Rome between Lights and Shadows

Reconsidering “Renaissances” and “Decadence” in Early Medieval Rome

Ivan Foletti & Sabina Rosenbergová

Introduction: between “renaissance” and “decadence”

The art historical idea of medieval “renaissances”, as so famously expounded by Erwin Panofsky, refers to moments when interest in antique visual patterns – Greek, Roman, and Late Antique – is renewed1. The basic framework for this idea was Panofsky’s, but it has also been developed by many scholars troughout the second half of the twentieth century. The renewed interest in antique visual patterns is often, in this telling, accompanied by the use of antique iconographic patterns 2. In opposition to these moments there were, in keeping with the Vasarian tradition, periods of relative ignorance of the antique heritage and visual language. These have been considered dark periods of cultural decline 3

This well-known narrative of the rise and decline, applied also to the art in Rome, told through the entire nineteenth century and a good part of the twentieth by scholars like Giovanni Battista De Rossi, Orazio Marucchi, Franz Xaver Kraus,

1 Erwin Panofsky, “Renaissance and Renascences”, The Kenyon Review, vi/2 (1944), pp. 201–236; Kurt Weitzmann, The Joshua Roll: a Work of the Macedonian Renaissance, Princeton, nj 1948.

2 On the various medieval renaissances see, e.g., Renaissances Before the Renaissance. Cultural Revivals of Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, Warren Treadgold ed., Standford 1984; La Renaissance? Des Renaissances? (viiie–xvie siècles), MarieSophie Masse ed., Paris 2010.

3 On this question see the general and splendid reflection by Angiola Maria Romanini, “Il concetto di classico e Alto Medioevo”, in Magistra Barbaritas. I barbari in Italia, Maria Giovanna Arcamone ed., Milan 1984, pp. 665– 678.

Joseph Wilpert, and Max Dvořák (to mention only the most famous), sounds obsolete today, and one would think that it was long ago overcome. Nevertheless, the impact of this narrative on perceptions of the art of early medieval Rome has never been systematically analysed, and a closer look reveals its subtle presence in the work of many scholars to this day. Indeed, when one looks at the art of Rome in the ninth and tenth centuries, one finds that a framework of alternating “renaissance” and “decadence” is still predominant. We think this can even be seen, for example, in how much attention scholars have paid to the two centuries in question. The turn of the eighth and ninth centuries has been studied extensively, whereas little work has been done on the tenth century. This state of things has not gone completely unchallenged. Several historians and archaeologists have drawn attention to methodological and historiographical issues in work done on those centuries, and art historians have started, in general, to question the idea of the Carolingian “renovatio”4. With regard to raw material culture, it has been observed that the tenth century saw no decline in population or in the number of buildings commissioned5. An art historical conference with an interdisciplinary approach, dedicated to tenth-century Rome, will take place in the coming months (Conference Roma x secolo, planned for 2021). However, despite these improvements, we believe that scholars in this field still tend to implicitly structure their analyses according to how antique visual patterns were treated at a given moment in time.

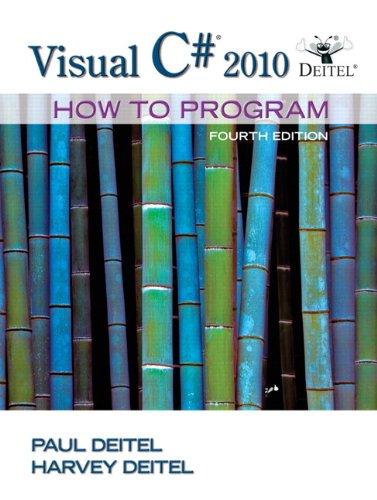

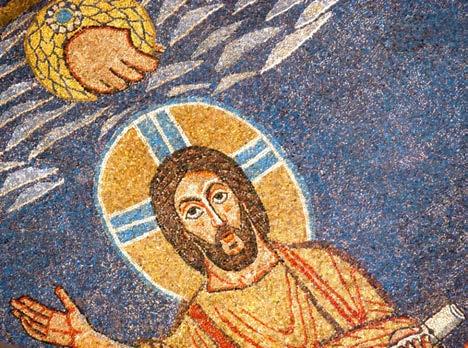

This is problematic if we consider Roman works of the ninth and tenth centuries from the point of view of form and iconography. If, for example, we compare the mosaic decoration of the church of Santa Prassede (commissioned by Paschal i in 817) with the frescoes in the church of Santa Maria in Pallara (late tenth-century decoration in a small church on the Palatine) we will see that, despite the different media, the drawing and plasticity of the bodies are extremely similar, and that there is little attempt at mimesis in either [Figs 1–2]6. The compositions are similar as well: the two apses are dominated by a standing Christ with a raised right arm [Figs 3 – 4]. We do not intend to claim that they are formally identical, but it

would be hard to say, based on their appearance alone, which one of these two apsidal decorations is more reliant on antique models. The composition is a standard one in the Roman visual tradition from late Antiquity to the end of the Middle Ages 7. All evidence thus indicates that the goal of both these compositions was to recall a specific kind of “Antiquity” – the early Christian one. But if we peruse the scholarship done on these two works over the decades, especially that done near the end of the twentieth century, we find claims that Santa Prassede is a product of the “Carolingian renovatio”, while Santa Maria in Pallara is emblematic of the dark and obscure tenth century 8

The difference in the way these two periods are treated also shows up in the number of monuments credited to them. A long list of buildings, mosaics, frescoes, and liturgical objects has been attributed to ninth-century Roman workshops 9. Few works are assigned to the tenth century, even though construction activity did not diminish markedly between those two centuries 10. The supposed decline in artistic production is usually attributed to an unstable political situation caused by Roman aristocrats challenging papal power 11. A (supposed) dearth of monuments and a different political situation have been enough for scholars to consider the tenth century a period of decline after the renewal of the previous century.

As mentioned above, this discrepancy has begun to attract some deserved scholarly attention. Nonetheless, no systematic survey of the relevant scholarship has ever been undertaken 12 For that reason, in this paper we would like to discuss three historiographical narratives which, we think, have led to the ninth century in Rome being viewed as a time of cultural renewal, but the tenth as a dark period of cultural decline.

On the contrary, we will therefore not discuss here another fundamental narrative for the Early Medieval period, the one of the “perennial hellenism” conceived by Ernst Kitzinger in order to describe “survivals” of antique models all through the period. While fundamental, this narrative will become dominant only in the second half of twentieth century, entering the historiography as one of the possible alternative to the paradigms

we will describe here13. Our main goal is to reopen debate which is touching key questions of the framework of medieval art history (in Rome). Let us begin by discussing the twentieth-century idea that there were “renaissances” before the “great Renaissance”, to use the terminology proposed by Panofsky, which contributed to conserving the heritage of Antiquity until our own times. Then we will examine the traditional narrative of the history of Rome and its Early Modern roots. Our aim is to demonstrate the existence of a pattern of rise and fall in the fortunes of the city in accordance with the changing political situation of the popes. Then, finally, there will be a brief discussion of the patterns of historical reflection.

The Carolingian Renaissance and other renaissances: the birth of a mythology

The term “Carolingian Renaissance” was coined in 1839 by Jean-Jacques Ampère (1800 –1864), a French philologist 14. This concept was adopted, with some reservation, by Erna Patzelt and other historians 15. As noted above, this idea was situated within a much wider framework, at the heart of the modern discipline of art history, by Erwin Panofsky in the 1930s 16. The following decade saw the appearance of studies by Hans Swarzenski (1940) and Richard Krautheimer (1942) with a focus on the “Carolingian” period17. While Swarzenski

4 Valentino Pace, “La ‘Felix culpa’ di Richard Krautheimer: Roma, Santa Prassede, e la ‘Rinascenza carolingia’“, in Ecclesiae Urbis, Federico Guidobaldi, Alessandra G. Guidobaldi eds, Vatican City 2002, vol. ii, pp. 65–72; Michel Sot, “Renovatio, renaissance et réforme à l’époque carolingienne: recherche sur les mots”, Bulletin de la Société nationale des Antiquaires de France, (2007), pp. 62–72; Ivan Foletti, Valentine Giesser, “Il ix secolo: da Pasquale i (817– 824) a Stefano v (885– 891)”, in La committenza artistica dei Papi a Roma nel Medioevo, Mario D’Onofrio ed., Rome 2017, pp. 219–238; Giulia Bordi, Carles Mancho, Valeria Valentini, “Dipingere a Roma al tempo di Pasquale i: S. Prassede all’Esquilino e S. Cecilia in Trastevere”, svmma, ix (2017), pp. 64–101.

5 See, for instance, Robert Coates-Stephens, “Dark Age Architecture in Rome”, Papers of the British School at Rome, lxv (1997), pp. 177–232; Roberto Meneghini, Ricardo Santangeli Valenzani, Roma nell’altomedioevo, Rome 2004; Chris Wickham, Medieval Rome. Stability and Crisis of a City, 900 –1150, Oxford 2015. An in-progress thesis by Sabina Rosenbergová is also devoted to these topics.

6 For the state of the art on Santa Prassede see Martin F. Lešák, “Holy Monday at Santa Prassede: Stational Liturgy and Paschal i’s Mosaic Decoration”, in Step by Step Towards the

Sacred. Ritual, Movement, and Visual Culture in the Middle Ages, Martin F. Lešák, Sabina Rosenbergová, Veronika Tvrzníková eds, Brno/Rome 2020, pp. 79–103. See also contributions by Ballardini/Caperna and Bordi/Mancho in this volume.

7 For this iconography see Ivan Foletti, Irene Quadri, “Roma, l’Oriente e il mito della Traditio legis”, Opuscula historiae artium. Supplementum lxii (2013), pp. 16 –37.

8 Among many, see the most influential works by Guglielmo Matthiae, Pittura Romana del medioevo, secoli iv–x, vol. i, aggiornamento scientifico di Maria Andaloro, Rome 1987, pp. 158, 196, 202–203; Richard Krautheimer, Rome, Profile of a City, New Jersey 1980, pp. 109–160.

9 From this long list we can call attention to the recent synthesis of Caroline J. Goodson, The Rome of Pope Paschal i: Papal Power, Urban Renovation, Church Rebuilding and Relic Translation, 817– 824, Cambridge 2010; the research of Erik Thunø (Erik Thunø, Image and Relic: Mediating the Sacred in Early Medieval Rome, Rome 2002; idem, “Materializing the Invisible in Early Medieval Art: the Mosaic of Santa Maria in Domnica in Rome”, in Seeing the Invisible in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages, Giselle de Nie ed., Turnhout 2005, pp. 265–289; idem, The Apse Mosaic in Early Medieval Rome: Time, Network, and Repetition, New York 2015) or the one of the group of scholars centered around the University of Roma Tre (see for example Carles Mancho, “Pasquale i, Santa Prassede, Roma e Santa Prassede”, Arte Medievale, iv/1 (2010 –2011), pp. 31–48; Bordi/Mancho/Valentini, “Dipingere a Roma” (n. 4), pp. 76 – 85.

10 On architectural commissions see especially Coates-Stephens, “Dark Age Architecture in Rome” (n. 5), pp. 177–232. For an overview of the period’s painting cf. Matthiae, Pittura romana del Medioevo (n. 8).

11 Krautheimer, Rome (n. 8), pp. 143–160.

12 Fernand Braudel, “Histoire et sciences sociales: La longue durée”, Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales, xiii/4 (1958), pp. 725–753.

13 The embryo of the Kitzinger’s reflection can be found already in his first main publication: Ernst Kitzinger, Römische Malerei vom Beginn des 7. bis zur Mitte des 8. Jahrhunderts, Munich 1934. This will be further developed in idem, “Byzantine Art in the Period Between Justinian and Iconoclasm”, in Berichte zum xi Internationalen Byzantinisten-Kongress, Munich 1958, pp. 1–50 and idem, “Hellenistic heritage in Byzantine art”, Dumbarton Oaks papers, xvii (1963), pp. 95–116. This theory will, however, touch its apex only in 1977 with the monographic study idem, Byzantine Art in the Making: Main Lines of Stylistic Development in Mediterranean Art, 3rd–7th Century, Cambridge, ma 1977.

14 Jean-Jacques Ampère, Histoire littéraire de la France avant le xiie siècle, Paris 1839. For his biography see Lucien-Anatole Prévost-Paradol, “Discours de reception”, in Académie de France, Paris 1866, online: http://www.academie-francaise. fr/discours-de-reception-de-lucien-anatole-prevost-paradol, [last accessed: 22.5.2020]. Cf. also Sot, “Renovatio, renaissance et réforme” (n. 4) and Pierre Riché, Die Welt der Karolinger, Stuttgart 1981.

15 Erna Patzelt, Die karolingische Renaissance. Beiträge zur Geschichte der Kultur des frühen Mittelalters, Vienna 1924.

16 See Erwin Panofsky, Fritz Saxl, Classical Mythology in Mediaeval Art, New York 1933, further developed in the above-mentioned work by Panofsky, “Renaissance and Renascences” (n. 1).

17 Hanns Swarzenski, “The Xanten Purple Leaf and the Carolingian Renaissance”, The Art Bulletin, xxii/1 (1940), pp. 7–24; Richard Krautheimer, “Introduction to an Iconography of Mediaeval Architecture”, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, v (1942), pp. 1–33, which can be seen as a methodological frame for the second article by idem, “The Carolingian Revival of Early Christian Architecture”, The Art Bulletin, xxiv/1 (1942), pp. 1–38.

1 / Head of Christ, the detail of the apse of the church Santa Prassede, mosaic, Rome, 817–824

2 / Head of Christ, the detail of the apse of the church Santa Maria in Pallara, fresco, Rome, the 970s–990s

3 / Theophany of Christ, the apse of the church Santa

4 / Theophany of Christ, the apse of the church Santa

the 970s–990s

Prassede, mosaic, Rome, 817–824

Maria in Pallara, fresco, Rome,

concentrated on manuscripts, Krautheimer is key to our discussion because he focused on Rome, outlining at the same time a theoretical framework for the iconography of medieval architecture. Krautheimer later applied this notion to the Carolingian Revival of Early Christian Architecture [Fig. 5] The Carolingian period, he argues, corresponds to a revival of antique cultural and visual patterns in Rome, which means that in that era, the Late Antique Roman Christian tradition was brought back to life in a Christian renaissance 18. Further, Krautheimer suggests that an architectonic structure can, through a reference to another building, bear ideological meaning. The formal elements and spatial relationships of the Early Christian monuments in Rome, he argues in his article The Carolingian Revival, were consciously imitated in some Carolingian churches in the ninth century in order to clearly express an “ideological message” of the renewal of the Church and Empire. Nevertheless, Krautheimer does not see these references as “copying” in the modern sense of the word. Instead, he holds that a building’s layout, proportions, or dedication to certain saints can hold symbolic significance19. He also argues that there were two medieval revivals of the Antique, both orchestrated by the Roman papacy: the Carolingian revival and the papal reformation at the end of the eleventh and beginning of the twelfth centuries 20. Krautheimer suggests that these two medieval renaissances were a bridge between Antiquity and the (Great) Renaissance.

Here it is worth pointing out that Valentino Pace has argued that applying the notion of “renaissances” to Christian Rome is, in and of itself, suspicious. This is because the city, as a Catholic capital presided over by the popes, had always reflexively turned its attention to the past and its own uninterrupted continuity with that past ever since Late Antiquity; moreover, this has always entailed employing a specific visual rhetoric 21 Despite this sage criticism, the narrative framework set forth in Krautheimer’s authoritative studies has continued to influence modern scholars’ views of medieval Rome.

Krautheimer’s ideas raise the question of a potential link to Panofsky’s notion of “medieval renaissances”. Panofsky introduced this theory of

the interpretation of images in 1933 book Classical Mythology in Mediaeval Art and in his 1939 essay Studies in Iconology: Humanistic Themes in the Art of the Renaissance. While we do not have any decisive evidence of a direct interaction, similarity in argumentation and chronological proximity let Catherine Carver McCurrach to suppose that Krautheimer arrived to similar framework to approach architecture in the articles published in 1942 2 2. Shortly afterwards, in 1944, Panofsky’s Renaissance and Renascences was published. The crucial thing about this work is that, like Krautheimer, he considers the ninth- and twelfth-century revivals key to the transmission of the classical culture of Antiquity to the Renaissance. And he adds the following:

“The Carolingian revival, which virtually ended with the death of Charles the Bald in 877, was followed by a period as barren as the seventh century and this was succeeded by a new efflorescence which began, roughly speaking, a hundred years later 23.”

Krautheimer essentially claimed the same for medieval Rome. The political and cultural blossoming of the ninth-century Carolingian renaissance was followed by the dark and decadent tenth century and its weak and dependent popes 24

As is well known, Panofsky and Krautheimer not only shared the interest for “medieval renaissances” but had similar biographies as well. Both were émigrées who left Germany before World War ii, taking refuge in the us, where they had successful academic careers 25. Their interest in renaissances and the survival of the humanistic values of Antiquity was typical for scholars from the circle around Warburg’s institute in Hamburg 26 Many of these scholars left Germany in 1933 and the majority found new homes in the us. Moreover, according to Anthony Heilbut, even though his theories are not accepted unanimously, their lives there were no paradise, and they faced increasing discrimination, especially after the death of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882–1945) 27 Their response was to hold tight to humanistic values, and they continued to prefer topics related to the Renaissance, Humanism, and Neo-Platonism. It seems, thus, that it is in this context that the

idea of oft-recurring renaissances appeared. This became their paradigm of cultural values, related to the lives of German émigrées in the us. These values included the freedom of the individual, the independence of reason (in contrast to religious dogma), and the idea of universal human dignity – something which has been linked with the trauma of World War ii 28. It does not seem far-fetched to see Panofsky’s and Krautheimer’s search for renaissances and renewals of humanistic values

18 Cf. in Krautheimer, Rome (n. 8), chapter five (Renewal and Renaissance: The Carolingian Age), sp. p. 141.

19 Krautheimer, Introduction to an Iconography of Mediaeval Architecture (n. 17), pp. 1–33, sp. pp. 1–20. See also Catherine Carver McCurrach, “‘Renovatio’ Reconsidered: Richard Krautheimer and the Iconography of Architecture”, Gesta, l/1 (2011), pp. 41– 69, sp. pp. 42–49.

20 Krautheimer, “The Carolingian Revival” (n. 17), p. 28.

21 Pace, “La ‘Felix culpa’ di Richard Krautheimer” (n. 11). This idea has been further developed by Ivan Foletti, Irene Quadri, “L’immagine e la sua memoria: l’abside di Sant’Ambrogio a Milano e quella di San Pietro a Roma nel Medioevo”, in Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, lxxvi/4 (2013), pp. 475–492.

22 Erwin Panofsky, Fritz Saxl,“Classical Mythology in Mediaeval Art”, Metropolitan Museum Studies, iv/2 (1933), pp. 228–280; Erwin Panofsky, Studies in Iconology: Humanistic Themes in the Art of the Renaissance, New York 1939. On the argument see: McCurrach, “‘Renovatio’ Reconsidered” (n. 19), pp. 41– 69, sp. p. 49.

23 Panofsky, “Renaissance and Renascences” (n. 1), p. 212. Later developed in idem, Renaissance and Renascences in Western art, Stockholm 1960.

24 Cf. Krautheimer, Rome (n. 8), chapter six (Realities, Ideologies, and Rhetoric), sp. pp. 143–148. It should not be overlooked that Krautheimer never devoted any deeper analysis to the situation of art in Rome in the tenth century, as he honestly states in his Profile, see notes on the page 348.

25 For Krautheimer in general see Golo Mauer, “Richard Krautheimer (1897–1994)”, Klassiker der Kunstgeschichte. Von Panofsky bis Greenberg, Ulrich Pfisterer ed., pp. 90 –106; Charles B. McClendon, “Encounter: Richard Krautheimer”, Gesta, liv/2 (2015), pp. 123–126. Regarding Panofsky, the literature is immense, but we can mention the recent brief contribution by Irving Lavin, focused on the acculturation of the émigré Panofsky to the us. Irving Lavin, “American Panofsky”, in Migrating Histories of Art: Self-Translations of a Discipline, Maria T. Costa, Hans C. Hönes eds, Berlin/Boston 2019, pp. 91–97.

26 Ernst Gombrich, in his article “The Style all’antica. Imitation and Assimilation”, in The Renaissance and Mannerism. Studies in Wester Art, vol ii, Princeton, nj 1963, p. 32, n. 3 mentions the following studies as examples of interest in the nachleben of Antiquity in the Middle Ages: Adolf Goldschmidt, “Das nachleben der Antiken Formen in Mittelalter”, Vorträge der Bibliothek Warburg, (1921/1922), pp. 40 –50; Wilhelm Pinder, “Antike Kampfmotive in neuerer Kunst”, Münchner Jahrbuch der bildenden Kunst, 1928, pp. 353–375; Richard Krautheimer, Lorenzo Ghiberti, Princeton 1956, sp. chapter viii; Horst W. Janson, The Sculpture of Donatello, Princeton 1957, sp. p. 100; Heinz Ladendorf, Antikenstudium und Antikenkopie. Vorarbeiten zu einer Darstellung ihrer Bedeutung in der mittelalterlichen und neueren Zeit, Berlin 1953.

27 Anthony Heilbut, Exiled in Paradise: German Refugee Artists and Intellectuals in America, from the 1930s to the Present, New York 1983.

28 Kevin Parker, “Art History and Exile: Erwin Panofsky and Richard Krautheimer”, in Exiles and Emigrés, The Flight of European Artists from Hitler, Stephanie Barron ed., Los Angeles 1997, pp. 317–325; Karen Michels, Art History, German Jewish Identity, and the Emigration of Iconology, in Jewish Identity in Modern Art History, Catherine M. Soussloff ed., Berkeley 1999, pp. 167–179.

5 / Richard Krautheimer in his office at the Institute of Fine Arts, photography, New York University, the 1960s

as a reaction to the situation of the German refugee intellectuals in the mid-twentieth century. It would, of course, be too reductive to argue that Panofsky’s and Krautheimer’s scholarship was merely a reaction to their personal experiences. Their training, their curiosity, their intellectual environment, and emigration all played a role. On the other hand, we have no doubt that a tragedy of the dimensions of the exile, and of the lost of the homeland, affected them dramatically. Their belief in renaissances of humanistic values appears to be a logical reaction to one of the worst periods of “barbarism” in the history of humankind: the World War ii and its consequences. This was particularly apt in art history, a field built, since the sixteenth century, on the idea that the Renaissance was one of the fundamental events in European cultural history. This idea was promoted especially by Giorgio Vasari (1511–1575), who perceived antique visual patterns as the antithesis of medieval barbarism [Fig. 6] 29. For Vasari, antique art was perfect, but then:

“it came to pass that almost all of the barbarian nations in various parts of the world rose up against the Romans, and, as a result, not only did they bring down so great an empire in a brief time but they ruined everything, especially in Rome itself. With Rome’s fall the most excellent craftsmen, sculptors, painters, and architects were likewise destroyed […] 30.”

This artistic disaster lasted until 1240 and the birth of the Florentine Cimabue, who then taught Giotto, who was an excellent imitator of nature. Those two facilitated the rebirth of antique art, whose origin was nature itself 31. This general framework was later applied to the entire emerging field of art history by Jean-Baptiste Seroux d’Agincourt (1730–1814) who in his Histoire de l’Art par les Monumens, depuis sa décadence au iv e siècle jusqu’à son renouvellement au xvi e siècle, accepted Vasari’s views of the Middle Ages 32

Thus if Panofsky and Krautheimer were, at least in part, projecting into their research their experience of the first half of the twentieth century, they were also following a continuous and deeply embedded art historical pattern. Vasari’s view of the Middle Ages had, of course, been challenged as early as the beginning of the twentieth century by scholars such as Alois Riegl and Franz

6 / Cristoforo Coriolano, portrait of Giorgio Vasari, Illustration from Le Vite by Giorgio Vasari, 1568

7 / Fratelli D’Alessandri, photograph of Ferdinand Gregorovius, Rome

Wickhoff 33. But as Maria Angiola Romanini has shown, the tendency to treat the Middle Ages as a vehicle for the transmission of Antiquity was still alive in the 1960s, for instance in the works of Otto Pächt. According to him, “the Dark Ages appear illuminated by the windows through which they have seen the light of the Classical legacy”34 These authors essentially judged the Middle Ages on their success (or lack thereof) in conserving the Classical heritage, assuming a framework of positive periods of Classical revival and dark periods that would then neglect this legacy.

In addition to resulting in a generally negative appraisal of medieval art, this approach encourages one to see a repeating pattern of “dark ages” followed by “renaissances” (or vice versa) wherever one looks. This regular historical mechanism can then help one to understand not only the past, but also the present. Panofsky and Krautheimer could hope for a better world to come, and at the same time see iterations of this cycle in the Middle Ages. If we are correct in seeing this as a crucial aspect of their thought, it does not necessarily lessen the value of their work, but it reminds us to be very aware of the general framework that they and subsequent scholars have applied.

A Romano-centric approach: the papal narrative

A second historiographical phenomenon that we would like to point out concerns Early Medieval Rome in particular. Rome had been, until its secularization, governed for many centuries by an uninterrupted line of pontiffs. It had been the center of the Roman Catholic Church, and their authority was derived from the continuity of papal power. Therefore, the prevailing habit was always to narrate the history of the city in terms of the papacy 35. This tendency was strongest, of course, for Roman Catholic historians, with the tradition being established as early as the sixteenth century. The founder of modern sourcebased history, Leopold von Ranke (1795–1886), emphasized the importance of liberating the history of the papacy as an institution, and of the city of Rome itself, from the history of religion and the Reformation 36. But, as has been argued

by Wickham, this problem has not disappeared from modern historiography 37

Despite his confessional background, the pivotal role of the pontiffs is firmly embedded in the work of the Protestant Ferdinand Gregorovius (1821–1891). His History of the City of Rome in the Middle Ages [F ig. 7], published between 1859 –1872, is one of the most traditional histories of medieval Rome, and had great influence on the work of Richard Krautheimer and Paolo Brezzi 3 8

29 See the excellent synthesis by Barbara Forti, “Vasari e la ‘ruina estrema’ del Medioevo: genesi e sviluppi di un’idea”, Arte medievale, iv/4 (2014), pp. 231–252.

30 Giorgio Vasari, The Lives of the Artists, trans. Julia Conaway Bondanella, Peter Bondanella, Oxford 1998, p. 4.

31 Ibidem, pp. 7–36.

32 Jean-Baptiste Seroux d’Agincourt, Histoire de l’Art par les Monumens, depuis sa décadence au ive siècle jusqu’à son renouvellement au xvie, Paris 1810 –1823. For the figure of Seroux d’Agincourt see the excellent monograph by Daniela Mondini, Mittelalter im Bild: Séroux d’Agincourt und die Kunsthistoriographie um 1800, Zürich 2005. For the general context see the collective monograph Séroux d’Agincourt e la storia dell’arte intorno al 1800, Daniela Mondini ed., Rome 2019.

33 Alois Riegl, Spätrömische Kunstindustrie, Vienna 1901; Franz Wickhoff, Die Wiener Genesis, Vienna 1903. There is abundant bibliography about the Vienna School of Art History. For the construction of the Middle Ages we wish, however, to refer the reader to the excellent and synthetic contribution of Jaś Elsner, “The Viennese Invention of Late Antiquity: Between Politics and Religion in the Forms of Late Roman Art”, in Empires of Faith in Late Antiquity. Histories of Art and Religion from India to Ireland, Jaś Elsner ed., Cambridge 2020, pp. 110 –127.

34 Otto Pächt, The Pre-carolingian Roots of Early Romanesque Art, in Studies in Western Art, Princeton 1963, p. 67. Cf. Romanini, “Il concetto di classico e Alto Medioevo” (n. 3).

35 We derive our argument on this matter mainly from the synthesis by Wickham, Medieval Rome (n. 5), sp. pp. 1–5, 13–20.

36 On Leopold von Ranke and his method see Georg G. Iggers, James M. Powell, Leopold von Ranke and the Shaping of the Historical Discipline, Syracuse 1990. For his attempt to compose a general history of the papacy as institution outside the frame of the history of religion see Leopold von Ranke, Die römischen Päpste, ihre Kirche und ihr Staat im sechzehnten und siebzehnten Jahrhundert, Berlin 1834–1836. For a slightly later attempt to compose the history of Rome as a city see Alfred von Reumont, Geschichte der Stadt Rom, 3 vols, Berlin 1867–1870 and Ferdinand Gregorovius’ more famous Geschichte der Stadt Rom im Mittelalter, published between 1859–1872; for an English translation see Ferdinand Gregorovius, History of the City of Rome in the Middle Ages, Cambridge 2010. On Von Reumont and Gregorovius see Alberto Forni, “Ferdinand Gregorovius storico di Roma medievale”, in Roma medievale. Aggiornamenti, Paolo Delogu ed., Florence 1998, pp. 13–24, and on Gregorovius see also Maya Maskarinec, “Ferdinand Gregorovius versus Theodor Mommsen on the City of Rome and Its Legends”, Journal of the History of Humanities, i/1 (2016), pp. 101–128.

37 Wickham, Medieval Rome (n. 5), pp. 1–5, 13.

38 For Krautheimer’s dependence on Gregorovius, mainly for the tenth century, see Krautheimer, Rome (n. 8), note on p. 348. For Brezzi see Wickham, Medieval Rome (n. 5), pp. 1, 13.

8 / The title page of so-called Magdeburg Centuries, Basel 1559

9 / Étienne-Jehandier Desrochers, Portrait of Caesar Baronius, engraving, 17th century

Gregorovius presents the history of the studied period in a very traditional way: the ninth century is depicted as a glorious time of strong and powerful popes and their great artistic commissions 39 The first half of the tenth century, on the other hand, is a decadent period of weak, ineffectual popes controlled by aristocrats, and – even worse – by vicious aristocratic women! The popes were assassinated, executed, or had mistresses until the situation was briefly improved by the Ottonian emperors 4 0. Gregorovius focuses on the struggle for power between the popes (supported by the emperors) and the local nobles; in the years after 1000, the struggle was between popes and emperors. This perspective is present, naturally, in the work of Catholic historians as well. They welcome the end of the dreadful tenth century and the arrival of the Gregorian reform movement in the second half of the eleventh century, when Leo ix, Gregory vii, and their successors re-established a powerful papacy, albeit one in conflict with the Holy Roman emperors and the Byzantines 41. The fourteenth century, when Rome again fell into chaos because the papacy had been “captured” and taken to Avignon, is treated similarly 42. Despite some variation in terminology, this alternation of glory and decadence is one of the leitmotivs of most narrative histories of medieval Rome. Whether a period was glorious or decadent will depend on whether the pope at the time was strong or weak, or whether he was even present in the city. To put it simply, the history of the city mirrored the political fortunes of the papacy. This is what Chris Wickham has fittingly called the “papal narrative”43

We would like to argue that this pattern originated in, and was codified during, the Reformation and Counter-Reformation. Very early on, Lutherans felt a need to write a history of the Church from their own standpoint 44, and this need manifested itself in the Magdeburg Centuries, compiled by the theologian Matthias Flacius (1520–1572)4 5. This work – published in seven volumes in Basel between 1559 and 1574 – deals with the “Church of Christ” century by century. Its full title makes clear its topics: the Church’s propagation, persecution, tranquility, doctrine,

heresies, ceremonies, governance, schisms, synods, personalities, miracles, testimonies, religious lives outside the Church, and the political status of the Empire [Fig. 8]46. It treats the history of the Church from its beginnings to the thirteenth century, and was designed to show how Lutheran doctrine emerged from the chaos that enveloped the medieval Church. The papacy is pictured as being in gradual decline. From the seventh century on, the pontiffs were no longer guardians of the true Church but rather Antichrists. Other German proto-historians, departing from the narrative frame of the Magdeburg Centuries, loved to call tenth-century Rome a “pornocracy”47. The Magdeburg Centuries and these other works had great influence within Protestant circles 48

There was, predictably, a reaction from the Catholics. A history of the first twelve centuries of the Church, sponsored by the papacy, was composed by Cardinal Caesar Baronius (1538 –1607)49. These Annales Ecclesiastici reflected the official position of the Catholic Church after the Council of Trent (ended 1563) and aimed to codify the history and doctrine of the Catholic Church according to new principles formulated by the Council50. Baronius defended the papacy against the Protestants’ attacks, and denied that it was an institution in continuous decline [Fig. 9]

39 Ferdinand Gregorovius, History of the City of Rome in the Middle Ages, vol. iii, London 1895, pp. 1–205.

40 Ibidem, pp. 216 –317. Cf. also Ferdinand Gregorovius, “L’impero, Roma e la Germania. A proposito dal Sacro Romano Impero di James Bryce”, in Passeggiate per l’Italia, Rome 1907, pp. 330, 404, 498. On the Ottonians see mainly Gregorovius, History of the City (n. 39), vol. iii, pp. 494–495.

41 See especially Augustin Fliche, La Réforme grégorienne, 3 vols, Louvain/Paris 1924–1937, but also the much later work by Herbert E. J. Cowdrey, Pope Gregory vii, 1073–1085, Oxford 1998. See also Wickham (n. 5), p. 14, n. 28.

42 An eloquent example might be the work of Catholic historian August Franzen, Kleine Kirchengeshichte, Freiburg im Breisgau 1970, pp. 220–226.

43 Wickham, Medieval Rome (n. 5).

44 Eduard Fueter, Geschichte der neueren Historiographie, Munich/ Berlin 1936, p. 246.

45 Wilhelm Preger, Matthias Flacius Illyricus und seine Zeit, Hildesheim 1861; Gustav Kawerau, “Matthias Flacius”, in Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, Samuel MacAuley Jackson ed., London 1909, vol. iv, pp. 321–323; Jörg Bauer, Matthias Flacius Illyricus, 1575–1975, Regensburg 1975; Oliver K. Olson, Matthias Flacius and the Survival of Luther’s Reform, Minneapolis 2011.

46 Matthias Flacius et al., Ecclesiastica historia integram ecclesiae Christi ideam, quantum ad locum, propagationem, persecutionem, tranquillitatem, doctrinam, haereses, ceremonias, gubernationem, schismata, synodos, personas, miracula, martyria, religiones extra

ecclesiam, et statum imperii politicum attinet, secundum singulas centurias, perspicuo ordine complectens : singulari diligentia et fide ex vetustissimis et optimis historicis, patribus, et aliis scriptoribus congesta per aliquot studiosos et pios viros in urbe Magdeburgica, 7 vols, Basel 1559–1574.

47 Valentin E. Löscher, Historie des römischen Huren-Regiments der Theodore und Maroziae: in welcher Die Begebenheiten des zehenden Seculi und Intriguen des Römischen Stuhls ausgeführet werden, nebst einer längst verlangten Einleitung Zur Histor. Medii Aevi, verschiedenen neuen Geographischen und Genealogischen Tabellen, und einer Anzahl Historischer Beiweißthümer wieder das Pabstthum, Leipzig 1705. The book was published again after 20 years, this time without the reference to pornocracy. Valentin E. Löscher, Historie der mittleren Zeiten, als ein Licht aus der Finsternis, Leipzig 1725.

48 Euan Cameron, “Primitivism, Patristics, and Polemic in Protestant Vision of Early Christianity”, in Sacred History. Use of the Christian Part in the Renaissance World, Katherine Van Liere, Simon Ditchfield, Howard Louthan eds, Oxford 2012, pp. 27–51, sp. pp. 47–52; Irena Backus, Medieval History and the Catalogus testium veritatis of Mathias Flacius Illyricus, revised by Simon Goulart, a talk at the 2011 Kalamazoo Congress for Medieval Studies. Accessible at: https:// www.academia.edu/1690312/Medieval_history_and_the_ Catalogus_testium_veritatis_of_Mathias_Flacius_Illyricus_ revised_by_Simon_Goulart [last accessed: 15.2.2020].

49 The bibliography on Cesare Baronius as historian is enormous. Consult, for example Cesare Baronio tra santità e scrittura storica, Giuseppe A. Guazzelli ed., Rome 2012; Baronio e le sue fonti, atti del convegno internazionale di studi, (Sora, 10 –13 ottobre 2007), Luigi Gulia ed., Sora 2009.

50 Simon Ditchfield, Liturgy, Sanctity and History in Tridentine Italy, Cambridge 1995.

Instead, he posited that the Church had always been the same (sempre eadem) since its apostolic days 51. But Baronius did adopt the methodological framework of the Magdeburg Centuries in the sense that he, too, divided the history of the Church into centuries 52. And what of the ninth and tenth centuries? Baronius calls the ninth splendid and the tenth decadent 53. In his interpretation, after the Carolingian empire collapsed, Europe was plunged into chaos and the papacy lost control of the city to the aristocrats. At the beginning of his chapter about the tenth century, he claims that with the year 900, a “dark century” (saeculum obscurum) began, during which “Christ was in deep slumber”5 4. In Baronius’ narrative, papal power and initiative are clearly the main criterion for judging a period. Popes who had great power (whether real or only in the eyes of Baronius) were worthy of praise. These strong figures illuminated, by their splendor, the whole glorious period of their reign. This point of view is clearly a consequence of the Counter-Reformation and the idea that the papacy should be strong, powerful, and universal. Such a perspective has survived in Catholic historiography with figures such as Hartmann Grisar (1845–1932) and, especially, Louis Duchesne (1843–1922) 55

Historians’ perception of the ninth and tenth centuries, then, was very much tied to papal politics. What is more curious, however, is that these projections and the resulting judgements were perpetuated, for various reasons, all the way from the sixteenth century to the twentieth.

Historic recurrence as a general paradigm of historical reflection

The idea of cycles, with moments of decay followed by rebirth or renaissance, has been present in historical thought at least since Plato’s Republic and Polybius’ Historiae 56 In more recent times, an extreme version of this notion appeared in Nietzsche’s Doctrine of Eternal Recurrence 57 This is not the place to discuss this fundamental philosophical issue, but we think it worth mentioning that in the 1960s, Gilles Deleuze (1925–1995), in his book on Nietzsche’s philosophy, interprets the recurrence as a force “endowed with centrifugal

powers that drive away the entire negative […] The eternal return is the Repetition, but the Repetition that selects, the Repetition that saves”58 In emphasizing the positive aspects of these recurrences (an emphasis which is not present in Nietzsche’s book), Deleuze may have been coping with the turbulent Europe of the mid-twentieth century, an aspect he experienced personally in loosing his brother during the transport to Buchenwald59. For a French philosopher working in the years after World War ii, there were pressing questions of European identity, the crisis of the colonial system, and the Cold War. Did this reality encourage Deleuze to find hope for the future in a cyclical pattern.

Not being anthropologists nor philosophers, we will cut these reflections short here. We would like to highlight, however, the necessity that we have as humans and historians – a necessity present through the centuries – of constructing a predictable pattern for understanding history. Mircea Eliade would describe it as the wish to find a transhistorical justification for historical events 60. This wish even shows up in popular wisdom, which tells us that “history repeats itself”. This trope is obviously not true, and history is, definitely, always different. And if certain patterns seem to repeat themselves, this is because understanding them as iterations of a cycle fulfils our psychological need to control and predict the future.

If history is always different, what does remain constant, perhaps, is the way scholars reproduce intellectual patterns. According to Sigmund Freud and later exponents of psychoanalysis, this mechanism comes from our need to face and overcome the fear of the unknown 61. Believing that history repeats itself is a way of facing the horror of a future where everything is unknown except for the fact that we will die. We are further encouraged in this tendency by the comforting effect that repetition has on our minds 62

Now, returning to the real focus of this paper, what of the traditional judgements of the ninth and tenth centuries in Rome? Were those centuries really so different, or have they been forced into a typical (or even archetypical) pattern of rebirth and decay?

Conclusion: missing material culture?

In the preceding pages we have touched on two crucial historical periods which have had outsized impact on the historiography of Rome – the World War ii and the Counter-Reformation. We have also looked at how a cyclical reading of Rome’s history seems to belong to a much larger framework reappearing across many centuries and rooted in the nature of the human mind. Together, these two factors can help us to better understand why the various histories of Rome has typically exhibited some shared characteristics. At the same time, they can explain some of the general tendencies of art history when it turns to the “Middle Ages”.

These two factors, obviously, have not been the only ones that have determined our perceptions of the ninth and tenth centuries in Rome. A more objective factor, so to speak, which seems to have supported those conclusions is the almost complete absence of monuments from the tenth century, whereas a great number of monuments have survived from, or have been ascribed to, the ninth century 63

But after what we have said about the tendency to perceive history cyclically, is this difference real? One of the problems is that many Roman monuments, especially paintings, belonging to the period between the ninth and eleventh centuries, have been dated solely on the base of formal analysis. The preconception we have just described, i.e. that the tenth century was a time of decay, may have led scholars to ascribe high-quality tenth-century works to either the ninth or the eleventh centuries 64

Further doubts have been raised through research undertaken by Robert Coates-Stephens 65 In the late 1990s, he published an article on the commissioning of churches during the so-called “dark centuries” (i.e. the seventh and the tenth). The list shows, surprisingly, that the number of churches commissioned is comparable across

52 Ibidem, “Cesare Baronio and the Roman Catholic” (n. 51), pp. 58– 63; Stefano Zen, Baronio storico: controriforma e crisi del metodo umanistico, Naples 1994.

53 Cesar Baronius, Annales Ecclesiastici, vol. xv, Lucca 1783, p. 500.

54 “Dormiebat tunc plane alto (ut apparet) sopore Christus, cum navis fluctibus operiretur: Et quod deterius videbatur, de erant qui Dominum sic dormientem clamoribus excitarent discipuli, stertentibus omnibus”. Ibidem, pp. 566 –578, for the saecolum obscurum see p. 500. See also Girolamo Arnaldi, “Mito e realtà del secolo x romano e papale”, in Settimane di studio del Centro Italiano di Studi sull’Alto Medioevo, xxxviii/1 (1990), pp. 25–56.

55 See, in general, Rosamond McKitterick, Rome and the Invention of the Papacy: The Liber Pontificalis, Cambridge 2020.

56 Plato, Republic, Christopher J. Emlyn-Jones, William Preddy eds, Cambridge, ma 2013; Polybius, Historiae, Ludwig Dindorf ed., Munich/Leipzig 2001. Garry W. Trompf, The Idea of Historical Recurrence in Western Thought. From Antiquity to the Reformation, Berkeley / Los Angeles / London 1979, pp. 4–115.

57 Martin Heidegger, Nietzsche, The Eternal Recurrence of the Same, San Francisco 1991; Karl Löwith, Nietzsche’s Philosophy of the Eternal Recurrence of the Same, Berkeley 1997.

58 Deleuze, Nietzsche et la philosophie, Paris 1962, p. 66 quoted in Paolo D’Iorio, The Eternal Return: Genesis and Interpretation, 2011, p. 4, published online: http://www.nietzschecircle.com/ Pdf/Diorio_Chouraqui-FINAL_APRIL_2011.pdf [23.5.2020].

59 François Dosse, Gilles Deleuze, Felix Guattari, biographie croisée, Paris 2007.

60 Mircea Eliade, The Myth of the Eternal Return, Princeton 1965, p. 147.

61 Sigmund Freud, “Remémoration, répétition, perlaboration (1914)”, in La technique analytique, Paris 1953, pp. 103–115. See also André Quaderi, “Mémoire et souvenir dans la clinique du dement”, Psychothérapies, xxvii/4 (2007), pp. 213–219.

62 We refer here to a paper by Zuzana Frantová "Liminality, Embodiement and Iconic Presence. Serial Images in French Pilgrimage Churches", conference Walking and Iconic Presence, 27. – 28. listopad 2017, Brno 2017.

63 See the lists of Matthiae, Pittura Romana del medioevo (n. 8), pp. 263–298; Krautheimer, Rome (n. 8), pp. 109–160.

51 On this concept see, for instance, Giuseppe A. Guazzelli, “Cesare Baronio and the Roman Catholic Vision of the Early Church”, in Sacred History. Uses of the Christian Past in the Renaissance World, Katherine Van Liere, Simon Ditchfield, Howard Louthan eds, Oxford 2012, pp. 52–71, sp. pp. 54– 60.

64 For an interesting example, take the fact that since the 1970s, a significant number of pictorial mural decorations – among them many murals that had been regarded as having been produced in the tenth century – have been re-ascribed to the period of the so-called Gregorian reform. That occurred after new theories about the art of the Gregorian reform were published primarily by Otto Demus, Helène Toubert and Ernst Kitzinger (Hélène Toubert, “Le renouveau paleochrétien à Rome au début du xiie siécle”, Cahiers Archéologiques, xx [1970], pp. 99–154; Otto Demus, Romanesque Mural Painting, New York 1970; Ernst Kitzinger, “The Gregorian Reform and the Visual Arts: A Problem of Method”, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, xxii [1972], pp. 87–102.) For some examples in Rome, see an updated version of the corpus of paintings by Guglielmo Matthiae (published in 1987), especially the commentary by Maria Andaloro on the tenth century. See also, for instance, the case of the church of Sant’Andrea al Celio: Carlo Bertelli, “La pittura medievale a Roma e nel Lazio”, in La pittura in Italia. L’Altomedioevo, Milano 1994, p. 226; Serena Romano, “Il Cristo e Archangeli nell’Oratorio di Sant’Andrea al Celio”, in Riforma e Tradizione, Rome 2006, pp. 60 – 62; Alessandra Acconci, “L’Oratorio di Sant’Andrea al Celio: alcune note sul dipinto medievale nel sottotetto”, Römisches Jahrbuch der Bibliotheca Hertziana, xlii (2015/2016), pp. 35– 68.

65 Robert Coates-Stephens, “Dark Age Architecture in Rome” (n. 5), pp. 177–232.

all of the centuries considered. What differs greatly, however, are the numbers of surviving churches. From the period of the so-called “Carolingian renaissance”, from 12 to 18 churches are known to have survived. Only three churches have survived, however, from each of the seventh and tenth centuries.

The explanation for this might seem simple. The churches of the tenth century could have been small buildings which were later demolished or rebuilt, or even just fell apart because they were poorly built. This seems like a reasonable conclusion considering the surviving single-nave tenth-century structures – e.g. the churches of Santa Maria in Pallara and San Tommaso in Formis. The churches from the ninth century, by contrast, are impressive, monumental structures decorated with mosaics, one of the longest-lasting media available.

But the sources tell us, for instance, about a church paid for by Emperor Otto iii, San Bartolomeo all’Isola (originally dedicated to Saints Adalbert and Paulinus), from which it seems that only the crypt has survived 66. We have also lost buildings paid for by wealthy aristocratic families in the tenth century, such as Alberich’s residence, the newly founded monastery of St Cyriakus close to Santa Maria in Via Lata (which was founded by Alberich’s female relatives) 67. The decision to preserve or demolish a monument is often influenced by more than purely practical considerations, and it may be that the classic Roman Catholic narrative of Roman history, centered on

the popes, encouraged the preservation of monuments associated with the popes and allowed the destruction of those not.

We would like to conclude with the following thought: the history (and consequently the art history) of the ninth and tenth centuries in Rome, as we know them, have largely been constructed under the influence of a historiographical tendency that was influenced to an exceptional degree by the Reformation and Counter-Reformation in the sixteenth century, and the turmoil of the mid-twentieth century. These tendences have encouraged scholars to see, in Roman history, a repeating pattern of contrasting positive and negative episodes. In our times, these episodes are usually no longer called “renaissances” and “decadence”, but the pattern remains 68. We think it urgent that scholars reconsider the material culture of this period without allowing that pattern to unduly influence their work.

66 For the foundation of the church by Otto iii and translation of the relics see mgh, ss 4, 575–576, n. 21. See also S. Bartolomeo all’Isola: storia e restauro, Maria Richiello ed., Rome 2001.

67 Alberich (ca 912–954) was de facto ruler of Rome beginning in 932 until his death. On the foundation of the monastery see especially Riccardo Santangeli Valenzani, “Topografia del potere a Roma nel x secolo”, in Three Empires, Three Cities: Identity, Material Culture and Legitimacy in Venice, Ravenna and Rome, 750 –1000, Veronica West-Harling ed., Turnhout 2015, pp. 133–156, sp. p. 114.

68 The same can be observed, for example, for the nineteenth century reputation of the period of Gregory the Great, in relation to the Byzantinische Frage, see Giovanni Gasbarri, Riscoprire Bisanzio: lo studio dell’arte bizantina a Roma e in Italia tra Ottocento e Novecento, Rome 2015.

Řím mezi světlem a stínem

Nový pohled na „renesance“ a „dekadence“ v raně středověkém Římě

Římská kulturní produkce devátého a desátého století byla v historiografickém diskurzu vždy vnímána jako období „renesance“ následované dobou úpadku. Podobný výkladový rámec cyklického střídání vzestupu a dekadence je možné pozorovat již od raného novověku. Od zásadních textů Giorgia Vasariho proniká hluboko do dvacátého století. Autoři článku si kladou za cíl zamyslet se nad vznikem a používáním konceptu „středověkých renesancí“, a to na specifickém příkladu raně středověkého Říma a jeho umělecké produkce. Pohled na dějiny Říma se začíná polarizovat minimálně od dob konfesních polemik mezi protestanty a katolíky během šestnáctého a sedmnáctého století. V období protireformace vytváří postavy jako Cesare Baronio velmi specifický narativ, podle kterého je dějiny Říma možné hodnotit pozitivně či negativně na základě role papežů v daných obdobích. Pozitivně nahlíží na doby silných papežů. Z různých důvodů budou k podobným závěrům docházet i badatelé následujících století.

Kromě názorového střetu protestantů a katolíků však vstupují do tvorby historického narativu další prvky. Práci Richarda Krautheimera z poloviny dvacátého století, který hledá „renesance“ v umění římského středověku, je například možné chápat v kontextu jeho vlastního životního osudu. Krautheimer byl německým intelektuálem, který ve třicátých letech emigroval do usa Podobně jako v dalších případech intelektuálů je tak možné jeho touhu po renesanci, ve smyslu obnovy humanismu, vnímat jako reakci na druhou světovou válku.

Článek tedy poukazuje na to, že i historicko-umělecký pohled na materiální kulturu a umění Říma v devátém a desátém století je vázán na historickou zkušenost těch, kteří dějiny píší. Na straně druhé je však nutno podotknout, že se zde setkáváme s možná daleko hlubším archetypem: touha vykládat dějiny cyklicky je známa minimálně od Platóna a podle některých psychologů odpovídá niterným potřebám lidské mysli.

Abstract – Leading the Transition While Narrating the Passage. Papal Communication Strategies in the Early Eighth Century From a rereading the Liber Pontificalis and papal letters of the first half of the eighth century, this study analyzes certain aspects of the communication the papacy used to legitimize its political leadership in Italy and to build a network with the Franks. The paper’s focus is the emergence in the official documents of those years of the bonus pastor formula to describe the popes – a formula that enabled the pontiff to exploit pastoral semantics for political aspirations. Not only the documentary and narrative references, but also the monumental ones (the oratory of Saint Peter the Good Shepherd in the Vatican Basilica has been proposed to date to this period), have been analyzed and contextualized. The close relationship between the monumental and symbolic dimension of the Vatican, and its value to the communication strategies of the papacy, was thus emphasized. This is in relation to both the Franco-Papal alliance and the Italian and Roman context.

Keywords – Rome, Franks, papacy, Carolingians, Liber Pontificalis, Codex Carolinus, Lombards, St Peter’s Basilica

Parole chiave – Papato, Roma, Franchi, Carolingi, Liber Pontificalis, Codex Carolinus, Longobardi, Basilica di San Pietro

Andrea Antonio Verardi

University of Helsinki, Finland andrea.verardi@helsinki.fi

Narrare il passaggio, guidare la transizione

Strategie di comunicazione papale nella prima metà del secolo viii

Andrea Antonio Verardi

Il passaggio istituzionale di Roma e del suo Ducato dalla giurisdizione bizantina ad una papale sotto protettorato franco è un processo complesso, che cronologicamente trova le sue radici nel secolo vii ed ha i suoi più compiuti sviluppi nella prima metà del secolo viii. È in questo periodo infatti che, sulla scia di mutamenti politico istituzionali che riguardarono il territorio italico e il più ampio contesto euro-mediterraneo, ebbero avvio una serie di mutamenti che portarono i pontefici ad affermarsi quale autorità istituzionalmente e politicamente autonoma. Nella fluidità degli equilibri

sociali e politici italici infatti, tra gli anni trenta e cinquanta del secolo viii, i papi tentarono di stringere un legame, forte ma lontano, con i sovrani franchi, a discapito sia del tradizionale rapporto con Costantinopoli, sia dell’altrettanto percorribile alleanza con il regno longobardo, gettando così le basi per la nascita della Respublica Sancti Petri 1 In questa fase, in cui i rapporti tra le parti erano fortemente instabili, i vescovi di Roma,

1 Thomas F. X. Noble, The Republic of St. Peter. The Birth of the Papal State (689 – 825), Philadelphia 1982; Stefano Gasparri, Italia Longobarda. Il regno, I Franchi e il papato, Roma 2016.

preoccupati da un lato di difendere materialmente la città e la comunità che erano chiamati a guidare dalle pressioni Longobarde, e dall’altro di rivendicare con sempre maggiore insistenza spazi di autonomia in campo politico – spesso, come ha sostenuto Arnaldi, in maniera grettamente pragmatica – avviarono una fase di sperimentazione nelle strategie di comunicazione usate per favorire il raggiungimento dei propri scopi 2

Un percorso non del tutto coerente e, forse, non sempre volontario nei suoi avvii, ma, dati gli esiti, di sicura efficacia.

In questa occasione intendo focalizzare la mia attenzione su alcuni aspetti della comunicazione messi in atto dalla chiesa romana (congiuntamente dal papato e dall’ambiente del Laterano) per facilitare e legittimare il suo nuovo protagonismo politico all’interno del contesto italico e costruire un rapporto elettivo con i sovrani franchi.

Nel farlo prenderò in esame in particolare l’emersione nelle coeve fonti romane della rappresentazione del vescovo di Roma come bonus pastor. Una formula che, come ha messo in luce Ottorino Bertolini, si era affermata nell’uso degli ambienti lateranensi dopo gli anni Trenta del secolo viii e che permetteva al pontefice di utilizzare un’autorappresentazione di carattere pastorale per rivendicazioni politico istituzionali 3

Analizzerò dunque in primo luogo brevemente le fonti in cui questa espressione ricorre per la prima volta e il loro contesto redazionale, provando poi a valutarne la portata, soprattutto simbolica, all’interno delle strategie di comunicazione messe in atto dal papato sia in rapporto all’asse franco papale, sia nella sua dimensione locale, interna al contesto italico e romano.

Narrare il passaggio: il papato tra franchi, longobardi e bizantini nel Liber Pontificalis (715–767)

Gli eventi che portarono alla nascita del patrimonium Sancti Petri e ad una maggiore presenza dei franchi nelle vicende italiche ci sono noti principalmente grazie ad una manciata di fonti coeve, narrative e documentarie, di ambito franco e romano. Per il versante romano, come è noto, le nostre informazioni si riducono esclusivamente a dati

fornitici dalle biografie relative ai papi di questo periodo e contenute nel Liber Pontificalis

Si tratta, come è noto, di un’opera che aveva avuto la sua origine nel primo trentennio del secolo vi ed era stata poi proseguita, con qualche discontinuità, per i secoli vii e viii. Pur non essendo in origine un testo ufficiale del papato, esso era diventato sin dalla metà del secolo vi uno degli strumenti principali con il quale la chiesa romana (non sempre in sintonia con il suo vertice) rendeva pubblica una lettura “ufficiale” della sua storia. Il secolo viii segna per il Liber una nuova vivacità, dovuta con buona probabilità alla velocità di mutamento degli equilibri politico-istituzionali a Roma, nel Ducato e, più in generale nel contesto italico. Dinamiche queste che gli autori del Liber provano a seguire e, in alcuni casi, ad anticipare o direzionare con la loro narrazione 4. A questa dimensione di contesto, bisogna aggiungerne inoltre anche una di carattere strutturale, connaturale alla tipologia del testo indicato. Mi riferisco alle modalità stesse con cui il Liber veniva composto ed aggiornato –sebbene, ad oggi, ancora non del tutto chiare. La serie di biografie papali infatti era per natura aperta alle integrazioni ed agli aggiornamenti, non foss’altro che per la semplice aggiunta della biografia del pontefice in carica, o appena defunto, alla serie delle vite dei pontefici che lo avevano preceduto 5 Quest’opera di aggiornamento continuo, affiancata al carattere “aperto” del Liber, lasciavano ampi margini di intervento sul testo, sia a monte del processo di pubblicazione – cioè nella stessa Roma e negli ambienti lateranensi – sia presso coloro che ricevevano o copiavano le nuove biografie 6. Questo è particolarmente visibile nella sua tradizione manoscritta, dove a recensioni chiaramente identificabili, si affiancano tutta una serie di recensioni “miste”, caratterizzate non solo da una contaminazione tra le diverse famiglie redazionali, ma anche da aggiunte, più o meno estese a seconda dei casi, capaci di dare al testo “base”, nella sostanza, un tenore decisamente differente 7

Ciò è particolarmente visibile da un lato dalla presenza di alcune varianti significative all’interno delle biografie dei pontefici di questo periodo, che hanno fatto ipotizzare l’esistenza di tre diverse recensioni, così come alcune interessanti

sub-recensioni. Limitando la mia attenzione alle tre macro recensioni, la storiografia ha attualmente identificato una redazione cosiddetta originale, utilizzata dal Duchesne come testo base per la sua edizione, ed attestata solo in ambito italiano 8; e due altre recensioni, probabilmente esemplate sulla base di questa prima redazione 9, definite per le loro caratteristiche interne, rispettivamente Longobarda e Franca.

La prima, conservata in una serie di manoscritti databili tra la fine del secolo viii e il primo trentennio del ix, sarebbe stata realizzata sulla base della redazione originaria operando una revisione delle biografie che da Gregorio ii vanno a Stefano ii. Ciò sarebbe avvenuto probabilmente a Roma, tenendo presente un pubblico Longobardo. Questa versione infatti tende a presentare in maniera pressoché neutra le relazioni tra il papato e longobardi, eliminando sia gli accenti negativi che in alcune biografie appaiono nel definire l’intera gens, sia i riferimenti positivi ed enfatici riguardo ai sovrani franchi10

2 Girolamo Arnaldi, “Il papato e l’ideologia del potere imperiale”, in Nascita dell’Europa ed Europa carolingia: un’equazione da verificare, vol. i, Spoleto 1981, pp. 341–407.

3 Ottorino Bertolini, “Il problema delle origini del potere temporale dei papi nei suoi presupposti teoretici iniziali: il concetto di ‘restitutio’ nelle prime concessioni territoriali (756 –757) alla chiesa di Roma”, in Miscellanea Pio Paschini, studi di storia ecclesiastica, Roma 1948, pp. 103–171.

4 Di questo avviso già Lidia Capo, “Monaci e monasteri nella storia di Roma attraverso le fonti della chiesa romana (secoli vi–x)”, Reti Medievali Rivista, xix/1 (2018), pp. 315–316.

5 Abbiamo attestazioni esplicite di personaggi che erano in possesso di una parte della biografia del pontefice in carica e ne richiedevano l’aggiornamento, utilizzando intermediari che, recandosi a Roma, potevano avere accesso ad un testo aggiornato. Eclatante, in questo senso, il caso di Incmaro di Reims che chiese a Egilo di Sens in partenza per Roma di procurarsi lì l’aggiornamento del Liber, che egli possedeva sino alla prima parte della biografia di papa Sergio ii. La lettera è edita in Epistolae Karolini aevi (vi). Hincmari archiepiscopi Remensis epistolae, 1, (mgh, Epp. 8.1), a cura di Ernst Perels, Berlino 1939, n. 186, p. 194. Questa modalità di circolazione, quanto meno per questa fase, lascia suppore la presenza di una copia ufficiale o semi-ufficiale a Roma –il manoscritto brogliaccio ipotizzato da Lidia Capo, Il Liber Pontificalis, i Longobardi e la nascita del dominio territoriale della Chiesa romana, Spoleto 2009, p. 68. Una copia in costante aggiornamento e forse di facile reperibilità, se consideriamo il fatto che il richiedente dava per scontato che la sua richiesta potesse essere esaudita. Ciò lascia inoltre supporre che i testi delle biografie potessero circolare sciolti, o raccolti in fascicoli, non è chiaro se e quanto fosse forte e come fosse strutturato il controllo diretto da parte della chiesa romana di questo processo di aggiornamento. Gantner a tal proposito ha ipotizzato l’esistenza di libelli (Clemens

Gantner, “The Lombard Recension of the Roman ‘Liber pontificalis’”, Rivista di storia del cristianesimo, x [2013], p. 72 e n. 38), proposta che, sulla base dei gruppi testuali con cui circolano alcune biografie sembra poter essere probabile, sebbene la tradizione manoscritta non dia un’evidenza immediata e lampante di ciò. 6 È questo il caso ad esempio del codice attualmente conservato a Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek, 10.11 agosto 4°. Il manoscritto è stato scritto nel monastero di Wissembourg in Alsazia, in gran parte da un monaco di nome Waldmanno, ed è databile tra l’810 e l’830. Questo testimone contiene di base la cosiddetta redazione longobarda del Liber e presenta una lunga serie di note marginali aggiunte al racconto della vita di Stefano ii e di Gregorio ii, che ci permettono di ipotizzare un’integrazione di questa versione del Liber sulla base di un codice contenente la redazione cosiddetta franca. Probabilmente un fruitore contemporaneo del manoscritto, non credo per ragioni politiche, si era preoccupato di correggere l’intero testo a sua disposizione secondo una versione più aggiornata, o la cui origine fosse direttamente riconducibile a Roma. Cf. Andrea A. Verardi, “The Liber Pontificalis in the Age of Charlemagne: Considerations Around the Manuscript Tradition”, in The Manuscripts of Charlemagne’s Court School – Individual Creation and European Cultural Heritage, a cura di Michael Embach, Treviri 2020, pp. 387–408, sp. pp. 392–393.

7 In questo senso l’opera di edizione, per quanto filologicamente preziosa per precisare ed individuare alcune dinamiche di circolazione del testo, tende ad appiattire la vivacità del Liber di questa fase. Elemento questo che appare con lampante chiarezza nella materialità dei manoscritti, dove, in alcuni casi, mediante glosse, correzioni e aggiornamenti, le classi si mescolano e confondono, rendendo difficile condividere sino in fondo la classificazione nelle classi di manoscritti proposte dal Duchesne e dal Mommsen, minuziosa, sebbene spesso non completamente aderente alla complessità dei casi analizzati e, soprattutto, in alcune non convergente nelle due edizioni.

8 Gantner, “The Lombard” (n. 5), p. 70.

9 L’ipotesi di una rielaborazione del testo originario è pressoché accettata per la recensio franca, mentre più incerta è la lettura del rapporto tra questa e quella Longobarda. Mentre infatti Capo, Il Liber (n. 5) ha sostenuto, sulla base dei dati presenti nell’edizione del Duchesne e alla luce di un’analisi del testo in rapporto alla situazione politico-istituzionale del papato e del regno longobardo tra vii e viii secolo, che la recensio longobarda fosse il testo originale, dal quale sarebbe stato poi ricavato quello della recensio franca e del testo base di Duchesne, Gantner, “The Lombard” (n. 5) ha invece ipotizzato, attraverso un’analisi diretta e puntuale della tradizione manoscritta, la posteriorità della recensio longobarda rispetto alla redazione originale.

10 Sulla recensio Longobarda si vedano Capo, Il Liber (n. 5), pp. 73– 88; Gantner, “The Lombard” (n. 5); Clemens Gantner, Freunde Roms und Völker der Finsternis. Die päpstliche Konstruktion von Anderen im 8. und 9. Jahrhundert, Vienna/Cologna/ Weimar 2014, pp. 26 –38. I due studiosi pur riconoscendo l’esistenza di tre redazioni separate, giungono a conclusioni pressoché diverse. Lidia Capo infatti, su base storica e analizzando l’apparato critico del Duchesne, ipotizza che la recensio longobarda sia la prima redazione del Liber in questa fase e sarebbe stata realizzata a Roma all’interno degli ambienti lateranensi. Gantner invece, analizzando la tradizione manoscritta delle biografie interessate da una triplice redazione sostiene che la recensio longobarda sia una rielaborazione del testo “originale”, databile tra il 758 e il 780, più precisamente tra la fine degli anni Cinquanta e i Sessanta del secolo viii.

L’altra recensione sarebbe stata composta anch’essa a Roma sulla base della redazione originaria, privilegiando un parterre prevalentemente franco. Essa è caratterizzata da rielaborazioni testuali (interpolazioni e correzioni grammaticali), che interessano in particolare le biografie di Gregorio iii (731–741), Zaccaria (741–752), Stefano ii (752–757) e Paolo i (757–767), e che hanno lo scopo di sottolineare la forza del rapporto tra i Franchi e il papato e screditare il potere lombardo 11. Inoltre, essa avrebbe avuto lo scopo di includere i carolingi nella rappresentazione ideologica della storia papale, al fine di sostenere e legittimare la loro acquisizione del potere all’interno del regno franco, e motivare una loro maggiore presenza nelle vicende italiche12

Come è facilmente intuibile, dunque, ci si trova di fronte ad un’opera complessa, esito di una rielaborazione volontaria e spesso funzionale ai mutevoli equilibri politico-istituzionali coevi, sulla quale la dimensione pubblicistica ha giocato un ruolo centrale 13. Questo è macroscopicamente visibile nelle modalità con cui le diverse redazioni del Liber hanno ricostruito la sequenza degli eventi e descritto gli equilibri in campo in questa fase di passaggio.

La lettura della situazione italica a ridosso del primo intervento franco ci è fornita dalla biografia di papa Gregorio ii (715–731), giuntaci in due differenti redazioni. Una prima, redatta intorno al 731, e poi utilizzata dal redattore della recensio longobarda, in cui i franchi non sono mai menzionati, e nella quale l’azione del pontefice si svolge interamente in una dimensione italica, giocata tra resistenze antibizantine e opposizioni romane alle mire espansionistiche dei Longobardi. E una seconda, invece, realizzata come riscrittura della prima, introno al 74014. Tra gli attori in campo troviamo Costantinopoli, rappresentata in tutte e tre le redazioni nel pieno di tensioni politiche (alternanza sul trono imperiale dell’ortodosso Teodosio e l’eretico Anastasio) ma, soprattutto, descritta con accenti nel complesso negativi.

Al potere greco il Liber contrappone le genti italiche, rappresentate da tutti i redattori come schierate con il pontefice. Un appoggio, quello dato al pontefice, che nelle ricostruzioni delle tre redazioni, è reso ancor più compatto quando alla

dimensione politico-istituzionale, si sovrappone quella religiosa15. Nella narrazione del Liber è intatti l’iconoclasmo a rendere il papa il rappresentante delle genti italiche ed innescare una forte opposizione contro l’imperatore, tanto che questi si erano spinti al punto di pensare di eleggersene uno proprio ed è solo la mediazione papale ad impedire che ciò avvenga 16

Un ruolo centrale nella ricostruzione è svolto anche dai Longobardi, intesi nelle loro differenti articolazioni politiche – sovrano e duchi di Spoleto e Benevento, spesso però rappresentati dal Liber unitariamente. Le due versioni della biografia seguono l’evoluzione degli equilibri in gioco, leggendo le relazioni tra le fazioni longobarde sia al loro interno, sia nel rapporto con il papato, e ne sottolineano, a tratti, la vicinanza ai pontefici e alle genti italiche17. Essi sono al fianco dei Romani nella difesa del pontefice18, ma non esitano comunque a passare dalla parte degli oppositori del pontefice, attaccando alcune città del Ducato e la stessa Roma, stringendo un patto con l’esarca e contro il pontefice19. Salvo recedere poi dai propri intenti di fronte alle preghiere di Gregorio ii, con Liutprando che, in atto di devozione, si spoglia delle proprie insegne per deporle sulla tomba dell’apostolo Pietro 20. Predatori del ducato romano, o eroici alleati del papato e dei romani, i longobardi non appaiono in entrambe le redazioni della biografia di Gregorio ii comunque con una connotazione del tutto positiva 21

Ciò vale in particolare per l’oscillazione nella rappresentazione delle decisioni in campo politico del sovrano longobardo, che non credo siano dovute alla sola faziosità della ricostruzione offerta dagli autori del Liber, ma riflette tutta la complessità di una situazione fluida in cui piani diversi (politico, umano e religioso) si sovrapponevano influendo tanto sulle alleanze politiche, quanto sulle azioni personali 22. Attribuibile agli autori del Liber è però la volontà di non dare mai un valore completamente positivo alle azioni di Liutprando. Ciò è probabilmente dovuto ad una scelta ideologica compiuta dagli autori di questo testo, i quali scrivono subito dopo gli eventi narrati, per stigmatizzare una serie di rapporti politici che, nella prima metà del secolo viii, erano ancora ampiamente percorribili.

Al fianco di questi poi si inseriscono una serie di personaggi per certi versi minori, come il

Tiberio Petasio, citato nella sola redazione Franca 23 Questo personaggio si era sollevato nella Tuscia romana, cioè nell’area a Nord di Roma, rivendicando a sé il titolo di Imperatore, riuscendo ad ottenere un certo seguito tra la popolazione locale. Secondo la narrazione del Liber, l’esarca sarebbe stato turbato dalla vicenda, ricevendo però il sostegno del pontefice, che inviando le proprie truppe ( proceres ecclesiae atque exercitusi) contribuì decisivamente alla repressione dell’insorto 24

La notizia, come ha notato Noble, contribuisce, tra le altre cose, a sottolineare da un lato la precarietà del potere dell’esarca, e, di conseguenza di Costantinopoli, in Italia; dall’altro il ruolo di preminenza assunto dal pontefice anche in campo politico (capacità di intervento papale anche al di fuori del contesto strettamente cittadino; subordinazione dell’E sarca al Pontefice nell’esercizio di una qualche forma di potere all’interno della città di Roma) 25

Un qualche cambiamento nelle modalità di narrazione del Liber si ha con la biografia successiva, quella di Gregorio iii (731–741) 26. Nella versione “originale” della biografia, l’unica notizia di carattere meramente politico è rappresentata dalla descrizione dell’azione papale volta a porre fine alle contese tra il ducato romano e quello di Spoleto, riguardo al possesso del castro di Gallese 27 , che il pontefice recuperò in compage sanctae reipublicae atque corpore Christo dilecti exercitus romani 28 Diversa è invece la rappresentazione offerta dalle integrazioni contenute nella cosiddetta recensione franca, nelle quali l’autore, oltre ad offrire

11 François Bougard, “Composition, diffusion et réception des parties tardives du Liber Pontificalis (viiie–ixe siècle)”, in Liber, Gesta, histoire. Écrire l’histoire des évêques et des papes, de l’Antiquité au xxie siècle, a cura di François Bougard, Michael Sot, Turnhout 2009, p. 138 ; Gantner, “The Lombard” (n. 5), p. 71.

12 Sulla recension franca si vedano Rosamond McKitterick, History and Memory in the Carolingian World, Cambridge 2004, pp. 32–334, sp. pp. 144–148; Gantner, “The Lombard” (n. 5); Carmela Vircillo Franklin, “Reading the Popes: The Liber Pontificalis and its Editors”, Speculum, xcii (2017), pp. 607– 629. Sulla circolazione del Liber in area franca tra la metà del secolo viii e i primi decenni del ix si veda, oltre al testo appena citato, Verardi, “The Liber” (n. 6).

13 Di questa idea Capo, Il Liber (n. 5), p. 303–314, contrario Gantner, “The Lombard” (n. 5), p. 68, n. 17.

14 Le Liber Pontificalis, a cura di Louis Duchesne, vol. i, Parigi 1886. Sulle differenti redazioni della biografia si vedano Bougard, “Composition” (n. 11), p. 138; Gantner, “The Lombard” (n. 5), p. 71.

15 Noble, The Republic (n. 1), pp. 28 –41.

16 lp (n. 14), pp. 404–405.

17 I Longobardi appaiono per la prima volta, come entità politicamente indistinta, nella biografia di Gregorio ii quali invasori del Ducato di Roma, come nel caso del Duca Romualdo ii di Benevento (lp [n. 14], p. 400) o di re Liutprando (ibidem, p. 403). Essi assumono però un ruolo centrale nella rivolta italica contro Bisanzio e i suoi rappresentati, in seguito all’imposizione di nuove tasse per sostenere le campagne anti-saracene, su questo Gantner, Freunde (n. 10), pp. 84– 87.

18 Nella crescente tensione tra Roma e Bisanzio, che caratterizzò i primi tre decenni del secolo viii, i longobardi (rappresentati sempre senza distinzione tra Duchi e re), intervennero a favore del papa e dei romani a difesa degli attacchi mossi a Roma dall’esarca Eutichio. In questo caso, come riportano concordemente entrambe le redazioni del Liber, essi resistettero anche ai tentativi di corruzione da parte di Eutichio, in virtù di una comunanza di intenti e valori con i romani, come segnala lo stesso Liber: “una se quasi fratres fidei catena constrinxerunt Romani atque Longobardi” (lp [n. 14], p. 406).

19 Tra il 727 e il 729 il sovrano longobardo attaccò prima Sutri, e poi la stessa città di Roma permettendo l’ingresso dell’esarca in città, fungendo da mediatore tra Eutichio e il papa, per il raggiungimento di un accordo amichevole. In questo caso, però, entrambe le redazioni fanno riferimento all’azione del solo re Liutprando. Secondo la redazione “originale” della biografia di Gregorio, il sovrano sarebbe intervenuto nella regione per spezzare l’alleanza stretta dal papa con i duchi di Spoleto e Benevento e riportare quest’ultimi sotto la sua autorità. Cf. in generale Noble, The Republic (n. 1), pp. 34–37; con particolare riferimento al Liber Gantner, Freunde (n. 10), pp. 141–142; sul ruolo svolto da Liutprando si veda Walter Pohl, “Das Papsttum und die Langobarden”, in Der Dynastiewechsel von 751. Vorgeschichte, Legitimationsstrategie und Erinnerung, a cura di Matthias Becher, Jörg Jarnut, Münster 2004, pp. 145–161.

20 lp (n. 14), pp. 407–408 (entrambe le redazioni); Gasparri, Italia Longobarda (n. 1), p. 89.

21 Gantner, Freunde (n. 10), pp. 140 –145.

22 Pohl, “Das Papsttum” (n. 19), p. 146 e ss.

23 lp (n.14), pp. 408 –409 (colonna di destra).

24 Noble, The Republic (n. 1), p. 37.

25 Ibidem

26 lp (n. 14), pp. 415–425.

27 Il castro controllava il percorso che da Roma conduceva a Ravenna e svolgeva dunque un ruolo centrale da un punto di vista militare. Tra il 737 e il 738 esso era stato occupato dal duca di Spoleto Trasamondo ii, alla ricerca di autonomia rispetto al regno e tradizionalmente alleato dei pontefici contro il sovrano longobardo, come reazione alle campagne di Liutprando nei confronti della Pentapoli. Su Trasamondo vedi François Bougard, “Trasamondo ii”, in Dizionario Biografico degli italiani, vol xcvi, Roma 2019 [http://www.treccani.it/ enciclopedia/trasamondo_%28Dizionario-Biografico%29/].

28 lp (n. 14), pp. 420 –421. Capo, Il Liber (n. 5), p. 182 e ss., sottolinea in questo caso che la rappresentazione offerta da questa versione del Liber permette di ipotizzare la persistenza del riconoscimento a Roma del quadro istituzionale imperiale (la sancta respublica), ma allo stesso tempo di individuare la nascita di una componente nuova, quella dell’esercito. Un’entità autonoma che è riconosciuta come tale dal papa e che, a sua volta, riconosce l’autorità di quest’ultimo.