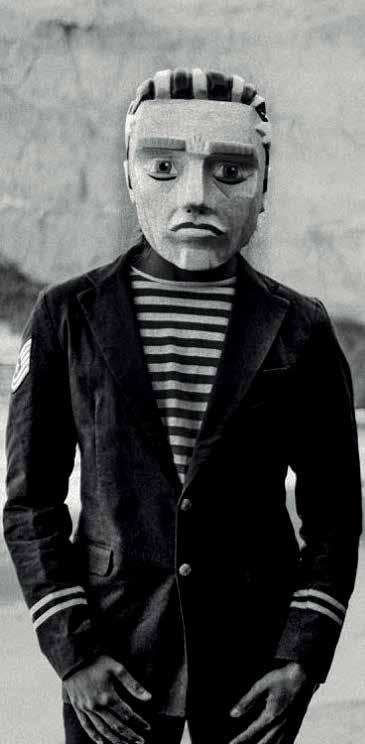

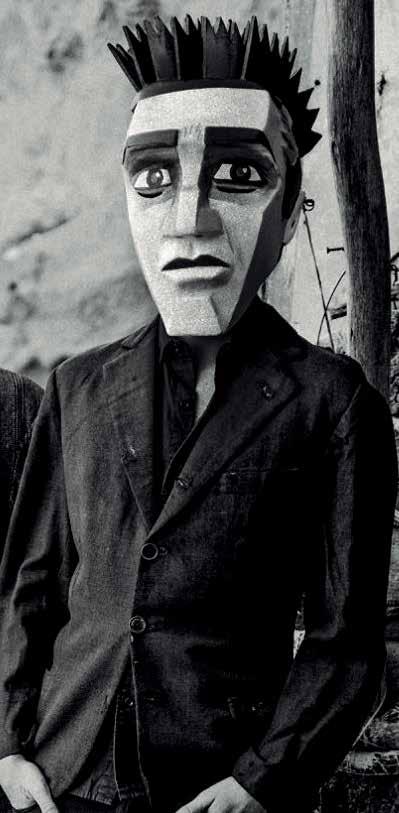

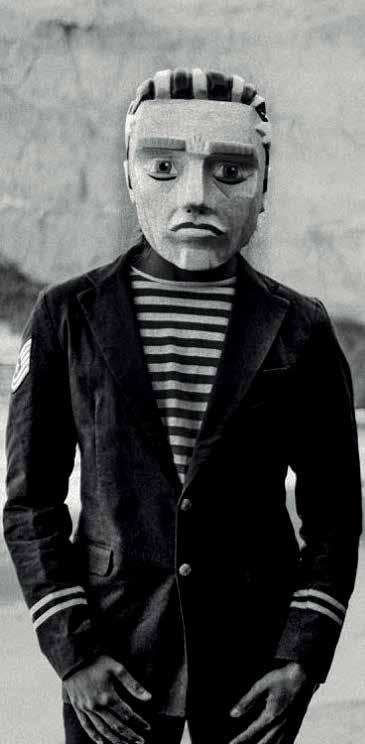

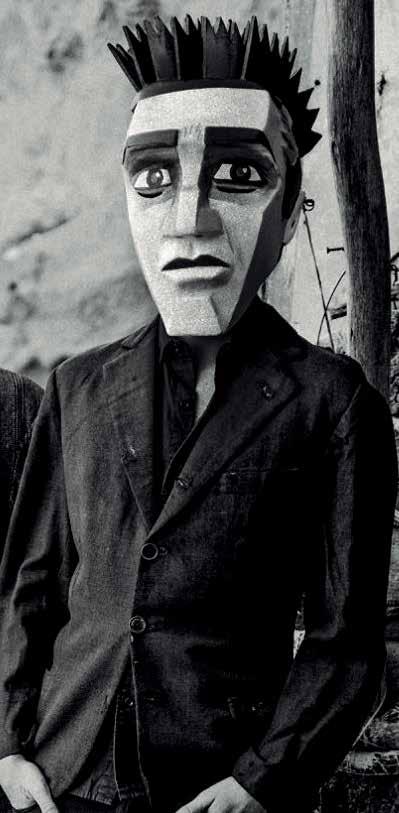

WITH MORE THAN FOUR DECADES OF HISTORY, THE ARGENTINE BAND IS AMAZED THAT NEW GENERATIONS CONTINUE TO FOLLOW IN THEIR FOOTSTEPS

Migration has been a constant throughout human history, shaping civilizations and redefining the boundaries of nations. Today, more than 300 million people live outside their country of birth—the highest number ever recorded.

BY: EUNICE

Yet the current landscape is particularly complex. Restrictive border policies in the United States, heightened enforcement operations, and shrinking access to asylum have reshaped mobility in the Americas. Mexico, once viewed primarily as a transit country, has now become a destination. Refugee claims are soaring, thousands remain stranded without clear legal pathways, and communities face the challenge—and opportunity—of incorporating migrants as neighbors, workers, and contributors. It is against this backdrop that Migration: Wellbeing and Labor Inclusion, edited by Agenda Migrante and the Comisión de Derechos Humanos de la CDMX, emerges as a vital contribution. Far from being just another policy report, this book is a collective and multidisciplinary reflection that brings together entrepreneurs, legislators, civil society organizations, international agencies, academics, migrants themselves, and public officials. The result is not merely a diagnosis, but a roadmap for transforming migration from a perceived burden into a source of shared prosperity.

The book begins with a powerful reminder by Sergio Salomón Céspedes Peregrina, Commissioner of Mexico’s National Migration Institute: migration is not a crime, nor an error to be corrected, but a deeply human phenomenon that has accompanied humanity for millennia . This framing sets the tone for the entire work. Migration must be approached through the lens of dignity and justice, not containment and suspicion. A central thread running through the volume is the idea of productive inclusion. Mexico currently faces 1.6 million job vacancies, according to COPARMEX. At the same time, the Business Coordinating Council, through the “México te Abraza” initiative, has mobilized over 380 companies to offer more than 70,000 positions for returning migrants. As several contributors argue, linking labor demand with migrant talent is not only possible but urgent. However, this requires advancing regularization, facilitating access to financial services such as bank accounts, and ensuring that inte-

gration into the formal labor market occurs under conditions of legality, security, and non-discrimination.

The richness of the book lies in its diversity of voices. Nashieli Ramírez highlights the particular vulnerabilities of women in mobility, who demand gender-sensitive responses. The plight of migrant children— bearing a double vulnerability—receives special attention, with Gloria Ciria Valdez Gardea stressing the educational dimension and the need for institutional support for their schooling. Giovanni Lepri, representing UNHCR in Mexico, reframes refugee integration not as charity but as smart investment. Meanwhile, business leader Francisco Cervantes argues that accelerating legal migration is essential to building a future of shared growth. Legislators also weigh in with urgency. Amalia García outlines the elements of a paradigm shift away from a control-first approach; Karina Ruiz underscores the importance of legislating with a migrant-centered vision; and Marcela Guerra connects migration directly to the Sustainable Development Goals, reminding us that the wellbeing of migrants is an indicator of national progress. Scholars like Javier Urbano Reyes advocate for a renewed migration policy in line with institutional reform, while Jorge Lera Mejía and María Bárbara Lera Castellanos stress that opening legal pathways is key to reducing risks and exploitation. The book also broadens the lens beyond policy and economics. Jorge Ulises Corona explores the delicate balance between national security and mobility, noting that protecting rights strengthens rather than weakens security. Abel Gómez Gutiérrez and Blanca Yadira Salazar examine Mexico’s dual identity as both a country of transit and destination. Literary contributions by Hugo Alfredo Hinojosa and Carlos Mora Álvarez remind us that migration is also a story of exodus, longing, and identity. These narrative pieces ensure that the debate does not lose sight of the human experience behind the numbers.

Taken together, these perspectives construct a vision of migration as an opportunity for social resilience, economic dynamism, and cultural renewal. The proposals are concrete: streamline regularization processes for those already in Mexico, expand financial inclusion, build multi-level governance that engages local and federal actors, and foster collaboration with the private sector to match vacancies with skills. Most importantly, the book insists on a guiding principle: dignity is not negotiable.

At a time when public discourse is polarized, and migration is often reduced to numbers or security threats, Migration: Wellbeing and Labor Inclusion offers a refreshing, human-centered narrative. It is both a critique of outdated containment strategies and a practical guide to designing policies rooted in justice, responsibility, and opportunity. The message is clear: migrants are already part of our communities. The choice is whether to exclude them—at great social and economic cost—or to embrace their contributions and build stronger, more prosperous societies together. This book ultimately calls for courage. Courage to move beyond fear-based narratives, to recognize migration as a historic constant, and to legislate, govern, and innovate with humanity at the core. As the essays collectively demonstrate, embracing migration is not only a moral imperative but also an intelligent strategy for the future of Mexico and the region.

THE MADE IN MEXICO LABEL HAS BECOME A SYMBOL OF IDENTITY, INNOVATION, AND QUALITY FOR THE COUNTRY’S TEXTILE INDUSTRY. STRENGTHENED BY GOVERNMENT SUPPORT AND GROWING U.S. DEMAND, IT NOW BOOSTS COMPETITIVENESS, CULTURAL VALUE, AND GLOBAL RECOGNITION FOR MEXICAN MANUFACTURING.

BY:

The Made in Mexico label is more than just a modern mark — it’s a symbol of identity, innovation, and dedication to quality that Mexico’s apparel industry has steadily developed over the years. With the support and active involvement of the current government, Made in Mexico has become a trusted indicator for consumers seeking reliability and excellence in domestic products.

Since its inception, the brand aimed to unite companies that shared a common vision, meeting high standards of quality, innovation, and respect for design and manufacturing processes.

For the textile industry, this presents a renewed opportunity to boost domestic production, improve manufacturing, invest in technology, and open markets that once seemed unreachable. In this context, the Mexican Association of Apparel Producers has collaborated closely with the government to integrate the textile and garment ecosystem— focusing on everything from business digitalization to enhanced design and quality control, which are essential for competing in demanding markets like the United States.

The relationship between Mexico and the United States is, without question, strategic and essential for the textile industry. In 2025, Mexico remains the top exporter of apparel to the U.S. and the second-largest overall supplier, accounting for about 13% of the U.S. clothing market. This means that one in every five garments sold in the United States is made in Mexico, reflecting the confidence that both American brands and consumers have in Mexican production.

Geographic proximity and quick response times, combined with competitive costs, have made Mexico a key player amid Asian competition and the growing demand for fast fashion.

However, this activity is not limited to

large-scale manufacturing. The current Mexican label has also increased visibility and appreciation for regional and artisanal products—such as huipiles, ancestral embroidery, and traditional textiles like tenangos. These creations, which showcase Mexico’s rich cultural identity, have found a niche in international markets that value authenticity, creativity, and the story behind each piece. In short: Mexico is in fashion.

In U.S. cities with large Mexican communities, these products have become popular for their design, comfort, and cultural significance, helping to promote a positive image of Mexican craftsmanship and expand into new markets beyond traditional consumers. Mexico’s textile industry currently accounts for about 2% of the national GDP and employs thousands of people across the country, from large factories to small artisanal workshops. Digitalization, process innovation, and the pursuit of global standards have been vital to maintaining competitiveness.

“Made in Mexico” has been a driving force for these changes, encouraging companies to raise their standards and adopt strategies that help them not only stay afloat but also grow in an increasingly competitive global market dominated by China.

Another important aspect of the Made in Mexico brand is its ability to foster trust among international consumers— especially in the United States. A few years ago, there was a perception that products manufactured in the U.S. were of higher quality. Today, the reality is that Mexican manufacturing meets the strictest standards in design, logistics, and process control. Mexican companies are now ready to respond quickly, flexibly, and creatively to the needs of binational markets, using both their geographical proximity and a deep understanding of the North American consumer.

From the perspective of the Mexican Association of Apparel Producers, Made in Mexico signifies a collective commitment: from producers, to ensure quality and authenticity; from the government, to promote standards and expand trade opportunities; and from consumers, to appreciate national products. The brand has grown beyond just a commercial symbol—it’s become a cultural and economic benchmark that showcases Mexico’s textile industry competitiveness in a binational context, strengthening connections with the United States and shaping the future of Mexican manufacturing. Looking forward, Mexico’s textile industry has a historic opportunity: to boost its share of the U.S. market, diversify its products, and build an offering that combines technology, design, and tradition.

The United States is, without a doubt, a key partner in this journey—helping ensure that Mexican production not only competes but also stands out for its quality, innovation, and cultural significance. The Mexican textile industry has

BY: ALEJANDRA ICELA MARTÍNEZ RODRÍGUEZ ARTWORK: ALEJANDRO OYERVIDES

Their creator, Swedish chemist, engineer, and inventor Alfred Nobel (1833–1896), amassed a vast fortune thanks to 355 inventions, the most famous being dynamite. Although his invention had civil uses, many of his developments were related to weaponry, which profoundly impacted his legacy.

A significant event in 1888 altered his fortune’s trajectory. After his brother Ludvig passed away, a French newspaper mistakenly published Alfred’s obituary, titled “The merchant of death is dead” (“Le marchand de la mort est mort”). Deeply affected by this portrayal, Nobel decided to amend his will on November 27, 1895. In his final testament, he allocated most of his wealth to establish a series of prizes for those who confer “the greatest benefit on humankind.” These awards, first given in 1901, became a legacy dedicated to advancing progress and peace.

The Prize in Economic Sciences was not created by Nobel himself. It was established in 1968 by the Bank of Sweden (Sveriges Riksbank) in his memory. Officially called “The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel,” it is also managed by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Mexicans not only seek to improve their own conditions and those of their families, but also, through their daily work, contribute to the economy, society, and culture of the countries that host them, wherever they may be.

fellow Mexicans overseas. When they’re far from home, that representation, that consulate, that embassy can be the bond that keeps them connected to Mexico.

BY: GONZALO LIRA ARTWORK: ALEJANDRO OYERVIDES

R.M. It’s a pleasure to welcome you here at the casa de México, the Consular Section of the Embassy.

G.L. I like hearing “casa de México,” because I think it’s very important to have a place where people can arrive and feel at home. I believe the work you do is related to that: creating a space where people can come and feel confident, comfortable, embraced.

R.M. It’s very important that they have the opportunity to reconnect with their roots, and consular work is part of that— whether it’s helping their children obtain dual nationality, process a passport, or get their voter ID card. But it’s also about community: networks of Mexican communities and university alumni, participation in activities like the entrepreneurship program for Mexican women abroad, or the altar contest coming up for Day of the Dead.

G.L. This shows me the wide range of things you do for the Mexican community in the United States. We were talking about how you came into this position, so that you can tell people where this need to serve our country and our people comes from.

R.M. It’s a vocation for service, and it comes from my family. I had the honor and privilege of being the son of a member of the Mexican Foreign Service, who instilled in me this tradition, pride, and honor of serving our people abroad—where you can truly make a difference and care for our

*Rodrigo Mendivil Ocampo is the Head of the Consular Section of the Embassy of Mexico in the United States.

G.L. We’re talking about those little details that need to be addressed—from the smallest ones, like finding your favorite dish away from home, to having a place where you know you’ll be supported in any circumstance that may be complex in a foreign country. Has it become more complicated to serve our nation these days? What challenges have you faced since taking this position?

R.M. I think we’ve always faced complexities that come and go, but Mexico has always had a very strong consular tradition. We have the largest consular network that one country has in another. That makes us an example for many other nations in how to implement consular work. We continue to serve people closely. We have very clear instructions from our president, Claudia Sheinbaum, and we are fulfilling them—getting closer to people, trying to provide every possible service, understanding their needs. For example, we’ve seen an increase in parents wanting to register their children born here in the United States to obtain dual nationality, and those are some of the services that have grown. These are complex relationships, no doubt, but they keep moving forward, and Mexico has always advanced in caring for its people.

G.L. A moment ago you mentioned the services you provide, such as free healthcare, and you just spoke about dual nationality, which has been increasing. What were the areas you realized needed to be strengthened when you arrived at this position? What was the first thing you said, “I need to address this, because it’s been overlooked—or maybe there’s an opportunity to improve it”?

R.M. I had a great advantage—my predecessor in this position, now Consul General of Mexico in Atlanta, is an excellent consul and leader. So, I wouldn’t say there was any neglected area.

The DC-VA-MDWV metro area has ≈ 1.1 million Hispanics, about 17.6 % of its 6.26 million people.

In Maryland ~744,000 people are Hispanic, making up about 12.1 % of the state population in 2023.

West Virginia’s Hispanic population is small: approx 36,100, about 2.02 % of the state in 2023.

In the DC-VA-MDWV region, 23.7 % of residents are foreign-born (~1.49 million people).

Each person has their own points of interest and way of approaching things, but I feel there wasn’t any neglected area. What we’re doing is building on the excellent work done by Consul Laveaga, whose success earned him the post of Consul General in Atlanta. Our goal is to get even closer to the people and see how we can serve them better. The Health Window project is led by the Institute for Mexicans Abroad (IME). It helps us provide services, especially for people who come here to the Consular Section for any procedure. They have access to a window where they can receive some medical services for free, as well as guidance if they need it, on any health-related issue. We also have other community outreach programs, like the Financial Advisory Window, where two of our partners come to give talks to people waiting for their services about topics such as tax filing in this country.We have an Educational Guidance Window as well; we work with IME on the IME Scholarships initiative. We just completed another round of this program and awarded funds to two educational institutions to benefit Mexican students within our jurisdiction. There are many ways to connect with and serve people.

G.L. You also spoke about the altars, and it seems that throughout your career you have paid a lot of attention to cultural matters. I think cultural work gives us a lot of identity, and i’d like you to tell me how you also attend to that side, because it’s one of the most essential parts.

R.M. As a consular section we have cultural programs carried out with the IME, such as this altar challenge, in which not only do the missions compete to create the best Day of the Dead altar, but community organizations also take part in their creation. We also have a cultural institute that handles all cultural dissemination. I have organized cultural promotion activities in my previous roles, and it’s impressive how Mexican culture has reached every corner of the world—not only the example it sets and the admiration it receives from citizens of other countries, but the need for Mexican migrants or second- or third-generation Mexicans to reconnect with their roots. There are other programs of interest. For example, with the IME we have the Dreamers Forum program, to reconnect these second and third generations and other people of Mexican origin with their roots; they have activities in Mexico and go there to reconnect and truly see what our country is like. For some, it is their first time doing so.

G.L. Earlier you told us a fact that I find very interesting: in this district, Mexican identity is not the principal Latino identity, and in some way that makes it more complex to build a united community. What are the challenges to amalgamate a Mexican community in this particular district?

R.M. I think it’s very important to reach out to the community to let them know all the services we provide, but also to generate an interest in joining with other Mexicans, in getting to know one another, in creating support networks.

Because when a Mexican leaves their country in search of better opportunities, in search of work, they sometimes leave their entire family behind, and being able to reconnect with Mexicans abroad is one of the ways to maintain that connection to Mexico. Here we have approximately 320,000 Mexicans in the area we cover; we are not the majority Latino group in this region—there are more Guatemalans and Salvadorans here than Mexicans. That means you find Mexicans in these different states who are looking for that connection, who are looking for those networks. So there are different ways to

approach it.

You can approach it from the professional area through university networks—of which there are several—but there are other networks that also form to keep contact among themselves; these are social in origin, started to bring a group of Mexicans together to, for example, watch the national team’s matches, or to support a Mexican cause after a disaster. It is very common that the Mexican community abroad responds positively to those needs in our country. So we have to reach them. We do this by providing all services here at headquarters, but we also operate mobile civil-registry consulates to meet demand for registering children born abroad so they can acquire dual nationality. We also have “consulates on wheels” in locations somewhat further from the office to try to bring consular services closer—especially the main ones: applying for a passport, obtaining a consular ID card (matrícula consular), obtaining a voter ID card—in a place that’s a little closer for those people.

G.L. You mentioned another interesting point: many Mexicans here work in academia and the professions. I think that also completely changes many of the stereotypes about the Mexican community in the United States.

R.M. We have a very heterogeneous community. We have workers in all industries: services, restaurants, construction; in every sector. Perhaps because of the specific characteristics of Washington we have a higher number of professionals and academics than in other parts of the United States. But all of them, through their work, demonstrate this vision that Mexicans go and, through their labor, not only seek to improve their own conditions and those of their families, but also, through their daily work, contribute to the economy, society, and culture of the countries that host them, wherever they may be.

G.L. What do you guys think you can strengthen, and where are the policies headed that, together with President Claudia Sheinbaum, you are trying to implement in this specific area but also in coordination with the rest of the consulates?

R.M. I think the main thing has been that need to bring the consulate closer to the people. We need people to feel attended to, and to be able to meet their needs, and that implies a lot of fieldwork. Being Consul of Mexico is a great pride, but it is not an office job. You have to go out; you have to see people. I’ve been in this assignment for a short time, which has entailed many administrative processes that had to complete before could direct my attention to other topics. But my purpose for the future is to begin to have all the outreach to communities a little further from headquarters: to go out into the field, to see people, to meet with authorities, which is also one of our most important jobs—having dialogue with the governments we deal with, local and state governments. Those are meetings that allow us to have a diagnosis of our community in the states we cover, because we see it both from our communities and from our community leaders, with whom I also hold meetings, but also from the perspective of local governments: what needs have they identified and how we can have closer dialogue. So what is my next objective for the coming months? To get as close as possible to the people.

I try to do that even when I’m here at headquarters. I go out every day to see how the public service area is doing, to introduce myself to them, so they know that if any situation arises in their service, they will always have my door open to come to me directly and I make sure they receive the best possible attention.

OVER THE YEARS, MEXICAN AND MEXICANAMERICAN PLAYERS HAVE LEFT AN INDELIBLE MARK ON THE NFL, SHOWING THAT TALENT KNOWS NO BORDERS.

BY:

Their participation has gone beyond statistics and trophies—it’s about representation, resilience, and pride. Each player carries a story of effort, sacrifice, and cultural identity that connects two nations through the power of sport. For millions of fans in Mexico, their presence on the field transforms the league into something more than just a game; it becomes a reflection of shared roots and aspirations. These athletes have not only raised the profile of Latino talent in professional football but have also paved the way for future generations. Their stories prove that success in the NFL isn’t limited by geography or background— it’s shaped by determination, discipline, and the courage to dream beyond borders. Whether through historic achievements, leadership, or inspiring journeys, they remind us that Mexico’s influence on the game continues to grow stronger with every season.

l Born in Monterrey, Isaac Alarcón’s journey from college football in Mexico to the NFL embodies persistence and global ambition. After joining the Dallas Cowboys through the International Pathway Program, he now trains with the San Francisco 49ers, one step away from debuting in a regular-season game. His path reflects how Mexican athletes are steadily gaining ground in the most competitive football league in the world.

l A rising star on the Los Angeles Rams’ offensive line, Steve Avila—born to a Mexican father and African-American mother—has quickly proven his value through consistency and adaptability. His ability to play multiple positions and his relentless work ethic make him a cornerstone of the Rams’ offense. Still young, he’s become a symbol of quiet strength and reliability in one of football’s toughest positions.

elite athleticism with leadership and discipline, earning multiple All-Pro selections and becoming the league’s highest-paid linebacker. Though a recent injury paused his season, his legacy as a leader and role model for Latino players remains intact.

l Carolina Panthers quarterback Bryce Young, whose maternal grandfather was born in Mexico, proudly embraces his heritage while shaping his own history in the NFL. The 2021 Heisman Trophy winner is now leading his team toward playoff contention, showcasing calm precision and maturity beyond his years. He represents a new generation of biracial and bicultural athletes redefining what it means to be American— and Mexican—in sports.

l Known as the “Punt God,” Matt Araiza has turned a powerful leg into his signature. With family roots in Mexicali, he overcame early career setbacks to make a successful debut with the Kansas City Chiefs, even reaching the Super Bowl. His resilience and focus earned him a Pro Bowl alternate spot in 2025, marking the start of what promises to be a long and inspiring career for one of the NFL’s most talented special teams players.

Following their performance at Mexico City’s Vive Latino festival, the group will tour cities like Chicago, Miami, and Brooklyn. They’re not ruling out the possibility of releasing a new studio album.

“In the near future, though I can’t pinpoint the exact time, we’ll reunite in a studio to record, as that’s our shared desire, our chosen path, and our ability to accomplish,” said founding member Flavio Cianciarulo, also known as Sr. Flavio. Saxophonist Sergio Rotman concurred, stating, “We’ve both maintained a high level of creative activity, so there’s no doubt that we’ll eventually come together to create a new record.”

After over four decades of

They’ve collaborated with various Argentine and international artists and have received awards and nominations from MTV Latinoamérica, Premios Gardel, Fundación Konex, and the Grammys.

a remarkable partnership, the band’s enduring longevity continues to astound them. Flavio expressed gratitude, saying, “We’re in our sixties, yet we still rock with unwavering intensity and energy—it’s a blessing. When we were in our twenties, Vicentico once asked me, ‘What will we do when we’re 45?’ Back then, we believed our journey would end there. Now, at 61 and 62, we continue to jump and rock with passion. It’s incredible that people still recognize our contributions and place us in such a high regard.”

Los Fabulosos Cadillacs’ enduring appeal across gen -

In June 2023, they performed before 300,000 people at Mexico City’s Zócalo.

The legendary Argentine band Los Fabulosos Cadillacs is gearing up for a new series of shows across the United States and Mexico, keeping the energy of their music alive after four decades

Their upcoming performance at Mexico City’s GNP Stadium is scheduled for November 22, 2024.

erations remains an enigma, a source of both fascination and wonder. Flavio expresses amazement at the sight of new generations connecting with their music at their shows, acknowledging that while they could analyze the reasons behind this connection, they prefer to leave it in the realm of surprise and gratitude. Rotman further explains that their music resonates with different generations because they come from a time when musicians were expected to master a wide range of styles. This diverse musical background makes them impossible to

albums, including La salvación de Solo y Juan (2016).

categorize, contributing to their universal appeal. The band holds a special place in their hearts for the memory of their record-breaking concert in Mexico City’s Zócalo in 2023. Over 300,000 fans gathered to witness the performance. Flavio expressed a sense of privilege and admiration, stating, “The Zócalo is a chapter apart. Knowing the rich history and significance of that stage, it was an honor to perform there. My deepest respect and admiration go out to the Mexican people.” When asked about their legacy, Flavio reflected on the role of music as a form of social commentary. “There are still many artists who convey powerful messages,” Flavio said. “We shouldn ’t limit ourselves to mainstream music. The underground scene is full of raw and beautiful music that deserves to be heard.”

The story of Harumi López, a CETYS student in Ensenada, illustrates how a passion for science and programming can open incredible doors—even up to the sky. From a TikTok video to working with NASA’s Lucy mission, her journey combines discipline and creativity.

BY: OSO OSEGUERA

Curiosity and a passion for scientific research have guided Harumi López, a Software Engineering student at CETYS, Ensenada University International Campus, along an unexpected path that now brings her closer to her greatest dream: becoming an astronaut. Her story combines academic discipline, technological ingenuity, and the ability to cross boundaries between science, technology, and art— elements that have opened doors to unique experiences.

From a young age, Harumi knew programming was an endless canvas. She participated in the Mexican Informatics Olympiad in middle school, where she started solving problems with logic and code. Years later, she realized this was the foundation of her passion: “I understood that Software Engineering allows me to work in an interdisciplinary way,” she says. That vision of bringing together different fields of knowledge has been a core part of her growth. At CETYS, she received not only academic training but also chances to meet researchers, scientists, and science communicators. “Thanks to meeting these people, I’ve learned so much from them. Some have even supported me in several of my projects,” she says, recognizing that these collaborative networks are essential for thriving in the scientific community.

THE TIKTOK THAT CHANGED HER PATH

In December 2023, Harumi decided to record a video to apply for a space camp led by Katya Echazarreta, the first Mexican woman to travel to outer space as part of the NS-21 mission. In the short clip, the young woman from Ensenada shared her scientific interests, and soon the video surpassed 100,000 views on TikTok.

Although she wasn’t chosen for the camp, the video’s impact led to an unexpected opportunity: an invitation to join NASA’s Lucy mission’s astronomical observation campaign. The challenge was significant—capturing from San Felipe, Baja California, the exact moment when Polymele, one of Jupiter’s Trojan asteroids, passed in front of a star—a brief event that demands complete precision.

“I realized that the more you practice and step out of your comfort zone, the easier things get,” she recalls. The data collection was so successful that it will be part of a future scientific paper, directly contributing to the mission.

Harumi’s education extends beyond engineering. In high school, she played guitar, and in college, she participated in the university’s theater group. Both activities, she says, have been crucial in developing key

skills like communication, leadership, improvisation, and teamwork.

“Art has taught me to solve challenges in real time. That ability to improvise is the same one apply in my engineering career,” she explains. This combination of interests enables her to approach scientific problems from different perspectives, with the mental flexibility that space exploration requires.

ASTROCLUB: SCIENCE FROM THE UNIVERSITY

Motivated by her experience with the Lucy mission and her growing interest in astronomy, Harumi founded the Astroclub at CETYS. It’s a space where students from different fields come together for observation nights, outreach projects, and research activities. In just a few months, the club organized visits to the National Astronomical Observatory in San Pedro Mártir, collaborated on Noche de las Estrellas—an event that brings together more than 8,000 volunteers across Mexico— and participated in the NASA Space Apps Hackathon, a global innovation marathon focused on developing data-based solutions for space exploration. The club has also formed partnerships with programs like CANACINTRA’s ExploraSTEM, expanding scientific outreach to more youth in Ensenada and across Baja California. Harumi’s dedication has been recognized. She has won the Coder Bloom’s Monthly Programming Contest twice, a competition with over 100 participants from Latin America. In 2024, she was honored at the NASA International Space Apps Challenge for creating a web application that tracks near-Earth objects. That same year, she served as an observer during the Polymele astronomical campaign in Baja California, organized by the UNAM Institute of Astronomy and the Southwest Research Institute to support the Lucy mission. She also received a gold medal at the Baja California Informatics Olympiad and graduated with the highest GPA in her CETYS class.

BEYOND BORDERS

Today, Harumi combines programming, data analysis, and machine learning in research projects that explore coping strategies among young people. She also actively collaborates with Future Bloom, an organization that encourages Latin American women to participate in technology. Her vision for the future is clear: to stay at the crossroads of software and space science while continuing to improve her training to achieve her dream of becoming an astronaut. For her, the path doesn’t have to be straight. Being open to interdisciplinarity helps you develop many skills—a flexible mindset that enables you to connect ideas that might not seem obvious at first,” she says.

Harumi López’s dream of becoming an astronaut is still underway, but her story already inspires hundreds of young people in Mexico. At just 20 years old, she has shown that a passion for science, combined with technological discipline and art, can open horizons as wide as the universe itself.

“The most important thing is to trust yourself and surround yourself with people who believe in your dreams,” she says. And with every step she takes, Harumi confirms that her journey—though not linear—is steadily taking her closer to the stars.