There is nothing to indicate that Edvard Munch had a different relationship with chairs than most of us do. Even today, when many of us spend too much time sitting down, both voluntarily and involuntarily – which also links chairs to a growing health problem – the chair is still one of society’s most widely used pieces of furniture. The chair, in its many shapes and forms, helps us through the day, from the breakfast table to a cozy evening in front of the TV. There are also chairs for specific needs, such as high chairs, wheelchairs, deckchairs and rocking chairs, but most are quite versatile. Chairs tend to be easy to move and take with you, both around the house and throughout life. Most are not least relatively easy to get rid of, should one wish to do so. As well as having practical qualities, a chair can also be of emotional importance to its owner. And it is this emotional dimension that I want to explore here, based on an old wicker chair that Munch owned.

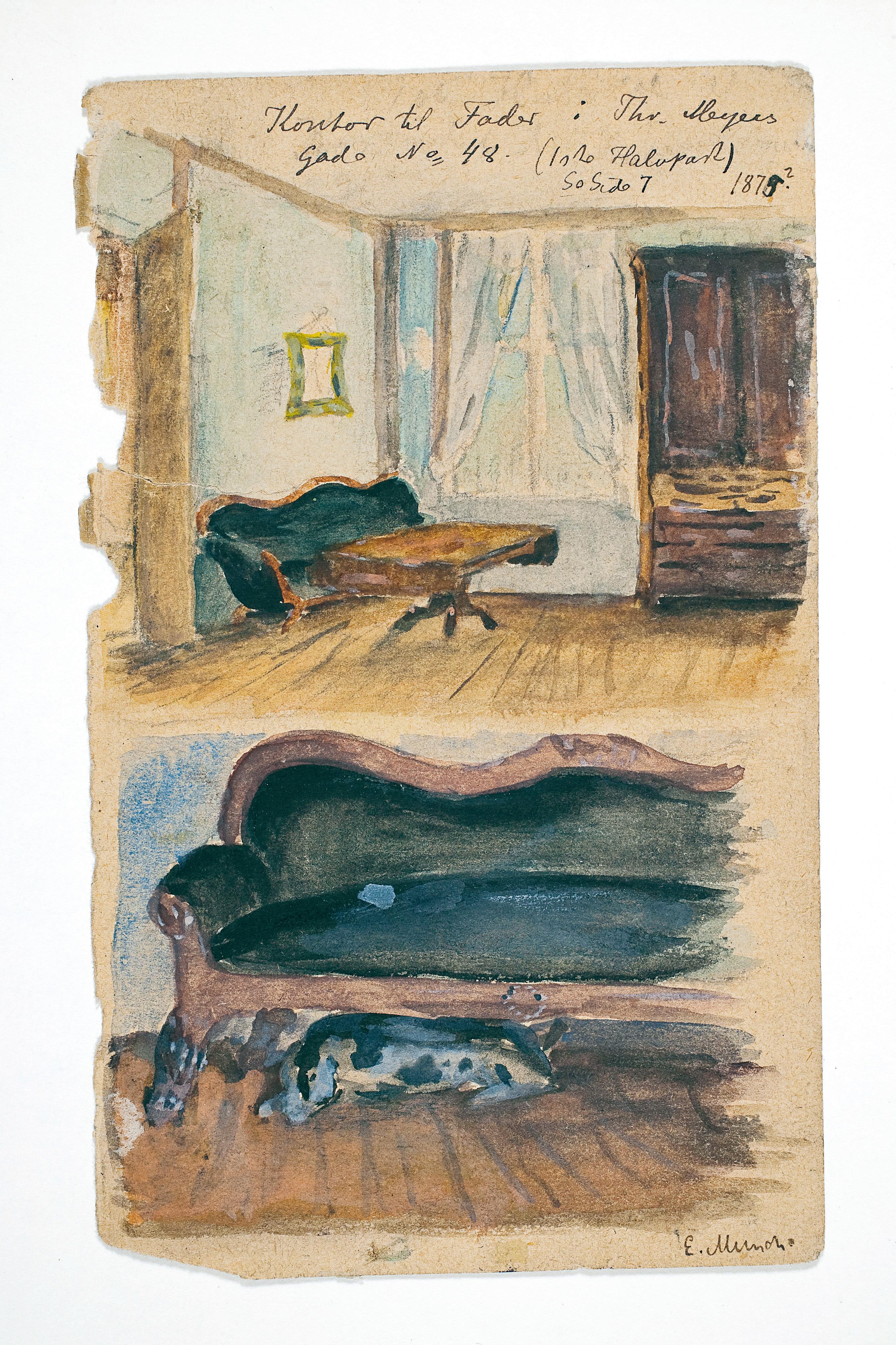

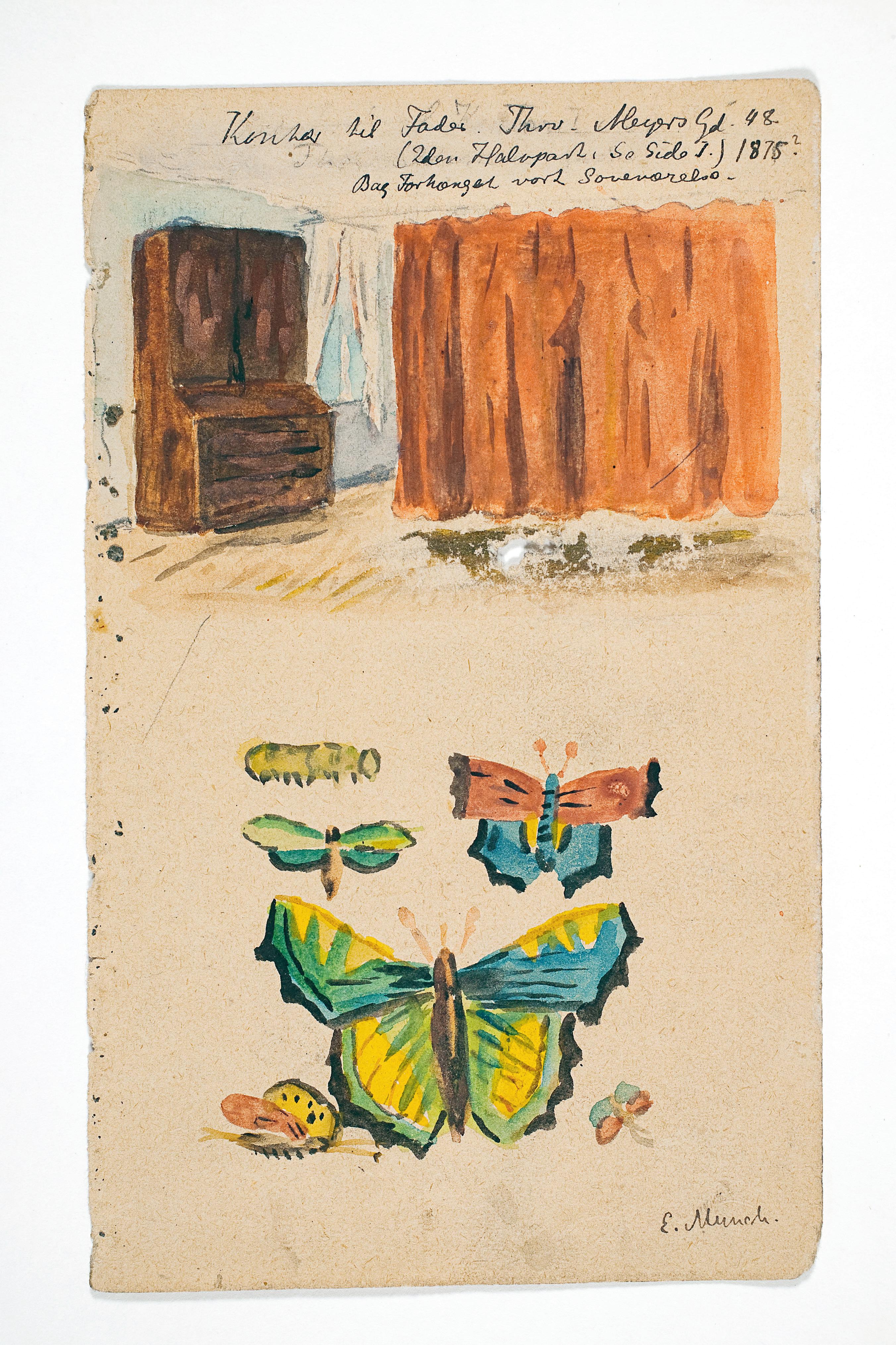

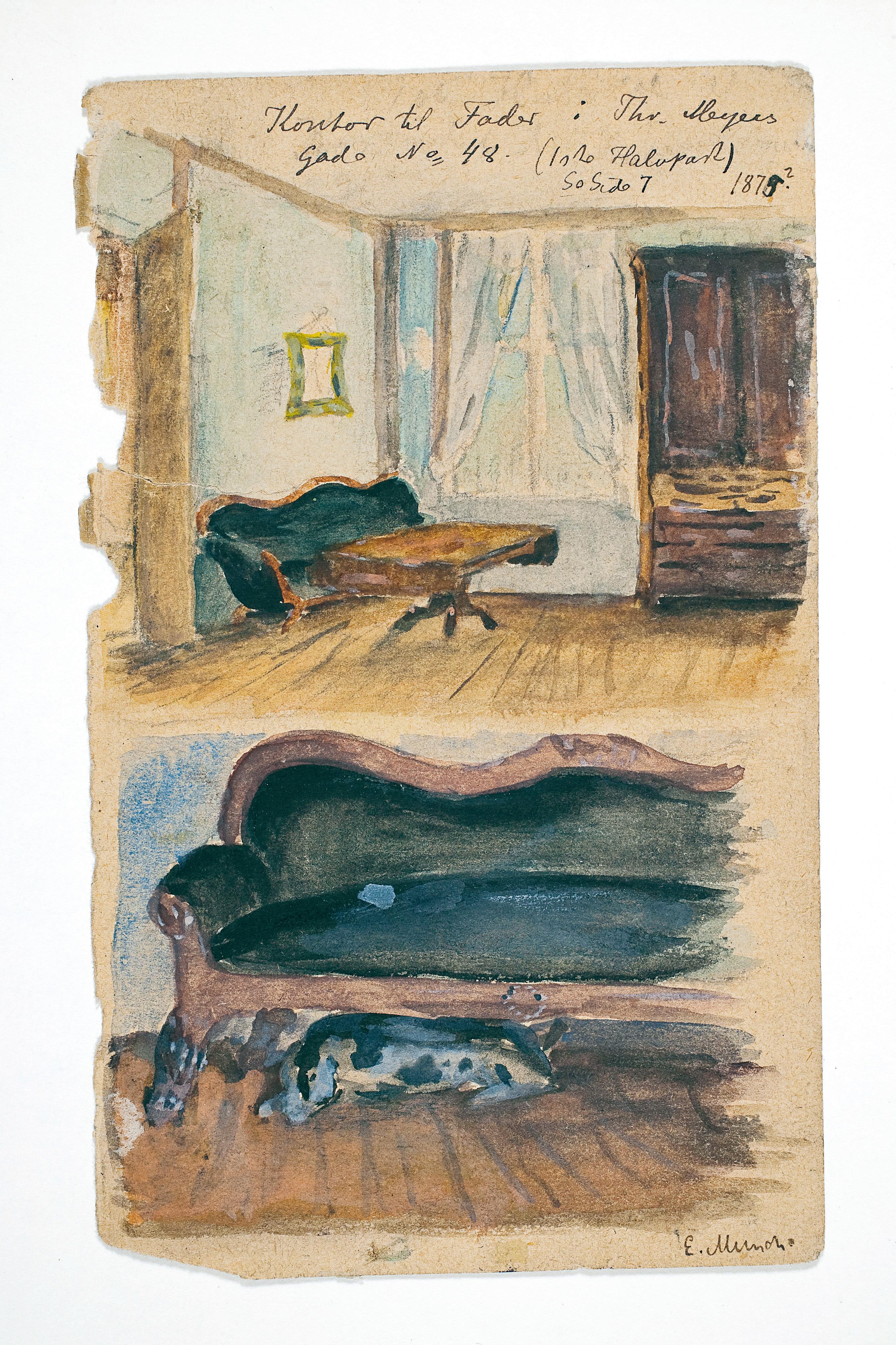

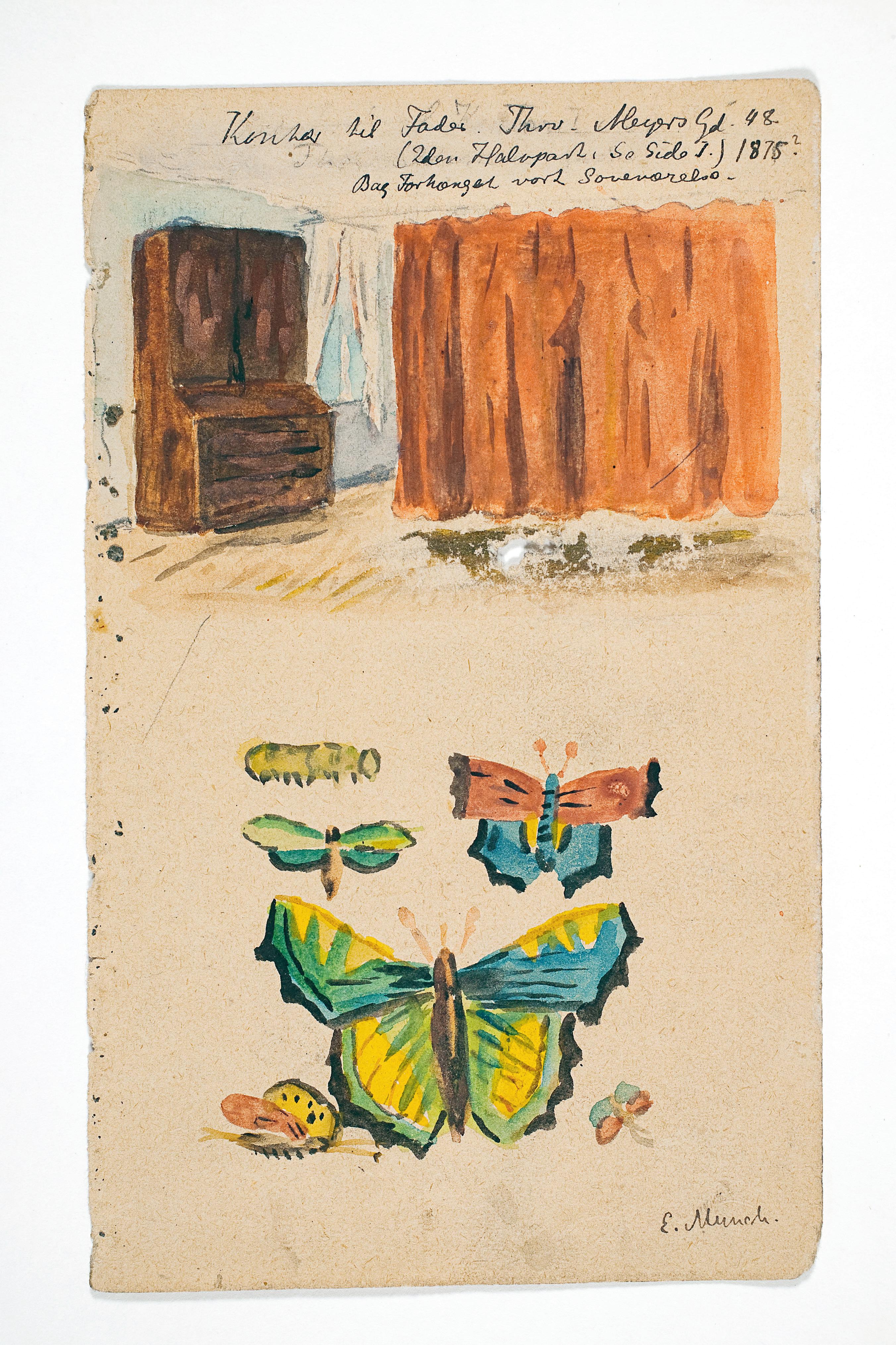

The City of Oslo received Edvard Munch’s collection of artworks in 1944, as a testamentary donation from the artist. At the same time, thanks to an initiative from his sister Inger Munch, a range of objects and items of furniture from his estate were selected to be preserved in what would become Munchmuseet.1 We don’t know the exact selection criteria involved, but it is most likely that these objects – including eleven chairs and a sofa – were chosen either because they had been depicted in Munch’s art or because they played a special role in his life, or both. One of the items preserved is a striking and elegant neo-rococo wicker chair, made in the 1860s and probably out of willow. At that time in Norway, such chairs and other types of wicker furniture were made by professional wicker-workers or local artisans, most likely inspired by those from central Europe.2 Wicker furniture was also especially popular in England around 1860–80, the reason being that it was – as it still is – beautiful, lightweight, practical, comfortable and affordable.

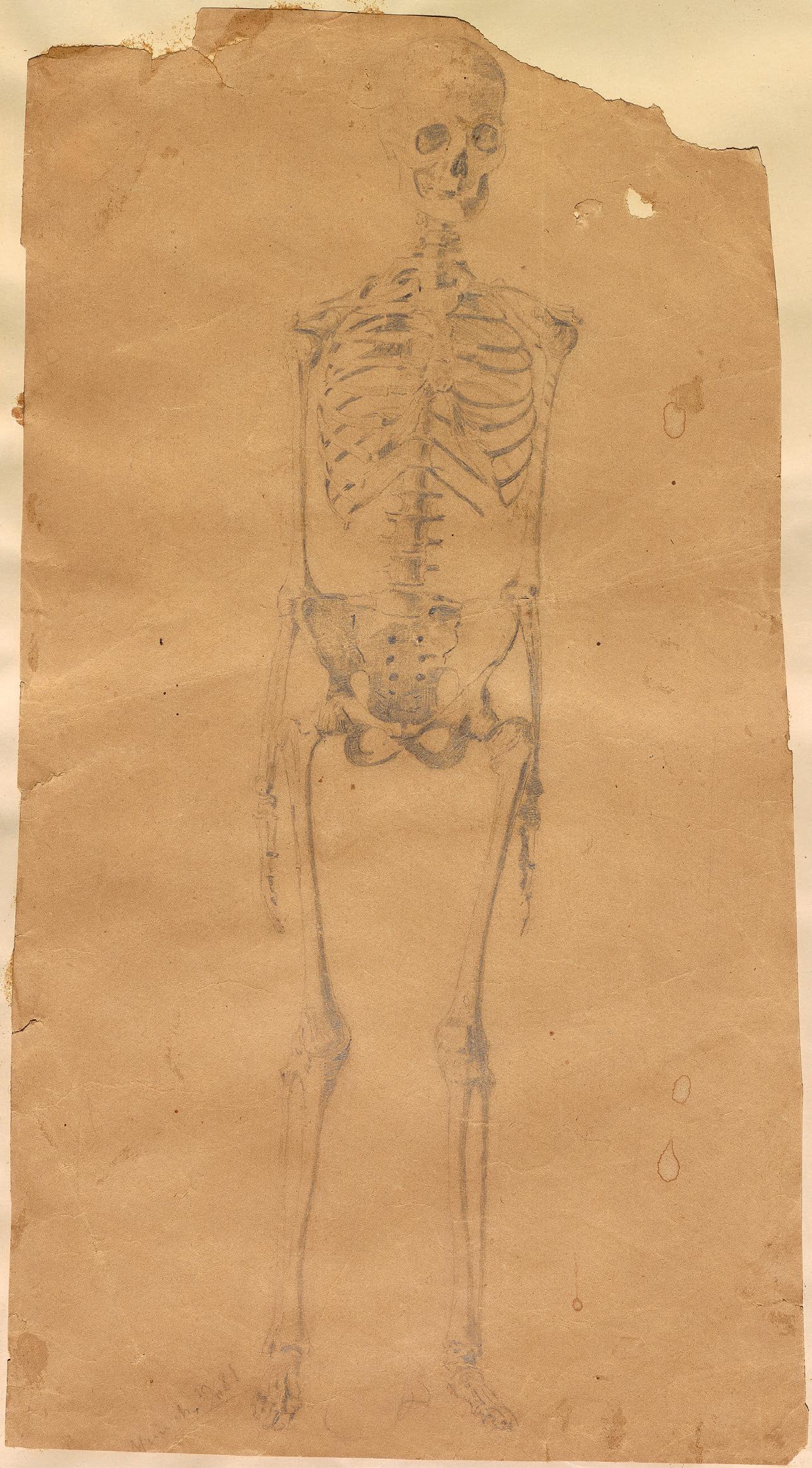

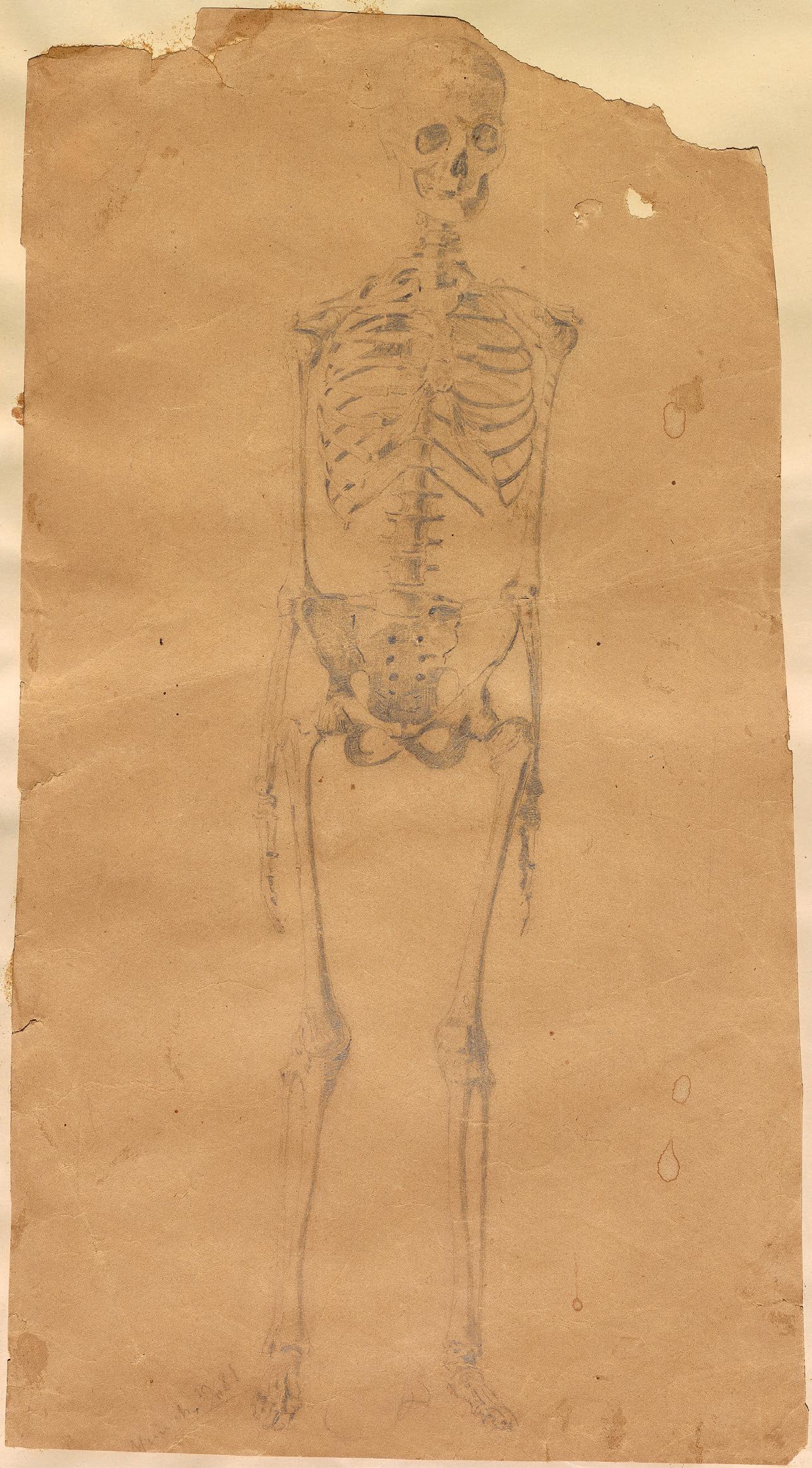

also, from his childhood, the imperative to care for himself: ‘… we knew about the chest diseases that threatened us … I must always watch after myself – I felt as though I was doomed’.8 His lifelong self-scrutiny and self-care were practical matters, protecting the smooth functioning of his vulnerable lungs.

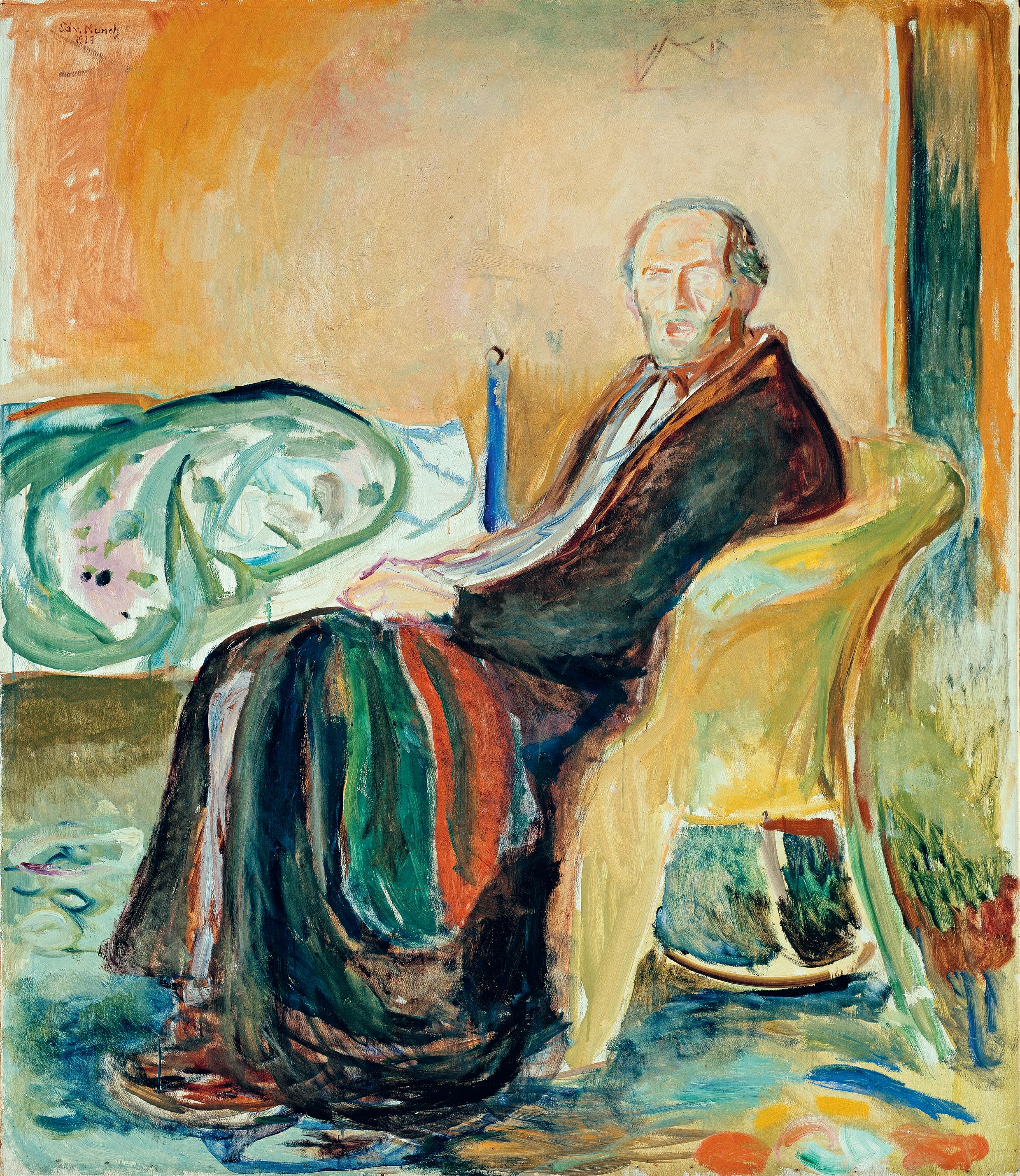

Munch had a history of exhibiting self-portraits that represented bodily insecurity. In 1899, he had travelled to Italy, in part seeking relief from a lung ailment, only to suffer throughout the entire journey. A physician in Switzerland recommended that he receive ‘absolute rest’, and he selected Kornhaug Sanatorium, a high-mountain retreat in Gausdal, Norway, where he spent the turn of the years 1899 into 1900.9 There he painted Golgotha, the scene of crucifixion that is often identified as containing two self-portraits, one as the suffering, vitiated body of Jesus and another in a crowd of people compressed below the cross. Above the red cloud weaving its way across the explosive sky, Munch signed his name and added ‘Kornhaug Sanatorium 1900’, announcing his therapeutic site on the surface of the painting. The unusual gesture of locating a crucifixion at a sanatorium, as I have argued elsewhere, was a means for the artist to stake an identity as a poète maudit (accursed poet) embodying a discourse of creative suffering.10

In 1909, as the artist planned his departure from Dr Daniel Jacobson’s clinic in Copenhagen, he likewise painted a selfportrait on the surface of which he inscribed the place name and year, ‘Kjøbenhavn 1909’.11 As his admission to the clinic had been fodder for the popular press,12 the vibrant painting announced a resurrection.13 Munch exhibited these paintings shortly after each was completed so that his audiences might associate his image and identity with that of physical debilitation as well as the sites and dates of treatment and

possibly of cure. These paintings offer the most intimate self-scrutinies, tokens of creative suffering and explorations of pathologised identity that extended throughout Munch’s writings and material practices.14

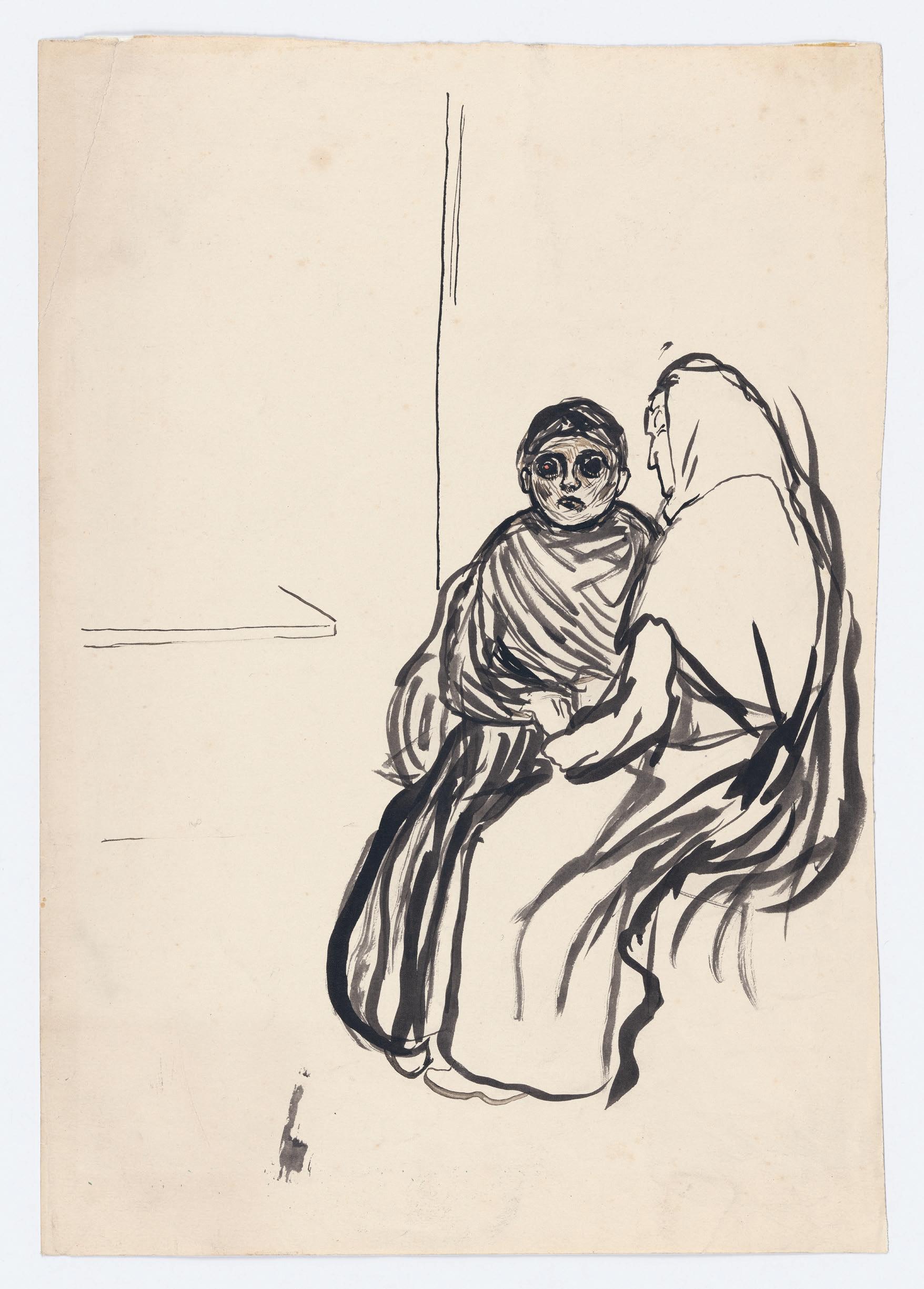

The Spanish Flu likewise hovers between self-scrutiny and public declaration Munch’s image identifies his studio as his sickroom, a privileged place for the most intimate and abject of bodily disclosures.15 There are no medicinal preparations present, as in earlier renderings of sickrooms, such as The Sickroom (p. 246) and The Sick Child (p. 162), and no representations of hallucinations or shadows as in By the Death Bed (p. 248) and By the Death Bed. Fever (p. 249). Unlike those paintings, there is no one present to observe or minister to the figure. Rather, Munch pictures the fearful isolation imposed by contagion and the lonely self-care demanded of isolation. In the wake of the bacteriological revolution of the later 19th century, when the germ theory of disease transmission was increasingly accepted, the hygienic measure of isolation was a critical means of disease control. Invisible to the eye, germs were ‘uncontrollable and unknowable’,16 threatening the integrity of the body. In addition to protecting the body’s boundaries, isolation was a means of caring for the community, prompting a culture of hygienic vigilance around social interaction.17

In 1890, while the deadly ‘Russian’ or ‘Asian’ flu pandemic swept through Paris where Munch was then residing, his aunt, Karen Bjølstad, wrote to him, musing about the implications of Robert Koch’s theory of germ transmission for their often stricken family: ‘Dr Koch’s discovery probably interests all of Paris and, – I think it is strange that such news does not bring joy to everyone it concerns – for example, each of us’.18 Himself ill, the artist sought isolation in the suburb of Saint-Cloud.19 There he painted the first version

There is an undefinable point where the body ends and the world begins, and I write undefinable because there is a hazy borderland between the two, between the body and the world. I also think that point, despite everything, is the right word because what I’m writing about is a meeting point between what’s me and what isn’t, a place where something collides with something else, where identity is formed.

For me this point can be on my skin, at the very tip of a finger, but it can also be in the basket behind my wheelchair, when it bobs up and down because some party-guest found it convenient to lean on while having a casual chat. It’s not obvious to him that what he’s doing is intimately uncomfortable for me, but it is. The vibrations from the bobbing basket pass through the wheelchair’s inanimate matter until they are felt in my living body, and I then realise how much I depend on this mobility aid to do so many things. If the basket falls apart or one of the headlamps breaks it’s like my actual body is damaged, it’s like twisting your elbow or getting a stye in your eye.

I write mobility aid, and this word alludes to a certain form of vulnerability, to bodies that don’t move well in the world without the aid of specific objects. But words and categories can be misleading, because the same vulnerability can be felt when I can’t find my glasses or my cellphone. The word I’m looking for is prosthesis, it embraces the intimate and strange relationship between the body and these things which are so much more than things, which shape and are shaped by the senses and carry so much meaning.1

In grammar, there is a distinction between common nouns and proper nouns, but the objects we call mobility aids nearly always deserve proper nouns. The wheelchair I use every day is a Permobil, it is the Permo, and is so irreplaceable that it’s not just an object, it is almost a subject, a partner, somewhere between a draught animal and a member of the

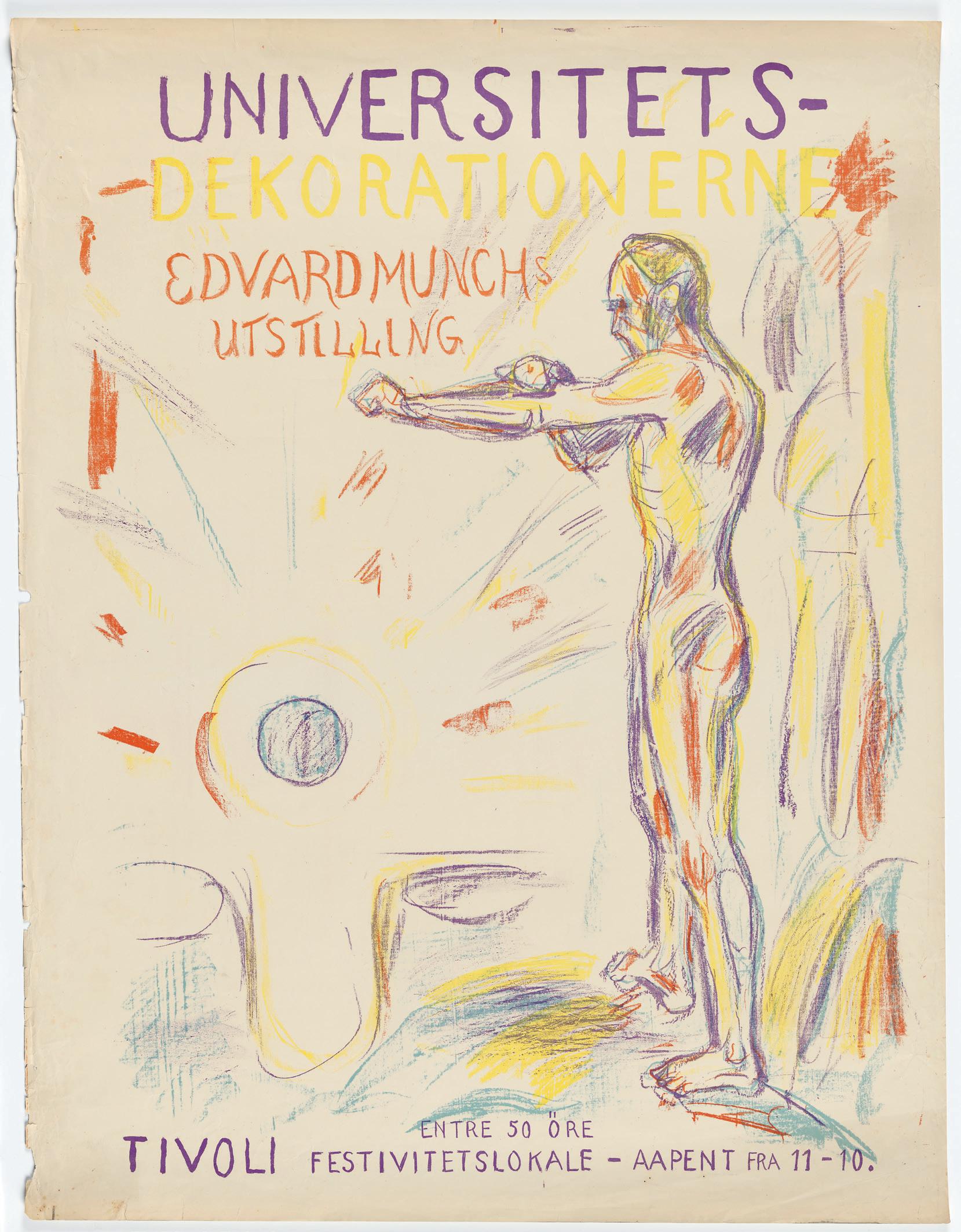

Published by MUNCH on the occasion of the exhibition

Lifeblood – Edvard Munch

27 June – 21 September 2025

Head of MUNCH Publishing: Josephine Langebrekke

Editor and curator: Allison Morehead

Editor: Heidi Bale Amundsen

Editorial consultant: Karen Elizabeth Lerheim

Translations from Norwegian by Matt Bagguley: Texts by, and authors’ biographies of Hege Duckert, Signe Endresen, Aurora Hoel, Jan Grue, Ute Kuhlemann Falck, Cathrine Knudsen, Cathrine Krøger, Olaug Nilssen, Kaveh Rashidi, Thorvald Steen, Sara Stridsberg, Espen Stueland and Ingvard Wilhelmsen

Design: Øystein Arbo studio Typeset in Trinité by Bram de Does

Repro: JK Morris

Print and binding: Musumeci SpA, Italy

Cover: Edvard Munch, On the Operating Table, 1902–03

All rights reserved. This book’s contents may not be reproduced in any form, in whole or in part, without written permission from the publisher.

© 2025 Munchmuseet, Oslo www.munchmuseet.no

ISBN : 978-82-8462-053-4

MUNCH thanks its sponsors and partners: