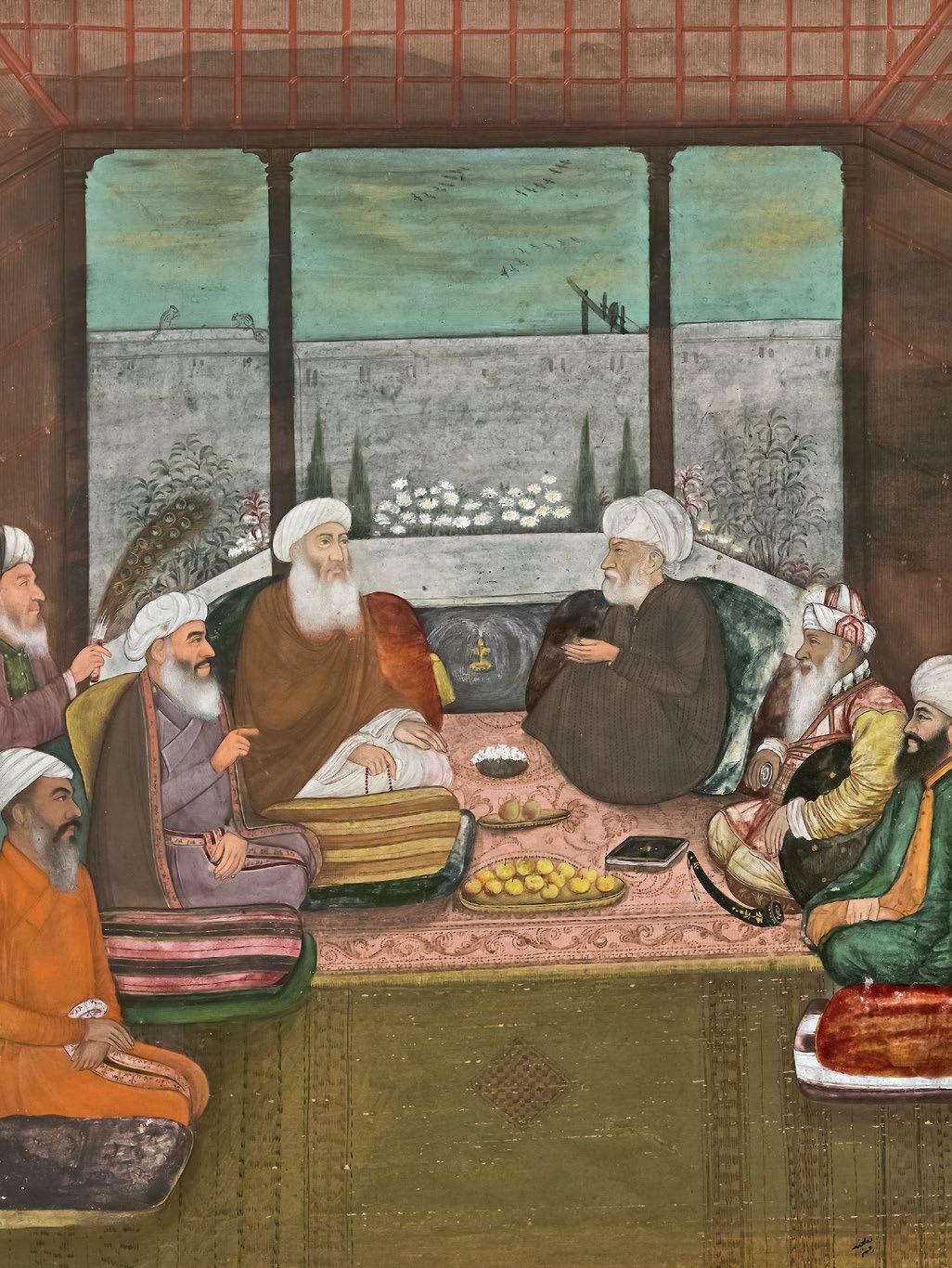

Six Wise Men Including Mian Mir and Mullah Shah in Discussion (detail), folio from the Ardeshir album, attributed to La’lchand India, Mughal period, 11th century AH/ mid-17th century CE, opaque watercolour, ink and gold on paper, 55.9 × 35 cm. Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, MS.826.2012

Foreword

Her Excellency Sheikha Al Mayassa bint Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani

Director’s Foreword

Shaika Nasser Al Nassr

Introduction

Tara Desjardins

Knead, Heat, Repeat: The Dough of Life

Nicoletta Fazio

Paradise’s Menu: Understanding the Food and Drinks of Jannah

Teslim Sanni

Cooking Across Empires: The Culinary Traditions of Medieval Islam

Daniel Newman

Setting the Table: Deluxe Glazed Ceramics and the Art of Fine Dining

Linda Komaroff

Itinerant Ingredients: The Global Trade in Foodstuffs

Tara Desjardins

Maryam Mohammed Abdulla: Crafting a Culinary Legacy in Qatar

Reem Aboughazala

Cultivating Resilience: Qatar’s Agricultural Innovations and the Future of Food Security

Teslim Sanni

Knead, Heat, Repeat: The Dough of Life

Nicoletta Fazio

Folio 76v (detail), Tacuinum Sanitatis (‘Almanac of Health’) , Italy, Sicily, c.1475 CE, ink and opaque watercolour on paper, 39.3 × 28.1 cm (closed). Museum of Islamic Art Library, Doha, RS79.L64.14[75]

[...] In my Divan I shall praise the cooked stuff; [...] Be it Rustam, or Bizhan, be it this or that, they all are running about and roaming in search of bread…

Boshaq At‘emeh Shirazi, Dastan-e Moza‘far u Boghra1

On certain days, if you walk out of the Museum of Islamic Art at the right time, together with sand and salt, the wind carries the smell of freshly baked bread. Under the jaguar sun, this hearty smell never fails to bring me back to my hometown in Italy, to a time when I was trotting my way to school and waves of warm aromas would hit me as bakeries opened their doors. Dreams of soft bread and crispy focaccia—there are certainly worse ways to start a day, or to end one. There seems to be something primal in such a feeling, something ancestral that speaks of life and the heart of people.

The bread fragrance filling the air of Doha’s Corniche comes from the imposing structures of Qatar’s Flour Mills, a presence as much solid as they are alive and in motion, with parts of the buildings destined to become the creative grist for art and culture.2 Standing as visual reminders of the transformation of a private activity into a fully industrialised process, the Flour Mills’ silos embody the everchanging face of a nation firmly rooted in tradition while jumping into a wild future.3 Bread indeed has this power. It elicits personal memories, as captured in the video installation A Thread of Light Between My Mother’s Fingers and

Daniel Newman

Cooking Across Empires: The Culinary Traditions of Medieval Islam

Sources for the culinary history in the Arabian Peninsula and the areas to the north—corresponding to what is today referred to as the Middle East—prior to the advent of Islam in the 1st century AH/ first quarter of the 7th century CE are few and far between. In the absence of cookbooks, our knowledge is limited to secondary sources, such as pre-Islamic poetry and early lexicography. The Peninsula was inhabited mostly by Bedouins, who were pastoral nomads, alongside sedentary populations in oases and towns, such as Makkah and Jeddah (known as Judda—meaning ‘road’— to medieval Arabic geographers). The desert dwellers frequently faced scarcity of food, and except for areas along the coast, where fish was a staple, most of the region’s inhabitants relied on what little their inhospitable environment provided: bread (usually made from millet), dates and milk, occasionally supplemented with the meat of the camel, sheep and desert animals. Other items, such as onions, garlic, grapes, figs, olives and gourds are mentioned in the Qur’an, alongside the more exotic pomegranate, ginger, mustard and basil, which came from outside the Peninsula and bear evidence to its role as an international trading hub. Hadiths, the sayings of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), make up another fertile source since they contain a number of references to food and dishes, as well as dietetic recommendations. For instance, the Prophet is reported to have warned against excess eating by pointing out that one-third of the stomach is for food, one-third for drink, and one-third for breath.

The diet was very simple and highly sustainable, with nothing going to waste. It mainly comprised gruels and porridges such

Linda Komaroff

Itinerant Ingredients: The Global Trade in Foodstuffs

Tara Desjardins

Folio 62v (detail), Tacuinum Sanitatis (‘Almanac of Health’) Italy, Sicily, c. 1475 CE, ink and opaque watercolour on paper, 39.3 × 28.1 cm (closed). Museum of Islamic Art Library, Doha, RS79.L64.14[75]

Throughout history, cuisines have evolved with the arrival of new ingredients, some introduced through trade and others through encounters between cultures and communities. Some of these ingredients took time to be integrated into popular dishes, while others were adopted immediately. Today, the origin of many ingredients commonly found in dishes widely considered to be national favourites are long forgotten, their journeys across time and place absorbed into the many dishes they flavour. However, it is through trade, especially in the Abbasid period in the 2nd century AH/8th century CE, and later with the European ‘discovery’ of maritime trade routes in the late 9th century AH/15th century CE, that many ingredients were introduced into Eastern cuisines. This essay explores this phenomenon through the examples of wheat, aubergine, chilli peppers, and the potato, documenting each one’s culinary journey from Asia and the Americas to Europe and the Middle East.

It was not until the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate (132–656 AH/ 750–1258 CE) moved from Damascus to the newly built city of Baghdad in 144 AH/762 CE that a rich culinary culture began to emerge at the Abbasid court. This phenomenon was largely fuelled by innovations in irrigation, navigation and transport, which spurred a revolution in both agriculture and gastronomy. The agricultural revolution was, at first, a result of Baghdad’s strategic location, nestled in the fertile lands of the Jazira between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, an area naturally suited to the cultivation of crops. The early Abbasids exploited this by building a complex system of canals and waterways that could

Teslim Sanni

Cultivating Resilience: Qatar’s Agricultural Innovations and the Future of Food Security

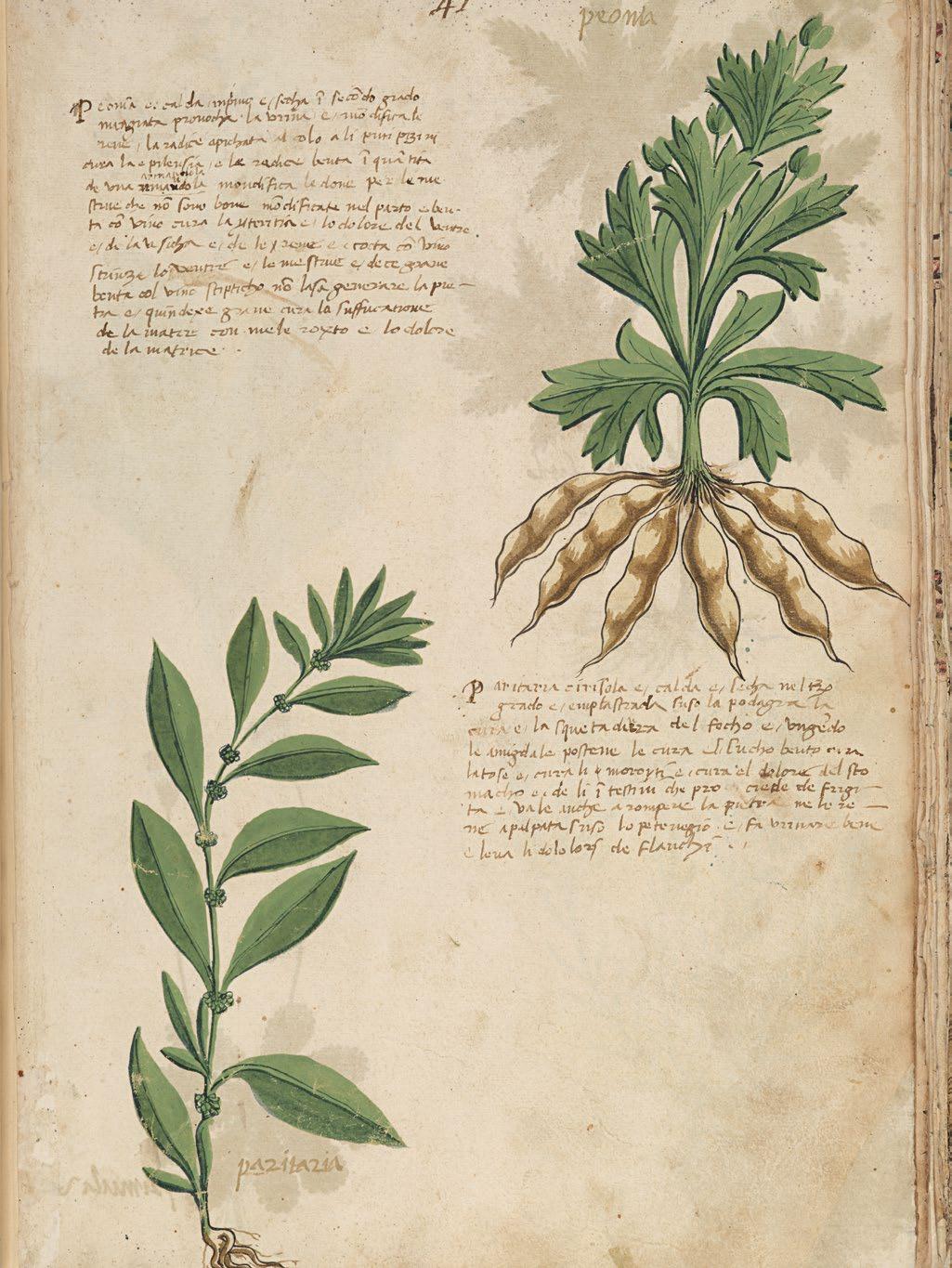

Folio 41r (detail), Tacuinum Sanitatis (‘Almanac of Health’) Italy, Sicily, c. 1475 CE, ink and opaque watercolour on paper, 39.3 × 28.1 cm (closed). Museum of Islamic Art Library, Doha, RS79.L64.14[75]

The agricultural sector across the Arab world has long grappled with significant challenges, including arid climates, water scarcity and the growing impacts of global warming. Qatar, a noteworthy example in this context, has taken proactive steps to address these issues by enacting sustainable agricultural practices. Before the sudden 2017–2021 blockade imposed by neighbouring Gulf countries Bahrain, the UAE and Saudi Arabia these nations provided over 80% of Qatar’s food imports.1 The blockade, which involved severing diplomatic ties, closing borders and restricting food exports to Qatar, intensified the nation’s focus on food security and self-sufficiency. It also accelerated Qatar’s commitment to sustainable agriculture, an effort that began nearly a decade earlier. By investing in modern farming technologies and adapting to both environmental and geopolitical challenges, Qatar has made substantial strides toward food self-sufficiency while reinforcing its resilience and resourcefulness.

One of the primary environmental issues facing Qatar— and the Arab world at large—is its desert climate and limited access to fresh water, making food production a significant challenge. Prior to 2008, Qatar relied on imports for over 90% of its food supply. However, in response to the 2008 global food crisis and concerns about potential future disruptions, the Qatari government launched its first Qatar National Food Security Programme (QNFSP), adopting advanced agricultural technologies in order to achieve national food security, which aligned with the Qatar National Vision 2030.2 This included the

6

Tray with ship (‘junk’)

India (Surat or Cambay), Mughal period, 10th–11th century AH/late 16th–early 17th century CE Lacquered and gilded turned wood ∅ 75 cm

Museum of Islamic Art, WW.110.2007

1 See, for example, a small box in the David Collection, Copenhagen (49/1998), as well as the article by Folsach, ‘A Number of Pigmented Wooden Objects’, particularly figs 22 and 23, pp. 88–89.

2 See Anjum, ‘Ship Construction in Mughal India’, p. 298.

3 See the painting currently in the Victoria & Albert Museum, London (IS.2:4-1896).

Lacquered wooden objects from the early medieval Islamic period are generally attributed to Iran or Afghanistan.1 This tray, however, finds closer parallels with 10th–11th century AH/16th–17th century CE lacquer and mother-of-pearl caskets, cabinets and dishes made in Gujarat a region on the western coast of India known for its fine woodworking. The Mughal emperor Akbar conquered Gujarat in 979 AH/1572 CE, gaining direct access to the Red Sea and the wealth of imports (and ingredients) arriving into the ports of Surat and Cambay in exchange for spices and silks. This impressively large, lacquered tray was once gilded, suggesting it was only used as a commemorative dish to serve or present items. It depicts a ship carrying one mainsail. Known in Mughal sources as a ‘junk’, these ships could swiftly harness the favourable monsoon winds needed to travel by sea. Emperor Akbar’s 10th century AH/16th century CE court history, the Akbarnama (Book of Akbar), mentions a ‘caravan of junk-voyagers’ (qafila-yi jank) when speaking of a group of family members voyaging from Gujarat to Mecca on hajj 2 In 983 AH/1576 CE, Akbar’s aunt, Gulbadan Begum, and other women of the imperial family made their first perilous pilgrimage to Mecca on a single-mast ship similar to the one illustrated on this tray. The two-tiered, domed structures seen on the tray represent curtained quarters where women would have been concealed, as seen in the late 16th century painting depicting a voyage from Delhi to Agra by river.3 On this tray, the orange panels hanging vertically on the front of the structure likely depict the type of velvet curtains seen in the painting. TD

19 Ewer Afghanistan (possibly Herat), Ilkhanid period, late 7th–early 8th century AH/late 13th–early 14th century CE

Hammered brass inlaid with silver, copper and black compound

39.9 × ∅ 22 cm

Museum of Islamic Art, MW.118.1999

This ewer (aftaba or abdasta) retains a powerful and luxurious presence despite having lost much of its original silver and copper inlaid decoration. It must have made quite an impression when handled during banquets in an affluent household. Based on an inscription applied to a similar ewer now at the British Museum (1848,0805.2), we know that this type of vessel was used to pour water for washing hands, an essential part of dining etiquette in cultures in which food is consumed from large communal plates. Traditionally, the right hand was used to pass dishes and to eat, a habit still practised in various regions of West and South Asia, and across Africa.1 In elite and wealthy households, ewers such as this were accompanied by an equally lavish tast, a basin used to collect the water, typically scented with rose extract, musk, frankincense, sandalwood or camphor, as it was poured over a guest’s hands.

This ewer belongs to a small group of similar vessels used for banquets. Its polylobed body showcases intertwined vegetal trellises alternating with a series of roundels with figural decoration, including enthroned male figures and mounted falconers and hunters accompanied by small quadrupeds. Royal figures and hunting scenes are among the most popular themes on metalwork produced for the elite in this period, motifs that have long been associated with the ideals of royalty and nobility across Eurasia. In addition to this impressive repertoire of motifs, the top part of the ewer presents a band of horsemen hunting small felines, perhaps cheetahs, which were often used as hunting auxiliaries during royal campaigns. The shoulder bears an inscription in a style regularly appearing in inlaid metalwork of the time: vertical letters terminating in small human heads, and the reserve space filled with small birds of prey. The tall slender neck shows a dense combination of diverse motifs including calligraphy, vegetal branches, bands of leaping and running animals, and hunters on horseback. A couple of seated tigers cast in relief, another recurrent feature of brass wares from this region and period, complete the rich overall decorative programme. NF

Inscription:

Health, safety, health and ease

(on the neck)

‘Glory, prosperity, longevity, happiness, (God’s) care, safety, ease and wellbeing (?)’ (on the shoulder)

1 In many cultures, historical as well as contemporary, the right hand is associated with cleanliness and proper manners. One Hadith reports that the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) indicates the right hand as the proper one to eat, see Hadith no 5265, Sahih Muslim, vol. 5, pp. 369–370.

PUBLISHING AND DISTRIBUTION

Qatar Museums

Doha, Qatar

www.qm.org.qa

Silvana Editoriale

Milan, Italy

www.silvaneditoriale.it

First published in 2025 by Silvana Editoriale in collaboration with Qatar Museums

© 2025 Qatar Museums

All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Printed and bound in Italy. First edition

ISBN: 9788836661107 (Silvana Editoriale)

ISBN: 9789927184024 (Qatar Museums)

Qatari Legal Deposit No: 549/2025