By Adrian Patrut

By Adrian Patrut

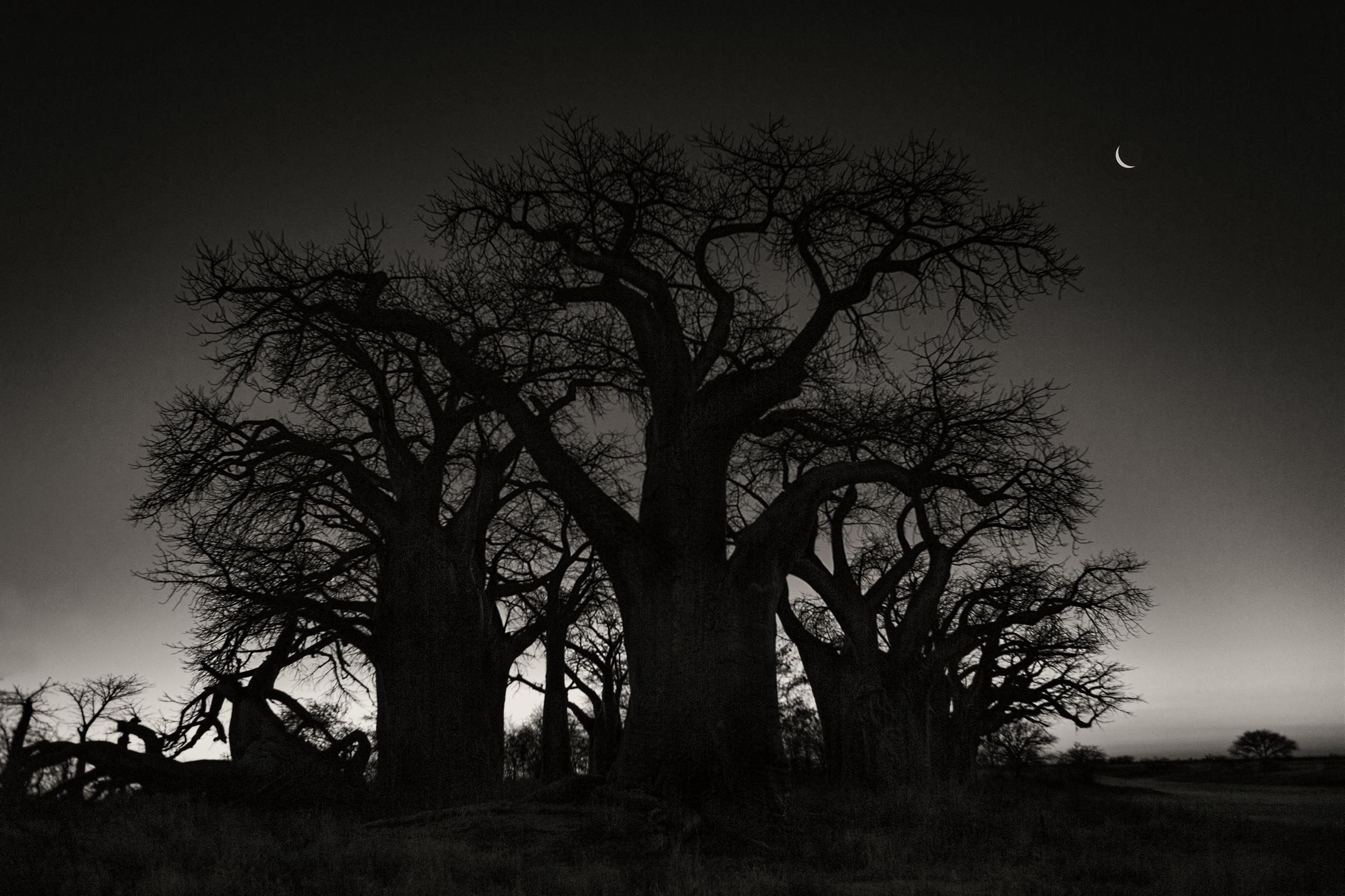

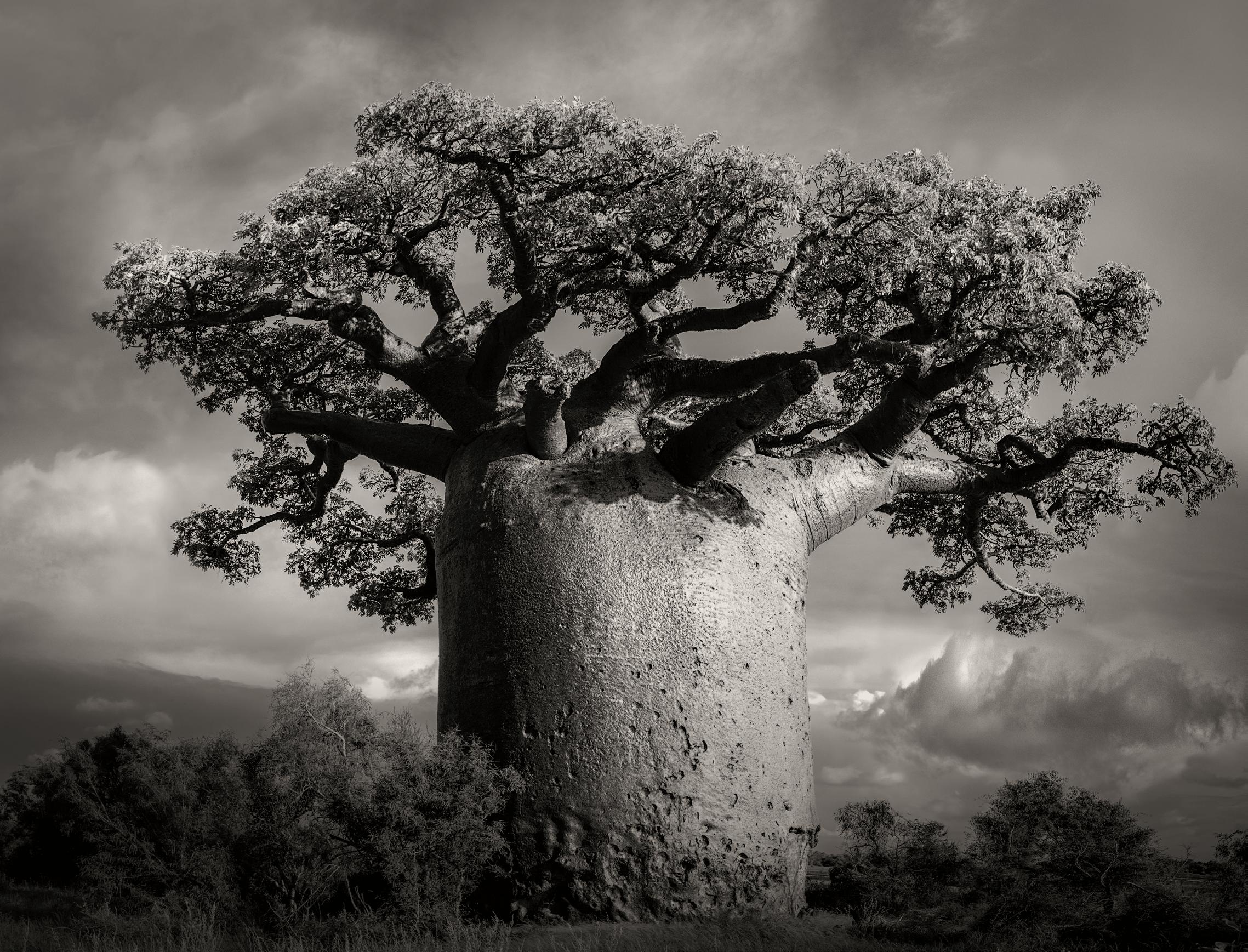

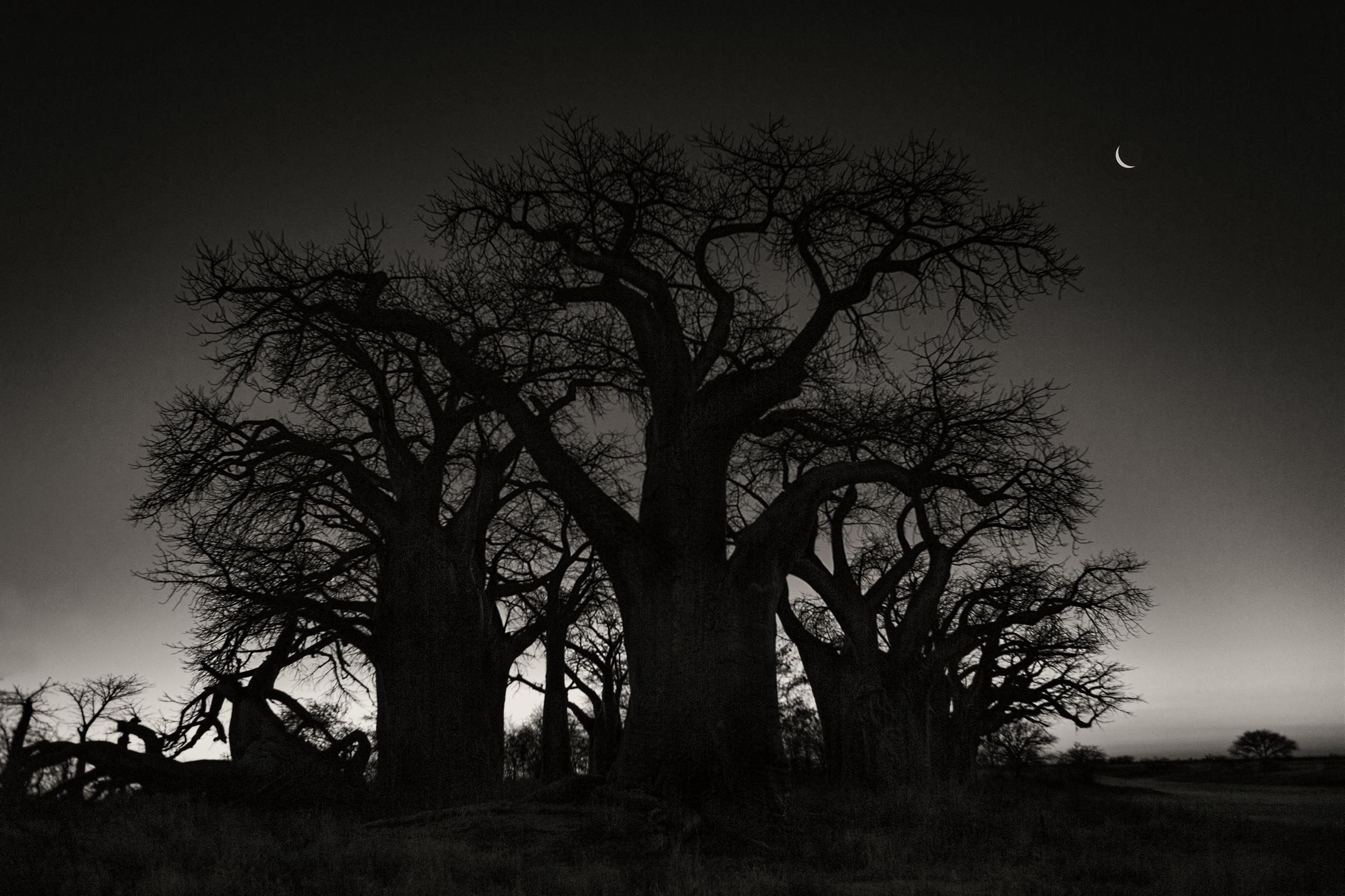

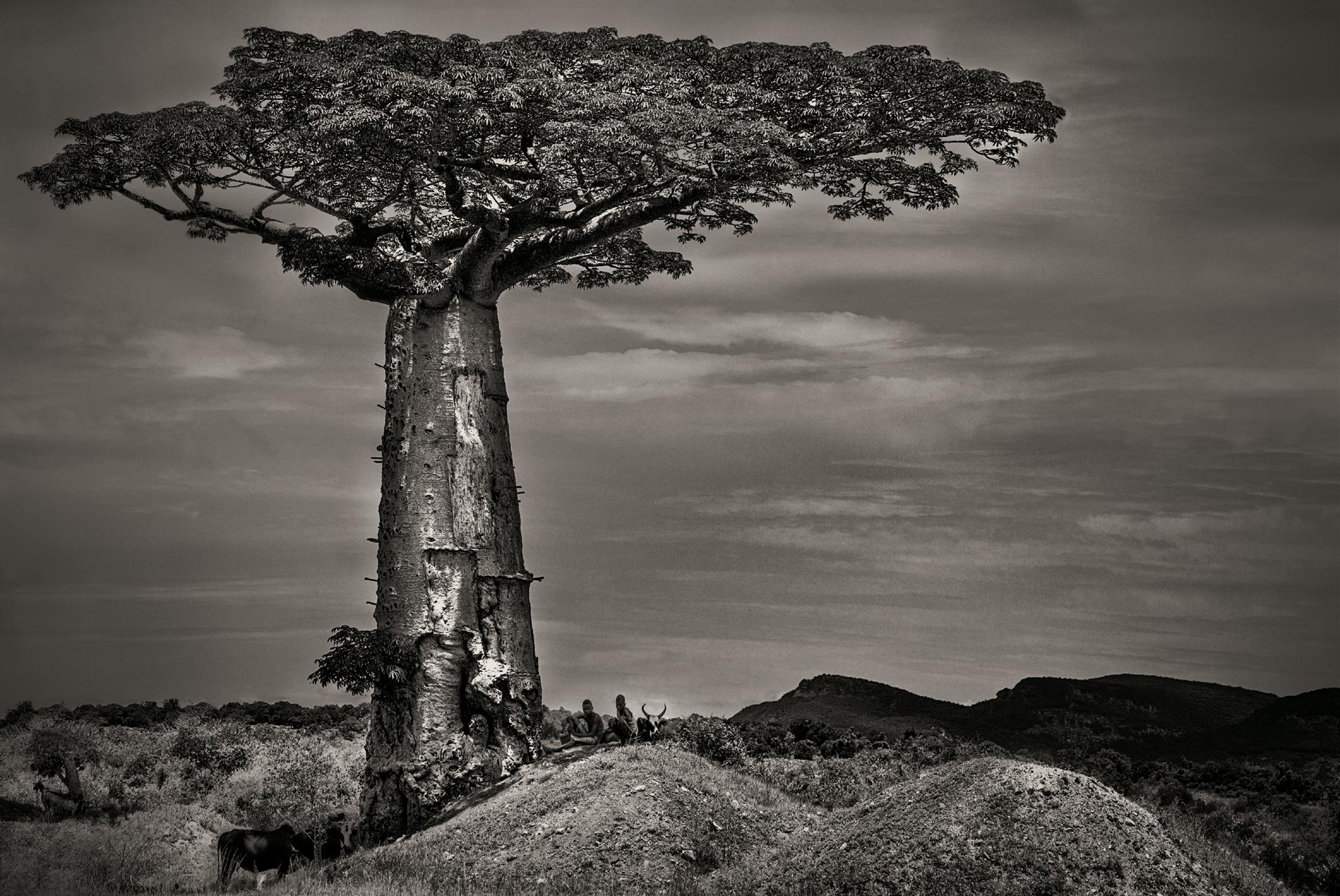

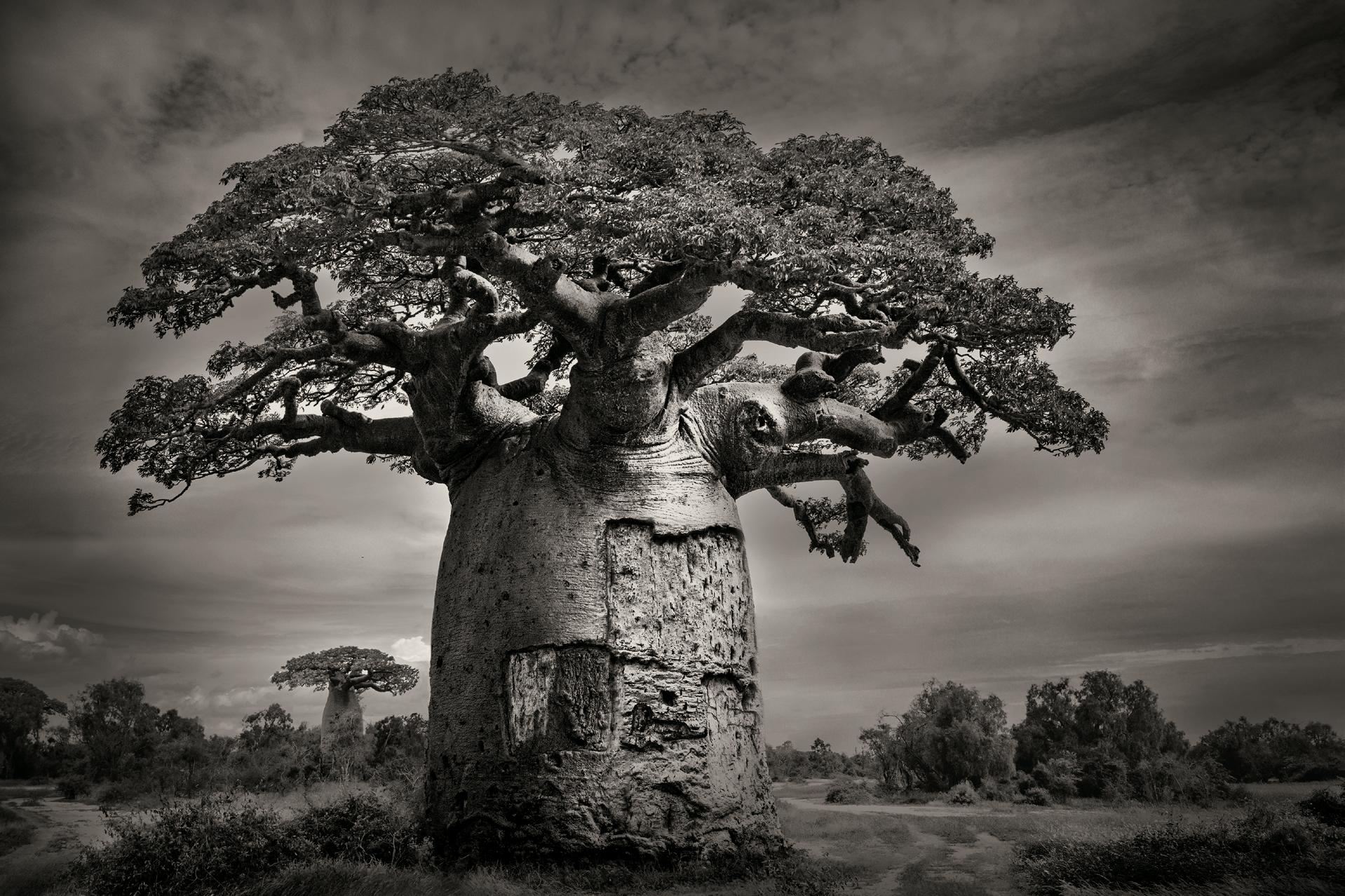

Cut off from the rest of the world, this ancient island in the Indian Ocean will seduce even the most jaded visitor. A land of endless vistas and lush forests, Madagascar is defined by its unique wildlife, by grand, dramatic gestures found in curling branches and extravagantly sized trunks of gargantuan measure.

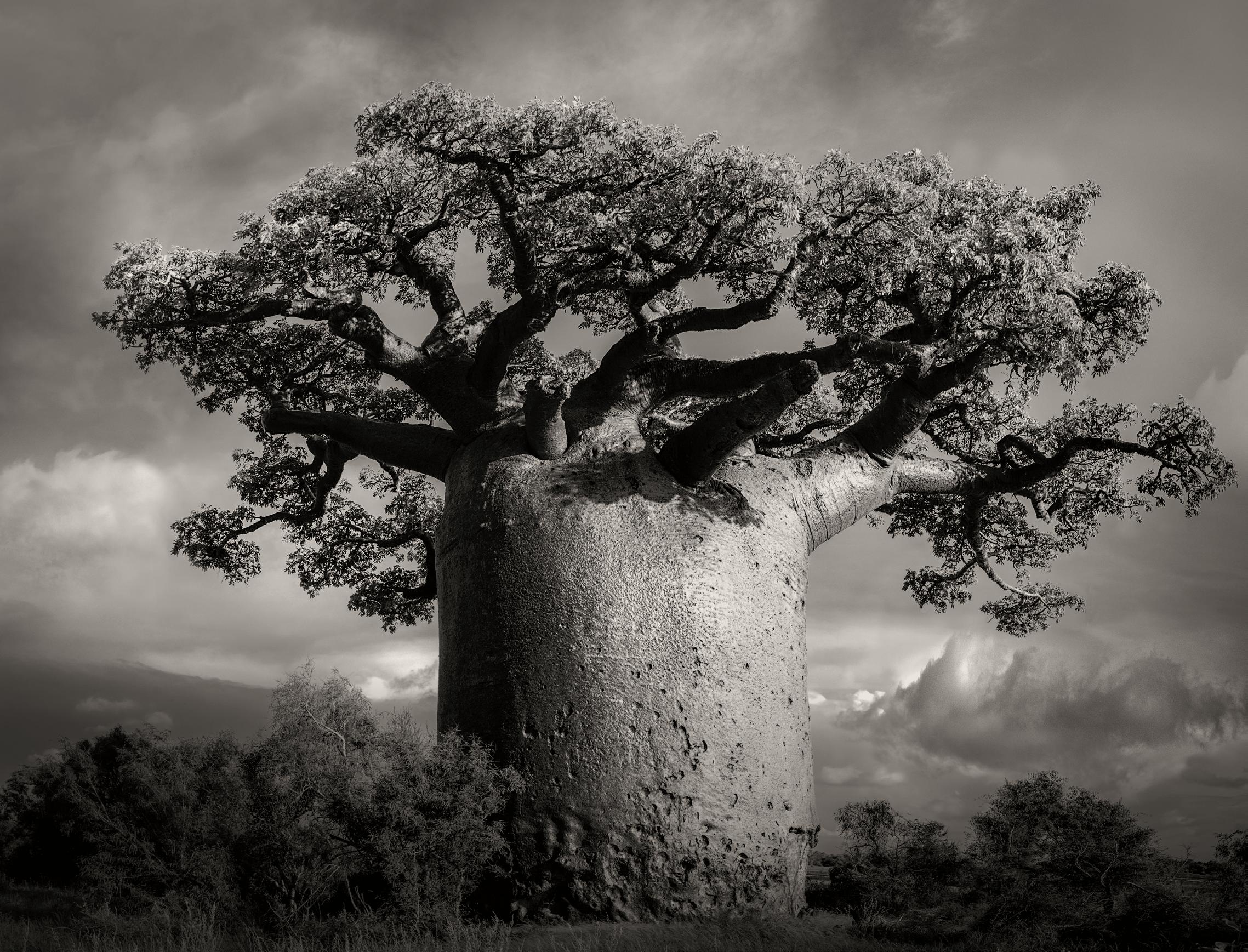

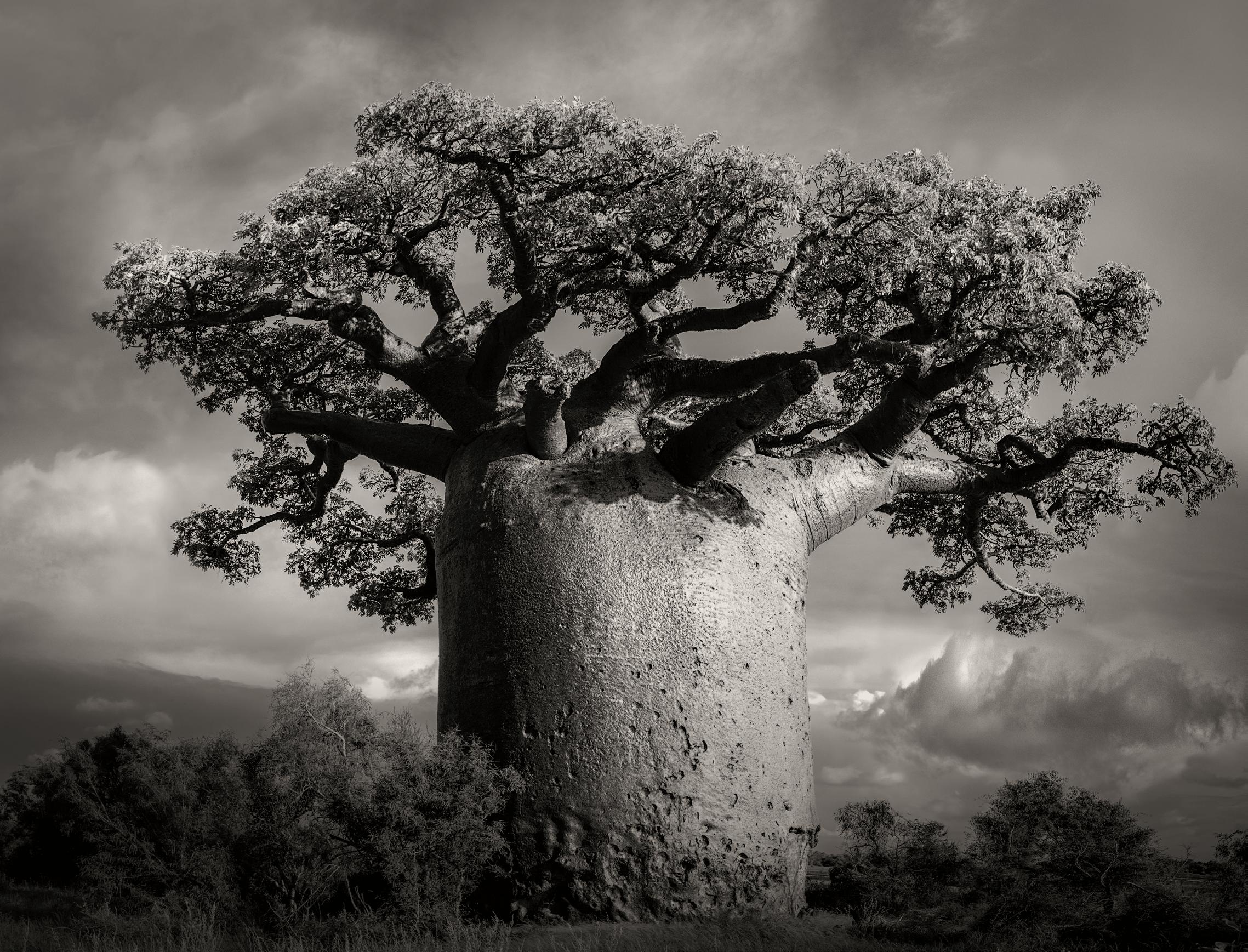

Throughout the millennia, Baobab stands engaged and present, an alchemist dressed in leaves and bark, reminding us that beauty comes with great age.

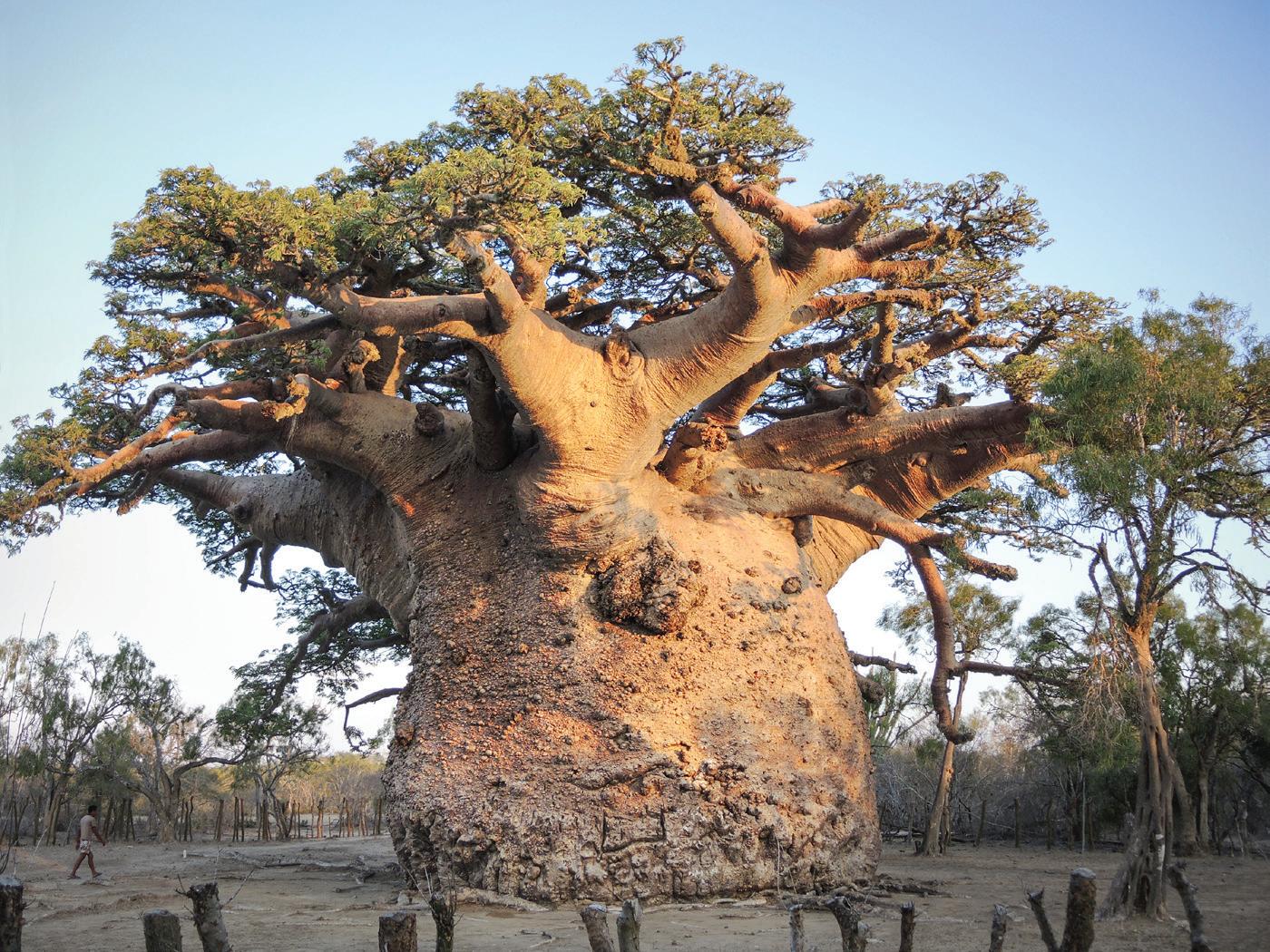

When the Malagasy speak of Baobab, they do so with respect, their eyes looking upward, for the gifts he gives are many. He shelters, feeds, and cures all.

After long hours in the hot African sun, squint, and you will see a motley crew of grizzled titans resembling milk jugs, teapots, and flower vases. But be careful not to stay in the forest too long. Baobab will bewitch you.

What follows is the story of my journey to this exotic island where magic, miraculous beauty, and some of the oldest trees exist.

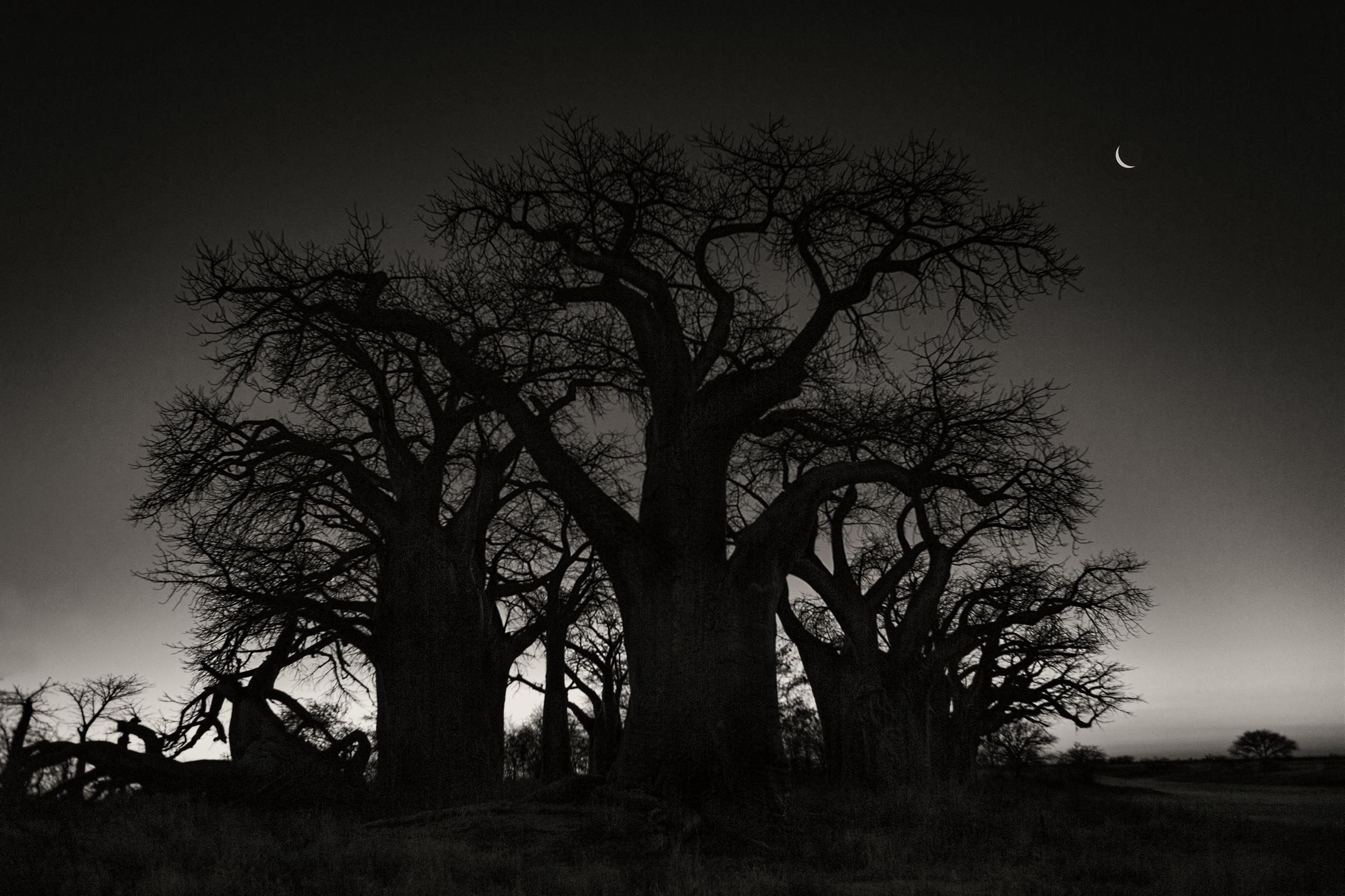

In January 2016, a thunderous boom was heard. One of Africa’s oldest trees, Chapman’s Baobab, had collapsed. Memories of my visit to the tree two years earlier flooded my mind. It is hard to believe; the tree had looked so strong and healthy.

Then, in June 2018, shocking headlines began to appear in global media.

Last March of the “Wooden Elephants”:

Africa’s Ancient Baobabs Are Dying

—The New York Times

Baobabs Are Africa’s Oldest and Most Beautiful Trees, But They’re under Threat

—The Independent

Shocking and Dramatic Death of Giant African Baobab Trees Possibly Linked to Climate Change

–The Daily News

The guide who had led me to various locations throughout Botswana writes to tell me the trees that we camped under at Kubu Island have collapsed. “From the cluster of trees on the NE side, at least two have fallen,” he reports.

Adrian Patrut, a professor of inorganic radiochemistry at Romania’s BabesBolyai University, and his team have been measuring, radiocarbon dating, and documenting the largest and oldest trees in the Southern Hemisphere for the past decade. Professor Patrut and I have been sharing information on trees for several years.

On November 3, 2018, I receive an email from Professor Patrut telling me that he has received news from Madagascar. He writes, “The Tsitakakoike baobab, the biggest sacred baobab, split and toppled several days ago.”

Thinking of the trees, I am filled with anxiety. How can I ignore the onslaught of information directed to my notice? Do I move ahead in indifference? Sleepless nights indicate otherwise.

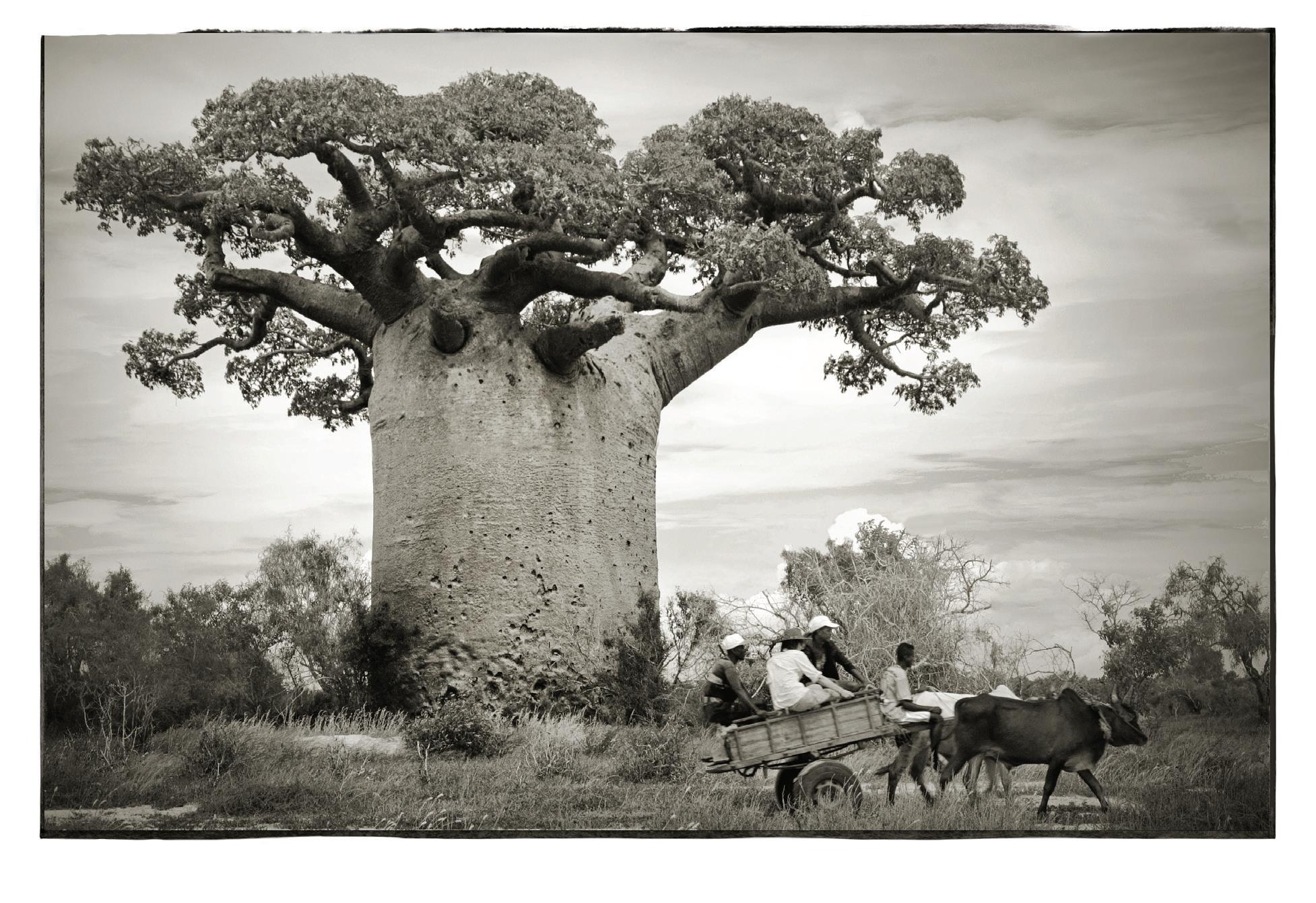

Our group is now six people with one tiny cart, although Tsimizaotra and Mbohirahy walk most of the way, keeping a watch on the forest. The zebu are phenomenal beasts, treading through water and mud without difficulty.

The forest appears to spread over a landscape of broad and narrow valleys. We stop as the men discuss the best paths to take. Moisture hangs in the air, and verdant leaves glisten.

We are cramped in the cart in periods of heavy downpour. When the path becomes very narrow amid the brush, I am slapped in the face with branches laden with insects and rain, since I am the first passenger behind the driver. I do not want to change my place in the cart, however, as it allows me to see the view ahead, and this is most important. Frequent downpours are exuberant, and suddenly we find ourselves surrounded by towering giants.

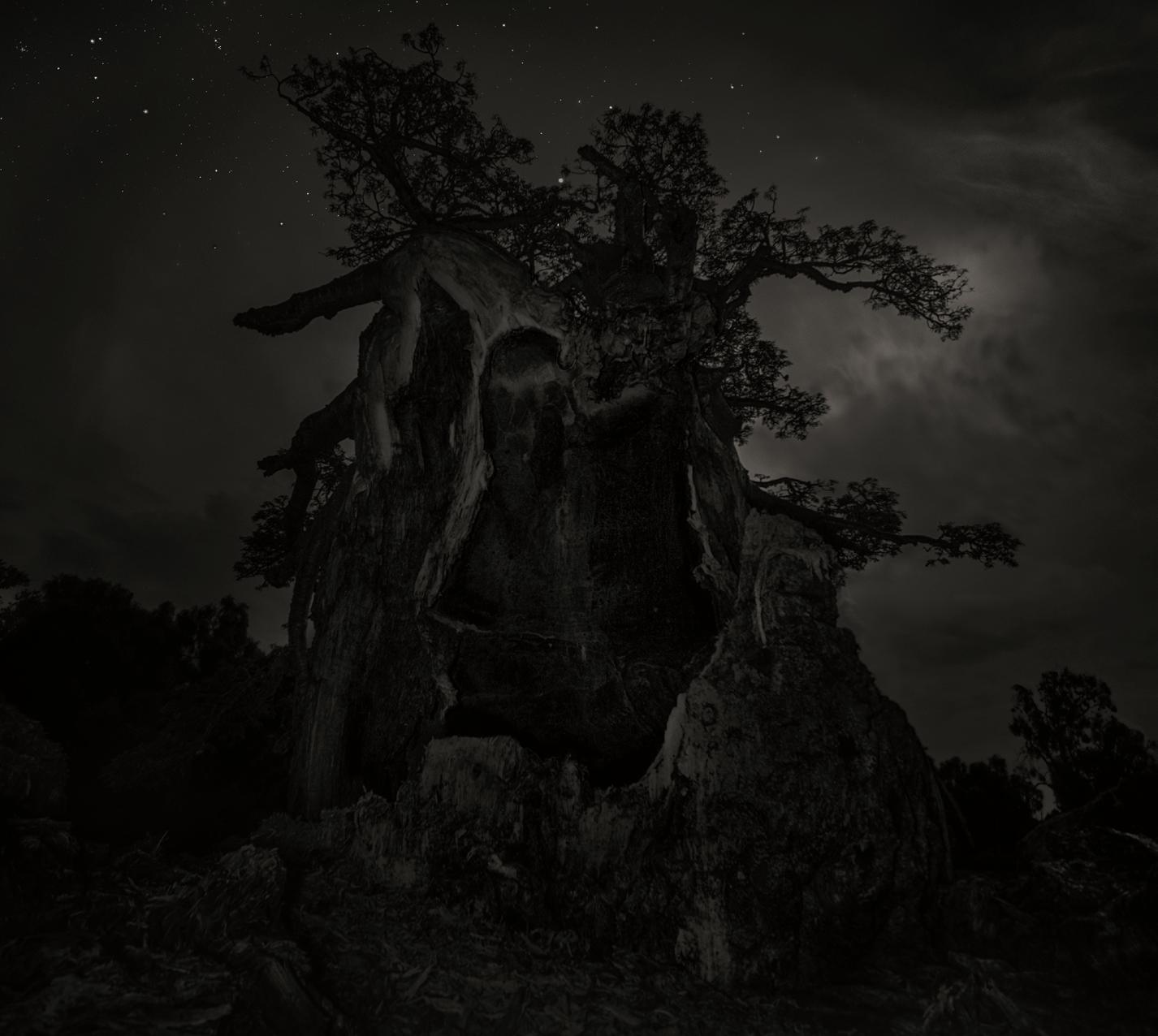

Astonishment and horror set in as Tsitakakoike comes into view. Half of the tree has collapsed; a portion of the sides and back of the trunk remain. Gigantic branches, larger than most trees, lay in disarray at the base of the trunk. The entire spectacle is about the size of a football field.

From this perspective, we get a glimpse of the astonishing metaphor this image presents—amid the wreckage, some vibrant green leaves remain, a fragile and ephemeral sign of life. I stare at the unfolding tragedy before me with horror. Grand in deterioration, it is all so hard to comprehend.

Exposed roots signify drought; the rains have come too late. It will take a few weeks, maybe a month, before the tree collapses entirely.

The broken trunk exposes the heart of the tree.

Heartwood, by definition, is the older, nonliving central part of the tree, usually darker and harder than the younger sapwood. Its main function is to support the tree.

The heartwood could no long support the tree.

Hand on my heart steadies the beating in my chest.

The words of Jane Hirshfield come to mind.

Today, for some, a universe will vanish.

First noisily, then just another silence.

The silence of after, once the theater has emptied.

Of bewilderment after the glacier, the species, the star.

Something else, in the scale of quickening things, will replace it,

The hole of light in the light, the puzzled birds swerving around it.

—“Today Another Universe”

I approach the tree through knee-deep water that has accumulated from recent rains. With each step forward I am pulled toward a miraculous sight. I can clearly sense the radiance and magic this tree projects.

Senegal is a fascinating and vibrant country. The Senegalese hold a special place in their hearts for the baobab tree—it is greatly loved. Along with the lion, the baobab is the country’s national symbol. Many villages and communities have been constructed around large baobabs, which mark the central public square.

Today, however, Senegal’s baobabs are threatened by climate change and urbanization. I see evidence of this driving down the coast from the capital, Dakar. Bandia, one of Senegal’s most beautiful baobab forests, is gradually being devoured by limestone quarries.

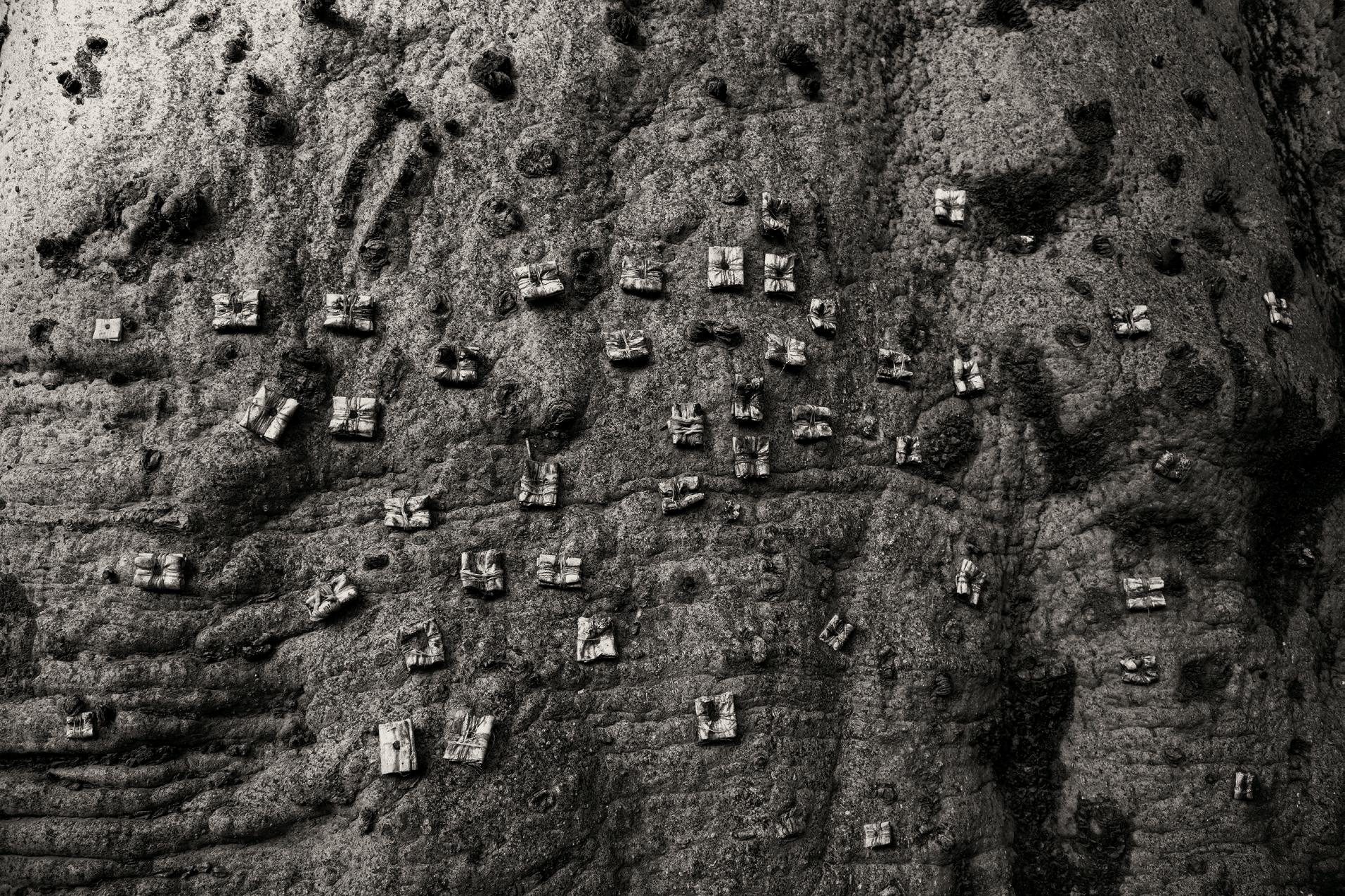

This tree is regarded as divine by the people of Nianing village. Its bark is studded with hundreds of nails. Villagers visit a traditional healer who writes their hopes and wishes on paper. The paper is folded into a tiny parcel, tied with thread, and nailed to the trunk.