Carte di Castello 4

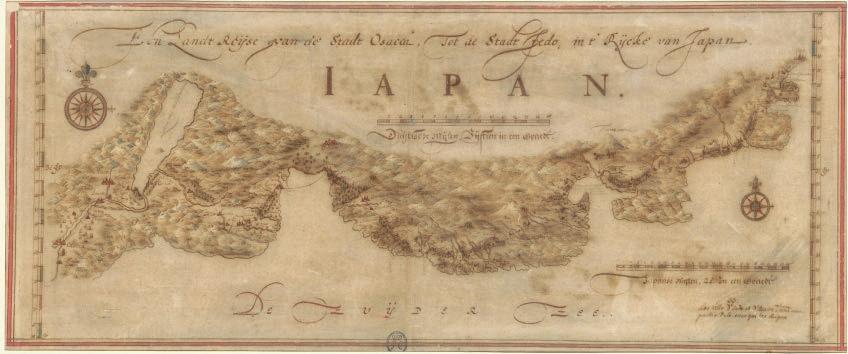

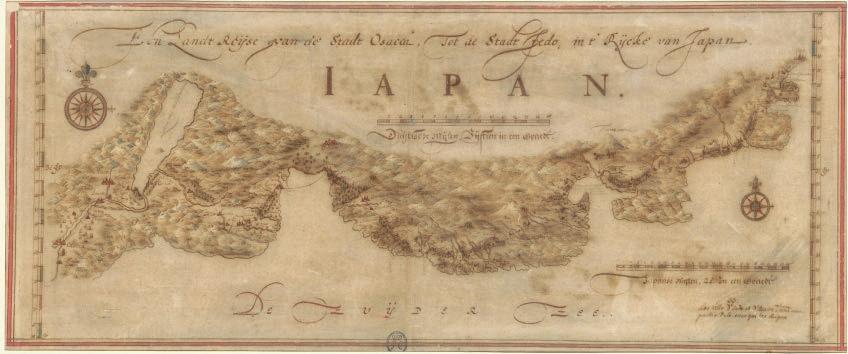

Een Landt Reijse van de Stadt Osacca, Tot de Stadt Jedo, in ’t Rijcke van Japan | IAPAN

Overland route from the city of Osaka to the city of Edo [Tokyo] in the Kingdom of Japan | JAPAN

Attributed to Johannes Vingboons and his workshop

Amsterdam, c. 1660–8

Line-and-wash drawing on canvas-backed paper, 81.8 × 34 cm

Ownership stamp of Peter Leopold, grand duke of Tuscany; inventory record: ‘33. Les ville [sic] d’Jedo et d’Osacca au Japon, avec une partie de la mer qui les baigne’.

Other copies

Van der Hem, 41:26.

Selected bibliography

Wieder 1925–33, IV, p. 133, no. 65; Van der Krogt 2005, p. 400; Gosselink 2007, p. 150, no. 231.

Carte di Castello 4 and 5 form a cartographic diptych of Japan, painting a highly detailed picture of the coastlines of the islands of Kyu¯shu¯ and Honshu¯ and showing the land and sea routes from Nagasaki to Edo (present-day Tokyo) passing through Osaka and Kyoto. The route illustrates the main stops on the jour-

ney that the Dutch, despite officially being confined to the small island of Dejima, in the bay of Nagasaki, were required to make periodically to pay homage and tribute to the Tokugawa shoguns. The path partly coincided with the To¯kaido¯ , namely the journey of servitude from Kyoto to Edo, made by the Japa-

nese daimyo¯ themselves to pay tribute to the shoguns.

The Dutch, called ko¯mo¯jin or ‘red-skinned men’ by the Japanese, arrived in Japan in 1609 and opened a warehouse on the island of Hirado, in northern Kyu¯shu¯. Unlike the nanbanjin (Portuguese merchants), who had arrived in

1543 and were expelled from Japan in 1639, and the missionaries, especially the Jesuits, expelled in 1614, the ko¯mo¯jin, who were only interested in trade and had no missionary ambitions, were permitted to stay during the sakoku, that is to say Japan’s isolation following the expulsion of the Portuguese and Spanish. The

Dutch were the only westerners in Japan until 1865, when the Meiji era began.

Catalogue raisonné of the

Carte di Castello 7

Taÿoan

Anping, Taiwan

Attributed to Johannes Vingboons and his workshop

Amsterdam, c. 1625–60

Line-and-wash drawing on canvas-backed paper, 89.7 × 53.5 cm

Ownership stamp of Peter Leopold, grand duke of Tuscany; inventory record: ‘35. Plan du bourg et die fort de Tayoan’.

Situated between the south-western coast of present-day Taiwan – the ancient Formosa, namely the ‘beautiful’ island, as the Portuguese called it in around the mid-16th century – and the continental coast of China, the city-peninsula of Taÿoan was a strategic commercial stopover on the way to Ming China (1368–1644). When the Dutch were forced to leave the nearby island of Penghu in 1623, they moved to Formosa and the Dutch East India Company built an imposing fortified warehouse there, which acquired its definitive name of Fort Zeelandia in 1653 and was previously referred to as Oranje, Fort Formosa and Provintia. With the advent of the Qing dynasty in 1644, the Manchurian Chinese occupied Taiwan and annexed it in 1683. The impres-

sive Zeelandia fortress (5) occupies a central position on the map. It is defended by imposing bastions (7), together with the fleet of fluyt (literally ‘flute’), the ships specifically designed and built by the Dutch for transoceanic voyages. As well as being able to carry a considerable amount of cargo, they were also fitted with fifteen guns and were easy to build and maintain. In addition to the fluyt, there are also numerous smaller vessels in the harbour, which were used for local trade. Towards the bottom of the map we can glimpse a Dutch captain meeting a Chinese official (10). The bird’s eye view of Taÿoan forms a cartographic diptych with the nautical chart of Formosa (CdC 14).

[AC]

Other copies

BNF, 27 (5)-P187914; Van der Hem, 41:05.

Selected bibliography

Wieder 1925–33, IV, p. 132, no. 60, V, p. 174; Van der Krogt 2005, p. 374; Gosselink 2007, pp. 87, 150, no. 218; Atlas of Mutual Heritage, s.v.

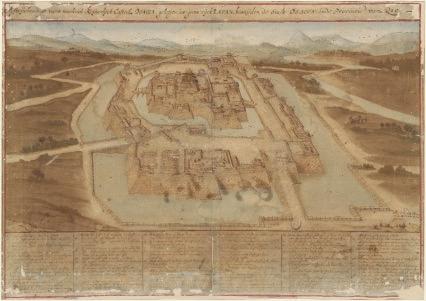

Carte di Castello 8

Afteijckeninge vant machtich

Keijserlijck Casteel OSACCA. geleegen int groot rijck IAPAN. besuijden de Stadt OSACCA. inde Provincie van Qio

Drawing of the formidable imperial castle [of] Osaka located in the great Kingdom of Japan, south of the city of Osaka, in the province of Kyoto

Attributed to Johannes Vingboons and his workshop

Amsterdam, c. 1665

Line-and-wash drawing on canvas-backed paper, 79.3 × 56 cm

Ownership stamp of Peter Leopold, grand duke of Tuscany; inventory record: ‘32. Plan de la ville d’Osacca et du Palais de l’Empereur’.

Osaka castle (Osaka‑jo¯ ) was one of the most important places in Japan during the Azuchi-Momoyama period. It was during this era that the unification of Japan took place, starting in 1573 when the daimyo¯ Oda Nobunaga deposed the last shogun from the Ashikaga clan, and ending in 1615 when Osaka castle was conquered by the troops under the command of the Tokugawa.

Oda Nobunaga and his successors, namely Toyotomi Hideyoshi, Tokugawa Ieyasu and the descendants of the latter, flaunted their power by commissioning the construction of castles of prodigious size and splendour. The biggest and most magnificent included the castles in Himeji (near Kobe), Osaka and Edo, present-day Tokyo.

The grandiose Osaka‑jo¯ , begun in 1583 and completed in around 1586 upon the orders of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, was considered to be unassailable because of its huge double bastions

and ditches. Toyotomi also ordered the creation of the gardens and a yamazato (mountain villa). The interiors were decorated by the school of Kano¯ Eitoku, the most prestigious of the Momoyama period and the early Edo period. After it was conquered and partially destroyed in 1615, the castle was restored under the shogunate of Tokugawa Hidetada in around 1620. It was completely destroyed during bombing raids in the Second World War and rebuilt in 1947. The axonometric drawing from the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, with its highly detailed key labelling fifty-five different features (including the material used to build the roofs of the central tower: stone, lead, copper), is therefore an extraordinary historical document that provides us with a picture of one of the most symbolic places in Japan during the Edo period.

[AC]

Other copies

NA, 4.VELH619-82; Van der Hem, 41:27.

Selected bibliography

Wieder 1925–33, I, pp. 19–20, IV, p. 133, no. 66; Van der Krogt 2005, pp. 401–3; Gosselink 2007, pp. 23, 150, no. 232.

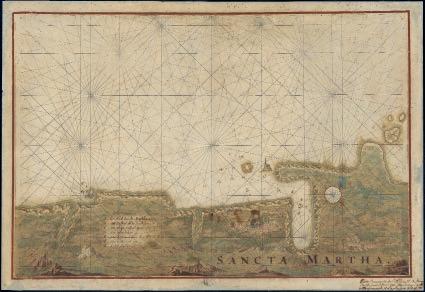

Carte di Castello 10

Sancta Martha

Santa Marta, Colombia

Attributed to Johannes Vingboons and his workshop

Amsterdam, c. 1665–8

Line-and-wash drawing on canvas-backed paper, 76.5 × 52.9 cm

Ownership stamp of Peter Leopold, grand duke of Tuscany; inventory record: ‘73. Carte d’une partie de l’ile et de la ville de Sainte Marthe dans l’Amérique Méridionale. La ville est ruineé, et n’a plus que 30 à 40 […]’.

The coastal city of Santa Marta in present-day Colombia is the country’s oldest colonial city. The territory where the conquistador Rodrigo de Bastidas officially founded Santa Marta in 1525 was discovered back in 1501 by Bastidas himself and Juan de la Cosa, a companion of Columbus, during the first explorations of the southern coast of South America, when there was still some uncertainty about the nature of the lands they had reached. Santa Maria became the starting point for expeditions that led the conquistadores to found Cartagena de Indias, Bogotá and Santa Fe to the south-west, as well as venturing towards the Maracaibo territories and what is now Venezuela, to the

south-east. Violent battles against the native Tairona populations were also organized from Santa Marta for more than a century. The foundation of Cartagena and the concentration of slave traffic from Africa and the native populations in the new city led to the slow decline of Santa Marta, as also highlighted by the inventory note in French. The Carta di Castello, with its very generic key compared to those of the territories and cities under the jurisdiction of the Dutch West India Company, nevertheless reveals the company’s interest in the western territories governed by its rival the Spanish Empire.

Other copies one-off.

Selected bibliography

Wieder 1925–33, IV, p. 131, no. 16; Gosselink 2007, p. 143, no. 56.

Carte di Castello 47

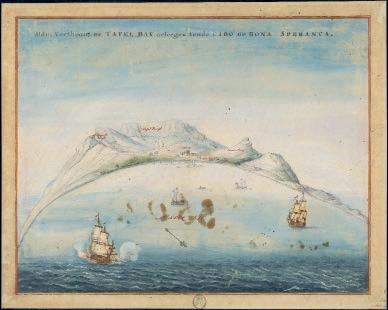

Aldus verthoont de TAFEL BAY

geleegen Aende CABO DE BONA SPERANCA

Table Bay at the Cape of Good Hope Cape Town, South Africa

Attributed to Johannes Vingboons and his workshop

Amsterdam, c. 1655

Line-and-wash drawing on canvas-backed paper, 58.3 × 47 cm

Ownership stamp of Peter Leopold, Grand Duke of Tuscany; inventory record: ‘Monta[…] avec […]’.

The extraordinary marine view of Table Bay, north-west of the Cape of Good Hope, observed from an elevated position out at sea, a few miles offshore, creates the pictorial illusion of an aerial image within which the beauty and airiness of the elements unfurl. The sea, the breeze highlighted by the crests of the waves, the ships driven by the wind and the mountains of the Cape that stand out against the clear blue sky, give the viewer a feel for the sensory experience of sailing. At the same time, Vingboons’s miniaturistic style accurately defines the profile of the mountains and the location of the fort, which are important details for those approaching the bay by sea.

Although Cape Town did not have a particularly sheltered natural harbour, the nearby Cape of Good Hope offered an intermediate landing place that was fundamental for Dutch ships crossing the Atlantic and Indian Oceans on their way to Asia or the Netherlands. This is why Johan Antoniszoon van Riebeeck (1619–77), who had been an officer in the Dutch East India Company since 1639, was tasked with founding a fortified landing place in 1652. Van

Riebeeck built a properly equipped port, a fort and a number of farms for growing vegetables and supplying fresh food over a ten-year period. He made contact with the African Khoekhoe population – given the derogatory name of ‘Hottentots’ by the Dutch, an onomatopoeic term that recalls stutterers due to the phonetics of their language (see CdC 79–82) – and began trading goods produced or imported by the Dutch, particularly bread, pipes, metal objects and alcoholic drinks (CdC 80) for the livestock raised by the Khoekhoe. The colonial city’s efficient organization and its agricultural production system, as well as the presence of a hospital, made it an almost compulsory stopping point for many ships – Dutch or otherwise – circumnavigating Africa. The strategic importance of Table Bay and Cape Town is illustrated by dozens of cartographic documents – primarily to be found in Dutch archives and libraries – showing the fort, the warehouses and the territory. Cape Town remained a Dutch colony until 1795, when it was conquered by the British.

[AC]

Other copies

NA, 4.VELH619-36.

Selected bibliography

Wieder 1925–33, I, p. 14, IV, p. 131, no. 34; Gosselink 2007, pp. 19, 148, no. 165; Atlas of Mutual Heritage, s.v.