I UNKNOWNS

INDUCTION

‘Do anything nice over Christmas?’

This time the assistant doesn’t answer at all. She just stops typing, dead in the middle of a word, and stares at Quinn.

Quinn says, ‘Did I ask you that already?’

‘Twice,’ the woman says. Exasperation and puzzlement. ‘We already had that whole conversation. And we also already had the conversation where I told you you already asked me that and you apologised.’

‘I’m sorry,’ Quinn says.

‘Yeah. That.’

‘You think I have memory issues,’ Quinn says. ‘You think I’ve got no long-term memory, and if I stay in one place for too long I forget why I’m there.’

The assistant, Rowland, says, cautiously, ‘I attributed it to stress.’

Quinn smiles sympathetically and shakes her head. ‘It’s not stress. Do you think Mr Mahlo’s going to be much longer?’

The assistant has turned back to her computer. ‘This is the

C-level. Meetings at this level take as long as they need to take, and you wait. Mr Mahlo will see you when he’s ready.’ She says this many times a day.

Quinn turns back to the window. The building is Georgian, with high ceilings, and the window is correspondingly tall, a rectangle of white. It is a stunning January day out there, brisk but clear and bright. Four floors below, the streets are rammed with traffic, like always. Beyond that, the river is busy too. Quinn watches a ferry.

She turns fifty this year. She is diminutive and flint-eyed, very dark-haired but rapidly greying. Today, her hair is strictly pulled back and up into a silver clasp. She wore her good suit for this, one button, very dark grey, with a solid blue blouse underneath. Ankle boots with stout heels, two silver stud earrings in each lobe. Contact lenses, not the usual glasses. On a lanyard around her neck she wears a security pass with a bright orange and red diagonal stripe.

She toys nervously with her lighter. She wastes a little of the flame. She is here to meet Mahlo, and the C-level is scary. Cs never want to see you for a small thing. It’s the end of the world, or nothing.

Something in her bag chimes. It’s time for a pill. She fishes her phone out and tells it to remind her later.

The door to the inner office opens. Five people emerge, Organisation executives and a few EAs, with briefcases and laptops. As a group, they head straight past the assistant’s desk and Quinn toward the lifts. Their security escort, a featureless man who has been waiting silently in the far corner of the reception area since before Quinn arrived, detaches from the wall and accompanies them.

Quinn recognises only one of the faces – Reinhardt, director of the Organisation in Germany. The Organisation hierarchy is an international sprawl, occluded and continually shifting, but she is a peer of Mahlo’s. Quinn doesn’t know the others. In any case, none of them glance in her direction.

And five more excruciating minutes pass.

‘No,’ Quinn mutters under her breath. ‘Sit still.’ The assistant doesn’t notice this.

Finally, Mahlo’s door opens again. A different man pokes his head around the door. He’s twenty-something, improbably youthful, like a teenager stuffed into one of his dad’s business shirts. His haircut is barely regulation. In one hand he holds a tablet computer showing his boss’s day planner. It’s packed. The man evidently does not sleep.

‘Marie? We’re ready for you now.’ ■

The office door closes behind them with a heavy mechanical clunk, as if the thing is part of a machine built into the office walls. While Quinn takes the indicated chair, the young man turns and does some confusing additional things to the door, causing it to make several further strange noises. Mahlo and the rest of his tier have non-trivial privacy and security requirements.

The office is spacious, but contrives to be dark despite two big corners of window and broad daylight outside. The walls are all bookshelves and dark wood panelling; perfectly stylish, but a style from the nineties, a little worn, and not yet old enough to have become fashionable again.

As for the fellow behind the desk: Mahlo is a relatively small, unassuming, sullen-faced man whose age is curiously difficult to place. Depending on how the light in the room catches his face, he looks twenty-nine or fifty-eight, and when he moves, reaching for a glass of water or a pen, he does so with the fragile care of a centenarian. The stripe on his pass is black.

Quinn forces herself to set her bag beside her chair, not clutch it defensively in her lap. She takes a deep breath. ‘So. What’s our topic? All I got was the meeting invitation, no agenda or subject. I mean, the UKI director says “jump,” you jump, but –’

Looking to her right, she notices that the young man, without saying anything or making any undue sound, has set his tablet down on a table, produced a gun, and aimed it at her head. Quinn stops talking. She sits still in her chair for a little while, absorbing the change of pace. Her heart rate rises to a hummingbird’s.

‘Okay?’ she hazards. She licks her lips and grips the armrests, otherwise staying perfectly still, waiting for another prompt. The young man’s face is totally neutral now, like this is just how meetings go.

Mahlo asks her, ‘Who do you work for?’

Quinn blinks. ‘What? Oh, God.’

He checks his notes. He speaks with a slow, almost soporific rhythm. ‘Marie Quinn, forty-nine. Married, no children. Avid hiker, adept climber, enjoys knitting and birdwatching. Sound education, airtight financials, a perfectly consistent background as far back as we can examine. And you’ve got full Organisation credentials that we’ve never issued, including access to a list of installations and rooms that . . . Well. Some of these locations don’t exist, or were torn down decades ago. At least one hasn’t been built yet, yet you’ve got the front door key to it. That’s before

we get to your level of access to the Unknowns themselves, which I can only term as “egregious.”

‘So you’re a spy, and your objectives are misaligned with ours, and young Mr Levene’s recommendation was to transfer you to Processing and let them unwind you, but I was able to bring him around. I talked him into a face-to-face. I thought there was a slim chance that if we locked you in a shielded room and asked politely, you’d have the good sense to spare yourself the rest.’

Quinn takes a shallow breath. She glances sideways at the gun. Levene hasn’t moved. ‘Mr Mahlo, you know me. We’ve met several times. I’m your chief of Antimemetics.’

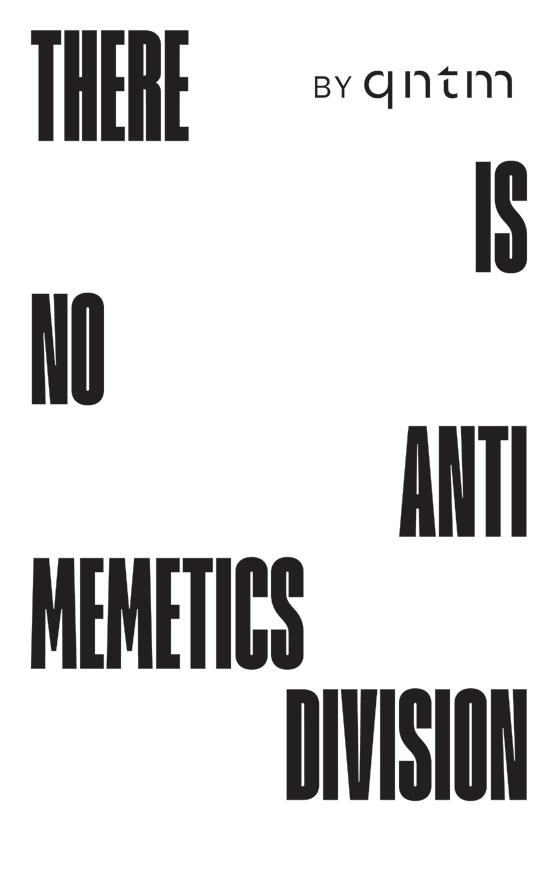

‘We don’t have an Antimemetics Division,’ Levene says.

‘. . . Mr Levene is mistaken,’ Quinn says, to Mahlo. ‘The Organisation has a research division for every class of Unknown and more. Telepathics, Inanimates, Cryptozoology. My division doesn’t always show up in the listing. It’s not something we can help. It’s the nature of the work we do.’

She hesitates. Silence from the other two. But she hasn’t been told to stop. Another glance at the gun.

She needs a raise.

‘There’s the easy stuff,’ she says. ‘There are Unknowns that are basic monsters. There are impossible books and haunted Siberian research labs and psychic teenagers and mythological swords that make you crazy. After that, things start to become interesting. There are Unknowns with dangerous memetic properties. There are contagious ideas, which require containment just like any physical threat. Viral concepts. They get inside your head, and ride your mind to reach other minds. And so, we have a Memetics Division. Right?’

‘Right,’ Mahlo says. He could name a score of Unknowns fitting this description without thinking.

‘There are Unknowns with antimemetic properties,’ Quinn goes on. ‘There are ideas that cannot be spread. There are entities and phenomena that harvest and consume information, particularly information about themselves. You take a Polaroid photo of one, it’ll never develop. You write a description down with a pen on paper and hand it to someone, but what you’ve written turns out to be hieroglyphs, and nobody can understand them, not even you. You can look directly at one and it won’t even be invisible, but you’ll still perceive nothing there. Dreams you can’t hold on to and secrets you can never share, and lies, and living conspiracies. It’s a conceptual ecosystem, of ideas consuming other ideas and . . . sometimes . . . segments of reality. Sometimes, people.

‘Which makes them a threat. That’s all there is to it. Antimemetic entities are dangerous and they are beyond our understanding; therefore, they fall within the Organisation’s remit. Hence, my division. This is our specialty. We can do the sideways thinking that’s necessary to combat something that can literally eat your combat training.

‘Mr Mahlo: You already know all of this. Dig deep.’

‘This is a cover story,’ Levene says to Mahlo, not taking his eyes off Quinn. ‘It’s a good one, but she’s had it worked out in advance.’

‘Levene, put it away,’ Mahlo says. Grudgingly, Levene does so. He backs up and leans against a bookcase, unconvinced.

Quinn breathes out.

‘Name one,’ Mahlo says. ‘Name an antimemetic Unknown.’

‘U-0055,’ Quinn says.

‘There is no U-0055,’ Levene snaps.

Quinn winces. ‘There is. Check the database.’

‘The reference numbers are assigned randomly,’ Levene says. Quinn opens her mouth to offer a small correction, but Levene doesn’t notice, and presses on. ‘There are gaps. That number hasn’t been assigned. It’s not superstition, we have enough to be concerned about without arbitrary numerological mysticism. We have U-0666 and U-0013. But there’s no U-0001. And there’s no U-0055.’

‘Levene,’ Mahlo says, ‘you should look at this.’ He turns his monitor so Levene can see the file he’s just retrieved. Levene circles around to behind Mahlo’s desk, and takes a look. He reads the file, from top to bottom. Stunned, he scrolls back and reads it all a second time.

‘You’ve seen this before?’ he asks Mahlo.

‘Never,’ Mahlo admits. He leans back in his chair, clasping his hands together. ‘As far as I can remember, anyway. If the content is accurate, we’ve both seen it dozens of times.’

Levene says, ‘It’s a con.’

‘Original file creation date is July 2005,’ Mahlo says. ‘It’s got all the right cryptographic signatures. Including mine. It’s real.’

‘Then she put it there! We don’t know how long she’s been spying here. Hidden until she needed it, right now.’

‘Let’s say it’s real,’ Mahlo says.

‘It isn’t possible.’

Quinn has to stifle a snort of laughter. ‘For Christ’s sake, Levene. Are you new?’

Levene glares at her. He circles the desk again, and advances on her.

‘Not yet,’ Mahlo says.

Levene slows. Still eyeing Quinn with suspicion, he takes up his station with his back to the bookcase again.

‘Let’s say it’s real,’ Mahlo repeats. ‘If it’s real, then who wrote the file? And how, for that matter, do you, Ms Quinn, retain knowledge of any of this?’

‘The file was written by Dr Edward Hix,’ Quinn says. ‘He used to work in my division. He’s dead.’

‘What happened to him?’

‘You don’t want to know what happened to him.’

There is a very long pause while both Mahlo and Levene react to this. In fact, they pass through a long sequence of discrete reactions. Indignation at the seeming rudeness; confusion at Quinn’s incaution in front of sinister superiors; surprise at the magnitude of the claim; pure disbelief; comprehension; and finally, horror.

‘What . . .’ Mahlo asks carefully, ‘would happen if we did know what happened to him?’

‘It would happen to you as well,’ Quinn says, levelly. ‘The circumstances of Dr Hix’s death are contagious, and the investigation is closed . . . As for your other question: we manage that pharmaceutically. I don’t need to lecture you about the challenges of secrecy in this line of work. You know that for as long as the Organisation has existed we have routinely used amnestic medications to suppress, alter, or erase problematic memories. Well, in the Antimemetics Division, we have the opposite problem. When we need to retain things that would otherwise be impossible to retain, we use mnestic medications. That’s “mnestic” with a silent M. Same Greek root as the word “mnemonic.” There are four families of the drug. W, X, Y and Z. Ah . . .’

In her bag, her phone has chimed again.

Slowly, with a nod of approval from Mahlo, Quinn reaches into her bag and turns her phone off, acknowledging the prompt this time instead of postponing it. She pulls a blister pack from the pocket beside it, and pops a pill out. It’s hexagonal, pale green. She holds it up, between a thumb and forefinger, and is relieved to see a flicker of recognition on Mahlo’s face. He is beginning to put it back together.

Quinn says, ‘These are Class W mnestics. The weakest, suitable for continual use. You take one every twelve hours, the more consistent the timing the better. You can order them through the Pharm. The pharmacist will claim they don’t stock any such thing. They’re misremembering, tell them to double-check.’

She swallows it, dry.

Mahlo grunts. ‘And now, I think, I see. I see why we’re having this conversation at all.’

‘You missed a dose,’ Quinn says. ‘You’re supposed to be on these, the same as me and everybody on my staff. It’s the only way we can work. You forgot to take a pill, and then you forgot all the information that the pills were helping you to retain. Why you were taking them, who gave them to you, where to get more. You forgot about me, and my entire division. And now I have to bring you up to speed.’

She offers the blister pack to Mahlo.

Levene steps forward, agitated. ‘Mr Mahlo.’

Mahlo takes the pack, pops a second pill out and studies it. ‘And if I take this,’ he says, ‘I’ll retain this whole conversation and we won’t have to have it again?’

‘I hope not,’ Quinn says, meaning it.

Mahlo swallows the pill, with a gulp of water from a glass.

Levene says, ‘Sir – !’

Mahlo silences him with a gesture.

Quinn’s and Levene’s eyes meet for a dangerous second.

‘. . . So what is U-0055?’ Mahlo asks. ‘Really?’

‘. . . U-0055 is nothing to worry about,’ Quinn says. ‘It’ll come back to you as the pill takes effect. As described in the file, it is an elementary information autosuppressor. A relatively weak one. We know it’s weak, because it’s the only antimemetic Unknown whose database entry is visible to the uninitiated. Excuse me, partially visible.’

‘Partially?’ Mahlo takes a second look at the file. He scrolls a little farther down.

There is more. He tilts his head thoughtfully, reading.

Levene pats the side of his chest with one hand. A look of puzzlement crosses his face. He frowns at Quinn, but she has looked away, momentarily, checking something on her phone.

‘Then how many other antimemetic Unknowns are there?’ Mahlo asks. He closes the file. ‘This one is weak. How much stronger do they get?’

‘Of two thousand, six hundred Unknowns and counting, exactly fifty-eight are currently known to be antimemetic in nature and are the responsibility of my division,’ Quinn says. ‘It’s statistically probable that at least ten more Unknowns have antimemetic nature of which the Organisation is unaware or only intermittently aware. Obviously those figures can’t include UUs. Most of the Unknowns I’ve mentioned are safely contained, but some aren’t. There are at least two of them in the room with us right now. Don’t look. I said, don’t look! It’s pointless.’

Mahlo raises an eyebrow, but doesn’t look. He keeps his attention focused on Quinn. Levene sweeps the whole room, even behind his back.

‘There is an invisible monster that follows me around and likes to eat my memories,’ Quinn explains, patiently. ‘U-4987. You’re about to say that there’s no U-4987, but there is. It’s something I’ve had to learn to live with. Call it an exotic pet. I produce tasty memories on purpose so it doesn’t eat something important, like my passwords or how to make coffee.’

‘And?’ Levene asks. ‘What’s the other one?’

With another nod from Mahlo, Quinn goes to her bag again. This time she pulls out a gun and shoots Levene twice in the heart.

More aghast than in pain, Levene collapses against the bookcase behind him. Pulling his head around to face Quinn, he manages, ‘How did you – kn –’

Quinn stands over him, aims more carefully and shoots him a third time, this time in the head.

Mahlo, again, simply declines to react to the turn of events. ‘That’s Levene’s gun,’ he notes. ‘I didn’t see you touch him.’

‘It’s tricky to steal a firearm from someone without them noticing,’ Quinn explains, unloading it and carefully setting it down on Mahlo’s desk. ‘But stealing a firearm and then stealing all memory of the theft is a little easier. Like I said: a pet. Some pets are intelligent enough that they can be trained.’

‘Fascinating,’ Mahlo says. ‘Advantageous, on occasion, clearly. But may I ask why?’

‘Because you were supposed to be taking Class W mnestics,’ Quinn says. ‘You can’t forget a dose of Class W mnestic. It’s been tried. You can postpone a dose, but you can’t forget unless someone actively prevents you from taking it for a significant period of time. There’s only one person who could get close enough to you to do that, and that’s your assistant. And remember when I asked him if he was new?’

‘He didn’t answer,’ Mahlo says. ‘I thought you were being rhetorical.’

‘He doesn’t work here,’ Quinn says. ‘He’s an Unknown. A humanoid antimeme. I checked the org chart, Mr Mahlo. You don’t have an assistant. You have a receptionist, her name is Rowland, and she’s outside. She’s the one who screens your calls and schedules your meetings. Levene doesn’t fit. He isn’t wearing the pass you and Rowland and I are all wearing. Look at this room. Where does he even sit? There’s no spare desk, in here or outside.’

Mahlo considers her points. He looks a shade unnerved.

Quinn goes on, ‘Don’t blame yourself. You’re human, and these things are redaction incarnate. You need to think like a space alien to get around them.’

‘It feels like I – we have a vulnerability here.’

‘No,’ Quinn reassures him. ‘We have a team.’

Mahlo rises up from his chair a little, taking a better look at what is left of Levene. He asks a question that, in any other workplace, would be absurd. ‘Is he dead?’

‘Maybe. I’ll put the corpse in our research queue and we’ll see what we can see when we open him up. But there’s a duality here. These are supposed to be distinct universes. It’s conceptual versus concrete, figurative versus physical. It’s very unusual for things to cross over. I don’t know what Levene was, but he had a human body, which immediately makes him weird, even by our standards. As ever, the search for balance continues. I will let you know if we get any closer.’

‘Any side effects of these pills?’ Mahlo asks.

‘Nausea, and dramatically increased risk of pancreatic cancer,’ Quinn says. ‘And very bad dreams.’