Humani nihil a me alienum puto Publius Terentius Afer, Heautontimorùmenos (165 BC), l. 77

The first time I had the privilege of admiring the Florentine Codex in person was thanks to Rafael Tovar y de Teresa during his first official visit to Florence, after he had been appointed Mexican Ambassador to Italy. Don Rafael’s excitement over seeing Brother Bernardino de Sahagún’s original manuscript pages in the small room where we were allowed to look at them in private was enormous. And for me, it was love at first sight. It was also the first time I had admired the interior of the marvellous Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, designed by the divine Michelangelo at the request of the Medici pope, Clement VII. In that moment I realised that the richest and most profound connection between Mexico and Italy is enshrined in this marvellous treasure chest of Renaissance architecture in Florence. The year was 2003.

Some time later, I attended the conference organised by the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana on the Historia general de las cosas de Nueva España – the occasion was the 2007 European Heritage Days. I was surprised by the questions from the audience at the end of the speeches, since among the various topics discussed – which ranged from human sacrifices and anthropophagy to the Aztec calendar and the pyramids – it was the subject of chocolate that caught the audience’s attention. In fact, the original recipe for chocolate is transcribed in the Florentine Codex, dated 1577, along with its many variations. This was the moment when the idea of ‘Entre dos Mundos’ came into being, a project that would research and explore how the Old and New Worlds influenced each other, leaving indelible traces in their history and culture. Todorov was right when he repeatedly affirmed that ‘The past is fruitful not when it serves to nourish resentment or triumphalism, but when its bitter taste compels us to transform ourselves’ (L’Homme dépaysé, Paris, 1996, p. 71).

‘Ayaucoçamalotl’ (rainbow). Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Mediceo Palatino 219, Mexico, 16th century (1577), fol. 238r, detail.

Sahagún’s books led me to other extraordinary texts, which were deeply inspiring for me. The first was Colors Between Two Worlds. The Florentine Codex of Bernardino de Sahagún, published by The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies. Its evocative title came from Diana Magaloni Kerpel, former director of the Museo Nacional de Antropología, and her intense description of the Florentine Codex: ‘The result, a truly unique masterpiece … is also a history of the conflict, negotiation and dialogue between two different worlds … it is a carefully and skilfully crafted work of art whose material qualities and historic context bear the indelible marks of an epic battle for survival’ (Ida Giovanna Rao, Diana Magaloni, Alessandra Pecci, Il mondo degli Aztechi nel Codice Fiorentino, Florence, 2007, pp. 12–13). The image Ayaucoçamalotl, from the Sahagún Codex, decorates the back cover of the volume. It is a colourful rainbow, which literally acts as a symbol uniting two opposites. A fascinating emblem for the uniting of antipodes. The ‘Entre dos Mundos’ cultural association project took its name and logo from Colors Between Two Worlds. The second book that inspired me was La conquête de l’Amérique. La question de l’autre, by Tzvetan Todorov – where ‘the Other’ is ‘the Different one’ –, a text that encourages us to reflect on the relationship between individuals belonging to different cultures and social groups starting with historical memory: ‘I am writing this book to prevent this story and a thousand others like it from being forgotten. I believe in the necessity of “seeking the truth” and in the obligation of making it known … My hope is … that we remember what can happen if we do not succeed in discovering the other’ (Paris 1982, Eng. trans. New York 1984, p. 247). Finally, the pivotal book, the primary source for the exhibition and educational project ‘Cacao Entre Dos Mundos’, I found during a wonderful visit to the Museo de Anthropologia in Mexico City: the Spanish edition of the most thorough publication on the history of chocolate, The True History of Chocolate by Sophie D. Coe and Michael D. Coe, anthropologists at Yale University, revised in Rome by Michael after the untimely death of his Sophie. The authors use the original sources on the history of cocoa because ‘much food writing about chocolate’s past falls into the category of Voltaire’s “accepted fiction”.’ (London 1996, p. 12).

The ‘Cacao Entre Dos Mundos’ project is being realised on the occasion of the 500th anniversary of the start of the Spiritual Conquest that took the friar Bernardino de Sahagún to Mexico. The first venue is the majestic Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana. Against the backdrop of the resplendent green of the quetzal, maps and archaeological, historical, artistic and artisan artefacts tell the story of chocolate, from the Mesoamerica of the Olmecs to the ‘bean to bar’ movement, a beacon of hope in respect to ‘the Other’. The narrative guide is provided by the twelve books

of the Historia general de las cosas de Nueva España by Sahagún, who, as Miguel León-Portilla reminds us, with ‘his humanism as a Renaissance Spaniard, he made the saying that no human reality can be foreign become true’ (El México Antiguo en la historia universal, Mexico, 2015, p. 77).

Ruby E. Villareal V. President of the ‘Entre dos Mundos’ cultural association

Acknowledgements

The collective creation common to the indigenous world and intrinsic in Sahagún’s work also applies to the exhibition ‘Cacao Entre Dos Mundos’, which is the result of a great deal of collective work: Antonio Aimi, Soraya Al azzam, Eugenia Antonucci, Francesca M. Anzelmo, Roberta Avena, Nicoletta Bardossi, Ilaria Bartocci, Giulia Basilissi, Diana Beltrán, Filippo Camerota, Roberto Caraceni, Azzurra Carmosino, Laura Carrillo, Stefano Casciu, Maurizio Catalano, Guido Catani, Rebeca Chavez, Claudio Chiarusi, Martin Christy, Mario Curia, Eduardo de la Cruz, Cosimo Di Nocera, Elisa Díaz, Davide Domenici, Lourdes Echavarria, Simone Falteri, Davide Ferrero, Cosimo Frezzolini, Elyn Fuentes, Francesca Gallori, Eugenio Giani, Marcela Gómez, Gabriele Gori, Carla Guarducci, Lorenzo Hofstetter, Mario Iozzo, Daniela Konyk, Elena Landini, Donatella Lippi, Roberto Maltagliati, Roberta Masini, Ottaviano de’ Medici, Ángel Méndez, Monica Meschini, Andrea Micozzi, Eduardo Matos Moctezuma, Massimo Montanari, Vincenzo Muscolo, José Antonio Nieves, Alejandra Ortiz, Cinzia Ortri, Maurizio Palatresi, Monica Patiño, Mauro Pellegrino, Claudio Pistocchi, Gabriela Ramirez, René Renteria, Kim Richter, Pierpaolo Ruta, Valentina Saetti, Maria Salemi, Marco Salucci, Enrico Sassonia, Silvia Scipioni, Martha Sepulveda, Paolo Staccoli, Antonietta Troiano, Paola Vannucchi, Nicolò Vellino, Danielo Vestri, Andrea Viliani, Elisa Villarreal, Juan Villoro, and Mario Wong.

Thank you for the invaluable support: Rogelio Hernández, Humberto Tijerina.

Thank you for the special emotional support: Babbo Alfonso, Jorge Guerra, Raquenel Hernández, Melisa Martínez, Lara Pasquarelli, Luca Pasquarelli, Mamma Ruby, Cynthia Salas, Jorge Tijerina, Lupita Tijerina, Elisa Villarreal.

Thank you for your immense heart: Antica Dolceria Bonajuto, Casa Nahuatl, La Cucaracha, Gelateria della Passera, Istituto Lorenzo de’ Medici, Nicolò Vellino, Staccoli, Vestri Cioccolato.

Thank you above and beyond for enriching the project before getting started: Raquenel Cázares, Edmundo Escamilla, Yuri de Gortari, Zoila Vargas.

Authors of the texts

[l.h.] Lorenzo Hofstetter [r.V.] Ruby E. Villarreal V.

On the occasion of their 500th anniversary, we recall two conceptually distant yet converging events: the start of Michelangelo Buonarroti’s commission from Pope Clement VII to design the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, and the beginning of the ‘Spiritual Conquest’ of the New World with the arrival of the first religious brothers of the mendicant orders in America in 1523. These events determined the genesis and fate of an extraordinary American manuscript in twelve books, produced by a Franciscan friar, preserved in the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana. Considered the first anthropological encyclopaedia of all time, within it the story of cocoa is recounted and illustrated, prompting us to reflect, starting with the historical approach, on those still sensitive aspects of the world of chocolate that are among the sustainable development goals of Agenda 2030: responsible consumption and production, environmental sustainability, social justice, eradication of poverty and an end to child labour and modern slavery.

Scientific and exhibition project

‘Cacao Entre Dos Mundos’ is a journey through time that begins with the collision of two worlds, from the moment when Admiral Cristoforo Colombo sighted a land never before seen by medieval westerners – ‘Mundus Novus’, as the Florentine navigator Amerigo Vespucci first called it. This unleashed a dramatic and historic clash of civilisations, culminating in the Spanish colonisation, following the tragic fall of the Aztec empire caused by the conquistadores led by Hernán Cortés.

The journey continues in the wake of the Spiritual Conquest brought about by expeditions of missionaries of the mendicant orders to the New World. Among them was ‘our’ Bernardino de Sahagún, a Franciscan, considered the founder of modern anthropology thanks to his magnum opus on the Aztec people, Historia general de las cosas de Nueva España, where the recipe for chocolate is transcribed for the first time.

We then retrace the arrival of cocoa in Europe following the so-called ‘Columbian Exchange’, together with the Medici family’s involvement in spreading the unusual beverage; we find scientific information on the organoleptic properties and the nutritional and therapeutic qualities of the precious fruit, the transformation of cocoa into chocolate, and the evolution of its processing and consumption over the centuries. Finally, the cocoa market is analysed, based on globalised pro-

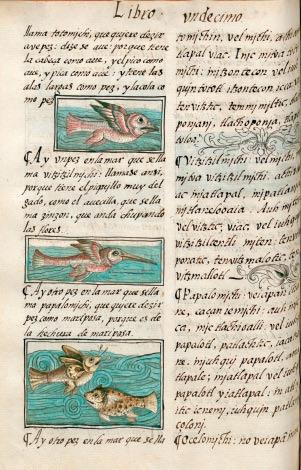

hummingbird Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Mediceo Palatino 220 16th century (1577) fol. 48v, detail

Mesoamerican cultures had a deep connection with nature and birds occupied an important role, symbolising concepts, taking on special meanings and religious values. They formed an essential part of their cosmogony, as they were considered the representation of certain deities. [r.V.]

Olmec Art, Hummingbird

Mexico, c. 200 BC

Olmec blue jade, 2.2 × 4.2 × 13.2 cm

Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Palazzo Pitti, Tesoro dei Granduchi, inv. Gemme 1911, no. 846

This is one of the very first indigenous objects to become part of the Medici Collection. It was identified in the inventories of the Medici ‘Guardaroba’ or collection in 1553 by historians Detlef Heikamp and Lia Markey. It is made of jade, a specific colour known as ‘Olmec blue’, and has the glassy appearance characteristic of this mineral. In addition to its long beak, one can identify the wings on the sides of the figure and above them, the eyes, drawn in a pair of circular shapes. The piece has a transverse hole on the slit dividing the bird’s head from the rest of the body, which is smaller in proportion. Visible behind and below the figure is a motif of two crossed bands, known as the St Andrew’s cross, a recurring motif on greenstone axes from the Mesoamerican Olmec region. It is likely that the hummingbird in the Medici Collection is an Olmec artefact from an offering of the Huey Teocalli (the Great Pyramid, or Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlán) recovered in the 16th century. The spirituality of the Mesoamerican peoples was expressed through the production of delicate jewellery, weapons and precious objects. In addition to obsidian, gold and the feathers of particular birds, the materials used included jade as a representative element of the tireless aesthetic quest to celebrate the beauty of creation through surprising light effects that marked Mesoamerican art for millennia. The expression ‘jade’ refers to minerals such as nephrite, a silicate of calcium and magnesium, and jadeite, a silicate of sodium and aluminium. This mineral – which the Spaniards nicknamed ‘piedra de ijada’ (‘stone of the hip’), due to its alleged benefits for kidneys and loins – is already archaeologically confirmed before 1400 BC, when it was used to make sharp axes for rituals. However, it was with the Olmec civilisation, which flourished from the 18th century BC onwards, that jadeite was heavily exploited, thanks to the lasting effect of their cultural action in the coastal area of the Gulf of Mexico, in the states of Veracruz and Tabasco, radiating even towards north-central Mexico and southwards in the present-day states of Oaxaca and Guerrero as far as Costa Rica. The crafting of minerals spread far and wide, eventually being particularly indicative of Mayan art as well. The artefact on display represents an ideal sample of the sophistication achieved by the Olmecs at the time of their slow and glorious political decline, which lasted until the 3rd century AD.

Found throughout the rainforests of the Mesoamerican tropics, where it originated and thrives in a variety of shapes and colours, this fascinating bird is able to adapt to a wide range of habitats. Geographically, today it can be found from Alaska to Patagonia, but its greatest diversity is concentrated along the Equator. The hummingbird family is a

Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Mediceo Palatino 220 Mexico, 16th century (1577) fol. 214v

With the Maya, cacao became the subject of many artistic items and artifacts. All manner of containers existed to preserve it, linked to ceremonies of daily life. The first written evidence of the use of the word cacao is attested to in the Classic Maya culture (which had learned about cacao from the Olmecs themselves, around 1000 BC). The glyph commonly used to write kakaw(a) is composed of three phonetic parts in which, according to Maya custom, the last vowel is silent.

Despite numerous studies on the subject, the cacao glyph still harbours many mysteries. In the numerous archaeological finds of cylindrical pottery that accompanied Maya nobles into the afterlife, a fish with two fins repeatedly appears. David Stuart, in Chocolate in Mesoamerica, offers one of the first technical explanations: the syllable ‘ka’, represented by a fin, takes its image from the glyph ‘kay’, fish, hence the writing of the word with the pictogram of a fish; thus the two fins are the repetition of the syllable ‘ka’, in twin syllables: ‘ka- ka-’; the last syllable of the glyph, ‘wa (ua)’, represented with a sort of shoot or sprout, takes on the meaning of ‘renewal’, completing the glyph ‘kakau(a)’.

The cacao ‘fish’ is directly linked to the tradition passed down in the Popol Vuh, the Maya-Quiché book of genesis, which recounts that the first cacao tree flourished when the heroic twins of the Ahpú dynasty, Hunahpù and Xbalanqué, rose from the primordial waters of the Underworld after passing through a stage as fish. These heroes of the Popol Vuh were presumably also the inventors of the processes needed to turn the fruits of the cacao tree into chocolate. Thus, the water twins lent their fins and wavy shape to the cacao glyph, by means of which the drink was elevated to the status of an elixir of resurrection.

For this reason, it can be asserted that the cacao tree grows, both in a real and a symbolic sense, in the shadows, concealing ancestral notions of death and resurrection. [l.h.–r.V.]

Q uautil

Al árbol donde se hace el cacao llaman cacahuacuáhuitl. Tiene las hojas anchas y es acopado. Es mediano. El fruto que hace es como mazorcas de maíz, o poco mayores, y tienen de dentro los granos de cacao; de fuera es morado, y de dentro encarnado o bermejo. Cuando es nuevo, si se bebe mucho enborracha. Y si se bebe templadamente refrigera y refresca. (‘The tree from which cacao is produced is called cacaoaquauitl: it has broad, cup-shaped leaves and produces medium-sized fruit, similar to corn cobs or slightly larger, containing the cacao beans. On the outside it is purple and on the inside it is flesh-coloured or vermilion. When young, if consumed in large quantities, it causes drunkenness; when consumed moderately, it has a cooling and refreshing effect’).

Bernardino de Sahagún, Mediceo Palatino 220, fol. 275r.

The Nahuatl term for the cacao tree is cacaoaquauitl. It is an evergreen that grows naturally in the tropical rainforest biome, in a belt stretching 20° north and 20° south of the Equator, with temperatures between 18 and 32 °C and precipitation between 1,500 and 2,000 mm per year. It grows protected in the shade of larger trees that shelter it from the sun and wind. It is a relatively small tree that reaches an average height of 6 metres. Depending on its size, there are four different names for it in the Nahuatl language: cuauhcacahuatl, the largest; mecacahuatl, xochicacahuatl and tlalcacahuatl, the smallest. At the time of the Mexica empire and the conquest, cultivation was limited to the specific geographical regions of its habitat, near the sumptuous aristocratic palaces and ceremonial centres of the cacao-producing cities.

Squirrels and monkeys (mainly the genus Ateles, mono araña) steal the pods to enjoy the pleasant-tasting white pulp which envelops the kernels, but avoid the beans themselves, thus contributing to their dispersal. ‘The monkeys cannot be seeking the beans, which are made bitter by alkaloids, but the delicious pulp, which is probably what attracted humans to T. cacao in the first place’ (Sophie D. Coe, Michael D. Coe, The True History of Chocolate, London, 1996, p. 22).

This tree belongs to the genus Theobroma, of the family Malvaceae. It has 22 species, of which only two are important for cultivation: Theobroma cacao and Theobroma bicolor. The species Theobroma bicolor, known as the ‘Macambo tree’, is used as a domestic plant and produces pataxte. The species Theobroma cacao produces the cacao fruit. Its initial wild distribution encompassed the vast regions of Mesoamerica and the northern and western portions of the Amazon basin, where it underwent an evolutionary process that led it to diverge into two distinct species:

1. Theobroma cacao from Amazonia. It produces hard, round fruits like small melons. It belongs to the ‘forastero’ varietal type and is a strong tree, highly resistant to disease and with a high yield of fruit. Its seeds are dark, very bitter and not very aromatic.

2. Theobroma cacao from Mesoamerica. It is distinguished by its long, pointed, wrinkled fruits with deep grooves. It belongs to the ‘criollo’ varietal type and is a delicate tree susceptible to disease, producing few pods, but its light-coloured seeds are very fragrant and not too bitter, with a very high-quality flavour and aroma. It was the species for which the rulers and nobles of ancient Mesoamerica had a particular predilection.

In the 18th century, the first Theobroma cacao hybrid was created on the island of Trinidad off the coast of Venezuela. A hurricane or disease caused the death of numerous trees of the ‘criollo’ varietal type previously planted in the area.

During the subsequent planting of ‘forastero’ trees to replace them, cross-pollination took place with the surviving ‘criollo’ trees, thereby giving rise to ‘trinitario’ cacao. [r.V.]

flor de cacao

As is often the case with tropical fruit trees, the cacao tree flowers mostly cauliflorously, that is, directly from pads on the trunk. The flowers, which are small and consist of five petals, are pollinated exclusively by tiny flies that thrive in this environment. Cacao flowers are rich in phenylethylamine (a chemical that naturally alleviates stress by stimulating the production of endorphins, responsible for the common feeling of well-being one gets when eating chocolate). Their perfume is also widely used industrially, due to the natural fragrance – described as a mixture of vanilla and tropical flowers – that they release at the moment of flowering.

It is estimated that only between 1% and 3% of the flowers subsequently develop into the fruit, which is commonly called ‘cabossa’ and often ignored because of its much more prized seeds. [l.h.]

Once the flower has been pollinated, the fruit develops: an elongated, ribbed pod called ‘cabossa’ or ‘cabossis’, which can measure up to 15–30 cm long by 8–10 cm wide. It grows directly on the trunk and its colour varies from yellow-green to red-brown, depending on the stage of ripeness. Each cabossa contains 25 to 40 almond-shaped seeds, called cacao beans, which are embedded in a sweet, gelatinous white pulp called mucilage.

In plantations, men have to pick and open the fruit to obtain the cacao beans. It is essential that harvesting is done with great care and attention, so as not to damage the pads that produce flowers and thus fruit. The harvest takes place twice a year, usually between November and January and between May and July. [l.h.]

Once the cacao pods have been opened and the fruit extracted, there are four main steps in cacao processing: fermentation, drying, roasting and decortication.

No matter what the level of technology, this sequence has been in force for at least three millennia, and still is followed in the modern world.

Sophie D. Coe, Michael D. Coe, The True History of Chocolate, London, 1996, p. 23.

The fruit removed from the cabossa consists of cacao beans and the pulp that envelops them. This is then gathered, placed in piles directly in the harvest area or, in certain circumstances, in stacked wooden crates. This starts the spontaneous fermentation process, which can last from three to five days. From the first day, chemical and biological processes are activated. The pulp amalgamates with the seeds and becomes liquid, then there is a short germination phase followed by the rapid death of the seeds, caused by high temperatures and increased acidity. This phase gives the beans their characteristic chocolate flavour. Around the third day, the seed mass, which has to be turned from time to time, is between 45 and 50 °C and must remain at this high temperature for a few days in order to facilitate the absorption of the flavour acquired during germination.

Once fermentation is complete, the beans are dried traditionally on mats or trays left out in the sun, which takes one to two weeks, depending on the weather conditions. The enzymatic action triggered during fermentation is not interrupted during the drying process, during which the cacao beans lose more than half their weight.

Since the cacao beans are always of different shapes and sizes, it is important to select them so that they have a similar size within each roasting batch in order to ensure uniformity during the process. Roasting, which lasts between 70 and 115 minutes, takes place at temperatures ranging from 99 to 104 °C. During this phase, the beans take on a more intense shade of brown, become crumblier and lose their astringency. This is an essential step for the development of the required flavour and desired aroma.

The final step in obtaining processed cacao is to remove the husks that envelop the beans. Once this process is complete, the cacao is ready to be processed to produce chocolate and its myriad variations. [r.V.]