I. Vajra and Ghaṇṭā

The Diamond Sceptre and the Bell .................................................................

1. The crossed double-vajra ..................................................................

2. Ghaṇṭā – The handbell .....................................................................

II. The Eight Auspicious Emblems

Ritual Objects of the Buddhist Law ...............................................................

III. Precious Jewels and Offering Symbols ..............................

1. Ratna and Cintāmaṇi – Auspicious jewels and wish-gran ng gems.....

2. The Offerings of the Five Senses .......................................................

IV. The Stūpa as a Ritual Object ...................................................

V. Maṇḍalas

A Three-Dimensional Cosmogram as a Ritual Object ....................................

1. The three-dimensional maṇḍala .......................................................

Cloisonné maṇḍalas ...................................................................

2. The lotus maṇḍala ............................................................................

3. Altar table maṇḍalas .........................................................................

4. The sand maṇḍala ............................................................................

5. Portable maṇḍala plaques ................................................................

6. The Buddhist yantra ..........................................................................

VI. Offering Vases and Vessels ......................................................

1. Consecra on and ini a on vases .....................................................

2. Treasure vases ..................................................................................

3. Treasure caskets ................................................................................

4. Longlife vases ....................................................................................

5. The seven water offering bowls ........................................................

6. Offering lamps ..................................................................................

7. Liba on vessels – Drink offerings for the protectors ........................

8. Jewel offering bowls .........................................................................

VII. Tormas and Bu er Decora ons ........................................... 135

1. Tormas – Colourful symbols and sacrificial offerings ........................ 135

2. Bu er sculptures – Monumental tormas for sacred performances ... 143

VIII. Prayer Objects of Popular Buddhism ............................... 149

1. The mantra wheel ............................................................................ 149

2. The mālā – A Tibetan rosary ............................................................ 152

3. Maṇi-stones and mantras ................................................................ 154

IX. Ritual Magic Weapons ............................................................... 159

1. Phurba – The magic dagger .............................................................. 161

2. Khaṭvāṅga and triśūla – The tantric staff of saints and sadhus ......... 182

3. Daṇḍa and gadā – Sceptre of power and punishment ..................... 196

4. Vajra hammer – Ritual weapon defea ng the evil ............................ 201

5. Paraśu axe – For divine destruc on .................................................. 204

6. Aṅkuśa – The vajra goad hook for control and discipline ................. 206

7. Kaṛtrikā: The chopper knife – Cu ng off a achment and delusion ... 208

8. Vajra sword and tantric spear ........................................................... 214

8.1 The vajra sword – From warfare to wisdom ............................... 214

8.2 The tantric spear – Emblem of power and protec on ............... 217

9. Arrow and bow – A ributes or ritual implements? .......................... 218

10. Pāśa noose and hook – Binding demons and delusions ................... 220

X. Spirit Traps and Magic Mirrors ................................................ 225

1. The thread-cross – Catching the evil and protec ve magic .............. 225

2. The magic mirror – Reflec ng the truth, projec ng the void ........... 228

XI. Special Ceremonial Objects .................................................... 237

1. Homa-fire ritual tools ....................................................................... 237

2. Kapāla – Skull-cup for Inner Offerings .............................................. 248

3. Bone ornaments – For tantric gods and prac oners ...................... 259

4. The magic horn – For sorcery and exorcism ..................................... 264

5. Tripod offering stand ........................................................................ 266

6. Incense burner – For purifying and consecra on ............................. 269

7. Rinchen serdar – For rubbing auspicious metals .............................. 275

8. Ritual tongs – For wrathful rites ....................................................... 278

9. Skulls and skeletons – For divine defence and fierceful protec on .... 280

9.1 Tantric iron curtains ................................................................... 280

9.2 Skull palaces for secret ini a on ................................................ 283

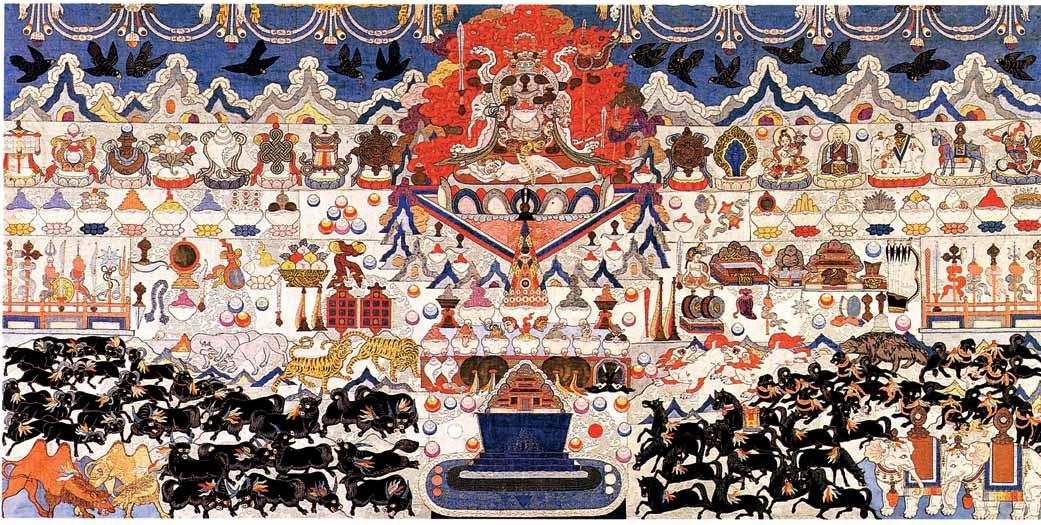

Fig. 4 Kangdzä offering thangka for Mahākāla. Silk appliqué, ht. 133.5 cm, w. 256.5 cm. Mongolia, ca. 19th century. The unusual image type of a painted or silk kangdzä (bskang rdzas), also known as, and associated with, an “assembly of ornaments” (rgyan tshogs), is a collec ve visual offering for the wrathful protector dei es in the secret and o en restricted gönkhang (mgon khang) shrine in a Tibetan temple, where these tantric divini es and magic forces are ritually invoked and ac ve. This large pain ng is dedicated to Mahākāla with a red fire-flaming wisdom aureole, the foremost divine guardian of Gelugpaoriented Mongolia, represented here in a largely non-figural form when trampling upon a naked corpse, and thus defea ng and conquering outer and inner evils. As described in ancient tantric texts (Sādhanas), the “wrathful triangle” symbolises violent ac on and recalls the homkhung iron-pit imprisoning and elimina ng the mental poisons such as desire, aversion, and ignorance (see Ch. XI.1).

Flayed animal skins, severed human heads and skulls, bowls with fruit offerings, choppers, swords and spears, conch horns and musical instruments, mirror and pāśa noose, phurba and triśūla khaṭvāṅga, vajra axe and hammer, daṇḍa club, precious jewels and astrological diagrams, the Eight Auspicious Emblems and the Seven Jewels of Royal Power torma, blood and nectar-filled kapāla offerings of the Five Senses are represented around cosmic Mount Meru, imago mundi and centre of the universe between heaven and earth, a whole pictorial encyclopaedia of ritual objects and symbols. Photo courtesy Zanabar Museum of Fine Arts, Ulan Bator, Mongolia.

documen ng, researching and exhibiting tantric Buddhist art and artefacts from Tibet and Japan. A er some early contacts with the 16th Karmapa Rangjung Rigpai Dorje (1924–1981), and later with Professor Roger Goepper in the field of esoteric Shingon Buddhism, the eminent Ngari Tulku Tsering Tashi Thingo (1945–2008) gave essen al inspira on for the collec ons of the foundaon. Beyond the criteria of aesthe cs and “fine art”, the BODHI MANDA’s priori es are ritual meaning and context, spiritual and symbolic background, as well as the medita onal aspects of the

objects, seen with a mindful inner eye, in order to reconstruct a temple se ng as an iconological and ceremonial en ty.

Although I have been in close contact with the BODHIMANDA FOUNDATION for years, I had access to the en re collec on only in late 2015, when I was able to see and select the many “hidden treasures” being kept in storage at the Ro erdam Wereldmuseum.3

“Ritus” (from which the word ritual is derived) in La n means “the right way”, right doing or ac on according to tradion and to certain standardised conven ons and rules. The Indian Sanskrit

equivalent would be pūjā for a religious ritual in general, in a broader meaning, offering, worship and venera on of the gods. Rituals define and structure daily spiritual life, and in India and Tibet in par cular they form and establish relaons and iden es between the human and the divine. Rituals in an oecumenically religious understanding are the skills needed to communicate with God, a bridge between the world of phenomena and the transcendental realms beyond. Rituals allow us to evoke and invoke, venerate and worship, praise and banish dei es and demons, destroy

and conquer evil, create and concentrate energies. They deal with desire and devo on, fears and fortunes, prayer and protec on, offering and exorcism. Ritual objects, symbols of Visual Dharma, are all, including ephemeral “minor arts”, like images “spiritual reminders and supports” (ku gung thugs rten), made alive visually in the ritual (bskyed pa).

Together with mantras, mudrās, and the relevant ritual tools, prac oners can, on their way to enlightenment, generate a pure mo va on, increase merit, health and wealth, and ac vate and achieve power and purifica on, lib-

Fig. 15 Vajra on an engraved dharmadhātu maṇḍala surrounded by oil lamps: from a puni ve weapon in ancient India to a powerful Tibetan Buddhist emblem of the indestruc ble truth of the Dharma and its lightning symbolism. Swayambhū stūpa Kathmandu. Unknown date. Photo Daniel Urech (2018).

Fig. 16 Vajra on dharmadhātu maṇḍala at Swayambhū (Svayambhūnātha) stūpa, Kathmandu. Date unknown. Photo Daniel Urech (2018).

Fig. 69 Grain maṇḍala. Gilt copper repoussé and silver appliqué, ht. ca. 35 cm. The mountain-like maṇḍala is combined with a double-storeyed heavenly palace of the Cakrasaṃvara deity, with sun and moon emblems, on a four-stepped square basis conceived as a Mount Meru imago mundi. The four rings are adorned with the Eight Auspicious Emblems, the Seven Jewels of Royal Power, and eight offering goddesses. A er Koller auc on, Zürich 2.6.1989, no. 10.

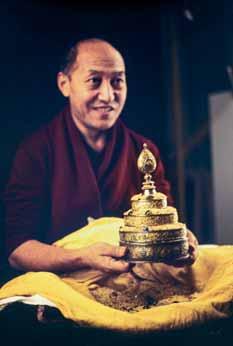

V.1.1 The grain man . d . ala

Also known as a “rice maṇḍala”, this offering-of-the-universe-maṇḍala (dkyil mchod; height ca. 20–35 cm, diameter at the base ca. 15–25 cm) is one of the most common ritual objects in Tibetan Buddhism (fig. 68). The ceremonial prac ce follows that of the Meru maṇḍala (Ch. V.1.2), the tradi on of the 37-maṇḍala-offering liturgy of Chögyal Phagpa (Chos rgyal ‘phags pa, 1235–1280) maintained by all Tibetan schools as an offering to the vajra-master. At the beginning, the surface of the cylindrical “earth-pla orm, golden, pure and powerful”, is cleaned with saffron-scented water and with the “five substances from the

cow” – milk, bu er, yoghurt, dung and urine – to purify the Outer Maṇḍala, and all defilements of the prac oner of the (his) Inner Maṇḍala. Then small piles of grains (tshom-bu), medicinal herbs, corals and semiprecious stones, or just pieces of white stone, are laid upon this base, which is o en engraved with a Mount Meru cosmogram to mark the four con nents and eight subconnents, as well as the central Mount Sumeru with the surrounding “iron walls”. Three (or four) metal rings of progressively smaller diameter are filled with (life-giving!) rice or barley grains building an imago mundi with the cosmic spheres of the mul -stepped “Sumeru, king of the mountains”, as said in a Tibetan text. The rings are adorned with Buddhist symbols, the Seven Jewels of Royal Power, the eight offering goddesses, sun and moon, treasure vase, parasol, the royal banners of the four direc ons, or with inlaid turquoise stones and corals. On top is usually a flaming jewel with a dharmacakra emblem. Other grain maṇḍalas are crowned above a four-storey Meru throne by a divine palace structure dedicated to a specific deity (fig. 69)

The grain-maṇḍala ceremony, which accumulates essen al spiritual merit, is performed by (or with) an authorised monk or by another ini ated prac oner, on behalf of a lay person who commissioned the ritual and who is o en shown presen ng the maṇḍala himself (figs. 70–73). The grain maṇḍala can be offered to the lama when teachings or ini a ons are requested.

Because of non-exis ng criteria and long-las ng formal conven ons, the dating these maṇḍalas on stylis c grounds is in most cases very difficult. And condi on as well the pa na may not allow more than an a ribu on as “old”, “probably old”, or “new”.

Fig. 70 Monk offering a grain maṇḍala. Photo Michael Henss (1982).

Fig. 71 Nuns offering grain maṇḍalas. Dagyab monastery, eastern TAR. Photo Elke Hessel.

Fig. 72 Woman lay prac oner offering a grain maṇḍala, Jokhang, Lhasa, 1996. Photo Michael Henss.

Fig. 73 Offering a grain and a gtor ma maṇḍala. This disc with gtor ma-like par cles corresponds to the lower pla orm of a mul -storeyed grain maṇḍala and serves as an individual object with a polished surface or with an engraved Mount Meru cosmogram, with small “cosmic” grain heaps laid upon as an offering of the World to the divine. During the ritual it serves to visualise the en re offered universe.

Drawing a er Beer 1999, p. 112.

Fig. 76 Mount Meru Cosmos maṇḍala. Gilt copper alloy, cast repoussé, ht. 35 cm, dia. 37.5 cm. China, 3rd quarter 18th century. The central Meru is raising from its surrounding two circular mountain ranges with celes al palaces, and cosmic sun and moon symbols, topped by a stūpa finial. The outer circles of this Indo-Tibetan Buddhist universe consist of the 12 (four plus eight) direc onal palace connents, eight offering goddesses, the Eight Auspicious Emblems, and the Seven Jewels of the Universal Ruler. The base is decorated with Buddhist emblems alterna ng with the masks of fabulous

creatures and pearls garlands. Two rings serve to a ach silk ribbons. Paris, Muséé Guimet, EG 632.

Photo Walter Gross (1998).

Fig. 77 Mount Meru Cosmos maṇḍala. Gilt copper alloy with silver, lapis lazuli and coral inlays, ht. 24 cm, dia. 26 cm. Tibet, early 15th century. This exquisite imago mundi, presented to the 5th Karmapa Dezhin Shegpa (De bzhin dshegs pa, 1384–1415; for the inscrip on on the base, see Annota ons and Inscrip ons), is another version of the portable threedimensional offering maṇḍalas selected for this

chapter. The Eight Auspicious Emblems around the four- ered Meru mountain are placed on the engraved waves of the cosmic ocean and alternate with the lantsha script mantra syllables on the cylindrical base. The four con nents in the cosmic ocean are highlighted by inlaid red corals, blue lapis lazuli, whi sh shell, and yellow amber. For the engraved inscrip on on the upper rim of the base sec on and a painted one on the inner bo om, see Annota ons and Inscrip ons. Bodhimanda Foundaon (V-310).

Fig. 99 An almost completed Kālacakra sand maṇḍala. Drawing begins at the centre and ends with the outermost vajra and fire walls (here s ll missing). Leh, Ladakh.

Fig. 147 Mount Meru torma. Polychromed dough, ht. ca. 150 cm. Ya chen sgar monastery (see fig. 144), early 21st century. In iconography and form, this extraordinary sacrificial offering “torma” represents the Sumeru World Mountain universe with the mulered celes al spheres and divine palace on top, raising form the cosmic ocean and its four con nents and seven golden mountain ranges. Among the decora onal details, par ally of modern iconogra-

phies, one can recognise dancing ḍākini-like offering goddesses, the four guardians, birds and other animals, palm trees, clouds, four dragons and a vase with half-vajra finial at the palace roof. Photo Rolf Koch (2018). See also fig. 599.

Fig. 147a Detail of fig. 147: The Mount Meru cosmos ocean with the outer fire-wall of a maṇḍala enclosure. Photo Rolf Koch (2018). See also fig. 599.

Fig. 148 Mount Meru maṇḍala torma. Gilt metal repoussé, ht. ca. 180 cm. Ya chen sgar monastery (see fig. 144). The four ers of this unusual monumental “torma” are filled with “grains”, here replaced by “precious stones”, in fact coloured glass par cles and other materials. The four rings are adorned with offering goddesses, the Eight Auspicious Emblems, uniden fied figures, and scrolling floral ornaments, the celes al palace walls on top with kauri shell and crystal hangings. Photo Rolf Koch (2018).