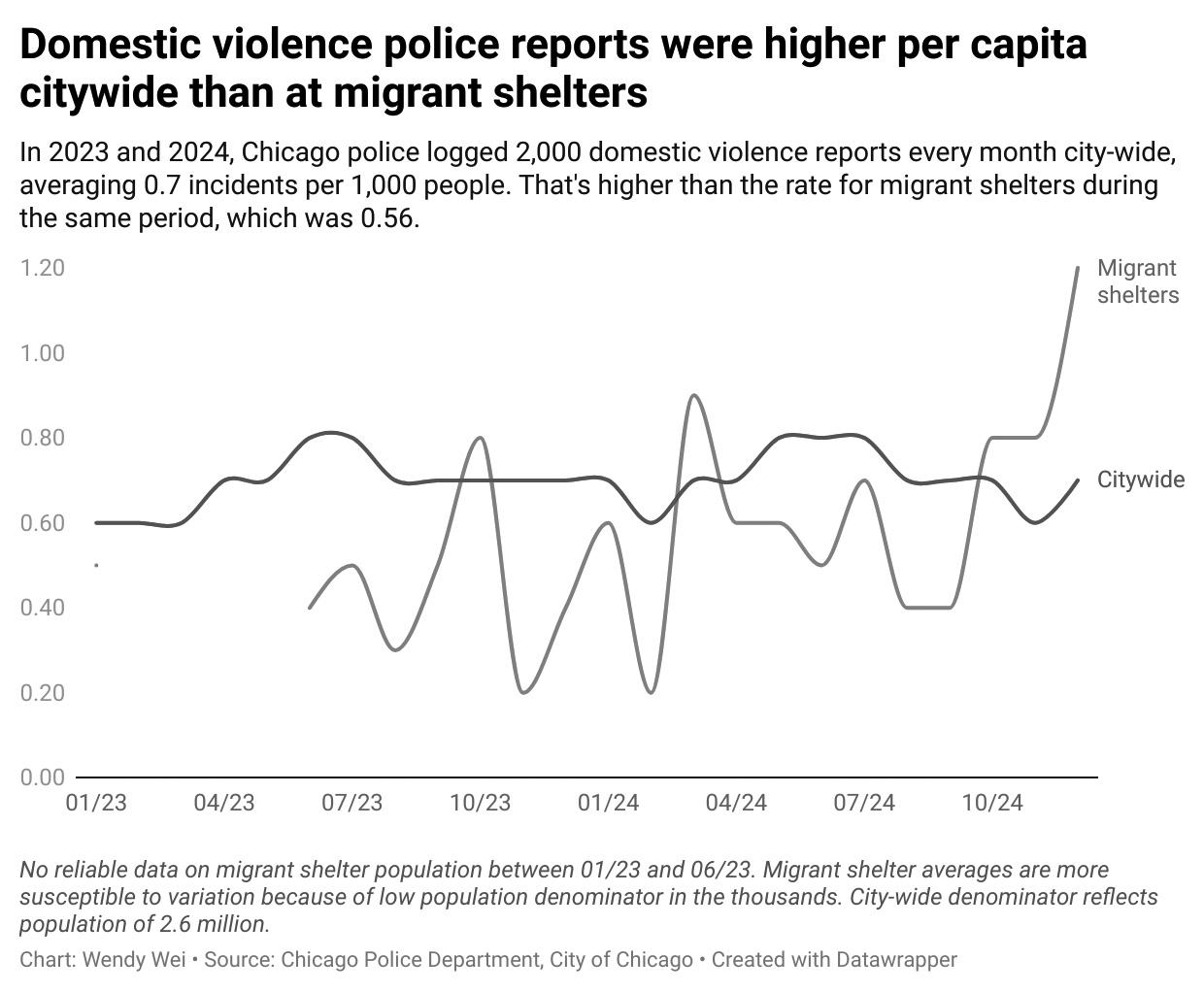

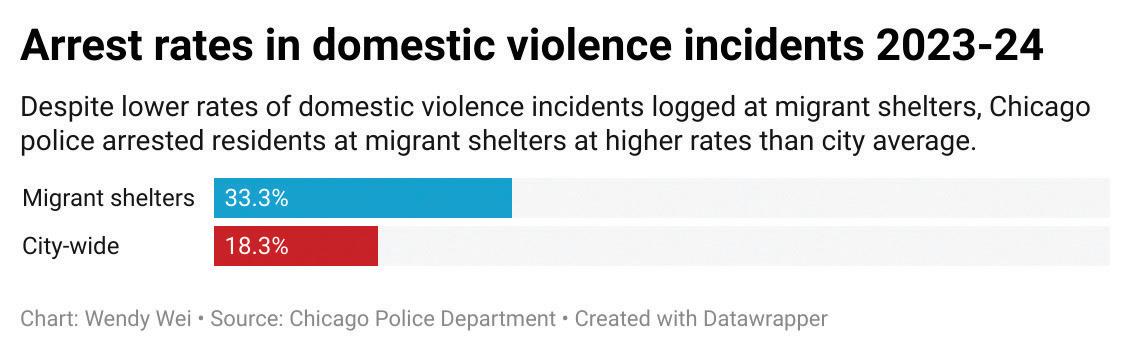

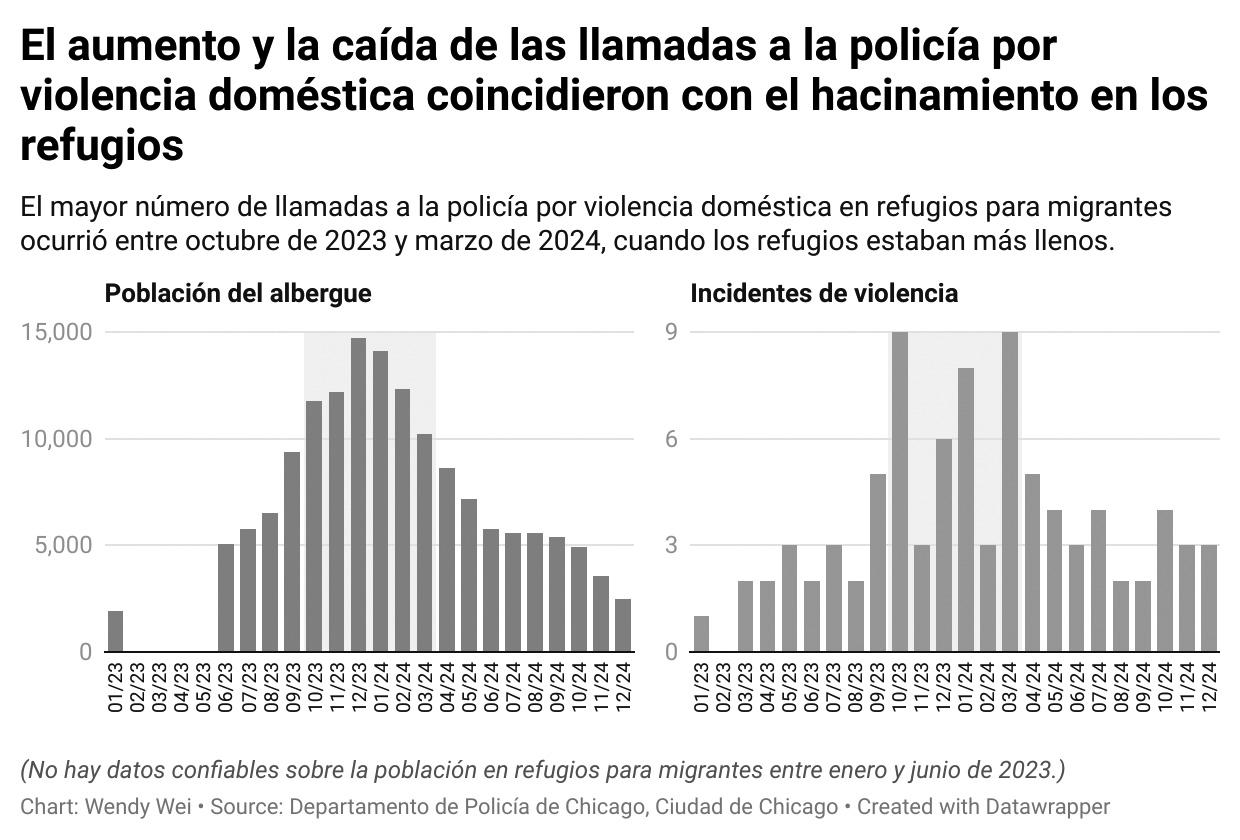

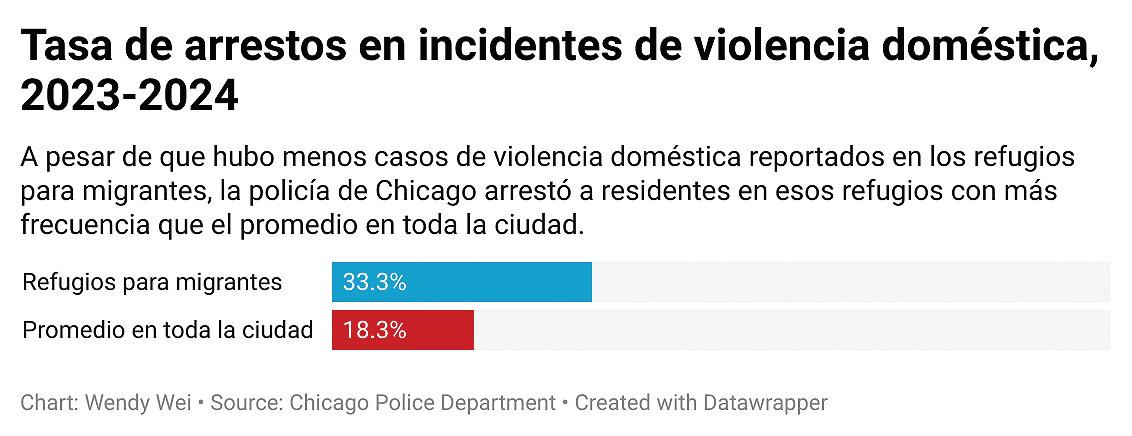

seeking shelter

Despite having fewer reported incidents than the city average, migrant shelters saw more domestic violence arrests during the two years they operated. wendy wei 16

buscando refugio

En los refugios para inmigrantes de Chicago se registró menos violencia doméstica que en el promedio de la ciudad, pero un mayor número de arrestos. wendy wei, traducido por leslie hurtado ........... 20

public meetings report

A recap of select open meetings at the local, county, and state level.

scott pemberton and documenters 23

Cover illustration by Gaby FeBland

After nearly two decades in Chicago, Silverio Villegas González returned to Michoacán in a coffin. His death at the hands of federal agents left two families divided by borders, shattered with grief, and with a lot of unanswered questions.

BY ALMA CAMPOS

He came back in a box. A wooden coffin wrapped in cardboard, the kind used to protect freight. Eighteen years after leaving, that was how Silverio Villegas González returned to Michoacán. The plane landed in Guadalajara; from there, the hearse drove ten hours through the hills until it reached Loma de Chupio, a rural community just outside the town center around 4:00pm on Thursday, September 26.

According to Michoacán-based reporter César Cabrera, who attended the funeral, the family held the wake inside the small wooden home where Villegas grew up—four rooms, a tin roof. About twenty people came the first night: brothers, nephews, neighbors. Behind Villegas González’s casket, large flower arrangements leaned against the wall—one filled with red and white roses, another with yellow lilies, white blooms, and green foliage. A gold-colored crucifix stood to the left of the coffin, reflecting the candlelight. The next day, the church in Irimbo was full.

municipality paid for the burial.

Federal immigration agents fatally shot Villegas González during a traffic stop in Franklin Park on the morning of September 12. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) later claimed one agent was “seriously injured” after being dragged by Villegas González’s car as he tried to flee. Body-camera footage obtained by the Weekly shows one agent telling a Franklin Park police officer his injury was “nothing major,” however. Neither federal agent was wearing a body-camera at the time of the shooting.

The Mexican Consulate in Chicago paid for the flight. The state covered the transport from Guadalajara. The

Cabrera said Villegas González’ return to Michoacán was one among many. Each year, hundreds of bodies are flown back to Michoacán from U.S. cities like Chicago, Los Angeles, and Houston. In 2025, at least fifty-eight remains of Michoacanos who died in the United States have been repatriated to the state. Some cases draw public attention, he said, but many others remain private at the families’ request.

In July, another man from Zinapécuaro—Jaime Alanís García, the first Michoacano to die during an ICE raid that year—fell from a greenhouse roof in California while trying to escape agents. His family, Cabrera said, was “very, very poor.”

The Consulate General of Mexico office in Chicago that serves Illinois and northern Indiana, and handled roughly 700 repatriations last year. Most involved deaths from illness, accidents, or natural causes.

“Sometimes relatives reach out to us, and sometimes we’re notified by local authorities or medical examiner’s offices,” said Saúl Juárez Montaño, Consul for Protection and Legal Affairs. Once contact is made, he explained, consular staff interview the family and conduct what they call a socioeconomic assessment to determine whether they qualify for financial assistance.

“In many cases, when people are undocumented and a family member dies in a way that involves the police or an

investigation, they’re afraid to contact the authorities and try to get an answer of what happened,” said Javier Cerritos De Los Santos, also a Consul for Protection and Legal Affairs.

“When a case involves an officer of the law, the Mexican Consulate, as it has done in the past, would request a full investigation of what really happened, so the family can be totally sure what happened. And if there’s anything else that should be done regarding this type of situation,” he said.

The consulate also maintains “a list of funeral homes that we’ve worked with throughout the years—ones that know how to do this process correctly,” Cerritos De Los Santos said. Those funeral homes handle the embalming, the apostille of the death certificate, and the certification required for a body to cross the border. Once everything is in order, the consulate issues “the visa for the remains so that the body can enter Mexico.”

Juárez Montaño said the office works as quickly as possible once documentation is complete. “Families in Mexico are used to, if somebody dies, you’re already at night at the funeral. We say, ‘velando al difunto esa misma noche,’ right? And the next day, we’re already taking them to the cemetery and burying them. That’s the Mexican tradition,” he said.

“But when that happens here, we have to explain to the family that here, especially a family in Mexico, that in the U.S. it’s totally different. The body could take a week or two in the morgue, then the funeral home has to pick up the body, get the certificate, then get the other documentation that they have to bring to us, and obviously we have to issue the visa for the body to travel to Mexico.”

When Villegas González’ coffin arrived in Loma de Chupio, his mother, who was waiting for its arrival, was inconsolable, Cabrera said. Two of his brothers coordinated the wake inside the family’s small wooden home.

Villegas González’ brother Jorge Villegas González described him as the kind of man who avoided confrontation. “My brother was a calm person, quiet,” he said. “He was very loving with his children, he was everything to them.”

Jorge added that the family was devastated because of how Villegas González was killed. The family is calling on both the Mexican and U.S. governments for answers. They plan to take legal action against the U.S. government once the mourning period passes. “We want help so this can be clarified,” Jorge said. “If the officer was trained to kill unarmed people, that cannot be called justice.”

The town of Irimbo “is small, a place with a high level of poverty,” Cabrera said. According to 2022 data from INEGI, Mexico’s national statistics agency, about half of its residents live in poverty and nearly twelve percent in extreme poverty.

“Silverio’s house is made of wooden poles,” Cabrera said. “The roof is tin. It’s four rooms at most; four by four, and they have a little cornfield, but unfortunately that’s not enough to get by.”

He described the region as one where migration has become a kind of routine. “It’s

pushes them,” he said. “It’s the last resort they have.”

After Villegas González’ death, his girlfriend of nearly two years, Blanca Mora, couldn’t bring herself to return to work. She’d been cleaning houses and offices, but her employer noticed how shaken she was and told her to take time off. Then, he replaced her.

In her first interview since Villegas González’ death, Mora told the Weekly that she spent three days in the hospital being treated for symptoms related to stress, panic, and anxiety brought on by trauma and grief.

“The doctors told me, ‘Right now you’re going to be like a baby. You have to learn to crawl and come back,’” she said.

in a friend’s garage, and moved into a small room in Berwyn.

“We stayed in communication with her and her family,” Torres said. “They even came to an event we held one month after Silverio’s death to honor his life and demand safer communities.”

That event took place at Gouin Park in Franklin Park, where local residents gathered to remember Villegas González and denounce what Torres called “an unnecessary and cruel killing.” For PASO, she said, the work goes beyond offering aid after a tragedy—it’s about making sure communities know their rights when ICE comes. “We continue to say it clearly,” Torres said. “ICE is not welcome in our neighborhoods. They create insecurity, not safety.”

a natural phenomenon because of poverty, because of violence,” he said. “That’s why so many people leave.”

Cabrera noted that even after eighteen years in the United States, Silverio’s family’s financial situation had not changed. “Just because you go there doesn’t mean things will go well overnight,” he said. “People there have families too—they have expenses—and the conditions under which they’re hired have a lot to do with it.”

In Michoacán, Cabrera has covered many cases like Silverio’s—migrants who leave searching for stability and return years later in wooden boxes. “It’s necessity that

Without steady income, rent became impossible to cover, she said. A local group, PASO West Suburban Action Project gave her a $500 check that helped her stay afloat for another month.

“As soon as we got word that there was ICE activity in Franklin Park, we mobilized immediately,” said Ana Torres, an organizer and communications lead with PASO.

The apartment in Franklin Park no longer felt livable, according to Mora. Her thirteen-year-old daughter couldn’t sleep there because the home reminded her of what had happened to Villegas. “It affected her to be there,” Mora said. So they packed their things, most of which are now stored

Villegas González and Mora lived together in Franklin Park for about eight months before the killing. They were looking forward to celebrating their two-year anniversary together on October 10.

Most mornings were the same: he’d wake her before work with “levántate, chiquita” (“get up, little one”). He’d help get the kids dressed, make sure everyone ate something— yogurt, a piece of fruit, a glass of milk.

“He was always attentive,” Mora said. When she had a migraine, he’d tell her to rest and would take the children from school. Villegas González’ two sons, ages three and seven, lived with them, along with Mora’s daughter. They called her mamá de arroz—rice mom—a nickname that started as a joke and stuck.

Most days, they talked about finding a bigger apartment, maybe renting a house when her daughter finished middle school.

The morning of September 12, Mora hurried to get ready. She was running late, worried about traffic. Villegas González stopped her at the door, asking for a moment, to give him a hug. His daughter joined in and kissed him on the forehead.

After dropping off her daughter at school, Mora returned home to change for work. Around that time, Villegas González usually called after leaving his children at school and heading to his job, a small check-in they shared every morning. When the call didn’t come, she began to worry. She called his boss, who said he hadn’t

shown up for work. She called his sister and the woman who watched the kids. No one had heard from him.

Then she opened Facebook.

“I went on Facebook and saw the video,” Mora said. “I said, okay, it was an accident, a crash… but he’s fine, from what it looks like.”

She kept watching.

“Then I saw they were hitting him,” she said. “You can hear them yelling at him, and I thought, they’re going to take him to the hospital, they’re going to take care of him.”

A few minutes later she refreshed her page. “That’s when I saw they announced he’d died,” she said.

“I couldn’t believe it. I thought, maybe it’s a mistake, maybe they confused him with someone else. I was just asking God that they’d made a mistake.”

Because the couple wasn’t married, Mora wasn’t part of the repatriation of Villegas González’ body. After federal agents killed him, his family in Mexico

became the official points of contact with the Mexican Consulate, which requires next-of-kin authorization for repatriation.

Mora had lived with Villegas González, raised children alongside him, and shared a life, yet she was treated as an outsider.

“They didn’t take me into account at all, because I wasn’t his wife,” she said. “I wanted them to let me say goodbye to him the way I should have,” Blanca said. “He was my partner.” ¬

Alma Campos is the Weekly’s immigration reporter and project editor.

Tras casi dos décadas en Chicago, Silverio Villegas González regresó a Michoacán en un ataúd. Su muerte a manos de agentes federales dejó a dos familias divididas por las fronteras, destruidas por el dolor y con muchas preguntas sin respuesta.

Regresó en una caja. En un ataúd de madera envuelto en cartón, de los que se usan para proteger la mercancía. Dieciocho años después de su partida, así fue como Silverio Villegas González regresó a su estado natal, Michoacán. El avión aterrizó en el aeropuerto de Guadalajara, capital del estado de Jalisco; desde allí, la carroza fúnebre recorrió diez horas por las colinas hasta llegar a Loma de Chupio, rancho del municipio de Irimbo, a eso de las 4:00 p. m. del jueves 26 de septiembre.

Según el reportero michoacano César Cabrera, quien asistió al funeral, la familia realizó el velorio en la pequeña casa de madera donde creció Villegas, de cuatro habitaciones y con techo de lámina. Unas veinte personas acudieron la primera noche: hermanos, sobrinos, vecinos.

Detrás del ataúd de Villegas González, estaban reclinados contra la pared grandes arreglos florales: uno lleno de rosas rojas y blancas, otro con lirios amarillos, flores blancas y follaje verde. Un crucifijo dorado se alzaba a la izquierda del ataúd, reflejando la luz de las velas. Al día siguiente, la iglesia de Irimbo estaba llena de feligreses que se dieron cita para la misa de cuerpo presente.

La mañana del 12 de septiembre, agentes federales de inmigración le dispararon mortalmente a Villegas

González durante una detención por tráfico en el suburbio de Franklin Park. El Departamento de Seguridad Nacional (DHS) afirmó posteriormente que un agente resultó “gravemente herido” tras ser arrastrado por el auto de Villegas González mientras éste intentaba huir. Sin embargo, las imágenes de la cámara corporal obtenidas por el Weekly muestran a un agente diciéndole a un policía de Franklin Park que sus heridas “no eran graves”. Al momento del tiroteo, ninguno de los agentes federales portaba una cámara corporal.

El Consulado General de México en Chicago pagó el vuelo. El estado cubrió el transporte desde Guadalajara. El municipio pagó el entierro. Cabrera afirmó que el regreso de Villegas González a Michoacán fue uno de muchos. Cada año, cientos de cuerpos regresan a Michoacán desde ciudades estadounidenses como Chicago, Los Ángeles y Houston. En 2025, al menos veintiocho restos de michoacanos que murieron en Estados Unidos fueron repatriados al estado. Algunos casos atraen la atención pública, afirmó, pero muchos otros permanecen en privado a petición de las familias.

En julio, otro hombre de Zinapécuaro —Jaime Alanís García, el primer michoacano en morir este año durante

una redada del Servicio de Inmigración y Control de Aduanas (ICE)— se cayó del techo de un invernadero en California mientras intentaba escapar de los agentes. Su familia, dijo Cabrera, era “muy, muy pobre”.

El año pasado, la oficina del Consulado General de México en Chicago, que atiende a Illinois y el norte de Indiana, gestionó aproximadamente 700 repatriaciones. La mayoría se debió a fallecimientos por enfermedad, accidentes o causas naturales.

“A veces, los familiares nos contactan y, en otras ocasiones, las autoridades locales o las oficinas del médico forense nos dejan saber”, dijo Saúl Juárez Montaño, Cónsul de Protección y Asuntos Jurídicos. Una vez establecido el contacto, según explicó, el personal consular entrevista a la familia y realiza lo que ellos llaman una evaluación socioeconómica para determinar si califican para recibir asistencia financiera.

“En muchos casos, cuando las personas son indocumentadas mueren y un familiar muere de una manera que implica a la policía o una investigación, temen contactar a las autoridades e intentar obtener una respuesta sobre lo sucedido”, dijo Javier Cerritos De Los Santos, también Cónsul de Protección y Asuntos Jurídicos.

“Cuando un caso involucra a un

agente de la ley, el Consulado de México, como lo ha hecho en el pasado, solicitaría una investigación completa de lo sucedido para que la familia tenga plena certeza de lo ocurrido. Y si hay algo más que deba hacerse con respecto a este tipo de situación”, explicó.

El consulado también mantiene “una lista de funerarias con las que hemos trabajado a lo largo de los años, las que saben cómo realizar este proceso correctamente”, destacó Cerritos De Los Santos. Estas funerarias se encargan del embalsamamiento, de la apostilla del certificado de defunción y de la certificación necesaria para que un cuerpo cruce la frontera. Una vez que todo está en orden, el consulado emite “la visa para los restos, para que el cuerpo pueda ingresar a México”.

Juárez Montaño destacó que la oficina trabaja lo más rápido posible una vez que se completa la documentación. “Las familias en México están acostumbradas a que, si alguien fallece, ya estén en el funeral esa misma noche. Decimos: ‘velando al difunto esa misma noche’, ¿no? Y al día siguiente, ya los llevamos al cementerio y los enterramos. Esa es la tradición mexicana”, explicó.

“Pero cuando eso sucede aquí, tenemos que explicarles a las familias que, especialmente en México, en Estados

Unidos es totalmente diferente. El cuerpo puede tardar una o dos semanas en la morgue, luego la funeraria tiene que recogerlo, obtener el certificado, obtener la documentación que nos deben entregar y, obviamente, emitir la visa para que el cuerpo viaje a México”.

Cuando el ataúd de Villegas González llegó a Loma de Chupio, su madre, que lo esperaba, estaba desconsolada, contó Cabrera. Dos de sus hermanos coordinaron el velorio en la pequeña casa de madera de la familia.

El hermano de Villegas González, Jorge Villegas González, lo describió como un hombre que evitaba la confrontación. “Mi hermano era una persona tranquila, callada”, dijo. "Era muy cariñoso con sus hijos; era todo para ellos”.

Jorge agregó que la familia estaba devastada por la muerte de Villegas González. La familia exige respuestas tanto a los gobiernos de México como al de Estados Unidos. Planean emprender acciones legales contra el gobierno estadounidense una vez que pase el período de duelo. “Queremos ayuda para que esto se aclare”, señaló Jorge. “Si el agente estaba entrenado para matar a personas desarmadas, a eso no se le puede llamar justicia”.

El pueblo de Irimbo "es pequeño, un

lugar con un alto nivel de pobreza", señaló Cabrera. Según datos de 2022 del Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía de México (INEGI), aproximadamente la mitad de sus habitantes vive en pobreza y casi el 12% en pobreza extrema.

“La casa de Silverio está hecha de postes de madera”, señaló Cabrera. “El techo es de lámina. Tiene cuatro habitaciones como máximo; cuatro por cuatro, y tiene un pequeño campo de maíz, pero lamentablemente no les alcanza para sobrevivir”.

Describió la región como una donde la migración se ha convertido en una especie de rutina. “Es un fenómeno natural debido a la pobreza y a la violencia”, dijo. “Por eso tanta gente se va”.

Cabrera señaló que incluso después de dieciocho años en Estados Unidos, la situación financiera de la familia de Silverio no había cambiado. “El hecho de que vayas allí no significa que las cosas vayan a ir bien de la noche a la mañana”, destacó. “Allá la gente también tiene familia, tiene gastos, y las condiciones en las que los contratan influyen mucho”. En Michoacán, Cabrera ha cubierto muchos casos como el de Silverio: migrantes que se van en busca de estabilidad y regresan años después en cajas de madera. “Es la necesidad lo que los impulsa”, agregó. “Es el último recurso

que les queda”.

Tras la muerte de Villegas González, su novia de casi dos años, Blanca Mora, no se atrevía a volver al trabajo. Había estado limpiando casas y oficinas, pero su jefe notó lo afectada que estaba y le pidió que se tomara un tiempo libre. Luego, la reemplazó.

En su primera entrevista desde la muerte de Villegas González, Mora contó al Weekly que pasó tres días en el hospital recibiendo tratamiento por síntomas relacionados con el estrés, el pánico y la ansiedad provocados por el trauma y el duelo.

“Los médicos me dijeron: ‘Ahora mismo vas a estar como un bebé’. Tienes que aprender a gatear y a recuperarte’”, relató.

Sin ingresos estables, el alquiler se volvió imposible de cubrir, comentó. Un grupo local, PASO West Suburban Action Project, le dio un cheque de $500 que la ayudó a mantenerse a flote un mes más.

“En cuanto nos enteramos de que había actividad de ICE en Franklin Park, nos movilizamos de inmediato”, dijo Ana Torres, organizadora y responsable de comunicaciones de PASO.

El apartamento en Franklin Park ya no parecía habitable, según Mora. Su hija de trece años no podía dormir allí porque la casa le recordaba lo que le había sucedido a Villegas. “Le afectó estar allí”, destacó Mora. Así que empacaron sus cosas, la mayoría de las cuales ahora están guardadas en el garaje de una amiga, y se mudaron a una pequeña habitación en Berwyn.

“Nos mantuvimos en contacto con ella y su familia”, dijo Torres. “Incluso asistieron a un evento que organizamos un mes después de la muerte de Silverio para honrar su vida y exigir comunidades más seguras”.

Ese evento tuvo lugar en el Gouin Park en Franklin Park, donde los residentes locales se reunieron para recordar a Villegas González y denunciar lo que Torres llamó “un asesinato innecesario y cruel”. Para PASO, dijo, el trabajo va más allá de ofrecer ayuda después de una tragedia; se trata de asegurar que las comunidades conozcan sus derechos cuando llega ICE. “Seguimos diciéndolo

claramente”, destacó Torres. “ICE no es bienvenido en nuestros vecindarios. Crean inseguridad, no seguridad”.

Villegas González y Mora vivieron juntos en Franklin Park durante unos ocho meses antes del asesinato. Estaban deseando celebrar su segundo aniversario juntos el 10 de octubre.

Casi todas las mañanas eran iguales: él la despertaba antes del trabajo con un “levántate, chiquita”. Ayudaba a vestir a los

niños, se aseguraba de que todos comieran algo: yogur, una pieza de fruta, un vaso con leche.

“Siempre era muy atento”, recordó Mora. Cuando ella tenía migraña, él le decía que descansara y llevaba a los niños de la escuela. Los dos hijos de Villegas González, de tres y siete años de edad, vivían con ellos, junto con la hija de Mora. La llamaban “mamá de arroz”, un apodo que empezó como una broma y que se le quedó.

Casi todos los días hablaban de

buscar un apartamento más grande, tal vez alquilar una casa cuando su hija terminara la escuela intermedia.

La mañana del 12 de septiembre, Mora se apresuró a prepararse. Iba tarde, preocupada por el tráfico. Villegas González la detuvo en la puerta, pidiéndole un momento para abrazarlo. Su hija se unió a ellos y lo besó en la frente.

Después de dejar a su hija en la escuela, Mora regresó a casa para cambiarse e ir a trabajar. En ese entonces, Villegas González solía llamar después de dejar a sus hijos en la escuela y dirigirse a su trabajo, una breve charla que compartían cada mañana. Al no recibir la llamada, empezó a preocuparse.

Llamó a su jefe, quien le dijo que no se había presentado a trabajar. Llamó a su hermana y a la mujer que cuidaba a los niños. Nadie sabía nada de él.

Entonces abrió Facebook.

“Entré en Facebook y vi el video”, narró Mora. “Dije: ‘Bueno, fue un accidente, un choque… pero está bien, por lo que parece’”.

Siguió mirando.

“Entonces vi que lo estaban golpeando”, dijo. “Se les oye gritarle y pensé: ‘Lo van a llevar al hospital, lo van a cuidar’”. Unos minutos después, actualizó su página. “Fue entonces cuando vi que anunciaron su muerte”, contó. “No podía creerlo. Pensé: ‘Quizás fue un error, quizás lo confundieron con otra persona’. Sólo le pedía a Dios que se hubieran equivocado”.

Como la pareja no estaba casada, Mora no participó en la repatriación del cuerpo de Villegas González. Tras su muerte a manos de agentes federales, su familia en México se convirtió en el punto de contacto oficial con el Consulado Mexicano, que, para la repatriación, requiere la autorización del pariente más cercano.

Mora había vivido con Villegas González, criado a sus hijos junto a él y compartido una vida, pero la trataron como a una extraña.

“No me tomaron en cuenta para nada, porque no era su esposa”, dijo. “Quería que me dejaran despedirme de él como debía”, señaló Blanca. “Era mi pareja”. ¬

Alma Campos es la reportera de inmigración y editora de proyectos del Weekly

An empty apartment. A solitary protester. A budding community: What remains after ICE abductions?

BY JIM DALEY

Welcome to our home—the

refuge after walking thousands of miles

family, cozy, all together? Perhaps this apartment was their first small bit of

agents pulled up. Visibly shaken, the couple that had

been in the SUV stood on the sidewalk, talking to a police officer. The night before, they’d been at Wrigley Field for a Cubs playoff game. Now, their morning upended, they were considering the potential risks of filing a police report about a car crash perpetrated by federal agents.

A few neighbors who’d filmed the abduction and crash stood near the couple, angry at what had just unfolded. A tow truck driver, waiting for the police to finish taking their report, collected a few shards of the taillight and stacked them gingerly on the curb. “They said they was just gonna take criminals, bad people,” he said quietly. “But they’re acting like animals.”

After the police left, the neighbors who stuck around spoke to reporters, eager to share their videos and denounce the agents’ behavior. After an hour or two, they parted ways, called by the demands of work and daily life. Aside from the detritus of the crash, nothing indicated the terror and chaos that had briefly gripped the site that morning.

Hours later as the sun began to set, a lone woman stood on the corner, holding a tall black candle. Her face was obscured by the hood of a knee-length forest green cloak. Three more candles sat on the curb before her, a few feet from where the SUV had been that morning.

Alone and anonymous, she kept a vigil in the gathering darkness. “I’m here for Debbie,” she said.

Autumn’s early dusk had fallen on the Rogers Park church, and a warm glow emanated from within. A sign on the church wall advertising the daily Mass schedule was covered with a black cloth because earlier that day, October 12, immigration agents had been spotted nearby. After that morning’s Mass concluded, parishioners, warned of the threat, had been reluctant to leave the church, and neighbors had volunteered to escort them to their cars.

During the day, word of the sighting had spread through networks on social media and cell-phone threads. Now, a yard sign detailing one’s legal rights when talking to agents was prominently displayed at the end of the block. On the sidewalk, someone had chalked instructions for reporting sightings of agents to the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights (ICIRR), and had written “We keep us safe.”

Inside the church, the few people in attendance approached the altar to receive Holy Communion. When Mass concluded, they slipped out the door one by one. Later that week, the church’s pastor would be heading to Rome, possibly to have an audience with the Pope. Would he tell the Chicagoborn pontiff what had unfolded in his hometown that day? The priest didn’t say.

Outside, in a scene that’s been repeated in neighborhoods across Chicago in recent weeks, another kind of communion was taking shape.

Up and down the block, small groups of people stood and talked to one another. Most had never met before. Many wore whistles around their necks to warn the neighborhood in case agents were spotted. A few stayed near the church steps, watching in all directions, while others walked off to patrol the surrounding streets. In the wake of the agents’ violence, they were building community and loving their neighbors.

“It’s really heartening to know that there’s people out there that’ll catch you if you’re falling,” said a neighbor named Julie who was among those keeping watch. That morning, she’d shouted at immigration agents from her apartment window; now, she was plugged into neighborhood text-message trees and social media groups. “And we’ve got to look out for each other.” ¬

Jim Daley is the Weekly’s investigations editor.

Spurred by ICE agents’ recent brutality in Chicagoland, more than 200,000 flooded the Loop Saturday to protest.

BY JIM DALEY

Some 250,000 people attended Saturday’s “No Kings” demonstration in the Loop, one of thousands nationwide that were organized by Indivisible and marked by peaceful defiance of President Donald Trump’s efforts to consolidate authoritarian rule. The demonstrations are one of the largest single-day protests in U.S. history, and come at a time when Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents have rampaged across Chicagoland at Trump’s behest, abducting citizens and noncitizens alike and killing one person.

Mayor Brandon Johnson, Cook County Commissioner Tara Stamps and County Board President Toni Preckwinkle, Lieutenant Gov. Juliana Stratton, Gov. J.B. Pritzker, State Senator Graciela Guzmán, Congresspersons Jonathan Jackson, Jesús “Chuy” Garcia, Delia Ramirez, and Mike Quigley, Senator Dick Durbin, and several City Council members joined grassroots organizers at the Butler Field bandshell in Grant Park before the march.

“Donald Trump is using ICE as his private, militarized occupying force,” Johnson said in his address. “We are saying,

emphatically clear: We do not want troops in our city, we do not want our city to be occupied.”

Johnson noted that his enslaved ancestors partook in a general strike when, as W.E.B. DuBois observed in Black Reconstruction, they fled plantations and crossed Union Army lines during the Civil War. He called for similar direct action to resist Trump.

“I’m calling on Black people, white people, brown people, Asian people, immigrants, gay people, from around this country to stand up against tyranny, and to

send a clear message to the ultra-rich and big corporations!” Johnson shouted. The crowd roared its approval.

In neighborhoods such as Beverly, Little Village and Lincoln Park, people gathered for smaller solidarity rallies. Midwesterners also came from around the Great Lakes to participate in Saturday’s protest, one of the biggest Chicago has ever seen. Thomasine Jones, who lives in Michigan, attended with her daughter Angela Coleman, a South Sider.

“If we’re gonna save our democracy, we have to show up,” Jones said. She added

that ICE “were not requested to come here, and we want them out—not only Chicago, but all over our country.”

Coleman, a CPS teacher, agreed. “We’re all human beings, so everybody belongs here and we have a right to be here,” she said. “I cannot believe that this is happening, but I’m a teacher. We have a saying: ‘When we fight, we win.’”

In response to the nationwide protests, which Republicans have characterized as “anti-American,” the president posted an AI-generated video on social media of himself wearing a crown and flying a fighter jet over American cities while dumping feces on protesters.

After the rally, as throngs of demonstrators slowly made their way up Michigan Avenue, Congressperson Jesús “Chuy” Garcia (IL-4) stayed behind in Butler Field, chatting with constituents as Gloria Gaynor’s “I Will Survive” played over loudspeakers. Garcia told the Weekly that Trump “has it in for Chicago” because it’s a city that was built and strengthened by immigrants.

“The cruelty demonstrated by ICE,

and lawlessness, and injury that’s being caused to communities all over the city of Chicago is terrible,” he said. “That, coupled with the [federal government] shutdown and the cuts in essential programs for people are literally starving and hurting people across Chicagoland and across the country.”

Diane Ruiz, a resident of the Southwest Side who was sporting a t-shirt that read “Hot Latinas Melt ICE,” said federal raids have worsened daily life in her community.

“People are afraid to leave their homes just to do normal things, taking their kids to school, picking their kids up from school, going out to eat, to get some groceries,” she said. She added that she hopes the demonstration brings people together.

“I’d like to see us really be there for one another, like in droves, and help each other and eventually get ICE out of here,” she said. “They’re not welcome.” ¬

Jim Daley is the Weekly’s investigations editor

Two decades after finding renown as a literary novelist, Sandra Jackson-Opoku has begun a new chapter as a cozy mystery author.

BY TINA JENKINS BELL

In 2023, the year renowned literary author Sandra Jackson-Opoku turned seventy, she gave herself a piece of advice: put up or shut up.

Realizing she had more days behind her than ahead only fueled her. “I’m still productive and working, though I have less time to do it,” she said. “So there’s a constant pressure from outside, and then this internal pressure to get things done, get things out, and make my mark while I’m still here.”

In July, a little over two decades after Jackson-Opoku’s last novel was published, Minotaur Books released her first cozy mystery, Savvy Summers and the Sweet Potato Crimes, to wide acclaim. JacksonOpoku is as giddy with her new book’s success as she is proud of the hard work she put into changing her status from a formerly to currently published novelist. Moving from one stage to another wasn’t easy. She had to wade through ageism, genre biases, and industry expectations to get where she is today.

To be clear, Jackson-Opoku has never been one to twiddle her thumbs and wait for opportunity to find her. In 1997, her first book, The River Where Blood Is Born, was released by Random House. The novel won an American Library Association Black Caucus Literary Award. It also garnered the attention of Jada Pinkett Smith, who listed the book on her Black History Instagram lineup. A second book, Hot Johnny (and the Women Who Loved Him), came out in 2001 and was an Essence Magazine Bestseller in Hardcover Fiction.

During those years, JacksonOpoku raised two children, freelanced, and devoted her time to longer fiction projects. But as her children came of age, she felt the need to stabilize her income and began to teach full time and write

part time.

“It’s hard for me to write while I’m teaching because a lot of that energy goes into teaching...the interaction with students and worrying about them,” Jackson-Opoku said. “I continued to

2025, with a bit of a plot twist. She won the Minotaur Books/ Malice Domestic Best First Traditional Mystery Novel competition in 2023. This achievement led to the publication and release two years later of Savvy Summers and the Sweet Potato Crimes

Jackson-Opoku co-edited Revise the Psalm: Work Celebrating the Writing of Gwendolyn Brooks, which was released in 2017 by Curbside Splendor. In 2022, Lifeline Theatre produced her play

“When I retired from full-time teaching, I just kind of told myself, this is your time. This is the time to try everything.”

— Sandra Jackson-Opoku

write,” publishing travel writing, essays, and short stories, “but it was hard for me to write in the long form,” so longer projects went unfinished.

In 2016, she retired from her university teaching job and returned her attention to projects she had “backburnered.”

Hungry Ghost Festival. Jackson-Opoku also completed numerous shorter works and four novel-length drafts, participated in screenwriting mentorships, and won fellowships and coveted residencies. She had not, however, published a novel in over twenty years. That would change in

The book is set in Woodlawn, where Savvy’s diners belt out lyrical Black witticisms and love on Savvy’s soul food and sweet potato pie. When an elderly man dies after eating a slice of Savvy’s pie, the pendulum of success swings for her restaurant, turning the beloved community eatery and gathering place into almost a ghost town. On top of that, an unscrupulous developer targets Savvy’s property and restaurant for acquisition and gentrification. Faced with these seemingly insurmountable challenges, Savvy could give up, take the paltry funds offered by the developer, and move on. Instead, she becomes an amateur sleuth, rooting out the real killer and shedding light on the developer’s evil doings. Savvy wins in the end, retaining her position as trusted community stalwart and beloved soul food restaurateur.

In just a few months since its launch, Savvy Summers has been eagerly embraced. On August 6, more than forty people showed up to celebrate JacksonOpoku and her new book at Call and Response Books in Kenwood. In addition to the bookstore, the book launch was co-hosted by Jackson-Opoku’s longtime writing group, For Love of Writing, including members Lydia Barnes, April Gary, Janice Tuck Lively, Heather Roberts, and Tina Jenkins Bell, author of this article. Since then, she said requests for appearances to discuss the book have filled her calendar. She’s elated about her book’s reception among readers and in the publishing industry, describing the

positive reviews and book club selections as “an embarrassment of riches.”

While basking in the early successes of her first cozy, Jackson-Opoku is working on a second installation of the Savvy Summers series, Savvy Summers and the Po’boy Perils. Achievements are often hard won, but despite the variety of challenges and the uncomfortable perception of lapsing time, Jackson-Opoku said, she had “to make things work.”

Jackson-Opoku is an author whose literary and historical stories cross borders, oceans, and shores to unravel and reveal the stories of Black people living in the African diaspora. Her focus remained on her work, never aging, until she heard an agent bragging about the youth of a new client.

“That gave me pause because it made me realize this could be a factor in the industry—whether it’s agents... publishers...editors...looking at you and counting up the productive years that they think you have left and possibly making professional decisions based on that,” she said. “So while I have never been a person who was ashamed of my age...I’ve started to be a little reticent.”

Chicago author Maud Lavin, who is close in age to Jackson-Opoku, shares her concern about the industry’s obsession with authors’ book-producing years and public appeal. “You can’t help but internalize some of this stuff. Like I want to do something new, but I’m not exactly thirty-two or living in New York...Screw that. It’s just another trap,” Lavin said. “I love how [Jackson-Opoku]’s dealing with aging. It’s like, ‘What the hell; I’m going to do what I want to do.’”

For decades, the publishing industry has considered literary fiction, with its depth of theme, character, and moral complexities, as “highbrow” and treated genre fiction as “lowbrow” for its formulaic structure, predictability, relatability, and high reader appeal.

Jackson-Opoku, whose first two books were literary novels, grew up reading mysteries and has always loved the genre. Still, she worried about writing them.

“I’ll be honest in that I was a little apprehensive about what people would think about the fact I’ve written and published a work of ‘genre’ fiction, because whatever reputation I have is as a literary writer,” she said. “I also feel like a story

is a story. Whatever package you put it in, you can get across a message in many different forms. I feel like I’m following in a tradition of literary novelists who move back and forth very easily and gracefully between genres—people like Rita Mae Brown [and] Rudolfo Anaya.”

Jackson-Opoku also mentioned Valerie Wilson Wesley, whom she met years ago, and Native American author Sherman Alexie as accomplished writers who crossed from literary to genre fiction, including mysteries. Wesley and Alexie carved a path for other writers, wanting to let the story dictate the genre: “It’s kind of creative permission to experiment,” Jackson-Opoku said.

Tracy Clark, a Chicago-based author of eight mystery novels, finds the genre division inauthentic. “I try not to put a label on it...I’m okay with genre fiction. People denigrate the term, thinking it’s a lower quality of writing. It’s not,” she said. “The division between literary and genre is a marketing thing. It’s just them trying to figure out where to put you on the bookshelf. Writers shouldn’t have to

Though she was unsure about the form, she moved forward, recognizing she had a character, a situation, “the whole idea of food,” and a setting.

Cozy mysteries are easily digestible and typically feature amateur (usually white) sleuths solving off-page murders in quaint settings in English or New England towns. But Jackson-Opoku grew up on Chicago’s West Side and has lived most of her adult life as a South Sider, in Hyde Park and Woodlawn. Wanting to write a “cozy” with familiar characters and settings, she treated hers in the true tradition of Black women in the kitchen, cooking “to taste” and adding a little bit of this and a twist of that as needed, never measuring or referring to a cookbook.

“Sandra’s book instantly made me feel like, ‘This feels like home. These are people I know. People I recognize,’” Clark said.

Despite the challenges of ageism, publishing biases, and cozy industry expectations, Jackson-Opoku joined the ranks of other BIPOC cozy mystery authors, such as Mia Mansala, Valerie Burns, Esme Addison, Vivian Chien, Gigi Pandian, Abby Vandiver, and the late Barbara Neely. She’s done things her way and is happier for it.

worry about that; they should concern themselves with character and story. That’s it...That’s our job.”

“Sandra is hard to pigeonhole. She can write anything. If she wants to write literary, she can write literary. If she wants to write a poem, she can write a poem. If she wants to write cozy mysteries, like she’s doing with this series, that’s fine, too. But you have to sort of allow yourself this freedom to write whatever speaks to you,” Clark added.

Jackson-Opoku considered writing Savvy’s story in different ways before settling on a cozy mystery. At first, she thought it might be a nonfiction depiction of her female relatives’ Great Migration journeys or a memoir.

“But that started to be very research heavy, and I didn’t know if I was prepared to do that kind of excavation into family history,” Jackson-Opoku said. “There’s a lot of the people born in Mississippi that I don’t know, and relatives didn’t always want to talk about it. Some of those memories were painful or pragmatic—we’ve got to deal with what’s in front of us.”

“It’s life-affirming and survivalaffirming that Sandra did this, [and] did it really well,” Lavin said.

“When I retired from full-time teaching, I just kind of told myself, this is your time,” Jackson-Opoku said. “This is the time to try everything, or as many things as you’ve wanted to try. I’ve always wanted to write for film and television, I’ve always wanted to write a play, and I’ve always wanted to write a mystery novel. So whether I succeed or fall on my face in any of those endeavors, it’s not for lack of trying.” ¬

Tina Jenkins Bell is a freelance journalist, published fiction writer, playwright, and literary activist. Her stories “Kaiko” and “The Avalon Haint” were respectively published in The Overturning (Hypertext) and Red Line: Chicago Horror Stories (From Beyond Press) anthologies. Her play Death of a Marriage is a part of Definition Theatre’s Amplify New Plays program. Bell last wrote for the Weekly in June 2023 when she reported on artist Kee Merriweather’s works’s depiction of a future without environmental racism.

Despite having fewer reported incidents than the city average, migrant shelters saw more domestic violence arrests during the two years they operated.

BY WENDY WEI

This story was supported by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism. It was also produced with the support of Blue Shield of California Foundation, working to change the conversation about domestic violence, and The Pivot Fund, investing in journalism by and for marginalized communities.

Residents of Chicago’s migrant shelters were arrested more often than average when police responded to domestic violence calls there, despite having a lower rate of incidents than the citywide average. Records reviewed by the Weekly show that in 2023 and 2024, police arrested residents in 33 percent of domestic violence responses at migrant shelters, nearly double the 18 percent arrest rate citywide during the same period. The city has since closed migrant-only shelters, but questions remain about how domestic violence is handled in its new unified shelter system.

Controversial policies at multiple levels contributed to the disparity. Our year-long investigation revealed that conditions in the city’s migrant shelters violated international safety guidelines, and, in a break from state policy, the Chicago Police Department prioritized making an arrest during domestic violence incidents, despite evidence that arrests do not keep survivors safe.

Domestic violence affects one in four women nationwide. Over the past two years, Chicago police responded to an average of 2,000 domestic violence calls every month. Due to the restrictive, crowded nature of the migrant shelters, residents regularly faced violence in them.

Carmen Medina, thirty-six, was barely asleep when her teenage son’s voice woke her in the middle of the night. She blinked her eyes open to the bright overhead lights that illuminated her room at all times.

Careful not to disturb her husband, their other two sons, and the four families that shared the room, Medina gingerly got up to accompany her son to the bathroom, which she didn’t feel comfortable letting her children use alone. She didn’t have to worry about accidentally squeaking the door open; they were never closed so security could conduct rounds.

Medina, a Venezuelan mother of three who lived with her husband and family at a city-run shelter in a former Marine Corps building in Albany Park for four months, found it difficult to adjust to the stressful and cramped conditions.

“People were desperate, angry. The

children were hungry,” Medina said through a translator. “It was a tragic and surprising experience. We weren’t used to it.”

The food was often bad. People fought frequently in the dining room. There was little reprieve from their crowded, loud environment. Residents’ movements were restricted so that only those with permission could come and go from the shelter with ease. Over the shelters’ twoand-a-half-year run, Borderless Magazine and the Investigative Project on Race and Equity uncovered a pattern of neglected complaints at shelters citywide.

Chicago’s migrant shelters had the kind of conditions that international

humanitarian organizations warn will foster violence: overcrowding, lack of privacy, and restrictions on coming and going.

Cynthia Nambo, a community advisor to the City Council on best practices for migrant shelter, said that in such tightly controlled and tense atmospheres, violence was inevitable.

“People are scared, so whenever you’re in a situation [where] people don’t have resources and they don’t have their own space, [violence] will occur,” said Nambo, drawing from her work as a security advisor at volunteer-run shelter Todo Para Todos.

International humanitarian organizations have grappled with domestic

violence in refugee settings for decades. Since 1991, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has issued guidelines on preventing genderbased violence, of which domestic violence is a form, in camp settings.

Many of the recommendations are specific: Mixed-sex family shelters should provide designated spaces exclusively for women and children, ensure adequate private space for families, maintain proper lighting in shower areas, and employ staff trained in gender-based violence prevention and response. The UNHCR notes that overcrowding can exacerbate tensions and contribute to domestic violence.

Chicago’s migrant shelters failed to meet several of these basic standards, especially those related to overcrowding and lack of privacy for families.

Physical and verbal fights between

couples were common, Medina said.

Though she’d never witnessed it herself, Medina heard many stories where a couple’s fight would end in police taking one of them away.

According to records obtained by the Weekly, at least ninety incidents of intimate partner violence were reported to police at city and state-run migrant shelters between August 2022 and December 2024. Most resulted in no prosecution, often because the survivor refused to press charges. However, a third did result in an arrest. Citywide, fewer than one in five calls resulted in an arrest.

Domestic violence survivors face unique challenges when interacting with law enforcement that differ from other crimes. Survivors often maintain economic and familial ties to their abusers. In many cases, they do not want their partners

down the line,” Goodmark said.

The elevated arrest rates at city shelters reflected federal policy on how police should respond to domestic violence calls, yet broke from the Illinois Domestic Violence Act (IDVA) language that advocates for discretionary arrest.

The Weekly obtained eight versions of policy manuals distributed to shelter staff by the Department of Family and Support Services (DFSS) between August 2023 and July 2024. The documents show that while domestic violence procedures became more detailed, critical gaps remained.

What endured was the reliance on law enforcement to end domestic disputes. The manuals all required shelter staff to call 911 when violence occurred.

Before the 1990s, the criminal justice system considered domestic violence a private matter that should be settled between the couple. The 1994 Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) required police to make an arrest whenever they had probable cause to do so in a case involving domestic violence, in what is known as “mandatory arrest.” As a result, arrest rates for domestic violence more than doubled in the decades that followed its passage.

arrested. They just want the violence to stop.

Leigh Goodmark, the Marjorie Cook Professor of Law at the University of Maryland Carey School of Law, is the author of Decriminalizing Domestic Violence

“We have this picture of safety that says, once we make this arrest, the survivor is safe, and that’s just not true,” Goodmark said at a virtual symposium on domestic violence in September. Incarceration can worsen factors that contribute to abuse; the arrested person may lose a job or access to housing.

Couples living with high financial strain have a higher rate of intimate partner violence compared to those with low financial strain, a rate that some studies pin at three times more.

“So, the thing that we’re doing to intervene is actually going to create the conditions in which violence flourishes

“We don’t do that in any other kind of case; in no other matter do we say, police, you must make an arrest,” Goodmark said. Later iterations of VAWA in 2005 and 2013 softened the language to “preferred arrest,” which means arrest is encouraged but not mandatory. The Illinois Domestic Violence Act specifies that arrest is discretionary, leaving it up to officers to respond to domestic violence incidents as they deem appropriate and granting more autonomy to survivors to advocate for or against the arrest of their abuser.

“The preferred response of the officer is the arrest of the offender,” reads a CPD policy directive on domestic violence calls. “Although the IDVA does not have a mandatory arrest provision, officers are required to use all reasonable means to prevent further abuse…including arresting the offender when probable cause exists.”

For immigrant survivors of domestic violence, the stakes are heightened during encounters with law enforcement. Families navigate an immigration system where any police contact can trigger deportation— potentially for the entire family—or lead to family separations.

Fifty out of the ninety domestic

“F A BUL OUSLY PE RFOR ME D”

violence reports we reviewed involved partners who had children living with them at the shelter.

“A lot of migrants do depend on their partner for stability, whether it’s financial or emotional stability,” said Joel Rivas, a court advocacy supervisor at Mujeres Latinas en Acción. “They do not want to jeopardize having the other person be arrested or deported for those reasons.”

For undocumented people in mixedstatus relationships, domestic violence often involves additional forms of control beyond physical abuse. “It’s very common for abusers to weaponize immigration status and threaten law enforcement contact,” said Anna Hori, a research assistant at the University of Chicago Law School’s Immigrants’ Rights Clinic. “This is a major reason victims don’t come forward.”

Rivas has supported about twenty domestic-violence survivors from migrant shelters over the past two years. None had initially sought police help. While police reports capture cases where law enforcement was contacted, many survivors seek help through hospitals, domestic violence hotlines, and community organizations—pathways that don’t appear in police data. The documented incidents likely undercount actual occurrences of domestic violence in shelters.

The police records from the shelters were a mix of self-reports and reporting on behalf of the survivor by shelter staff or a fellow resident.

Despite the difficult living conditions, Medina said staff’s actions were appropriate. “They did a great job,” she said. “They tried their best and were attentive to the migrants who were not breaking rules.”

Police were often ill-equipped to serve survivors’ needs, according to Rivas. “The language barrier is probably the biggest challenge when communicating with law enforcement for Spanishspeaking migrants,” he said. “It’s common for participants to say that when they call the police, the first responders don’t speak Spanish.”

The couple in their late twenties arrived in Chicago together from Venezuela. For months, they lived with more than 200 other recent arrivals in the volunteer-run shelter Todo Para Todos, where they developed a reputation for having belligerent fights on a regular basis.

Despite multiple altercations, the woman never left her partner, and even helped him sneak back into the shelter after he was banned. But things escalated one afternoon in June 2023. What started as a disagreement grew louder, voices reverberating across their shelter’s common area. Residents had grown used to their arguments, but this time drinking glasses went flying, accidentally nicking a bystander.

By the time Nambo, the shelter’s security lead, arrived, other residents had stepped in, physically separating the pair.

A few escorted the man outside to talk him down. The atmosphere remained tense as families with young children watched nervously.

No one called the police.

“We see police as responders of acute situations, and to prevent death or physical harm that could be damaging for a long time,” said Nambo, drawing on her experience as a principal at an alternative high school. Instead, volunteers at Todo Para Todos relied on community intervention to prevent violence from escalating to that point.

"There’s a power dynamic when we’re from the country, we know English, we know the systems, and our participants don’t know that,” said a volunteer who witnessed multiple domestic violence incidents at the shelter.

Central to the model was respecting survivor autonomy, even when volunteers disagreed with their decisions. “We cannot force her to be separate from him,” Nambo said.

The man returned to the shelter with the help of other residents several days after his ban. This time, things got really out of control. According to police reports and volunteer witness accounts, he hit his girlfriend in the face—an acute situation that rose to the point where police were called. The incident would eventually appear in CPD records in August 2023.

Todo Para Todos closed in September 2023.

Volunteers eventually found apartments for more than 260 people, including the couple. They do not know the whereabouts of the couple today. According to one volunteer, they eventually separated. Chicago’s migrant shelter system closed in December 2024. The CPD’s domestic violence arrest policy remains.

National policies under VAWA continue to tie essential community response funding to mandatory or preferred arrest approaches, despite research showing these policies may exacerbate the very problems they aim to solve. States receiving VAWA funds must allocate at least 25 percent for law enforcement and 25 percent for prosecutors.

In 2023, $3.4 million of Illinois’s federal funding for domestic violence prevention went to law enforcement and courts while $1.7 million went to survivors services.

Under President Donald Trump’s second administration, even these resources are in jeopardy, especially for migrant survivors of domestic violence. One of the first executive orders Trump signed prevents federal funds from being used for “illegal DEI,” which will make it more difficult for organizations that focus on immigrant populations, like Mujeres Latinas en Acción, to apply for grants. The National Domestic Violence Hotline removed migration-specific services and data this year.

In September, ICE detained two individuals outside Cook County’s domestic violence court, reinforcing concerns that seeking help might trigger immigration enforcement. Further, The 19th reported a significant decline from January to March in new applications for the U visa—the specific visa meant to encourage survivors of domestic violence and other serious crimes to come forward by easing their fears of being deported. Advocates say this reflects fear of deportation among those registered with the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services agency.

Local funding is also taking a hit. Mayor Brandon Johnson’s proposed 2026 city budget includes a 43 percent cut in funding for gender-based violence survivors and service providers, according to The Network, a survivor advocacy organization.

The Mayor’s Office disputed that, saying the 43 percent figure was not accurate.

Chicago’s new One System Initiative, which merged migrant and homeless shelters in January, has capacity for 7,400 beds—asylum seekers alongside other vulnerable residents across five locations. The Weekly found four additional domestic violence reports in the first months of 2025 involving residents of both foreign and American backgrounds.

City officials did not respond to requests for comment about whether training protocols have changed or what steps are being taken to address the policy gaps that led to higher arrest rates in the migrant shelter system.

“We need to de-emphasize the criminal system’s response to intimate partner violence, and we should look at it as an economic problem, as a public health problem, as a community problem,” Goodmark said. “As a human rights problem.” ¬

Wendy Wei is an independent journalist and audio producer covering migration and interracial solidarity. She is the Investigative Project on Race & Equity’s training coordinator.

En

los refugios para inmigrantes de Chicago se registró menos violencia doméstica que en el promedio de la ciudad, pero un mayor número de arrestos.

Esta investigación fue apoyada por una beca del Fund for Investigative Journalism. También fue producida con el apoyo de Blue Shield of California Foundation, que trabaja para cambiar la conversación sobre la violencia doméstica, y de The Pivot Fund, que invierte en el periodismo hecho por y para comunidades marginadas.

Los residentes de los refugios para migrantes en Chicago fueron arrestados con más frecuencia que el promedio de toda la ciudad cuando la policía respondió a llamadas por violencia doméstica, a pesar de que hubo menos incidentes que el promedio general. Registros revisados por el Weekly muestran que, entre 2023 y 2024, la policía arrestó a residentes en el 33% de las respuestas por violencia doméstica en los refugios para migrantes, casi el doble del 18% registrado en toda la ciudad durante el mismo período. La ciudad ha cerrado desde entonces los refugios exclusivos para migrantes, pero aún hay preguntas sobre cómo se manejan los casos de violencia doméstica en su sistema One Shelter.

Políticas controvertidas en distintos niveles contribuyeron a esta desigualdad. Nuestra investigación que duró un año reveló que la ciudad creó condiciones en los refugios para migrantes que violaban las reglas de seguridad reconocidas a nivel internacional, rompiendo con la política estatal. El Departamento de Policía de Chicago (CPD) dio prioridad a realizar arrestos durante los incidentes de violencia doméstica, a pesar de que hay evidencia de que los arrestos no garantizan la seguridad de las personas sobrevivientes.

La violencia doméstica afecta a una de cada cuatro mujeres en todo el país. En

los últimos dos años, la policía de Chicago respondió a unas 2,000 llamadas por violencia doméstica cada mes. Por las reglas estrictas y porque los refugios estaban muy llenos, los residentes enfrentaron situaciones de violencia con frecuencia.

Carmen Medina, de treinta y seis años, apenas dormía cuando la voz de su hijo adolescente la despertó en medio de la noche. Ella abrió sus ojos con dificultad bajo las luces brillantes del techo, que permanecían encendidas todo el tiempo. Con cuidado de no despertar a su esposo, a sus otros dos hijos y a las cuatro familias con las que compartían el cuarto, Medina se levantó despacio para acompañar a su hijo al baño, al que no se sentía cómoda dejando ir sola a sus hijos. No tenía que preocuparse por hacer ruido al abrir la puerta. Las puertas nunca se cerraban para que el personal de seguridad pudiera hacer sus rondas. Medina, una madre venezolana de tres hijos que vivió con su esposo y su familia durante cuatro meses en un refugio administrado por la ciudad en un antiguo edificio del Cuerpo de Marines en Albany Park, dijo que le resultó difícil adaptarse a las condiciones estresantes y el espacio tan reducido.

“La gente estaba desesperada, enojada. Los niños tenían hambre”, dijo Medina a través de un traductor. “Fue una experiencia trágica y sorprendente. No estábamos acostumbrados a eso”, La comida sabía mal. La gente peleaba con frecuencia en el comedor. Había poco descanso del ambiente ruidoso y lleno de gente. Los residentes tenían movimientos restringidos: sólo quienes tenían permiso podían entrar y salir del refugio con facilidad. Durante los dos años y medio que funcionaron los refugios, Injustice Watch y

el Investigative Project on Race and Equity encontraron que muchas quejas no fueron atendidas en refugios de toda la ciudad.

Los refugios para migrantes de Chicago parecían haber creado las condiciones que, según organizaciones internacionales, dicen que pueden causar violencia: demasiada gente en poco espacio, poca privacidad y límites para entrar o salir.

Cynthia Nambo, asesora comunitaria del Concejo Municipal sobre buenas prácticas en refugios para migrantes, dijo que en ambientes tan controlados y tensos, la violencia era inevitable.

“La gente tiene miedo, y cuando estás en una situación donde las personas no tienen recursos ni su propio espacio, la violencia ocurre”, dijo Nambo, basándose en su experiencia como asesora de seguridad en el refugio voluntario Todo Para Todos.

Las organizaciones humanitarias internacionales han enfrentado la violencia doméstica en campamentos de refugiados durante décadas. Desde 1991, el Alto Comisionado de las Naciones Unidas para los Refugiados (ACNUR) ha publicado guías para prevenir la violencia de género, de la cual la violencia doméstica es una forma, en estos lugares.

Muchas de las recomendaciones son específicas: los refugios familiares mixtos deben tener áreas separadas para mujeres y niños, ofrecer suficiente espacio privado para las familias, mantener buena iluminación en las zonas de baño y contar con personal capacitado en prevención y atención de la violencia de género. El ACNUR advierte que cuando hay demasiadas personas en un mismo lugar, crecen las tensiones y puede haber más casos de violencia doméstica.

Los refugios para migrantes de Chicago no cumplieron con varias reglas básicas, sobre todo las relacionadas con tener demasiada gente en poco espacio y la falta de privacidad para las familias.

Las peleas físicas y verbales entre parejas eran comunes, contó Medina. Aunque ella no lo vio con sus propios ojos, escuchó muchas historias de parejas donde las peleas terminaban con la policía llevándose a uno de ellos.

Según registros obtenidos por el South Side Weekly , la policía recibió al menos 90 reportes de violencia entre parejas en refugios para migrantes administrados por la ciudad y el estado entre agosto de 2022 y diciembre de 2024. La mayoría de los casos no llegó ante un juez, muchas veces porque

la víctima no quiso presentar cargos. Aun así, una tercera parte terminó con un arresto. En toda la ciudad, menos de una de cada cinco llamadas terminó con una detención.

Las personas que sufren violencia doméstica enfrentan dificultades especiales al tratar con la policía. Muchas siguen dependiendo económicamente o tienen hijos con la persona que las agrede. En muchos casos, no quieren que arresten a su pareja. Ellos solo quieren que la violencia se detenga.

Leigh Goodmark, profesora de Derecho en la Universidad de Maryland y titular de la posición Marjorie Cook, es autora del libro Decriminalizing Domestic Violence. “Tenemos esta idea de seguridad que dice que, una vez que se hace un arresto, la persona sobreviviente está a salvo, y eso simplemente no es cierto”, dijo Goodmark durante un simposio virtual sobre violencia doméstica en septiembre. El encarcelamiento puede empeorar los factores que contribuyen al abuso. La persona arrestada puede perder su trabajo o su vivienda.

Las parejas con más problemas económicos tienen más casos de violencia entre sí que las que tienen menos dificultades. Algunos estudios dicen que ese número puede ser hasta tres veces mayor.

“Entonces, lo que hacemos para intervenir en realidad puede crear las condiciones para que la violencia baje con el tiempo”, dijo Goodmark.

Los altos niveles de arrestos en los refugios de la ciudad reflejan la política federal sobre cómo debe de responder la policía a llamadas por violencia doméstica.

doméstica, lo que también da más poder a las víctimas para decidir si quieren o no que arresten a su agresor.

Sin embargo, esto se aparta de la Ley de Violencia Doméstica de Illinois (IVDA), que recomienda dejar el arresto a discreción de la policía.

El Weekly obtuvo ocho versiones de los manuales de políticas que el Departamento de Servicios Familiares y de Apoyo (DFSS) distribuyó al personal de los refugios.

Lo que se mantuvo fue la dependencia de la policía para resolver los conflictos domésticos. Todos los manuales indicaban que el personal de los refugios debía llamar al 911 cuando ocurría un acto de violencia.

Antes de la década de 1990, el sistema de justicia penal consideraba la violencia doméstica un asunto privado que debía resolverse entre la pareja. La Ley de Violencia contra la Mujer (VAWA, por sus siglas en inglés) de 1994 ordenó a la policía hacer un arresto cuando hubiera razones suficientes para creer que existía violencia doméstica. Esto se conoce como “arresto obligatorio”. Como resultado, el número de arrestos por violencia doméstica se duplicó en las décadas siguientes.

“No hacemos eso en ningún otro tipo de caso; en ningún otro asunto decimos: ‘Policía, deben hacer un arresto’”, dijo Goodmark. Las versiones más recientes de la Ley de Violencia contra la Mujer (VAWA), en 2005 y 2013, cambiaron el lenguaje a “arresto preferido”, lo que significa que se recomienda arrestar, pero no es obligatorio.

La Ley de Violencia Doméstica de Illinois establece que el arresto es discrecional, es decir, deja en manos de los oficiales decidir cómo actuar ante un caso de violencia

“La respuesta preferida del oficial es arrestar al agresor”, dice una directiva del Departamento de Policía de Chicago (CPD) sobre llamadas por violencia doméstica. “Aunque la Ley de Violencia Doméstica de Illinois (IVDA) no incluye una disposición de arresto obligatorio, los oficiales deben usar todos los medios razonables para evitar más abusos…incluyendo arrestar al agresor cuando exista causa probable”, Para las personas migrantes que sobreviven a la violencia doméstica, los riesgos aumentan al tener contacto con la policía. Las familias enfrentan un sistema de inmigración en el que cualquier encuentro con las autoridades puede provocar una deportación—posiblemente de toda la familia—o una separación familiar. De los 90 reportes de violencia doméstica que revisamos, 50 involucraron parejas con hijos que vivían con ellos en el refugio“. Muchos migrantes dependen de su pareja para mantenerse estables, ya sea económicamente o emocionalmente”, dijo Joel Rivas, supervisor de apoyo legal en Mujeres Latinas en Acción. “Por eso no quieren arriesgarse a que la otra persona sea arrestada o deportada”. En las parejas con estatus migratorio mixto, la violencia doméstica muchas veces incluye otras formas de control además del abuso físico. “Es muy común que las personas agresoras usen el estatus migratorio como una amenaza y digan que llamarán a las autoridades”, explicó Anna Hori, asistente de investigación en la Clínica de Derechos de los Inmigrantes de la Facultad de Derecho de la Universidad de Chicago. “Esa es una de las principales razones por las que muchas víctimas no denuncian”. Rivas ha apoyado a unas veinte personas sobrevivientes de violencia doméstica que vivían en refugios para migrantes durante los últimos dos años. Ninguna buscó ayuda de la policía al principio. Aunque los reportes policiales muestran los casos donde hubo contacto con las autoridades, muchas víctimas buscan apoyo en hospitales, líneas de ayuda para violencia doméstica y organizaciones comunitarias, caminos que no aparecen en los datos de la policía. Por eso, los casos registrados probablemente no reflejan la cantidad real de incidentes de violencia en los refugios. Los reportes de la policía de los refugios

eran una mezcla de denuncias hechas por las propias víctimas y de reportes hechos por el personal del refugio o por otros residentes. A pesar de las difíciles condiciones de vida, Medina dijo que el personal actuó correctamente. “Hicieron un gran trabajo”, ella dijo. “Dieron lo mejor de sí y fueron atentos con los migrantes que seguían las reglas”.

Según Rivas, la policía muchas veces no estaba preparada para atender las necesidades de las víctimas. “La barrera del idioma es probablemente el mayor problema cuando los migrantes que hablan español intentan comunicarse con la policía”, dijo Rivas. “Es común que digan que, cuando llaman, los primeros oficiales que llegan no hablan español”.

La pareja, de unos veintitantos años, llegó junta a Chicago desde Venezuela. Durante varios meses vivieron junto a más de 200 recién llegados en el refugio administrado por voluntarios Todo Para Todos, donde se ganaron la reputación de tener peleas fuertes con frecuencia.

A pesar de las múltiples discusiones, la mujer nunca dejó a su pareja e incluso la ayudó a volver a entrar al refugio después de que se le prohibiera la entrada. Pero todo se salió de control una tarde de junio de 2023. Lo que comenzó como un desacuerdo se intensificó , con las voces resonando en el área común del refugio. Los demás residentes ya estaban acostumbrados a sus peleas, pero esta vez volaron vasos y uno alcanzó a golpear por accidente a otra persona.

Cuando Nambo, encargada de la seguridad del refugio, llegó al lugar, otros residentes ya habían intervenido y separado a la pareja. Algunos acompañaron al hombre afuera para tranquilizarlo. El ambiente seguía tenso mientras las familias con niños pequeños miraban asustadas.

Nadie llamó a la policía.