AGENDA

I.Welcome/Introduction(5minutes)

II.SIJSBasics(10minutes)

III.StepOne:FamilyCourt(30minutes)

IV.StepsTwoandThree:USCIS(15minutes)

V.WorkingwithSIJSClients(15minutes)

VI.GettingStarted(10minutes)

VII.Q&A(5minutes)

I.Welcome/Introduction(5minutes)

II.SIJSBasics(10minutes)

III.StepOne:FamilyCourt(30minutes)

IV.StepsTwoandThree:USCIS(15minutes)

V.WorkingwithSIJSClients(15minutes)

VI.GettingStarted(10minutes)

VII.Q&A(5minutes)

SamanthaRumsey

SamanthaRumseyistheLegalDirectoroftheNewJerseyConsortiumforImmigrantChildren (NJCIC),astate-widelegalservicesandpolicyadvocacyorganizationdedicatedtoempowering youngimmigrants.NJCIC'slegalteamprovidesholistic,youth-centeredlegalrepresentationto unaccompaniedchildrenandotherimmigrantyouththroughouttheGardenStateandservesasthe centralintakeandreferralhubforNewJersey'sLegalRepresentationforChildrenandYouth Program(LRP).NJCIC'sprojectsincludeFlorecer,amedical-legalpartnershipwithZufallHealth, andaneducational-legalpartnershipwithJerseyCityPublicSchools.Samanthahasovertenyears ofexperiencerepresentingimmigrantchildren,adultasylumseekers,andadultsinimmigration detention.

BeforejoiningNJCIC,SamanthawasaSeniorAttorneyattheNewarkOfficeofKidsInNeedof Defense(KIND)andaStaffAttorneyintheImmigrantRightsClinicatRutgersLawSchool. SamanthareceivedherJ.D.fromSetonHallUniversitySchoolofLawandherB.A.in InternationalRelationsandHispanicStudiesfromtheCollegeofWilliamandMary.

EmeraldSheay

EmeraldSheay,Esq.isastaffattorneyatVolunteerLawyersforJusticewhofocusesonprobono recruitment,training,andcaseplacement.EmeraldadditionallysupportsVLJ’sChildren’s RepresentationProgram,DivorceProgram,andPRIDENameChangeProgram.Priortojoining VLJ,Emeraldpracticedfamilylaw,andclerkedfortheHonorableLisaF.Chrystal,P.J.F.P.atthe SuperiorCourtofNewJersey–FamilyDivisioninUnionCounty.Emeraldalsovolunteeredwith VLJ’sDivorceProgramwhileinprivatepractice.

Emeraldisespeciallypassionateaboutadvocatingforthosewithoutaccesstothejudicialprocess, includingchildrenandanimals.ShesharesthesentimentofformerAttorneyGeneralJanetReno thatlawyerswhoengagein“probonoservicetoprotectthosewhocannothelpthemselvesare trulytheheroesandtheheroinesofthelegalprofession.”EmeraldcurrentlysitsastheCo-Chair oftheNewJerseyStateBarAssociation’sAnimalWelfareCommittee.Shehaspublishedarticles onfamilylaw,animallaw,andempatheticlawyeringintheAnimalLawReview,NewJersey LawyerMagazine,andNewJerseyFamilyLawyer.Emeraldearnedabachelor’sdegreesumma cumlaudeinmusicfromRowanUniversityandaJurisDoctoratecumlaudefromSetonHallLaw School,whereshereceivedthe“Dean’sAward”upongraduation.Sheisadmittedtopracticein NewJerseyandtheUnitedStatesDistrictCourtofNewJersey.

OutsideofVLJ,EmeraldperformswithprofessionalchamberchoirVocalaEnsemble,andisan activememberoftheUnionCountyBarAssociation.

Copy Citation

This document is current through the September 19, 2025 issue of the Federal Register, with the exception of the amendments appearing at 90 FR 44496 and 90 FR 45140.

LEXISNEXIS’ CODE OF FEDERAL REGULATIONS Title 8 Aliens and Nationality Chapter I — Department of Homeland Security (Immigration and Naturalization) Subchapter B — Immigration Regulations Part 204 — Immigrant Petitions Subpart A — Immigrant Visa Petitions

§204.11

(a) Definitions. As used in this section, the following definitions apply to a request for classification as a special immigrant juvenile.

Judicial determination means a conclusion of law made by a juvenile court.

Juvenile court means a court located in the United States that has jurisdiction under State law to make judicial determinations about the dependency and/or custody and care of juveniles.

Petition means the form designated by USCIS to request classification as a special immigrant juvenile and the act of filing the request.

Petitioner means the alien seeking special immigrant juvenile classification.

State means the definition set out in section 101(a)(36) of the Act, including an Indian tribe, tribal organization, or tribal consortium, operating a program under a plan approved under 42 U.S.C. 671

United States means the definition set out in section 101(a)(38) of the Act.

(b) Eligibility. A petitioner is eligible for classification as a special immigrant juvenile under section 203(b)(4) of the Act as described at section 101(a)(27)(J) of the Act, if they meet all of the following requirements:

(1) Is under 21 years of age at the time of filing the petition;

(2) Is unmarried at the time of filing and adjudication;

(3) Is physically present in the United States;

(4) Is the subject of a juvenile court order(s) that meets the requirements under paragraph (c) of this section; and

(5) Obtains consent from the Secretary of Homeland Security to classification as a special immigrant juvenile. For USCIS to consent, the request for SIJ classification must be bona fide, which requires the petitioner to establish that a primary reason the required juvenile court determinations were sought was to obtain relief from parental abuse, neglect, abandonment, or a similar basis under State law.

USCIS may withhold consent if evidence materially conflicts with the eligibility requirements in paragraph (b) of this section such that the record reflects that the request for SIJ classification was not bona fide. USCIS approval of the petition constitutes the granting of consent.

(c) Juvenile court order(s).

(1) Court-ordered dependency or custody and parental reunification determination. The juvenile court must have made certain judicial determinations related to the petitioner’s custody or dependency and determined that the petitioner cannot reunify with their parent(s) due to abuse, neglect, abandonment, or a similar basis under State law.

(i) The juvenile court must have made at least one of the following judicial determinations related to the petitioner’s custodial placement or dependency in accordance with State law governing such determinations:

(A) Declared the petitioner dependent upon the juvenile court; or

(B) Legally committed to or placed the petitioner under the custody of an agency or department of a State, or an individual or entity appointed by a State or juvenile court.

(ii) The juvenile court must have made a judicial determination that parental reunification with one or both parents is not viable due to abuse, abandonment, neglect, or a similar basis under State law. The court is not required to terminate parental rights to determine that parental reunification is not viable.

(2) Best interest determination.

(i) A determination must be made in judicial or administrative proceedings by a court or agency recognized by the juvenile court and authorized by law to make such decisions that it would not be in the petitioner’s best interest to be returned to the petitioner’s or their parent’s country of nationality or last habitual residence.

(ii) Nothing in this part should be construed as altering the standards for best interest determinations that juvenile court judges routinely apply under relevant State law.

(3) Qualifying juvenile court order(s).

(i) The juvenile court must have exercised its authority over the petitioner as a juvenile and made the requisite judicial determinations in this paragraph under applicable State law to establish eligibility.

(ii) The juvenile court order(s) must be in effect on the date the petitioner files the petition and continue through the time of adjudication of the petition, except when the juvenile court’s jurisdiction over the petitioner terminated solely because:

(A) The petitioner was adopted, placed in a permanent guardianship, or another child welfare permanency goal was reached, other than reunification with a parent or parents with whom the court previously found that reunification was not viable; or

(B) The petitioner was the subject of a qualifying juvenile court order that was terminated based on age, provided the petitioner was under 21 years of age at the time of filing the petition.

(d) Petition requirements. A petitioner must submit all of the following evidence, as applicable to their petition:

(1) Petition. A petition by or on behalf of a juvenile, filed on the form prescribed by USCIS in accordance with the form instructions.

(2) Evidence of age. Documentary evidence of the petitioner’s age, in the form of a valid birth certificate, official government-issued identification, or other document that in USCIS’ discretion establishes the petitioner’s age. Under no circumstances is the petitioner compelled to submit evidence that would conflict with paragraph (e) of this section.

(3) Juvenile court order(s). Juvenile court order(s) with the judicial determinations required by paragraph (c) of this section. Where the best interest determination was made in administrative proceedings, the determination may be provided in a separate document issued in those proceedings.

(4) Evidence of a similar basis. When the juvenile court determined parental reunification was not viable due to a basis similar to abuse, neglect, or abandonment, the petitioner must provide evidence of how the basis is legally similar to abuse, neglect, or abandonment under State law. Such evidence must include:

(i) The juvenile court’s determination as to how the basis is legally similar to abuse, neglect, or abandonment under State law; or

(ii) Other evidence that establishes the juvenile court made a judicial determination that the legal basis is similar to abuse, neglect, or abandonment under State law

(5) Evidentiary requirements for DHS consent. For USCIS to consent, the juvenile court order(s) and any supplemental evidence submitted by the petitioner must include the following:

(i) The factual basis for the requisite determinations in paragraph (c) of this section; and

(ii) The relief from parental abuse, neglect, abandonment, or a similar basis under State law granted or recognized by the juvenile court. Such relief may include:

(A) The court-ordered custodial placement; or

(B) The court-ordered dependency on the court for the provision of child welfare services and/or other court-ordered or court-recognized protective or remedial relief, including recognition of the petitioner’s placement in the custody of the Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Refugee Resettlement.

(6) U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) consent. The petitioner must provide documentation of specific consent from HHS with the petition when:

(i) The petitioner is, or was previously, in the custody of HHS; and

(ii) While in the custody of HHS, the petitioner obtained a juvenile court order that altered the petitioner’s HHS custody or placement status.

(e) No contact. During the petition or interview process, USCIS will take no action that requires a petitioner to contact the person(s) who allegedly battered, abused, neglected, or abandoned the petitioner (or the family member of such person(s)).

(f) Interview. USCIS may interview a petitioner for special immigrant juvenile classification in accordance with 8 CFR 103.2(b). If an interview is conducted, the petitioner may be accompanied by a trusted adult at the interview. USCIS may limit the number of persons present at the interview, except that the petitioner’s attorney or accredited representative of record may be present.

(g) Time for adjudication.

(1) In general, USCIS will make a decision on a petition for classification as a special immigrant juvenile within 180 days of receipt of a properly filed petition. The 180 days does not begin until USCIS has received all of the required evidence in paragraph (d), and the time period will be reset or suspended as described in 8 CFR 103.2(b)(10)(i).

(2) When a petition for special immigrant juvenile classification and an application for adjustment of status to lawful permanent resident are pending at the same time, a request for evidence relating to the separate application for adjustment of status will not stop or suspend the 180-day period for USCIS to decide on the petition for SIJ classification.

(h) Decision. USCIS will notify the petitioner of the decision made on the petition, and, if the petition is denied, of the reasons for the denial, pursuant to 8 CFR 103.2(b) and 103.3. If the petition is denied, USCIS will provide notice of the petitioner’s right to appeal the decision, pursuant to 8 CFR 103.3.

(i) No parental immigration rights based on special immigrant juvenile classification. The natural or prior adoptive parent(s) of a petitioner granted special immigrant juvenile classification will not be accorded any right, privilege, or status under the Act by virtue of their parentage. This prohibition applies to all of the petitioner’s natural and prior adoptive parent(s).

(j) Revocation.

(1) Automatic revocation. USCIS will issue a notice to the beneficiary of an approved petition for special immigrant juvenile classification of an automatic revocation under this paragraph as provided in 8 CFR 205.1. The approval of a petition for classification as a special immigrant juvenile made under this section is revoked as of the date of approval if any one of the following circumstances occurs before the decision on the beneficiary’s application for adjustment of status to lawful permanent resident becomes final:

(i) Reunification of the beneficiary with one or both parents by virtue of a juvenile court order, where a juvenile court previously deemed reunification with that parent, or both parents, not viable due to abuse, neglect, abandonment, or a similar basis under State law; or

(ii) Administrative or judicial proceedings determine that it is in the beneficiary’s best interest to be returned to the country of nationality or last habitual residence of the beneficiary or of their parent(s).

(2) Revocation on notice. USCIS may revoke an approved petition for classification as a special immigrant juvenile for good and sufficient cause as provided in 8 CFR 205.2.

Authority Note Applicable to 8 CFR Ch. I, Subch. B, Pt. 204

History

[56 FR 23208, May 21, 1991; redesignated at 58 FR 42849, Aug. 12, 1993; 58 FR 42850, Aug. 12, 1993; 74 FR 26933, 26937, June 5, 2009; 87 FR 13066, 13111, Mar. 8, 2022]

Annotations

Notes

[EFFECTIVE DATE NOTE:

74 FR 26933 , 26937, June 5, 2009, revised paragraph (b), effective July 6, 2009; 87 FR 13066, 13111, Mar. 8, 2022, revised this section, effective Apr. 7, 2022.]

Notes to Decisions

Administrative Law: Agency Adjudication: Hearings: Evidence

Constitutional Law: Equal Protection: Parentage

Family Law: Child Custody: Jurisdiction

Family Law: Child Custody: Jurisdiction: Subject Matter Jurisdiction

Family Law: Family Protection & Welfare: Children: Proceedings

Family Law: Guardians Governments: Courts: Authority to Adjudicate

Immigration Law: Adjustment of Status: Administrative Proceedings

Immigration Law: Adjustment of Status: Eligibility

Immigration Law: Asylum & Related Relief

Immigration Law: Deportation & Removal: Relief: Suspension of Deportation

Immigration Law: Duties & Rights of Aliens: General Overview

Immigration Law: Immigrants

Immigration Law: Immigrants: Special Immigrants

Administrative Law: Agency Adjudication: Hearings: Evidence

Budhathoki v. Nielsen, 898 F.3d 504, 2018 U.S. App. LEXIS 21377 (5th Cir. 2018)

Overview: The agency properly considered the effect of the state court order under Tex. Fam. Code Ann. § 101.032 of Suits Affecting Parent-Child Relationship (SAPCR) because the agency had an obligation to review the SAPCR order, which was for child support, and consider its impact on the petitioner’s applications for Special Immigrant Juvenile (SIJ) status.

•

Constitutional Law: Equal Protection: Parentage

M.B. v. Quarantillo, 301 F.3d 109, 2002 U.S. App. LEXIS 17412 (3d Cir. 2002).

Alberto v. State (In re Luis J.), 300 Neb. 659, 915 N.W.2d 589, 2018 Neb. LEXIS 136 (Neb. 2018).

Overview: A county court erred in finding it was not a juvenile court authorized to make findings needed for a child to seek special juvenile immigrant status under 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J), because, under amended Neb. Rev. Stat. § 43-1238(b) (Reissue 2016), having awarded guardianship of the child, it had jurisdiction to make such findings.

•

In order to achieve special immigrant juvenile status, an individual whose custody has been determined prior to age 21, 8 C.F.R. § 204.11, must have obtained the judicial determinations listed in 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(i) and (ii) from a “juvenile court,” as that term is used in the federal provisions. The Code of Federal Regulations defines “juvenile court” as a court located in the United States having jurisdiction under state law to make judicial determinations about the custody and care of juveniles. 8 C.F.R. § 204.11(a). A Nebraska county court which properly appoints a guardian for a juvenile makes a custody determination, and thus, a county court is considered a “juvenile court” for purposes of 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(i) and (ii). A guardianship over a juvenile renders the juvenile subject to 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(i) Go To Headnote

Family Law: Child Custody: Jurisdiction: Subject Matter Jurisdiction

Gonzalez v. State (In re Carlos D.), 300 Neb. 646, 915 N.W.2d 581, 2018 Neb. LEXIS 135 (Neb. 2018).

Overview: A county court erred in finding it could not make findings required to seek special immigrant juvenile status under 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J) because, having granted guardianship of the subject child, it was, pursuant to amended Neb. Rev. Stat. § 43-1238(b) (Reissue 2016), a “juvenile court” authorized to make such findings.

• The agency obligation to review state court orders for their sufficiency is the approach of the regulations identifying the documents that must be submitted in support of Special Immigrant Juvenile (SIJ) status: (2) One or more documents which include: (i) A juvenile court order, issued by a court of competent jurisdiction located in the United States, showing that the court has found the beneficiary to be dependent upon that court; (ii) A juvenile court order, issued by a court of competent jurisdiction located in the United States, showing that the court has found the beneficiary eligible for long-term foster care; and (iii) Evidence of a determination made in judicial or administrative proceedings by a court or agency recognized by the juvenile court and authorized by law to make such decisions, that it would not be in the beneficiary’s best interest to be returned to the country of nationality or last habitual residence of the beneficiary or of his or her parent or parents. 8 C.F.R. § 204.11(d) Go To Headnote

In order to achieve special immigrant juvenile status, an individual whose custody has been determined prior to age 21, 8 C.F.R. § 204.11 (2018), must also obtain the judicial determinations listed in 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(i) and (ii) from a “juvenile court,” as that term is used in the federal provisions. The Code of Federal Regulations defines “juvenile court” as a court located in the United States having jurisdiction under state law to make judicial determinations about the custody and care of juveniles. 8 C.F.R. § 204.11(a). A guardianship of a child is a child custody determination, and thus, a county court is considered a “juvenile court” for purposes of 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(i) and (ii). A guardianship over a juvenile renders the juvenile subject to 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(i). Go To Headnote

Family Law: Family Protection & Welfare: Children: Proceedings

Romero v. Perez, 463 Md. 182, 205 A.3d 903, 2019 Md. LEXIS 163 (2019)

Overview: In a case involving whether an undocumented minor was eligible for special immigrant juvenile status, the Court of Appeals concluded that returning the minor to the custody of a mother who inadequately cared for and supervised him could not be a reunification that was viable.

• •

The application process for special immigrant juvenile (SIJ) status is set forth in the Federal Immigration and Nationality Act and involves two primary steps. First, the child, or someone acting on the child’s behalf, must obtain a predicate order from a state juvenile court that includes certain factual findings regarding the child’s eligibility for SIJ status. Without that order, a child cannot apply for SIJ classification. Second, the child, or any person acting on the child’s behalf, 8 C.F.R. § 204.11(b), must submit a petition, along with the predicate order and other supporting documents, to the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) for review and approval. If USCIS approves the petition, the child is then eligible to apply for adjustment of status to a lawful permanent resident under 8 U.S.C.S. § 1255 Go To Headnote

Federal regulations define juvenile courts as courts having jurisdiction under state law to make judicial determinations about the custody and care of juveniles. 8 C.F.R. § 204.11(a). Maryland law designates circuit courts as having such jurisdiction and, consequently, authority to preside over special immigrant juvenile status proceedings. Md. Code Ann., Fam. Law § 1-201(b)(10) (2012, 2018 Supp.). Go To Headnote Family Law: Guardians

Gonzalez v. State (In re Carlos D.), 300 Neb. 646, 915 N.W.2d 581, 2018 Neb. LEXIS 135 (Neb. 2018)

Overview: A county court erred in finding it could not make findings required to seek special immigrant juvenile status under 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J) because, having granted guardianship of the subject child, it was, pursuant to amended Neb. Rev. Stat. § 43-1238(b) (Reissue 2016), a “juvenile court” authorized to make such findings.

In order to achieve special immigrant juvenile status, an individual whose custody has been determined prior to age 21, 8 C.F.R. § 204.11 (2018), must also obtain the judicial determinations listed in 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(i) and (ii) from a “juvenile court,” as that term is used in the federal provisions. The Code of Federal Regulations defines “juvenile court” as a court located in the United States having jurisdiction under state law to make judicial determinations about the custody and care of juveniles. 8 C.F.R. § 204.11(a). A guardianship of a child is a child custody determination, and thus, a county court is considered a “juvenile court” for purposes of 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(i) and (ii). A guardianship over a juvenile renders the juvenile subject to 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(i) Go To Headnote

Governments: Courts: Authority to Adjudicate

Alberto v. State (In re Luis J.), 300 Neb. 659, 915 N.W.2d 589, 2018 Neb. LEXIS 136 (Neb. 2018).

Overview: A county court erred in finding it was not a juvenile court authorized to make findings needed for a child to seek special juvenile immigrant status under 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J), because, under amended Neb. Rev. Stat. § 43-1238(b) (Reissue 2016), having awarded guardianship of the child, it had jurisdiction to make such findings.

In order to achieve special immigrant juvenile status, an individual whose custody has been determined prior to age 21, 8 C.F.R. § 204.11, must have obtained the judicial determinations listed in 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(i) and (ii) from a “juvenile court,” as that term is used in the federal provisions. The Code of Federal Regulations defines “juvenile court” as a court located in the United States having jurisdiction under state law to make judicial determinations

Immigration Law: Adjustment of Status: Administrative Proceedings

Budhathoki v. Nielsen, 898 F.3d 504, 2018 U.S. App. LEXIS 21377 (5th Cir. 2018)

Overview: The agency properly considered the effect of the state court order under Tex. Fam. Code Ann. § 101.032 of Suits Affecting Parent-Child Relationship (SAPCR) because the agency had an obligation to review the SAPCR order, which was for child support, and consider its impact on the petitioner’s applications for Special Immigrant Juvenile (SIJ) status.

•

•

Special Immigrant Juvenile (SIJ) status is available to an immigrant who is present in the United States — (i) who has been declared dependent on a juvenile court located in the United States or whom such a court has legally committed to, or placed under the custody of, an agency or department of a State, or an individual or entity appointed by a State or juvenile court located in the United States, and whose reunification with 1 or both of the immigrant’s parents is not viable due to abuse, neglect, abandonment, or a similar basis found under State law 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J). By regulation, a juvenile court is a court located in the United States having jurisdiction under State law to make judicial determinations about the custody and care of juveniles. 8 C.F.R. § 204.11(a). Once the applicant has the necessary predicate order, he must submit his application to the agency, attaching the state court order 8 C.F.R. § 204.11(d). The petitioner bears the burden of establishing eligibility. 8 U.S.C.S. § 1361. A successful application also requires the consent of the Secretary of Homeland Security to the grant of the SIJ status, which can be given through directors of U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Service. 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(iii) Go To Headnote

The agency obligation to review state court orders for their sufficiency is the approach of the regulations identifying the documents that must be submitted in support of Special Immigrant Juvenile (SIJ) status: (2) One or more documents which include: (i) A juvenile court order, issued by a court of competent jurisdiction located in the United States, showing that the court has found the beneficiary to be dependent upon that court; (ii) A juvenile court order, issued by a court of competent jurisdiction located in the United States, showing that the court has found the beneficiary eligible for long-term foster care; and (iii) Evidence of a determination made in judicial or administrative proceedings by a court or agency recognized by the juvenile court and authorized by law to make such decisions, that it would not be in the beneficiary’s best interest to be returned to the country of nationality or last habitual residence of the beneficiary or of his or her parent or parents. 8 C.F.R. § 204.11(d) Go To Headnote

Pierre v. McElroy, 200 F. Supp. 2d 251, 2001 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 19982 (S.D.N.Y. 2001)

Overview: PATRIOT Act gave immigrant right not to age out due to terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, and INS was required to perform its duty to do requisite investigation and adjudication of I-360 petitions brought before September 11, 2001.

• about the custody and care of juveniles. 8 C.F.R. § 204.11(a). A Nebraska county court which properly appoints a guardian for a juvenile makes a custody determination, and thus, a county court is considered a “juvenile court” for purposes of 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(i) and (ii). A guardianship over a juvenile renders the juvenile subject to 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(i) Go To Headnote

To be eligible for Special Immigrant Juvenile Status under 8 C.F.R. § 204.11(c), the petitioner must be under 21 years of age, single, and must have been declared dependant upon a juvenile court. In addition, the petitioner must be found eligible for long-term foster care, and a court must have found that it would not be in the petitioner’s best interest to be returned to the country of nationality or last habitual residence of the beneficiary or his or her parent or parents.

Go To Headnote

Alberto v. State (In re Luis J.), 300 Neb. 659, 915 N.W.2d 589, 2018 Neb. LEXIS 136 (Neb. 2018).

Overview: A county court erred in finding it was not a juvenile court authorized to make findings needed for a child to seek special juvenile immigrant status under 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J), because, under amended Neb. Rev. Stat. § 43-1238(b) (Reissue 2016), having awarded guardianship of the child, it had jurisdiction to make such findings.

•

In order to achieve special immigrant juvenile status, an individual whose custody has been determined prior to age 21, 8 C.F.R. § 204.11, must have obtained the judicial determinations listed in 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(i) and (ii) from a “juvenile court,” as that term is used in the federal provisions. The Code of Federal Regulations defines “juvenile court” as a court located in the United States having jurisdiction under state law to make judicial determinations about the custody and care of juveniles. 8 C.F.R. § 204.11(a). A Nebraska county court which properly appoints a guardian for a juvenile makes a custody determination, and thus, a county court is considered a “juvenile court” for purposes of 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(i) and (ii). A guardianship over a juvenile renders the juvenile subject to 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(i). Go

To Headnote

Gonzalez v. State (In re Carlos D.), 300 Neb. 646, 915 N.W.2d 581, 2018 Neb. LEXIS 135 (Neb 2018)

Overview: A county court erred in finding it could not make findings required to seek special immigrant juvenile status under 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J) because, having granted guardianship of the subject child, it was, pursuant to amended Neb. Rev. Stat. § 43-1238(b) (Reissue 2016), a “juvenile court” authorized to make such findings.

•

In order to achieve special immigrant juvenile status, an individual whose custody has been determined prior to age 21, 8 C.F.R. § 204.11 (2018), must also obtain the judicial determinations listed in 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(i) and (ii) from a “juvenile court,” as that term is used in the federal provisions. The Code of Federal Regulations defines “juvenile court” as a court located in the United States having jurisdiction under state law to make judicial determinations about the custody and care of juveniles. 8 C.F.R. § 204.11(a). A guardianship of a child is a child custody determination, and thus, a county court is considered a “juvenile court” for purposes of 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(i) and (ii). A guardianship over a juvenile renders the juvenile subject to 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(i) Go To Headnote

Immigration Law: Deportation & Removal: Relief: Suspension of Deportation

Alberto v. State (In re Luis J.), 300 Neb. 659, 915 N.W.2d 589, 2018 Neb. LEXIS 136 (Neb. 2018)

Overview: A county court erred in finding it was not a juvenile court authorized to make findings needed for a child to seek special juvenile immigrant status under 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J), because, under amended Neb. Rev. Stat. § 43-1238(b) (Reissue 2016), having awarded guardianship of the child, it had jurisdiction to make such findings.

•

In order to achieve special immigrant juvenile status, an individual whose custody has been determined prior to age 21, 8 C.F.R. § 204.11, must have obtained the judicial determinations listed in 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(i) and (ii) from a “juvenile court,” as that term is used in the federal provisions. The Code of Federal Regulations defines “juvenile court” as a court located in the United States having jurisdiction under state law to make judicial determinations about the custody and care of juveniles. 8 C.F.R. § 204.11(a). A Nebraska county court which properly appoints a guardian for a juvenile makes a custody determination, and thus, a county court is considered a “juvenile court” for purposes of 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(i) and (ii). A

guardianship over a juvenile renders the juvenile subject to 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(i) Go To Headnote

Gonzalez v. State (In re Carlos D.), 300 Neb. 646, 915 N.W.2d 581, 2018 Neb. LEXIS 135 (Neb. 2018)

Overview: A county court erred in finding it could not make findings required to seek special immigrant juvenile status under 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J) because, having granted guardianship of the subject child, it was, pursuant to amended Neb. Rev. Stat. § 43-1238(b) (Reissue 2016), a “juvenile court” authorized to make such findings.

In order to achieve special immigrant juvenile status, an individual whose custody has been determined prior to age 21, 8 C.F.R. § 204.11 (2018), must also obtain the judicial determinations listed in 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(i) and (ii) from a “juvenile court,” as that term is used in the federal provisions. The Code of Federal Regulations defines “juvenile court” as a court located in the United States having jurisdiction under state law to make judicial determinations about the custody and care of juveniles. 8 C.F.R. § 204.11(a). A guardianship of a child is a child custody determination, and thus, a county court is considered a “juvenile court” for purposes of 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(i) and (ii). A guardianship over a juvenile renders the juvenile subject to 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(i) Go To Headnote

Osorio-Martinez v. AG United States, 893 F.3d 153, 2018 U.S. App. LEXIS 16265 (3d Cir. 2018).

Overview: The jurisdiction-stripping provision of the Immigration and Nationality Act, 8 U.S.C.S. § 1252, operated as an unconstitutional suspension of the writ of habeas corpus as applied to special immigrant juvenile designees seeking judicial review of orders of expedited removal.

The text of the Immigration and Nationality Act explicitly designates special immigrant juvenile as a status that affords its designees a host of legal rights and protections. 8 U.S.C.S. §§ 1101(a)(27)(J)(iii), 1255(h); 8 C.F.R. § 204.11(b). Go To Headnote

Alien children may receive special immigrant juvenile status only after satisfying a set of rigorous, congressionally defined eligibility criteria, including that a juvenile court find it would not be in the child’s best interest to return to her country of last habitual residence and that the child is dependent on the court or placed in the custody of the state or someone appointed by the state. 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J); 8 C.F.R. § 204.11(c). The child must also receive approval from the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services and the consent of the United States Secretary of Homeland Security to obtain the status. 8 U.S.C.S.§ 1101(a)(27)(J) Go To Headnote

Immigration Law: Immigrants

Budhathoki v. Nielsen, 898 F.3d 504, 2018 U.S. App. LEXIS 21377 (5th Cir. 2018)

Overview: The agency properly considered the effect of the state court order under Tex. Fam. Code Ann. § 101.032 of Suits Affecting Parent-Child Relationship (SAPCR) because the agency had an obligation to review the SAPCR order, which was for child support, and consider its impact on the petitioner’s applications for Special Immigrant Juvenile (SIJ) status.

Special Immigrant Juvenile (SIJ) status is available to an immigrant who is present in the United States — (i) who has been declared dependent on a juvenile court located in the United States or whom such a court has legally committed to, or placed under the custody of, an agency or department of a State, or an individual or entity appointed by a State or juvenile court located in the United States, and whose reunification with 1 or both of the immigrant’s parents is not viable due to abuse, neglect, abandonment, or a similar basis found under State law 8 U.S.C.S. §

Immigration Law: Immigrants: Special Immigrants

Amaya v. Rivera, 135 Nev. 208, 444 P.3d 450, 2019 Nev. LEXIS 37 (Nev. 2019)

Overview: In a case in which district court denied mother’s motion to make the three predicate findings necessary to petition the federal government for special immigrant juvenile (SIJ) status, district court erred when it declined to consider whether reunification with child’s father was viable after concluding that reunification with mother was viable.

•

Federal law provides a pathway for undocumented juveniles residing in the United States to acquire lawful permanent residency by obtaining special immigrant juvenile (SIJ) status under 8 U.S.C.S. ? 1101(a)(27)(J). 8 C.F.R. ? 204.11 (2018). Obtaining SIJ status is a two-step process implicating both state and federal law: first, the applicant must go to state court to obtain a juvenile court order issuing predicate findings, and only after such findings are made can the applicant petition the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) for SIJ status. The state trial court does not determine whether a petitioner qualifies for SIJ status, but rather provides an evidentiary record for USCIS to review in considering an applicant’s petition. Go To Headnote

Romero v. Perez, 463 Md. 182, 205 A.3d 903, 2019 Md. LEXIS 163 (2019)

Overview: In a case involving whether an undocumented minor was eligible for special immigrant juvenile status, the Court of Appeals concluded that returning the minor to the custody of a mother who inadequately cared for and supervised him could not be a reunification that was viable.

•

• 1101(a)(27)(J). By regulation, a juvenile court is a court located in the United States having jurisdiction under State law to make judicial determinations about the custody and care of juveniles. 8 C.F.R. § 204.11(a). Once the applicant has the necessary predicate order, he must submit his application to the agency, attaching the state court order 8 C.F.R. § 204.11(d). The petitioner bears the burden of establishing eligibility. 8 U.S.C.S. § 1361. A successful application also requires the consent of the Secretary of Homeland Security to the grant of the SIJ status, which can be given through directors of U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Service. 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(iii) Go To Headnote

The application process for special immigrant juvenile (SIJ) status is set forth in the Federal Immigration and Nationality Act and involves two primary steps. First, the child, or someone acting on the child’s behalf, must obtain a predicate order from a state juvenile court that includes certain factual findings regarding the child’s eligibility for SIJ status. Without that order, a child cannot apply for SIJ classification. Second, the child, or any person acting on the child’s behalf, 8 C.F.R. § 204.11(b), must submit a petition, along with the predicate order and other supporting documents, to the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) for review and approval. If USCIS approves the petition, the child is then eligible to apply for adjustment of status to a lawful permanent resident under 8 U.S.C.S. § 1255. Go To Headnote

Federal regulations define juvenile courts as courts having jurisdiction under state law to make judicial determinations about the custody and care of juveniles. 8 C.F.R. § 204.11(a). Maryland law designates circuit courts as having such jurisdiction and, consequently, authority to preside over special immigrant juvenile status proceedings. Md. Code Ann., Fam. Law § 1-201(b)(10) (2012, 2018 Supp.). Go To Headnote

Osorio-Martinez v. AG United States, 893 F.3d 153, 2018 U.S. App. LEXIS 16265 (3d Cir. 2018).

Overview: The jurisdiction-stripping provision of the Immigration and Nationality Act, 8 U.S.C.S. § 1252, operated as an unconstitutional suspension of the writ of habeas corpus as applied to special immigrant juvenile designees seeking judicial review of orders of expedited removal.

•

•

•

Alien children may receive special immigrant juvenile status only after satisfying a set of rigorous, congressionally defined eligibility criteria, including that a juvenile court find it would not be in the child’s best interest to return to her country of last habitual residence and that the child is dependent on the court or placed in the custody of the state or someone appointed by the state. 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J); 8 C.F.R. § 204.11(c). The child must also receive approval from the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services and the consent of the United States Secretary of Homeland Security to obtain the status. 8 U.S.C.S.§ 1101(a)(27)(J). Go To Headnote

To qualify for special immigrant juvenile status, applicants not only must be physically present in the United States, unmarried, and under the age of 21, but also, before applying to the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, they must obtain an order of dependency from a state juvenile court. 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(i); 8 C.F.R. § 204.11(c). That order requires the state court to find: (1) that the applicant is dependent on a juvenile court or placed under the custody of a state agency or someone appointed by the state; (2) that it would not be in the alien’s best interest to be returned to the alien’s or parent’s previous country of nationality or habitual residence,; and (3) that reunification with one or both of the immigrant’s parents is not viable due to abuse, neglect, abandonment, or a similar basis found under state law. 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(i). Moreover, these determinations must be in accordance with state law governing such declarations of dependency, 8 C.F.R. § 204.11(c)(3), which, depending on the state, may also entail specific residency requirements. Go To Headnote

J.U. v. J.C.P.C., 176 A.3d 136, 2018 D.C. App. LEXIS 2 (D.C. 2018)

M.B. v. Quarantillo, 301 F.3d 109, 2002 U.S. App. LEXIS 17412 (3d Cir. 2002).

Pierre v. McElroy, 200 F. Supp. 2d 251, 2001 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 19982 (S.D.N.Y. 2001).

Overview: PATRIOT Act gave immigrant right not to age out due to terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, and INS was required to perform its duty to do requisite investigation and adjudication of I-360 petitions brought before September 11, 2001.

•

To be eligible for Special Immigrant Juvenile Status under 8 C.F.R. § 204.11(c), the petitioner must be under 21 years of age, single, and must have been declared dependant upon a juvenile court. In addition, the petitioner must be found eligible for long-term foster care, and a court must have found that it would not be in the petitioner’s best interest to be returned to the country of nationality or last habitual residence of the beneficiary or his or her parent or parents. Go To Headnote

In re Tomas J , 318 Neb. 503, 18 N.W.3d 87, 2025 Neb. LEXIS 15 (Neb. 2025)

Overview: The court reasoned that because Tomas was 18 years old when the minor guardianship petition was filed, he was no longer considered a "child" under the UCCJEA. Therefore, the county court's jurisdiction was not governed by the UCCJEA.

• The text of the Immigration and Nationality Act explicitly designates special immigrant juvenile as a status that affords its designees a host of legal rights and protections. 8 U.S.C.S. §§ 1101(a)(27)(J)(iii), 1255(h); 8 C.F.R. § 204.11(b). Go To Headnote

Under federal immigration law, factual findings to support Special Immigrant Juvenile (SIJ) status must be made by a state court that has entered an order either declaring the immigrant to be dependent on the court or placing the immigrant in the custody of an agency or department of the state or an individual or entity appointed by the court. 8 U.S.C.S. § 1101(a) (27)(J)(i). 8 C.F.R. § 204.11(c)(1)(i)(B).Go To Headnote

Hierarchy Notes:

8 CFR Ch. I

8 CFR Ch. I, Subch. B, Pt. 204

LEXISNEXIS’ CODE OF FEDERAL REGULATIONS

Copyright © 2025 All rights reserved.

Administrative Office of the Co u rts

Michael J. Blee , J .A.D.

Act ing Admin ist rative D ir ector of t he Court s

Ric h ard J. Hughes Justice Complex • P.O. Box 037 Trenton , NJ 08625-0037 ° njcourts .gov • Te l: 609 - 376 -3000 • Fax: 609-376-3002

To: Assignment Judges Trial Court Administrators

From: Michael J. Blee, J.A.D.~f

Re:

DIRECTIVE# 04-25

Que stion s may b e di re cted to the Famil y Pract ice D ivision at 609-815-2900 , ext. 55350

Date: Family - Special Immigrant Juvenile Status (SIJS) Filing Requirements

August 13, 2025

This Directive is to clarify the filing requirements for complaints filed in the Superior Court for parties seeking a "predicate" order for Special Immigrant Juvenile Status (SIJS).

Federal immigration law affords protections for abused , neglected , or abandoned children who wish to apply for lawful , permanent resident status in the United States. These children may be eligible for classification as a " special immigrant juvenile," which permits them to remain legally in the United States.

The two-step SIJS process involves both state and federal systems. It begins with an application in a state comt requesting the entry of a " predicate " order, which requires the court to make the following findings:

1. The juvenile is under the age of 21 at the time the complaint is filed and is unman-ied;

2. The juvenile is dependent on the court or has been placed under the custody of an agency or an indiv idual appointed by the court;

3. The comt has jurisdiction under State law to make judicial determinations about the custody and care of the juvenile;

4. Reunification with one or both juvenile's parents is not viable due to abuse , neglect , or abandomnent or a similar basis under State law; and

5. It is not in the "best interest" of the juvenile to be returned to the parent's previous

Directive# 04-25-Family -Special ImmigrantJuvenile Status (SIJS) Filing Requirements

August 13, 2025

Page 2 of3

countryofnationalityorcountryoflasthabitualresidence.

The state'spredicate order isnot animmigration determination. Itis a prerequisite that mustbe fulfilledpriortothesecondstepoftheprocess, whichis thesubmission ofaSUS application totheUnited States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS)intheforofan 1-360petition. Thepredicate order is to be included withthe SUSapplication. IftheUSCIS approves the 1-360 petition, thejuvenileisgrantedSUS.

Requests forthe SUS predicateordershouldbefiledintheSuperiorCourt, FamilyPart. The form, "Verified Complaint forSpecialImmigrant JuvenileStatus PredicateOrder" (CN 13321)was createdfor self-representedlitigants and is available online at Forms/13321. The form whencompleted sets forth the minimum statutorily requiredinformationthatmust be submitted as part ofthe complaint fora SUSpredicateorder. Thecourt, inits discretion, may requireadditionalinformation itdeemsnecessarytomake the predicateSIJS findings.

Acomplaint for a SUSpredicateordermay be filedby any ofthe following:

1. Theparentorguardianofthe minorchild.

2. A lawguardianortheDivisionofChild Protection&Permanency (DCPP)ifthereis an openFNor FGcase.

3. The child, iftheyare 18 yearsofageorolder.

4. Thechild, ifthey areunderthe ageof18 and do not haveaparent orguardian.

Generally, requests for aSUSpredicateorder shall be filedin the non-dissolution (FD) docketexceptasset forthbelow(basedonanyexistingFamilycase). For complaints filed in theFDdocket, aseparatecomplaint shall be filed foreachchild. Ifthereismorethanonechild seeking SUSunderanactive/openFN, FGorFM matter, aseparatepredicateorder foreach child shallbeentered.

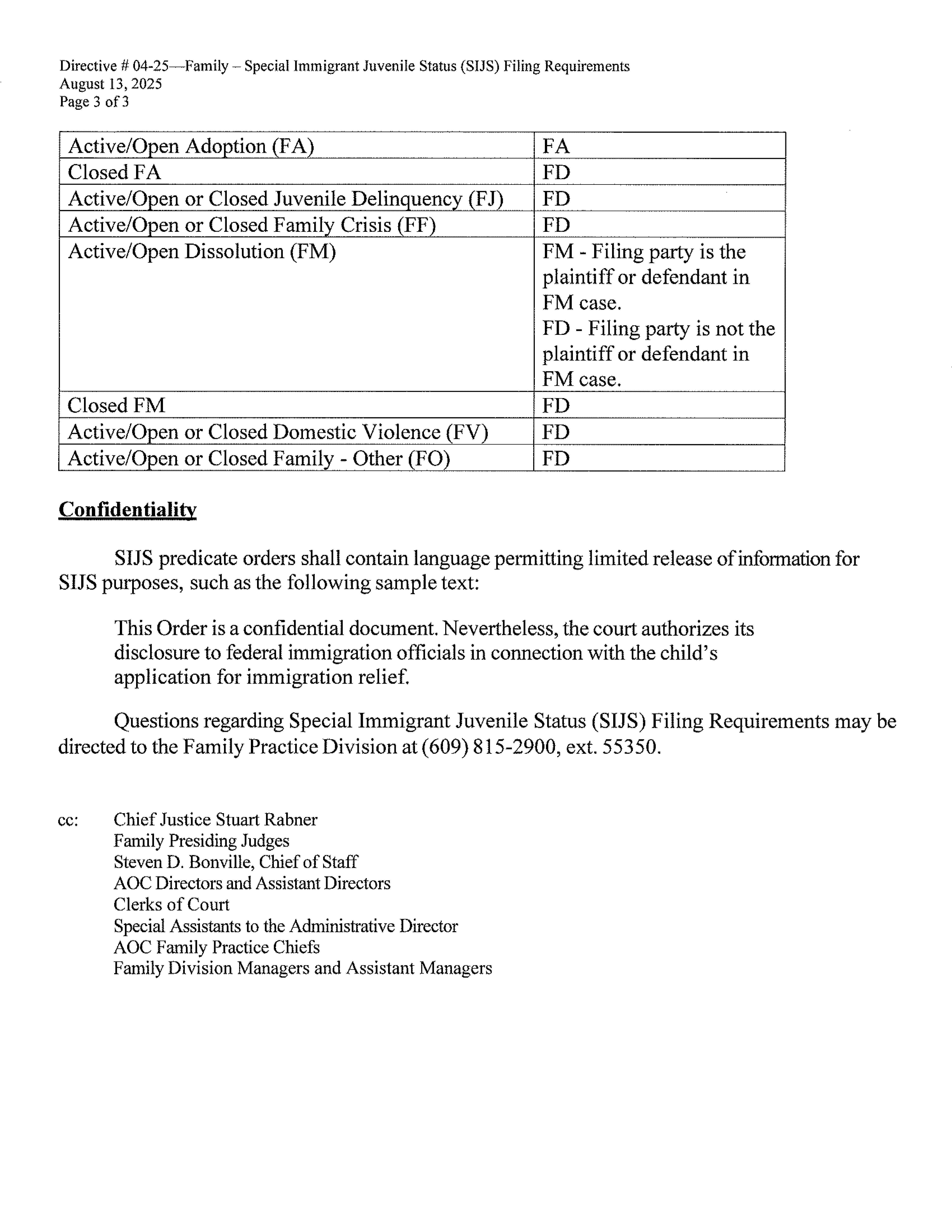

Existing Family Case Filing Docket

None Non-Dissolution (FD)

Active/Open ChildProtection (FN) FN

ClosedFN FD

Active/Open TerminationofParental Rights (FG) FG

ClosedFG FD

Active/Open KinshipLegal Guardianship (FL) FL

ClosedFL FD

Active/Open or Closed Child Placement (FC) FD

Directive # 04-25~Family Special Immigrant Juvenile Status (SIJS) Filing Requirements

August 13, 2025

Page 3 of3

Active/Open Adoption (FA) FA

Closed FA FD

Active/Open or Closed Juvenile Delinquency (FJ) FD

Active/Open or Closed Family Crisis (FF) FD

Active/Open Dissolution (FM)

FM - Filing party is the plaintiff or defendant in FM case.

FD - Filing party is not the plaintiff or defendant in FM case.

Closed FM FD

Active/Open or Closed Domestic Violence (FV) FD

Active/Open or Closed Family - Other (FO) FD

SIJS predicate orders shall contain language petmitting limited release ofinformation for SUS purposes, such as the following sample text:

This Order is a confidential document. Nevertheless, the court authorizes its disclosure to federal immigration officials in connection with the child's application for immigration relief.

Questions regarding Special Immigrant Juvenile Status (SUS) Filing Requirements may be directed to the Family Practice Division at (609) 815-2900, ext. 55350.

cc: Chief Justice Stuart Rabner

Family Presiding Judges

Steven D. Bonville, Chief of Staff

AOC Directors and Assistant Directors

Clerks of Court

Special Assistants to the Administrative Director

AOC Family Practice Chiefs

Fan1ily Division Managers and Assistant Managers

U.S. Department of Homeland Security

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services

Office of the Director Camp Springs, MD 20588-0009

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services

June 6, 2025 PA-2025-07

SUBJECT: Special Immigrant Juvenile Classification and Deferred Action

Purpose

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) is issuing policy guidance in the USCIS Policy Manual to eliminate automatic consideration of deferred action (and related employment authorization) for aliens classified as Special Immigrant Juveniles (SIJs) who are ineligible to apply for adjustment of status to lawful permanent resident (LPR) status due to visa unavailability.

Background

The SIJ classification is available to alien children subject to state juvenile court proceedings related to abuse, neglect, abandonment, or a similar basis under state law. 1 SIJ classification does not render an alien lawfully present, does not confer lawful status, and does not result in eligibility to apply for employment authorization. An alien classified as an SIJ, however, may seek to adjust status to that of an LPR based on the SIJ classification if the alien meets certain requirements. One of the requirements is that an immigrant visa be immediately available at the time of filing the adjustment of status application. 2

On March 7, 2022, USCIS updated its policy guidance to provide that the agency will automatically consider granting deferred action on a case-by-case basis to aliens classified as SIJs who are ineligible to apply for adjustment of status solely due to unavailable immigrant visas. 3

While Congress likely did not envision that SIJ petitioners would have to wait years before a visa became available, Congress also did not expressly permit deferred action and related employment authorization for this population. Neither an alien having an approved Petition for Amerasian, Widow(er), or Special Immigrant (Form I-360) without an immediately available immigrant visa available nor a juvenile court determination relating to the best interest of the SIJ are sufficiently compelling reasons, supported by any existing statute or regulation, to continue to provide a deferred action process for this immigrant category.

Therefore, USCIS has determined that this update is necessary to more closely align agency policies and procedures with statutory requirements and authorities. Further, this policy adheres to Executive

1 See INA 101(a)(27)(J). See 8 CFR 204.11

2 See INA 245(a) and INA 245(h). See 8 CFR 245.2(a)(2)(i)(A)

3 See Special Immigrant Juvenile Classification and Deferred Action, PA-2022-10, issued March 7, 2022.

PA-2025-07: Special Immigrant Juvenile Classification and Deferred Action Page: 2

Order 14161, “Protecting the United States From Foreign Terrorists and Other National Security and Public Safety Threats” (January 20, 2025) 4 and USCIS has determined it is in the national and public interest to revert to the policy prior to March 7, 2022.

This guidance confirms that USCIS will no longer consider granting deferred action on a case-bycase basis to aliens classified as SIJs who are ineligible to apply for adjustment of status solely due to unavailable immigrant visas. This update, contained in Volume 6 of the Policy Manual, is effective immediately and applies to aliens classified as SIJs before, on, or after that date based on an approved Form I-360. The guidance contained in the Policy Manual is controlling and supersedes any related prior guidance.

• Provides that USCIS will no longer conduct deferred action determinations for aliens with SIJ classification who cannot apply for adjustment of status solely because an immigrant visa is not immediately available.

• Removes prior guidance stating USCIS will accept new Applications for Employment Authorization (Form I-765), under category (c)(14), from aliens with SIJ classification who have been granted deferred action by USCIS because they cannot apply for adjustment of status solely because an immigrant visa number is not immediately available

• Explains that aliens with current deferred action based on their SIJ classification will generally retain this deferred action, as well as retain their current employment authorization provided based on this deferred action, until the current validity periods expire.

• Provides minor clarifications to the current policy on terminating SIJ deferred action and confirms that USCIS, within its discretion, may terminate deferred action and revoke any associated employment authorization prior to the end of the current validity period.

Affected Section: Volume 6 > Part J > Chapter 4, Adjudication

• Revises Section G (Deferred Action) in its entirety.

USCIS may also make other minor technical, stylistic, and conforming changes consistent with this update.

Citation

Volume 6: Immigrants, Part J, Special Immigrant Juveniles, Chapter 4, Adjudication [6 USCIS-PM J.4].

4 This directs federal agencies to, in part, “vet and screen to the maximum degree possible all aliens who intend to be admitted, enter, or are already inside the United States.” This policy promotes this by ensuring that USCIS Fraud and National Security personnel, as well as adjudicating officers, are not unnecessarily restricted from considering potentially relevant information within a record.

Reporter

Supreme Court of New Jersey

April 14, 2015, Argued; August 26, 2015, Decided A-114 September Term 2013, A-117 September Term 2013, 074241 and 074527

223 N.J. 196 *; 121 A.3d 849 **; 2015 N.J. LEXIS 878 ***

H.S.P., PLAINTIFF APPELLANT, v. J.., DEFENDANT.K.G.,PLAINTIFF APPELLANT, v. M.S. (DECEASED), DEFENDANT.IN THE MATTEROF J.S.G.ANDK.S.G. (MINORS).

Prior History: H.S.P. v. J.K., 435 N.J. Super. 147, 87 A.3d255,2014N.J. Super. LEXIS 42 (App.Div., 2014)

(This syllabus is not part of the opinion of the Court. It has been prepared by the Office of the Clerk for the convenience of the reader. It has been neither reviewed nor approvedby the Supreme Court. Please note that, in the interest of brevity, portions of any opinion may not have been summarized.)

H.S.P. v. J.K. (A-114-13) (074241)

K.G. v. M.S. (Deceased) (A-117-13) (074527)

Argued April14, 2015 -- Decided August 26, 2015

CUFF,P.J.A.D.(temporarily assigned), writing for a unanimous Court. &

In these appeals, the Court examines the role of New Jersey state courts, pursuant to 8 U.S... 1101(a)(27)(J) and its implementing regulation, 8 C.F.R. § 204.11, in making the predicate findings necessary for a non-citizen child to apply for "special immigrant juvenile" (SIJ) status, which is a form of immigration relief permitting alien children to obtain lawful permanent residency and, eventually, citizenship, under the Immigration Act of1990, as amended by the William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008 (TVPRA).

M.S., who was born in India in 1994,entered the United States without proper documentation in July 2011. In India, M.S. resided with his mother, J.K., after the family was abandoned by M.S.'s father when M.S. was four years old. When M.S. was fifteen, J.K.becameill and

could no longer work. M.S. took a job as a construction worker, working approximately seventy-five hours per week and developing a skin condition and back problems. Fearing that M.S. would die if he remained in India,J.K. arranged for him to travel to the United State to live with her brother, petitioner H.S.P. Sincearriving in the United States, M.S. has remained in close contact with his mother via weekly telephone calls.

In May 2012, H.S.P. filed a petition in the Family Part requesting that he be granted custody of M.S. and that the court issue a predicateorder, pursuant to 8 U.S.C.A. § 1101(a)(27)(J) and its implementing regulation, 8 C.F.R. § 204.11, finding that M.S. meets thestatutory requirements to be a special immigrant juvenile. Specifically, H.S.P. asked that, under the statute, the court find that reunification with "1 or both" of M.S.'s parents was not viable due to abuse, neglect, or abandonment and that returning to India would not be in M.S's bestinterests, allowing M.S. to then apply to the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) for SIJ status. Although the court awarded temporary custody to H.S.P., it did not find that either of M.S.'s parents had willfully abandoned him and, consequently, did not reach the question ofhis best interests. H.S.P. appealed, and, in a published decision, the Appellate Division affirmed. H.S.P. v. J.K., 435 N.J. Super. 147, 87 A.3d 255 (App. Div. 2013). The panel agreed that M.S. was not abandoned or neglected by J.K because, although permitting a child to be employed in a dangerous activity constitutes abuse under New Jersey law, it did not contravene the laws of India.The panel also affirmed the trial court's refusal to make a best interests finding. This Court granted H.S.P.'s petition for certification. 218 N.J. 532, 95 A.3d 258 (2014).

J.S.G., born in 1998, and K.S.G., born in2001, are the biological daughters of K.G. (their mother) and M.S. (their father), natives of El Salvador.After separating from M.S. in 2008, K.G. came to the United States, although she remained in near-daily contact with her daughters and sent money for their support. M.S. was murdered in 2013, and the children were cared for by

223 N.J. 196, *196; 121 A.3d 849, **849;2015N.J. LEXIS 878, ***878

M.S.'s mother, who K.G. believed may have been physically abusing the girls. Shortly after M.S.'s death, a threat was made on hismother'slife, as well as the lives of J.S.G. and K.S.G. K.G. arranged for her daughters to come to theUnitedStates,but they were apprehended by immigration enforcement agents when crossing at the United States-Mexican border. Removal proceedings commenced, although the girls ultimately went to live with their mother in Elizabeth. In March 2014, K.G. filed a complaint in the Family Part seeking custody of her daughters and requesting that the court make the predicate findings to permit them to apply for SIJ status.

The court granted K.G.'s application for custody. Italso found that reunification with M.S. was not viable because he was deceased, and that it was not in the children's best interests to return to El Salvador because no family membercould care for them there. However, the court determined that reunification with K.G. was viable, and that there was no basis under state law to suggest she had abused, neglected, or abandoned her daughters. Based on thatdetermination, and in reliance on the Appellate Division's decision inH.S.P., the court denied the children's application for SIJ status. This Court granted K.G.'s motionfordirectcertification.220 N.J.493, 107 A.3d681 (2014).

HELD: When faced with a request for an SIJ predicate order, the Family Part's sole task is to apply New Jersey law to make factual findings with regard to each of the requirements list in 8 C.F.R. § 204.11. The Family Part does not have jurisdiction to grant or deny applications for immigration relief.

2. The legislative scheme relating to SIJ status demonstrates that the determination of whether a child should be classified as a specialimmigrant juvenile rests squarely with the federal government. Congress opted to rely on state courts as the appropriate forum for making initial factual findings because of their special expertise in making abuse and neglectdeterminations, evaluating the best interest factors, and ensuring appropriate custodial arrangements. However, there can be no legitimate argument that a New Jersey family court has jurisdiction to approve or deny a child's application for SIJ status. Rather, pursuant to theSIJ statute, a state court makes predicate factual findings relative to a juvenile's eligibility, and the juvenile then presents those findings to USCIS, which makes the ultimate decision as to whether or not the application for SIJ status should be granted. This comports with the well-established rule that the regulation of immigration is exclusively a federal power. (pp. 20-22)

3. The Family Part, when performing its closely circumscribedtask of making specified predicate factual findings, is required to apply New Jersey law, and not that of a foreign nation. This conclusion is supported by the plain language of 8 U.S.C.A. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(i), which requires a petitioner to show that reunification with "1 or bothofthe immigrant's parents is not viable due to abuse, neglect, abandonment, or a similarbasis under Statelaw." In light of the limited role played by the New Jersey Family Part in SIJ proceedings, the Court declines to interpret the "1 or both" language ofthe statute, finding that such a task is exclusively the province of the federal government. However, in order to ensure that factual findings issued by New Jersey courts provide USCIS with the information required to determine whether a given alien satisfies the eligibility criteria for SIJstatus, the Court instructs courts of the Family Part to make separate findings as to abuse, neglect, and abandonment with regard to both legal parents of an alien juvenile. Finally, the determination of

1. The1952Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), 8 U.S.C.A. §§ 1101-1537, is the cornerstone of United States immigration law and includes protections for abused, neglected, or abandoned childrenwho illegally entered the United States. In accordance with 8 U.S.C.A. § 1101(a)(27)(J), an undocumented minor immigrant is eligible for classification as a "special immigrant juvenile," which affords the minor relief from deportation and the opportunity to apply for permanent residency. The SIJ scheme was most recentlyamended in 2008 with the enactment of the TVPRA, which inserted language requiring that the child not be able to reunify with "1 or both" parents because of "abuse, neglect, abandonment, or a similar basis" under state law.8U.S.C.A. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(i). The current iteration of the statute also requires a finding that it would not be in the juvenile's best interest to be returned to his or her previous country of nationality. 8 U.S.C.A. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(ii). The processfor obtaining SIJ status is a unique, two-step, hybrid procedure involving both state and federal systems. Specifically, the child, or an individual acting on his or her behalf, must first petition a state juvenile court for an order making findings that the child satisfies certain criteria, including the requirements containedin8U.S.C.A. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(i) and (ii) and 8 C.F.R§ 204.11. This predicate order is not an immigration determination, but merely a prerequisite that must be fulfilled prior to the second step of the process, which is submission of the application for SIJ status to USCIS. (pp.16-20)

223 N.J. 196, *196; 121 A.3d 849,**849; 2015 N.J. LEXIS 878, ***878

whether an immigrant's purpose in applying for SIJ status matches with Congress's intent in creating that avenue of relief is properly left to the federal government. (pp. 22-25)

4.Whilereviewing courts give deference to a trial court's factual findings, no deference is owed to legal conclusions drawn by the trial court. With respect to the specific facts of H.S.P., the Court reverses and remands that aspect of the Appellate Division judgment finding that M.S.'s employment did not constitute abuse or neglect because H.S.P. failed to demonstrate that it was contrary to the laws of India. The Family Part is instructed to conduct an analysis, under New Jersey law, of whether reunification with each of M.S.'s legal parents is viable due to abuse, neglect or abandonment, in addition to making the other required findings under C.F.R.§ 204.11. With respect to K.G., the Court concludes that the trial court's factual determinations were supported by competent, credible evidence. However, the trial court erred in purporting to deny K.S.G.'s and J.S.G.'s applications for SIJ status. That determination is reversed and remanded, with instructions to the Family Part to make findings regarding each element of 8 C.F.R § 204.11, mindful that its sole purpose is to make those factual findings and not to adjudicate the children's applications for SIJ status. (pp. 26-28)

The judgment of the Appellate Division in H.S.P. is REVERSED and the matter is REMANDED to the Family Part for a new hearing conducted in accordance with this decision.The judgment of the trial court in K.G. is likewise REVERSED and REMANDED.

Counsel: [***1] H.S.P. v. J.K. (A-114-13): On certification to the Superior Court, Appellate Division, whose opinion is reported at 435 N.J. Super. 147, 87 A.3d 255 (App.Div.2014).

K.G. v. M.S.(A-117-13): On appeal from the Superior Court, Chancery Division, Union County.

Francis X. Geier argued the cause for appellant in H.S.P. v. J.K. (Basaran Law Office, attorneys; Mr. Geier and Melinda M. Basaran on the brief).

Kevin B. Kelly, Solangel Maldonado, Jessica Miles, Kimberly M. Mutcherson, Lori A. Nessel, Meredith Schalick, Sandra Simkins, and Carol A. Wood in H.S.P v. J.K. (Ms.Mandelbaum, Ms. Gottesman, Ms. Schalick, and Sarah Koloski Regina on the brief).

Randi S. Mandelbaum argued the cause for amici curiae

Ms. Mandelbaum, Farrin Anello, Jenny-Brooke Condon, Anne E. Freedman, Joanne Gottesman,AnjumGupta,

A. Matthew Boxer argued the cause for amici curiae American Friends Service Committee, Kids in Need of Defense, and The Young Center for Immigrant Children's Rights inH.S.P. v. J.K. (Lowenstein Sandler, attorneys; Mr. Boxer, Catherine Weiss, Eric Jesse, and Kathryn S. Pearson on the brief).

Randi S. Mandelbaum argued the cause for appellant in K.G. v. M.S. (Ms.Mandelbaum and Sarah Koloski Regina on the brief).

Judges: JUSTICES LaVECCHIA, ALBIN, PATTERSON, [***2] FERNANDEZ-VINAand SOLOMON join in JUDGE CUFF's opinion. CHIEF JUSTICE RABNER did not participate.

Opinion by: CUFF

[**851] [*199] JUDGE CUFF (temporarily assigned) delivered the opinion of the Court.

In this appeal, we examine the role of our state courts in making the predicate findings necessary for a noncitizen child to [*200] apply for "special immigrant juvenile" (SIJ) status under the Immigration [**852] Act of 1990, as amended by the William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008 (TVPRA), Pub. L. No. 110-457, 122 Stat. 5044. SIJ status is a form of immigration relief permitting alien children to obtain lawful permanent residency and, eventually, citizenship. To obtain SIJ status, a juvenile must complete a two-step process: first, the juvenile must apply to a state court for a predicate order finding that he or she meets the statutory requirements; second, he or she must submit a petition to United States Citizenship and ImmigrationServices (USCIS) demonstrating his or her statutory eligibility. 8C.F.R. § 204.111 detailsthe findings that must be made by a

1 The full citation for this regulation is: Special immigrant status for certain aliens declared dependent on a juvenile court

223 N.J. 196, *200; 121 A.3d849,**852; 2015 N.J. LEXIS 878, ***2

juvenile court before an alien's application for SIJ status will be considered by USCIS: in addition to a series of factual requirements, the [***3] juvenile must demonstratethat reunification with "1 or both" of his or her parents is not viable due to abuse, neglect, or abandonment. The court isthen required to determine whether it is in the juvenile's best interests to return to his or her home country.

The Family Part plays a critical role in a minor immigrant's attempt to obtain SIJ status but that role is closely circumscribed. The Family Part's sole task is to apply New Jersey law in order to make the child welfare findings required by 8 C.F.R. § 204.11. The Family Part does not have jurisdiction to grant or deny applications for immigration relief. That responsibility remains squarely in the hands of thefederal government. Nor does it have the jurisdiction to interpret federal immigration statutes. The Family Part's role in the SIJ process is solely to apply its expertise in family and child welfare matters to the issues raised in 8 C.F.R. § 204.11,regardless of its view as to the position likely to be taken [***4] by the federal agency or whether the minor has met the requirements [*201] for SIJ status. To that end,Family Part courts faced with a request for an SIJ predicate order should make factual findings with regard to each of the requirements listed in 8 C.F.R. § 204.11. When analyzing whether reunificationwith "1 or both" parents is not viable due to abuse, neglect, or abandonment, the Family Part shall make separate findings as to each parent, and that determination shall be made by applying the law of this state. Thisapproach will provide USCIS with sufficient information to enable it to determine whether SIJ status should be granted or denied, in accordance with the statutory interpretation of the SIJ provision applied by that agency.

Accordingly, we reverse the Appellate Division's decision in H.S.P. and the Family Part's decision in K.G. Both failed to address all of the requirements identified in 8 C.F.R. 204.11. The panel in H.S.P. also improperly applied the law of thechild'scountry of origin rather than the law of this state to address whether the juvenile had been abused, neglected, or abandoned in his or her home country. We remand both cases for further findings consistent with this opinion.

I. A. ***51

(special immigrant juvenile), 8 C.F.R. §204.11(2014). For the sake of brevity, we refer to this regulation as 8 C.F.R. § 204.11.

M.S., born in India on December 14, 1994, entered the United States without proper documentation in July 2011. Since then, he has resided with his uncle, petitioner H.S.P., and H.S.P.'s family in Passaic County. Prior to coming to the United States, M.S. resided with his mother, respondent [**853] J.K., and two older siblings. M.S.'s father abandoned the family when M.S. was four years old.M.S.'s siblings both died of unknown causes when each was seventeen years old. M.S. believes that theirdeathsresultedfrommalnourishment, unsanitary living conditions, the unavailability of medical care, and heart problems. When M.S. was fifteen, J.K. became ill and was unable to work. M.S.and J.K. moved in with J.K.'s mother, and M.S. stopped attending schooland took a job as [*202] a construction worker. M.S. worked approximately seventy-five hours a week at a construction site located more than two miles from the family home. The work causedM.S. to develop a skincondition and occasional back problems.

At some point, M.S. became ill. J.K. feared that he would die if he remained in India. She arranged for him to travel to the United States to live with her brother, H.S.P. M.S.entered the United States by [***6] walking across the United States-Mexico border in July 2011. Since arriving in the UnitedStates, M.S. has not had any health problems. He and J.K. remain in close contact via weekly telephone calls.

In May 2012, H.S.P. filed a petition in theFamilyPart requesting that he be granted custody of M.S. The petition identified J.K. as the respondent; however, in actuality, the two acted in concert to bring thepetition. H.S.P. also requested that the Family Part make the required findings to classify M.S. as a special immigrant juvenile under 8 U.S.C.A.§1101(a)(27)(J) and its implementing regulation, 8 C.F.R. § 204.11.

The Family Part conducted a custody hearing on September 27, 2012. The trial court awarded temporary custody of M.S. to H.S.P. Turning to the SIJ predicate findings, the court concluded that neither parent had "abandoned" M.S. It reasoned that "abandonment" required an affirmative act by a parent willfully forsaking the obligations owed to his or her child. The trial court credited testimony suggesting that M.S.'s father was an alcoholic or a drug addict, but determined that the evidence of record was insufficient to establish that he had willfully abandoned his son. Moreover,the trial court found [***7] that J.K. had not abandoned M.S. In contrast, J.K. remained actively involved in M.S.'s life. J.K.'s concern for M.S.'s best interests was evidenced by her decision to send M.S. to the United States and

223 N.J. 196,*202; 121 A.3d 849, **853;2015N.J. LEXIS 878, ***7

assistH.S.P.in attaining custody ofher son. Because it did not find that M.S. had been abandoned or neglected, the court did not reach the question of whether it would be in hisbest interests to remain in the UnitedStates or be returned to India.

[*203]

H.S.P. appealed. The Appellate Division affirmed the trial court's determinationthat M.S. was not abandoned or neglected by J.K., finding thatshe was financially unable to provide better care. H.S.P. v. J.K., 435 N.J. Super. 147, 159, 171, 87 A.3d 255 (App.Div.2013). The panelnoted that permitting a child to be employed in a dangerous activity constitutes abuse under New Jersey law, but found that petitioner failed to demonstrate that M.S.'s employment contravened the laws of India. Id. at 160, 87 A.3d 255. The panel reversed the trial court's finding with regard to abandonment by M.S.'s father, finding that a "total disregard of parental duties" was sufficient to constitute abandonment. Id. at 171, 87 A.3d 255. Despite that finding, the panel affirmed the trial court's refusal to make a best interests finding pursuant to 8 U.S.C.A. § 1101(a)(27)(J)(ii). lbid. The panel [***8] held that petitioner was not entitled to such a finding becausehe had not demonstrated that reunification with "neither" parent was viable due to abuse, [**854] neglect, or abandonment.Id. at 166,87A.3d255.

This Court granted H.S.P.'s petition for certification.218 N.J. 532, 95 A.3d 258 (2014). We also permitted the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), Kids in Need of Defense (KIND), the Young Center for Immigrant Children's Rights (YCICR), and, in their individual capacities, numerous New Jersey law school professors specializing in family and immigrationlaw, to appear as amici curiae.

B.

J.S.G., born December 1, 1998, and K.S.G., born April 30, 2001, are the biological daughters of K.G. (their mother) and M.S. (their father). K.G. and M.S., who are natives of El Salvador, married in 1998 and lived together in their home country for approximately ten years before separating. In January 2008, K.G. left El Salvador to come to the United States. J.S.G. and K.S.G. remained in El Salvador under the care of their father and his mother. After K.G.'s departure, she and her daughters remained in near-daily contact through telephone and video-conference calls. [*204] K.G. frequently sent money to M.S. for the care and support of J.S.G. and K.S.G. [***9]

M.S. was murdered by members of a local gang on April

13, 2013. His family believes that he was killed because he refused to pay a fee demanded by the gang. After his death, the children remained in the care of M.S.'s mother. At some point, during a video-conference with J.S.G. and K.S.G., K.G. observed bruises on K.S.G.'s face. This caused K.G. to believe that M.S.'s mother was physically abusing the girls. M.S.'s death was not the family's first interaction with gang violence. In summer 2012, when J.S.G. was twelve years old, she was raped by an acquaintance. Sheidentified him as a member of the "18"2 gang based on his piercings, tattoos, and hairstyle. At some point after the rape -which she did not reveal to her mother until after arriving in the United States -- J.S.G. attempted suicide.

Shortly after M.S.'s death, his mother received a telephone call, wherein the caller threatened to kill her, J.S.G., and K.S.G. [***10] if they did not leave their home. K.G. arranged for J.S.G. and K.S.G. to stay with her sister until she could save enough money to bring them to the United States. Their grandmother went to a son's house. The girls remainedwiththeirmaternal aunt for approximately twenty days, after whichthey began thejourney to the UnitedStates.

J.S.G. and K.S.G. entered the United States in June 2013 by crossing the United States-Mexico border. At that time, they were apprehended by immigration enforcement agents and removal proceedings were initiated. J.S.G. and K.S.G. were transferred to a shelter in Chicago, Illinois run by the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR). On July 27, 2013, ORR released both girls to K.G.'s care. They continue to reside at her home in Elizabeth. While in removal proceedings, both girls applied for SIJ status.

[*205] On March18,2014, K.G. filed a complaint in the Family Part seeking custody of J.S.G. and K.S.G.and requesting that the court make the predicate findings to permit them to apply for SIJ status. The Family Part conducted a hearing on April [**855] 28, 2014. After hearing testimony from K.G., J.S.G., and K.S.G., the court granted K.G.'s application for custody of her [***11] daughters.

Thetrial court then addressed the predicatefindings for SIJ status. The court determined that both girls were

2 This is apparently a shorthand reference to a group known as M-18, a transnational criminal organization considered a major threat to public security in El Salvador. U.S. Dept. of State, Bureau of Diplomatic Security, El Salvador2013Crime and SafetyReport 9 (2013).

223 N.J.196, *205; 121 A.3d 849, **855; 2015 N.J. LEXIS 878, ***11