LE PANIER FILM ARCHIVE

THESIS DESIGN REPORT

DANIEL SMITH

STAGE 5 2023/24

MACKINTOSH SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

SYNOPSIS

ACT ONE (CONTEXT)

INTRODUCTION

CONTEXT OF MARSEILLE

MARSEILLE AND HISTORY

PORT ANTIQUE

CONTEXT OF LE PANIER

IMAGES IN THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

L A VOIE HISTORIQUE

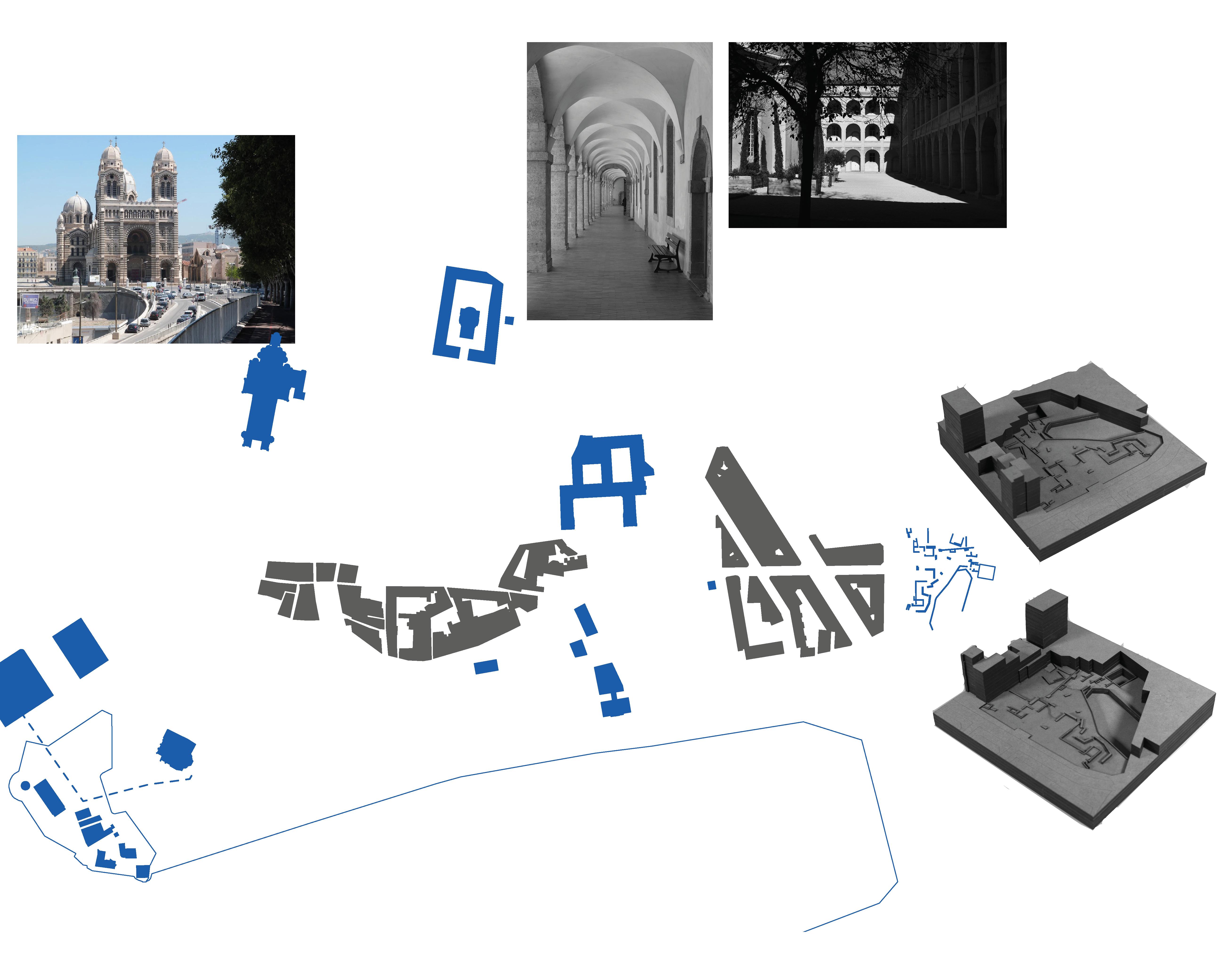

MORPHOLOGICAL EVOLUTION OF MARSEILLE

LE PANIER AS PALIMPSEST OF HISTORICAL LAYERS

FILMIC LE PANIER

MARSEILLE IN FILM

ACT TWO (METHOD)

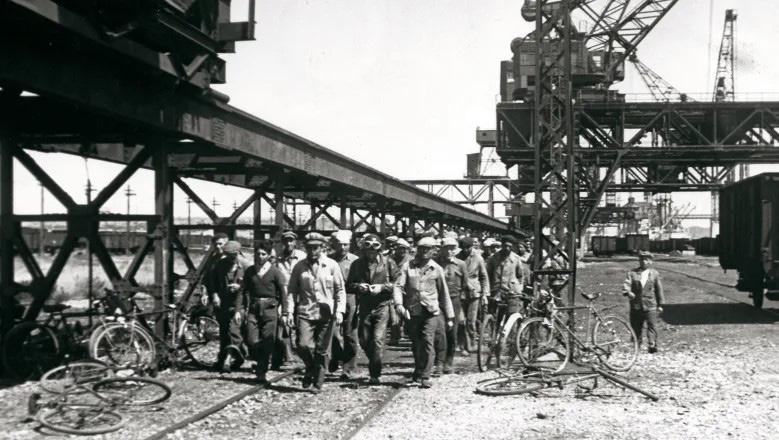

PAUL CARPITA AND NEOREALIST FILM IN MARSEILLE

PL ACE DES MOULINS

MARSEILLE’S CISTERNS

MARSEILLE’S 2 HISTORIES

MARSEILLE CINEMATHEQUE

ARCHITECTURAL DRIVERS

DEVELOPMENT OF THE KEY CONCEPT

DEVELOPMENT OF THE CINEMATIC LINK

ACT THREE (RESOLUTION)

FINAL EXHIBITION BOARD

CONCLUSIONS

REFLECTIONS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

SYNOPSIS

Thesis Titlle:

(HI)STORIES: PROJECTIONS OF MARSEILLE IN FILM AND THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

The thesis’ chosen territory is Le Panier, a historic and contested part of Marseille. Le Panier is a palimpsest of urban renewals which have manipulated the urban fabric to express desired identities of Marseille. Within this territory, the thesis explores two histories of Marseille: its history of film, and the remaining artefacts of the 19th century water cisterns.

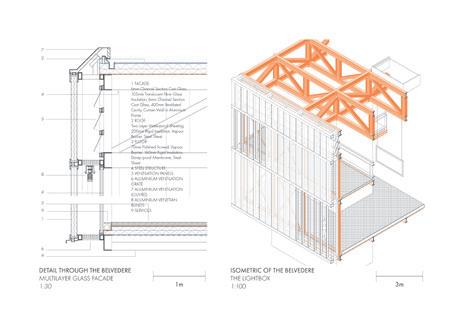

Film is used as a means of re-conceiving Le Panier’s identity within Marseille by uncovering the hidden artefact of the cistern and the establishment of a belvedere above Le Panier as a means of projecting a new image of Marseille.

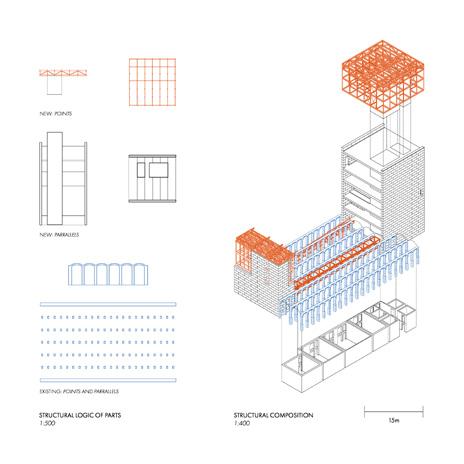

The proposal focuses on a programme of a cinematheque focused on Marseillais director Paul Carpita and this hidden lineage of Marseillais working class film. The proposal focuses on the construction of a cinematic journey which links the now uncovered cistern and the created belvedere of the lightbox. The tectonic strategy focuses on the construction of a lightbox atop a historic base. Two elements which are bisected by an elevated plaza.

Overall, the thesis aims to speculate on how images, historical and fictional, can be used to project identities of the city, and how a more ethical dialogue between the historic and the new can be facilitated through the projection of images.

Key words: Le Panier, film, cinematheque, images of the city, historic fabric.

INTRODUCTION

The thesis report aims to layout the research which forms the foundation of the thesis. Split into the 3 Acts the report aims to explore the understanding of Marseille, Le Panier, and the site which has been informed by reading, surveys, and visits. The report will then explore how this contextual background is translated into key urban and architectural strategies and look at iterations developed in response to these strategies. The report concludes by setting out the final responses presented in the final thesis submission and the final architectural technology submission.

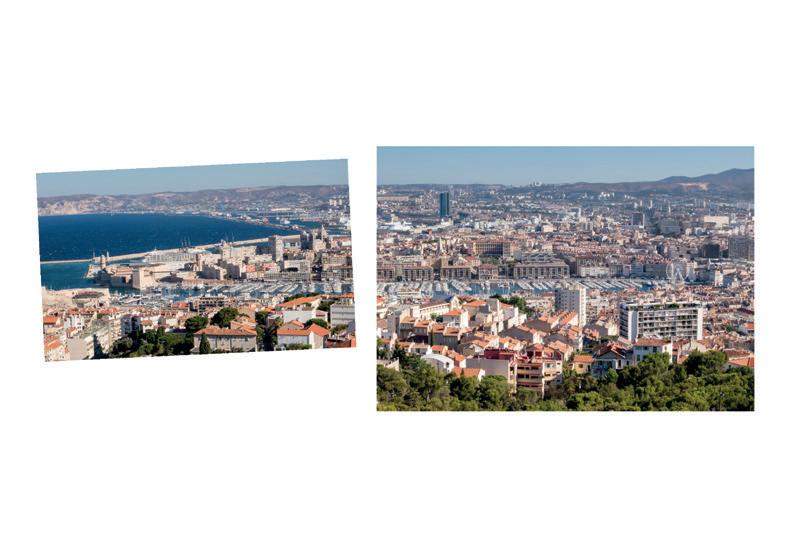

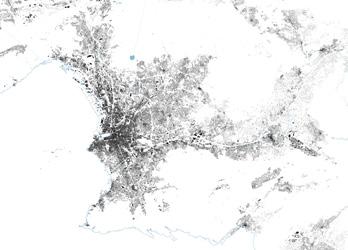

CONTEXT OF MARSEILLE

Marseille is made up of a range of perceived identities: as historically Mediterranean, as antagonistically anti-French, as a den of criminality, as an industrial working-class city, as a city of immigrants, as a leisure destination for those from the north. It is this layered identity, part fiction and part truth that make up the contradictory image of Marseille.

The book, Marseille Mix by William Firebrace describes these contradictions in some detail. Similar to Marseille’s image, the book is part fiction and part truth, describing the author’s relationship with the city from its inhabitants to its architecture. It is this book which informs the starting point of my reading of Marseille, in particular the quote:

Marseille is a series of invented cities, living as stories and images, sometimes original, sometimes borrowed, strung together without too much concern for the joints and overlaps. There are any number of semi-fictional versions of Marseille, competing with one another and often contradictory - the comic seaside village whose inhabitants doze out in the sun; the haven of gangsters and whores with its carefully staged shootouts; the magnificent port, former gateway to the east, now mostly derelict; the multicultural city of immigrants and outcasts, colourful or threatening or bother together; the new city of leisure, capital of the would be land of Provence-California; the city of grainy music videos, with youths shooting up outside mournful housing blocks; the mysterious unknowable city of the Mediterranean coast, with its hills and its limestone coves. All of these cities are found in the many books and films about Marseille, each one based on some actual aspect of the city, but also a projection, an overstatement or deliberate distortion, for somehow Marseille more than most cities lends itself to myths and exaggerations.1

1 William Firebrace, Marseille Mix (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2022), 7-8.

MARSEILLE AND THE MEDITERRANEAN

Marseille’s Connection to Mediterranean Cities

MARSEILLE AND HISTORY

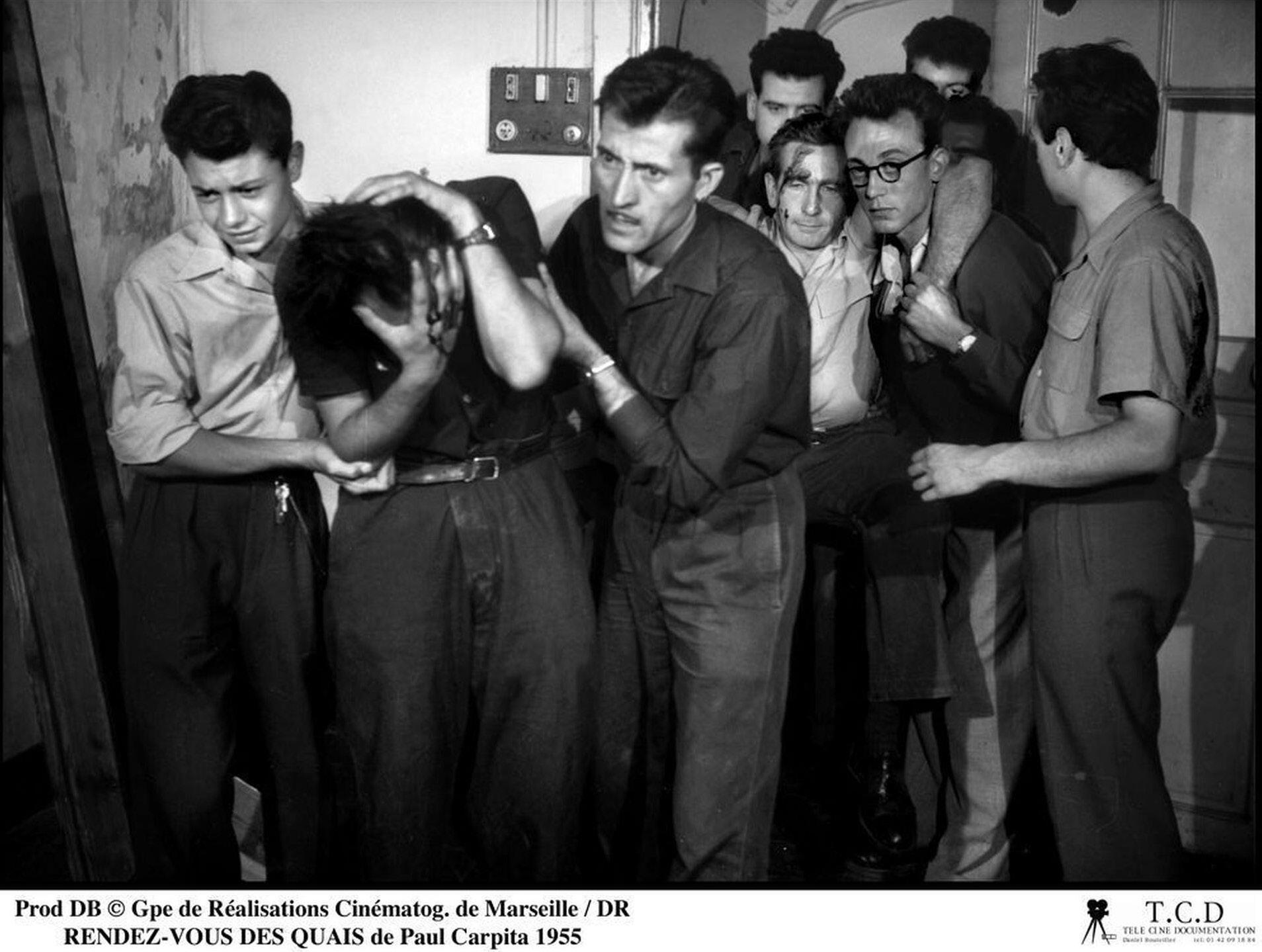

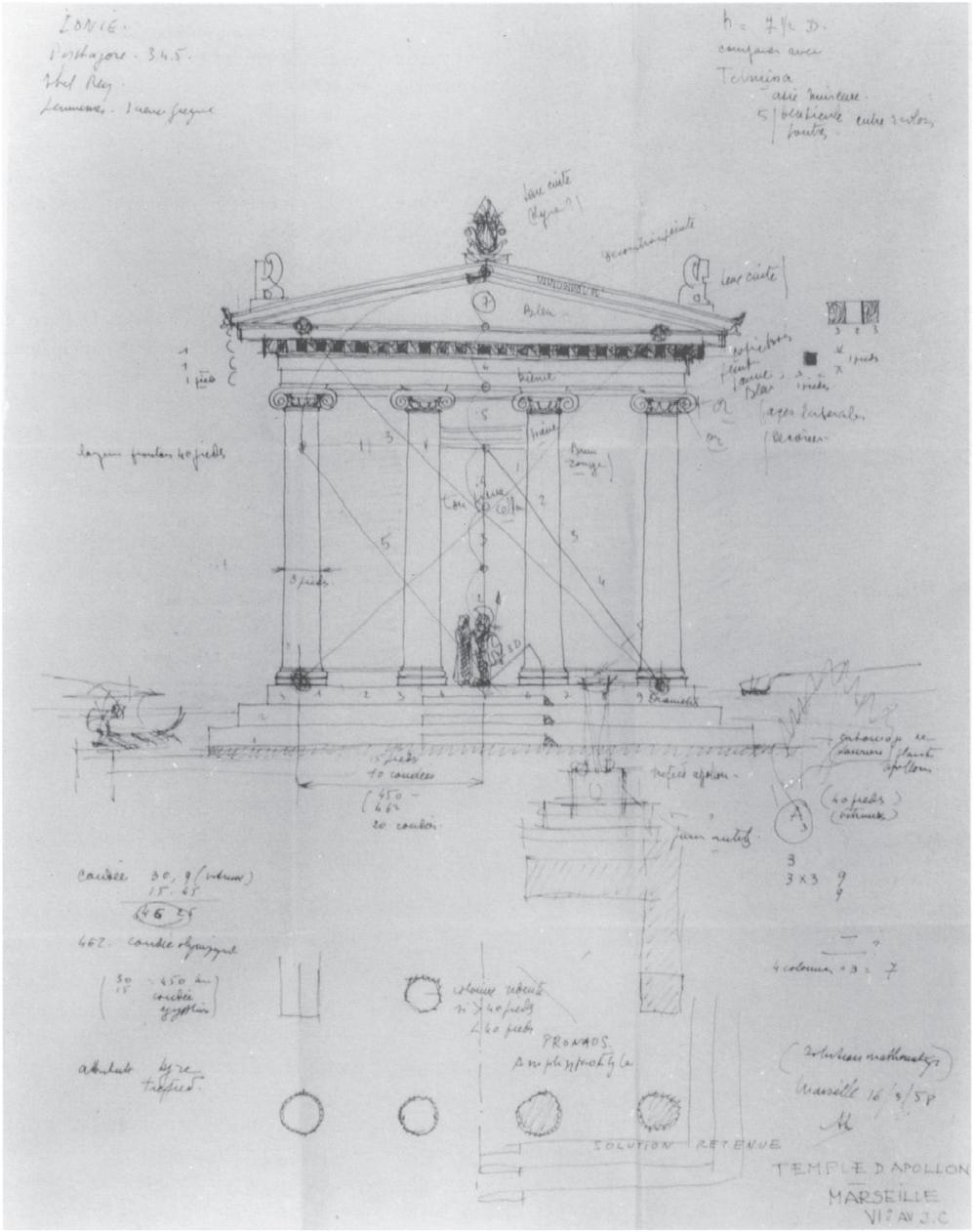

Marseille is the oldest city in France. It is a 2600-year-old port located on the Mediterranean shores of France established by Greek sailors as a trading hub in the Mediterranean.1 Or so its is known in the common image of Marseille. Instead the reality is more complex. The Greek founding myth is the basis for the claim that Marseille is part of the great lineage of classical history linked to democracy and western civilization via the Greeks. Firebrace argues that this myth is an invented origin, one which represents present Marseille’s desired image of itself. He argues that the discovery of the Cosquer cave disputes this time-line and adds a layer of complexity to the truth of Marseille’s origin and consequently its projected image.2

Firebrace argues that Marseille has never valued its own material history instead deliberately seeking to destroy, conceal, or fabricate history in order to pursue more financially more rewarding outcomes.3 This is further backed up by Sheila Crane’s book, Mediterranean Crossroads, which describe the urban renewal projects of the 20th century which sought to rebuild the Vieux Port following its destruction during WW2. Crane argues that during the reconstruction of the Vieux Port, planners and architects were keen to uncover the lost archaeological artefacts from antiquity Marseille. In doing so, planners, architects, and archaeologist went to great lengths manipulating what little artefacts they did find to construct the image of Marseille as fundamental to the historical narrative of France and Provence.4 The extremes of this included the drawing by Andre-Pierre Hardy which reconstructed the Temple to Apollo based on a single Ionic column capital discovered during archaeological excavations in Marseille in 1952.

The converse image of Marseille presented by these attempts at fabricating an image of itself, is of a city which is unsure of how or where it sits in the wider historical narrative of France or Provence.

Marseille is a city which is content to manipulate its material history to present desired images of itself. It is this manipulation, that the thesis aims to utilise.

1 Charlotte Malterre-Barthes, “Marseille: Is There A City Beyond the Cliches?” in Migrant Marseille, ed. Marc Angelil, Charlotte Malterre-Barthes, Julian Schubert, Elena Schutz, Leonard Streich (Berlin: Ruby Press, 2022), 19.

2 Firebrace, 21-23.

3 ibid. 19.

4 Sheila Crane, Mediterranean Crossroads (Minnesota: Minnesota Press) 2011, 260-262.

PORT ANTIQUE

One example of Marseille’s complex relationship to its history is the archaeological site of the ancient port. Discovered in 1967 during the construction of the Centre Bourse shopping mall, the site was opened to the public as the “Jardin des Vestiges” in 1983.

Excavations of the site were conflicted, with a municipality determined to build a shopping centre and a public determined to preserve its ancient history. It was not until 1972 when the Administration of Antiquities intervened and declared the site a historical monument that excavations could begin properly, by then three quarters of the designated archaeological site had been lost.1 The attitude towards one of the largest urban archaeological excavations in post war France, demonstrates the indifference towards history in Marseille. The city is continually more concerned with looking forwards, preferring instead to utilise narrative to construct myths surrounding its history and the resulting historic fabric.

The Port Antique is an interesting element of Marseille as it speaks to the visible contradictions within Marseille. The dialogue between archaeological ruins and existing context is key to understanding Marseille’s relationship to history and conversely how an ethical approach towards historic fabric could engage with the physical manifestations of the heritage of Marseille.

1 Euzennat, Maurice. “Ancient Marseille in the Light of Recent Excavations.” American Journal of Archaeology 84, no. 2 (1980): 133

MODEL OF PORT ANTIQUE

Archaeology Bounded by Commerce

SECTION OF PORT ANTIQUE

Difference of Scale

PLAN OF PORT ANTIQUE

Archaeology is Subservient to Centre Bourse

CONTEXT OF LE PANIER

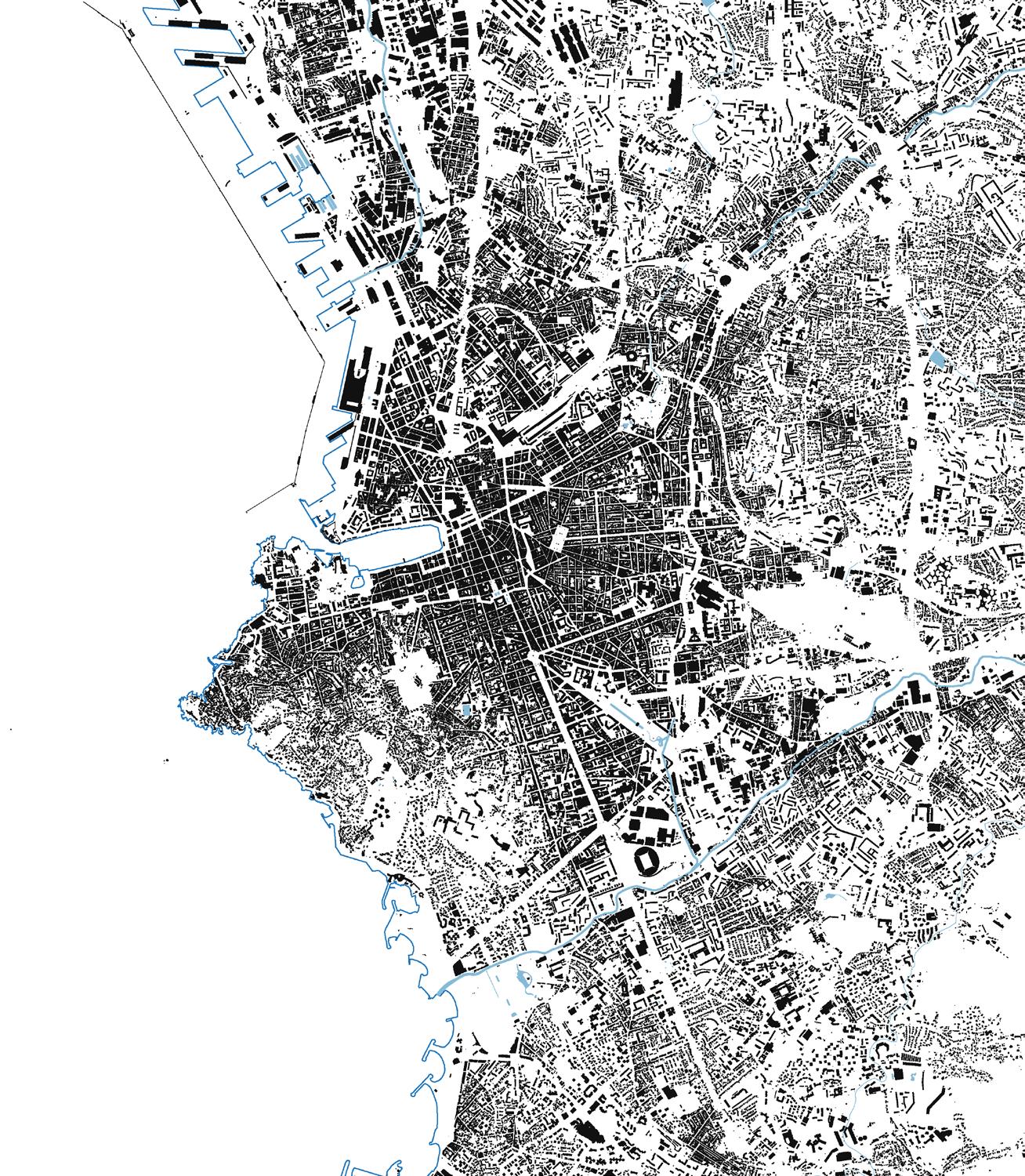

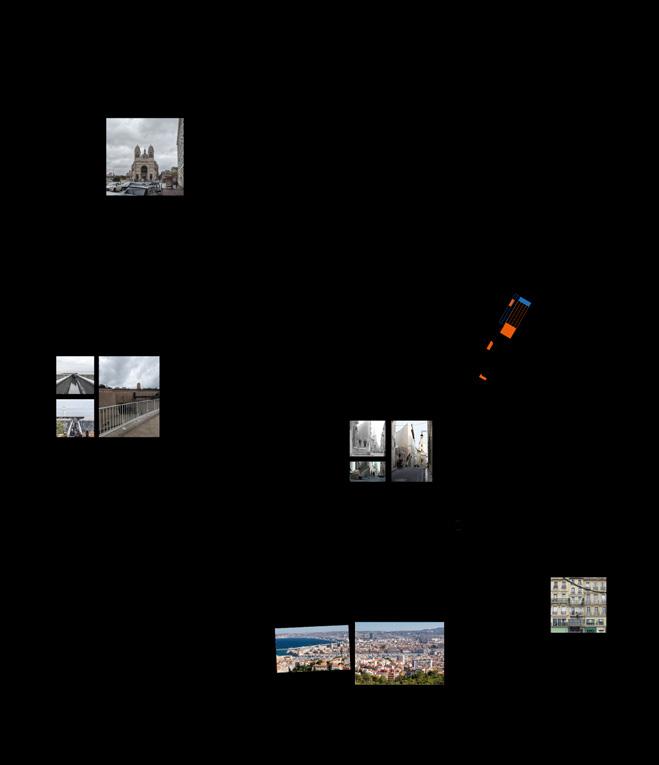

Le Panier is the oldest part of Marseille and the historic centre of the city. It is a symbolic stand in for the entire city. Lazslo Moholy-Nagy’s film: Impressionen vom alten Marseiller Hafen, frames Marseille’s Vieux Port as the symbol for the entire Marseille1 and depicts the complexity of the area 100 years ago. The image presented by Moholy-Nagy is one which is fragmentary and decaying but teeming with life. The film, which is discussed later in this report, emphasises the idiosyncratic nature of Le Panier. It is a part of the city which is both picturesque and dramatic and as a result projects a filmic image of Marseille. This filmic image is the image which the thesis aims to capture and project.

IMAGES IN THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

The result of this reading is an understanding of Marseille as a collection of various images. Malterre-Barthes argues that these images are the substance of the city: the multi-scalar mental territory that evolves through time and composed of its architecture, urbanism, infrastructure, institutions, monuments, and its everyday images.1

It is the intention of this thesis to explore some of the images found of Marseille and to carve from them an architectural response which proposes a more ethical relationship between projected images of the city and the lived experience of the city.

1 Malterre-Barthes, 19-20.

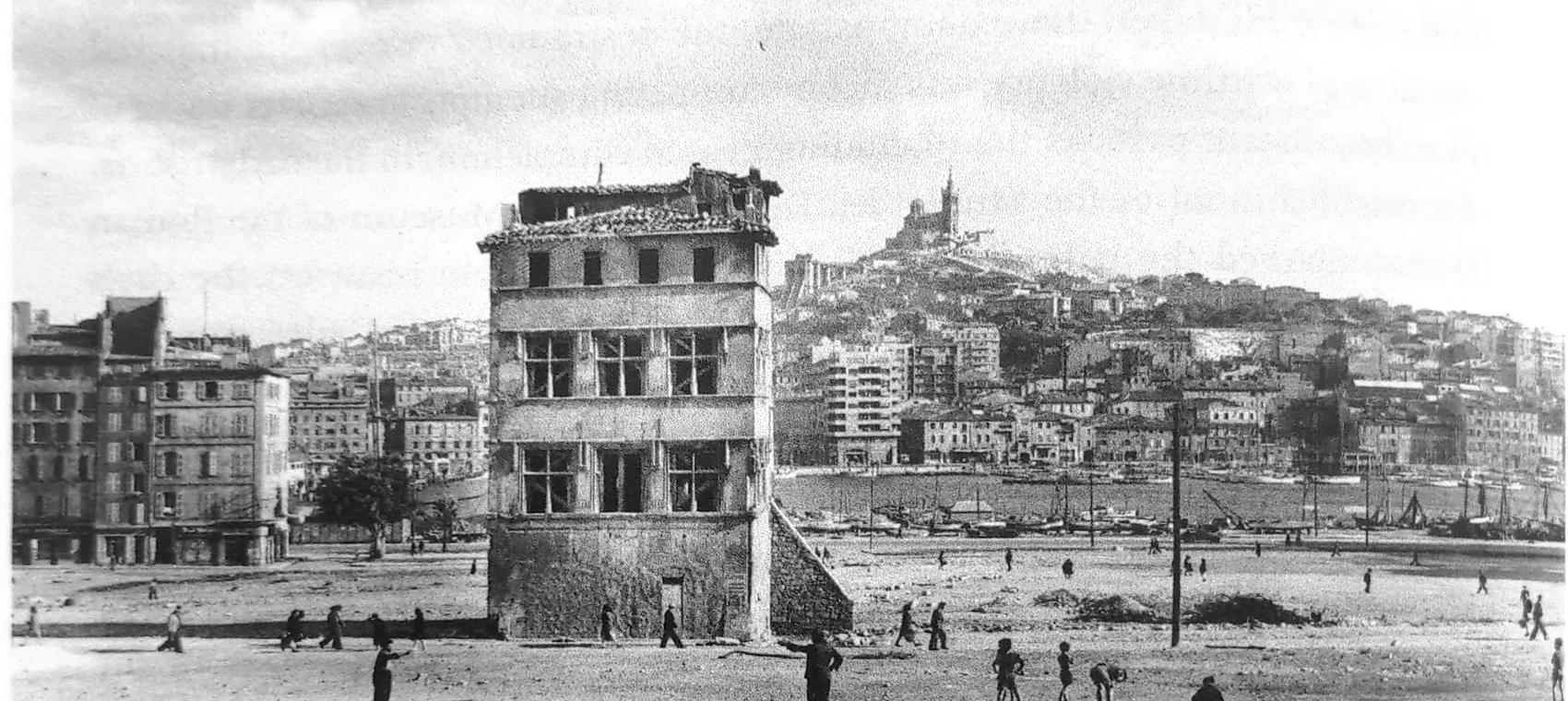

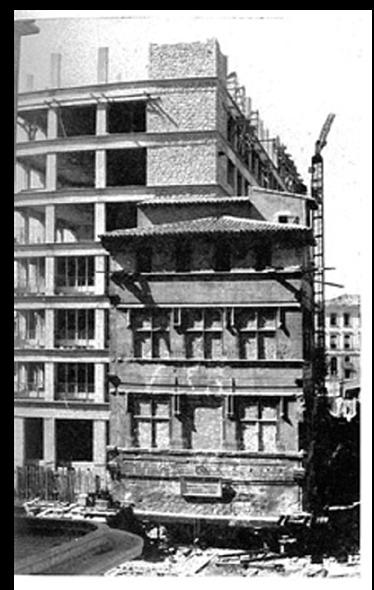

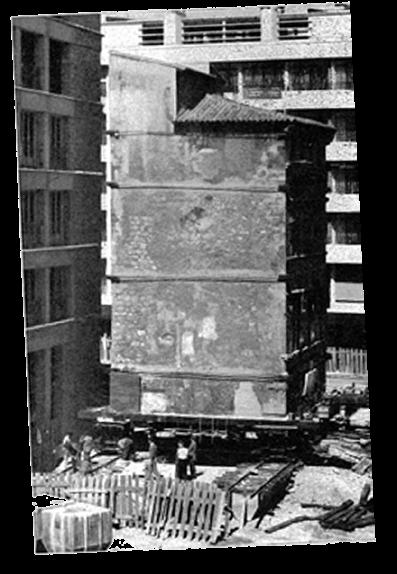

LA VOIE HISTORIQUE

The Historic Route is a public route presented by the Ville de Marseille which links the historically significant sites through Le Panier. The historic route is interesting as it runs through Rue Caisserie which marks the boundary between the remaining historic fabric of Le Panier to the north and the post WW2 development to the south. The result is a “historic route” which is composed of fabricated images of a historical Marseille one which presents the sequential procession of historical sites from the Port Antique, the symbol for Classical Marseille, to the Mucem, the symbol for contemporary Marseille. Furthermore, Crane points to the urban reconstruction evidenced by the displacement of the Hotel de Cabre to align to the new Rue Caisserie.1 The historical images of Marseille often rely on this physical manipulation and symbolism to project particular images about Marseille’s history.

The thesis aims to speculate on how images projected through historical artefacts can be more ethically presented to the public, and how an architectural response can manifest around these artefacts which is more transparent and honest to the actualities of Marseillais history.

1 Crane, 248-250.

MORPHOLOGICAL EVOLUTION OF MARSEILLE

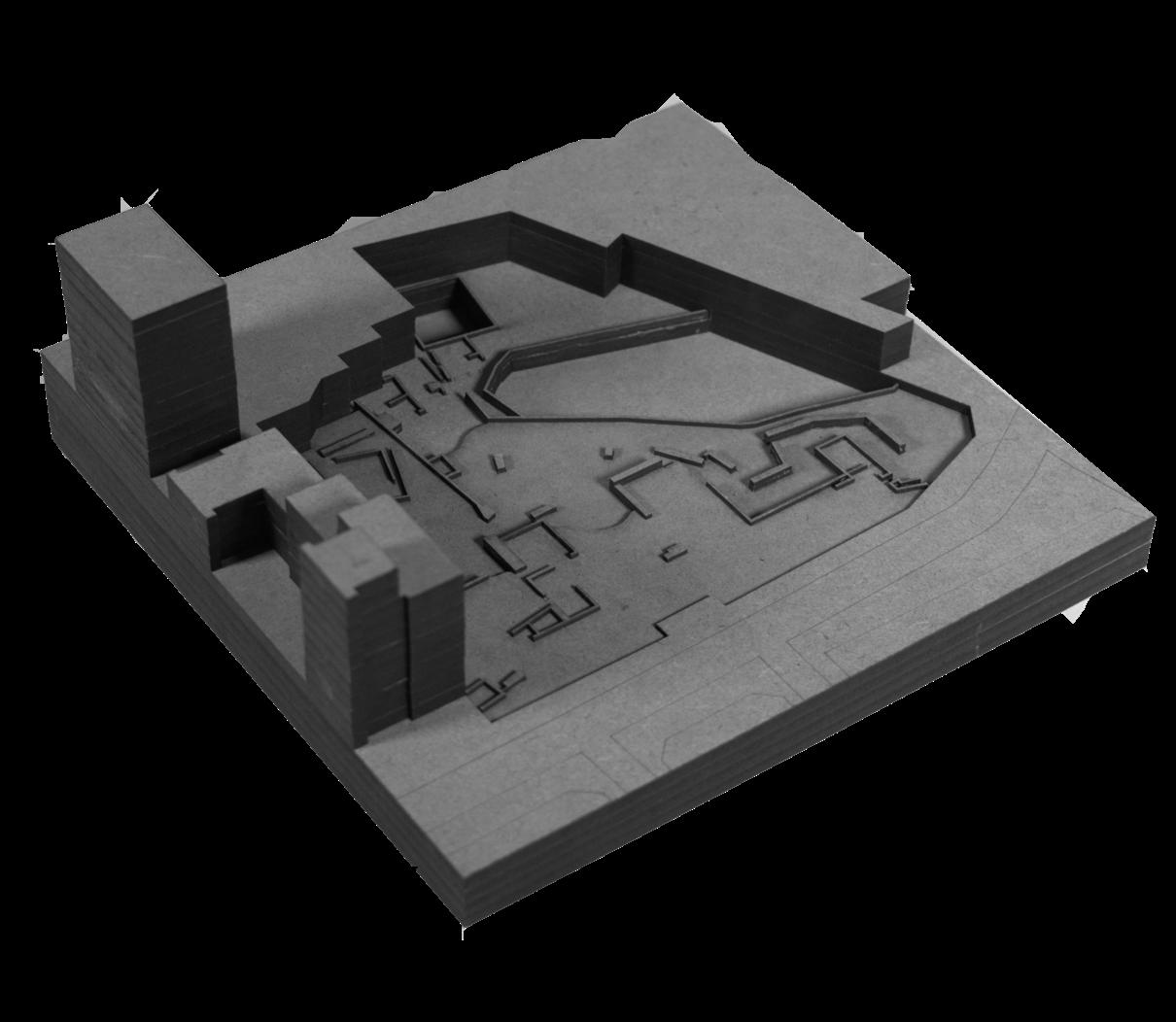

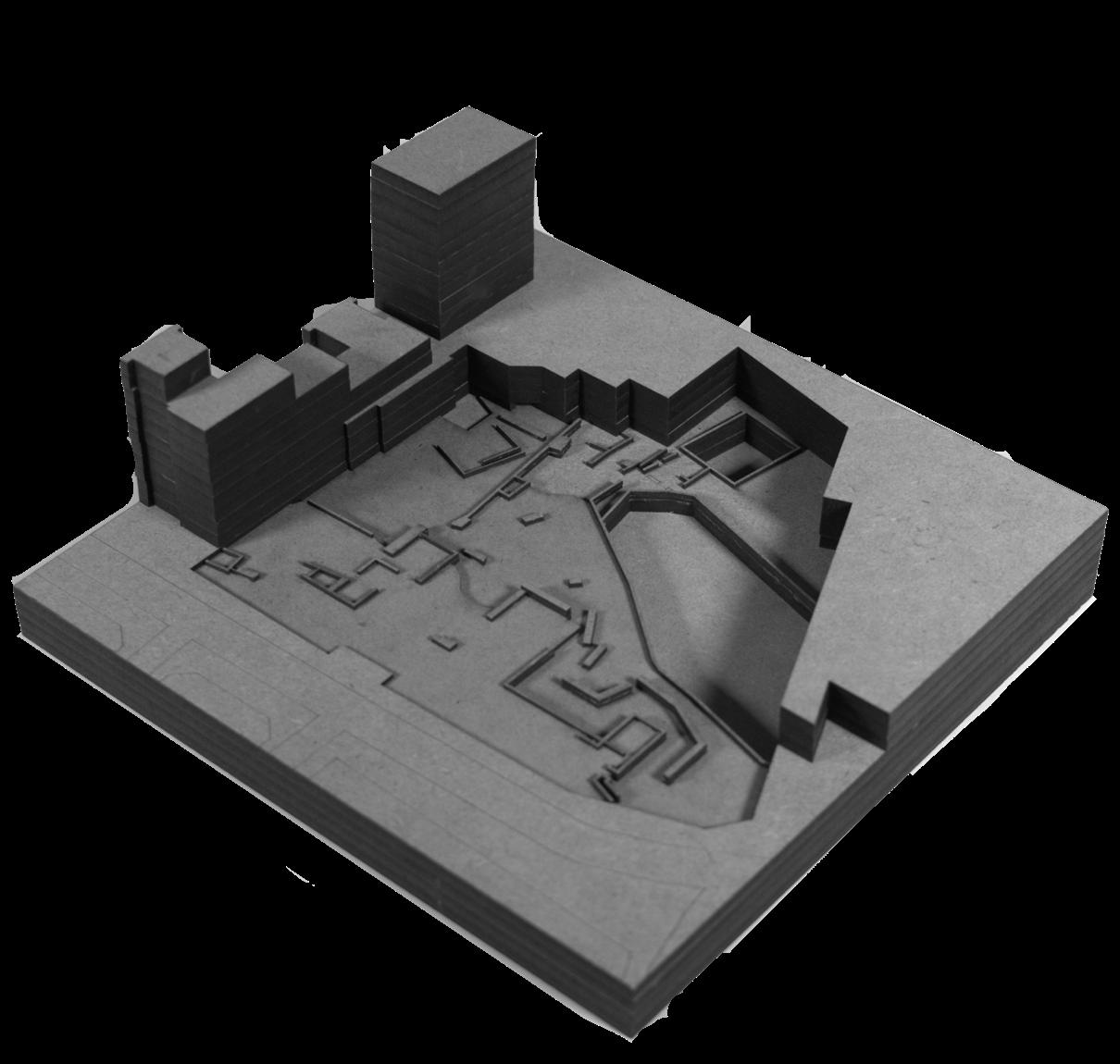

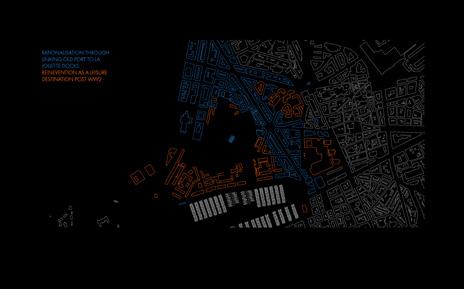

LE PANIER AS PALIMPSEST OF HISTORICAL LAYERS

Le Panier can be read as a palimpsest of historical layers of Marseille. Iterations of urban renewal can be read in the urban fabric of Marseille by studying the density and plots of the buildings which trace out three clear morphological eras of development of the area: the historical city which developed in relation to the Vieux Port, the rational city which developed in relation to La Joilette docks, and the post war city which reconstructed the urban fabric following the destruction of WW2. As a result the layers of the city are traceable in the contemporary form of Le Panier.

HISTORIC CONDITION

RATIONALISATION THROUGH LINKING OLD PORT TO LA JOLIETTE DOCKS

REINEVENTION AS A LEISURE DESTINATION POST WW2

Within the context of the thesis, this means that Le Panier forms a contested territory composed of various images: the historic, the port, the docks, and the new. Viewing the Le Panier as a palimpsest balances out the predominant image of Le Panier as historic and organic Marseille. It allows the thesis to explore images of the city within a part of Marseille which is complex and rich historically.

LE PANIER AS A PALIMPSEST OF HISTORICAL LAYERS

FILMIC LE PANIER

MARSEILLE IN FILM

Shot in 1929 by Hungarian born artist László Moholy-Nagy, the silent short film Impressions of Marseille’s Old Harbour juxtaposes the city in movement with the rampant poverty prevalent in the Vieux Port. Impressions aimed to shed light on the reality behind Marseille’s modern facade,1 in doing so, Moholy-Nagy resists a singular perspective of Marseille. Instead opting to depict the complexity of Marseille’s Vieux Port and consequently the complexity of the whole of Marseille.2

Released in 1971, The French Connection depicts the pursuit of a French heroin smuggler operating out of Marseille.

The film picks up on the existing image of Marseille as a hotbed for criminality. This image is fuelled in part by the lineage of smuggling, gangsters, and political corruption which can be traced throughout Marseille’s history,1 and in part by the stereotype of Marseille as the Gangland City. An image encouraged by the press and by the fiction industry. In turn, the history of criminality in Marseille is created and sustained by the imagined life of the city2 such as that portrayed in The French Connection

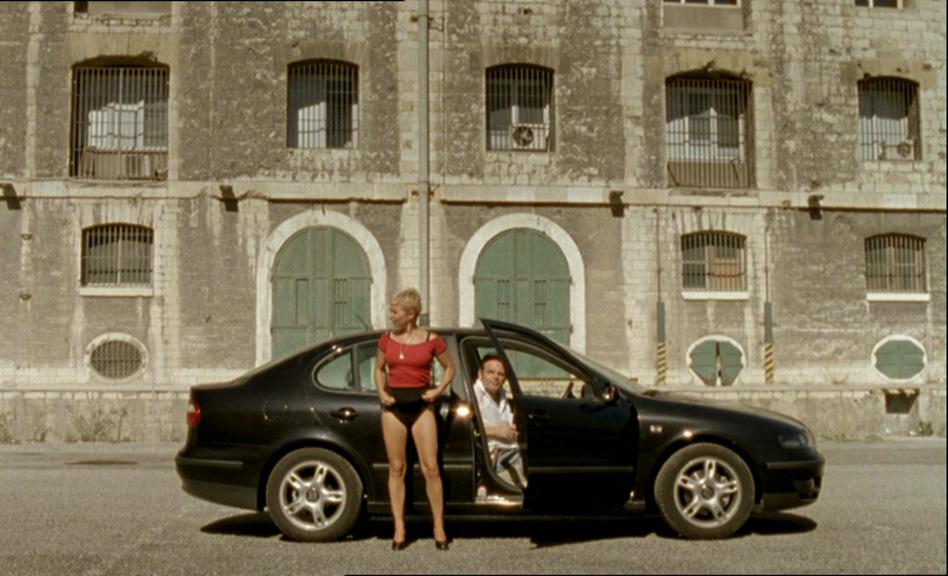

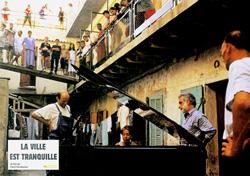

La ville est tranquille is a 2000 film by Marseillais director Robert Guédiguian which depicts various entwined stories which occur in the city.

The film is a portrait of Marseille which feels authentic and optimistic despite its dark story. Marseille is depicted as a fallen city, one which has lost is workforce solidarity and in turn its tolerance. An image of the city as a decaying proletarian city with massive social problems is tempered by its softer side of family life and tranquillity.1 Guédiguian portrays the residual machismo of the city as a result of its industrial heritage, and yet manages to capture a more feminine side of the city. The result is an intimate portrait of Marseille’s complexity.

1 Sheila Crane, Mediterranean Crossroads (Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press, 2011), 59-60.

2 Crane, 51-52.

1 William Firebrace, Marseille Mix (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2022), 154-158.

2 Firebrace, 161.

1 William Firebrace, Marseille Mix (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2022), 187-188.

ACT TWO METHOD

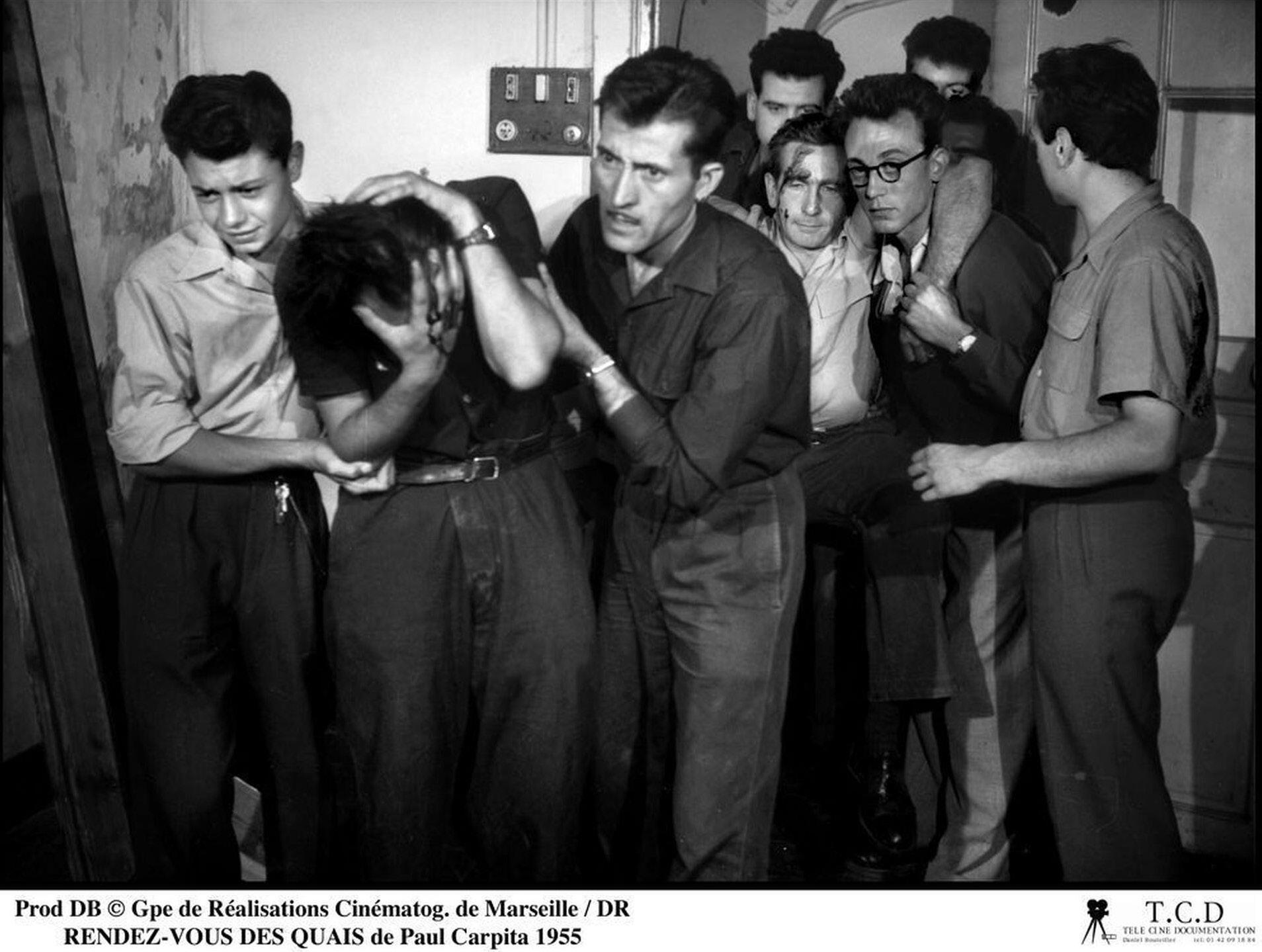

PAUL CARPITA AND WORKING-CLASS REPRESENTATION IN FILM

The “idea of continuity” is typically encouraged by film historians to denote the evolution of French film from the Occupation of WW2 to the French New Wave; wherein, a strong artistic continuity accounts for the similarities between the two periods of French film.1 In contrast to this, Haenni describes the changing prevalence of working-class representation in French film2: the 1930s saw representation of the working-class emerge in French film particularly with the Parisian working class. (HAYWARD, find reference) The 1940s saw their disappearance in French film until the 1960s, with the exception of a brief moment during the late 1940s which saw working-class representation flourish coinciding with brief left-wing political victories following the end of WW2.3 It is within this period that the Marseillais director Paul Carpita operated.

Les Rendez-Vous des Quais is a 1955 film by Marseillais director Paul Carpita. It depicts the struggle of a young working-class couple to find an apartment during housing shortages following WW2 and the dockers strike during the French war in Indochina. The film’s political content contributed to the censorship of the film having upset both the French authorities and the French communist party.4 The film is particularly important for its depiction of the complexity of a differentiated workingclass in Marseille.5

The film does not shy away from articulating the intersection between class oppression and other social issues portraying other roles of womanhood6 and alternative domestic structures. 7 Rendez-Vous is particularly interesting in its depiction of anti-colonial struggles and class oppression. Carpita resists equalling colonialism with class oppression and instead opts to represent how the different external forces interact with different members of the working-class resulting in competing discourses.8 Carpita stresses the individuality of Marseillais identity, and contrasts this to dominant Parisian attitudes, aiming to articulate how working-class culture manifests in Marseille9 and the way in which the

1 Sabine Haenni, “’To Show the People in Paris How We Live Here’: Working-Class Representation, Paul Carpita, and Film History,” Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media 58, no. 1–2 (2017): 79.

2 Haenni, 79-80.

3 Haenni, 80.

4 Haenni, 82-83.

5 Haenni, 86.

6 Rosemarie Scullion, “On the Waterfront: Class Action and Anti-Colonial Engagements in Paul Carpita’s ‘Le Rendez-Vous Des Quais.’” South Central Review 17, no. 3 (2000): 43-45.

7 Scullion, 42-44.

8 Haenni, 86.

9 Haenni, 83.

film resists French attempts to disassociate itself from its colonies.1

Le Rendez-Vous des Quais is better understood as a part of the lineage of working-class representations within a wider context of Marseillais film, rather than as the missing link in French film which connects Neorealism to the French New Wave.2 Haenni argues instead that Rendez-Vous should be understood to be preceded by the work of Renoir, and succeeded by Allio and Guédiguian, placing it within the Marseillais cinematic landscape that gives voice to a complexly differentiated working-class.3 In line with this, Rendez-Vous can also be read as a dissenting voice in France’s postwar campaign to reaffirm patriarchal male values in the light of the Occupation.4 Scullion argues that the image of women in the labour struggle depicted in RendezVous demonstrates the links between class and gender oppression and gives voice to a rich oppositional politics that was otherwise missing from French film during the aftermath of the Occupation.5

Its oppositional politics, the depiction of a complex and differentiated working-class in Marseille, and its censorship make Le Rendez-Vous des Quais an incredibly important film within the cultural heritage of Marseille. It helps to describe the rich history of working-class culture within Marseille and contextualises the strong working-class representation depicted in the likes of more famous Marseillais filmmakers such as Robert Guédiguian.

1 Haenni, 86.

2 Haenni, 80.

3 Haenni, 87.

4 Scullion, 44-45.

5 Scullion, 47.

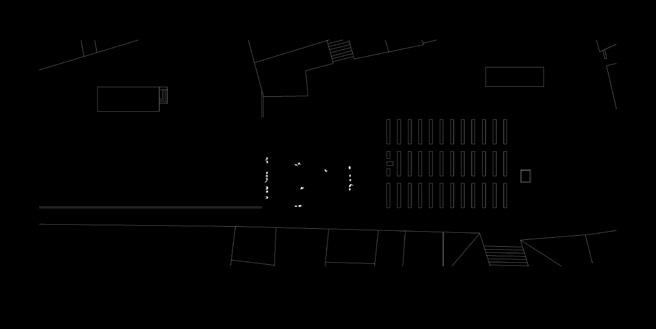

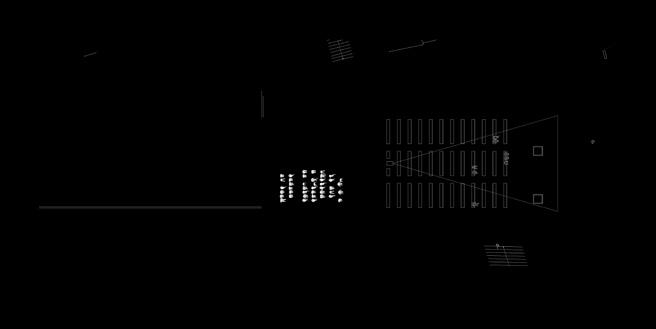

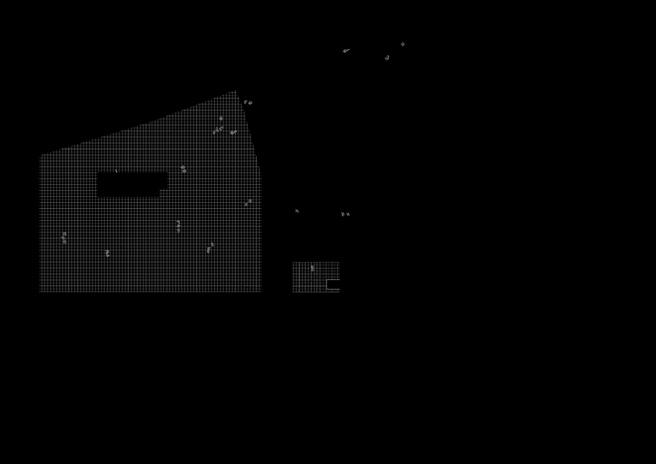

PLACE DES MOULINS

The Place des Moulins is a public plaza in Le Panier, it is the highest point in Le Panier and is accessed primarily through a series of stepped streets and urban stairs which result in a filmic experience of the site. Morphologically, the site is incredibly complex, the topography dictates that buildings which are 1 or 2 stories high at the level of the plaza are 3 or 4 stories high at the level of surrounding streets. The site presents an interesting contradiction of an exposed public space in Le Panier hidden away between thresholds and narrow lanes.

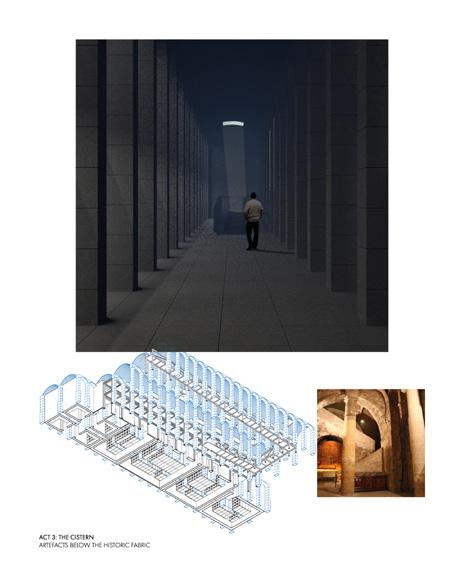

The site presents a further point of interest due to the existence of a disused 19th century water cistern underneath. The vaulted stone structure is buried under the public plaza and presents an opportunity to uncover a historical artefact.

PLACE DES MOULINS LOCATION PLAN

PLACE DES MOULINS PLAN 1:500

SECTION THROUGH PLACE DES MOULINS 1:500

SECTION THROUGH PLACE DES MOULINS 1:500

SECTION THROUGH PLACE DES MOULINS 1:500

SECTION THROUGH PLACE DES MOULINS 1:500

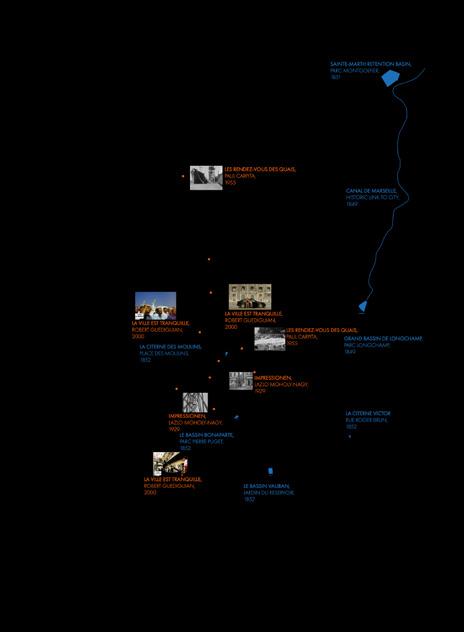

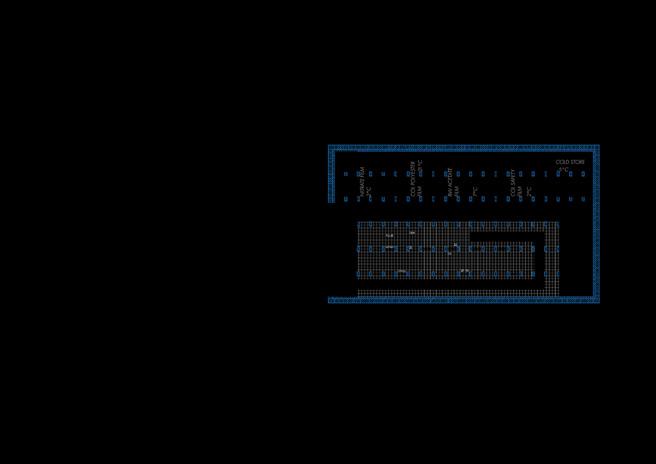

MARSEILLE’S CISTERNS

Marseille’s water cisterns were constructed in the mid-19th century as a means of storing freshwater coming from the newly constructed Canal de Marseille. The canal, in turn, was constructed to divert fresh water from the Durance river to the city following cholera outbreaks in the city. The project represented a significant infrastructural undertaking to cope with the expanding city following the development of the La Joilette docks. The cisterns still remain within the city, disused.

The largest of the cisterns, the Grande-Bassin de Longchamp represented the entry point for the Canal de Marseille and alongside it developed the Palais Longchamp and Parc Longchamp as a means of celebrating the arrival of water into the city. Each of the remaining cisterns were responsible for storing the freshwater supply for the surrounding areas. La Citerne des Moulins, underneath the site of the thesis, provided the water supply for Le Panier and the Hotel de Ville area of Marseille. This metaphor of supply and preservation is introduced into the thesis proposal.

SALON-DE-PROVENCE

AIX-EN-PROVENCE

MARSEILLE’S 2 HISTORIES

Within this context, the thesis focuses on two histories of Marseille: the remaining artefacts of the water cisterns, and Marseille’s filmic heritage. The thesis argues that the Place des Moulins, and more broadly Le Panier, lie at an intersection of these two histories. The existence of la citerne and the various images of Le Panier in film provide an opportunity to explore projected images of Marseille through the rehabilitation of the cistern and the projection of this filmic heritage.

The two vehicles of projection and uncovering are applicable to both histories: the cistern represents a buried artefact to be uncovered, and Paul Carpita represents a filmic heritage to be uncovered; and the cistern represents an image of historic Marseille to be projected alongside the projection of the image of Marseille as a city with a rich filmic heritage.

LA VILLE EST TRANQUILLE, ROBERT GUEDIGUIAN, 2000

LES RENDEZ-VOUS DES QUAIS, PAUL CARPITA, 1955

CANAL DE MARSEILLE, HISTORIC LINK TO CITY, 1849

LA CITERNE DES MOULINS, PLACE DES MOULINS, 1852

IMPRESSIONEN, LAZLO MOHOLY-NAGY, 1929

LA VILLE EST TRANQUILLE, ROBERT GUEDIGUIAN, 2000

LES RENDEZ-VOUS DES QUAIS, PAUL CARPITA, 1955

GRAND BASSIN DE LONGCHAMP, PARC LONGCHAMP, 1849

LE BASSIN BONAPARTE, PARC PIERRE PUGET, 1852

2000

2 HISTORIES OF MARSEILLE FILMIC HISTORY AND ARTEFACTS OF THE CISTERNS

1852

VAUBAN,

IMPRESSIONEN, LAZLO MOHOLY-NAGY, 1929

MARSEILLE CINEMATHEQUE

The programme of the thesis proposal is a cinematheque. The cinematheque balances the functional role of a film archive with the public function of screenings and exhibitions.

A cinematheque is particularly suitable to the thesis as it explores both the act of preservation and projection of filmic heritage.

The programme is similarly suitable to the site as the thesis proposes the transformation of the cistern into a film archive The thesis speculates that the subterranean nature of the cistern makes it both environmentally and metaphorically suitable. The stable ground temperatures theoretically reduce the energy demand necessary to provide the required internal environmental conditions and the historic condition of the cistern as the distributor of the public resource of water makes it metaphorically suitable.

The thesis argues that the film also forms a public resource and as such the cinematheque’s relationship to film and the public is analogous to the cistern’s historic relationship to water and the public.

PROGRAMME ORGANISATION OF THE PROGRAMME

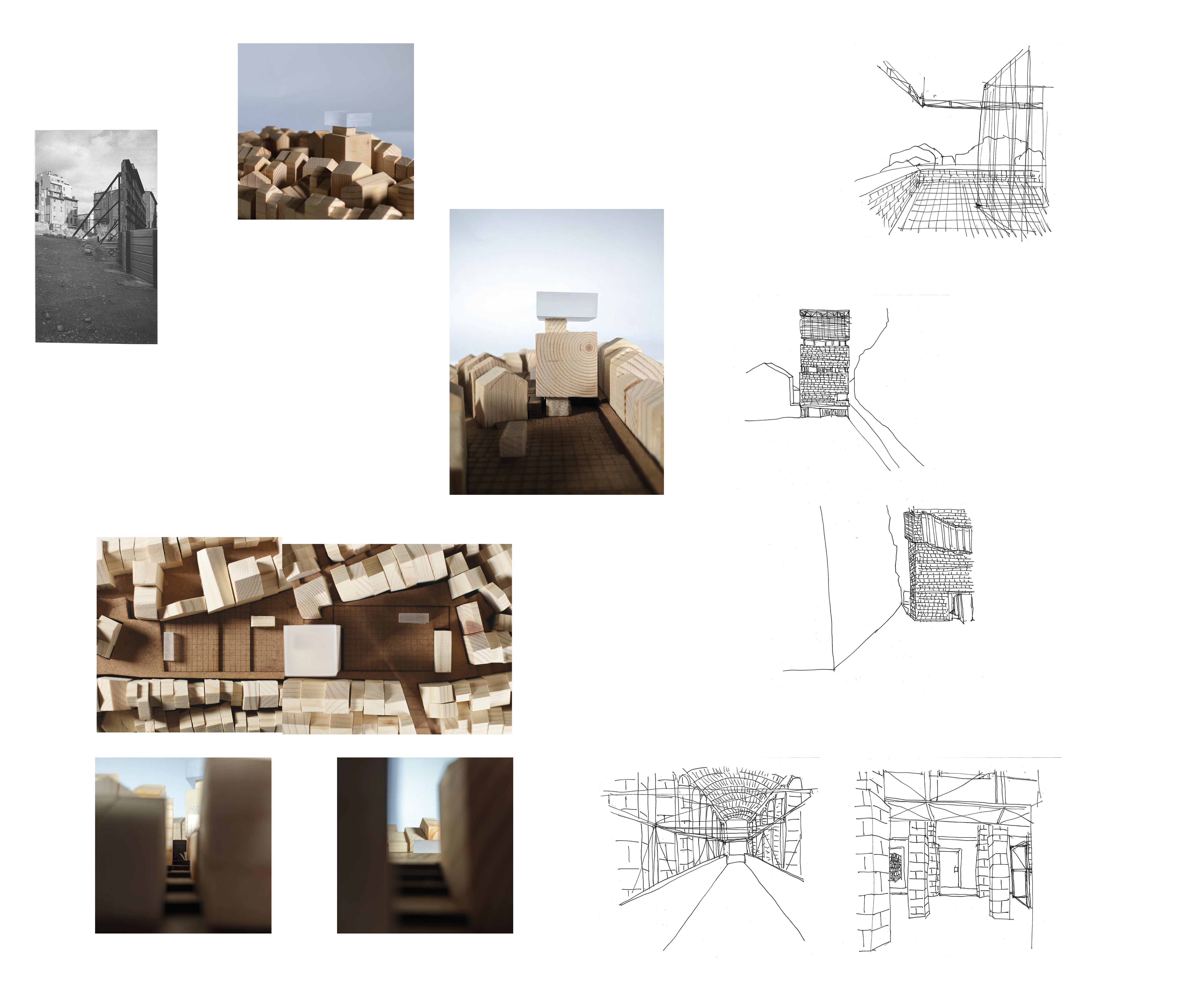

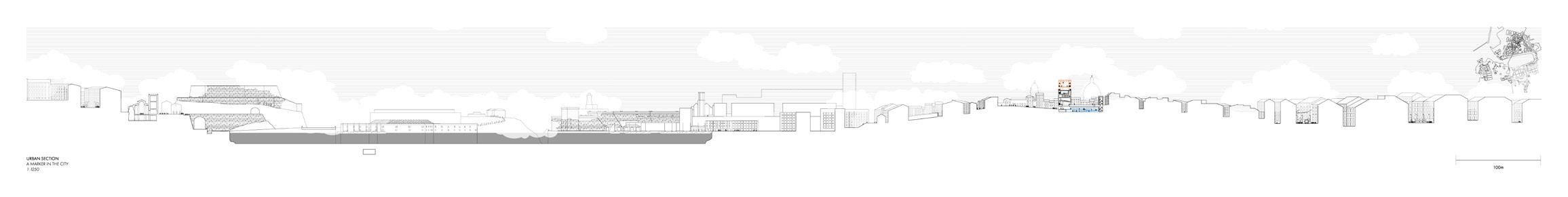

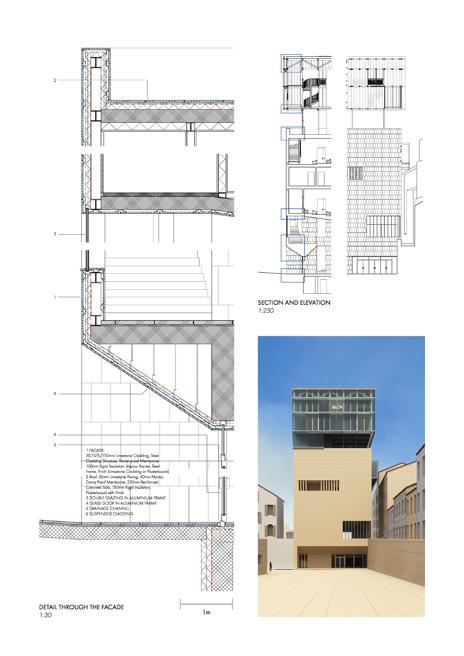

ARCHITECTURAL DRIVERS

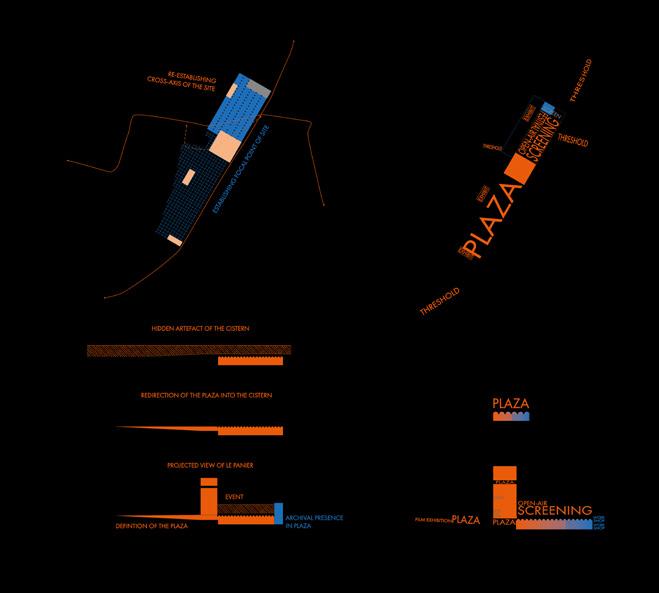

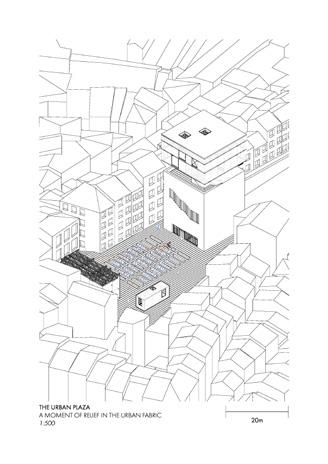

The main architectural drivers of the thesis focus on the concepts of projection and uncovering. The thesis argues that projection and uncovering form methods which fabricate images of the city and as such are relevant to the thesis concept and proposal.

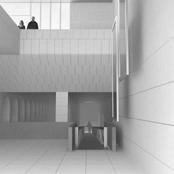

The key urban strategy for the thesis focuses on the rehabilitation of the Place des Moulins site. The thesis argues that the site has a natural theatricality owing to the presence of thresholds and the contrast between the domesticity of the urban fabric and the existence of the hidden cistern. The urban strategy therefore aims to amplify this by promoting the natural theatricality of the site and the uncovering of the historical artefact of the cistern.

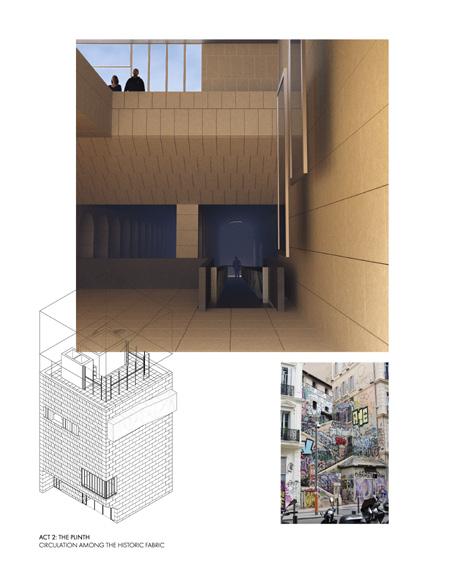

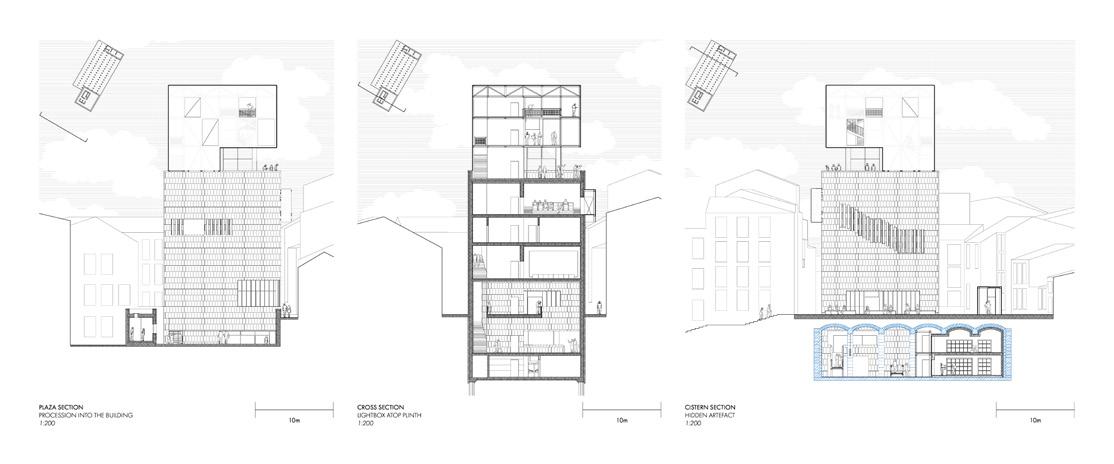

A key architectural line of enquiring concerns the composition of the three Acts of the building: the cistern, the plinth, and the lightbox. This forms the conceptual framework of the thesis proposal.

The key architectural strategy of the thesis consists of the redirection of the public plaza into the cistern and the establishment of belvedere above the historic fabric of Le Panier. These constituent parts are separated by two different types of plaza: the covered and the elevated.

SITE STRATEGY

UNCOVERING THE CISTERN AND THE PROJECTION OF THE BELVEDERE

RE-ESTABLISHINGCROSS-AXIS OF THE SITE

DEVELOPMENT OF THE KEY CONCEPT

The key concepts described in the previous pages are best explored through the key section. The section describes the spatial organisation of the proposal and demonstrates the evolving relationship between the three acts of the building.

The key section presented at the parlour review portrays a first attempt at conveying the relationship between the cistern and the tower. The section details the covered threshold space between the two parts and looks at a larger intervention into the cistern.

The main development of the key section was the development of the vertical circulation which leaned into the existing cinematic forms of vertical circulation found in the built environment of Marseille. The circulation becomes a means of traversing between the different acts of the proposal.

Conversely the key section presented at the final review forms a much more refined image of the relationship between the three acts and outlines the developed cinematic form of the circulation and the qualities of the different types of plazas in the proposal and the scale of intervention into the cistern.

Key Section Presented at Parlour Review 1:500

Key Section Presented at Final Review 1:500

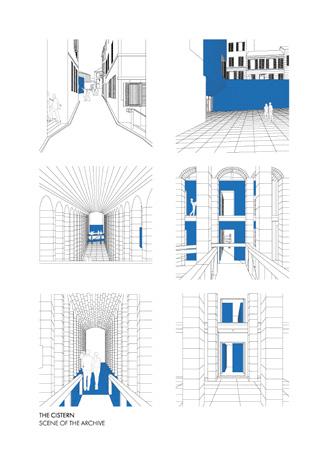

DEVELOPMENT OF THE CINEMATIC LINK

The cinematic link refers to the circulation route from the cistern to the lightbox. The route is explored primarily through the use of unfolded sections and plans. The first draft was presented at the final review, which made explicit the varying condition of spaces along the vertical circulation route. The aim of the drawing was to convey the extremities of the two conditions of the cistern and the lightbox and to contrast these to the changing condition of space along the route.

A final draft is included on the final exhibition board which better conveys the atmospheric conditions of the spaces along the cinematic route.

FINAL EXHIBITION BOARD

CONCLUSIONS

The report has drawn a narrative from the initial reading of Marseille as outlined by William Firebrace as a collection of images, authentic and fiction, and developed this into an attitude towards film and historical artefacts. The report has laid out how this line of enquiry is applicable to Marseille, then Le Panier, then the Place des Moulins. The report has looked at how the uncovering of the cistern and the creation of the belvedere leans into the concepts of projection and uncovering, and how these could translate into an architectural response. The report has outlined how the programme of a cinematheque is suitable to both the thesis and the site, and has tried to draw parallels between the historic function of the cistern to the proposed function of the cinematheque. The report has then laid out the key developments of the proposal: the concept embodied by the key section and the cinematic route through the proposal.

REFLECTIONS

A key point of reflection is that the thesis is still not explicitly evident. The crux of the thesis lies in tying together the two histories of Marseille: its film history and its remaining artefacts of the cisterns. There is still a bit of work to be done to make explicit the link between these two histories and to convey how they culminate in the proposal.

Another key point of reflection is the development of the cinematic link. Other mediums should have been utilised to explore the different atmospheres along the route. A model would have been most appropriate for this. One precedent for this, is OMA’s Dutch Embassy in Berlin, where various models are produced to isolate the trajectory route through the building.

The last point of reflection refers to the focus of the thesis proposal: the proposal should have focused mostly on the reuse of the cistern. A more thorough resolution to the structural and technical issues presented by the transformation of the cistern would have helped to present the thesis as an exercise in adaptive reuse. This should have formed the majority of the thesis proposal.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Angelil, Marc, Charlotte Malterre-Barthes, Julian Schubert, Leonard Streich. Migrant Marseille Berlin: Ruby Press, 2022.

Crane, Sheila. Mediterranean Crossroads. Minnesota: Minnesota Press, 2011.

Crane, Sheila. “Digging up the Present in Marseille’s Old Port: Toward an Archaeology of Reconstruction.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 63, no. 3 (2004): 296–319.

Euzennat, Maurice. “Ancient Marseille in the Light of Recent Excavations.” American Journal of Archaeology 84, no. 2 (1980): 133.

Firebrace, William. Marseille Mix. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2022.

Haenni, Sabine. “’To Show the People in Paris How We Live Here’: Working-Class Representation, Paul Carpita, and Film History,” Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media 58, no. 1–2 (2017): 79.

Scullion, Rosemarie. “On the Waterfront: Class Action and Anti-Colonial Engagements in Paul Carpita’s ‘Le Rendez-Vous Des Quais.’” South Central Review 17, no. 3 (2000): 43-45.