Honi Soit

Two Years of Genocide

4

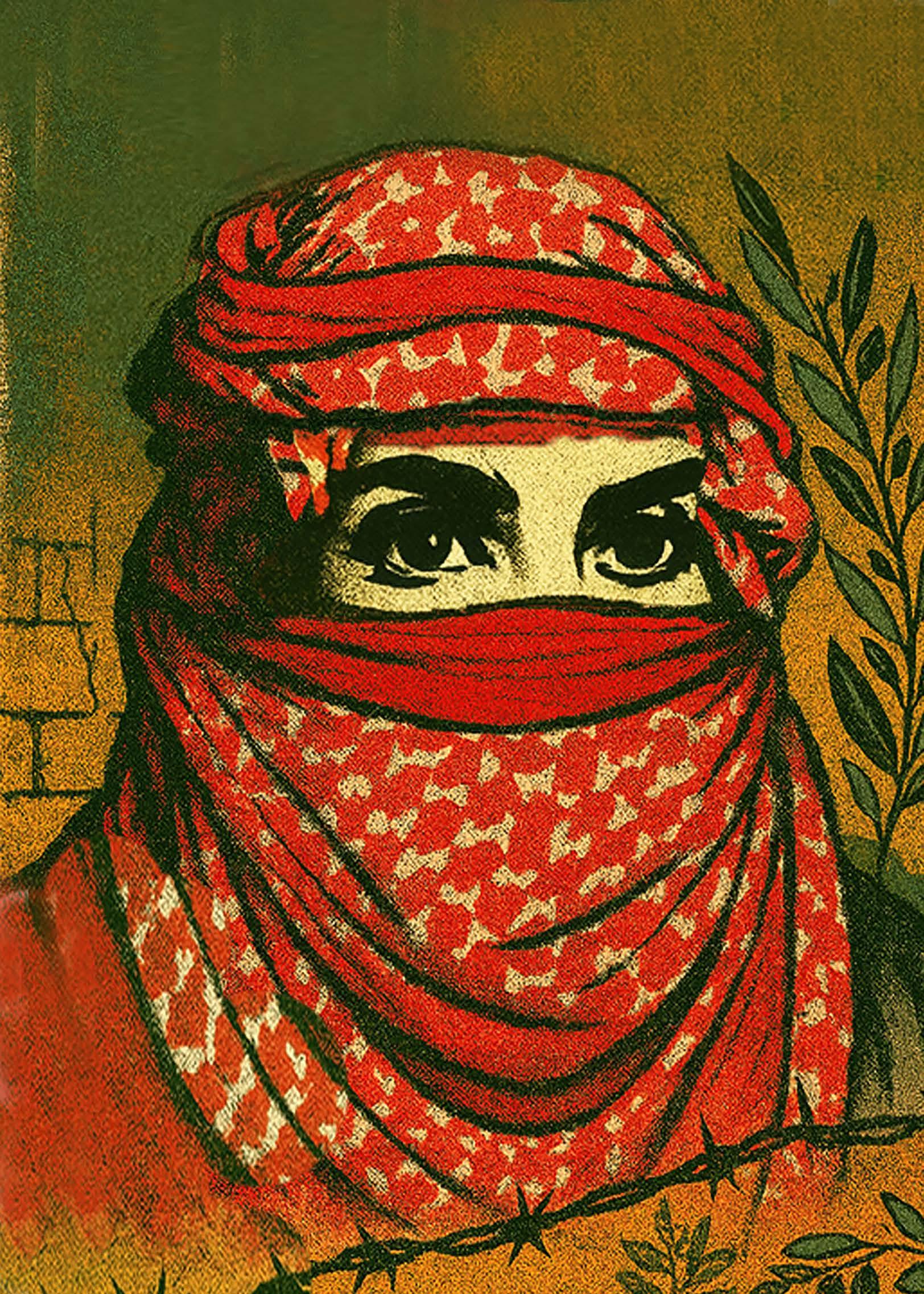

Liberation in Jaseena’s Palestine

, Wake Me Up When the Birds Sing Again

Two Years of Genocide

4

Liberation in Jaseena’s Palestine

, Wake Me Up When the Birds Sing Again

Honi Soit operates and publishes on Gadigal land of the Eora nation. We work and produce this publication on stolen land where sovereignty was never ceded. The University of Sydney is a colonial institution. Honi Soit is a publication that prioritises the voices of those who challenge colonial rhetorics. We strive to continue its legacy as a radical left-wing newspaper providing students with a unique opportunity to express their diverse voices and counter the biases of mainstream media.

Editors

Jaseena’s Palestine

Stujocon <3

Ft. Filipino Stujo

Kashmir Under Fire

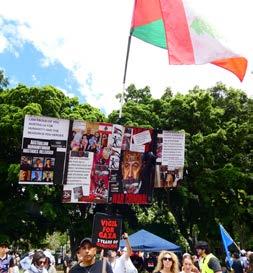

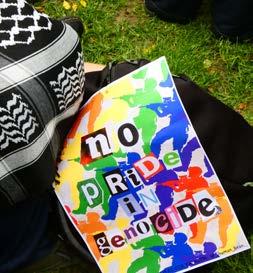

This week marks two years that Israel has spent bombing Gaza, in its illdisguised effort to systematically eradicate the Palestinian people. Those who cannot see the genocide as it trudges ever onward lack not only eyes, but a heart.

Today, I marched with my co-editors at the Nationwide March for Palestine. We saw tens of thousands of people attend, to protest against the genocide, the detainment of the Sumud Flotilla activists, and Israel’s terror-fuelled occupation. The Palestinian Genocide has changed the world, and divided it into two groups: those who watch and those who act. I hope that these readers are in the latter category.

and Randa

Comedy

In the spirit of Palestinian freedom, I chose to give this edition the theme ‘Liberation’. Within these pages, you will find the exquisite feature written by Jaseena Al-Helo, describing a life that she could have lived in a Free Palestine. You will see many languages — including Arabic, Mandarin, Greek and more —

because our multilingual reporters don’t get enough opportunity to show off their skills. Read Anonymous’ piercing analysis into the Pakistani occupation of Kashmir, Meijie Ureta’s exploration into international campus press freedom, and Kira Kwong’s analysis of the death (or not) of Cantonese. Keep an eye out for an interview by myself and Mehnaaz with Randa Abdel-Fattah, on the normalisation of Australian apathy during a genocide.

One unusual thing about this edition is that it’s got student journalists from outside Honi. We have talked a lot this year, and in years prior, about increasing Honi’s connections with other publications, and with establishing a national network of student media who actually know each other, read each other’s publications, and contribute to a shared sense of community. During my term I have been very fortunate to watch this unfold before my eyes, both during the 2025 Student Journalism Conference, which I directed, and in the creation of the

Companion Piece, Mina Malekpour

In a world where men have time and again failed to uphold humility, humanity, and freedom, we now find ourselves at the close of a catastrophic war of greed and extremism. If we paid a little more attention, showed a little more kindness, and exercised a little more patience, perhaps we could still avert the ruin that looms.

Purny Ahmed, Mehnaaz Hossain, Ondine Karpinellison, Ellie Robertson, Imogen Sabey, Charlotte Saker, Will Winter, Victor Zhang

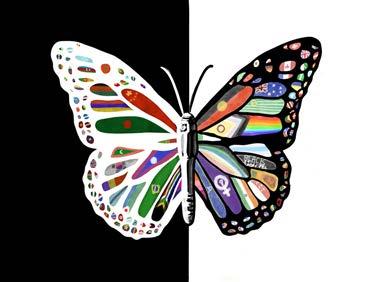

Front Cover

Mina Malekpour

There will never be peace in this world if we continue to treat each other as enemies. We may not share the same ideologies, we may not come from the same class structures, and we may not have the same skin colour, but we will all take our final breath on this earth. And that, perhaps, is the greatest and truest unity of humankind.

Student Media Association, of which I am the inaugural president. Student media is a very fragile world, but it is so precious to me, and I hope that this network and momentum can continue long after I leave university. You can read about some of the StuJoCon events on p. 12 — there are a lot of them, so it’s four pages. Enjoy.

Much like many Honi editors before me, it’s with a heavy heart that I present this edition to you. Honi has entirely changed my life. It’s hard to convey just how much I love this newspaper and the people who have made it with me. It has made me a better person, challenged me in ways I could not have foreseen, and given me random gifts at zero notice in the style of a benevolent tsunami. Thank you for reading, and thank you for caring. Thank you also to Purny for being a gun with art, among other things.

Finally, thank you to my team. Out of all the good things that I gained this year, the best thing was you.

Please, be kind, to one another, to animals, to nature.

And don’t forget to wear sunscreen.

Jaseena Al-Helo, Anonymous, Sath Balasuriya, Riley Bampton, Calista Burrows, Mehar Chugh, Pia Curran, Siena Fagan, Ethan Floyd, Kayleigh Grieg, Mahtab Hassanzadeh, Audrey Hawkins, Mehnaaz Hossain, Gracie Hosie, Ondine Karpinellison, Ting Ken Kuo, Kira Kwong, Alan Lau, Georgie McColm, Kiah Nanavati, Jenna Rees, Imogen Sabey, Jessica Louise Smith, Gabrielle Tan, Sahiba Tasnia Tanushree, Meijie Ureta, Ingrid Winter, Will Winter, Simone Wong, Eryn Yates, Victor Zhang

Artists

Purny Ahmed, Charlotte Saker, Will Winter

Hi there,

You have probably received thousands of emails very similar to this one, but regardless,

I was very disappointed to find out that you had themed Week 8’s Honi around God and the Abrahamic religions, but you didn’t once refer to the paper as “Holy Soit”.

I mean, come on. The pun was right there.

More crappy puns in Honi 2026.

Ishtar

Dear Honi,

After observing the elections and seeing those grassroots Independents exposing the Labor students... I sometimes think, what utility does being in NSW Labor students serve battling it out for the SRC beyond their careerist ambitions for CV padding? After all, it’s the only arena where they are the centrists and they must fight the left. In real politics its out and about right wing fucks you must contest.

Then I realised... they’re cutting their teeth for when they have to fight the left inside their party (Fergs) and the left from outside (Greens, NSW Socialists), and also learning to deal with Liberals for bipartisan legislation to fuck workers. It’s ALL applicable to their future careers... Much to consider.

Anonymous

Dear editors,

I have been under a rock for four years now, and since my arrival in Australia, I’ve been able to avoid the Guardian’s Australian Bird of the Year competition every time. I’m not into birds, I’m not into competitions, nor am I into general public upheavals.

However, your persistent campaigning for the Tawny Frogmouth has inspired me to do my research and get involved. My initial thoughts around the bird that I would go for was the Bush Turkey. I thoroughly enjoy their history of resistance to extinction, and personally, I think Honi should hone in on that radicalism a little more. Besides this point, I have been converted to be a Tawny endorser (I was bribed).

Its beady eyes and old man energy is endearing, cute, and wholesome. I feel safe around Tawny. I feel loved by Tawny.

I feel that my world revolves around Tawny, and that is the doing of Honi

If you, the reader, are thinking about voting in the competition, I fully implore you to vote for Tawny.

Love and wings, ER xxx

Dear ER,

I love you. Thank you so much. Have you voted today?

Lots of love,

IS

Dear Honi

It’s clear that your beloved Tawny Frogmouth is en route to a landslide and I’d just like to ask: how do you sleep at night?

I’m not talking about the incessant hooting made by Tawny Frogmouths from sunset to sunrise. I mean your choice to platform such a mainstream opinion. I thought student media was here to give a voice to the little guy?

The Willie Wagtail, for example. They’re certified little guys: only 18-22cm long and tipping the scales at just 18 grams. And how can you not love their happy little dance?

As the nation embraces the Tawny Frogmouth, I hope you’ll remember to give this underdog - or underbird, as it were - a chance.

Signed,

Team Willie Wagger (The Tert)

Dear Tert,

You guys need to work on your campaign. I mean, really, where are your howto-vote cards? Your elaborate campaign stunts? Your presidential endorsements?

The Tawny is a sleepy eepy ball of fluff, cuddling with its family at all hours of the day and night, just like us. When it comes to the bird that will stick around for you, there’s only one answer: Tawny.

claim a victory prematurely. Nevertheless, we shall remain persistent and steadfast in support for our beloved Tawny.

Signed,

Team Tawny Frogmouth (Honi Soit)

Send your letters to editors@ honisoit.com

Victor Zhang reports.

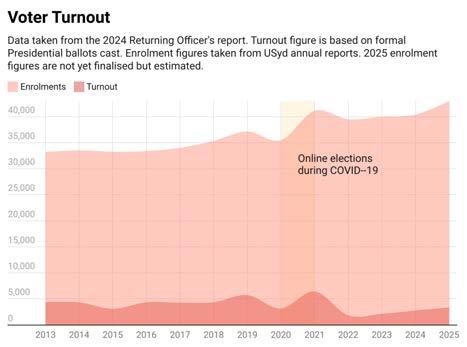

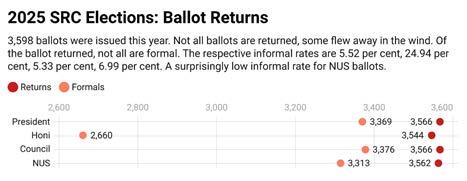

Turnout climbed this year to 3,598 ballots issued. The 2024 Returning Officer’s Report uses the formal ballots cast in the Presidential race to judge historical rates of turnout stretching back to 2013, though obviously in years with uncontested Presidencies this is drawn from a different ballot.

From the 2013 to 2018 era, turnout as a percentage of enrolments averaged a fairly stable 12.24 per cent. COVID-19 and online voting disrupted this stability. The 2022 election, being the first in-person election since COVID-19, saw turnout tank to a record low of 4.68 per cent. Turnout has steadily climbed over the last three years, with this year’s turnout reaching 7.83 per cent (3,369 formal Presidential ballots cast, compared to an enrolment of approximately 43,000).

Presidential and Council ballot informals remained at roughly 5 per cent of ballots cast. Surprisingly, this year the informals for National Union of Student (NUS) ballots almost halved from 12.02 per cent to 6.99 per cent. Understandably, given that there has been no contested Honi elections since 2021 and considering the relative lack of Honi campaigners, one quarter of all Honi ballots cast were informal.

An interesting thing to note is that after the introduction of separate Above-The-Line (ATL) and Below-The-Line (BTL) ballots, there was a drastic drop in BTL Council ballots cast. This year only 39 BTL Council ballots were cast or 1.15 per cent of formal Council ballots cast. Comparatively, when there was no separation between ATL and BTL ballots, there were significantly more BTL ballots cast due to voters unintentionally voting for candidates below-the-line. When voters indicate preferences both above and below the lines, the BTL preferences take precedence over ATL preferences.

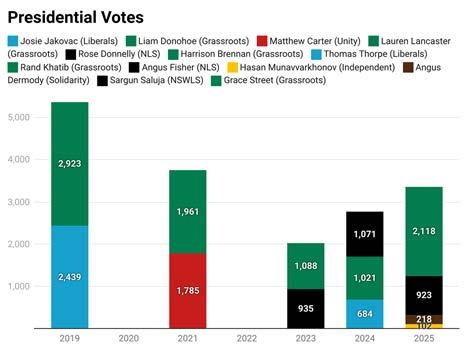

The best predictor for a Presidential candidate’s vote comes down to how many campaigners there are on the ground that are supporting said candidate and how motivated the campaigners are. President-Elect Grace Street (Grassroots) was supported by Grassroots, Socialist Alternative (SAlt), PENTA, and National Labor Students (NLS).

Street’s comfortable lead reflected in the exit poll from the first day to the rest of the election, resulting in her decisive victory. We in fact underpolled Street’s performance, likely due to shy SAlt and PENTA voters.

The Honi election looked more like a three-way race between Burn, Flash, and Informals (still erasing Mop).

There were more informals ballots cast than Flash ballots cast on Fisher Day Two, Fisher Day Three, Susan Wakil, and the Peter Nicol Russell booths. Informals and Flash ballots were tied at Manning and Jane Foss Russell on Day Two. Ooft.

Like presidential ballots, the predictor for which ticket will win is typically the number of campaigners on the ground. Flash fielded no campaigners outside members of their ticket. While Burn had a more energetic campaign with campaigners not on their ticket, the overall Honi campaign was less visible than a presidential or council campaign.

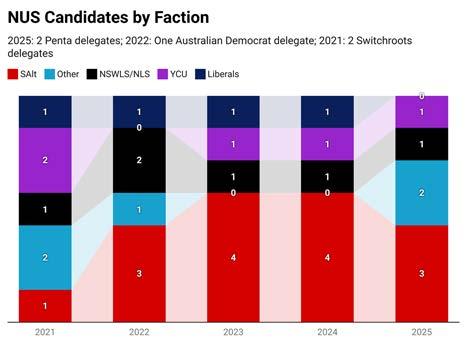

The delegates to the NUS National Conference this year are, in order of election, Sally Liu (PENTA), Jasmine AlRawi (SAlt), Leo Moore (YCU), Bohao Zhang (PENTA), Shovan Bhattarai (SAlt), Lauren Finlayson (SAlt), and unsuccessful President candidate Sargun Saluja (NSWLS).

Compared to previous years, the Liberals did not contest for NUS delegates, instead choosing to preference the ‘IMPACT for NUS’ ticket. PENTA chose to join the fray, securing two delegates to the NUS.

The NUS count proceeded fairly quickly, with six delegate spots elected by Sunday, 28th September. The last three candidates remaining in the race for the seventh delegate were Angus Dermody (Solidarity), Sargun Saluja (NSWLS), and Red Tilly (NLS). Dermody having the lowest vote share of the three by that point was eliminated. While Saluja had a higher vote than Tilly, should Solidarity had explicitly (no pun intended) preferenced NLS, they could have decided the fate of the seventh NUS delegate.

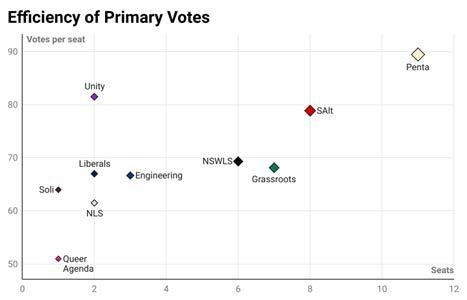

We calculated here the efficiency of each faction’s primary vote share by dividing the primary vote received by the number of seats gained by each faction.

There is a loose correlation between the number of seats gained and votes per seat gained, likely from seats gained by representatives elected over quota.

The obvious comparison we can draw is between Grassroots and Socialist Alternative, with Grassroot’s efficiency being higher than SAlt’s while gaining a similar number of seats. Grassroots opted for the strategy of running a greater quantity of tickets and using preferences to elect and keep their candidates from being eliminated.

However, the choice to run more tickets with clever preferencing does not always result in greater efficiency. PENTA, having run 15 tickets, was in fact the least efficient. Of course, nine of their 11 councillors were elected over quota which obviously puts a dent in the efficiency.

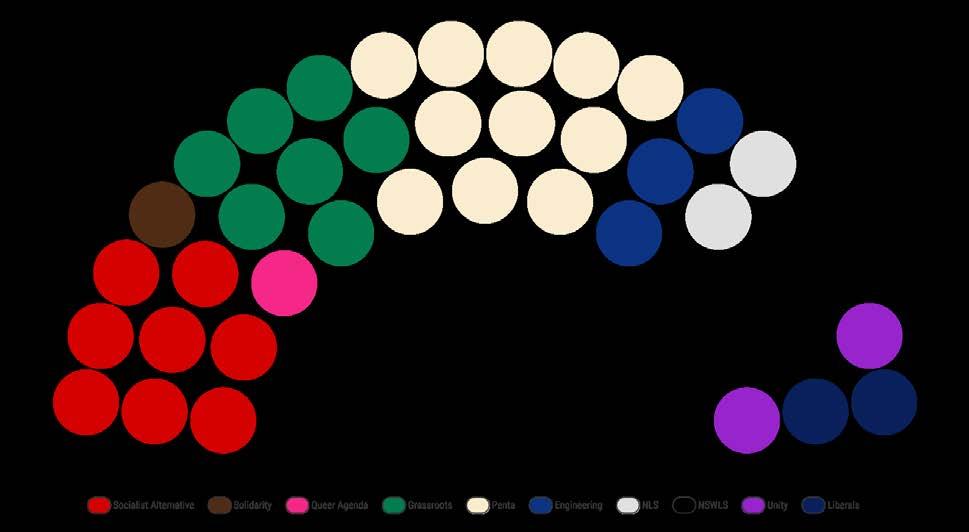

With notice for Reps-Elect given for 29th November, there is likely to be an increased urgency in negotiations where factional headkickers and negotiators carve up the SRC Office Bearer (OB) positions.

22 councillors form a majority, enough to secure the paid positions of Vice-Presidents, General Secretaries, and Education Officers. Where there is more than one position to be elected, the proportional representation method with single transferable vote method is to be used.

This means that 30 councillors are required to secure every other non-autonomous OB position, as there are two positions that may be filled by up to four people. The vote of eight councillors is required to guarantee one general executive position, meaning the next threshold for a leading coalition to secure is 32 councillors to gain 4 general executives.

The pre-election bloc consisting of Grassroots, SAlt, PENTA, and NLS have secured 28 Councillors. As it stands, Honi does not believe there exists any configuration of the left bloc that is not led by Grassroots, SAlt, and PENTA, the three dominant factions on Council (26 seats).

There exists a highly unlikely configuration to form a majority of 24 where the united Labor factions are joined by Engineering for SRC and have done the impossible to convince PENTA to defect, something PENTA has no electoral incentive to do. It is Honi’s view that there is no path for this Labor-led configuration to reach a 30 or 32 councillor majority.

Hopefully this year’s negotiations will produce a deal signed well ahead of one hour into Reps-Elect.

I hereby declare the following candidates elected: President Grace STREET

Editors of Honi Soit

BURN FOR HONI: James Fitzgerald Sice, Kiah Nanavati, Ramla Khalid, Madison Burland, Sebastien Tuzilovic Condon, Marc Panesa, Faye Tang, Anastasia Dale, David Jeremy Salazar Bautista, Kuyili Karthik.

Representatives to Council Quota = 54

Sincerely, Riki Scanlan, 2025 SRC Electoral Officer

Imogen Sabey reports.

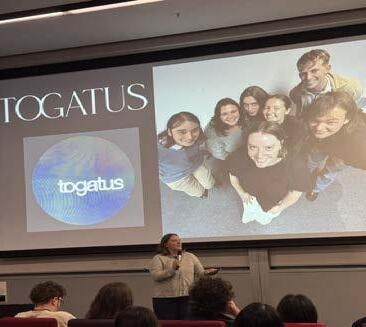

The Student Media Association (SMA) has been formally established, marking Australia’s first-ever union of student media.

The idea for the SMA came into being during a plenary at the 2025 Student Journalism Conference, where panellists and audience members were discussing how to maintain and improve ties between student publications.

According to the SMA constitution, its aims are:

1. To advocate on behalf of student media publications to stakeholders in the higher education sector including universities, the NUS and student unions,

2. To enable communication, information-sharing, and community-building between student journalists, student media organisations, and publications,

3. To support publications facing censorship, funding cuts, and other risks to continued operations, and

4. To promote students’ contributions to culture, arts, and journalism.

The SMA will be governed by a board consisting of seven members. Those members will be elected each year, having been nominated as a representative of their publication. In the years following 2026, the Immediate Past President will be on the board as a non-voting member.

The inaugural board is as follows:

President: Imogen Sabey (Honi Soit, NSW)

General Secretary: Riley Bampton (Glass, QLD)

Vice-President, News: Max Richter-Weinstein (Noise, NSW)

Vice-President, Culture: Mandy Li (Lot’s Wife, VIC)

Vice-President, Advocacy: Joseph Mann (Woroni, ACT)

Small & Regional Officer: Evelyn Unwin Tew (Togatus, TAS)

Multimedia Officer: Georgie McColm (Radio Monash, VIC)

Some of the roles such as the Small & Regional Officer and the Multimedia Officer require specific qualifications; respectively, that the Small & Regional Officer come from a publication less than five years old or from a university based in a regional area or with a small student population, and that the Multimedia Officer come from a publication that primarily produces multimedia content, beyond the scope of print media.

The establishment of the SMA has been inspired by the College Editors’ Guild of the Philippines (CEGP), a

At 2:55pm on 9th October, Honi received reports of ‘abortion abolitionists’ on the Camperdown campus. The demonstration was located on the City Road footpath near the F35 building.

Two men stood on the footpath with three graphic antiabortion signs. One of the signs read “What about my bodily autonomy?” and depicted the silhouette of a baby constructed from blood clots.

The self-identified ‘abortion abolitionists’ had two tripods and cameras set up on either side of their demonstration. Both cameras, whose total range would capture every pedestrian crossing City Road into Eastern Avenue, were likely to be actively filming. It’s unknown what the purpose of this footage was, or if there was intention for it to be public.

After no reports of security or Campus Access Policy (CAP) intervention for over twenty minutes, Honi called campus security at 3:20pm. Campus security informed Honi that they had “just seen them on CCTV” and would be dealing with them shortly.

Honi followed up with campus security at 3:44pm, who said that an Operations Controller had been deployed to the site. Honi was informed that security was unable to take action as the demonstration was not technically on campus, since “the footpath is council property.” Campus security then told Honi that they would be calling the police.

These individuals were identified by campus security as the same people who demonstrated last semester on 28th May. At that time, police were deployed and they issued a move-on order. The police are unable to ban people from a public space.

At the time of publication, 4:45pm, the ‘abortion abolitionists’ were still onsite at the university. There was no police presence.

student media union that has existed in the Philippines since 1937.

The CEGP was represented at the Student Journalism Conference by the LaSallian, based at the De La Salle University in Manila. The 2025 Conference marked the first occasion where an international student publication participated in an Australian student media conference.

In a comment to Honi, SMA President Imogen Sabey said “This is a really exciting time for the student media community, and it’s a great way to build momentum on the amazing conference that we’ve just had. It’s a privilege to serve as President in 2026, and I look forward to seeing what we can do to improve connections and resourcesharing within this network, building upon the work of previous years.

“With the crises that are unfolding around us like the genocide in Gaza, as well as corruption and censorship in our universities, I think it’s never been a more important time to be a student journalist. We have never tested how strong we are when we come together, and the formation of this union will be a turning point for student media.”

The SMA’s constitution is available for public access via @studentmedia.au on Instagram.

Student media organisations can apply for membership by registering online.

If you or any of your loved ones have been affected by the issues mentioned in this article, please consider contacting the resources below:

NSW Sexual Violence Helpline – Provides 24/7 telephone and online crisis counselling for anyone in Australia who has experienced or is at risk of sexual assault, family or domestic violence and their nonoffending supporters. The service also has a free telephone interpreting service available upon request.

Safer Communities Office – Specialist staff experienced in providing an immediate response to people that have experienced sexual misconduct, domestic/ family violence, bullying/harassment and issues relating to modern slavery.

Wirringa Baiya Aboriginal Women’s Service – Provides legal advice and sort for a range of issues, including domestic, sexual, and family violence, to Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander women, children and youth.

1800RESPECT – A service available 24/7 with counsellors that supports everyone impacted by domestic, family and sexual violence.

Lifeline – 24/7 suicide prevention crisis support hotline for anyone experiencing a personal or mental health crisis.

What if I had been born there?

Not here, on sandstone steps beneath jacarandas, but in al-Quds القدس, where the stones breathe centuries and the air still tastes faintly of tear gas? What if my first word was not hello, but marḥaba مرحبا? Would I still be writing this piece, or would I have already lived it into my bones?

Here, in Sydney, the cursor blinks like a pulse. I write in the coloniser’s tongue because it’s the only one I can shape without stumbling. My essays wear legal citational footnotes like armour, neat and obedient — as if a citation can save me. I flatten my vowels, sand down the edges of my rage, learn to be the articulate “good student,” because anything else reclassifies me: angry, Arab, woman. Somewhere a uniform insists on calling it a “defence force.”

I edit the sentence: occupation. Israeli Occupation Force.

There. True on the page, even if it is dangerous in the mouth.

On the other side of the mirror — no, not a mirror; let’s call it a threshold — there is a version of me who never left. I do not name her, not yet. All I see are notebooks filled with slanted Arabic, ink thickenings where her لَم (qalam) pressed too hard. She knows the smell of stone after rain, the pace of the Old City when the call to prayer bleeds into church bells. She does not cite like I do; her sources are olive wood, market dust, a checkpoint mapped on the body.

Between us, a question begins to braid: what does liberation mean when it keeps

changing shape each time we say it aloud?

I could end the opening there and be polite. But I promised myself I would not write a polite piece.

Liberation.

Everyone says it like a slogan, a chantsized word, neat enough for poster font.

But what is it, really?

We’ve done it all.

Protests – marched until our throats bled.

Boycotts – checked shopping lists like prayer beads.

Recognition – flags raised in hollow halls.

Doctors flown in, aid shipped out, hashtags trending.

Done. Done. Done.

And still Gaza burns.

And still lethal signatures land like routine paperwork.

And still a company announces “innovation” in the same breath as occupation – drones, delivery, dividends.

And the world calls it progress. I call it profit from a wound.

So tell me: how exactly do you expect me So tell me: how exactly do you expect me to believe in liberation?

I am twenty. I thought I had already seen the worst.

When my apartment in Ramallah was tear-gassed, I thought that was the worst.

When a rifle’s red dot pinned my body at a checkpoint between Jordan and Palestine, I thought that was the worst.

It was the summer of 2019. We left the borders of Jordan just after maghrib, the sky bruised purple, my bag the cheap turquoise one Tayta bought at the market, and what should have been a two-hour drive folded into something else: ten hours, the sun and moon swapping places while we sat in waiting rooms that smelled of disinfectant and fear. We reached home at adhan alfajr, all of us hollowed and valanced in ways that paperwork could not name.

When they called my name it came like a pronouncement. Two soldiers ushered me into a cold back room — concrete, a single swinging bulb, a chair that scraped the floor like a clock. One of them had a beard that curled at the chin, stubble silver against olive skin; you could see where the razor missed in the morning. I remember the way his breath smelled of cigarette ash and metal, like old radios and lighter fluid. He asked the same rehearsal of questions, the ones that have answers and the ones that don’t: Why are you here? Where did you stay? Who are you visiting? Their voices were flat, practiced. Their hands rested on a table that had seen better decades.

They made me stand. They made me open my bag – just my old iPhone X and a journal and watched me take out the same things I always travel with: passport, small packet of tissues, a note from Mama with her handwriting that always slants like a prayer. Each item became evidence. Each breath I took was parsed. The light in the room felt like a verdict.

Outside, in the bus, Baba and Jido shouted at the soldiers for keeping us held up and separated. Inside, the guard asked me to name places they already knew by heart. The humiliation was slow and exacting, a measured erosion.

When my grandmother blacklisted and entry to bury — exiled from her own farewell — I thought that was the worst.

When a president rearranged the world with a sentence — “Jerusalem is the capital” — I thought that was the worst.

When I could not return in November 2023 after the HSC — reward trip turned exile redux — I thought that was the worst.

I was naïve.

Every time I think we’ve reached the bottom, the earth opens.

Two hundred and fifty-five bullets into a little girl’s world – Hind Rajab – and language fails.

A friend’s grandmother trapped at a border, urgent care across a line that would not open – she died in the waiting.

Another closure, another “indefinite pause,” passports rendered ornamental – my own grandparents frozen on the wrong side of a paper gate.

And you ask me to believe in liberation?

My idea of liberation is not your glossy inspiration-porn of a brown woman “finally safe.”

Do not fold me into your TED Talk redemption arc.

My resistance is your terrorism.

My existence is your politics.

My grief is your debate topic.

My silence is still too loud.

Do you want me to shrink my anger into footnotes?

To narrow down my standards until they fit your “two-state solution”?

To be quiet, poised, elegant – احكي ‘ehki’ English so well – and keep my rage somewhere tasteful?

Because I can.

I can play the part.

I can polish my vowels, cite AGLC4 until I disappear into the margins.

But even then, when I smile politely in seminar rooms, do you see it?

How an ID card reads me louder than any accent.

How my Arabic buckles on my tongue when a ghayn غ refuses to be anglicised.

How my broken mother tongue exposes me, even when my English dazzles.

So I write.

I write and write and write until the pages pile into a small mountain of failed liberations.

A papier-mâché barricade made from drafts and scrunched endings.

A bonfire I am not allowed to light.

I type until the laptop’s memory chokes. Until the cursor blinks like a warning siren. Until my wrists ache and my jaw learns the posture of clenching.

هل

Have I freed Palestine then?

No. Of course not. But I refuse to be quiet. And refusal is a kind of survival. And survival is not small.

You want a definition? Here’s one: liberation (n.)

1. not a policy document nor a hashtag;

2. the unkillable insistence to remain;

3. the land living in your mouth even when you trip on its syllables;

4. zeht زيت glinting on a plate beside warm khubz;

5. the olive that remembers your hands;

6. the refusal to be erased – even on paper, even in footnotes.

You call that poetry. I call it breath.

Say it with me:

I am not your western porn of resilience.

I am not the tidy arc of the “good migrant girl” who “made it.”

I am not the soft-focus apology for a crime I did not commit.

I am an Arab woman. أنا امرأة عربية. and, as Rafeef taught us, we come in all shades of anger.

Where do I put that anger?

I could curl it into my palms until the crescent-shaped dents appear.

I could pour it into careful sentences and pretend they are enough.

I could swallow it until it calcifies behind my ribs.

Or I could set it on the page, slanted, let it run: not your muse not your metric not your manageable brown not your curated sorrow not your “but she’s so wellspoken”

I will not be the palatable preface to your comfort.

And still: the question keeps returning like a tide –

liberation… liberation… liberation… a word that tastes different each time it touches my tongue.

In English: strategy. timeline. reform.

In Arabic: نجاة survival. صمود sumūd. عودة return.

In my body: refusal, even when there is nothing left to refuse with.

I do not want your neat horizon. I want the right to keep imagining one.

I am told: stay elegant. Be poised. Be grateful. Be quiet.

I am told: Australia has given you a voice.

As if the voice were not already mine.

As if language itself were a visa that could be stamped and revoked.

Here is a smaller truth: sometimes liberation is a sentence that finally says what it means.

stubbornly carrying milk home anyway?

About the city teaching you to love her without promising to love you back?

I do not want to invent her to soothe myself. I want to listen.

So I’ll end this breath here and leave the margin open, a seam you can see:

Sometimes it is an untranslated word left in the middle of an English paragraph on purpose.

Sometimes it is choosing marḥaba مرحبا over hello.

Sometimes it is deciding that AGLC4 cannot footnote a wound, and writing it anyway.

I do not want to be your story’s solution.

I want to be the page you cannot turn without seeing yourself in it.

And yet, even now, I keep hearing her on the other side of the threshold.

The other me. Not theory, not trick. A life I could have lived.

I ask myself, without romance or pity:

What would she say about liberation if she were holding the pen?

Would she write about the way Arabic signs do not blur when you are not afraid of mispronouncing them?

About the old man who sells figs by Damascus Gate, the way his hands perform a daily revolution by simply counting change?

About the checkpoint you walk through like weather: dreading the storm,

If I had been there, what would I have

I turn the page.

Not the sandstone Quadrangle at Sydney Uni, its arches echoing with magpie calls and the clatter of coffee cups — but the stone steps of al-Quds , still warm from the midday sun.

Here, my end at

blocks in Ramallah. After international politics lectures, the sabaya صبايا and I claim a corner table. The air smells of cardamom coffee and faint cigarette smoke, the walls stacked with books that no one ever finishes. We spread our laptops out, pretending to study, but really just debriefing the week.

When the night gets heavy, we wander to the nearby shisha shop, clouds of smoke curling into laughter. Tarneeb طرنيب and Hand هاند cards slap against the table. Someone argues over rules, someone else orders another round of lemon–mint. By midnight we’ve migrated back to whoever’s house is closest. Mafia games, endless gossip, tea that grows stronger with every refill.

On Fridays I walk with my grandparents into the Old City for jumʿa prayers. We pass the spice stalls where Abu Bashar still leans against his counter, same as when my grandparents were young. He calls us by name, even remembers which blend of zaatar تيم they prefer. The adhan threads through the alleyways, mingling with church bells. For one suspended moment, the city itself feels like prayer.

And when the week is over, we pile into a cousin’s car for the long drive to Hebron. One hour by the straight road, four hours if you’re Palestinian. We snake through back ways, tracing olive groves and half-built walls, hoping the Israeli Occupation Force checkpoints are distracted elsewhere. Every turn carries the risk of being stopped, searched, or delayed. But eventually, we arrive — arms full of knafeh, cousins already waiting, the family circle swelling again.

Here, anger is not an essay. It doesn’t need to be disguised in polished vowels.

anger is the way Teta sprinkles mint into the pot as herbs could guard a family.

anger is Baba’s silence when the soldier waves us back.

anger is laughter stretched louder than the curfew.

anger is staying.

Even in Ramallah, the ordinary is edged with siege. We plan weekend spa trips to Carmel Hotel Bonsai Spa — massages and steam rooms — but check our phones obsessively in case the roads close. We book dinner and then text each other, هل في

Are there checkpoints? The IOF controls our calendars more than we do.

And still, tomatoes blush in the market stalls.

And still, children chase each other through narrow streets.

And still, the olive oil glows gold in the morning light.

with neighbours who call me ya ḥabibti even as sirens split the night.

Liberation here does not look like policy or treaty. It looks like Abu Bashar opening his shop every Friday morning. It looks like cousins gathered even after four hours of detours. It looks like a child blowing smoke rings with her uncle’s shisha hose and laughing so hard she forgets the blackout.

ache is already proof. Do you not know that? Even the stutter of ghayn is a kind of resistance. The word insists on being said, even in your foreign mouth. We both carry the same exile. Only yours

palate.

refusing to call occupation anything but occupation.

Liberation here is not a promise deferred –

it is a child who still laughs in Arabic.

I write until my wrists ache, until every margin is swollen with ink, and still Palestine remains chained. I tell myself that words matter — that law review essays and protest chants and footnotes in AGLC4 can be a form of resistance. And yet, when the cursor blinks back at me, mocking, I wonder if writing is nothing more than building barricades out of paper.

You think writing is a barricade?

Here, in Ramallah, I free Palestine by waking up tomorrow. By walking to SUFI صوفي and studying until midnight with the sabaya. By buying figs from Abu Bashar’s stall though I know a soldier could flip the crates at any moment. By driving three hours of backroads to Hebron, refusing to let a checkpoint decide who I see, who I love.

This is not romance. The occupation is still the air in my lungs. But when I exhale, it is not an apology: it is صمود sumūd, steadfastness.

The other Jaseena — you, Sydney Jaseena — writes of classrooms where flags are banned, of broken Arabic. I write of curfews and detours, soldiers and spice vendors. Both cages, both humiliations, but shaped differently. Mine comes with the taste of zaatar,

But here in Sydney, my checkpoints are invisible. They sit in classrooms where flags are banned, in jobs where saying “Palestine” is too political, in conversations where silence is survival. I mispronounce , trip over broken Arabic, watch my heritage slip between my teeth. I

Maybe that’s why I keep writing.. To shout in ink what I cannot in lecture halls. To carry anger that otherwise calcifies behind my ribs. To prove I exist

And I do not ask where to put my anger. I plant it. In zaatar pies, in laughter that outruns curfews, in the mint Teta stirs into tea as though herbs could keep us safe. My anger is not an essay, it is the soil under my nails.

Then tell me — is liberation possible at all? Or are we both only circling the same impossibility from different geographies?

Liberation is not possible. Liberation is necessary. Here, it is the child who still laughs in Arabic. There, it is you refusing to swallow the word Palestine even when it makes your accent burn. Both are survival. Both are freedom’s rehearsal.

And I realise, for the first time, that we are not two voices trading definitions. We are the same wound, split across continents. We are the same insistence, written twice.

You want me to define liberation, pin it down, fit it into your treaty-sized box.

but my Liberation will not wear your western grammar.

Liberation does not shrink to the margins of your committee notes.

Liberation is not a hashtag, not a ceasefire “paused until further notice.”

do you want me to be poised? I will not.

do you want me to be grateful? I will not.

do you want me to be quiet? I will not.

I am not your inspiration porn.

I am not the migrant girl who “made it.”

I am not the elegy you can skim before moving on.

I am an Arab woman,

and we come in all shades of anger. so hear me:

my Liberation is not your compromise. not your two-state figment. not your Oslo déjà vu. not your technocratic illusion of “peace.” my Liberation is return.

my Liberation is sumūd صمود –steadfastness – until the word itself grows roots.

my Liberation is refusal – even when there is nothing left to refuse with. my Liberation is survival – unpalatable, untranslatable, unkillable.

and if that frightens you, good. if that unsettles you, better. if that makes you turn the page and cannot stop thinking about it – then maybe, finally, you’ve tasted it.

the scream lodged in my grandmother’s throat when they blacklisted her from burying her sister.

the checkpoint that turns an hour’s drive to Hebron into four hours of humiliation. the child’s laughter that still breaks curfew.

the word فلسطين written slanted across my lecture notes, daring the professor to notice.

because I will not write a polite ending. I will not leave you with resolution. I will leave you with this:

Liberation is refusing to make my anger pretty. refusing to cut my tongue to fit your

Palestine will be free not because you allow it, not because you signed it, but because we insist on breathing. that is Liberation.

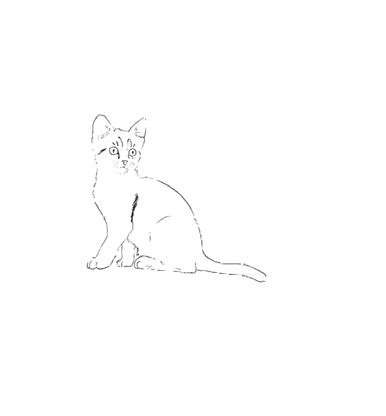

Art by Purny Ahmed

Imogen

Sabey

The Opening Ceremony of the Student Journalism Conference was surreal. I was bumbling with nerves, and also working really hard to memorise everyone’s names (which a friend from Farrago tells me was successful) whilst watching most of the student publications in Australia stream in the door.

Firstly, Victor Zhang gave an Acknowledgement of Country, speaking about the Gadigal land that everyone had travelled to and the importance of First Nations sovereignty. Next, I gave a welcoming speech, highlighting the landmark moment of having so many publications in the same room and how rare it was for such a thing to happen. It was a privilege to be able to speak directly to so many people, and to see them interacting with each other. One of the most rewarding aspects is seeing how my work in bringing people together has fostered an environment where student publications who otherwise wouldn’t have known each other can work together to build and improve their media.

Then we had a presentation from all of the publications in attendance. First up was

Grapeshot, the Macquarie Uni magazine, presented by the fabulous deputy editorin-chief Kayleigh Grieg. That was followed by Noise (UNSW) SURG (USyd), RadMon (Monash), Lot’s Wife (also Monash), Woroni (ANU), Farrago (UniMelb) and many others.

One of the highlights was hearing from Amanda Palmera, Meijie Ureta and Michael Hamza Mustapha from The LaSallian, the student newspaper/magazine at the De La Salle University in Manila. It was the first time an international student publication had been hosted in Australia, so that was a terrific learning experience for the Australian media, and proved instrumental later on in the conference when we were discussing the creation of the Student Media Association.

After all the presentations were over, we hosted a quiz — because everyone loves Kahoot — and there was a frenetic scramble for phones as everyone raced to join in. The questions varied wildly, from the oldest publication in the state, the correct sauce to put on a halal snack pack, and my favourite biscuit (the answer is the raisin & oat ones I make at home). There was a bit of chaos when people disagreed on some of the answers, but ultimately Joey Mann (Woroni) came first.

And with that, StuJoCon kicked off with a bang.

Gabrielle Tan

One of the first events was Eda Gunaydin’s Q&A, a deep exploration of writing, voice, and belonging, drawing on her remarkable career as an author, essayist and lecturer.

Prompted by insightful questions from Mehnaaz Hossain, Gunaydin brought her audience into the process of crafting an essay and finding yourself within your writing. Her advice for the room of young writers before her was to not be afraid of “working something out as you write”, and to allow yourself to be critical and see the subjects of your essays reflected in the real world.

The 2025 Student Journalism Conference, hosted by Honi Soit, was the biggest event of the year for student media and also the biggest student media gathering to date. Here are the highlights as reviewed by our reporters at Honi, some of the editors, and student journalists across the country.

Valiantly pushing through a mild cold, Gunaydin answered questions from Hossain and the audience with deep, sweeping insights into navigating trauma, guilt and love in family life and how themes like class mobility have affected not only her writing but the way she sees the world. She talked about transforming personal writing into public writing, as she did in her 2022 book Root and Branch, and explored the ever-changing cultural and artistic face of Western Sydney.

From topics like kebab shops, the inherent femininity of personal narratives, art on the fringes and her own experiences from her time at USyd, Gunaydin’s inquisitively reflective answers allowed her audience to think of their own backgrounds and how they influence their own writing.

issues facing student radio. At its heart, radio has always been about music. Throughout the speaking segments, local music from Sydney and Melbourne blasted the airwaves. Discussions surrounding the difficulties of making it in the local scenes were a common bonding experience for student artists across both stations. It was highlighted that whilst student radio doesn’t have the same reach as Triple J, it provides a vital starting point that many student artists need to build community and get their music out there.

As the conversation progressed, the issues and logistical problems of running a radio station became very apparent. From limited budgets, licensing fees and technical problems, both RadMon and SURG shared similar hardships when it came to running their own stations. Other students in the room; who were interested in starting up their own stations, voiced similar difficulties. The technical challenges of broadcasting were something every radio person felt in the room, and it was clearly a large issue to many stations.

Georgie McColm (Radio Monash)

What happens when you get the two oldest student radio stations in Australia together in a basement at the Student Journalism Conference? A broadcast 50 years in the making. RadMon and SURG got behind the mics to break down DIY student radio. In a small underground studio, students and radioheads alike listened to a live broadcast of the current

With the rise of Spotify and streaming, radio has been labelled as a dying art form. However, the panellists had a more positive outlook. The common sentiment was that whilst radio had changed, but is by no means dying, just evolving into another medium. If there is one thing everyone took away from this workshop, it’s that student radio is thriving. There are certainly difficulties, but the passion in that room has never been stronger.

Cheng Lei

Sath Balasuriya

The first day of StuJoCon featured an interview with Cheng Lei, a reporter and news anchor for the China Global Television Network who was spuriously detained in 2020 by the Chinese state.

The interview revolved around her life in prison and the day to day anguish that accompanied her three-year stint in detention. Lei’s story was both captivating and earnest. At one point, she described how sorely she missed out on three years of her young children’s lives during her detention. It was evident that Lei attributed much of her resilience throughout her sentence to the persistent diplomatic efforts led by her family in Australia. She encouraged student journalists to start building a strong support system that they could rely on if they fell in the line of fire.

While Lei rightfully attributed much of her bravery during this period to her family, she also emphasised the internal resilience that she found within herself during detention, and the unconventional means that she turned to do so.

Victor Zhang

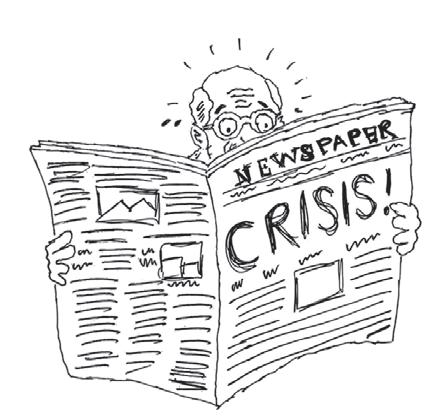

I must admit that when I took upon the task of moderating this panel, I was quite nervous. Antony Loewenstein, author of the Walkley award-winning book The Palestine Laboratory and co-founder of investigative reporting platform Declassified Australia, and Wendy Bacon, investigative journalist, activist, and professor known for her fearless reporting on social and climate justice, both had a wealth of wisdom and experience to share. Really, one-and-aquarter hours just wasn’t enough time to pick their brains.

A particular question on my mind that had myself and many others ill at ease was regarding the place of young and upcoming journalists in a media landscape that is increasingly asking us to compromise our values (“definitely don’t compromise on your morals” said Lowenstein).

On the topic of “activist” being used as a pejorative against journalists, Loewenstein reminded us that most journalists who work for “corporate media are actually deeply activist-minded, but it’s activist in the service of power.”

I am reminded here of Bacon’s description of her work, where she views her journalism as something that should be “useful to those who resist abuses of power and seek social justice rather than supporting existing power structures”.

Kiah Nanavati

Investigative journalism is often romanticised as the noble pursuit of truth, but listening to Kate McClymont unpack her career reveals it as something far sharper: a world of constant threat, endless patience, unrelenting persistence and most of all, confidence in oneself.

McClymont’s panel painted a portrait of a journalist unafraid to step into murky waters. Her exposé on Michael Wilson, the national president of the Australian Order of Paramedics, remains one of her defining moments. Through painstaking research and tip-offs, she uncovered his theft of $20 million from hospitals. Though Wilson pleaded guilty, he walked free, a grim reminder of the political system’s failures. For her, the work is less about justice in courtrooms and more about relentlessly holding power to account. That’s the entire point of being a journalist in the investigative field.

The methods she described are as varied as the stories she chases. Sometimes charm and politeness secure a source; other times, grilling is necessary. She recounted tales of degree fraudsters, scams, and the torrent of online abuse hurled her way. Death threats came too — but McClymont never flinched. Instead, she quipped: “If they wanted to kill you, they would. The ones that threaten you aren’t the ones to worry about.”

Georgie McColm (Radio Monash)

Hosted by Honi Soit’s Charlotte Saker, the guest speakers of this radio panel included Joel Werner, a current ABC executive producer, who’s worked on Science Vs, The Sum Of All Parts and Freakonomics. He has an extensive history in science journalism, and has produced content both domestically and internationally. The second panellist Kwame Slusher is currently a producer of the show All The Best at FBi Radio. In addition, he’s also undertaking studies at the Australian Film Television and Radio School.

The first thing that stood out about these panellists, is their backgrounds in community radio. Both Kwame and Joel have tertiary training as media creators, but both acknowledged their skills sets came to life after working at community radio stations. For Kwame, he started producing at FBi Radio. As for Joel, after he finished his science degree in psychology, he began volunteering at 2SER, an education based community station.

Joel mentioned that “community radio is the most important thing. It’s great to study at universities, but the best way to become a great audio maker, is to be a part of a community station.”

Kwame described community radio as “a safe space to make and create.”

For Lei, her imagination offered her a quaint yet substantial reprieve from her journalistic senses that could only detect despair where they looked. She told us how she found herself in a childlike state, making up skits between imaginary characters to keep her entertained.

In closing, Lei answered questions on the China-US relationship and where the relationship might head with Trump’s recent antagonism towards China. Lei dissuaded the anxiety in the room with her answer that there likely wouldn’t be any direct fighting between the two superpowers anytime soon. As Lei saw it, both China and the US had become accustomed to the positions they had each carved themselves in the global hierarchy, and saw little reason to topple their relationship as a result.

Referring to the role of independent media such as Loewenstein and Peter Cronau’s Declassified Australia — which has exposed Australia’s role in arming Israel’s genocide in Palestine — Bacon makes the point that “often the most meticulous journalism is done by the people who are called ‘activist’ journalists”.

We spoke at length about the decline in, and failure of, much of the legacy media landscape. Despite this, Loewenstein worries that “there is nothing yet to majorly replace” well-resourced legacy media outlets which can provide the resources necessary for robust journalism.

Despite much of our conversation being centred on the grim crisis in the media landscape, we were left with a hope that there could be, or rather there needs be, journalists that could do the right thing. Bacon ended the session with a powerful call to action, that “the need for journalism, the need for information presented in ways that is digestible for people and relates to their lives, could not be more important than it is now”.

One of the most riveting stories she shared involved a man who was photographed with a group of associates… only to later be murdered by those very same men. McClymont, suspecting foul play, staked out the unfolding drama herself, disguised as a dog walker. Her instincts proved right: police had also received a tip-off and were ready, eventually arresting a man who tried to flee. It was a stark reminder that danger isn’t abstract in her field; it is lived and immediate despite the stake being really high.

From Sydney boardrooms to whispers as far away as Arkansas, McClymont insists stories are everywhere. What matters, she told the audience, is persistence: “Just keep going.” It was a conclusion that summed up both her career and her advice “journalism may be fraught with danger, but it is sustained by courage, wit, and the dogged refusal to back down.”

The question of radio’s viability was brought forth towards the latter half of the panel.

Joel answered the question with what a common sentiment in radio, “everyone is thinking about this at the moment, what the right balance is.” He remarks that podcasts are just an evolution radio.

In addressing this audience question, Kwame hammered home the importance of knowing your audience. Who are they? When do they listen? How do they listen? What’s keeping them listening? He suggested to “sit down and create an avatar of your audience,” and fully conceptualise your listeners through statistics to guide your creation.

Both creators acknowledge the issues of radio in a digital and DAB+ world, but are hopeful for the medium evolving instead of dying.

At RadMon, we echo this train of thought. Radio will never be what it once was, but it has already evolved. Kwame’s own experiences in connecting with the audience rings true, even at student stations. The listenership comes from building a relationship with the audience. That’s how radio, whether it’s live or prerecorded stays alive.

This is an extract of a review published on RadMon’s website. Read in full online.

Eryn Yates (Vertigo, UTS)

One of the panels I attended was led by Tracy Holmes, an ABC radio presenter with an extensive career in television and radio. Holmes’s specialty is sport, and her resume is impressive. She has worked as a sports presenter for Channel 7, co-hosted the 1998 FIFA World Cup, and presented in Hong Kong and Beijing. She was the first woman to host a national sports program, Grandstand, and reported for the ABC at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics.

Despite all of this, at first, I wasn’t exactly rushing to Holmes’ panel. Sports journalism has never been an area of interest, and I half-expected to be checking my phone the whole time. However, within the first 15 minutes, Holmes fundamentally reframed my conventional understanding of sports journalism. She said that her journalistic interest does not lie in who wins or loses, nor in the injuries that may occur, but rather in the strategic engagement that sport demands. That sport is not a separate sphere but a lens through which broader social, cultural, and political phenomena can be observed. Every match, press conference, and even minor victory or defeat offers insight into societal dynamics, provided one examines it with sufficient critical attention.

For student journalists, her guidance was incredibly instructive. Using the Olympics as an example, Holmes showed that these events are about far more than athletic performance. The media often outnumbers the athletes themselves, and the stories it tells shape how the world sees nations and identities. Sport can act as a microcosm of society, revealing issues of inequality, activism, gender politics, and diplomacy. Yet in Australia, much of the coverage glosses over these layers, missing a huge opportunity to use sport as a lens for critical and socially aware storytelling. She emphasised the importance of foregrounding human narratives and allowing audiences to engage interpretively rather than prescribing conclusions.

By the conclusion of the panel, I felt…

inspired. Holmes did more than outline the practice of sports journalism. She reinforced that in every field, the media has power, and the way we choose to wield that power shapes how the world perceives it.

Ethan Floyd (2023 Honi editor)

The zine-making workshop, run by Bipasha Chakraborty (former editor of PULP Magazine and Honi Soit) and current Honi editor Ellie Robertson, was one of the more hands-on sessions of the conference. While I was the only other former student journalist in the room, the rest of the crowd was a mix of current editors and contributors from around the continent looking to add another tool to their student media arsenal.

The focus was firmly on practice over theory: how to fold a template and arrange scraps of text and images into a self-contained publication. One participant ran with a pretty novel idea, sketching portraits of everyone in the room and assembling them into a zine by the end — proof of how quickly the form lends itself to personal expression and experimentation.

Law has since become a screen-writer, radio host, playwright, author and even previous Survivor contestant, refusing to chain himself to one thing. Interviewed by Honi Soit’s William Winter, Law responded to questions such as how he viewed Sydney’s theatre scene with quips such as “You know how hot people don’t have to develop a personality? That’s like Sydney.” Alongside his lighthearted banter, Law also delivered plenty of wisdom, reminding us that memoir is not exposé, and stressing the need to actually consider the consequences when it comes to writing about loved ones. “Write with the door closed and edit with the door open,” he says, underlining that the writing process doesn’t end at selfindulgence; it needs to be modified for the audience. In the making of his family biography

What was missing, though, was much of a sense of the radical history behind zine publishing. A little more time spent on this “why” would have given the session a lot more weight.

Still, there was something liberating in the reminder that publishing can be so tactual, in folding, stapling, and photocopying. Running a student paper today is almost an entirely digitised ritual: gone are the days of typewriter and letterpress, of paste-up and bromide camera. Now, we huddle over InDesign into the early hours, wrestle with WordPress plugins, and pray to the algorithm that our words reach students who wouldn’t otherwise recognise the name Honi Soit

Against that backdrop, the workshop offered a glimpse of publishing stripped back to its most elemental form: paper, scissors, glue, and the thrill of making something with your hands.

Kayleigh Grieg (Grapeshot, Macquarie Univerity)

Charismatic and intriguingly multitalented, Benjamin Law proved to be one of the most entertaining guests of the conference, and a model example of what a prior stujo can become. From humble beginnings as an editor of QUT’s previous publication Utopia,

The Family Law, he allowed all members months to read the manuscript before it was published. Though comical and wild, Law assured us that his biography was entirely true, as proven by the documentary version in which his family is just as “lovably unhinged” as he portrayed them. Expressing a fascination with social taboos through his work, Law continues to tell stories about growing up queer and Asian in Australia, religion, death, sex, money, hoarding disorder and more through any medium he can master.

I was excited at the opportunity to hear Benjamin Law as a guest speaker for the Student Journalism Conference (great job guys!) at USyd. It was cold and rainy, but none of that mattered when I was warmly greeted by the interviewer for that session, Will Winter.

We came across Benjamin at the entrance. You could see Will was nervous but kept his composure and was very professional. Benjamin was warm and friendly; I went to chat with him until the interview began.

As the interview began, Benjamin embraced the inquisitiveness of the young man sitting across from him, each question answered with enthusiasm and honesty. His talent for storytelling brought his stories to life, captivating his young and keen audience (and me). He shared personal tales, his journey, and what’s ahead for him.

When it came to question

time, Benjamin gave each participant his undivided attention, uniquely answering each one.

It was just over two hours when it concluded, and Benjamin still stopped to chat with fans on his way out.

Before he disappeared into the rain, he thanked Will and gave him a warm hug. I also got a warm hug… those are the perks of being the proud mum of Will Winter.

After a raucous welcome party at The Rose the night prior, conference attendees found themselves on Saturday in discussion with Jacqueline Maley, senior writer and columnist at the Sydney Morning Herald (SMH) and The Age.

The interview began with Maley discussing the journalistic practices intrinsic to her work and the difficulties she navigated in modifying those practices after her recent foray into fiction writing. Journalistic writing develops “fast twitch fibers” according to Maley: editorial decisions must be made quickly, leads must be tracked down before they disappear, and huge amounts of research must be sifted through at lightning speed to find relevant information.

When she was writing her latest novel, Lonely Mouth, Maley admitted that she found herself unable to write fiction and write for the SMH during the same day. She stressed the need for compartmentalisation for effective journalism, and for journalists to take account of the unique constraints placed upon them to do their best work.

Maley also discussed similarities between her writing across newspapers and novels alike. A highlight was Maley explaining the interest that she had in uncovering gender-based injustice across her work, whether in her investigation alleging sexual misconduct against a former High Court judge or Lonely Mouth.

She also brought up plenty of practical advice for budding journalists. Jacqueline’s closing remark for eager stujos was especially memorable: don’t be afraid to call leads on the phone.

Riley Bampton (Glass, QUT)

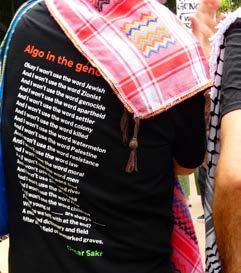

Omar Sakr is an Australian poet, born in Western Sydney. He has been a published poet since 2014 with over 80 of his poems appearing in various literary journals and magazines. Since Sakr began writing, he has published five poetry collections, with his most recentbeing The Nightmare Sequence, a collaborative work between himself and visual artist Safdar Ahmed. Safdar Ahmed is an award-winning writer, musician, visual artist, andcreative based in Sydney.

Ahmed has published three books and is best known for his 2021 graphic novel, Still Alive.

The Nightmare Sequence was my introduction to both Sakr and Ahmed’s work. The book is a harrowing response to the genocide committed by the state of Israel in Gaza beyond October 2023. At this year’s StuJoCon, I had the privilege of attending a talk from both creatives called Art & Activism.

I will not describe the panel as enjoyable, because it was not meant to be. The topics discussed were around the ongoing genocide in Gaza. I went into the talk excited to hearfrom two astounding creatives and was immediately faced with the reality of its content. Iwas confronted by my own complicity.

During the talk, Omar Sakr spoke on how he writes about violence without aestheticising it. Sakr explained that in most cases violence morphs into a form of content and that many ofthe poems in The Nightmare Sequence were written as a response to this. “These poemsare about capturing a sense of what we are witnessing in the 2nd or 3rd degree. We are, at best, witnessing the witness.”

Safdar Ahmed was asked how exactly he decides what to show with his illustrations. He replied saying that he wanted to highlight everything that our media is ignoring. Ahmed believes that mainstream media reporting does not go far enough, and, in some cases,deliberately omits certain facts.

For me, this panel was the most important events I attended at StuJoCon. It has actively changed the way I look at and engage with the world.

I’ll finish this review with a quote from Omar that has stayed with me, “The reality of this genocide is totally and completely overwhelming.

“When you do recognise it then you have to face your role and the violence that upholds the comfort in your life”.

You can buy The Nightmare Sequence directly from the publisher, UQP. All artist royalties go to supporting aid in Gaza.

Kiah Nanavati

The panel on student journalism offered a compelling glimpse into the passion, risks, and responsibilities that come with reporting from the margins. Speakers Mathilda Stewart, Bianca Nogrady, and Pam Walker reminded the audience that these publications have always been more than training grounds—they are spaces of defiance. As Bianca and Pam stressed, campus reporters capture activism and protest in ways mainstream outlets cannot, because they live the stories alongside their peers. “Curiosity

Jessica Louise Smith

Though known for his involvement in the comedy group The Chaser, Dominic Knight, novelist and part-time academic at USyd, traces his path to becoming a professional comedian back to his days of student journalism.

Knight candidly recalls a seven-year-old Dominic making magazines with texta and naming them after himself — he didn’t reveal these names, but I’d hedge my bets on Domination or Knight Nightly — but his journey as a writer really began for him around Year 9, editing his high

and enthusiasm make journalism,” Pam remarked.

The panelists highlighted the freedoms and constraints of this work. From provocative student newspapers in the 1990s to Pam’s stories of taking on corrupt developers, politicians or really heinous playwrights, the anecdotes revealed how courage can outweigh caution. Yet threats to student journalism remain familiar: limited funding, censorship, and institutional pressure.

“Don’t be afraid of weapons that silence you,” Bianca advised, while Imogen’s rallying cry — “keep fighting and no rest” — drew nods from the crowd.

Science journalism also found its place in the conversation, with Bianca delighting in the endless questions of climate, biodiversity, and pandemics. But debates over objectivity sparked the fiercest exchange. Pam insisted on balance, giving all sides a voice, while Mathilda argued that perspectives denying climate change or upholding white supremacy do not deserve oxygen. Bianca, caught in the middle, admitted “balance is hard.”

What unified the panel was the belief that student journalism is essential because it is fiery, loud, and unapologetically political. It amplifies voices often silenced elsewhere, while testing the edges of freedom of speech. As Pam concluded, “Journalists have power, and with power comes responsibility”, a reminder that student journalists are not just reporting the future of media but shaping it.

school magazine. From there, he caught the journalism bug, going on to edit the, now non-existent, Union Recorder, and then our beloved Honi Soit.

“Trying to second-guess audience reactions is a recipe for mediocrity.”

He reminisced on stupol memories, strongly discouraging us to read his novel on said topic — see Everything and Nothing Changes: Reflections on Dom Knight’s ‘Comrades’, a 2021 review by Grace Lagan, for context. Like many an Honi editor, Knight honed his comedy skills back in the day by poking fun at the ironic and dichotomy of USyd’s student politics, leaving the audience with the timeless sentiment: “(Stupol) does matter, but that doesn’t mean it’s not funny”.

Thank you to Joey Mann from ANU’s Woroni for moderating this session, and thank you, of course, to Dominic Knight for introducing a new generation to the iconic 2007 APEC Summit stunt. We are feeling inspired — big things to come in the Honi Soit comedy section!

Alana Valentine

Gracie Hosie (Glass, QUT)

Whoever told you not to meet your heroes is lying. When Alana Valentine sat before us, it felt less like a keynote and more like a masterclass in the moral responsibilities of storytelling. As a personal fan who has long looked towards her work for inspiration, I found her session both grounding and deeply moving, a reminder of why voices like hers are vital in Australian arts and journalism alike.

Valentine, a celebrated playwright and icon, is known for her compelling and compassionate approach to verbatim theatre. She spoke candidly about how she gathers stories through interviews, testimonies, and archives, transforming real experiences into dramatic works that demand empathy and accountability. Hearing her unpack that process in real time, the ethical tightrope of truth, permission, and representation, was an invaluable insight for any writer or journalist trying to tell human stories with integrity.

What struck me most was how she drew parallels between journalism and theatre. Both acts of bearing witness, both art forms that rely on credibility, and both forms capable of shifting public consciousness. She challenged the room of student journalists to think critically about their own role as storytellers, asking us to consider not just what we publish, but why and for whom.

After discussing the many highs and lows of his career, Knight blessed us with a little tidbit on how to prevent being ‘cancelled’, “the politics of your comedy should be defensible” — a message that should be widely distributed to teenage boys on the r/darkhumour subreddit.

“The key skill is having the humility to get better.”

Valentine referenced several of her most acclaimed works, including Parramatta Girls, Letters to Lindy, and Wayside Bride. Each example illustrated her ongoing commitment to community collaboration and truth-telling, art that listens before it speaks. Her anecdotes about navigating resistance and earning trust from participants revealed just how much patience and care underpin her creative success.

As someone who has admired her writing for years, seeing Valentine in conversation reaffirmed her reputation as one of Australia’s most ethically grounded and emotionally intelligent storytellers. Her presence at StuJoCon was more than a talk, it was an inspiration for all emerging writers and artists to create with compassion and courage in storytelling.

The hard part of student media, though, is pointing out the depravity of individuals or institutions and to advocate for the wronged.

as a political enemy, it can be viewed as a public relations tool instead, which is honestly just as difficult to live with.

After all, student media do not write about and for themselves, but for the people whose stories need to be written.

Art by Charlotte Saker

Student journalists stand as the chroniclers of university life, storytellers that shine the spotlight on minorities, and conversationalists who ensure that the student body are not only aware but also critical of the narratives that swirl around campus walls. The hard part of student media, though, is pointing out the depravity of individuals or institutions and to advocate for the wronged. This can carry severe consequences, not just for the journalists in the moment, but for the student body down the line.

Student media have long fought to combat all forms of corruption by uncloaking them to enforce accountability and justice. But because corruption repels what is correct, campus journalists face looming threats from administrations for their service of reportage.

In the Philippines, 1,000 cases of campus press freedom violations, 206 in 2024 alone, have been recorded by the College Editors Guild of the Philippines, the Philippines’ national union of student publications. These violations encompass censorship, state surveillance, and budget freezes, among others. And in general, the country ranked 116th in the latest Press Freedom Index (PFI) by Reporters Without Borders.

For Australia, while faring higher in the PFI at 29th place, various campus publications still face looming threats of censorship and budget cuts from their administrations or unions. Not only that, there is no baseline legal protection for Australian student media, compared to the Philippines’ Campus Journalism Act of 1991 (CJA). The CJA was ratified after the Marcos Sr. dictatorship (Martial Law), which clamped Filipino media outlets and targeted Filipino journalists, to recognize the role of student media in sparking discussions and movements among the youth against repression. With this, student media being safeguarded by law is utmost essential.

Censorship is already a tell-tale sign of avoiding accountability for misdeeds. It means attempts to forget history, such as political censorship against campus publications in Cagayan State University for their reportage of the 53rd commemoration of Martial Law’s declaration last September. At the social level, it also means subjecting to conformity, such as taping black bars on Honi Soit’s notorious “Vagi Soit” edition as consenting women’s genitalia seemed to be too explicit for adult eyes.

In my experience as a former

Meijie Ureta sends courage from the Philippines.

Managing Editor of The LaSallian, the official student publication of De La Salle University, I admit that we have protection against political forces and rough attacks. Still, we got jabs from our school administration, fellow student organisations, and external groups for our reporting.

I remember receiving an email last year wherein a large fast fashion brand requested us to take down our report of their tent falling over along a major walkway in our campus, as they feared for their “publicity.” Similar requests persisted throughout my tenure and even after. Recently, the publication was told by the administration and the student government to take down a report of a security threat directed at our university on 2nd October to not cause “mass hysteria.”

We had a justifiable reason to refuse in both cases: our service of delivering information to the student body. However, recalling them made me realise how much the social factor can affect our work and how others interpret it. If the press is not seen as a political enemy, it can be viewed as a public relations tool instead, which is honestly just as difficult to live with as fellow students could also push that narrative.

I could talk all day about the dilemmas student media have had to withstand, but what must be discussed is the repercussions these have on the student population. Circling back to corruption, its tendency to hide the truth is an unfortunate regularity, especially when not complemented by genuine accountability. For as long as these silencing tactics continue, we may be prone to feeling unfazed by the problems plaguing our communities. Moreso, because we are desensitised by deceit, we may not question wrongdoings.

We may also not decipher what is right, wrong, or nuanced because truth and fake news are starting to blur together in the current information landscape. This is exacerbated by concerning literacy rates, wherein the Philippines only has 70.8 per cent functional literacy (literacy skills that go beyond basic levels) according to the Philippine Statistics Authority, and Australia showing 97 per cent insufficient media literacy based on the Public Interest Journalism Initiative.

In this digital age, we have also become more prone to knee-jerk reactions as our ability to analyse carefully and respectfully becomes undermined. Academic literature showsthat critical thinking definitely accounts

for acknowledging the limits of our knowledge as well as our personal biases, which is especially important given our tendency to source our information from social media. This information can be accessible without proper regulations, and our swelled irrationality can become bigotry simply because of the mere existence of freedom of speech.

With this, while the student body is not directly affected by the distress of censorship tactics, the subtle change in how they can receive, process, and discuss information can start to affect the social climate of their campus and beyond.

Despite everything, student media continue to press forward. Yet this is a long, steep trek considering the overall circumstances of not only respective institutions but society at large. While the Philippines has the CJA, it is relatively fragile given the lack of provisions for digital media, defense against school interference, and penalties for violators. Filipino student media are lobbying for the Campus Press Freedom Bill in response to this, but it unfortunately remains in legal limbo for the past 13 years as it was constantly met with no progress in the Philippine Congress.

For Australia, the Student Media Association (SMA) was recently established as the country’s first campus media union after finding inspiration from the courage of Filipino student media. The SMA aims to become an agent to solidify protection and advocacies for Australian student journalism, and that one day they too could have legal protection in their national governance.

As student media continues to be under siege, its protection and defense means more than ever. This means more than keeping these publications running; the general student population deserve and must receive news and practice discourse of what is happening inside of their campuses, because they will carry it outside when dealing with larger societal issues. If the rights of student media are protected, then the rights of the student body are protected as well.

After all, student media do not write about and for themselves, but for the people whose stories need to be written in order to be honored, advocated, and remembered. This fight must stretch beyond perseverance if the end goal is to deliver accountability and justice.

Kira Kwong is stopping the self-fulfilling prophecy.