Charley Toorop Love for Van Gogh

Foreword

Benno Tempel

Encounters with Van Gogh

Charley Toorop

‘It has always remained an event to see his work’

Charley Toorop’s fascination with Vincent van Gogh

Renske Cohen Tervaert

From Borinage to pilgrimage

Vincent van Gogh and Charley Toorop in the Pays Noir

Franka Blok

Art as medicine

Charley Toorop and the desire for a more humane society after the First World War

Marjet Brolsma

Charley Toorop at the Willem

Arntsz Foundation

Wessel Krul

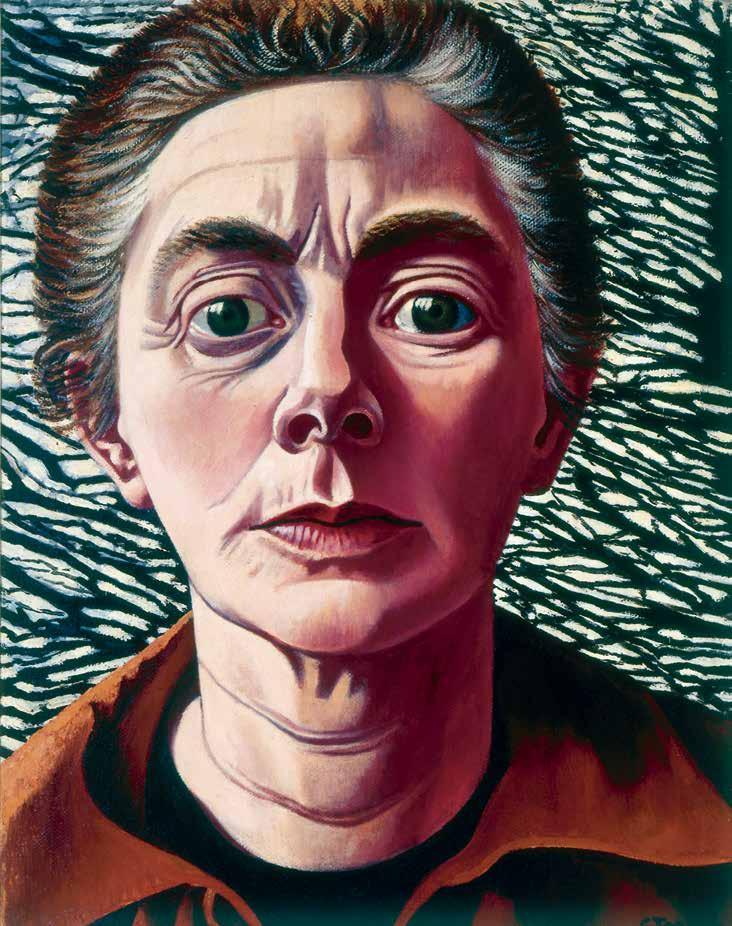

Cat. 6 Self-Portrait with Winter Branches, 1944-1945

Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven

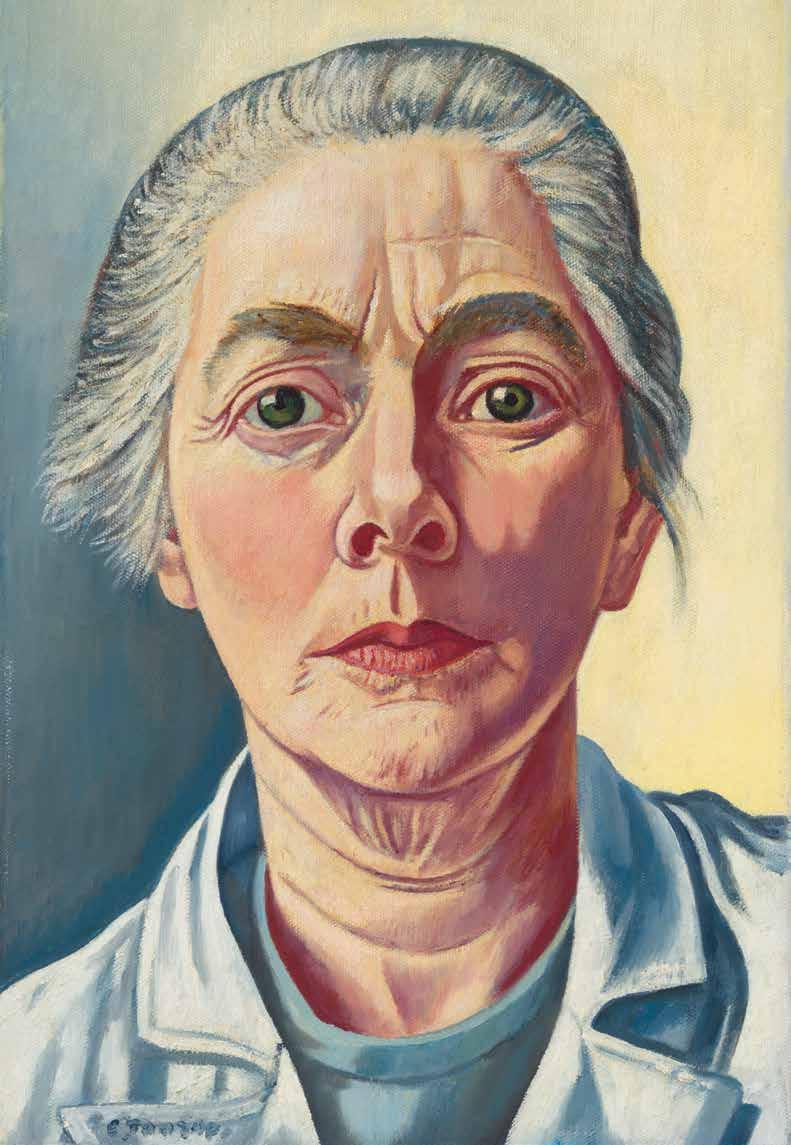

Cat. 7 Self-Portrait, 1953-1954

Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

Cat. 13 Montrouge Cemetery, 1920

Private collection

Cat. 14 Place de la Contrescarpe, Paris, 1921 Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

Cat. 21 The Hostess and Her Daughter, 1922 Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

Cat. 22 Two Miners’ Wives in the Borinage (Lia and her Mother), 1922 Museum Helmond

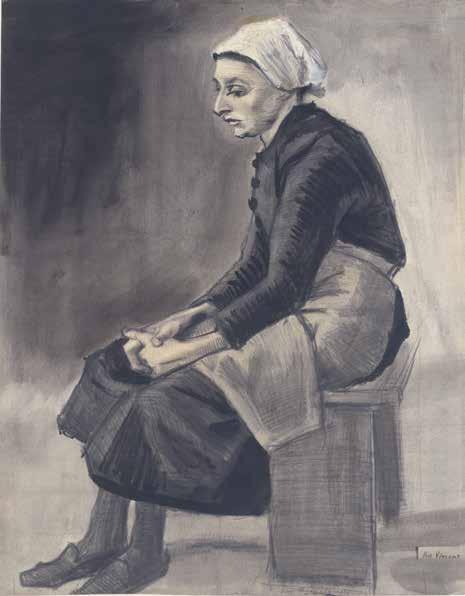

16. Vincent van Gogh, Woman Seated, The Hague, April-May 1883, pencil, grey wash, brush in (printing) ink, oils, and traces of squaring on wove paper, 56.3 × 44.1 cm Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

Van Gogh’s popularity remained undiminished in the 1920s, as evidenced by both the number of exhibitions and the constant praise from critics, such as [Van Gogh is] ‘the noblest genius in half a century’ and ‘we have not had such a great and complete artist in painting since the 17th century’. 33 It is noteworthy that the image of Van Gogh created early on, as an artist embroiled in a personal struggle, sensitive to harsh realities and human suffering, was maintained unabated. This is evident from various exhibition reviews. For example, in De Telegraaf in 1919, Bergen School artist and art critic Kasper Niehaus (1889–1974) compared the drawing The Bearers of the Burden (1881) [fig. 13] to a ‘modern “via dolorosa”’ of ‘a procession of the damned weighed down by the burden of suffering’, created by Vincent in ‘such a difficult but beautiful time’. 34 And in 1929 the NRC noted that Van Gogh’s work evoked the image of the ‘struggling man, who has experienced human misery’. 35 This prevailing image must have appealed strongly to Toorop, with her interest in her fellow human beings and her ‘obsession with reality’.36

Toorop in Van Gogh’s footsteps

Toorop undertook her pilgrimage to the Borinage in the autumn of 1922. She stayed in the mining region from September to early October and found accommodation in Cuesmes, the town where Van Gogh had also lived, with a miner’s wife and her

daughter.37 Unlike Van Gogh’s two-year stay in the mining region, little is known about Toorop’s time there. Only a single letter of hers has survived, while Van Gogh left ten long letters.38 According to art critic Bram Hammacher, Toorop walked for hours on end through the black industrial landscape – possibly a romanticisation on his part, but likely not far from the truth given her penchant for long walks.39 Although Toorop had travelled to the mining region out of interest in Van Gogh, her interest would equally have been aroused by the images that socialist painters had captured of the region after Van Gogh’s time there. As one of the most industrialised areas in Europe, the Borinage in the late nineteenth century was the ideal location to depict the laborious struggle of the worker.40 Her own father was one such artist: in 1886 Jan visited the region and chronicled a major miners’ strike in several paintings [fig. 17] . 41

Charley made drawings and paintings of both the miners and the surroundings during the few weeks she stayed there. In Street in Cuesmes we see features that Van Gogh mentioned in his letters and depicted in his first drawings: a winding street with small houses, smoking factory chimneys and towering slag heaps, the so-called terrils [cat. 19] . Toorop’s drawings in particular are reminiscent of Van Gogh in their atmosphere and subject matter, especially his figure studies of working-class types from The Hague [fig. 16] . As is the case with Van Gogh, Toorop’s drawings focus on the figure, the faces have worried, tired expressions, black is dominant and there are strong light-dark contrasts [cat. 17] . Nevertheless, her style and technique are quite different: the lines are more systematic and angular, the figures more grotesque, the whole more tidy. She seems above all ‘inwardly related’ to Van Gogh, as Hammacher aptly remarked.42 With Van Gogh in mind, she had travelled to the Borinage to give her own unique interpretation of the life she encountered there. And in that she succeeded, as her own words show: ‘Thank God it is now gradually beginning to emerge what I can what I want to express without any separate beauty [...] the beauty of the inner that is inexpressible [...]’.43 And not unimportantly, with her trip she responded to Van Gogh’s deeply cherished wish for other artists to also document life in the mining region.44

Writing pilgrims

It appears that Toorop was not unique in her Van Gogh pilgrimage. When free travel across Europe became possible again after the First World War, there were others who planned to follow in Van Gogh’s footsteps. The publication of his letters in 1914 had made it possible to closely follow Van Gogh’s travels across the European continent. Some Van Gogh-loving writers took advantage of this and conducted thorough and, moreover, ground-breaking research in situ to get as close to the artist as possible: the houses where Van Gogh had lived were visited, the local area explored, and the people who had known Van Gogh personally were interviewed. One of the first was Louis Piérard (1886–1951), a Belgian Socialist politician and, not unimportantly, the grandson of a miner. Already in the 1910s, he followed Van Gogh’s trail in the Borinage and made important discoveries there.45 For example, he found miners who had witnessed Van Gogh drawing, as well as the cottage of the Denis family in Wasmes with whom Van Gogh had lodged. The research resulted in the detailed article ‘Van Gogh au Pays Noir’ in 1913 and, after further research, which also included the 1914 letters edition, in the biography La Vie tragique de Vincent van Gogh in 1924.46 In September 1925 a Dutch newspaper reported that a memorial stone had been mounted to the facade of the Denis family’s home in honour of Van Gogh, exactly three years after Toorop made her pilgrimage.47

17. Jan Toorop, Morning (After the Strike), c. 1888-1890, oil on canvas, 65 × 76 cm Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

Cat. 24 St. Paul and the Mountains, 1923 Kunstmuseum Den Haag

Cat. 32 The Family, 1920 Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

Cat. 33 Peasant Family in Zeeland, 1927

Stedelijk Museum

Amsterdam

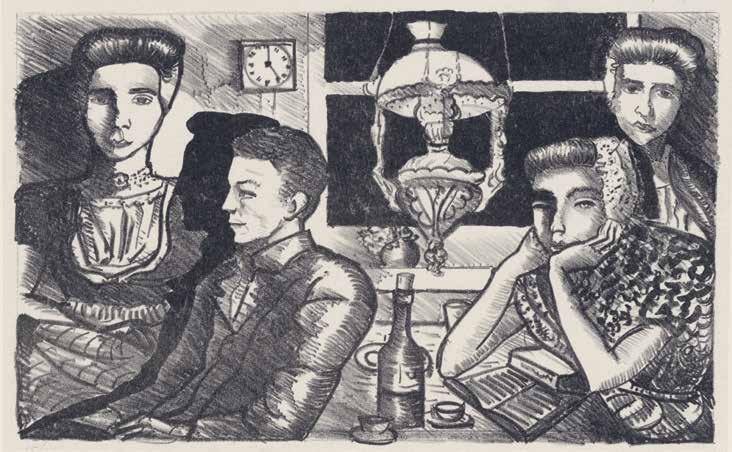

Cat. 39 Four Walcheren

Figures in an Interior, c. 1929

Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

Cat. 40 Three Walcheren

Figures in an Interior, 1929

Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

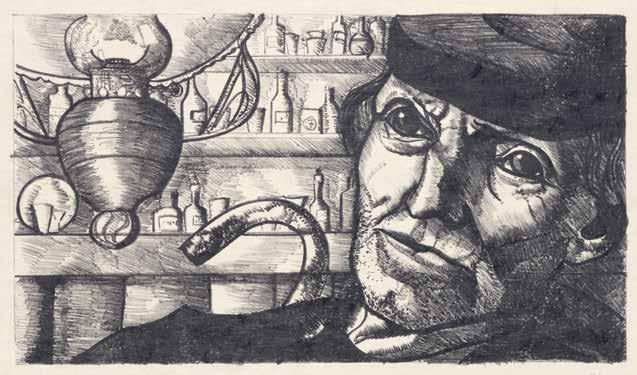

Cat. 41 Farmer in a Tavern, Westkapelle, 1931

Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

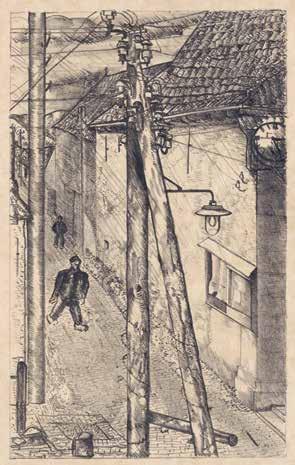

Cat. 42 Lane in Westkapelle, 1930

Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

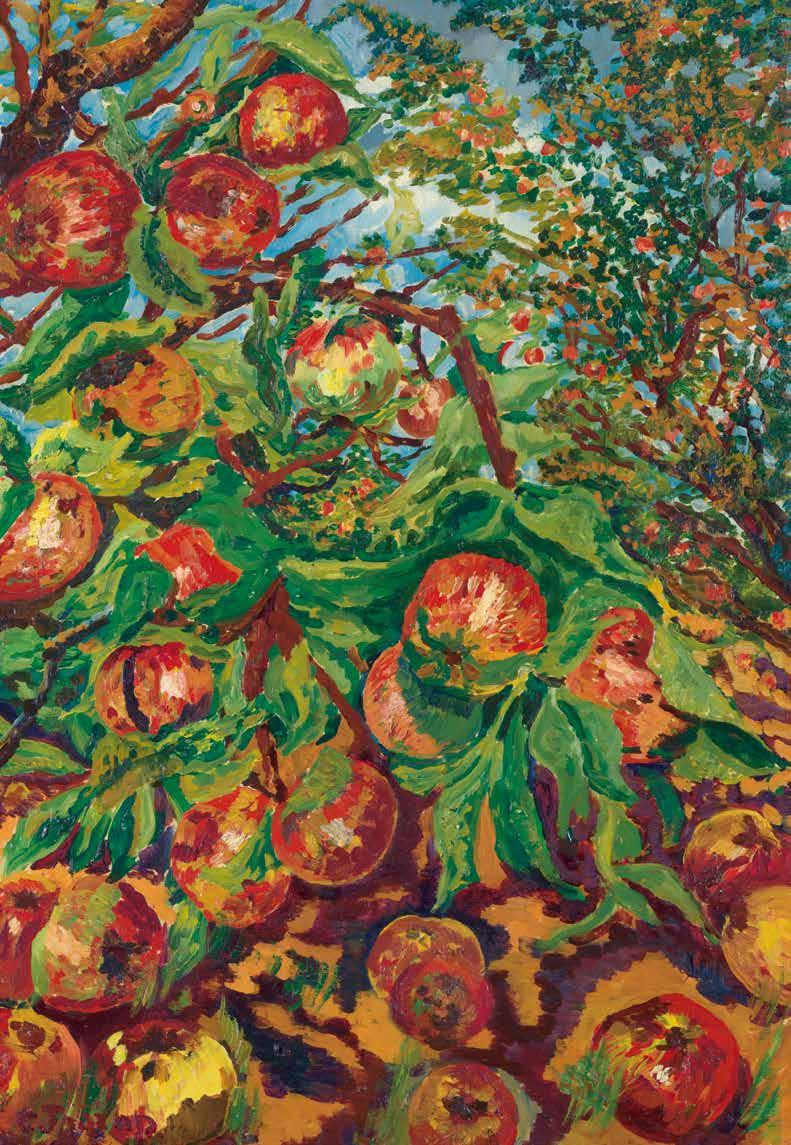

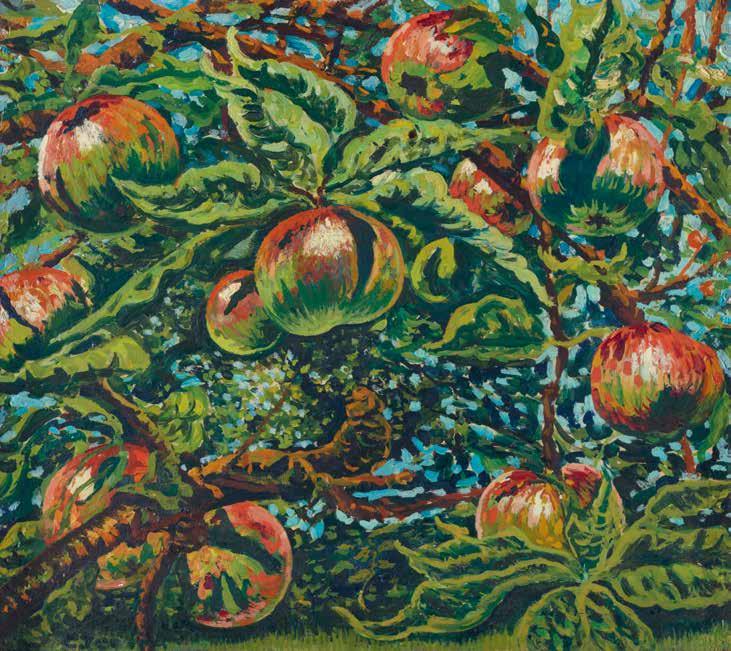

Cat. 62 Autumn, 1950

Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

Cat. 63 Apples in the Sun, 1945

Cat. 66 Group Portrait of H.P. Bremmer and His Wife with Contemporary Artists, 1935-1938

Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

Charley Toorop’s work has an originality and power all its own. However, there is one artist who she believed stood at the cradle of her artistic practice and whom she subsequently respected throughout her life: Vincent van Gogh. For her, his work was ‘the breakthrough to a new world’. In four essays her fascination is outlined. Among the topics discussed are her travels to the Borinage and southern France, where she sees the landscape and people through Van Gogh’s eyes and her respect for Van Gogh’s ‘deep harsh love of reality’.