Another, very similarly painted rose, is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (p.51), and other versions also exist. The reference to the Irish poet and playwright Oscar Wilde (1854–1900) offers the viewer a raft of possible connections and meanings. The strokes of darker paint that outline the petals towards the lower half of the flower jostle together to suggest a skull-like grin. Two eyes appear to complement this visage within the blend of reds and yellows, while pinkyred buds bracket the main bloom. The anthropomorphic appearance is at once witty and sinister, perhaps conjuring up thoughts of the hidden face behind the eternal portrait of Dorian Gray.

Interestingly, Kiefer proffers a rose, and not a green carnation, as we might expect in connection to Wilde. On the opening night of his play, Lady Windermere’s Fan in 1892, Wilde, aware of the potential symbolism of flowers, asked some friends to wear green carnations on their lapels, turning this gesture into a secret code for homosexual recognition. In contrast to the carnation (and possibly less effete) the rose is unisex, democratic, and ubiquitous as a symbol of love, and when faded, dried, and desiccated it turns into a lovelorn and fragile memento mori.

In 1888, Wilde wrote The Nightingale and the Rose, a story that considers the rose in relation to human desire and fickleness.16 The tale is predicated on the necessity of finding a red rose for a student to give to the subject of his affections. A nightingale wants to help the besotted student in his seemingly hopeless quest for the symbolic red rose. Meanwhile, the rose trees chime with poetic descriptions but of ‘wrong-coloured’ roses: ‘My roses are white ... as white as the foam of the sea, and whiter than the snow upon the mountain.’ To create a red rose the nightingale is told she must ‘stain it with [her] own heart’s-blood’. The nightingale sings all night, her chest pressed up against

the thorn of the rose tree, and she dies giving the rose its red colour with her blood. When the morning comes, the student finds the red rose and presents it to the girl, but she rejects it, for it does not match her dress. In anger, he throws the rose away callously, concluding:

What a silly thing Love is ... It is not half as useful as Logic, for it does not prove anything, and it is always telling one of things that are not going to happen, and making one believe things that are not true.

Without the dedication, Kiefer’s flower painting could remain quirky and lightweight. It does not relate to the wider realm of traditional flower painting but, as is often the case, it is self-reflexive with other Kiefer strands. However, the Wilde reference adds gravitas, allowing the work to become a springboard for our imagination. We can explore his story and segue into others. These other stories deepen his repetitious rose pictures, broadening out his theme. Because the rose is so universal, it recurs as a motif in many kinds of literary references applied to all types of situations, not only that of love. It is therefore interesting to expand on the theme as it appears in text and appreciate how this simple flower is in fact a very loaded bloom. The rose can be read as a mantra in the same way that Kiefer produces his repetitive repertoire of symbolic icons, be they rose or Valkyrie.

William Shakespeare (1564–1616) immediately comes to mind, and a different (from Wilde’s) kind of tragedy with the star-crossed lovers in Romeo and Juliet (Act II, Scene II): ‘What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet; So Romeo would, were he not Romeo call’d.’

Gertrude Stein (1874–1946) wrote, ‘A Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose’ in her 1913 poem ‘Sacred Emily’.17 The first ‘Rose’ is the name of a person. The quotation became Stein’s most famous, introducing the concept

Anselm Kiefer

Von Oskar Wilde

(From Oscar Wilde), 1974

Watercolour and gouache on paper, 40 × 29.8 cm

of the philosophy of the law of identity, ‘things are what they are’, the sentence expresses the fact that simply using the name of a thing already invokes the imagery and emotions associated with it. Kiefer’s rose paintings are straightforward yet carefree depictions of the familiar form of that genus. It is his dedication that expands our thoughts and offers us further possibilities of interpretation.

Kiefer’s rose is a pretty vehicle for the mind to wander around. We recognise its shape and smell, the thorns, and pinnate leaf format. Katherine Mansfield (1888–1923) employs a celestial garden rose to open the scene of another type of veiled tragedy in her short story, The Garden Party (1922), written 34 years after Wilde’s Nightingale:

As for the roses, you could not help feeling they understood that roses are the only flowers that impress people at garden-parties; the only flowers that everybody is certain of knowing. Hundreds, yes, literally hundreds had come out in a single night; the green bushes bowed down as though they had been visited by archangels …18

Mansfield’s opening lines clarify the ubiquitous status of the rose, but her comment about ‘everybody’ is ambiguous as this tale is about class consciousness (among other things) and perhaps only alludes to those (like Oscar Wilde?) who attend garden parties.19

A poem by Fabian Peake (b.1942) treats us to yet another perspective on role reversal and this versatile flower. It was written in response to a gift from his wife, the sculptor Phyllida Barlow (1944–2023):

She brought me home a rose of welded metal, a slender stem with a head of tempered petals.

I found a cut glass vase, blew away the dust, immersed the rod in water and watched the flower rust.20

THE DREAM KING, 1974

With Anselm Kiefer’s proclivity for mythic characters, it is perhaps no surprise that he created portraits of Ludwig II von Bayern. This was a king known to favour extravagant artistic and architectural projects over the day-to-day business of state, and who commissioned Richard Wagner’s Ring Cycle, a series of epic musical dramas that Kiefer also examined through his work (pp.121–4, 165–8, and 178–81).

This bust-length portrait shows Ludwig II, in three-quarter profile, his head turned slightly to the left towards the viewer. That head sits on top of his stiff white collar like a precarious egg balancing on a cup. Kiefer’s ‘dream king’ suggests an insecure monarch whose military attire has never seen a battlefield. This is no Richard III (1452–1485). The inference here is that Ludwig’s outfit is all puff and coded dress, make believe and fake protection. The high collar is rigid, the material is heavy, the sash of honour decorative.

Yet, if we view him in the company of other uniformed soldiers, he fits the brief. His solitary head and shoulders resonate with the 1812–14 portrait by Francisco de Goya (1746–1828) of Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington (1769–1852), a work now in the collection of the National Gallery, London (p.54). The eyes in that portrait also evoke a curious expression, perhaps a haunted look. But unlike Ludwig II, Wellington experienced battle, and Goya’s

elementary particles.36

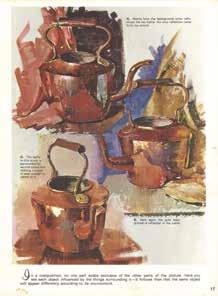

As Seiler’s interpretation of Kiefer’s unusual work suggests, a still life – regardless of the long art historical tradition of the genre and its popularity amongst amateur painters – can still move viewers today. A still life can, indeed, be exciting.

Lena Fritsch

DASDEUTSCHEVOLKSGESICHT.KOHLEFÜR

2000 JAHRE (THE FACE OF THE GERMAN PEOPLE. COAL FOR 2000 YEARS), 1974

In 1932, a year before the National Socialists seized power in Germany, a small Berlin publishing company, Kulturelle Verlagsgesellschaft, published an elaborately designed photobook by German photographer Erna LendvaiDircksen (1883–1962) titled Das deutsche Volksgesicht (The Face of the German People). It consisted of 140 highquality copper-plate prints in black and white, showing full-size portrait photographs. A folksy selection of short texts complements the images: citations, poetry lines, and comments by the artist herself. These portraits showed predominantly elderly residents of different rural regions of Germany, from North Frisia down to Upper Bavaria. The sitters remain anonymous; their attributes, costumes, and the titles assign them to certain regions and professions, such as ‘peasant from the Altland’ and ‘Frisian Fisherman from the Wursten Marsh’.37 Whereas the texts have been set in the old fashioned Fraktur – a font claimed to be typically German – the portrait photographs make use of a Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) modernist visual language, such as sharp black and white contrasts, clear

(left)

Cover of Still Life is Exciting magazine by Nan Greacan, c.1965 (right)

Still lifes of a copper kettle, feature in Still Life is Exciting magazine by Nan Greacan, c.1965

lines, and closely observed details. Indeed, this book belongs to a particular photographic genre, which had already become popular in the 1920s by Neue Sachlichkeit photographers like August Sander (1876–1964) with his 1929 photobook Antlitz der Zeit (Face of the Time), or with Helmar Lerski’s Köpfe des Alltags (Everyday Heads; 1931), and other ideologically quite unsuspicious photographers, without any racial or nationalist motifs. Nevertheless, the collective ‘Germanic’ approach to portrait photography, as performed by Erna Lendvai-Dircksen and other contemporaries, was set to please the Nazis, as it complied perfectly with their project to inventory the anthropological and physiognomic traits of ‘the German’, in distinction to people of foreign origin or ‘race’. After 1933, picture books like Das deutsche Frauenantlitz (The German Woman’s Countenance) or Das Gesicht des deutschen Arbeiters (The German Worker’s Face) spread rapidly. Their titles were kept in the singular in order to typify ‘the German nature’ and to suggest it as ethnically normative.

Lendvai-Dircksen often captured her ‘German faces’ close up. In their features, particularly in those marked by old age, the native landscape is almost metaphorically present: furrowed, gnarled, wrinkled, and creased. This is, above all, the result of a refined photographic staging that creates these effects. The face of the traditional rural population was, according to the photographer’s basic concept, shaped by nature itself. Thus, its perfect form could only be found in the countenances of elderly rural people. Their continued existence was at risk, allegedly due to racial degeneration, which is why Lendvai-Dircksen considered it her task to create a photographic record of the German native people; out of their totality she created a collective ‘face of the German race’. Her book, and even more so the subsequent volumes that she edited after 1935, confront the reader openly with their racist mindset. They fit seamlessly into the national socialists’ propaganda

machinery: ‘Erna Lendvai-Dircksen understands the face as a venue for ideological conflict.’38 In the context of his artistic research on National Socialist ideologies and aesthetics, as well as the precarious role of the artist, in 1974 Anselm Kiefer dealt with this photobook intensively in a process of re-enactment and imaginative continuation. Measuring 57 × 45 × 6 cm, Kiefer’s Volksgesicht is unwieldy and much larger than Lendvai-Dircksen’s 18 × 15 × 2 cm edition, and, with 182 pages, more voluminous than the original also. It is composed of two separate parts. First, Kiefer photocopied and enlarged a selection of Lendvai-Dircksen’s photographs, which he put in his own order. Then, he mounted this ‘photocopybook’ onto a larger book-like object, which protrudes over the side edges like a frame. Title and subtitle, written in Kiefer’s typical schoolchild handwriting, are permanently visible when turning the pages: ‘Das deutsche Volksgesicht. Kohle für 2000 Jahre’. The second part of the title, Kohle für 2000 Jahre (Coal for 2000 Years), reflects, ironically, the Nazi’s presumptuous idea of a ‘thousandyear-long Reich’, which fortunately, was to last for ‘only’ twelve years in the end. Anselm Kiefer has stated that:

The coal, coming into existence over the course of millions of years from the left over of plants, represents the geological time, which will outlive the thousandyear-long Reich that humans were striving for, exposing it as insignificant and megalomaniacal.39

The larger book-object, made by Kiefer himself, consists of 50 sheets of thick woodchip wallpaper. It also has two separate sections: the beginning shows large charcoal drawings that remind us of rough Expressionist woodcuts; they are inserted transversely to the photocopies of the smaller book, which means that the reader has to rotate the object in order to recognise individual faces from the latter (pp.128–9). They have been graphically transformed, coarsened, and distorted. Kiefer reworked the sheets

of Mankind), 1961.

using a frottage technique, so that the contours and features gradually merge with the contrasting structure of the wooden elements – as the curator Mark Rosenthal wrote: ‘Peasant’s faces emerge from the linear patterns of woodcuts with the effect that their features are thoroughly one with the land.’40 The second part of this wallpaper book shows a sequence of double pages, covered with undecipherable signs and geometrical patterns, which could be representing aerial views as well as pure painterly abstractions, in rhythmic alternation with double pages, deeply blackened with tar and emulsion paint that extinguish everything underneath.

Kiefer was to return to the idea of lining up portrait heads in an ‘ancestral gallery’ only a few years later in his great cycle on the theme of Hermannsschlacht. Here, however, the archetypal German is no longer embodied by the rustic type, rather low in spirit, but by ‘spiritual heroes’, who, during the nineteenth century, had prepared the ground for the Nazi’s racial thought-patterns. The praise of the rural life with its soil – the so called ‘Blut und Boden’ ideology – belonged, just like the worship of the spiritual leader – the cult of the Führer – to the great Nazi founding myths; their impact extended well into the 1950s and 1960s, as a glance at German school books from Kiefer’s schooldays proves.

In 1961 a new edition of Lendvai-Dircksen’s Das deutsche Volksgesicht was published, although under the softened title Ein deutsches Menschenbild (A German Image of Mankind; above). In 2003, it was once again reedited; this time a young girl’s face adorned the cover.

Time and again, Anselm Kiefer has carried out profound artistic research on the ideologically burdened ways of German thinking and creating; at an early stage, he already dared to track down and denounce their return –and to extinguish them.

Sabine Schütz

Watercolour, gouache and ballpoint pen on paper

20.5 × 28.5 cm

(PALETTE WITH WINGS), 1978

acrylic and shellac on burlap 116 × 145.6 cm

Watercolour on paper

49.5 cm × 64 cm Hall Collection