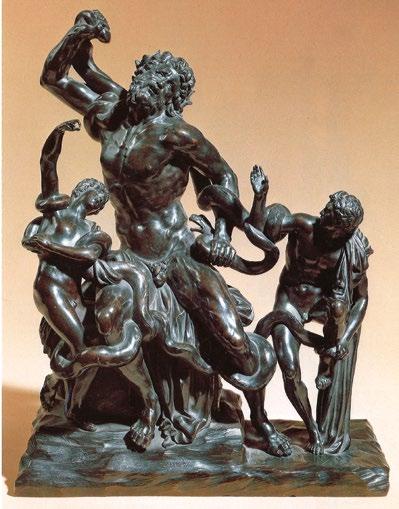

This publication discusses a bronze Laocoön (figs. 1, 17, 21, 22, 31, 35, 37; pls. II, IV, V b, VI a, VII, IX, XI, XII) recently sold at Bonham’s.1 Its new owners attributed it to Giuseppe Piamontini (1663–1744) ‘because of its manufacture and its extremely close proximity to the Doccia model’,2 the model employed for a porcelain Laocoön produced in the factory set up by Carlo Ginori (1702–57) in 1737 at Doccia near Florence.

Formerly in the collection of the British Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone (1809–98),3 this porcelain is preserved in the Museo Poldi Pezzoli (fig. 3; pls. I b, III b, V d, VI c, VIII b, X a).4 Its terminus ante quem is established thanks to a letter written on 27 October 1749 by Don Antonio, 2nd Duke Ruffo and 1st Prince of Floresta maritali nomine (1706–53), to Ginori and containing an order for porcelain sculptures that included a ‘Laoconte con suoi figli divorati dalli serpi’.5 This porcelain is based on a lost model Ginori bought in 1748, but – as we shall see – it is not this model’s exact replica and stands on a base of an unrelated model.

It will become clear below that the lost model acquired by Ginori in 1748 was a replica after the equally lost model for our bronze. Instead, the Museo Ginori preserves a later plaster (fig. 2; pls. Ia, III a, V c, VI b, VIII a, X b), first recorded at Doccia in a late 19th-century inventory.6 The lost model for the porcelain was sold to Ginori by Vincenzo Foggini (1692–1755).7 He was the eldest son of Giovan Battista (1652–1725) and heir to his father’s workshop where he would work until his death. Located in the Borgo Pinti, this workshop had been the seat of every sculptor to the Grand Duke of Tuscany from Giambologna onwards. From an invoice Vincenzo issued to Ginori on 8 June 1748, we learn that he charged ‘per gettare un gruppo grande di Laocoonte, un

vaso, e due bassirilievi antichi che sono alla base dell’Idolo di Galleria, e due altri bassirilievi’. 8 The invoice specifies that the sculptor had to retrieve the moulds necessary to cast these sculptures – a proof that they already existed and did not have to be specially made.9 Vincenzo’s invoice does not mention the material he cast (‘gettare’) into these moulds but only details ‘libbre 10 di pece greca’, ‘terra rossa, olio, e carbone’.10 These are the same ingredients he charged Ginori on the previous 8 March for ‘un Gruppo d’Apollo di cera’.11 The Laocoön Vincenzo sold to Ginori must therefore have also been made of wax. Indeed, a wax Laocoön is included in a post 1778–ante 1791 Doccia inventory of sculptural models for porcelain where it is described as ‘Gruppo di Laoconte. Del Foggini in cera con forma’.12 The ‘forma’, or mould, to which this inventory refers to, was a madre forma, or mother mould, composed of 24 piece-moulds. This is testified to by the contemporary and complementary – yet unpublished – inventory of the moulds that correspond to each model, which was drafted on the same occasion:13 ‘Gruppo del’Aoconte. Del Foggini con forme pezzi 24’.14 It was these piece moulds – taken from the wax in the factory – that served for making the Poldi Pezzoli porcelain (fig. 3). Their elevated number was necessary because of the models’ many undercuts. These were the same moulds that later served to cast the plaster in the Museo Ginori.15 This is confirmed by the fact that internal dimensions I took at the plaster are smaller than their equivalents in the bronze. There can therefore be no doubt that the plaster was made employing the moulds taken in the factory from the wax, which in turn had been made from the moulds taken from the model for the bronze.

Owing to the models’ and moulds’ inventories attribution of the lost Laocoön wax to ‘Foggini’ also the bronze has been attributed to Giovan Battista after its recent appearance in London.16 However, neither he nor Vincenzo invented its model. Nor can it have been created by Piamontini – the attribution endorsed by the Galerie Kugel which sold the bronze at the 2019 TEFAF in Maastricht to its present owner. In a paper held at the invitation of the Fondazione Museo Archivio Richard-Ginori della Manifattura di Doccia on 23 November 2022 in the Auditorium di Sant’Apollonia, Florence, during the conference La Manifattura Ginori e la circolazione dei modelli scultorei in Europa, I was able to prove that the author of the model was the young Filippo Della Valle (1698–1768),17 Foggini’s nephew. The present text is an enlarged version of my conference paper.

Laocoön by Filippo Della Valle

At the 2018 auction at Bonham’s the bronze was presented without reference to Doccia as ‘late 17th/early 18th century’ and ‘probably French’.18 It is first recorded with absolute certainty in the catalogue of the 1919 posthumous sale of the collection of Alfred-Louis Lebeuf de Montgermont (1841–1918)19 where it is described as ‘Important groupe en bronze patiné et doré, présentant le Laocoon, d’après l’antique du musée du Vatican, à Rome’ and catalogued as ‘Italie. Fin du XVIe siècle’.20 Bases similar to that on which it is shown in the catalogue (‘un socle en bois noir orné de bronze doré’) and which it still bears appear to have been devised especially for this collector as they were used for many of his bronzes. It is noteworthy that by 1783 a certain ‘M. Leboeuf’ owned a 24 pouces (64.8 cm) high bronze Laocoön by ‘Le Pautre’.21 If the indicated height includes the base, then it is possible that this Laocoön is our bronze, but to ascertain this it would be necessary to prove that Alfred-Louis Lebeuf de Montgermont descended from ‘M. Leboeuf’. Alfred-Louis also owned a pair of Piamontini bronzes, Bacchus and Ariadne and Venus and Cupid, 22 described in the 1919 auction catalogue as 17th century French.23 Perhaps this was a reason why the Laocoön’s new owners ascribed it to this sculptor in 2019. Already the porcelain Laocoön had been – wrongly – related to Piamontini by Alessandra Mottola Molfino. In 1976 she claimed that ‘si riferisce più direttamente’ to a 1716 ‘bronzetto del Piamontini’.24 No such bronzetto exists, but perhaps she meant Piamontini’s 1722 Sacrifice of Isaac (fig. 4) for Anna Maria Luisa de’ Medici, the Electress Palatine (1667–1743).25 Indeed, the model for the base of this bronze made of gilt bronze and lapis lazuli is the same – but for the cartouche and the uprights – as that of the Poldi Pezzoli porcelain.26 Mottola Molfino’s association of the model with Piamontini was taken up in the 2002 Catalogue of the Italian and Spanish Sculpture at the J. Paul Getty Museum, in an entry on a bronze Laocoön which had been considered French before being transformed into a work by Giovan Battista Foggini when the Getty bought it in 1985 (fig. 7).27 Thus a baseless attribution received credit that might have added to its 2019 endorsement by the bronze’s new owners.

Ginori destined the wax Laocoön to a most extraordinary assembly of sculptural prototypes for porcelain, described fifty-five years after this model’s acquisition as ‘il decoro della nostra Italia in ragione di scultura’.28 Located at the Doccia factory, it consisted of mostly wax and plaster statues, groups, and reliefs in various sizes and the corresponding moulds necessary for making the

dimitrios zikos

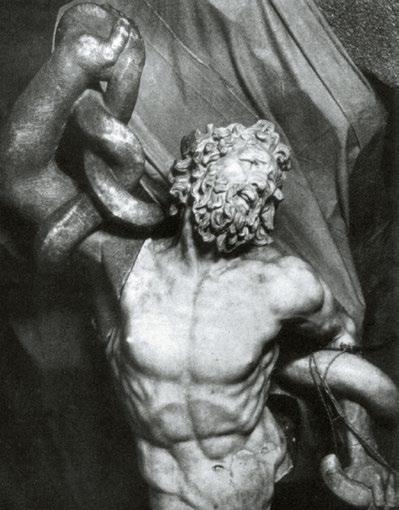

to have them cast in bronze.40 Antonio does not seem to have copied the Laocoön, but there is a splendid bronze reduction of the Vatican marble in the state of its 1530s restoration by Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli (1507–63; fig. 5), which bears all the marks of a Florentine mid 17th-century bronze. A unique cast (fig. 6), it was acquired by Prince Karl Eusebius of Liechtenstein (1611–84) probably during a tour of Italy in the 1630s and is first recorded in a 1658 inventory.41 It is commonly attributed to Antonio’s nephew Giovan Francesco Susini (1585–1653) who supplied other bronzes to the prince and could of course also have been produced by Giovan Francesco who we know spend some time in Rome copying antiques of which he produced splendid bronze reductions. If a replica ever ended up in Soldani’s workshop together with other Susini models,42 it did not enter Doccia since this Laocoön model is not present in the Doccia models’ collection. This applies also to the lost model after Baccio Bandinelli’s (1493–1560) Laocoön (fig. 8, pl. V a) Pietro Tacca (1577–1640) is known to have made.43 No contemporary source affords, moreover, the proof that Foggini and Piamontini ever attempted to model copies of the Laocoön.

Only Soldani turned to the subject. As a young man he made a bronze relief (fig. 9) for Johann Wilhelm, the Elector Palatine (1658–1716); as an eighty-year-old he proposed, on 18 May 1736, to send to London to Giovan Giacomo Zamboni ‘La statua del Laoconte in piccolo’,44 valued twenty doppie, but we don’t know whether such a bronze was ever made. There is a great likelihood that this ‘Laoconte in piccolo’ had already been offered to Zamboni and was of a model created by Soldani’s only peer absent from Doccia, Giovacchino Fortini (1670–1736), who died that same year, on 12 December. On 1 February 1720, Filippo Martelli had bought from Fortini a bronze Laocoön (figs. 10–11) for the price of fifty scudi, 45 still in the Casa Martelli, a rare case of a Florentine bronze having preserved its original varnish intact. Its chasing is the epitome of the finest Florentine Late Baroque coldwork. Four years later Fortini had made another Laocoön as we learn from a letter of 9 February 1725, written by his friend, the famous castrato Gaetano Berenstadt (1687–1734), to Zamboni. It was ‘fatto sul modellato di terracotta di Michelangelo ch’è divino, e rinettato in bronzo dal suo zio – Andrea Fortini – ch’à rinettato tutti i vostri gruppi allora quando stava col Soldani’.46

This must have been the ‘Gruppo di bronzo, che rappresenta del Laconte del signor Giovacchino Fortini’ displayed in the midst of paintings by Baldassarre Franceschini, called Il Volterrano, Cesare

around Laocoön’s right raised but bent arm the so-called ‘braccio di Michelangelo’, first recorded in 1720 (fig. 13).50 This is confirmed by a 1746 description – addressed by Lorenzo Maria Weber to Anton Francesco Gori (1691–1757) – of what must have been the Michelangelo terracotta model Berendstadt claimed had served Fortini as a model for his signed bronze version: ‘Un Laocoonte copiato dal Buonarroti da quello di Roma, da noi formato con gran suppliche, il quale lo possedeva il signore Giovacchino Fortini, questo è un Gruppo mirabile, e l’intrecciatura delle serpi variate, e più bizzarre.’51 It was two thirds of a braccio high and thus of approximately the same size as both Fortini Laocoontes. Lorenzo Maria Weber and his brother Anton Filippo Maria had worked with Soldani.52 And so had, as we have seen, Fortini’s uncle Andrea. Moreover, there is no huge price difference between the fifty scudi the Martelli cast had cost in 1720 and the 1736 asking price of twenty doppie (= 40 scudi), and so the ‘Laoconte in piccolo’ Soldani offered to Zamboni that year